When the Rawlses finally arrived at Grandma and Granddaddy’s house in Eufala, there was no place to park. Cars crowded the lawn and driveway, and TV vans lined the shoulders of the road, leaning out from the pavement as if feeling poorly and ready to topple over and give up the ghost. (“The ghost,” the boy whispered. Was it bad? Bad to say words aloud as you thought them?) So Dad left the pickup down the block by a house with a tree where a farmer in overalls was hanged by the neck until dead. Spooky, since it was already getting dark.

Jordan had been taking pictures of the sunset with Mom’s iPad as they headed south from Muskogee, and he knew it was “unworthy,” the word she had used—“unworthy of you to keep harping on it on such a day”—but the thought came to him, There’s still time. (“Time,” he said.) Time for trick-or-treating, he meant.

Dad carried Su Ellen, asleep in her car seat and tented in a pink blanket, and Mom brought what Dad called the “superfluous bucket of chicken.” “I know my people,” he’d said, but she insisted you couldn’t show up empty-handed. The boy followed, his school backpack slung over one shoulder. Dad buzzed his own head every Sunday morning, except for a curl from his widow’s peak, and you could see a port wine birthmark as big as a pancake on the back of his scalp. Mom’s hair was frizzy and dark, and she had a slight overbite and a zit at the corner of her mouth which she had daubed with makeup.

At Grandma and Granddaddy’s yellow home on the corner, its American flag at half-staff, they’d forgotten to string up the spooky orange lights this year, but their neighbor’s house had an inflatable witch, a huge spider clinging to the eaves, a dummy holding a jack-o’-lantern head, and fake tombstones for IZZY DEAD and IMA GONER and BARRY A. LIVE.

“I hate Halloween,” Dad said.

Reporters were waiting on Grandma and Granddaddy’s lawn. Their cameras and microphones were labeled with ABC, CBS, Fox, and others, too, but some of them just had notebooks and recorders. Noticing Jordan’s family—the Chicago Rawlses—they stopped checking their smart phones. Dad, usually surefooted and long of stride, slowed, as if considering whether to retreat and find another way in. When the Rawlses reached the yard, the reporters huddled around with faces arranged so sad, Jordan wondered if they, too, had known Uncle Aaron. A lady in hoop earrings said, “Excuse me, but are you all family?”

Dad said, “I’m his brother. Was.”

“I am so sorry. I can only imagine.”

The reporters all nodded. They, too, could only imagine.

Dad looked at the house as if hoping his folks might come out and rescue him, but nobody stirred in the house. A cameraman had him state and spell his name for the record. Dad handed the car seat with baby Su Ellen to Mom and she stepped aside. He was wearing civvies, but the reporters must have guessed from his haircut, because someone asked for his rank (“Captain”), then said, “Navy?” and he told them, “United States Marine Corps.” The reporters wanted to know how Dad felt. He said it was a living nightmare. The NBC lady asked how long Aaron had been a soldier, and Dad corrected her: Marine, ma’am. Not soldier. When someone asked if there was a wife, he said no, just the ex, she’d be flying in tonight. No; no kids.

One reporter wanted to know what Aaron was like as a kid. Well, sir, Dad said, clearing his throat, my brother, he was always getting up on top of things. He gritted his teeth and for a moment Jordan thought his father was grinning.

The FOX lady asked, “Like, for instance?” Oh, Dad told them. Like when Aaron was three and he clambered up onto the carport roof. Yes, ma’am, three years old. Little monkey. Dad was seven, followed him up to make sure he didn’t fall off. A neighbor phoned their mom, is how she found out. Nine years old, Aaron hauled his bike up on top of their father’s tractor-trailer rig and rode off the end, pretending to be Evel Knievel. Broke a bunch of bones.

“He was my kid brother,” Dad said, “but he was my hero. Nothing scared him.”

Mom slipped a tissue in the hand at his side. He dabbed his eyes and nose, apologized. The reporters said of course, no need. A CBS lady touched his arm.

Just then Jordan’s backpack slipped off his shoulder and spilled open. He’d forgotten to zip it. Out tumbled the Wimpy Kid books and his Evil Gesture costume, which Mom had packed for him. The Evil Gesture wore a three-horned hat and a suit of a red and black check pattern, with tiny skulls instead of bells hanging from the zigzag collar. But what everyone was looking at was the cackling skull mask. Jordan was too horrified to move. Mom’s face changed from sad and weepy to really, really angry, and she crammed everything back in and zipped up the backpack. Jordan was hot with shame. His grandparents were not supposed to see the mask, today of all days, and here it was, revealed for TV.

A gray-haired reporter said, “You fixing to trick-or-treat, son?” Jordan didn’t answer, afraid this man, too, would find him unworthy. The reporter said, “Well, that’s a pretty spooky costume.”

Somebody asked if you had one message for the American people today, what would it be? Dad said he did not feel called to advise the nation right now. He added, “Excuse us,” and led the family into Grandma and Granddaddy’s side door, where a sign read, NO MEDIA!!!

The kitchen was over-warm even though a window was open, and a biscuity, hot-doggy smell filled the air. People at the counter were chopping carrots and distributing ice in red plastic cups. The Grands, as Mom called Grandma and Granddaddy, were nowhere to be seen, but Jordan recognized their pastor from the Free Will Baptist Church and Dad’s cousins and uncle of the Tulsa Rawlses. Across the room, Aunt Staci, Dad’s big sis, was listening to a marine staff sergeant in dress blues who was shaping an invisible lump of clay with his hands as he spoke. Aunt Staci was an army nurse but wore civvies today like Dad. Uncle Dave, her husband, a doctor, was deployed to Afghanistan.

