.

First we go under: a wide-eyed, thrumming, Rosamund Pike stumbles down a ramp into a subway station.

Before the tale even begins, her body is contorted, an arm out to the side like a broken doll, her gaze voracious, expectant and searching. A wounded creature.

The soundtrack features the sound of keys clattering, a jarring noise. She seems under threat before there is even a threat.

When she finds the hovering device in the jaundiced subway, it appears like an answer to her objectless terror. Does the device find her or does she create it to externalize her horror? Enough ambiguity to make one think the subway is wallpapered yellow. Director Ringan Ledwidge says he drew inspiration for the film from two sources: it “merges the menacing ball from Phantasm and the maniacal subway scene from Andrzej Zulawski’s Possession” cites Rolling Stone Magazine. The dance that follows haunts, seems familiar and uncannily unfamiliar. It haunts.

I am haunted, too, by Kaja Silverman and Harun Farocki’s chapter on Jean-Luc Godard’s Vivre Sa Vie, how they note at key moments Godard’s film becomes about the actress, Anna Karina, not the part she is playing. Pike is playing a part here, of course, but it’s impossible to leave her out of it. She exceeds the role. Ledwidge in an interview with Alex Denney in Dazed magazine agrees:

It’s not a role that you would traditionally associate Rosamund with, quite often I think she hasn’t been given the chance to explore herself as an actress. Until recently you might have thought of her in a period movie or something like that, but then she did Gone Girl and you’re like, ‘Holy shit, she’s really capable of some dark stuff.’ So I thought if Rosamund really went for it, and went as balls-out mental as she would need to, she could be a really interesting, really surprising choice.”

The more traditional Pike of period piece films at odds with the disruptive and excessive Pike. The film evokes the first Pike to corrupt her with the second. Her out-of-date moss-green dress, her nylons, her heels, all seem to suggest something is not quite right, like she herself is a little alien here, out of time and place.

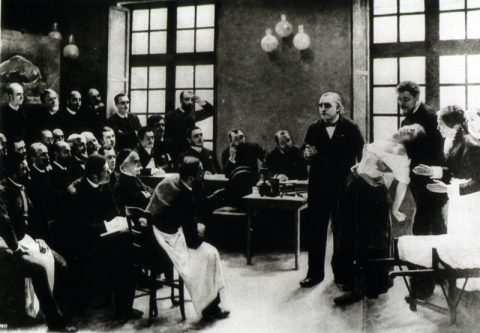

I am haunted, too, by the Salpêtrièr hysterics.

Georges Didi-Huberman summarizes in his Invention of Hysteria: “In the last few decades of the nineteenth century, the Salpêtrière was what it had always been: a kind of feminine inferno, a citta dolorosa confining four thousand incurable or mad women. It was a nightmare in the midst of Paris’s Belle Époque.”

Charcot gained a reputation for his Tuesday lectures. These partly live on in photographs. In his analysis, Didi-Huberman links the hysteric’s body with the doctor:

With Charcot we discover the capacity of the hysterical body, which is, in fact, prodigious, it is prodigious; it surpasses the imagination, surpasses “all hopes,” as they say. Whose imagination? Whose hopes? There’s the rub. What the hysterics of the Salpêtrière could exhibit with their bodies betokens an extraordinary complicity between patients and doctors, a relationship of desires, gazes, and knowledge. This relationship is interrogated here. What remains with us is the series of images of the Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière.”

The hysteric’s contortions then connect doctor and patient, a transference and counter-transference. Drawing back to Pike and Ledwidge, we also see the connection between the director’s camera and Pike’s hysterical performance, possessed, dispossessed and disruptive.

It’s hard not to see the alien device as camera, especially in the manner it seeks to possess and objectify her. Narratively there is no catharsis here, no place where she triumphs over the alien device or is set free. Pike’s body performs for the camera / device as it seeks to possess her, puppet her to extremes of expression, drive her to violence against herself.

Yet I am haunted by Pike, haunted by her laughter and her howls, her body as defiant. As Ledwidge notes,

For an actress you’ve got to be brave, because you’re doing things that are gonna make you look ugly or weird in certain moments, and if you’re not committed it ends up not looking great. But she really nailed it – we built foam tile walls she could slam into, but she was still pretty bruised and exhausted by the end. It was disturbing and scary and sexy all at the same time. You felt like you were seeing something you shouldn’t really be seeing.

Her laughter and howls rupture the puppetry. Maybe it’s something we shouldn’t really be seeing, but she is the voodoo doll and the bokor. Despite the possession, Pike wins.

—R. W. Gray

.

.