Murals all over North Korea honor the regime and denounce

Murals all over North Korea honor the regime and denounce

America and Japan. Photo © Yuri Maltsev.

A Star for Choi Deok-geun in the Hall of the Spooks

In the Far Eastern seaport of Vladivostok, Russia, where I used to live, you sometimes see North Korean guest workers in grocery stores around town. In a typical Russian “productery,” you do not push a cart around piling in cans of soup and tubs of ice cream; you stand at the cash register and tell the clerk what you want, and she grabs it from the shelf behind her and rings it up. But the North Koreans project a truculent self-confidence, despite their modest appearance. They are pencil-necked and knobby-elbowed, wearing torn jeans or plaid trousers, haircuts they seem to have given themselves, and lapel badges of their late leader-god, Kim Il-sung, yet they barge up to the front of the line and bark orders in pidgin Russian, gesturing at whatever they want. Beer! Oil! Rice! To my surprise, the other shoppers stand by patiently, rather than cursing and telling the North Koreans to wait their turn, as they would any Russian who cut the line. The Koreans are regarded as a species as alien as Martians. No point even trying to explain to them the concept of a grocery store line.

The guest workers can still be found in the city, but in 1997 I was editing the Vladivostok News, the Russian Far East’s only English-language newspaper, and the North Koreans were a story. Once I approached three of them who were buying beer in a kiosk near our apartment. Hoping for an interview, I attempted to strike up a conversation, but I was handicapped by my poor Russian. I blurted out, “Are you North Koreans?” They glanced at each other with expressions that said, Well, duh.

I said, “I’m American!” and offered a great big friendly grin to show we meant no harm, we Yanks, large-hearted romantics that we are, galumphing about the globe to distribute chewing gum, rap music, gender anxiety, carpet bombings, and elected governments that have a distressing tendency to collapse into kleptocracies.

One North Korean wore a larger badge than the others–some kind of crew boss or commissar, perhaps. He told me, “Then we’re enemies.” At this he grinned right back.

My wife, Nonna, who was deputy editor and interpreted for me, called around and found a business that had hired North Koreans to remodel the interior of an old building on Aleutskaya Street downtown. The Vladivostok News has since closed and vanished from the Internet and nobody seems to have saved the print archives, so the story I wrote is lost. But I recall a Russian foreman or building owner cheerfully answering our questions. The North Koreans, however, weren’t so easy to talk to. When we approached them, their panicked eyes darted around in search of an escape.

“We Will Strengthen International Cooperation”: A sign welcomes

“We Will Strengthen International Cooperation”: A sign welcomes

a Russian delegation near Rajin. Photo © Yuri Maltsev.

Various newspapers report that there are about ten thousand North Korean guest workers throughout the Russian Far East, many of them based in remote logging camps in Khabarovsky region north of us, where they first began arriving in the 1960s. The Seoul newspaper Chosun Ilbo recently stated that one hundred fifty thousand North Koreans are working abroad worldwide under conditions it describes as slave labor, the majority of them in China. Many are also employed in Qatar and Dubai, building a stadium, hotels, and golf courses in preparation for the 2022 World Cup. “Most of their fellow workers from Vietnam, India and Nepal get off at dusk, but the North Koreans often labor on in the glare of fluorescent lamps until late at night,” Chosun Ilbo reports. Ninety percent of their salaries are said to go to the regime.

The Russian crew boss told us that he paid the men’s wages directly to their government officials; elsewhere in the Russian Far East, the workers reportedly receive worthless scrip they supposedly can exchange for rubles. If they were willing to put up with this, it was not the boss’s concern. So what was in it for the guest workers who came to Russia? For timber crews isolated in logging camps in the taiga, it is hard to say. Maybe just food. In Vladivostok, though, North Koreans can earn extra cash doing odd jobs. Sometimes in the evening they went doorbelling in the neighborhoods where they worked, offering their services.

Dressed in traditional Russian felt boots and a tattered coat without sleeves, a North Korean lays brick in Vladivostok. Photo © Valentin Trukhanenko.

Dressed in traditional Russian felt boots and a tattered coat without sleeves, a North Korean lays brick in Vladivostok. Photo © Valentin Trukhanenko.

Vladivostok has long been a battleground in the spy-versus-spy conflict between North and South Korea. The Kim regime claims to be the sole legitimate government on the Korean peninsula, and it presents the government in Seoul as collaborators with the “Yankee bastards.” So it is unsurprising that the intrigue would spill over into the Russian Far East, where both countries maintain consulates. The failed state’s ire toward its successful rival in Seoul erupted in October 1996 with the murder of Choi Deok-geun, a South Korean consular official who was killed in his apartment stairwell in Vladivostok. Choi officially served as the consul for arts and culture, but his duties clearly extended beyond that. He reportedly was investigating North Korea’s drug trafficking and counterfeiting, and when his corpse was discovered, there was a dent in his skull and poison in his system of a type North Korea was known to use, The Dong-a Ilbo reported in 2011 in an article on Seoul’s request that Russia reopen the unsolved case. Korean observer Robert Neff has noted in the blog The Marmot’s Hole that Choi is now memorialized by a star embedded in the security exhibition hall of the National Intelligence Service in Seoul. Each of the forty-six stars represents an agent who died in the line of duty.

