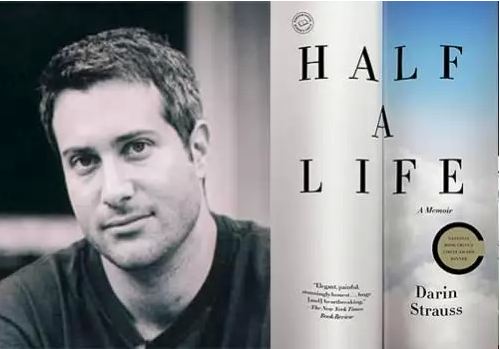

Darin Strauss is an American writer who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. He is the author of three novels and one book-length memoir. Strauss is married to the journalist Susannah Meadows, and together, they are the proud (and busy) parents of twin, four-year-old boys.

Strauss’ 2010 memoir, Half a Life, won the 2011 National Book Critics Award and was excerpted in GQ and NPR’s This American Life. Half a Life chronicles the aftermath of a motor vehicle accident in which Strauss was the driver. His car struck and killed a young girl whose bicycle swerved into the road. Cleared of any wrong-doing in the accident, Strauss writes about the effect of this traumatic event which haunted him for twenty years. Hailed as a “masterpiece” and as a “memoir in its finest form,” the book has garnered critical acclaim and was named ‘Best Book of the Year’ by NPR, Amazon.com and others.

Chang and Eng, Strauss’ first book, was published in 2000. The novel, which tells a fictional story of the famous real-life conjoined twins, Chang and Eng Bunker, met with widespread critical acclaim. Set in Siam and antebellum North Carolina, Chang and Eng bravely explores the concept of self and other through the lives of the eponymous Siamese Twins, who came to the United States, became farmers, husbands and fathers. Strauss’ unflinching exploration of the twins’ story, told from the point of view of Eng, won many major literary awards and is currently being optioned for a movie. After Stauss’ second novel, The Real McCoy, he won a Guggenheim Fellowship. His third novel, More Than It Hurts You, was published by PenguinPutnam in 2008.

We speak over the phone. I reach him early in the morning and he asks if I can call him back. He is getting his boys ready for school. We talk amidst the street noise of rush hour New York, as Strauss goes for his morning walk through Brooklyn. At one point, I reluctantly offer up that I’m a Patriots fan. His New York Giants have recently defeated my favorite team for the second time in a Super Bowl. He is gracious in victory. I tell him that my son cried for fifteen minutes after the game and he says that I’m the second person who has mentioned this phenomenon. Being a parent changes the way we enjoy sports, in addition to how we live our lives. He is generous and quick with his responses. Once again, I’m reminded that even the most successful writers, and Strauss is clearly one of these, retain a sense of wonder and humility at the practice.

Richard Farrell (RF): Is there a spiritual tradition from which your write? How do ideas of spirituality and religion affect how you approach your work?

Darin Strauss (DS): I don’t know about that one. I’m not a fully LAPSED Jew. I do believe. But I don’t go to temple and I don’t speak Hebrew. I’m a very secular person. I suppose the closest I come to a true spiritual tradition might be the literary tradition. For me, there’s something almost liturgically intense in the best writing. Someone like Tolstoy or Bellow. People like that created texts that have an important gravity; they pull on my brain the way the Talmud would pull on another Jewish person’s brain. I think Tolstoy is the best writer we have ever had. I’m sure he wouldn’t be impressed by someone like me saying that – big whoop, right? — but for me, there is something spiritual about being engaged with reading a work of literature like that.

RF: You wrote three novels before Half a Life was published. Beyond the thematic material, can you talk about the process of writing non-fiction compared to writing fiction?

DS: I find in memoir it is harder to make a coherent whole—I mean an artful structure. The great and popular writer David Lipsky helped me significantly in structuring the book. I was lost with it. He said do this and change that–he actually did some real stuff in there for me. The material in the memoir was so close to me personally I couldn’t see it. Ask any sea captain: When you are too close to something, it’s hard to get perspective.

In fiction writing, the difficult stuff is testing to see if what you’re writing is believable. For the memoir, that problem vanishes: it’s the truth you’re working with. I just had to figure out how to make the structure of it work.

A lot of people have asked me why I didn’t just write a novel about what had happened? I chose to do it as CNF because for me, fiction has a kind of narrative playfulness about it. There has to be fun involved in fiction, even if its fun played out in a serious way. There’s a gamesmanship to it. All fiction writing involves intellectual play, in other words. I didn’t feel like I could do that with the memoir. It would have been disrespectful to the memory of the girl who died. The thematic and textual art-making in fiction would’ve disrespected the actual events of an actual life.

