Editor’s Note: Melissa Fisher’s “My First Job” essay won the 2012 3 Quarks Daily Arts & Literature Prize competition judged by Gish Jen. Gish Jen wrote: “This memoir of growing up in Vermont begs to be turned into a book. At once deeply universal and deeply strange, it is wonderfully unpretentious, completely appalling, and appealingly clear-of-heart.”

Melissa Fisher, already “a person of interest,” as the police say, for her satirical photo essay “And the Sign Said” now offers us a “My First Job” in which she manages to insert blood, mayhem, drunkenness (not the author), underage driving, romance (the brown-haired boy) and a gorgeously hilarious picture of growing up a girl in rural Vermont. Nothing more to be said. Read it.

dg

.

Out There

Growing up with eight older brothers, I had a feeling that I could do anything. I was keeper at soccer (not afraid to get kicked in the head if it meant making a save) and played first base, feeling pride in the shocking sting across my palm whenever anyone fired one in my direction. It was the Fishers vs. anyone else in the neighborhood, and I was always the only girl on the field.

When we moved to Vermont, expanding our summer camp into a home, we traded neighborhood friends for trees. Thousands of trees. Our nearest neighbor was a mile south down a single-lane dirt road that was often impassable in the winter. From our house-in-progress on Cram Hill going west, it was two and a half miles to asphalt, and the first house that way, a log home belonging to the Potters (their name spelled out in stones at the end of the driveway), appeared in the last half-mile. We had a quiet view of Granville Notch to the west without a structure or speck of light in sight for miles across the panorama. When weather shifted, a gray sheet of rain would spread across the valley toward us providing a 90-second warning to get the laundry off the line. Some days the only hint of civilization was a distant loon-like call of the train whistle twice a day, southbound in the morning, northbound at night.

The electric and phone lines didn’t reach us, and cell phones didn’t yet exist. We had a CB radio for emergencies. In summers when humidity was high, a skip allowed my father (his handle was Preacher Ed) to talk on the squawk box to southern drawl truckers hundreds of miles away. These were our only conversations with the outside world. We were out there. .

First Babysitting Job, Starts with the Pig Blood in the Yard

So when I was 10, perhaps out of boredom or arrogance, I didn’t see any reason to say no when I was asked to babysit two kids of a couple I didn’t know well (they also lived in a house without electricity). Later, I saw many reasons why this was a terrible idea, and I also questioned my parents’ judgment in letting me go. But the lure of two dollars an hour trumped any good sense I might have held.

My mother dropped me off in the driveway and backed around leaving me to walk to the house alone along a stone path that led by a stump steeped in blood with fresh blood lying in pools all around. Perhaps, I thought, I should have asked more questions, but how to prepare for this? When the father, John, opened the door, I turned back to wave and watch my mother’s car head down the driveway back home, realizing suddenly that I was a bit homesick, scared, or both. John explained the blood—I had just missed the pig slaughter. I wondered if I’d been expected earlier to help out.

The boys, blond-haired and shy, watched me suspiciously. This was our first meeting so I reached out to them slowly, the way I had with the stray before he became Snowflake, my mother’s favorite cat. It didn’t work with the boys as well as with the cat. Their mistrust lasted long after the parents left for the wedding, and we spent the afternoon only half-playing, half-wondering when the parents would reappear.

I was ten. I didn’t know what a babysitter did. I fed them peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, and we went outside and threw rocks. Boys like throwing rocks. When they’re not eating them they’re throwing them. We stayed well away from the front yard, the stump, the blood. I didn’t ask about the pig.

The afternoon dragged on. I only wanted to go home but had no idea when that might happen. I hadn’t been forward enough to ask exactly when John and his wife would return. They were vague. I had the impression it was going to be just a few hours. In my mind, they were coming home at two or three in the afternoon.

The boys moped, grieving abandonment. “Do you want to read a book?” I asked. “I want Mommy to read it to me!” “Do you want to go outside with the trucks?” I asked. “Mommy take me outside!”

By hour five, I had started to watch the driveway incessantly. I couldn’t call home, of course—in my world calling home wasn’t an option to consider–and I wondered why my parents hadn’t come looking for me. The boys weren’t the only ones feeling abandoned.