After we visited the construction site on Aleutskaya, the North Korean consulate in nearby Nakhodka, which previously had refused to comment, suddenly called the newsroom to ask what we were up to. When he hung up, the phone rang again. An officer of the FSB, an agency formerly known as the KGB, wanted to talk to Nonna. Somehow he had learned about our story (perhaps listening in on the North Korean consulate?) and asked what was going on.

Nonna explained what we were working on.

“You’d better be careful,” he said. “We don’t want to end up with another dead body on our hands.”

Fish Soup and Cookies in a Land of Plentiful Frogs

We heard there were North Korean workers in Khasan, down on the border, so we caught the train there. The village, home to seven hundred forty people, used to be a bustling portal between North Korea and the Soviet Union, but this ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the elimination of trade subsidies for the socialist little brother. When we arrived, we found a few glum North Korean workers in Khasan Station, waiting to catch a train home. Piled at their feet were cheap bags of a sort Russian shuttle traders would bring back from China, stuffed with whatever these workers had bought in Vladivostok. Food, perhaps, maybe clothes. I introduced myself as an American reporter. They would not touch the official red-bound Russian press I.D. I tried to show them.

Murals all over North Korea honor the regime and denounce

Murals all over North Korea honor the regime and denounce

America and Japan. Photo © Yuri Maltsev.

We found some railway employees, who said they had seen coffins on trains heading back into North Korea, bearing the bodies of guest workers who died cutting timber in the taiga. It is also possible that every so often a coffin was bringing back what might be described as a living corpse. When North Korea captures a runaway “traitor” in a foreign country, the secret police reportedly drug him, break his legs so he cannot escape when he wakes up, and return him home in a coffin, a former refugee reports. South Korean media state that Pyongyang’s secret police operate with impunity in the timber camps of the Khabarovsky region north of us, torturing and executing workers. Yet it seemed that nobody wanted to go home. Galina Kachanova, a Khasan train dispatcher who had traveled across the Tumen River several times to inspect rails and work out timetables, told us that when she last visited Tumangang, three of her seven cross-border colleagues had died of malnutrition, among them a father who starved to death because he was giving his own rations to his children. These were railway officials, not prisoners of the North Korean gulag.

“They’re brought up as very fanatical people, and usually they don’t admit that they have hunger in their country,” Kachanova said. “But lately they’ve become more open about it.”

Leaving the station, we headed out into the village.

There isn’t much to see in Khasan. Ramshackle cottages, gravel roads, soggy ditches, weedy rail yards, sidewalks of concrete slabs buckling up and down, fences of splintery wood or sheets of corrugated rust, blocky two-story Soviet apartments shedding plaster. A windowless building was collapsing in decrepitude, filled with scraps of ceiling plaster, living shrubs and saplings, rusty box springs, shattered bottles. The lower part of the village was sinking into swamp. The air breathed the perfumes of sea breezes and coal smoke and diesel and river mud and young, sappy leaves on the trees.

We followed a road paralleling the train tracks that crossed the Tumen River up ahead. The tracks bridged a murky waterway that empties into the Sea of Japan a few miles downstream. A fence ran between us and the rails, and we came upon some North Koreans repairing the tracks. As I photographed them, they straightened up and muttered at each other, hefting their tools.

From Khasan you can see across the Tumen River into North Korea and China; the village borders both countries. On the other side, green hills rumple up into low mountains under a gray ceiling of felt. I had read that from the opposite bank all the way to the DMZ, the frog population had disappeared, devoured by hungry citizens. Two million people died during the famine of the mid-nineties, and hunger, like a specter in a medieval woodcut, is still reaping souls. The regime blamed floods, and then droughts, then more floods. Calamities befall North Korea as nowhere else, to hear the government tell it. The regime can’t get a break long enough to demonstrate the radical efficacy of its agricultural collectives. Yet when its people were on the brink of starvation in 2012, North Korea launched a missile that caused the West to threaten to cut off cash and food aid. This in a country where malnutrition has shrunk the populace to the point that the army has lowered its minimum height requirement to four feet seven inches, or slightly taller than the average South Korean fourth grader, according to NPR. A third of North Korean children are believed to be “permanently stunted” because of a lack of food.

In her new memoir, In Order to Live, escapee and human rights activist Yeonmi Park recalls growing up as the daughter of a North Korean wheeler-dealer who was trading in stolen metals–the only way he could feed his family. In times of hunger, she writes, starving mothers abandoned their babies to freeze to death in alleys. Bodies lay in trash heaps and floated down rivers, and she and her sister once saw the corpse of a naked young man beside a pond where he had dragged himself for a last drink of water. His stomach had been torn open, apparently by hungry dogs. Winter was not the season of death. Spring, when food runs out and the farms have yet to produce crops, is when most people died of starvation. “My sister and I often heard the adults who saw dead bodies on the streets make clucking noises and say, ‘It’s too bad they couldn’t hold on until summer,’” Park writes. She, her sister, and her mother also found it hard to survive after her father was arrested and sent to prison. They ate herbs and plants and cicadas. One boy who had a cigarette lighter showed her that if you cooked a dragonfly over the flame, it “gave off an incredible smell like roasted meat, and it tasted delicious,” Park writes.

A scrawny ox pulls a cart near Rajin, North Korea. Photo © Yuri Maltsev.

A scrawny ox pulls a cart near Rajin, North Korea. Photo © Yuri Maltsev.

