Wong Kar Wai’s 2046 is the story of Chow, a writer and Casanova in 1960s Hong Kong who writes a science fiction serial titled “2046” that he publishes in a newspaper. Several of the women Chow has known, loved, resisted, and spurned appear as androids in the vast, glittering, futuristic yet nostalgic science fiction serial he writes. Chow connects these two narratives and so writing and desire, space and time, imbricate and refer back to him.

When the protagonist of Chow’s serial, Tak, proclaims his love to one of these androids and asks her to leave with him, she does not respond until many hours later when she is alone. Critics like Mitsuda and Martin read this delay as the absence of emotion, as a cold, embittered detachment. Against this, the delay the androids experience does not negate the emotional response. They are not impervious to emotion, just slow to express. This delay is a precondition for the preservation of desire, and, ultimately, this delay refers back to Chow’s originary unrequited desire and the secret he will never know.

2046 opens with Tak, the protagonist of Chow’s serial, a man on a train traveling through a futuristic cityscape. He wonders how long it will take him to leave 2046, a place, he explains, where people go to “recapture lost memories . . . [ where] nothing ever changes . . . Nobody knows if that’s true . . . because nobody’s ever come back . . . except me.” Tak, then, is a man who is trying to escape memory and, it seems, is choosing or desires forgetfulness. He confesses that he has chosen this path because 2046 didn’t give him what he wanted:

“I once fell in love with someone. After a while, she wasn’t there. I went to 2046. I thought she might be waiting for me there. But I couldn’t find her. I can’t stop wondering if she loved me or not. But I never found out. Maybe her answer was like a secret . . . that no one else would ever know.”

Tak the traveler is seeking to leave 2046 and choose forgetfulness, but he cannot give up on the lost beloved’s answer, one he describes as a secret “no one else would ever know.” It is unknowable, but he fantasizes that it might mean she answered him back.

“unshareable secrets”

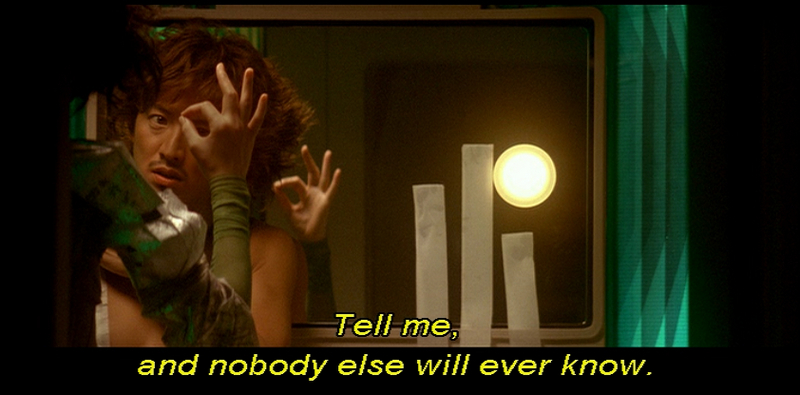

When Tak, in order to keep warm on the train, embraces one of the android attendants and finds he desires her, he seeks escape, forgetfulness and answers. All this distills down to one luminous desire: to tell a secret. He explains this to the android: “Before . . . when people had secrets they didn’t want to share, they’d climb a mountain, find a tree and carve a hole in it, and whisper the secret into the hole, then cover it over with mud. That way, nobody else would ever discover it.” His android responds by making a circle with thumb and forefinger, holding it out to him.

She offers, “I’ll be your tree. Tell me, and nobody else will ever know.” But as Tak tries to tell the secret to her outstretched hand, the android keeps moving the tree, the witness, teasing. Until the site of listening becomes her mouth. A kiss.

“secrets as questions”

For Tak, the secret he seeks to tell and the android he seeks to tell it to are related: “I once fell in love with someone. I couldn’t stop wondering whether she loved me or not. I found an android that looked just like her. I thought the android might give me the answer.” For Tak, the secret is a two part question: first, does the android know the secret of this other woman’s desire, this woman she resembles; second, does the android desire him back. The android promises the return of the secret, the possibility that the unknowable will become known, the unrequited might become requited.

But when he asks the android to leave with him, he discovers that the android does not respond. The conductor of the train explains that, “When [androids have] served on so many long journeys, fatigue begins to set in. For example, they might want to laugh, but the smile would be slow to come. They might want to cry, but the tear wouldn’t well up until the next day. This one is failing fast. I think you’d better give up.” The declaration given in the moment of the kiss, the secret given to the tree, receives no immediate response, but still holds the promise of a delay.

“literary intentions”

To understand the meaning behind this delay, we need to look at how Tak is a protagonist in a work of fiction called “2046” created by the true protagonist of the film, Mr. Chow. Chow writes this fiction at first for Miss Wang, the daughter of his landlord who he finds next door in the room numbered “2046.”

When he meets her she is heartbroken, longing for her Japanese lover. Chow says he writes the fiction to explain for her the perspective of the Japanese man she loves:

She was always asking if there was anything at all that never changed. I could see what was on her mind. I promised to write a story for her based on my observation. Something to show her what her boyfriend was thinking. . . . So I began imagining myself as a Japanese man . . . on a train for 2046 . . . falling for an android with delayed reaction.