The boys refused to nap. I wondered if I should I walk them half a mile to the closest neighbor? I didn’t want to get the parents in trouble. Were they in trouble?

After 10 really, really long hours, and long after dark, headlights finally haphazardly probed up the driveway. When the boys’ parents came stumbling in, I was already at the door ready to go home. The mother drunkenly waved her arm (really her elbow) in the air and disappeared to bed. John’s head drooped. His eyes stared out without focus..

Heading Home, the Body in the Backseat

When we finally got into the beat up Toyota wagon, he mumbled something about watching my feet. At first, I didn’t know what he meant, it was dark, but soon I realized there was a hole as big as my foot in the floorboards. We didn’t talk. Something kept clunking in the back. Turn left, clunk right.

When we hit the pavement, I suddenly could see light at my feet. I watched a blur of the road between my heels. Lines would appear, some double yellow, some white. Back on the dirt road to my house, the clunking returned. Turn right, clunk left.

The driveway ended at the garage, but John drove across the lawn to the front steps. At last, with the dome light on, I could see a large mass in the back seat. I had been afraid to look. I had no idea it was a person. A toolbox maybe. When you live on the back roads things always clunk and roll around, but this was a big clunk.

“My brother-in-law,” John growled. “He’s a waste of oxygen.”

John walked me to the door—I was only ten. And all I remember after that is going straight to bed, climbing the wooden ladder to the curtained loft room that was mine. But my parents must have seen John’s condition because they invited him in and made coffee. At some point, the brother-in-law wandered in, disoriented either from the repeated head trauma or the unfamiliar surroundings..

Aftermath, More Babysitting, Animal Attacks, I Scar a Child for Life

Afterwards, my parents never said anything about that night, whether they wondered if I was okay. They rarely said what they felt. They seemed to accept John’s drunkenness without judgment. Oh, that’s just John… Somehow I can’t imagine parents being that open-minded today. And a few years later, when my 17-year-old brother arrived home late after school completely bombed on strawberry daiquiris, my father expressed his disappointment by grounding my brother for a month—a month alone out in nowhere without a phone; it was like solitary confinement.

It didn’t strike me odd that we’d have a drunk or two in the house. Rod, a neighbor well-known for his hundreds of junk parts cars in various stages of impermanence, would wander down the “thrown up” road (now more of a path) from his trailer a few times a year. He refused all food, lived simply on 16 oz. Budweisers or whatever other version of beer was handy. He was friendly, smelled of urine, booze and cigarettes, and said Jesus Christ more often than my father ever did in the pulpit. Rod had a bony chest and his Dickies hung belted at the waist, cinched around fumes. Rod’s granddaughter, Belinda, once bit me on the arm because I was using the bathroom. I wasn’t babysitting her. She was just visiting.

What does (did) surprise me is that my parents ever let me baby-sit again. But they did, many times. Through trial and error I learned valuable tips such as Kool-Aid is more complex than Tang and requires infinite scoops of sugar. And sugarless Kool-Aid on a picnic will destroy a child’s day and will ultimately be tattooed to his or her memory for the next 20 years. (I know because 20 years later I saw this person on the streets of Montpelier and his first words were, “Remember when you (tonal implication of ‘you moron’) forgot to put the sugar in the Kool-Aid?”)

B-Bet (short for Elizabeth) fast became one of my favorite watches and not just because I got to saddle up her mother’s tar-colored brute of a horse, Mischief, from time to time. Mischief tried to buck me off more than once and would very reluctantly go for halting walks. On the way home he’d gallop if given the chance. In my limited riding lessons I had only made it as far as a delicate posting trot on a pony. I was afraid even to canter, but I’d learned to hold on like hell.

B-Bet always had to come out to the car when I arrived to save me from Gus and Geezer, the geese watchdogs. Gus was one-legged and cranky. Geezer was particularly vicious and would make a spear of his body, aggressively flap his wings and repeatedly stab my legs with his beak. I’d yell to no avail. Two-year-old B-Bet would shake her finger at him, scolding, and he’d ashamedly retreat.