With a glance that told Dad, “You were right,” Mom set the bucket of chicken on a sideboard already crowded with a crockpot of gumbo and a pan of ribs and fried chicken and mini-hot dogs and biscuits and salad and corn with specks of something red like peppers in it, as well as brownies and cookies and cake. Su Ellen began crying, and Dad removed her from her car seat and tucked her in a baby carrier on his chest. Babe-zers blinked in bobble-headed astonishment. Were there dis many people on Earf? Where dey come from? Babies were so funny if you scrutinized them. Aunt Staci, puffy-eyed, pinching her nose in a much abused tissue, rushed over and hugged Mom and Jordan, then captured Dad and Su Ellen in a baby sandwich. People turned ugly when they cried.

“I just can’t get it out of my head,” Aunt Staci said.

“You didn’t watch the video!?”

“Oh, God, how could I miss it? It just was on in the Emergency Department. I mean, not all of it, but enough.”

“Where’re the folks?” Dad said.

Aunt Staci led them to Dad and Uncle Aaron’s old bedroom, where Jordan and his parents always slept when they visited. She knocked and peeked in.

In a room lighted by the afterglow of the sunset, a very large couple had pulled up tiny chairs beside a bed on which a skinny, white-haired lady lay facing the wall. Jordan knew them—the Reiersgords, Grandma and Granddaddy’s best friends from church. He was a throat-bearded man whose belly bulged in his orange OSU Cowboys jersey. His wife was a frog-shaped lady who seemed to have slipped rubber bands around her wrists, elbows, ankles, and neck. The white-haired lady rolled over on the bed to squint at them, and with a shock Jordan recognized Grandma. She’d always been roly-poly and pink-cheeked, but she had wasted terribly skinny, and her jet hair had gone white since he had last seen her on the Fourth of July. She was part Choctaw (“though not enough to do me any good”), and her Indian features were pallid, even bluish.

“OH!” she cried, her eyes seizing Jordan. “Come here, you!” Her face wrinkled up, and she swung her legs off the bed as she sat up to hug him, smearing his skin with her wet, whiskery cheek. “What took you all so long? I was so worried about this guy.” The ferocity of Grandma’s embrace alarmed the boy.

Mom and Dad sat down on either side of her and hugged her sidelong, and the grownups all cried. Mrs. Reiersgord said, “We’ll be getting back to the kitchen.” She nudged her husband, who lumbered out after her, supporting his belly as if it might otherwise sag down around his ankles.

Jordan felt bad, as evil as an Evil Gesture, but when he thought of Uncle Aaron, he couldn’t cry, because he didn’t feel sad, only afraid. He’d been sick to his stomach ever since he first learned about Uncle Aaron’s kidnapping in Tajikistan last May. He would ask Mom to drive him to school, and she’d say, “Since when do you need a ride?” All the way there he was alert for kidnappers and would notice whenever a passing car or UPS van slowed down, possibly to grab him. The boy barely remembered his uncle, whom he had only seen twice in the last three years, and in his mind, the strong, shaven face of Aaron in his Officer Service Uniform had been replaced by that of the gaunt, bearded man in orange, kneeling before some kind of Ninja in black. The boy did remember his uncle tickling him once on the floor of the den as he screamed for mercy. Jordan had kept a wary distance after that.

Last spring Uncle Aaron had mailed a Kyrgyz felt hat, as tall as a pope hat, that he had found in a market. He addressed the gift to “The Chicago Rawlses,” but Dad decided it was for Jordan. Mom thought it would make a great Halloween costume. Hearing this, the boy made a point pushing it off the back of the dresser in his closet, to be forgotten amid the dust on the floor. After Uncle Aaron was kidnapped, he felt guilty, though not enough to put on a stupid hat like a Smurf might wear and regular old clothes and call it a costume, which is the kind of lame-o idea grownups came up with. Luckily, Mom had forgotten the hat.

These past months Jordan had been more anxious for his father than for the remote uncle of legend. “Are they going to try to kidnap you, too, Dad?” “Buddy, they wouldn’t dare. Besides, the bad guys are way far away.” Still, Dad had bought a Colt M45 Close Quarters Battle Pistol and began taking Jordan to the shooting range on weekends. At night boy armed himself with his Nerf gun in bed, and this upset Mom when she sat on it while tucking him in, because she thought he was playing with it after lights out. Actually, it was for protection. He was not a moron, he didn’t think a Nerf bullet would kill a Tajik, but if it hit him in the eye, it would give Dad time to come running with his gun.

Last night Jordan had awakened to find himself in the back seat of the pickup. Out in the darkness a billboard glided past with a smiling lady’s face and the words FREEDOM FROM PAIN. Headlights came at them and taillights streaked away. Su Ellen was asleep in her back-facing car seat beside him. Oddly, Mom was at the wheel. Dad slumped in the front passenger seat, his head bobbling forward and righting itself.

“Where we going?” Jordan said. (“Going,” he whispered.)

“Shhh, let Daddy sleep. Grandma and Granddaddy Rawls’s.”

“What about Halloween?” he said.

“You can trick or treat there.”

