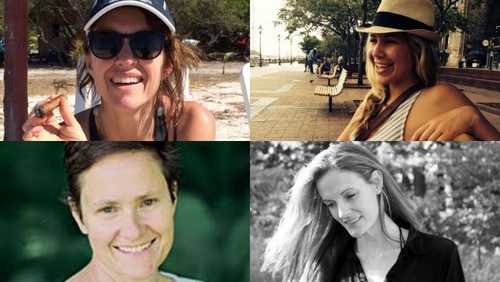

Clockwise from top left: Tracy Proctor, Megan Okkerse, Whitney Lee, & Sheela Clary

Clockwise from top left: Tracy Proctor, Megan Okkerse, Whitney Lee, & Sheela Clary

This is very cool. Last winter in a workshop I was teaching I assigned an exercise on lists. I gave a little lesson, lists in sentences and lists as structure. You can find it written out here (look at the second item in the series): Building Sentences: The Complete Short Course — Douglas Glover | National Post. As an example of list structure, I gave out copies of Leonard Michaels’ story “In the Fifties,” which you can find to read on the Internet here or listen to here. The results were astonishingly varied, intense and emotional. Family stories mostly, as memoirs often are. I managed to sheepdog four of them together for the magazine. A change of pace, a delight to read, not to mention an introduction to four fine new writers: Tracy Proctor, Megan Okkerse, Sheela Clary, and Whitney Lee.

dg

.

List of Do’s and Don’ts — Tracy Proctor

Do adhere to mantras. “Travel light.” “Don’t fence me in.” “Surf’s up.” That sort of thing.

Don’t put corny bumper stickers on the back of your pick-up truck, though. Keep your mantras in your head. Stay cool.

Do adorn your truck with your man toys: dirt bike, road bike, paddle board, surfboard, kite board. Sub-zero cooler. Heavy duty trailer hitch. Camper top.

Do visit lots of kick-ass places across the continent. Allow your mind to be blown. Do feel kinship with the soaring hawk, the lone wolf, the gypsy.

Do maintain high standards in females. If your nubile, fertile girlfriend starts to look or act like a spreading, hormonal woman, tell yourself you’re doing both of you a favor, and move on.

Commit full-heartedly to a dog. Take her with you everywhere: the high ranges of Wyoming, the ducky swamps of Arkansas, the teeming fishing grounds of Key West. The sun-bright shore and ice-cold beers and winding desert trails of Baja Mexico. Confide in your dog. Train her to stay and fetch and ride many miles without peeing. Feed her buffalo jerky and fish tacos. Recognize that you love her and can’t live without her, except when the waves and wind are forecast to be epic. At which time you drop her off with your mom for a month.

Do have many high-quality girls. Brunettes, blonds, redheads, surfer girls, hippy chicks (not too dirty), med students, massage therapists. Fuck and run.

When your mountain-biking buddies are sitting around the campfire on weekend nights, sipping warm tequila and reveling in the precious, waning moments until they have to drag their asses back to wives and kids, pass the flask around again and fake sympathy. When pressed, agree with them that your newest girl is super hot. Agree that she has silky chestnut hair and legs up to here and intelligent green eyes. Agree that you are damn lucky that Miss Super Hot understands – no, endorses – your free’n’easy life style. Don’t tell your buddies that those green eyes of hers see right through to your soul, because that is corny, and because it might be true.

Do not tell your buddies that Miss Super Hot actually wants to marry you. Instead, break up with her.

Definitely do not tell your buddies – or anyone at all – that, one week after you break up with her, she tells you she is pregnant with your child.

Deny it. Fight it. Ask her if she’s sure the baby is yours. Ask her when she morphed into a Bible-thumping pro-lifer. Join Planned Parenthood, and send her a brochure.

Hit the road with your dog. Ignore Miss Super Hot’s demand that you review her birth plan. When she asks you to give her your parenting plan, tell her to go fuck herself.

Drive west, and more west. End up back in Baja.

Kite-board your brains out. Tell your mom you won’t be back east for Christmas this year. Stay away from females. Keep that terrifying secret to yourself.