Escapee Jang Jin-sung, formerly North Korea’s poet laureate, writes of returning to his hometown, Sariwon, in 1999, not long after Nonna and I first visited Khasan. In Dear Leader: My Escape From North Korea, he recalls being shocked to find his old friends were starving. A girl who used to pretend to be his bride in their child wedding games now resembled a gaunt old woman. He inquired after old friends and neighbors and learned that many of them had starved to death. On the streets, merchants were offering wares and services that would not even appeal to a bum in Seoul. One woman was trying to sell a flask that could be filled with hot water to keep the buyer warm; evidently there was no longer any heating. For ten won–about a penny–another let customers use her bar of soap and basin of water to wash their faces. The city’s water supply, it turned out, had dried up with yet another one of those droughts. Jang saw another woman in Sariwon selling comforters stuffed not with cotton but with the filters of smoked cigarettes. All around were inspirational slogans:

Death by Firing Squad to Those Who Waste Electricity!

Death by Firing Squad to Those Who Disobey Traffic Rules!

Death by Firing Squad to Those Who Spread Foreign Culture!

Death by Firing Squad to Those Who Hoard Food!

Death by Firing Squad to Those Who Gossip!

As Jang headed back to the train station on his way home, a siren sounded, and police surrounded the square and drove everyone into the center with their rifle butts. They dragged out a terrified man in work clothes and held a five-minute People’s Trial. The sentence was death. The soldiers formed a firing squad. Everyone in the plaza was forced to watch, but as the volleys were fired Jang looked up to the sky so as to avoid seeing the moment of death. As he later wrote in one of the dissident poems he secretly composed:

The prisoner’s crime: theft of one sack of rice.

His sentence: ninety bullets to the heart.

His occupation:

Farmer.

“The man riddled with bullets for stealing rice had been a starving farmer,” Jang writes. “Even someone who worked the land could not find enough to eat.”

On the edge of Khasan we turned down a dirt road, approaching the river through a patchwork of dacha gardens and neglected military pillboxes. One feels that the river forms the border, but a sliver of Chinese territory separates Russia from the riverbank at this point. Nonna and I came to a sign ordering trespassers back or we would be shot without warning. We had nearly walked into China. Just then a voice yelled “Halt!” A Russian soldier we had not noticed came out of a little guardhouse checked our papers. He eyed mine suspicously, Americans being a rarity in Khasan. Ah, but my clever wife had thought of everything when she applied for my visa to come to Russia back in January. The form had asked where I would be traveling in the country, so she listed every city in the Primorye region which was closed to foreigners. Some bureaucrat had rubber-stamped the document, and I now had permission to be in towns that normally would have been off-limits to an American, among them Khasan. Several years later, when we returned on an assignment for BusinessWeek, I had no such documentation, and we were arrested by four soldiers aiming AK-47s at us, and they kicked us out of town. But this guard just waved us back up the road toward the village.

By this time evening was descending. Possibly it is heartless to say this within sight of a famine-afflicted land, but we were hungry, and we could not find a restaurant in the village. The tiny station had no café. The overnight train back to Vladivostok would not leave for hours, and there would be no dining car on a provincial spur from Khasan. (While the distance is short as the crow flies, by rail it was a long trip around Primorye’s rugged coastline and required a recoupling of the cars in the Ussuriysk.) The kiosks offered limited options–packages of hot dogs and imitation crab, Ramen-style noodles, Snickers bars, chips, Choco Pies. Having nowhere to cook any food, we bought some cookies and drifted down a gravel road. Evening slanted across the hills and cottages and vegetable gardens in what might have been an ancient Russian village on the Volga but in fact was in the extreme reaches of Asia. As the good Slavic sun went down, it gleamed on channels of ditch water, ignited slabs of the prefab Soviet buildings, warmed the treeless earth of No Man’s Land that separated us from China, and dappled the frogless bogs of North Korea.

We came upon a villager named Raisa, who was hoeing her potato garden, and asked her a question or two. She didn’t have much to say about North Korea. What she wanted to hear about was us. Where were we from?

Vladivostok, Nonna said, but he’s an American correspondent.

Raisa’s eyes lighted up. An American! What was I doing in Khasan? Was I a spy?

No, a journalist. Editor-in-chief of the Vladivostok News.

Well, this was just terrific, in Raisa’s view! She was delighted to welcome a foreigner to Khasan. Raisa invited us to join her and her husband, a Tatar named Farid, for dinner, and we followed her to their apartment. How homey it seemed, and how exotic just the same, to enjoy Russian village hospitality here on the border of North Korea, to leave your shoes at the door and step into your hosts’ worn slippers, to settle on stools around the kitchen table, to butter slices of black bread, to blow on spoonfuls of scalding fish soup, to nibble on a dessert of Bird’s Milk chocolates and cookies (ours). Yet we could see across the river into a land where railway officials starve in order to feed their children, and where Jang, the poet, once encountered a famished woman in a market in Pyongyang with a sign that read, “I sell my daughter for one hundred won.”

Russian and North Korean flags fly at Khasan station to welcome

Russian and North Korean flags fly at Khasan station to welcome

Kim Jong-il in a visit in 2000. Photo © Yuri Maltsev.

