Here is a brief, sweet, melancholy memoir of Italy by my Italian-Canadian-singer-composer-writer friend Genni Gunn who lives in Vancouver but has a foot, a hand, a heart, still in southern Italy. She last appeared on these pages with an excerpt from her novel Solitaria which was long-listed for the prestigious Giller Prize.

dg

§

I’m in a rented car, at a railway crossing on the outskirts of Rutigliano, in southern Italy, when the train passes and the squeal of its wheels on metal transports me to a time before my birth, to a 1940 night sky in Locorotondo, where from her room my aunt Ida watched trains emerge and disappear into the railroad cutting in front of my grandparents’ house.

It’s May 2007, and I’ve spent the last month at the bedside of this aunt who, over the past five years, has told me her life story so often, I have begun to appropriate it, weeping and laughing in all the right places, mouthing the words right along with her. Ida is the guardian of our family stories, our oral historian. She claims absolute knowledge of everyone – despite my mother’s objections – and will recite particulars from all our lives, in dramatic arcs, complete with dialogue – mythologies which are difficult to prove or disprove.

I have been taking daily drives into the countryside to escape the weight of her past which, for the most part, Ida recounts in tragic, melodramatic tones, ending in maudlin, self-pitying sentences such as, “Oh how I’ve suffered!” and “I have worn out my threshold of pain.” During these afternoon drives, I can breathe deeply, unencumbered by her reproach which feels directed at me, even though her stories occurred decades before my birth.

I cross the tracks, and continue along the highway. At either side, rows upon rows of vines spread their arms beneath the mammoth nets that protect the grapes from hail, like prisoners praying for rescue, their legs tied, their heads back, faces to the merciless sun. As I drive on, the sky darkens with thunderclouds, and a surge of excitement – a memory – presses against my temples. I follow it to Locorotondo, tracing the map in my aunt’s head, the map of a young girl walking to school in the morning snow, flanked by her two brothers, Pippi and Alberto, all of them in paper-thin shoes and rough hand-knitted sweaters, all of them happy, carefree, Ida tells me, in a way she’s never felt since.

I approach the town from the north, drive up into it, up up past the school where Ida spent that year teaching small children, past the overlook at the park where old men on benches stare at the sprawling valley below.

My grandparents moved here in July of 1940, a month after Mussolini declared war on the Allied Forces. As a trackman, and also because of his difficult nature, Nonno had been relocated so often, his seven children – of whom Ida was the eldest – were dizzy with disruptions, unable to make friends, and weary of strangers, who constituted everyone outside the family. It explains, perhaps, Ida’s melancholy, her persistent memory, although she attributes it to Fridays – the day of her birth – which she tells me is unlucky, because it’s the day Christ died. A day of superstitions, she says, a small ironic smile curling her lips. Back then, people did not shop on Fridays or begin new projects or sign contracts or plan feasts. On Fridays, she tells me, people did not marry, nor did they baptize their children. If a man shaved on a Friday, he would be betrayed by his wife, or he would become widowed at an early age, and he who cut his nails on this day, would have to gather them on Judgement Day. One did not go visiting, send gifts, nor buy clothes, and if the first day of the year was a Friday, there would be wars, tempests and a thousand other natural disasters. Furthermore, she tells me triumphantly, children born on Fridays can expect to cry often during their lives – and this Ida has proven to be true.