My best friend/rival Beth also babysat and we had our regulars. One of her families had a cute rhythmic ditty that the father sang to lighten moods: “Me-lis-sa-Fi-sher, ate-her-ki-tties. Me-lis-sa-Fi-sher, ate-her-ki-tties.” I have no idea where this came from. I had never spoken with this gnomish furniture-maker, though I knew he crafted beautiful stuff. Understandably, his kids never spoke or made eye contact with me, either..

Crossing the Line into Criminal Behavior with Accomplice and Small Children

The family I babysat for most often had two charming girls, one of whom once fondly asked me, “Why are you so fat?” At first, I’d put Meredith to sleep in the crib and then read to two-year-old Stephanie. She would make me read every single book at least once and instantly scream if I stopped for the briefest moment, threatening to wake the baby.

After they were both in bed, I’d engage in battle with the wood cook-stove. I never understood the drafts. My two options were to keep it wide open, meaning the temperature in the old schoolhouse would quickly escalate to 95 degrees, or damp it down and fill the house with smoke until the fire choked out. Either way, I’d end up opening all the windows and doors.

I loved their parents, Steve and Jude. At nights on the drive back to my parents’ house, Steve would holler out, “ENGLAND!”then swerve and drive for half a mile on the left side of the empty road, a great belly laugh shaking out of him.

Stephanie and Meredith were terrible secret-keepers. Once, when I was 14, their parents left me the car keys for the day—for emergencies. Or perhaps so I could run to the Roxbury General Store for milk. Along with milk, the store had two well-stocked coolers of cheap beer, gas, a dome-covered cheese wheel, flies, penny Swedish Fish, Charleston Chews—best after being stuck in a snow bank and frozen solid—more flies and Atomic Fireballs but not much else.

I didn’t drive to the store, not at first anyway. Instead I called a brown-haired boy. Technically, he lived in the opposite direction from the store, but that’s fine. I just figured this would catch his attention. I loaded the girls in the car, popped in the Genesis Land of Confusion tape I found in the glove compartment, and headed for his house—choruses of “Where are WE GOING?” rising from the backseat.

I was actually a pretty good driver with three years of experience. My father had taught me to drive his Jeep when I was 12. Given where we lived, he’d been careful to explain about driving on washboards, how to do a hill start on loose gravel, and where to pick up the firewood he’d cut up down the road that needed to get stacked in the shed.

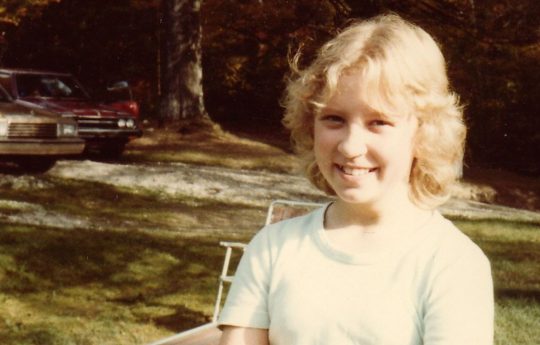

The truck I learned to drive in.

The truck I learned to drive in.

When he handed me the keys, Steve, the girls’ father, had pointed out that the car’s low gas light was on. But he was pretty sure there was enough to get to town and back if we had to. So when we picked up the brown-haired boy—and not wanting to get stranded—we carefully poured in some gas from a red can in the barn. Then, a bit horrified (a sinking, Oh shit! moment when the gas warning light FAILED to come on), we realized it was too much and proceeded to spend the afternoon driving every dirt road in town until the yellow dot on the dash reappeared. (Okay, it WAS a nice realization that we would sneak around all afternoon, driving unlicensed and free. And 14!)

We weren’t worried about cops. I had never heard of the Roxbury town constable doing anything more than grudgingly volunteering for the position at town meeting. Also I had heard and fully believed that regular laws didn’t apply to dirt roads (I think my father the minister was the one who told me this questionable fact). The locals who usually hung out on the store’s porch were in and out of jail for various bits of misconduct—we were known as an outlaw town—but I was never sure how they got incarcerated (this reminds me that my friend Anna used to call jail “Three Hots and a Cot”). When my mother and the planning commission tried to clean up the village, Dave Santee, who lived next to the store, fired up the “Uglification Committee” and promptly hauled a toilet, two rotting dormers, and a one-wheeled tractor to his front yard.