Farid set out a bottle of vodka and shot glasses, and we toasted international friendship. Switching its tail, Rajah, their irritable tomcat, skulked into the room. Farid had trimmed the cat like a lion, shearing it except for a fluffy mane and a tuft at the end of its tail. Raisa said she was knitting a sweater from the fur she trimmed off the cat. This strikes me as implausible, but it is what she told us. The couple insisted that we remain with them until our train departed. They offered us their comfiest chairs, and Raisa plopped Rajah down in my lap, as if this were a pleasure reserved for honored guests. We watched a selection of their Indian videos. “We’ve always been crazy about India,” she said. I cannot recall if they had ever been there or if this was a theoretical interest.

Maybe it was the vodka, or the lateness of the hour, but I caught only part of the movie before I fell asleep. A villain shoved a beautiful woman into a swimming pool, and a crocodile that was lurking there chomped off her face. Luckily, she secured a good plastic surgeon, allowing her to find work as a supermodel. When Rajah jumped down, Raisa captured him and set him back in my lap, waking me.

Eventually she said, “Oh, you’d better get going,” and stopped the movie. Raisa walked us through the dark village to the station. There were no streetlights, and the skies were spectacular. All of Russia, all of China, all of North Korea had ascended in the celestial sphere, leaving nothing but stars and, in this salient, at least, the chirping of frogs. From the station we caught the sleeper to Vladivostok. Trains rock you to sleep, and I rested well.

Back home our story ran with the additional quotes and color from Khasan. Despite the worst fears of the FSB, there were no attempts to assassinate us. Which is just as well. Like most people we wanted to live, and besides, unlike Mr. Choi, nobody would ever memorialize us with a star in the hall of the spooks.

.

The Trade in Cross-Border Wives

Several years later we got another glimpse of the Hermit Kingdom when we caught a bus to Yanji, China, where I wanted to write about the North Korean refugees there. Yanji is the capital of Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture, where more than a third of the population of two million people are ethnic Korean citizens of China. An additional two hundred thousand North Korean refugees live in China, human rights organizations estimate.

Nonna and I took a tour bus from Vladivostok along with my stepson Sergei and some friends from what is now called Far Eastern Federal University, where I was taking Russian classes. We were visiting a professor friend of ours who was teaching in Yanji for a year. Part of the way we skirted the Tumen River, where the North Korean bank is lined every kilometer with a guard station. In the last three years, the Chinese have extended fencing and coils of barbed wire along their bank of the Tumen and Yalu rivers, but smugglers and refugees still find a way to wade or swim across in summertime or make a slippery dash to freedom on the ice in the winter. But at that time I noticed no fence on the Chinese side. Those who have the money bribe the North Korean border guards to allow them across; otherwise, they risk their lives when they flee.

“Border guards remain authorized to shoot to kill persons who cross the DPRK border without permission,” states a report by a U.N. commission, released in 2014 as an indictment for a possible future prosecution of North Korea’s leaders for crimes against humanity. “Such killings amount to murder.”

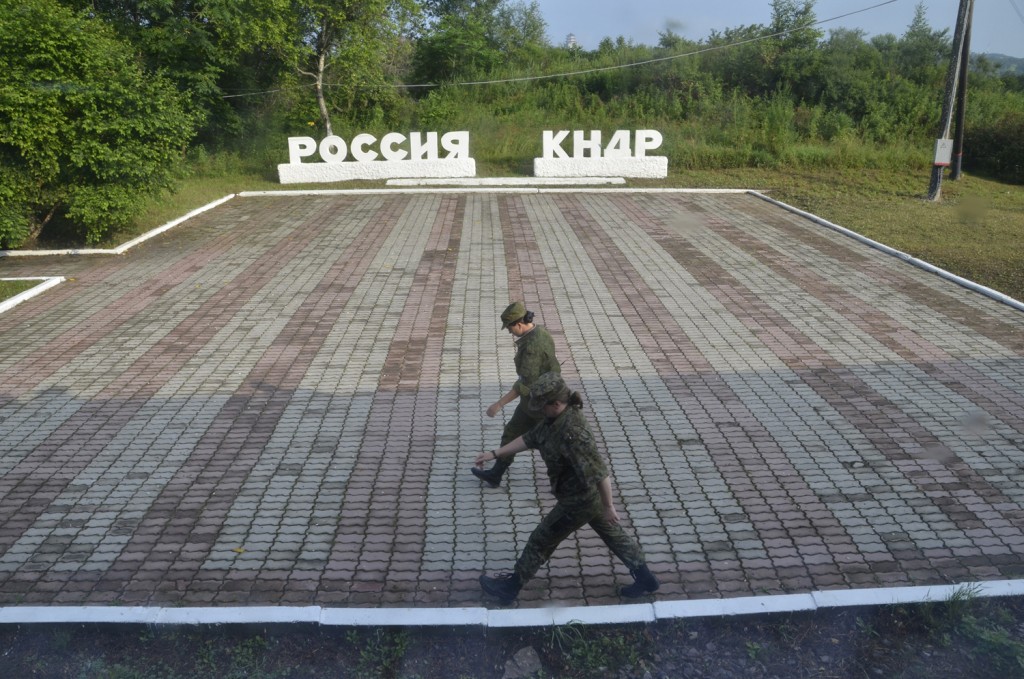

Russia’s border with the DPRK. Photo © Yuri Maltsev.

Russia’s border with the DPRK. Photo © Yuri Maltsev.