Get nostalgic on Christmas morning. Send a holiday email greeting to friends and family, including Miss Super Hot: a photo of you in a striped orange hammock, holding a beer, the words Feliz Navidad dancing above your head. Enjoy the warm feeling from all the good email wishes you get in return, until you read the one from Miss Super Hot which says Merry Christmas to you, too and Wow it sure looks nice out there and She’s so glad you’re enjoying yourself in Baja while she and your unborn child are trying to keep warm in Jackson Hole, where you last left them. Get even more upset when you realize she has sent this email “Reply all.”

Do finally answer the phone the fourth time your mom calls you. Do gruffly answer most of her questions. Do not laugh bitterly when she says Miss Super Hot must not understand what “reply all” means.

Do not answer your mom’s question “What are you going to do now, honey?” Because you do not know.

Do get embarrassed when your buddies say that maybe it’s time to get out of the hammock. After a couple more days kite-boarding your brains out, come to the conclusion that maybe they are right.

Do show up at Jackson Hole Regional Medical Center just as Miss Super Hot’s water breaks. Do try not to crumble under her family’s glare.

Do spend the next ten hours walking your dog on the hospital grounds and pacing in the waiting room and getting updates from Miss Super Hot’s family members and learning what three inches of dilation signify and listening to the screeches of infants and the howls of birthing women and the buzz of the phone system and the names of doctors on the intercom. Do close your eyes and smell coffee and antiseptic. Do pop several Advil. Don’t stare at the poster of the island scene.

Do follow the nurse when she beckons you to come to Miss Super Hot’s room and meet your new son.

Do feel your legs tremble when you spy your son swaddled next to Miss Super Hot’s side. Do think that he is the most beautiful thing you have ever seen. Tell Miss Super Hot that. Look into her green eyes when you say it.

Do take the pen the nurse is giving you. Do sign your name on the Birth Certificate next to the word “father.” Don’t protest when Miss Super Hot’s family offers to take your dog for the night so you can sleep there in the hospital room. Do hold your son; marvel at his fuzzy hair and scrunched-up nose; at the stump of umbilical cord. When Miss Super Hot falls asleep, whisper to your baby boy that you can’t live without him. Promise him that when he gets old enough, you’re going to teach him how to kite-board.

—Tracy Proctor

§

Here You Are — Megan Okkerse

Here is what you remember:

You remember my curly blonde hair and the little blue dress I wore at the McCrae’s wedding when I stomped around in the bride’s shoes at the reception. You remember me with my head on Daddy’s shoulder like in the picture he would keep in his office, when he worked day and night, year after year. You remember me playing with the skin under your chin, the soft flesh of your neck as we snuggled together under the pink plaid flannel sheets on those cold winter mornings when you had the heat turned down and the windows cracked because, “fresh air is good for you,” you would say. You remember the day Daddy left and all the names of my elementary school teachers and my soccer games and my long legs striding across the field, me, before I got skinny and sick. You remember my friend Lauren, who had cancer in 7th grade, and Daddy spanking me with the paddle for playing doctor with the neighbor boy when I was five. You remember the day I moved to Daddy’s house and the late night calls you would get from me begging for you to come pick me up and bring me home. Why didn’t you? Did you quietly like the freedom of my absence?

You remember 4th of July at Riverside Park and our long walks around the point. “I can’t walk anymore. I have cramps,” I would whine. You would tell me this, years later when I replaced you with compulsive exercise. You remember the time Daddy came to pick us up after he had shaved off his long beard, and Peter stood at the top of the stairs and refused to come down because he hated seeing Daddy differently.

Here is What I Remember:

Your post-divorce boyfriend Mark Phister and his building that smelled like paint thinner. He wouldn’t come to church with you so instead your Sunday mornings were spent making eggs Benedict and watching Charles Kuralt. I remember that the two of you were going to open a bed and breakfast and travel to France. I remember seeing him that night we walked downtown. He was sitting on the curb with the paramedics, bleeding. His speech was slurred and his breath: what exactly did his breath smell like? I remember the unfinished apartment above his antique refinishing studio. Sometimes finding you in there was like a treasure hunt, but I could always find you. Usually in his bed. You would lift up the covers and scoot over as I curled into your side, and we would tell each other our dreams.

I remember his farmhouse table and the bagels he would toast and top with Mrs. Dash and butter, cutting them up as croutons on the salad. I remember his van. Sometimes, when you had been gone for hours, I would walk to the park to look for you, and there you would be, by the lighthouse in his van talking. I remember his son and his dog Yessa and the monologues he would have with Martha Stewart while he was cooking. I remember how funny he was. He could make my brothers laugh so hard they cried, and I wondered why if he was so funny he made you cry so much.