I was aware, yes, that I was taking advantage of the situation, and, being a respectful minister’s daughter down deep (very deep), I was really afraid of being caught. Steve, the father, was a playful and irreverent ex-hippie. He loved it when I was a little bad—he’d say, “Oh, I bet that pissed off Ed and Ellie” and laugh. I adored him and looked up to him, and I hated the idea of losing his esteem. Not to mention the fact that my father might have had some feelings on this one, too (though, clearly, he TAUGHT me to drive at the age of twelve and, if the truth be known, wasn’t averse to a bit of rule-bending now and then either).

Late in the afternoon, when it finally occurred to me that Steve and Jude would be appearing in the driveway any second, we headed for home. I threw the brown-haired boy out of the car at his mailbox, barely stopping. Then I casually, airily (and very carefully) discussed with the girls the fact that what we had done all afternoon was perfectly fine, normal, unremarkable and not worth mentioning to ANYONE. There was no reason to say anything about it to their parents, and besides, their parents wouldn’t care.

We pulled into the empty driveway, unloaded, and were lingering on the lawn when Steve and Jude arrived moments later. I was in a panic, the hood of the car was still hot, but ALL was well.

Then, suddenly, the girls were dashing toward their parents, screaming, ”Mommy, Daddy, Melissa drove THE CAR! We drove EVERYWHERE and finally the light came BACK ON! She told us not to tell you.”

I thought, Oh shit.

Steve said, “Is that right?” He looked right at me and laughed.

—Melissa Fisher

.

Melissa Fisher is a writer and college administrator still living in Vermont.

.

.

Ah, those first babysitting jobs. At age 10! (I think I started babysitting at age 10, too, but I sure wouldn’t hire a 10-year-old to take care of my kids nowadays.)

This piece is a striking reminder of how differently parenting is viewed these days compared to when I was a kid. wow.

Melissa, you’ve beautifully and humorously shared a rare slice of American life. I love these images of you as a kid waiting for the parents to return home drunk, and driving over dirt roads to use up gas.

Excellent, Melissa! This explains so much 🙂

Really, I love that this story of your childhood foretells your intrepid nature, how capable you are, how you’re a good person to have around when all hell breaks loose, (read: residency), and how little seems to surprise you. I, too, babysat, but had no smoking woodstove, combative geese, or recalcitrant horses to contend with. Only drunken fathers who drove me home so smashed I’m surprised I’m still alive, and bored children who I’m sure I failed by being less lively than perhaps I ought to have been. No dead pigs, either, in my past. Not until I went to school in Montana, where seeing slaughtered deer lashed to pickup trucks was an everyday affair.

Palpable and evocative. And very very funny.

There are a lot of great images and lines in this piece, but my favorite is “his Dickies hung belted at the waist, cinched around fumes.” I know people who look like that and never had a way to describe them, until now.

My favorite line too. Right after I read it I repeated it out loud and laughed some more. Great writing, don’t stop.

Thanks, Liz and Daniel. Rod’s visits were always unexpected and fascinating. Quite a substitute for TV… I wonder who was more curious about the other, my parents or Rod?

Absolutely the best line! My thoughts exactly as I read and re-read it. What a marvelous piece of writing. The piece grabbed me by the throat.

Absolutely awesome, Melissa. Outlaws, geese, slaughtered pigs, trucks with holes in the floor, irreverent ex-hippies: this is my kind of Vermont. Where’s the BOOK?

Harrowing. That’s the word I kept thinking. Those ten hours made my skin crawl! This is wonderful, Melissa, evocative, terrifying, dark and funny (love the parenthetical asides.) Thanks for sharing this. It’s amazing you ever babysat again after that first time.

“I was ten. I didn’t know what a babysitter did. I fed them peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, and we went outside and threw rocks. Boys like throwing rocks. When they’re not eating them they’re throwing them. We stayed well away from the front yard, the stump, the blood. I didn’t ask about the pig.”

My nearly 10 year old daughter still seems so young to me. So many great images, the kool-aid, the guy driving on the left side of the road. This totally sucked me in and wouldn’t let go. Wonderful writing, wonderful essay.