The next time he woke, it was daylight and Dad was driving. They were pulling in to a McDonald’s. The boy asked where they were. “Springfield,” said Dad. “Abe Lincoln’s old stomping ground.” It wasn’t until they finished their pancakes and sausage that Dad said, “Buddy, we got some bad news.”

§

Now Grandma released Jordan. As she pulled her palms down her face, stretched her saggy skin.

Jordan said, “I’m very sorry about Uncle Aaron, Grandma.” (“Sorry,” he whispered.) He glanced at his mother, who nodded that this was the right thing to say. Grandma peered at the boy’s face, but not finding something she sought, she lay back down facing the wall. She kept a hand on her tummy. Maybe she was hungry.

“Grandma, I’ll share my candy with you after I go trick-or-treating.”

Mom swatted his shoulder and bugged her eyes angrily at him. What? he mouthed, and she nearly swatted him again.

Dad said, “Your ulcer acting up, Ma?”

Grandma shifted in a lying shrug. Aunt Staci nodded for her.

“Maybe you ought to see a doctor,” Dad said.

Grandma pulled a pillow over her head. “OHHHHH, stop it! All of you.” Jordan’s spine shivered all the way to his tailbone. The grownups looked like they didn’t know what to do.

For a while they sat there stroking Grandma’s shoulder and leg. She reached back, but when Dad took her hand, she pushed it away and found Jordan’s instead. What should he do? Just stand there holding his grandmother’s soft, boney hand? Mom nodded: Just like that. He surveyed the room. Grandma’s treadmill stood along one wall, stacked with boxes. A bookshelf was lined with Uncle Aaron’s old collection of toy Indian warriors and cavalrymen in blue, made of tin and painted. One of the soldiers had long, yellow hair like Custer. He was threatening to saber a brave in full-body black war paint who brandished a tomahawk.

“Kirsten’s in the living room with your granddad,” Aunt Staci told Jordan. (Kirsten was Jordan’s cousin.) “Maybe you two should go say hi. Your Mom and I can set with Grandma.”

They found Granddaddy watching Fox News with Kirsten. Who had pink hair! They both stood up for hugs. She was wearing jeans and pink socks and a pink hoodie that read MIZZOU, which is where she played mellophone in the marching band. Granddaddy had the same old circus barker’s mustache and goatee, and his bald, spotty head sprouted stray hairs, shimmery against the light. After hugs Granddaddy said, “He’s with the Lord now,” and Dad said, “He sure is.” The left side of Granddaddy’s face kept flinching into a half mask, baring his teeth and flexing the tendons of his neck, as if a malevolent lightning bolt had illuminated a painting in the Disney World Haunted Mansion. A tissue box lay by Granddaddy’s chair, and they wiped their cheeks and honked their noses and talked about Grandma. Ought to see a doctor for sure, but try telling her that.

Kirsten nudged Jordan with her hip, throwing him off-balance. “Look at this big guy! We’re going to have another linebacker here, just like Luke.” Luke was her brother, but he didn’t play football anymore because he was studying for his master’s in England.

“Jordan’s playing Pop Warner,” Dad said. “Offensive tackle.”

“I lost a tooth,” the boy said. He opened wide to show his cousin the hole in his gum.

“Last week, middle linebacker knocks him flat,” Dad says. “Hits the turf so hard, he spits out a tooth, Jordan. So he finds it and runs off the field and hands it to Mom. Didn’t want to miss out on that dollar.”

“Whoa!” Kirsten said. “You stud!”

In fact, Jordan wasn’t very good at football. His size had excited the coaches at first, but he was clumsy and was frequently humiliated by smaller opponents who wriggled past to sack the quarterback or take the running back down for a loss. His team had lost every game but one. In the car home Dad always advised him on everything he had done wrong. “You cost your team twenty yards holding.” His head coach told him the same thing, at the top of his lungs.

Kirsten was chewing her hair, which was so bright it did look eatable, like cotton candy. The boy’s fingers reached out and combed her pink locks. “What are you going as?” he said.

At first she didn’t understand; then she giggled. “Jordan, this isn’t a costume. It’s my normal hair. I dyed it.” To Dad she said, “He is so funny!” But maybe she decided smiling was unworthy, because her face fell and she tucked the hair back in her mouth.

Granddaddy said, “Sit down, take a load off your mind.”

He bent at the waist and at the knees and groped back for the armrests and tottered back into the easy chair. He pulled a lever to clump up the footrest. “Little woozy with the meds they got me on.” Kirsten sat in the rocker and held his hand. A couch was aligned with its back to the dining room and the kitchen beyond, and Jordan sat beside Dad and Su Ellen and was enveloped in her aroma of talcum, pee, and milky barf.

“So how was the trip down?” Granddaddy asked the TV. “Y’all get out before that ice storm? They showed it on the weather.”

“Dodged the worst of it.” Dad lifted his hands from his knees and let them fall. “Little sleet is all.”

“Well, that’s—.” The spasm seized Granddaddy’s face again. He raised his Crimson Tide coffee mug to his lips and peered in, then set it down.

Dad asked what they were going to do about “arrangements,” since they didn’t have a—. But he did not finish his sentence.

“Seeing as how the government wouldn’t let us come up with the ransom, maybe they’ll let us purchase his REMAINS!” Granddaddy cried. “You heard, right? The terrorists are offering to sell us his body. Maybe they’ll give us a discount on the head.”

Glancing at Jordan, Dad said, “Dad, he doesn’t know how it happened.”