I remember Bonnie Raitt, James Taylor, Van Morrison, NPR, and Lake Wobegon. I remember how you kept caramel nips and red licorice in the drawer next to the fridge and Häagen-Dazs ice cream in the freezer, one big spoonful for your coffee every morning. I remember Peter and I used to jump from the balcony onto the couch when you weren’t home and we should have died, but we never got hurt. I remember that Peter always ate all the Frosted Flakes, and Elliott hoarded the graham crackers. I ate malt-o-meal while we stood at the counter over the floor heater as the hot air blew up at us.

I remember the day my first grade crush Drew Adams was supposed to come over for lunch, but his mom called and said he was sick. I wondered if he was really sick, or if it was me, because maybe I wasn’t pretty, or maybe it was because we were poor, but I didn’t think we were poor. I remember the time I was learning to drive and Elliott took me to Fresh Air Park. It was dark out, and I drove up onto a boulder and the tailpipe fell off. Elliott drove me home but he had to pull over so I could puke. When we got home and told you what happened, you said, “Well hell, there’s nothing we can do about it tonight. Let’s have some wine.”

I remember you used to take baths every night. I would sit on the tile floor next to the tub, and you would cover your vagina and breasts with washcloths so all that was visible was your flat stomach, the one you pinched and sighed in disgust over. I remember your hair, a shimmering silky grey and your skin, milky, smooth, and unblemished. I remember when you wouldn’t eat, but insisted that I eat more than I was hungry for. You would say, “You don’t really need to eat that much when you’re a grown up.”

You used to tell me I was big boned. I never knew if that was a compliment, but I do know that I’ve always tried to be small—except when I want to be a woman, and then I don’t know what I’ve tried to be except submerged in water, covered in rags.

—Megan Okkerse

§

In my house — Sheela Clary

In my house I have always had the last word, except when Dad was visiting.

When the mudroom was painted, I put up an Irish blessing/curse. I like its surprise ending.

May those that love us, love us.

And those that don’t love us,

May God turn their hearts.

And if He doesn’t turn their hearts,

May He turn their ankles

So we will know them by their limping.

I lie in bed and imagine the routines of single mothers on the infrequent nights when Jim goes out with his uncle, or Tim or Grigori.

To the visitors who perk up when I mention that the house dates to 1783, I point out the wide, uneven floorboards upstairs. I tell them about the newspapers Jim found inside the walls, so old the Ss look like F’s, reporting news about the Papal states. If the visitors like that story, my older daughter usually jumps in about the gravestone for an 11-year-old girl who died in 1810 that lies somewhere in the trees behind the house.

Jim built an addition with a mudroom, our bedroom, a laundry room, our son’s room, and two bathrooms downstairs. I worry that the new upstairs part isn’t necessary, especially the additional bathroom. I grew up in a house for four people with four bathrooms.

There are thousands of small, hard, Leggo pieces. They are not confined to the plastic bins Jim’s mother brought in from Target one day and left on the kitchen table, along with a note offering to help us organize.

I often prepare Bolognese sauce on homebound afternoons. It takes three hours to simmer down the water, milk and wine out of the sauce to a thick consistency. Then I use an immersion blender to blend the meat, tomatoes, onions, carrots and celery into a red brown mush my son will eat.

The kids don’t need to be told what to do or were to go to build up a fire in the fireplace. Jim gently supervises the workings of fire, tools, and wood.

My family creates surprises for me in the basement. I receive these gifts on random evenings throughout the year instead of flowers and chocolates and lingerie. A miniature stable made of twigs and moss, three painted birdhouses, a low bench for the mudroom.

There are several blank walls. One has a print of a shaker apple tree leaning against it on the floor, unattached.

In various chests and drawers there are stacks of undisplayed photos we took when we had just Cecelia, including some from the afternoon she ran around a piazza in Orvieto in her socks because she couldn’t stay still and she was just walking and I wasn’t used to carrying shoes for her.

I worry most about Fiona, my middle child. I worry that a better mother would have prevented her from getting fat, that a better mother would say no cookies and enforce no cookies.