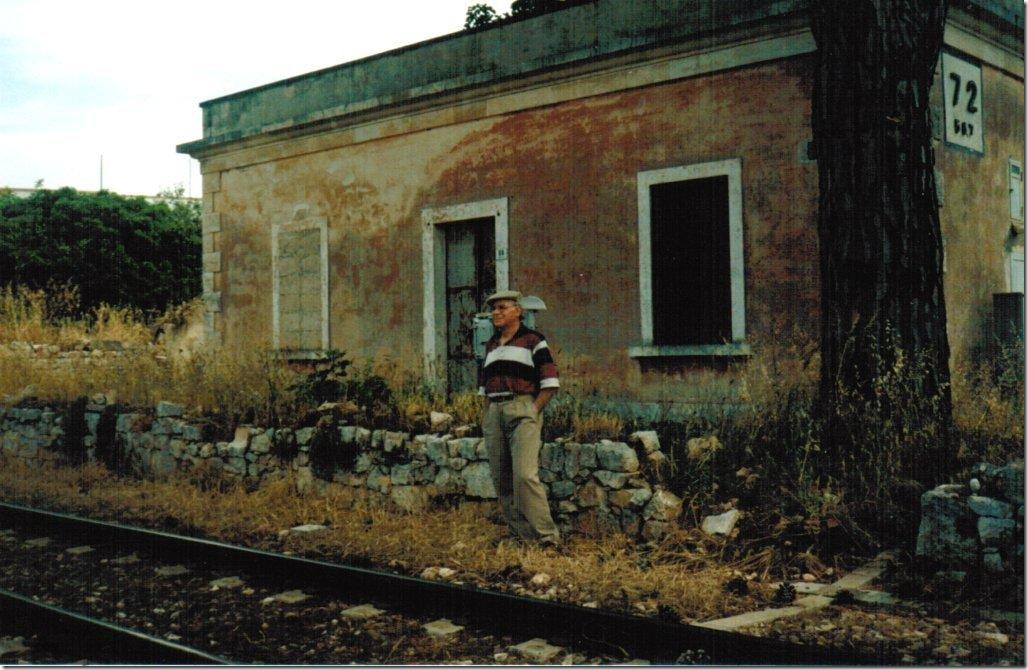

My grandparents’ Casello Ferrovia #72 – the trackman’s hut – is situated next to a railway crossing, the tracks of which wind below the hill, two kilometres from Locorotondo, in the Valle d’Itria, a karstic depression, not actually a valley, but a firmament of green hills and vales studded with over 20,000 trulli – the white conical ancient dwellings – and with limestone farmhouses. Locorotondo – round place, as the name suggests – is one of numerous marvellous towns found throughout southern Italy, built on hilltops, and fortified by immense walls and towers. Inside are medieval cities, all wonderfully preserved. From the highways at night, these towns look magical, lit up and round like multiple nativity scenes. In the daytime, Locorotondo rises four hundred metres above sea level, one of three natural balconies that surround the valley, and from which one can admire the Mediterranean brush, an indigenous vegetation that includes groves of Macedonian, bay and holm oak, laurel, myrtle, hawthorn, lentisk, wild olives and black orchids. Nowadays, this valley is a patchwork of stone stitching an infinite number of handkerchiefs of red earth, dominated by vineyards and country estates. When my grandparents lived there all those years ago, however, they knew nothing of castles or monuments, didn’t realize those oaks were 800 years old. All they saw was a pervading green, stone walls built without mortar, fields of red poppies and yellow daisies. And at night, outside their window, the town appeared suspended in darkness.

It takes several tries before I can decipher how to reach the casello. I have to return to the lookout, to fix my memory – my aunt’s memory – on the green on green, forget the new developments, the villas, and the asphalt roads which slice through the valley, and concentrate on the wild brush, the faint chugging of a steam engine in my head. Finally, I spy a dirt trail that circles to the right, and following it, soon find myself in Ida’s youth, surrounded by small limestone walls covered in lichen, fields of forage swaying, and bunches of red poppies growing amongst the rock. I follow the railway tracks directly to their casello which stands exactly as it did when she was young – red, its number plainly visible. I park the car and walk on the two-foot path beside the tracks, around the circular waist-high wall to the front. On these paths, Nonno rode his bicycle to work, and each morning, the children walked to the station more than a kilometre away, to catch the train for school. On this path, in the cutting which rises high above my head, my aunt learned about the earth, about rocks, stratification, about fossils visible in the limestone. They seemed wider back then, she tells me later, welcoming, these paths which led them into the world outside the family, paths which in memory have expanded both in size and significance.