A commercial came on for a man who owned a fleet of red plumbing vans and a herd of cattle and was promising to stand up for Oklahoma values.

Kirsten said, “Can I?” and took the baby from the carrier on Dad’s chest and went back to her rocker. When Kirsten stood Su Ellen on her knees, Babe-zers made a face like, Pink hair! As if! You could see how every little thing amazed her.

Dad took his father’s hand. Granddaddy glanced at the hand that was holding his, patted it, looked back at the TV. Dad let go and picked up the remote. “Mind if we turn that off?”

Granddaddy gestured at the table with a gnarled finger. “You put that dang thing down.”

“Yes, sir.”

A blond lady with big eyelashes told the news about the USA. Oklahoma was red and Illinois was blue. So were most other states, boldly the one or the other, excepting a handful that were pinkish and blueish or gray, neither hot nor cold, as if they might be spewed from the mouth of God. Jordan jiggled his knees. Dad stopped him with a hand on his thigh. “I was just telling those reporters how he got up on the roof.”

“I remember that,” Granddaddy said.

Now it was that TUMS commercial where a headless chicken slaps up a man at a barbecue. Then the man fights back, and the chicken respects this, so they become friends and play volleyball.

The boy went over to peek out the curtains. Darkness seeped up from the black forms of the journalists and the TV vans and through the veiny trees and across the sky. Jordan slipped a wooden rod into the sliding glass window to lock it. Down the street a car stopped and let out three kids, hard to say what, maybe a Zombie, a Princess, and a Batman. They skimpered up to a double-wide trailer. Dad patted the seat beside him, and Jordan came back and plopped into the deep of the couch.

“When are we going trick-or-treating?” Jordan said.

Dad shushed him with a look of fury.

On the screen beside the news lady, a photo of Uncle Aaron appeared. He was wearing a beard and a shirt like the Oklahoma State Cowboys when in fact he’d been a Sooner. A Ninja was standing beside him with a knife. “2nd Lt. Aaron Rawls” was printed on the frame. Across the top of the screen it read, NO MERCY.

“Leave the room!” Dad said. “Now!”

“Why can’t I watch?”

“GET out of here, or I’ll burn that costume in the fireplace.”

The boy fled to the kitchen, squeezing past Mr. Reiersgord, who was watching the TV from the doorway. Mrs. Reiersgord put mitts on her rubber-banded hands and opened the oven door. Hammy steam gusted out. “Stand back, Aar—Jordy. What am I saying?” (“Air,” the boy whispered. He was not air, was not Air Jordans, was also not Aaron. Plus he hated the name Jordy.) Over at the sideboard he snitched a finger lick of frosting off the cake. From the doorway Mr. Reiersgord hollered, “Statement from the White House!”

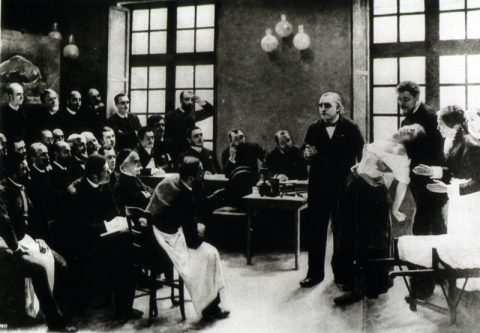

Jordan sneaked back in with everyone stampeding from the kitchen. The TV screen was split, showing the news lady and an empty podium with two flags behind it, American and a blue one with stars. Kirsten vacated the rocker, handed Su Ellen back to Dad, and sat on the floor at Granddaddy’s slippered feet. People laid hands on Dad and Granddaddy as if for a calling upon of the Holy Ghost. Rubber-banded hands, as heavy as fat little haunted house gremlins, landed on his shoulders from behind. Obama came onstage and said, “Good evening, everybody.” He gestured a fist with his thumb sticking out and said something about Aaron Rawls. He was mad. At Uncle Aaron? Turned out the president, too, could only imagine. He said the entire world was appalled, and the people who did this were not Islam. But we would confront this hateful terrorism and replace it with hope and civility. When he was done, reporters asked questions. The president said it would be premature to speculate, but make no mistake. He walked off, and the air seeped from the lips of the watchers here, as if they’d been expecting something else, though just what, nobody said.

What Jordan was not clear on was, was anybody going to revengence the Tajiks and Ninjas? But he did not ask, because everyone was crying again except for him. Granddaddy’s whole face was frozen in his evil mask, his eyes red. Dad came over and half-crouched to hug Granddaddy, his cheeks shellacked with tears, resting his chin on his father’s bald pate.

Now the TV showed the blond lady at her desk, they’d be right back. An X-ray of a skeleton danced in high heels. The watchers began filtering back to the kitchen, and Mrs. Reiersgord’s hands departed from Jordan’s shoulders. The skeleton flapped its arms and wriggled its hips. It turned into a lady with gray hair. She was smiling.

Granddaddy said, “You note how he always tries to explain away the religion. How stupid does he take us for?”

“Dad, he’s just making the point that not all—”

“So who should we blame, then? Mormons?”

The front doorbell rang and Jordan cried, “I’ll get it!” Out on the dark porch were the trick-or-treaters he’d seen earlier, the Zombie and Ballerina and a Darth Maul, it turned out, not Batman, wearing a rubber mask with its red and black devil’s face and baby goat horns.

“Kirsten, we got any candy?” Jordan called.

