.

1

My brother!

I wait, holding my breath, for him to find me. But for the moment the flat is silent.

So silent that high up though we are the sounds of the street drift up to me.

Where is he? What is he up to?

I strain to hear if he is on the move, in search of me.

Patience. I always tell myself I must have patience in situations like these. After all, it’s not as if we have something else to do when this is over. We have all day and every day. So what are ten minutes here or there? Or an hour. Or even two.

Was that a sound? I stiffen in my corner between the wardrobe and the wall. I listen, but everything is still. Then I hear it again. A board has creaked. My brother is approaching.

But then the silence returns.

How long should I wait? For it sometimes happens that he forgets that we are playing and lies down somewhere and falls asleep. Or opens the fridge and makes himself a sandwich, then sits down with a magazine to eat it. And when I finally come across him and ask him what has happened he looks at me blankly. Don’t you remember? I say. We were playing. You were supposed to find me.

That was yesterday, he says.

No, I say. It was now. I went to hide and you were supposed to find me.

That was yesterday, he says again, munching his sandwich, gazing into my face.

It may have been yesterday, I concede, but it was also now.

Clearly, though, it has ceased to interest him. He’s like that, my brother. One minute pestering me to play with him, the next indifferent. He seems to inhabit many different worlds, all with complete equanimity, and each one as though it were the only one, but they are hermetically sealed off the one from the other and often in total contradiction the one to the other. Thus sometimes he will stand for hours behind some piece of furniture, or at the window. Nothing will budge him. Not the mention of food or a walk or even a game, And then he will run through the flat as though pursued by a demon, screaming and whimpering and begging whatever he feels to be pursuing him to desist, to call off the chase. At first I was afraid the neighbours would hear and either come and complain or call the police. But when neither of these things happened I realised that the walls, floors and ceilings of these old apartments are marvellously soundproof and that we could make as much noise as we wanted and no-one would hear.

Then he will beg me to take him out and in the street he will either walk alongside me, nodding occasionally as I speak, like any respectable citizen, or run round me like a dog, dart up alleys or into half-open doors, so that I have to chase him and grab him and then hold him tightly until I sense that the fit of restlessness has passed.

He does not seem aware of these sudden changes of mood, inhabits, as I say, each of them as though that was where he had always lived. Sometimes he will eat up everything that is in the fridge and at other times go for days without food. At first I thought this would make him ill and I tried to remonstrate with him and force him either to desist from eating or, on the contrary, to eat. But he is as stubborn as he is strong, and anyway I soon realised that he must also have a remarkable constitution, for nothing seems to upset his stomach, neither excessive eating nor quasi-starvation.

I look at my watch. Surely it is time to go and look for him myself. If he was still playing he would have found me long ago, Yet I hesitate, knowing how upset he gets if I don’t play ‘properly’, as he puts it, and come looking for him without having given him time to search for me himself. On the other hand I don’t want to go on standing in my corner between the wardrobe and the wall if he has forgotten that we are meant to be playing and is lying down on one of the beds and sleeping, or flicking through one of the innumerable magazines that lie scattered about the flat where, barely opened, he has left them. If I come upon him like that and challenge him, reminding him that we had agreed to play and that I had spent the last hour hiding under one of the beds or squeezed behind the sacks of rotting potatoes in the pantry, he pretends he has not heard and goes on sleeping or turning over the pages of his book. I think he does not understand what I am saying. He turns his face towards me and looks at me, not as one looks at a person but rather as one scans the sky, searching for a cloud.

Ah! That was definitely him, creeping through the flat, approaching my hiding-place. He does not like me to hide too well, he has sometimes got into a state when he could not find me. So I crouch under tables or stand behind doors, so that I appear to be hiding but can in fact easily be found. I have often stood here, in one of the spare bedrooms, in the narrow space between the wardrobe and the wall. He comes into the room, spots me, but pretends he has not seen me, and goes out again. He thinks I imagine I have not been noticed. He goes on along the corridor, entering various rooms, walking round them cursorily, then makes his way back to the room where I am, comes straight up to me and pulls me out into the middle of the room, where he proceeds to embrace me, his soft wet lips making an uncomfortable impression on my cheek. Then he drags me to the nearest bed and we lie down in each other’s arms and often go to sleep like that, only to wake up cold and confused to discover that the sun has set and we are in the dark.

I must have made a mistake. The flat is silent as the grave. If a board did creak it was probably only caused by the central heating coming on. I step out of my corner and strain again to hear. What is he doing? Sometimes he is the most methodical of men, slowly working his way through each of the rooms, and in each room looking behind every sofa and every curtain, under every bed and every table. At others he flies through the flat, hurling doors open, glancing round and rushing out again, banging the doors behind him. But then he will suddenly lose interest and go out onto the balcony and immerse himself in the spectacle of the street below. If I come out and find him there, though, he will, as often as not, berate me for having broken the rules, or burst into tears and wail inconsolably, so that I have to drag him inside for fear the neighbours will see or hear. But at others he will look up surprised and welcome me, and we will stand side by side, leaning over the balcony, looking down into the street below.

He must have gone to sleep. He seems to have this capacity to lie down at any time of the day and immediately fall asleep, like a puppy or a kitten. But it’s a light sleep and if I enter the room he will, as often as not, open his eyes and turn his head, until he can see me. He will give no sign of recognition but watch me carefully. If I leave the room he will simply close his eyes and drift off again. Rarely can I come right up to him without his waking up. And that is usually after one of his bouts of hyper-animation, when he will sometimes sleep, dead to the world, for two or even three days and nights. This, however, has not happened for some time.