Tak, then, is both a version of Miss Wang’s Japanese lover (which Wong indexes by having the two roles played by the same actor), but he’s also a literary avatar for Chow, enabling him to get closer to her, to pose as her beloved.

“the delay of letters”

The delay that occurs between the android and Tak mirrors two obstacles between Miss Wang and her Japanese lover in 1960s Hong Kong. It is, perhaps most obviously, the delayed communication between the two lovers who have to communicate via letters because Miss Wang’s father has forbidden their love. The act of letter writing involves a delay we are barely familiar with in an era in which we can text message the beloved and he or she receives our words in mere seconds. The Japanese lover expresses sentiment on the page one day and Miss Wang receives and experiences an emotional response weeks later. Letters can bridge the lovers and overcome distance but only by creating a delay where the beloved waits to respond.

This delay then is a question of waiting and waiting is about desire. Roland Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse meditates on this waiting and connects it to desire: “Am I in love? – Yes, since I’m waiting.”

“delay and waiting”

Barthes adds a small tale about the lover and waiting:

A mandarin fell in love with a courtesan. “I shall be yours,” she told him, “when you have spent a hundred nights waiting for me, sitting on a stool, in my garden, beneath my window.” But on the ninety-ninth night, the mandarin stood up, put his stool under his arm, and went away (40).

Similarly, Anne Carson in Eros: the Bittersweet points out that “A space must be maintained or desire ends” (26). Miss Wang’s letters from her Japanese beloved, and by extension the android’s delay in responding to Tak’s declaration of love, on one level signify separation, distance in time and space, but on another create and perpetuate desire. Waiting is the point.

In addition to the space between Miss Wang and her Japanese lover and the time it takes for their words to reach one another, other obstacles of time and space interrupt, contribute to the train of desire. Because even their correspondence has been forbidden by her father, Miss Wang asks Chow to intercede, to help by sending her letters and by letting the Japanese lover write to her via Chow’s address so her father won’t know. Miss Wang and her lover’s words and letters must traverse Chow as agent, as constituent, as conduit. The amorous epistle is further delayed.

“delay and translation”

This delay is exacerbated by the space between languages and the difficulties of translation. When the Japanese lover asked Miss Wang to go with him, her response was delayed much the same way the android’s response to Tak is delayed. When Chow first meets Miss Wang she is in the room next door, the room suitably numbered ‘2046,’ pacing and rehearsing the response she never gave:

“Let’s go . . . I’ll go with you . . .I understand” she repeats over and over in Japanese. The specter of language difference emphasizes the possibility of miscommunication and mistranslation between lover and beloved.

“the lover’s discourse”

So even if the letters could arrive directly, immediately, without delay, there would be the problem of language for the lover. As Barthes asserts in the opening to A Lover’s Discourse, “the lover’s discourse is of an extreme solitude . . . it is completely forsaken by the surrounding languages: ignored, disparaged, or derided by them, severed not only from authority but also from the mechanisms of authority” (1). Miss Wang’s delay, her inability to respond to the Japanese lover might too have been an effect of this obstacle for the lover seeking to declare love. All declarations of love in 2046 then are part of a system of delays and inescapable obstacles. The lover has to wait, for this is what makes him or her a lover.

For Chow, though, this delay that he imagines and writes into the serial fiction called “2046” is partly a representation of his own growing interest in Miss Wang and her apparent indifference. When in the serial fiction Tak rhetorically asks the conductor on the train, “Who’d ever fall for an android?” the conductor replies, “Who can say? Events can creep up on you without you ever noticing. It can happen to anyone.” This is precisely what Chow himself confesses in the voice over that frames Tak on the futuristic train when he realizes he is falling for Miss Wang: “Feelings can creep up on you unawares. I knew that, but did she?”

“promise of reciprocity”

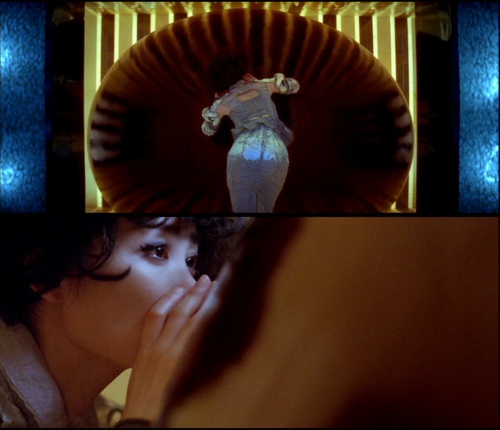

Chow writes a complementary secret into the narrative where the Miss Wang android not only weeps in her cabin on the train, but also goes to a space on the train reserved for secrets.

This circular shaped object with a space in the centre recalls the tree Tak told the android about. So the android not only has a delayed emotional response, she also has her own unknowable secret. This stands as the promise of reciprocity, but, as unknowable, remains forever uncertain.