She palmed her brow. “Oh, jeez, did we forget candy?”

In the street behind the kids, two dark heads were watching from the car. Jordan ran to the kitchen and hollered, “We got any candy?”

“Not before dinner,” said Mom.

“Not for me!” Jordan cried in vexation. “There’s trick-or-treaters!”

But she was talking to the preacher, and she raised a finger. That’s one! Jordan checked Aaron’s room, but Grandma was gone. Upon his return, the living room door was a kidless rectangle of dark. Anyone could have infiltrated the house. He shut the door and hung the security chain.

Su Ellen was crying, as purple-faced as Coach Barker after a fumble. A poopy smell wafted. “You’re right, Pop,” Dad said in a tone that suggested he did not wish to argue, and he added, “Sorry, we got a situation here.” He headed for the hallway. By now, everyone had cleared out of the living room except for the staff sergeant, Jordan, and Granddaddy.

“So who do you think they were, Aaron?” Granddaddy asked Jordan. “Presbyterians? Buddhists? Maybe your grandmother should’ve dressed up for that press conference in orange lama-lama robes instead of that danged headscarf.”

The boy’s skin prickled all over. “My name’s Jordan, Granddaddy.”

The staff sergeant’s face blanked as the gravity of the error sank in.

“Well, I know that!” Granddaddy said.

“But you said—.” Jordan bethought himself. His mother always urged him to do this, to bethink. “I have to go.”

He was waiting in the hall as his father emerged from the washroom with Su Ellen, who was still crying, though at a lower volume.

Very respectfully the boy said, “Dad, may we please go trick-or-treating now?”

Dad gritted his teeth. “Jordan, did you not just see what—?” Then he paused, bethought. He said more calmly, “I need to be here for Grandma and Granddaddy. We haven’t even eaten dinner. Be patient. What did I say?”

“Seven o’clock.”

“Maybe, after seven-thirty, is what I think I said, if there’s an opportunity. We’ve got plenty of sweets here, anyway. Did you see those M&M cookies?”

Jordan had.

“Come on, they’re calling us.”

Mr. Reiersgord and several church friends who had been helping prepare dinner had departed, leaving his wife, the preacher, and the staff sergeant as the sole remaining non-relatives. Mom took Su Ellen off to feed her. Dinner was ready, but Grandma, Granddaddy, and Aunt Staci were unaccounted for. Mrs. Reiersgord went to round them up but she returned with Granddaddy alone. She said, “Charlotte won’t be eating. Staci’s with her.” She told Dad, “She’s back in their bedroom, so whenever you all want to move your stuff in—.”

Everyone huddled around Dad and Granddaddy and bowed their heads. The preacher beseeched Almighty God to come in this time of grief and bless this family. And bless Aaron, Lord, up there with you, and, and Holy One, thank him for defending our freedom, God, for greater love hath no man than to lay down his life. This drew “amens” from the crowd. Everyone loaded up paper plates at the sideboard and sat in the dining room. Mrs. Reiersgord circled the room, distributing napkins to those who’d forgotten and topping off water, coffee, 7-Up, and Coke. Finally she plopped down, fanning herself, and said, “Whew!” Nobody talked much except for murmured requests for the salt or the butter. Granddaddy broke apart two mini-hot dogs with his knife and fork, eating the crusts separately from the wieners, his face flinching to a mask and then softening. He cleared his plate and headed to his and Grandma’s bedroom. Aunt Staci returned in his place.

Jordan nibbled at a drumstick. Using the green beans as fencing, he created a hog wallow for a farrow of red-speckled corn. He hoped that this evidence of activity on his plate would substitute for the actual consumption of veggies, but when he said, “May I please be excused?” Mom replied, “Not until you clean up your veggies.” Dad told her, “Leslie, forget it. Not tonight.” On the wall Jordan noticed a clock. Eight thirty-six! No, seven thirty-six. But still. Dad saw where he was looking and misdirected: “You can play on the iPad,” even though Jordan had already used up his gaming time.

He played Terraria in the kitchen until the clock over the cup rack showed eight-o-six. He returned to the dining room and stalked around the table twice, then whispered in his father’s obscene earhole, “May we please go trick-or-treating?” drawing an eyeball rebuke.

A strategic withdrawal was required. The boy retreated to Dad and Uncle Aaron’s old room, cutting a cake-slice of light in the darkness as he opened the door. Should he enter? He should. He closed the door but for a crack. Maybe he’d hide here until the grownups noticed he was gone and panicked, thinking he’d been kidnapped. Couldn’t you have taken the child trick-or-treating? That was all he wanted, and we had to make him feel bad about it. As Jordan’s eyes adjusted, they took in the shadowy figures of the toy cavalry and Indians on the bookshelf. Had Aaron worried about Mormon Islams as a kid? A Sioux warrior’s arrow poisoned with horridness shot through his chest.

ACCEPT PAIN, INFLICT VICTORY: this was his football coach’s motto. It was on the team T-shirt. But “accept” sounded wrong, because pain came barreling in, accept it or not, like an illegal clip from behind that took you down. What about fear? Should you accept it, or was it better to resist? And how did you uninflict fear when it flicked you? Jordan closed the door the rest of the way and was enveloped in darkness. Was he afraid?

No. Yes.

The glow beneath the door starkly planed across the carpet shag. As his eyes adjusted, he scowled in the mirrored closet door, but the effect was comical. No tears came, just silly-putty terror.