Yanji is a bustling city of four hundred thirty thousand people. At night, the multistory buildings downtown are lighted with neon signs advertising food markets, shoe stores, cell phone establishments, karaoke joints. Restaurateurs hang colorful banners with photographs of their tastiest entrees to entice customers. Some signs include a little silhouette of a dog, indicating that man’s best friend is on the menu. As we arrived at our hotel lobby, our tour guide, who was Russian, pointed out a stack of glossy business cards on the front desk, telling us they were from the hotel and we should take some to give to cabdrivers in case we got lost. A few days later, when I gave the card to a foreign pastor and said, “Here’s where I’m staying,” he chuckled and told me, “No, you’re not.” It turned out the cards actually advertised a brothel. Which would relate, I suppose, to the story I would find in Yanji. But I first had to find a way to communicate with North Koreans.

In case you ever find yourself in China writing business stories, you may secure an interpreter through the concierge at the front desk of your hotel. After a series of misunderstandings in which a tour guide who doesn’t speak English takes you sightseeing at a muddy little zoo where rain-darkened zebras chew straw and dispirited howler monkeys cling to a dead tree planted in concrete; after her long-haired boyfriend arrives and tells you he can show you the rock ’n’ roll scene after dark, and by the way, just call him by his English name: Superboy; after he is made to understand that you are a reporter in need of an interpreter–then finally a man in a suit, his dyed hair neatly parted to reveal half an inch of gray roots, will knock at your door and offer to interpret free of charge, not a problem at all, keep your money, he just wants to practice his English. What gives the game away is when your free interpreter leads you through the lobby to a waiting sedan, white in color, with a People’s Liberation Army soldier at the wheel and little Chinese flags fluttering from the front fenders. You are in the hands of some Chinese variety of the FBI or the KGB, and they want you to know that. The chauffeur, too, refuses any payment (he apparently needs to practice his driving), but as long as you are there to write about business, everyone is eager to talk to you and all barriers are swept from your path. Sources cheerfully relate their successes in the topsy-turvy world of China’s commie capitalism. When you are ready to return home, your interpreter may even suggest that you go into business together. If you ask, Selling what? he will tell you, We’ll figure out something. People are right when they say China is business-crazy. At any rate, this is how it worked for me.

But it is different when you’re interviewing North Koreans on the run, so I went through a contact I had arranged. The interpreter and I set out in search of refugees while Nonna and Sergei went shopping. Min-sik (as I will call him) said he knew a North Korean woman who had married a farmer. He drove me out of town along roads through fields plowed by oxen. For many miles on either side of the road, solitary farmers were guiding plows up and down the rows, led by a team of oxen. If they were working alone, it meant they couldn’t find or afford a wife, Min-sik said. Those who were married, however, worked in tandem with the wife, her trudging ahead and leading the ox by the halter while he kept the plow going straight. Most of these women came from North Korea.

Three quarters of the North Koreans in China’s three northern provinces had been purchased as wives or prostitutes, Good Friends, Inc., a Seoul humanitarian organization, reports. Chinese demographics drive the market for women. The rural population of Yanbian produces insufficient women for its Korean bachelor farmers. If you ask villagers why this is, they will laugh awkwardly and say all the women moved to Yanji to work in restaurants and karaoke bars, and who knows, maybe some of them did. Some families buy wives for disabled sons who couldn’t otherwise find a mate, Park writes. Abortion is another factor. Ethnic minorities are allowed some exemptions from the one-child policy, but China’s high abortion rate disproportionately affects girls in this region as it does in the rest of the country. In 2014, Chinese women gave birth to nearly one hundred sixteen boys for every hundred girls, while the natural human birth ratio is one hundred five boys for every hundred girls, Bloomberg reports. That year there were thirty-four million more men than women in China, according to China Daily. In Yanbian prefecture and elsewhere, North Korean women fill in the gap.

On our way to a village whose name I purposely did not learn, we took a detour. Min-sik took me to a spot overlooking the Tumen River and gestured at the opposite bank. There it is, he said. North Korea. The trees on the other side looked spindly and bald, perhaps because they had been stripped of their bark by Koreans desperate for food, as Jang suggests. We could see a village tucked in the foothills. Unlike in China, no smudges of coal smoke tilted from the chimneys. Maybe there was no coal to be had (such things were known to happen in Russia when officials steal the budget for fuel). From riverbank to riverbank, the Tumen looked narrower than the deep, green Toutle River in Southwest Washington state, where I used to swim in my late teens before the eruption of Mount Saint Helens silted it up. North Korea was so close. A ridiculous notion came to me: What if I just swam across, tagged the other shore, and came back? It was early spring, the trees still leafless. It would be freezing. More to the point, I might be shot midstream, or hauled up on the opposite bank by border guards and frog-marched to prison, requiring Jimmy Carter to intervene on my behalf. So, no, then. I guess I wouldn’t be swimming over. It was just a thought.

Bridge over the Tumen River at Khasan. North Korea

Bridge over the Tumen River at Khasan. North Korea

lies on the opposite bank. Photo © Yuri Maltsev.

