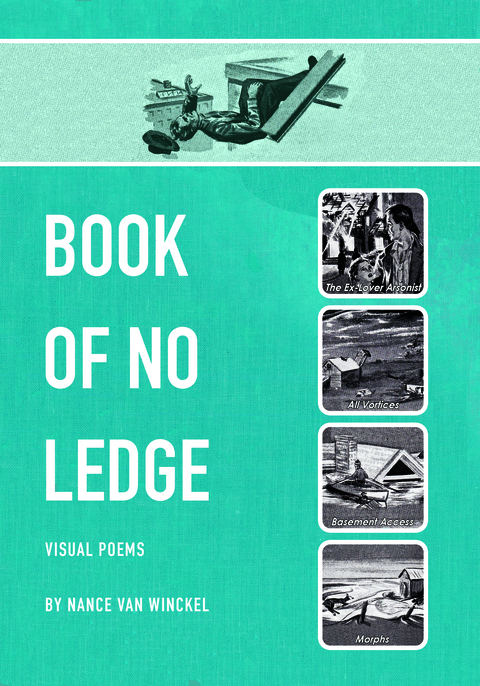

In Book of No Ledge, one of her new collections, poet and writer Nance Van Winckel brings together poetry and visual collage in a series of brilliantly reimagined encyclopedia entries and maps that are a pleasure to read. Witty, both lyrical and satirical, beautiful to look at, and wonderfully inventive, the collection lives up to poet Mary Ruefle’s description of it as “a book of wonder.”

Recently Nance Van Winckel spoke with U.S. poetry editor Susan Aizenberg about Book of No Ledge in a series of emails. Numéro Cinq is thrilled to present here two of the collages from the collection, together with a summary of their conversation, and a third, more recent piece of what the poet calls “wall writing.”

Susan Aizenberg (SA): I love your charming Introductory note, in Book of No Ledge, in which you describe a child first infatuated with a handsome door-to-door encyclopedia salesman, and then in love with the books themselves. Though there was no handsome door-to-door salesman in my experience, I remember feeling as a child a similar fascination with encyclopedias and illustrated guides of various kinds. I’m wondering if you would talk a little about your childhood experiences as a reader as they relate to this book.

Nance Van Winckel (NVW): Well, I was a reader as a kid and I was very interested in the sciences. Because my family moved frequently, I was often the new kid in school, and I read in the lag time it took to make new friends. Books were a “constant” in my life. I liked the diagrams of how things worked— especially bodies and body parts. Early on in life I wanted to be either A.) a spy or B.) a laboratory scientist. And perhaps becoming a writer/poet was a sort of melding of those two professions.

SA: I love the idea of writer/poet as a melding of spy and scientist. I’m particularly drawn to your vivid description, in the intro, of the point of view and voice of the encyclopedia, wonderfully personified as “Mr. Explainer,” and how they change over time as Mr. Explainer realizes the “you” has become a much older woman with “nice sharp scissors and even X-acto blades” – another image I love – who questions his authority. This idea of voice or voices seems important throughout the book, which is rich with wordplay, satirical humor, puns, and seemingly effortless shifts in diction. I’m wondering if you would speak a bit about voice in your work, and how the idea of being in dialogue with Mr. Explainer shaped (if it did) the series of photo-collages.

NVW: Yes, exactly! Talking back to Mr. Explainer from a future quite different from the one he (Commandant of the Past) posited so definitively, so upbeat and full of happy endings—that was very much the tone, which for me is a kind of fuel. I have to get the stance before almost anything else. The attitude. If only as an adult I could again be the imp-kid, the sassy girl, I was when I was ten. That girl got smacked sometimes or sent to her room. I squashed her down. But hey, apparently she ain’t dead yet!

SA: Clearly, and thankfully, she is not! Can we talk a bit about the conception and creation of the book, which seems to me equally a work of literature and visual art? It is, first off, a lovely physical object; the pages are silky (like encyclopedia pages?) and the collages quite beautiful. There is so much to look at and read and consider on every page – I love the richness of it. I don’t think I can overstate what a genuine pleasure it is to read. Would you talk a bit about your process?

NVW: I worked on these pages over the course of about five years. The encyclopedia I altered is actually 13 volumes, and at about a sixth grade level. As I paged through it, it brought back those memories from girlhood and reading, and I fell back in love with all the graphic elements. So I mainly used pages that had a lot of visual material on them. My method was to work on these very “visual” pages, which were all in black and white, and part of what I was doing was teaching myself—as I most always am these days—new techniques in colorizing, cut-and-paste, and many other things available from my old friend, Photoshop. (I’ve been noodling around with that program since back when I was a magazine editor [of Willow Springs] and designing the magazine with a program called PageMaker, which evolved into Photoshop.) As I worked on the visual layout of a page, I would often write new text to replace the old text. Sometimes I just carried printouts of the pages around with me in their waiting-for-text states, i.e. big blocks of space where text would go. I liked this method because I could work on other projects simultaneously—linked stories, other “regular” poems, etc.—and these encyclopedia pages would wait patiently for me and, as I mentioned above, I sort of knew the persona to slip into when I returned to them.