Only the Evil Gesture could scare off the Ninjas.

The boy pulled his costume from his backpack. He put it on over his clothes, the sleeves and pant legs bunching up uncomfortably. Without the cackling skull mask, he was just a plain old kid, fattened by the extra layer of clothes. Did he dare put on the mask?

He did.

Evil Lord Gesture darkly surveilled himself in the mirror. The transformation encouraged him. Ninjas would panic at the sight of his cackling skull face. And poop in their pants!

Pardon our stinkiness, Lord Gesture, they’d say. We bow to your submission.

Verily, thou shalt die anyhow, says the Gesture. In revengence for Uncle Aaron.

NOOOOOOOOOO, we don’t wanna die!

The Evil Gesture revenges the Ninjas with his diamond Minecraft sword. And they poof into clouds of vile black dust.

The Gesture reached his dread hands for the tin soldiers. Which one would be the bad guy? Custer, of course. Jordan felt around in the dark to figure out which toy was which. The Indian with the tomahawk toddled over and hacked at Custer’s neck. Yah! De-headed. (“De-headed,” he whispered in his mask.) Custer’s body fell over and died. With his fingers the boy tried to break Custer’s head off, pressuring it this way and that, but the solid metal would not budge.

Something moved on the bed and Jordan nearly peed his pants. A dark form lay there, staring at him. Grandma. He yanked his mask off, taking with it his hat. Hadn’t Mrs. Reiersgord said she’d gone back to their room?

Grandma said, “What’re you supposed to be?”

Jordan told her. (“Gesture,” he repeated in a whisper.)

“An Evil Jester?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“What happened to the one you wore last year?”

This puzzled him, because they had not been here last Halloween. Maybe Mom had sent photos of him in his Spider-Man costume. “I outgrew it.”

“Oh, come on. I could have altered it.”

Jordan did not know what to say.

“Nothing scares you,” Grandma said.

“What?”

“Boys,” she told him. “That’s your downfall. Right off the top of the semi.”

Jordan eased toward the door. “Want me to get Granddaddy?”

When no answer came, he left, shutting the door behind him.

Back in the kitchen, the boy hid the mask behind the refrigerator. He left the lights off. (“Downfall,” he said.) In his array of costume, he evilly manifested himself at the counter, within sight of Dad at the dining room table. But Dad was looking the other way, at Aunt Staci, as she told about the time a couple years back when Aaron met up with Uncle Dave, who was passing through Kyrgyzstan on his way to Afghanistan. At a roadside market two Kyrgyz women got in a fight, pulling hair and knocking over a watermelon cart. Aaron tried to separate them, so they started punching him and whacking him with bunches of carrots. Aunt Staci wiped her eyes and said Aaron laughed very hard about that and loved to tell the story afterwards. Kind of like Afghanistan and Iraq, he said. Turns out they’d rather be let alone to fight each other, didn’t want to be rescued by us.

Jordan’s eyes returned to the iPad, but all he did was whirl it on the smooth countertop. Twirl, thwup, whup, whup.

The kitchen light flipped on. Jordan did not look up.

Dad said, “How come you’re sitting here in the dark?”

Twirl, thwup, whup, whup.

“Trying to make your mean, old father feel guilty for not taking you trick-or—?”

Thwup, whup, whup.

“I’m sorry, I just find it hard to believe that you don’t care what happened to your uncle. This horrible, horrible—. And yet you—.”

Twirl.

“The old silent treatment.”

Thwup, whup, whup.

Dad said, “They cut his head off, Jordan.”

He looked sickened at his own words, as if he wanted to take them back. A horrid feeling pierced Jordan, the poison arrow, and his skin prickled.

“I know,” he said.

“I shouldn’t’ve told—. You know? How?”

Jordan interrupted, “I never said you were mean.”

“All right. All right. Get your mask.”

Jordan reached behind the fridge for the cackling skull face. It was bearded with greasy dust. Dad brushed it off over the trash can and washed it in the sink.

“How come you stuck it back there?”

“You said Grandma and Granddaddy shouldn’t see it.”

Dad considered this. He dried the mask with paper towels.

They slipped out the back door and cut through the neighbor’s yard to Third Street, where Granddaddy had parked so he could come and go without encountering reporters. Granddaddy had told them that there was a “Trunk-or-Treat” at the church, where the grownups dressed in costumes and distributed candy from their cars. (“Trunk,” Jordan breathed.) Youth group buses came from forty miles around. This one doctor, he always went as Frankenstein’s Monster. That’s where they headed, the Free Will Baptist Church, Dad up front, Jordan in back.

Thus it was always so with grownups, the Evil One thought as he buckled the seatbelt around his coat-fattened tummy.

But the tables would be turned in the Trunk-or-Treat, when he manifested himself in his dark power, scaring everyone pantsless.

Dr. Frankenstein, look! Ninjas would cry. The Evil Gesture is here!

Impossible! Frankenstein answered. He lives in Chicago.

It’s true, Mine Hair! Run! He’ll poof us into dust devils of black powder.

There can be no outrunning our doom.

But when they got to the Free Will Baptist Church, the lights were out and the parking lot was empty. No cars, no Trunk-or-Treat, no Doctor Frankenstein. Both Chicago Rawlses, father and son, peeked in the dark windows of the Fellowship Hall, where three headless half-men hung from a wheeled coat rack. “Nichts,” Dad said. Granddaddy had told them the Methodists and the Mission Outreach Full Gospel Church had started copycat Trunk-or-Treats, and Dad circled by, but they, too, were abandoned.