Melissa, thanks for sharing the essay. Eight older brothers? I can’t believe it. Great characters here. There is so much more of this story I want to know now. As for many, this essay opens a pandora’s box of memories (having also started babysitting when I was 11 for children only one or two years younger than I … what were people thinking? Now it seems parents expect at least a Bachelors degree with an emphasis in early childhood development).

Oh, Mel! That was beautiful! I felt transported, not to my own childhood (although you evoked memories there, to be sure) but to YOURS, which is a far more amazing thing. It makes me a bit sad to think that, living up there in isolation from the rest of the world, we failed to connect more with each other. I blame you. Just kidding. Really I think it might be that we went into some sort of survival mode; maybe if the three of us had banded together to fight the boredom and the loneliness, we would somehow have made them more real. But I digress. Your piece gave me chills. You manage the rare trick of writing poignant memoir without a trace of self-absorption or false modesty. It’s gently philosophical, wistful without melodrama, and a total hoot. If you don’t expand on it and publish it in fuller form, I’ll kill you. Not really.

Very nice.

I am with Robin (the pink one): Where is the book?

And with Eric when he comments on the memoir sans self-absorption or false modesty – so right. A delightful read that left me wanting more, much more.

This is wonderful, Melissa! As Robin says, no wonder you are so capable! I love how accepting you were of the challenges flung at you like soccer balls. A beautifully written and fascinating story!

Babysitting at age ten, for $2.00 an hour. Wow! You really raked it in! I remember when I thought $.75/hour was a big deal. That and whether or not the fridge and cupboards were stocked with stuff my mother never bought (like coke and fritos).

This was funny, ironic, bittersweet.

Thanks.

Wonderful! and it brings back so many memories. When girls could deliver newspapers because it was considered too dangerous for us to go to people’s front doors, but we ended up spending late nights babysitting at the homes of some of the creepiest, scariest people in town. I miss you, Melissa! so I loved your virtual visit.

Melissa what a wonderful, funny, voiced, ironic, evocative piece! I’m missing residency already so this was a real treat.

Congratulations, Melissa! You have won first place in the 3QD Arts & Literature Prize for 2012. Do come over and leave a comment at 3QD.

Best wishes,

Abbas

Wonderful news! Thank you, Abbas.

Oh, here is the prize announcement: http://www.3quarksdaily.com/3quarksdaily/2012/03/the-winners-of-the-3qd-arts-literature-prize-2012.html

Congratulations Melissa! I am so pleased for you!

Hi Melissa. I loved your piece. Congratulations on winning a terrific award! Middle grade book – bring it on!

Gosh, I think it’s best if I leave the MG writing to the experts. How you all do it, I’ll never know…

Really great piece Melissa. It’s hard to imagine that you didn’t grow up at the turn of the century. Seriously funny. Congratulations.

THAT explains why I’m still not on Facebook… 🙂

Melissa!!! I adore this piece:) So evocative and compelling; I was right there with you (rather your younger self) on all of these hilarious VT/babysitting adventures. Rich, rich descriptions and all truly funny, fun and poiginant. Congrats on your win; clearly well-deserved!

Fantasic Melissa,

what writing and storytelling…!!

Thanks, Lili. What a nice surprise to see you here!

Great peice; and of course brings up my baby sitting experiences. One of my first was 2 horrible little girls who I literally had to sit on, to make them stay in bed. The parents came home so late that my worried mother, came and took me home. Then went back to the house to meet the parents who eventually arrived drunk and in the early morning. Quess what? They even wanted me to baby sit again, not at all intimated, but assuring that they wouldn’t be back so late.

I only had 4 brothers but I also would be the only girl on the baseball team as I could hit homeruns but not catch, so I would be put way outfield.

thanks so much, Molly

Hi Melissa: The true beauty of your story lies in its honest, authentic voice. Good work! Write more! Great to meet you on our crazy road trip. We sincerely hope you will visit us soon in Canada.

Kathy

Melissa!! I loved this!!! Amazing !it brought me back. I miss those days. I miss you. Where are you?

Beth, I have forwarded your email address to Melissa.