RF: You’ve talked about being sensitive to critics and reviewers. Does that, for lack of a better word, anxiety, ever work its way into your writing? I suppose what I’m asking is, does your sensitivity make you defensive at all?

DS: I can wall off certain demons. I do read reviews. I mean if I’m going to be reviewed in the New York Times or the Washington Post, I’m not strong enough not to read the review. But it does affect you. You become sensitive to the slights. But I’m good at walling that part of myself off when I write. The reviews don’t get in there, into that place where I’m writing.

Maybe if there was a bad review that seemed to understand my writing—that got at the very specific flaws I know are there—that would bother me more. I think most writers—most of us non-genius writers –know deep down what our flaws are. But I haven’t had a bad review that focused on what I feel are the secret, weak parts of my work. I haven’t had a critic that made a point that could make me think to be a better writer.

RF: I want to ask you about writing sex scenes. I’m thinking specifically about the scene in Chang and Eng where the conjoined twins have sex for the first time to their new brides. I found this scene (really two back to back scenes) highly erotic (and well written). Rather than being turned off by the oddness of the situation, I found myself identifying with Eng in a very personal way. Besides accepting a compliment to your writing, can you talk about how you approach sex scenes, or scenes of physical intimacy in your writing?

DS: (Laughs and points out my inadvertent pun on ‘back to back’) I knew that was going to be one of the main questions of the book. How were they able to father 21 children? I knew I had to address how they had sex and that it was going to be essential.

Sex scenes always create a problem. And they have to serve the story. You can’t just stop in the middle of a scene and forget everything—just for a little textual thrill. I mean, it’s best not to be merely prurient about it. Here’s an analog to sex-scene writing. I think of a scene where a character walks into an ice cream shop. You have describe things that matter, but you can’t stop the forward motion of your story just to have a six-page description of the sprinkles and the cone. How the sprinkles and the cone move your story along, how they affect your particular characters in ways that are particular to them—that’s a good scene.

For that sex part in Chang & Eng, I focused on the conflict between those two men and the trouble with having your brother constantly with you. There was no intimacy, nothing was ever private. But I also wanted to conceive the sex scene as something that could get at what was special about this thematic material and this plot. So I made Eng in love with his sister-in-law. But he could never tell her or touch her because the woman’s husband—his brother—was always with her. The sex was an extension—or an elucidation—of the problem.

RF: Do you have (or did you) other writers you modeled yourself after? Who and how did you escape that influence? How did you get out of its way.

DS: I’m always picking up new influences. You certainly don’t stop being influenced. Zadie Smith said something like, ‘A writer should approach the library the way an eater approaches the buffet table.’ Like: I’ll take from this, from that, and also from that. That cobbled-together meal ends up—if you have enough various dishes in there, in various quantities—being something unique to you.

The writers influential to me include Tolstoy, Nabokov, Lorrie Moore, Martin Amis, John Cheever, Isaac Babel, V.S. Pritchett. Pritchett isn’t read much anymore but he was a great writer and a critic who kept writing late into his eighties. David Foster Wallace too, and Roth. A dash of Updike, a touch of Chekhov.

So I’m always reading and being influenced. I don’t think that ever stops.

RF: How important is voice to you in writing?

DS: It’s important. If there’s a morality in writing, it’s in the voice or the style. Nabokov made that point, and lived it, too. I try to see what other writers do, and to figure out how to do it myself.

Nabokov was great at compressing metaphors. David Lipsky teaches his students to look at what Nabokov does with metaphors and try to find ways to use that. Or David Foster Wallace, and how well he uses incredible modifiers to jazz up the prose.

But, to get less craft-lessony for a second. When I read Tolstoy, it’s a chance to take a ride in the brain of a genius for a few weeks. That’s the part that movies and TV can’t get at, because you are always watching the pictures with your own eyes, and having your own observations. Which I’m guessing are limited than Tolstoy’s. But if you read Tolstoy, you really are existing in his brain, getting the full strength of his thoughts. I think of it like brain vitamins.

RF: My last interview was with Anthony Doerr. He also has twin boys. I hope it’s not something in the well water. How has being a parent effected your writing?

DS: (Laughs) It’s made me have less time to write! My third book was about someone harming a child. But now when I get to a place in a book, maybe it’s harder to go to the cruel places. But I don’t think it’s affected my writing in a negative way, beyond having less time.