“Jeez, it’s barely eight-thirty,” Dad said. “I can’t believe they roll up the sidewalks so early.”

Jordan took off his mask. The skin of his under-face was cold. “I told you!” he said. “We waited too long, and we missed Halloween!” And although he tried not to, in his unworthiest act in a day of unworthiness, he started to weep, not for his uncle, or for deheadings and incivility and Ninjas, but for the candy he was missing out on. He was embarrassed by his own greed and childishness, but he could not hold back his tears. “I thought Halloween would be fun, but it’s not. That doesn’t mean I don’t care about Uncle Aaron. You think I don’t, but I do.” (“But I do.”)

Dad did not scoff, as he did when Jordan cried in football, or lose his temper and shout, as he was known to do, but slumped a little at the wheel. “Look, Aaron. Jordan! Jeez, my brain.” He reached back and, his cold, hairy hand groped blindly to clasp Jordan’s. Presently Dad withdrew the boom of his arm and wiped his eyes. He found a pair of gloves in his coat pocket and inhabited them with his hands. “Why don’t we—?” he said. “Your Aunt Staci and me, we used to take Uncle Aaron out. And—.” He shook his head at some memory.

“And what?”

“And there weren’t Trunk-or-Treats back then. We’d go house-to-house, like in Chicago. Aaron, this one year, he—.” Dad snuffed out a double-barreled burst of air. “Come on, sir, we’ll find you some candy. Come on up front.”

“But I’m not supposed to.”

“It’s Halloween. We’ll defy the law.”

He could see better up by Dad. Most houses were dark, and almost no trick-or-treaters were circulating. When Dad found a promising site (decorated, porch light on), Jordan hesitated.

“Go on, Ace.”

“Will you go with me?”

“Jordan!” Dad indicated the house with his thumb like an umpire calling an out.

The boy dried the cold, wet mask on his knee and put it back on his face. Re-Eviled, Re-Gestured, he ran to the front door and rang the bell, ready to flee if any criminals sprang out. He counted to five, then ran back to the pickup.

Over the next twenty minutes, Jordan accumulated only eight pieces of candy and a toothbrush from a lady who said she was a dentist. Back in Chicago, you got half a pillowcase of candy on Halloween. Several homeowners said they’d run out, he should’ve come earlier.

Eventually they stopped at a stucco house with lighted windows and a front-porch banner of the Holy Ghost descending as a dove. Jordan ran up, rang the bell, and raced back to the car, ding-dong-ditch. As he was getting in, Dad said, “Hey, you didn’t wait long enough.” A Jabba the Hut lookalike stood backlighted in the door. “Look, it’s Mr. Reiersgord. Go on.” The Gesture evilly returned to the porch and presented his flimsy Walmart bag. Reiersgord’s bearded jowls blubbed over the collar of his orange Cowboys jersey. Could that rubbery face be a mask, hiding a fatso monster?

“We don’t have any candy,” he said, “but I got something even sweeter.”

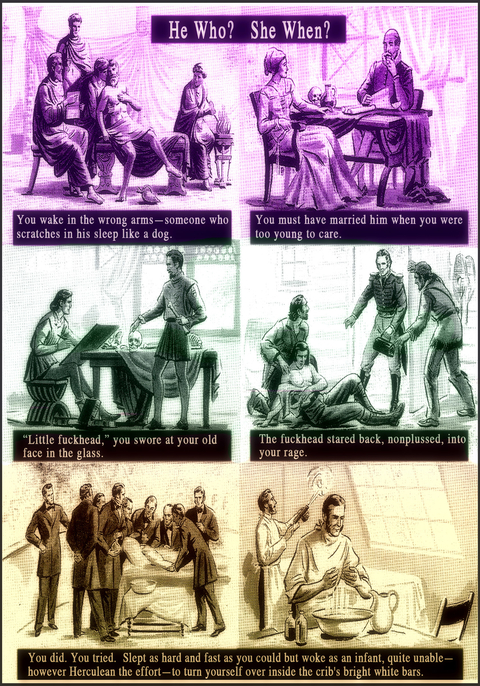

He offered a postcard from a stack in his hand. On a background of candy corns were two illustrations:

Jesus, with a lamb draped around his neck (right)

A cackling Devil with a face like the Evil Gesture’s (left)

For those who couldn’t figure which was which, the images were labeled JESUS and SATAN.

A message read:

DON’T BE TRICKED

Celebrating Halloween

It’s the DEVIL’S Day!!!

Whom Shall Ye Serve?

SATAN, Prince of Darkness?

Or JESUS, Lord of Life?

God’s Love:

It’s the Sweetest Treat of All!!

—Reiersgord’s Ice Cream Parlor

Jordan turned the postcard over. On the back was printed: “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life!!!” Along the bottom, the card advised: “Bring this card in to Reiersgord’s Ice Cream Parlor at 436 E. Grange Avenue and recite John 3:16 for a FREE single-scoop ice cream cone of any flavor (except licorice)!!! Limit one per customer.”

Mr. Reiersgord asked, “You given your life to Christ as your personal Lord and Savior, young man?”

“Yes, sir.”

The wrinkling of Reiersgord’s brow indicated he was not altogether persuaded. “Then you ought to know not to wear an evil costume like that.”