The casello itself is changed and yet the same. One of the windows has been bricked in, and against the wooden door is a padlocked steel grate. At the back, the oven gapes like a yawn in the afternoon sun. I lean my head in and close my eyes, imagining the children’s mouths watering, breathing in the distant scent of Nonna’s bread on Mondays. They were allowed only one slice a day, “until the war ends,” Nonno said, and the children dreamt of loaves of bread. They had so little, even their dreams were small. It seemed a marvellous childhood, Ida tells me, we were dying of hunger, we had fleas so large we had to smash them with hammers, we had mosquitoes that ate us raw, and yet everything felt normal at the time. We had bread, and a house to live in, and we were very fortunate. As well, because we didn’t know anyone who was wealthy, we had no comparisons to make. Not like now, with TV, where everyone knows how the wealthy of the world live.

I walk around the small circular yard surrounded by stone where for one summer, Nonno grew tomatoes, zucchini, eggplant, potatoes and onions, where Ida planted geraniums between the rocks. None of this is evident now, the earth reclaimed by nature’s wild grasses and flowers. Everything dwarfed by age, but I have only to close my eyes, and the casello is vivid with their nine lives, with their perfect happiness constructed inside my head.

Across the tracks from the casello, a small road leads up and over a rise. I follow it, past the abandoned trulli where decades ago lived a young woman who grew red roses – flowers my aunt had never seen before – past a carrozzeria – a fairly recent car graveyard surrounded by a chain link fence, past wild trees of cherry, almond, fig and hazelnut, past the sprawling sculptures of flowering cactuses, imagining the taste of fichi d’India – prickly pears – of my own youth, past swishing biada and gold lichen on the white white walls, heading for the end of the road, toward a story my aunt has told and retold so often that I feel as if I, too, am part of that November evening in 1940, after supper, when Nonno and Nonna heard the sound of thunder in the distance. Nonna crossed herself and cast a worried look toward the smallest child, Alberto, who sat at the table drawing. He had been born during a thunderstorm, and she believed that babies born during a thunderstorm have a lifelong tendency to tremble, that they fear things will collapse on them, that their sparkling eyes cannot hold another’s gaze, that they have brilliant ideas and thoughts but cannot articulate them because they will always be thinking about thunder and the possibility of the earth breaking open and swallowing them whole.

The thunder continued, but sounded strange – at times like a punctuation, other times drawn out. “It’s a bombing,” Nonno said suddenly. “Get the boys up.”

Nonna and Ida quickly awakened all the children and together they ran up the hill to the top from which they could see the lights of the port of Taranto on the Adriatic coast, with its arsenal and shipyards, chemical works, iron and steel foundries and food‑processing factories. In the darkness, the thirty kilometres of verdant fields in front of them disappeared. Mario who read newspapers every day, told them that the entire Italian fleet was harboured there, and that Taranto was impenetrable, with its shoreline cannons and its metal nets under water, so that even submarines could not reach the ships.

But even as he said this, aeroplanes swirled in the sky like a flock of pelicans over a school of fish, and dropped hundreds of torpedoes and flares into the harbour. The Italian cannons fired back non-stop. Projectiles flew hundreds of metres into the air. The sky was ablaze, the air thick with thunderclaps. Every now and then, a deafening blast echoed underfoot, the sky brightened into an artificial dawn and they knew a ship had exploded. In that 1940 darkness, those spectacular, recurring bombings seemed like fireworks. The boys stared with shiny, bright eyes; they were childish enough to be fascinated by the idea of war, and fortunately too young to join. They hollered and sprang in the air, feverish with excitement, arms out, fists punching the sky. This, despite the fact that since the war had begun, Nonno had been listing the horrors, using his and his brothers’ experiences in WW I as examples – a completely unsuccessful tactic, given that unperturbed, the boys continued to construct guns and canons from which they launched pieces of wood and pine cones against imaginary foes which often included their siblings.