I leave my corner and go to the door. If I hear him I still have time to get back to my so-called hiding-place. But the flat is silent as a tomb. One might almost imagine that I was alone in it, and that it had been sealed off from the world forever. I put my head round the door. Silence. Should I give him another few minutes or is that simply condemning myself to anxiety and frustration? I step out into the corridor and the loose board creaks loudly beneath my feet. I freeze. If he is looking for me he will approach, without a doubt, and I will still have time to dart back into the room. I wait, straining my ears, but the flat remains silent. I resume my advance. The door of the next room is closed. I cannot remember if it was closed when I ran past it to reach my hiding-place. I have the feeling that it was. But then again, it might not have been. Try as I may, I cannot remember for certain. Should I open it or simply creep past it? If I open it I risk making a noise and if he is still looking for me he will be alerted and it will be too late for me to retreat to my original hiding-place. On the other hand he may have gone in and fallen asleep on the bed, if it is one of the rooms with a bed in it, and then my search for him will be over.

Surely if he had gone in and lain down I would have heard as I stood hiding and listening? On the other hand for the first half hour or so I was lost in my own thoughts and might perhaps have failed to hear him. He can, when he wants, be remarkably quiet when he comes looking for me in the course of our games. Sometimes he has given me quite a shock, jumping suddenly out at me and shouting to show he has found me.

I decide to leave the door closed and move on towards his room. Though he will lie down on any bed he finds if the fancy takes him, most often he returns to his room, or at least to the room that was originally his, for we both of us change rooms, and beds, as the mood takes us.

The door to the bathroom is shut and I stop for a while and listen, pressing my ear to it. Unless he has fallen asleep in the bath, and that has been known to happen, he is not inside. Beyond it, the kitchen door is open, but one glance is enough to show that he is not there.

Beyond the kitchen the corridor turns at a right angle. I dread this corner, for he sometimes likes to lie in wait for me there and leap out with a howl, and however much I prepare myself, it is nearly always a shock. I literally feel frightened out of my skin – as if my body had leapt into the air and my skin had stayed behind. It takes me a considerable time to recover. My heart beats so wildly I think I am going to have a heart attack. I have to lie down on the nearest bed, which is that of our parents, and in some instances I have fallen asleep there and not woken up for several hours, once even for a whole day.

I stand on my side of the corner and listen. However much of an effort my brother makes to try to breathe quietly, or even to hold his breath altogether, a little rasping noise always escapes him, which alerts me to his presence. It is sometimes difficult, though, to distinguish this noise from that of the water in the pipes. I close my eyes in order to hear better. The corridor is very dark here, for no window lights it and the bulbs are weak in the flat and anyway there is none near the corner.

I stand then and listen. Nothing.

I wait. Still nothing.

I advance again slowly, taking care to make no noise. I stop again, straining my ears. Perhaps my brother is in his room, listening to music. He may have forgotten all about our game, and have settled down with his music. His door is shut. Should I open it and risk disturbing him? Or simply let him be? After all, this might be an opportunity for me to read something or listen to a bit of music myself.

I decide to leave his door unopened but to go on with my search through the flat. If I do not find him anywhere else I can always come back to his room and open the door and see. I have reached what used to be the living room in the days of our parents, but it is now just another room, in which we sometimes sleep, on one of the large sofas, or in which we eat when we don’t want to eat in the kitchen because it feels too squalid, and we don’t want to eat in the dining-room because it feels too stuffy.

It is empty.

I walk round it, nevertheless, looking behind the curtains, though since it is I who was meant to be hiding I don’t know why he should be there. And of course he isn’t. I sit down on the sofa in front of the television and look at the white screen and at my pale reflection in it. Much as I dislike looking at myself in the mirror, I like seeing my shadowy reflection in the milky screen. Perhaps because it reassures me that I am really there while not forcing me to contemplate my features. And it might not be me, it might be someone else, all I can tell is that there is someone there, in the room. The television confirms that. Someone who is most likely to be me, since I sense that I am in the room, sitting on the sofa, looking at the screen.

All of a sudden I see, on the screen, something moving behind me. I turn round. It is my brother. He comes towards me, his mouth open, his face purple with anger. I stand up and take hold of his wrists. I know what he is trying to say. I should have been hiding, I have spoilt the game by my lack of patience, I am never prepared to play properly. I hold his wrists, and though he is a good deal stronger than me he does not seem to know how to use his strength to best effect. He spits at me and then begins to cry. I let go his wrists and draw him to me. His face is wet and when I seek to comfort him I taste the salt of his tears on my tongue. I want him to sit down beside me on the sofa, but he drags me out of the room and across the corridor. He pushes open another door and pulls me to the bed. We lie down on it together and very soon he is asleep.

—Gabriel Josipovici

.

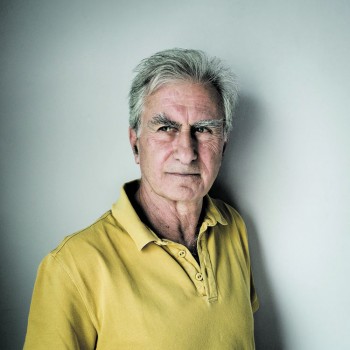

Gabriel Josipovici was born in Nice in 1940 of Russo-Italian, Romano-Levantine Jewish parents. He lived in Egypt from 1945 to 1956, when he came to England. He read English at St. Edmund Hall, Oxford and from 1963 to 1998 taught in the School of European Studies at the University of Sussex. He is the author of eighteen novels, four books of short stories, eight critical books, a memoir of his mother, the poet and translator Sacha Rabinovitch, and of many plays for stage and radio.

Read Numéro Cinq‘s interview with Gabriel Josipovici here.

.

.