My son Donal complains mostly about the Leggos he doesn’t have, but one morning he complains that there are pictures of only his sisters on top of the bookcase next to my writing desk. I point with satisfaction to my dresser, where I’d only recently cut up a picture of him with face paint on and stuck it in a heart-shaped frame. I’d also noticed the discrepancy.

There was a difficult puppy, and there is still a crocheted baby blanket soaked with her blood in a tightly tied up plastic bag, sitting at the bottom of a laundry basket in the laundry room under my husband’s Carhartts and a jumble of purple underwear.

My father kept his shoes on and gravitated toward the velvety, auburn armchair in a corner of the living room. I worried that Dad would hit his head on the little wooden shelf on the wall above, or that the kids would not be wearing socks, or that he’d ask for the Diet Coke he left in the fridge two months ago for the purpose of having something to drink the next time he visited us.

One afternoon, I stood in the kitchen to hear an update from the hospice nurse via Mom, inserting, “All right,” “See you then.” “Bye.” Then I fell to my knees and keened, and Jim shooed the children outside and came back to hold me.

I keep Dad’s datebook from 2014 on my writing desk. I wonder which day holds his last written words.

I see my father in Fiona.

—Sheela Clary

§

Violet

I used to dance and sway with Violet in my arms and wondered if she remembered a different time, in different place, with a different family.

I first touched Violet’s almond-colored skin when she was two. She wore a daffodil dress and sunshine-colored shoes. But she was terrified, so she cried. But I loved her, so I cried.

My husband and I bought, packed, and flew a stuffed green frog from San Diego, over a vast blue ocean, to the city of Seoul. We gave it to Violet when we first met her. I suppose we thought there were no stuffed frogs in Korea.

Violet’s foster mother carried her on her back. She slept on ours.

I once stood on the shores of the Korean Straight, on the beaches of Busan, the city where Violet’s mother lived. When my feet pressed into the wet sand, and the tiny rocks pushed up between my toes, I wondered if her mother’s footprints lingered or if the ocean swept them away.

When I went to the Korean adoption court, the judge asked me if I would love Violet forever.

When we brought Violet home, many said, “She is lucky she has you.” But no, I was lucky to have her.

Our first weeks together, Violet protested if her feet touched the ground or if I quit moving when she was in my arms. So we walked for hours through the woods and pointed at black-eyed Susans, shasta daisies, and butterflies. When I could finally peel her little body away from mine, my arms ached, and a Violet-shaped sweat stain remained.

Violet was a cupcake her first Halloween.

After she had been home for a few months, Violet crawled into bed with her five-year old sister, Esmae. Their little bodies tangled and twenty little toes peeked beyond polka-dotted sheets.

Violet peed in her pants when her routine was interrupted or if she was nervous. Sometimes, after I removed her soaked clothes, and I cleaned her body, I believed I failed her.

Violet’s first words were, “Eli did it.” Eli is her five-year old brother.

This summer, Violet stood at the edge of Lake Michigan, just behind our house, and threw rocks into the water. She liked to watch them splash.

Last Friday, when I washed her small three-year old body in the shower, I watched the water weigh down her black curls, cascade over the slope of her nose, and stream onto her round taught belly.

Violet wears lots of dresses but only if she can choose them.

With crayons and pencils, Violet’s eight-year old brother, Zachary, still writes stories about the day she came home.

Violet’s laugh fills my heart. That is why I tickle her.

Now I dance and sway with Violet in my arms and I wonder if she forgets a different time, in a different place, with a different family.

—Whitney Lee

.

Born and raised in Tallahassee, Tracy Proctor now lives in New York with her three children and a hound dog. Her short stories have earned a Pushcart Prize nomination, won contest awards and been adapted to stage. She’s currently working on an historical novel set in Florida during the Spanish Empire and perfecting her sangria recipe.

Megan Okkerse is pursuing her MFA in Writing at Vermont College of Fine Arts. She teaches creative writing workshops in Charlotte, NC, and is a reader for Hunger Mountain.

Sheela Clary has taught English and Latin in the Bronx, Italy and with the Peace Corps in Papua New Guinea. She is an MFA student in Creative Nonfiction at Vermont College of Fine Arts and lives in Western Massachusetts with her family.

Whitney Lee is a physician in the Chicago area. Her work has appeared in the Huffington Post and Women’s eNews. She is currently an MFA student at Vermont College of Fine Arts. She lives with her husband and four children.

.

.