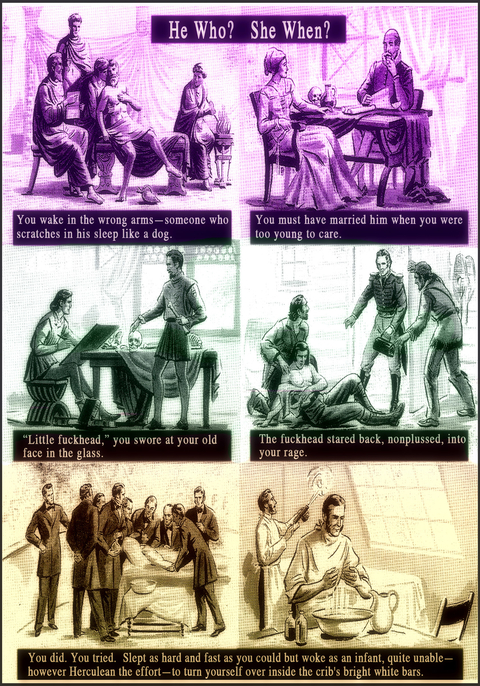

SA: You’ve generously shared with us two of the pieces from the collection. Would you speak a little about them?

NVW: One of the aspects I’m drawn to in this work is how the visual material can interact with the text—fill in gaps in the “story,” provoke a nonlinear kind of logic, or suggest a larger worldview/context than the text alone permits. This page, now titled “He Who? She When?”, was originally called “Advancements in Medicine.” I don’t feel in any way obliged to stick with the original subject matter of a page. For me, it’s all about the interplay of words with images that have “tangential” connections, thread-like, or tonal. The sense the pieces make, I hope, is more intuitive than conscious and rationale.

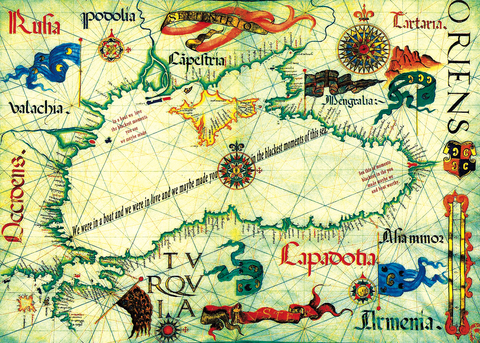

I haven’t said anything about the maps, and I’d like to. Most of these were not part of the encyclopedia I altered. Rather, they were from an online website (from New York Public Library’s “digital collection”) of public domain “rare” maps. I used these in the book a little like section dividers, and I am forever grateful to Pleiades Press for allowing them to be double-page spreads and displayed so well. (I’m grateful to Pleiades for so much! The support of the editors and designers there has been extremely helpful to me.) Here, my little bit of text—”We were in a boat and we were in love and we maybe made you in the blackest moments of this sea”—is spread out upon a map of The Black Sea, a place I’ve actually been. The text is stamped around into the sea with all sorts of variations on the arrangement of these words. This felt like a kind of homage to ancestry, not just mine but “ours.”

SA: Thanks so much, Nance! Can we end with you sharing with our readers what you’re working on now?

NVW: Yes, my eighth book, Our Foreigner, received the Pacific Coast Poetry Award and is just out from Beyond Baroque Books. I’m working on a book that’s primarily a memoir; it has many sorts of hybrid forms going on in it, including some visual black and white collages.

And I continue to do a little wall-writing. This is a recent piece.

I have a website for examples of this work.

Nance Van Winckel is the author of eight books of poetry, most recently Our Foreigner, winner of the Pacific Coast Poetry Series Prize (Beyond Baroque Press, 2017), Book of No Ledge (Pleiades Press Visual Poetry Series, 2016), and Pacific Walkers (U. of Washington Press, 2014). She’s also published five books of fiction, including Ever Yrs, a novel in the form of a scrapbook (Twisted Road Publications, 2014) and Boneland: Linked Stories (U. of Oklahoma Press, 2013). She is on the faculties of Eastern Washington University’s Inland Northwest Center for Writers and Vermont College of Fine Arts’ MFA in Writing Program. The recipient of two NEA poetry fellowships, the Paterson Fiction Prize, Poetry Society of America’s Gordon Barber Poetry Award, a Christopher Isherwood Fiction Fellowship, and three Pushcart Prizes, Nance lives with her husband Rik Nelson in Spokane, Washington.

Susan Aizenberg is the author of three poetry collections: Quiet City (BkMk Press 2015); Muse (Crab Orchard Poetry Series 2002); and Peru in Take Three: 2/AGNI New Poets Series (Graywolf Press 1997) and co-editor with Erin Belieu of The Extraordinary Tide: New Poetry by American Women (Columbia University Press 2001). Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in many journals, among them The North American Review, Ted Kooser’s American Life in Poetry, Prairie Schooner, Blackbird, Connotation Press, Spillway, The Journal, Midwest Quarterly Review, Hunger Mountain, Alaska Quarterly Review, and the Philadelphia Inquirer and have been reprinted and are forthcoming in several anthologies, including Ley Lines (Wilfrid Laurier UP) and Wild and Whirling Words: A Poetic Conversation (Etruscan). Her awards include a Crab Orchard Poetry Series Award, the Nebraska Book Award for Poetry and Virginia Commonwealth University’s Levis Prize for Muse, a Distinguished Artist Fellowship from the Nebraska Arts Council, the Mari Sandoz Award from the Nebraska Library Association, and a Glenna Luschei Prairie Schooner award.