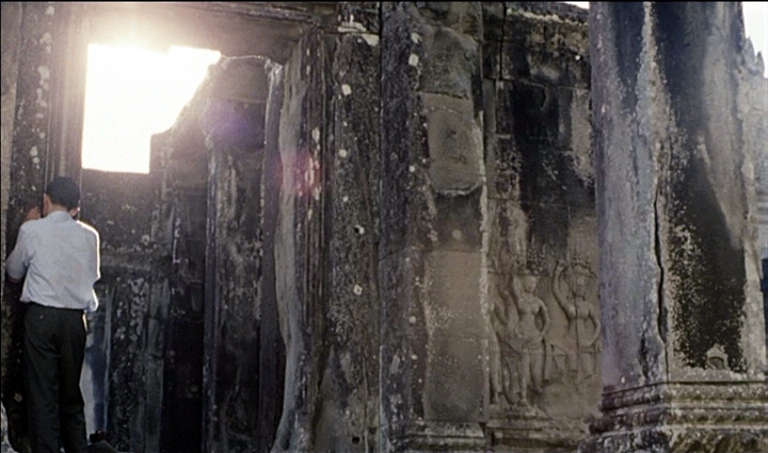

These two secrets – Tak’s told to the android’s hand, and the android’s told to the futuristic tree on the train – both intertextually reference one originary secret in Wong Kar Wai’s previous film In the Mood for Love.

“the originary secret”

In that film, another character named Chow, also played by Tony Leung, also recalls the mythology of unshareable secrets and at the end of that film he whispers his secret to a hole in some ruins and covers it up.

This secret recalls the first narration of 2046, when Chow’s voice explains why Tak went to 2046: “I can’t stop wondering if she loved me or not. But I never found out. Maybe her answer was like a secret . . . that no one else would ever know.” For Chow, then, traveling to and away from 2046 is not just about his growing desire for Miss Wang. It is also about this other unrequited desire, for Mrs Chan, the unobtainable married woman he loved in In the Mood for Love. In an odd and perfect turn, Mrs Chan from also appears in 2046 as an android.

His secret declaration, whispered into the ruins, desires reciprocation, an answer, the possibility that Mrs Chan’s desire was also declared in a secret. Thus, she might still respond, the unrequited might still be requited.

“love letters”

What the delayed response draws attention to, then, is not the android’s delay, something we might analyze in her circuitry, but instead the nature of these secrets. Tak’s declaration, the secret he presses to her as a kiss, and the android’s own secrets whispered into the futuristic tree on the train are in essence love letters.

Barthes points out that “Like desire, the love letter waits for an answer; it implicitly enjoins the other to reply, for without a reply the other’s image changes, becomes other” (158). Here, what is essential, is that the reply not other the beloved for that would in effect end the amorous discourse.

Chow writes “2046” to preserve the possibility of the answer and the beloved’s return. What is at stake here, though, is not reciprocation or the possibility of a requited love so much as it is survival. As Barthes argues about the lover, “language is born of absence: the child has made himself a doll out of a spool, throws it away and picks it up again, miming the mother’s departure and return: a paradigm is created” (16).

“there / gone”

Barthes borrows this metaphor of the child and the spool from Sigmund Freud’s analysis of his grandchild’s “fort / da game” (fort / da translated means “gone” and “there”) where he overheard the child calling out “Fort” and “da” – and interpreted this as negotiating the mother’s absence.

To master “there” and “gone,” the beloved’s absent presence, is core to Chow’s writing act with “2046”. This game, this evocation of the beloved as present though absent, Barthes argues, “postpones the other’s death . . .To manipulate absence is to extend this interval, to delay as long as possible the moment when the other might topple sharply from absence into death” (16).

Chow writes “2046” to keep desire alive, to postpone the perhaps inevitable end of desire and loss of both Mrs Chan and Miss Wang.

“Happy Endings”

This game of absent presence, this preservation of desire becomes most apparent when Miss Wang goes to Japan to be with her Japanese lover. She sends a message back to Chow through her father, asking for him to write a happy ending to “2046.” In the scene that follows, Chow remains frozen, his pen hovering above the page.

The titles tell us he sits there for one, ten, a hundred hours. Chow cannot write a happy ending, not even for Miss Wang. Further, how can he write an ending to a serialized fiction – the very form is about waiting, for the next installment and for the eternally delayed catharsis of an ending. This is what blocks his writing, leaves him paralyzed, the pen hovering over the page. For in essence to write that happy ending would be to foreclose on all his unrequited desires, would sever the myriad connections to his original loss, his original unrequited desire in In the Mood for Love.

In Wong Kar Wai’s 2046, the android Miss Wang’s delay does not indicate an absence of emotion. She must delay and hold the promise of return. To read her lack of a response without the delayed emotion is to miss the point, to not see how the android is in essence programmed to sustain the unrequited love and protect the lover from the possible loss of the beloved. If Miss Wang will ever reciprocate, if Mrs Chan will ever return and love him back, if desire is to continue on its unrequited path always away from oblivion and ending, the eternal delay must go on.

— R. W. Gray