Jordan dropped the card in his bag. Reiersgord’s eyes followed the motion of the boy’s hand. “Pretty meager haul,” he said, not without sympathy. He was an ice cream man, after all.

“We missed the Trunk-or-Treat,” the Evil Gesture said.

(“Trunk,” a boy’s lips whispered within the mask.)

“’Course you did, heading out at nine o’clock at night, practically. Don’t tell me you’re the Rawls boy? Jordy, is it?”

“Jordan, sir.”

“Well, why didn’t you say so? Show me your face. Should’ve known you were a Rawls just by the stance. Your grandma’s right: spittin’ image of your uncle at that age. Now, you ask yourself if you’re one hundred percent sure that if you’re run over by a cement truck while you’re out trick-or-treating tonight, you’ll wake up in the arms of the Lord.”

“Yes, sir, I am.”

“I’d like to believe that. Same for your brother. Would like that reassurance. Your uncle, I mean. Because I remember him.” He shook his head. “You know, we had a boy, Mrs. Reiersgord and me, but he went to be with the Lord. April the twelfth, 1992. We have that faith, we do earnestly contend. Whereas Aaron—”

Dad honked the horn, and Mr. Reiersgord waved. He eyed the Walmart bag. His plump fingers rummaged in his pockets and came up with a dollar coin, a paperclip, a matchbook, and an unopened roll of TUMS. “Tell you what, I can offer you a dollar or the TUMS. Taste like candy, and they work pretty good if you got acid reflux, which I don’t know if you do. I’m not offering the matches, you’ll burn the house down. So what’ll it be?”

“The TUMS,” Jordan said.

“TUMS it is, but you ask your folks before you try them.”

“Yes, sir.”

§

That night Mom and Dad tucked Jordan into Aaron’s old bed, and they made up an air mattress on the floor for themselves. (For now Su Ellen was sleeping in Aunt Staci’s room, near the living room, so the grownups could hear her cry from the living room. She’d be moved later on.) They kissed him before slipping out and closing the door most of the way. But just as Jordan began following the children carrying shovels and a Styrofoam headstone to bury their dead guinea pig, the bedroom door cracked open, tipping him out of the drift-boat of sleep.

A black figure entered. Grandma. “Scoot.” She lay down beside him, Fixodent breath in his ear.

“Ma’am, I got you something.” Jordan reached across her and felt for the TUMS on the bedside table. “For your stomach. Mr. Reiersgord gave them to me.”

Grandma clutched them but did not open them.

“Is Uncle Aaron in heaven?” Jordan said.

“I don’t understand. What do you mean?” Grandma sat up on her elbow and pinned him to the mattress. He was afraid to answer. She turned on a lamp and began opening and closing the desk drawers. “I got all your letters.”

Jordan’s skin prickled. The gospel postcard on the desk drew Grandma’s attention.

“It’s from Mr. Reiersgord,” Jordan said.

“How come he thought you’d need this?”

“I don’t know.”

“Why, he was there the day you went forward in church. Every day you were gone, we reassured ourselves thinking of that.”

After sorting in every drawer in the desk, she gave up, wringing her hands. “I’ll look tomorrow. I can’t seem to find—.” She hunched forward and rocked, face in her hands. Finally, she turned out the light and lay back down on the bed. “Not that there weren’t moments of backsliding. That Halloween, Daddy laid down the law, but it was M-80s and tipping cows just the same. And when Deputy Wurth brought you home in handcuffs! That window cost us three-hundred fifty dollars. Lucky thing we knew him, or your so-called celebrating would have landed you in juvenile hall.”

(“Celebrating,” the boy whispered.)

Grandma heard.

“That’s what you called it, you and that Anoatubby boy. Deputy Wurth called it vandalism, pure and simple.”

The door opened, and orangish light flooded in as if from a spaceport, and within this bright rectangle appeared two silhouettes like Ninjas. They took Grandma’s hands and helped her up.

“Ma, it’s his bedtime,” Dad said. “Come on, you can talk in the morning.”

“Charlotte,” said Granddaddy, “let Jordy be.”

“Jordy?” she cried. “What about Aaron?”

“Aaron’s gone,” Granddaddy told her.

Dad quickly assured, “He’s perfect. No more tears, no more pain. We just—. Come on, Mom, Jordan needs—”

“Gone where?” Grandma said.

“Shh. Come on this way.”

Dad and Granddaddy led her out, each holding a hand. The door closed on Jordan.

(“Celebrating,” the boy told the dark.)

—Russell Working

.

Russell Working is the Pushcart Prize-winning author of two collections of short fiction: Resurrectionists, which won the Iowa Short Fiction Award, and The Irish Martyr, winner of the University of Notre Dame’s Sullivan Award. His stories and humor have appeared in publications including The Atlantic Monthly, The Paris Review, TriQuarterly Review, Narrative, and Zoetrope: All-Story. A writer living in Oak Park, Ill., he spent five years as a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. His byline has appeared in the New York Times, Business Week, the Boston Globe, the Los Angeles Times, the South China Morning Post, the Japan Times, and dozens of other newspapers and magazines around the world.

.

.

Daffodils Jean planted here and there in the woods

Daffodils Jean planted here and there in the woods Trout-lily or Dog-Toothed Violet or Adder’s Tongue

Trout-lily or Dog-Toothed Violet or Adder’s Tongue

Michelle Boisseau

Michelle Boisseau