We headed this way and that through country roads until we found ourselves in a village of redbrick homes, one- or two-room huts, really, of a sort North Koreans call “harmonicas,” built wall-to-wall in long rows. We stopped at the door of one of the units. Min-sik knocked, and a housewife peeked out. The worry evaporated from her face when she recognized him, and she looked over my barbarian countenance with curiosity but without hostility. North Korea’s racist propaganda portrays Americans, black and white alike, as monsters and sub-humans with “paws” and “snouts” in place of normal features, R.B. Myers writes in The Cleanest Race, and one popular novella relates how an American “jackal’s spade-shaped eagle’s nose hung villainously over his upper lip,” his eyes “like open graves constantly waiting for corpses.” (Bear this in mind the next time they call President Obama a “monkey” and a “crossbreed with unclean blood”; they think of us all that way.) Despite having been indoctrinated in such propaganda, the woman politely opened the door and invited us in. I now saw that she had a baby tied to her hip with a blanket.

We sat on the floor while she called her husband on a cell phone. Presently he joined us. I will call her Eun-ju, him Young-shik, as I later did when I revisited their lives in a short story. She was in her late twenties, he in his early thirties. In my story “Dear Leader” I described the real couple’s house through the eyes of the North Korean bride-to-be as she and a marriage broker entered

through a concrete-floored entry room filled with rakes, shovels, buckets, dried ears of corn hanging from the walls, a plow without a blade. Glancing frequently with mute wonder at Eun-ju, the farmer [Young-shik] led them into the living quarters, a single room with an electric cooker built into the floor—a gas unit covered by a lid the size of a truck’s hubcap. A faucet poked its snout from the kitchen wall, but there was no sink, and a plastic trash barrel had been placed underneath it to catch the water. Everywhere there were signs that this was not North Korea: a twenty-kilo bag of rice sat in the corner, color calendars with pictures of girls in swimsuits hung on the walls, and there was electricity to squander: a miniature black-and-white television buzzed with a broadcast of a soccer game. Astoundingly, a bird cheeped from within Young-shik’s shirt pocket. He patted himself down and removed a black object the size of a wallet, which he opened and spoke into.

Eun-ju, the real one, had lush, thick hair, and she looked like any heathy young mother as she cooed to her baby. But when she had crossed the Tumen River three years earlier, she told me, she was nearly bald from malnutrition after subsisting on a diet of grass and shredded bark mixed with an occasional spoonful of rice. She recalled North Korea as a land divided between well-off Workers’ Party members and destitute ordinary citizens. At the time she left, train stations were crowded with homeless people, who sleep in the waiting room seats or on floors crawling with vermin. Eun-ju saw malnourished children stop in their tracks and lie down to die in the streets. Once a wealthy man beat a child to death for stealing food. The government of Kim Jong Il enriched itself reselling the rice donated by the West and Japan. A kilogram cost the equivalent of two months’ wages.

Having no future there, Eun-ju fled to China along with her sister.

“I had no other choice,” she told me. “If I stayed there, I would have died.”

When they arrived in Yanbian, she and her sister placed their fates in the hands of the broker who sold Eun-ju to Young-shik and her sister to another farmer (the broker kept the money). As noisome as the brokers are, North Korean women have little choice but to work with them, and often they are deceived and cross the river without any idea that they are heading for a life as a slave. A woman wandering the countryside alone and begging for bread would be a target for kidnappers. Refugees are on the run, hunted by police and unable to trust anyone. In the case of the poet Jang, he and a friend, also an elite party member, fled the country together, and Pyongyang, enraged at this act of treason by two members of the elite, falsely reported to Beijing that two escaped murderers had crossed into China. Yanbian police launched an all-out manhunt. Several times the men slept outdoors in subzero temperatures Fahrenheit, huddling together for warmth on a mountainside in a blizzard. Even without an all-police bulletin, ordinary economic refugees find it difficult to survive on their own. Fearful villagers report the refugees to the Chinese authorities when they beg for food, Eun-ju told me, and while some Christians help North Koreans, others are too afraid of the police. Park managed to escape North Korea with the help of a church mission that escorted her all the way to the Mongolian border, but Jang and his comrade were cursed and driven off when they approached a church.

A teacher at a North Korean primary school shows off a

A teacher at a North Korean primary school shows off a

Kim-Jong-il calendar. Photo © Yuri Maltsev.

One might think in a market where women are in demand, they would be cherished, but this is not so. An ethnic Korean who is married to a North Korean tells Jang the brokered women are referred to as “pigs.” “In the Chinese countryside,” he says, “pigs are valuable, so people call the women pigs. They’re graded according to their age and appearance.”

Many women are lured to China on pretexts and have no idea sexual slavery awaits them. Jang met a North Korean refugee in Yanbian prefecture who had been sold to a Chinese at fourteen. When she met her buyer, a “middle-aged monster,” he tore off her clothes, she told Jang. She cried because she was frightened. “Then his mother and sister came into the room, those witches,” the girl said. “They held my arms and legs down and pulled my underwear off.” The women pinned the girl down while their son and brother raped her. Some peasants who buy women pimp them out to fellow villagers as prostitutes; other men chain their new wives up during the night so they can’t escape. The U.N. commission states that one woman was lured to China on the pretext of working on a farm but was sold to a man who kept her as a slave for three years. Pregnant, she escaped but was arrested. Police took her to a transit prison, where her jailers raped her and the other women they had rounded up.