In the following day’s newspaper, they read, “Last night, a large number of British enemy torpedoes attacked the port of Taranto, extensively damaging numerous ships of our military fleet.” They were stunned. Hadn’t they been told Taranto was impenetrable? Wasn’t Italy going to become a superpower? Of course, they didn’t realize what the state-controlled papers did not say: that all the ships had been sunk.

My aunt went outside and crossed the tracks to the little country chapel across from the casello, opened the gate and knelt in front of the Madonna and Child frescoed onto the back wall. She understood nothing of politics – it seems impossible now to think that while atrocities proliferated around them, the family existed in a pocket of staggering ignorance. Ida says they were so poor and so hungry, for them the war was a phenomenon occurring in a distant parallel universe that had nothing to do with their inside world of babies and children, where the dangers far outweighed any external imminent one – Pippi could step on a rusty nail; Alberto could drink stagnant water and contract typhoid; Bruno could succumb to pneumonia; Bianca could slide under the rails of a train. They were constantly vigil. Living, itself, was a danger.

In that little chapel, my aunt prayed for everyone: for all the sailors who surely had been killed, for all their wives and children, for the British soldiers who had dropped the bombs, for their wives and children who would have to live with the knowledge of these deaths, for her siblings who seemed unbearably vulnerable, and for her mother and father who, she suddenly understood, couldn’t protect them from unspeakable evil.

I leave the hilltop, and walk back to the casello, past the country chapel that, with the exception of a locked iron gate, has remained exactly as my aunt described it, back to my air-conditioned car, imagining the sound of thunder, thinking how fortunate we are to never have witnessed war in our comfortable houses in Canada, to never have had to cower in our beds, expecting the sound of sirens.

I hear a train and quickly move off the tracks, experiencing a small moment of fear, like Ida must have – worried about the children, overly sensitive, overly morbid, always searching for the dark side of things.

The train is a pathetic old thing, four wagons only, all dirty and graffitied. I watch it turn the bend in the cutting, thinking how unlike what my aunt remembers, this decrepit train hobbling along, anachronistic in the wealthy landscape, the villas and superhighways nearby. I think how sad Nonno would have felt to see it, for surely it would have diminished him to witness its uselessness. And I think of my aunt, and for a moment, I feel the depth of her sorrow, her premonition that everything is gone, and that her awareness sprung of that night in 1940 was merely the beginning of a long line of disillusionments that would populate the rest of her life.

—Genni Gunn

—————————————————————

GENNI GUNN’s nine books include three novels – Solitaria (long-listed for the Giller Prize), Tracing Iris and Thrice Upon a Time; two story collections – Hungers and On the Road; two poetry collections – Faceless and Mating in Captivity; and two poetry collections by Dacia Maraini in translation Devour Me Too, and Travelling in the Gait of a Fox. Her opera Alternate Visions (music by John Oliver) was produced in Montreal in 2007. Her works have been translated into several languages, and have been finalists for the Commonwealth Prize, the Gerald Lampert Poetry Award, the John Glassco Translation award, and the Premio Internationale Diego Valeri for Translation. She lives in Vancouver. This memoir, without the lovely photos, was published by Wolsak and Wynn in Slice me some truth: An anthology of Canadian Creative Nonfiction, September, 2011.

I lived in italy 18 years ago and my memory of that seminal year is sharp but not nearly as mesmerizing as Ms. Gunn’s evocation of place and generations that are quietly disappearing. Italy is like a million universes unaware of each other’s existence but still connected by a dark shadow and an ever strutting sun.

Thank you for reading. And what a lovely way to put it.

I think, however, that all those universes might well be very aware of each other, connected and disconnected through traditions and customs, complex and multi-layered.