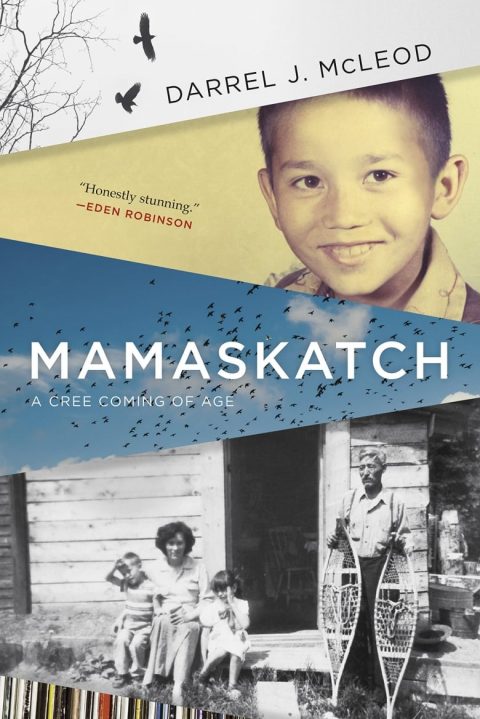

A lovely bit of news and another example of the magic that used to happen around the magazine: Darrel J. McLeod, a Cree writer from Sooke, British Columbia, in October won the Governor-General’s Award for Nonfiction for his autobiographical book Mamaskatch, A Cree Coming of Age. First off, we need to congratulate Darrel, whom I got to know three years ago. He’s a warm, unassuming, humble man with a story burning in his heart.

As it happens, we published Darrel’s first short story in Numéro Cinq in the October, 2015, issue. After the GG announcement, I was reading about Mamaskatch and something clicked. The same names were appearing in both texts. And I remembered that Darrel had told me all the characters and events in the story were based on his family. So I dug around a bit more and found this graceful credit line in an interview Darrel did for the Vancouver Authors Festival in September.

I concluded the story “Hail Mary Full of Grace” at a week-long workshop with Shaena Lambert in the summer of 2014 – you were there Jen, and you were so incredibly helpful. I was thrilled with the final version of the story, and submitted it to Douglas Glover for publication in Numéro Cinq. After helping me to find a better ending, he published it, but I knew I wanted to include it in my memoir as well.” Q&A with Darrel J. McLeod

Shaena Lambert, in fact, brought Darrel to me and the magazine. She had quickly recognized his talent and thought of us. And that’s the story, a circuitous story, a wonderful story, of how Numéro Cinq came to publish the first short story by a Cree writer in Canada and that short story became part of a Governor-General’s Award winning nonfiction book.

The story is called “Hail Mary, Full of Grace” and you can click on the title here and read the entire piece. Or you can buy Darrel’s book and read that. Or you can read both.

Here is the publisher’s description of the book:

Growing up in the tiny village of Smith, Alberta, Darrel J. McLeod was surrounded by his Cree family’s history. In shifting and unpredictable stories, his mother, Bertha, shared narratives of their culture, their family and the cruelty that she and her sisters endured in residential school. McLeod was comforted by her presence and that of his many siblings and cousins, the smells of moose stew and wild peppermint tea, and his deep love of the landscape. Bertha taught him to be fiercely proud of his heritage and to listen to the birds that would return to watch over and guide him at key junctures of his life.

However, in a spiral of events, Darrel’s mother turned wild and unstable, and their home life became chaotic. Sweet and innocent by nature, Darrel struggled to maintain his grades and pursue an interest in music while changing homes many times, witnessing violence, caring for his younger siblings and suffering abuse at the hands of his surrogate father. Meanwhile, his sibling’s gender transition provoked Darrel to deeply question his own sexual identity.

The fractured narrative of Mamaskatch mirrors Bertha’s attempts to reckon with the trauma and abuse she faced in her own life, and captures an intensely moving portrait of a family of strong personalities, deep ties and the shared history that both binds and haunts them.

Beautifully written, honest and thought-provoking, Mamaskatch―named for the Cree word used as a response to dreams shared―is ultimately an uplifting account of overcoming personal and societal obstacles. In spite of the traumas of Darrel’s childhood, deep and mysterious forces handed down by his mother helped him survive and thrive: her love and strength stayed with him to build the foundation of what would come to be a very fulfilling and adventurous life.

Here is the ending of Darrel’s sad and yet triumphant story of Bertha’s escape from the residential school:

Bertha, Margaret and their aunts managed to make it home late in the evening the day they escaped from St. Bernard’s. Their sister Agnes wasn’t with them. She had been convinced that it was just a matter of time before the police would round them up. As they were walking she reminded her sisters and aunts what happened to students who left and were taken back. Convinced she would die if she went back, she continued walking to the junction of the highway to Edmonton and hitchhiked as far as she could go – to land’s end – the Pacific Ocean.

For weeks Bertha slept in her mother’s bed. Her mother even had to take her into the bushes or outhouse to pee. Margaret was more independent but she didn’t go far on her own either. Whenever a policeman or stranger in a uniform or suit showed up – the girls would hide and not come out until they were called by name. Bertha’s mother registered the two sisters for regular school in Slave Lake. They attended for one year – but the daily trip by dogsled became too much. Bertha taught herself and Margaret to read, write and do arithmetic.

Word spread quickly about the escape. A rumor circulated that the nuns were scared of Bertha’s teen-aged aunts and had them expelled. And there had been so many deaths at the school that local police stopped responding to the church’s requests to arrest and return children.

With the exception of Bertha, the girls married young and raised healthy families. Margaret had eighteen children. Agnes married a fisherman on the coast, worked her whole life in a cannery, and raised one son who became a prominent surgeon.

For some reason, perhaps a series of tragic deaths of her most beloved in rapid succession – compounded with childhood separation from her mother and untold abuse at the hands of nuns and priests, Bertha fell apart in her early thirties – became a chronic alcoholic and abandoned her seven children.

—dg