RF: In Half a Life you say, “Things don’t go away. They become you. The trailing consequence of further days and hours. No freedom from the past or future.” James Joyce wrote that “History is a nightmare from which I’m trying to awake.” How does writing help this? Does writing about the events offer a glimpse of freedom or only soften prison of the past?

DS: That was an allusion to a T. S. Eliot quote. But writing does help; it has been helpful for me. I used to subscribe to what William Gass said, that if you write well it cannot be cathartic, because you are working too hard. But after writing the memoir, I have to say that either Gass was wrong, or I didn’t do it well. Because it was completely cathartic. It has helped me smooth over the psychic bumps which accumulated from the accident. It helped me heal. I didn’t want to be a self-help book author, but I guess if you write well about these kind of things, the book can be self-helpful, in a way.

RF: What are you working on now?

DS: David Lipsky and I are collaborating on a young adult adventure series. I’m also working on a new novel that’s a mix of everything I’ve done to this point. The book is contemporary and historical and even a mix of fiction and non-fiction.

RF: In your opinion, can writing be taught? Also, and I think these questions are related, is it perseverance or talent?

DS: I think this whole argument, writing can’t be taught, is ridiculous. Yes, few people are super-brilliant writers once they graduate. Is that really a useful expectation, though? You don’t graduate from law school and instantly become Clarence Darrow! Does that disqualify law school? If you do not graduate among the top one percent of lawyers in the world, did law school fail you?

Does an MFA make you, magically, Philip Roth? No. It’s not a practical degree, but I tell students that if you really want an MFA, go where you can afford to go. Go to a school where you can get money to attend.

I also think you need to go to school where the writers you like teach. The economic truth of writing is that you’ll likely have to teach, even if you do publish your books. Even the incredibly successful writers, for the most part, teach. Junot Diaz, Jonathan Safron Foer and Zadie Smith all teach—in fact, they’ve all taught with me at NYU.

But if you can’t afford it, don’t go. You won’t just be able to hang a shingle on your door when you graduate and start making money. But, certainly, yes, writing can be taught. You will improve, you will—if you work hard in grad school—get closer to the last limits of your potential. If you go into it with that expectation, and you know there are no guarantees, and you still want to go, and can afford to go, and end up getting into a good program, then do it.

RF: Keith Lee Morris once wrote, “A father is anyone with answers to the questions that keep you awake at night.” I interviewed him and asked him this question. I’m now going to ask you: Do you think this is the writer’s task, to answer the questions that keep us awake at night? (Interviewer’s Note: Morris, in his answer, talks about exploring and not having all the answers. I didn’t want to give him a bad rap on this one!)

DS: No! It’s a nice line. It sure sounds good. Here’s a plainer one. A father is someone whose sperm helps create a child. I don’t know—I don’t have many answers.

The truth is, fiction writers shouldn’t have too many answers. Debate team captains have answers. Literature is its own way of thinking about things, as Milan Kundera said. Stories that purport to have an answer are not fiction; they’re propaganda. It’s an easy thing to say the answers. Literature transcends answers. Its job is not to tell you what’s right or wrong, but to show how everything is a little bit of both.

—Richard Farrell

Fascinating interview with an amazing author! Very interesting what he says about spirituality and writing — and why he couldn’t have written “Half a Life” as a novel.

Great interview Rich! Especially when Strauss said reading Tolstoy is like getting full strength brain vitamins. Reminded me…so i’ve pulled The Death of Ivan Illyich for a little shot.

Rich, thanks for sharing this interview. I read Half a Life and was quite impressed with Strauss’ honesty. And, I had never read a memoir from the perspective of the so called perpetrator (I use the word perpetrator taking into consideration that Strauss was completely innocent). It’s always nice to read interviews of other writers, as they reveal the laid back, off the cuff kind of stuff we don’t always get when reading books. I particularly appreciate Strauss’ stance on writing Half a Life as a memoir versus a novel – I agree that, as a novel, it wouldn’t offer the respect due Celine. I actually wrote a book review on his memoir for Brevity back in December – issue #38. If you’re interested, check it out at http://www.creativenonfiction.org/brevity/bookrev.htm. Thanks again!

Nice interview, Rich. I particularly like/relate to Strauss’ idea of spirituality in writing: “there’s something almost liturgically intense in the best writing”…I find it funny, however, the way sucessful writers often warn writers not to spend money on an MFA…I think the MFA was a great investment.

Fantastic and smart interview, Rich. I’m going to share this with my regular students because there is something in this for every single one of them. Something for all of us, whether as reminder or lesson. Thank you.