Park, who had been forced to eat cicadas and dragonflies, was also deceived. She and her mother fled across the Yalu River in 2007, thinking they could find jobs in China. (Her sister had already crossed over.) The thirteen-year-old Park had recently endured abdominal surgery for a mistaken diagnosis of appendicitis (she woke up screaming in the middle of surgery because the surgeons didn’t have enough anesthetic for her). She weighed only sixty pounds and barely managed to hobble across the frozen river. The Chinese man who met them wanted to rape Park, but her mother offered herself instead, and Park heard her cries outside as he assaulted her. The girl eventually becomes the mistress of a small-time gangster and human trafficker, while her mother is sold to a farmer. He compels Park to help with his trafficking network, selling other North Korean girls who have crossed into China. She gets them cleaned up, buys them clothes, teaches them about hygiene and cosmetics, and helps sell them.

“I didn’t have pity for anyone, including the girls I helped sell, including myself,” Park writes.

At the time I visited the Chinese farmer and his North Korean wife, I wrote that he bought her for three thousand yuan, or just under five hundred U.S. dollars. Jang, who escaped later, writes in Dear Leader that women cost a third of that. Yet Park says women were selling for over two thousand dollars at the time she arrived. It is worth noting that Park was personally involved in the business, unlike Jang and me.

“The first time we met,” Young-shik told me, “the broker said, ‘Do you think she’s OK?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ If you don’t like her, they will find you someone else.”

Those who are handed back to North Korea are considered traitors by the regime. In 1993, the U.N. commission reports, China forcibly repatriated a family, whereupon they were sent to their hometown in North Hamgyong Province. Police forced the entire population to attend a brutal spectacle in which they handcuffed the family, including a five-year-old boy, and paraded them around town. The report states, “The mother and father were then dragged around like oxen with rings that had been rammed into their noses. … The spectators swore at the victims and threw rocks at them.” Nobody knew what became of the family after that.

For her part Eun-ju considered herself lucky to have ended up with a good husband, but the couple had already moved four times to evade the police. She did not know what would happen to her baby if she were deported, but a child conceived in China would not be treated well in North Korea. Carrying their racist ideology to its logical extreme, North Korean officials force pregnant returnees to abort their babies. A woman named Jee Heon A told the U.N. commission that upon her repatriation to North Korea she was jailed with a mother who gave birth. She states:

The baby was crying as it was born; we were so curious, this was the first time we saw a baby being born. So we were watching this baby and we were so happy. But suddenly we heard the footsteps. The security agent came in and this agent of the Bowibu [short for Kukgabowibu, or State Security Department] … told us to put the baby in the water upside down. So the mother was begging. ‘I was told that I would not be able to have the baby, but I actually got lucky and got pregnant so let me keep the baby, please forgive me’, but this agent kept beating this woman, the mother who just gave birth. And the baby, since it was just born, it was just crying. And the mother, with her shaking hands, she picked up the baby and she put the baby face down in the water. The baby stopped crying and we saw this water bubble coming out of the mouth of the baby. And there was an old lady who helped with the labour, she picked up the baby from the bowl of water and left the room quietly.

Even in China, the children of North Korean refugees have limited prospects. Eun-ju’s son was unregistered, and thus would never be allowed to attend school. These offspring of North Koreans in China are known as “dark children,” Jang writes. Often abandoned by their mothers, they beg in the streets. Yet despite the circumstances that joined Eun-ju and Young-shik, they seemed to be content together. After an hour of talking to me, the couple fell silent, gazing timidly at each other, the baby sleeping on her side. Before long it would be dark out. Young-shik and Eun-ju said they were afraid. She did not want to go back; he did not want to lose her.

Min-sik and I got up to leave.

.

Bridges to Nowhere

In 2001 Nonna and I again glimpsed the Hermit Kingdom from China, this time from Dandong, where I had decided to search for stories based on nothing more than a hunch while looking at an atlas. I had to leave Russia temporarily to renew my visa, and I was looking for a city off the beaten track, so it would not be picked clean of stories by the foreign press corps in Beijing (Nonna also wrote for Russian newspapers). Dandong was a seaport, which meant I could find trade-related stories for The New York Times or BusinessWeek, my best-paying publications. And it was located across the Yalu River from North Korea.

My hunch proved to be correct. Dandong had a population of nearly eight hundred thousand, making it a medium-sized provincial town by Chinese standards, but it was the center of a lively trade with the North Korean river city of Sinuiju. Dandong is bustling in the typical go-go Chinese way, with crowds of cars and bicycles on its streets and the skeletons of high-rise hotels wrapped in sheet plastic going up in the city center. From downtown, two bridges extend toward North Korea (a third has been built eight kilometers south). The Broken Bridge reaches only halfway toward the North Korean bank–the rest was destroyed by U.N. bombers during the war–and tourists and gawkers can stroll out to the end and photograph the opposite bank and curse the Imperialist Running Dogs responsible for the destruction. Truck and train traffic crosses the China-North Korea Friendship Bridge, just upstream from the Broken Bridge. Lorries and boxcars haul bags of rice and flour and rolls of linoleum and Tsingdao beer into Korea, along with luxury goods for the elite: fine whiskeys, fashionable clothing, spare parts and windshields for party members’ Cadillacs and other foreign cars, and even ostriches. At some point Kim Jong-il decided that ostrich farms were the solution to his country’s protein deficiency. Pyongyang has been subject to sanctions and is not especially adept at trading with the depraved world, anyway, so imports are often brought through Dandong. Dandong middlemen also repackage North Korean exports (wire coat hangers, seafood) as products of China and ship them elsewhere. Despite sanctions, I was told, American retailers were selling sweaters made in North Korea but labeled in China.

One morning Nonna and I took a walk along the quay beneath the two bridges. Along the waterfront, vendors sell North Korean paraphernalia to Chinese tourists: military-looking decorations, won banknotes, propaganda posters of soldiers smashing G.I.s with rifle butts or saluting Kim Il-sung, books of stamps featuring their leader-god. The Great Leader usually looks slightly to his right, and he flashes the dentured grin of a retiree on a sunny day on the links in Fort Myers. (His son, Kim Jong-il, is credited with hitting eleven holes in one on Pyonyang’s eighteen-hole golf course the first time he picked up a club.) Although I had been told in Vladivostok that no North Korean would ever part with his sacred Kim Il-sung lapel badge, they were easy to buy in Dandong if you are content with the older version, in which the Great Leader stares straight ahead stony-faced. Along the quay a writer for Slate also encountered people in colorful Korean attire, but it seems the Chinese like to rent Korean wedding garb and have their pictures taken with Sinuiju in the background.

Nonna and I bought tickets for a boat tour that crossed the river and hugged the opposite bank in North Korean territorial waters. We were so close I could have sailed a coin into Sinuiju. We passed an empty amusement park with a motionless Ferris wheel. In any normal city, such an embankment would have been a busy place on a clear spring morning. Joggers and dog walkers and young lovers would have been enjoying the sun, ice cream sellers would be hawking popsicles, balloon men selling inflatable Mickey Mouses. But in Sinuiju all we saw were border guards in those oversized Soviet-style hats, looking like skinny schoolboys dressed up in their father’s old uniforms. Upstream, our tour boat chugged past a line of rusty fishing trawlers and a windowless factory over which not a puff of steam rose. Red-lettered slogans decorated the waterfront. Rather than promising death by firing squad to those disobey traffic rules or hoard food, in this place North Korea post more palatable boasts for international consumption:

Long live the son of the 21st century, General Kim Jong Il!

Long live the great military-first politics!

Rich and powerful country

Of all the times I have skirted the border of North Korea, including a trip to the DMZ from Seoul, my most striking view of the country came from Dandong, in a rotating restaurant atop a high rise at night. As we started dinner, our window was facing the Chinese side, and the nighttime city stretched away beneath us in circuit board patterns, aglow with streetlamps and lighted apartment windows and LED signboards and business districts glowing with neon. You chat with a Chinese-Australian couple you met in the hotel business center, order a few local specialties for dinner, and sip a chemical-tasting Chinese wine, talk and laugh, and when you look out the window again, the city has vanished. You’re staring at the frogless void of North Korea.

Across the entire dark city of Sinuiju, with hundreds of thousands of residents, I counted eleven lights. It stayed like that all night; the electricity never came on. Those eleven lights, we were told, marked the location of police stations. I am guessing one or two prominent party members or Bowibu officers also had electricity at home. Immediately below our rotating restaurant were the bridges to nowhere. Even the newer one looked like it had been chopped off halfway across, because the lighting stops mid-river, and North Korea does not have power to illuminate its own side. At the time we were there, Pyongyang was threatening to walk out of reunification talks if Seoul did not provide the North with free electrical power.

North Korean soldiers at the port of Rajin, near the

North Korean soldiers at the port of Rajin, near the

Russian border, in 2014. Photo © Yuri Maltsev.

Back in our hotel room, I flipped through the TV channels to 22 and found myself watching North Korea’s Chosun Joongang network. It was the first time I had seen anything on that channel. For most of the day it is dark: no reruns, no test patterns, nothing but static, but, I discovered, after five every evening, Channel 22 awakens as the voice of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. As I would write in an op-ed for The New York Times, the camera panned a hall full of teenagers: the boys in dark suits, the girls in traditional Korean dresses. Iron-faced, they were watching an awards ceremony. Half of the winners took home red banners extolling the Kims and their kingdom. The rest won red accordions, an instrument that North Korean school teachers are required to master.

Fascinated, I began turning on Channel 22 whenever it was on the air. Chosun Joongang devotes hours to Kim Jong-il’s tours of factories, and perhaps because a collapsed economy has only so many new factories to show off, some of the footage was eleven years old. A narrator with a castrato’s voice spoke in trilling, almost hysterical tones as the Dear Leader made his rounds. Kim Jong-il was a corpulent man with a sallow face, wearing dark glasses indoors. The people he met bowed from the waist. Crowds made fist-clenching salutes and beat their chests, or they waved both hands in the air, jumping in excitement like dogs whose master has returned home after a week out of town. Kim Jong-il’s mind was untroubled by mere curiosity. He was never shown asking a question, but rather lectured the experts, snatching up pointers to jab at wall maps or diagrams. (His son has continued the tradition, offering “field guidance” at farms and military installations and even, recently, a terrapin farm, where, sad to say, all the baby turtles had died. And why did they die? Because there was no food for the animals and no electricity to circulate water into their tanks. Irrelevant. The manager was clearly a saboteur. He was shot.) Oddly, I never heard Kim Jong-il’s voice on TV, only the narrator’s. In one clip, the Dear Leader toured a facility that produces syringes. Did the broadcasters even notice that the managers were wearing coats and astrakhan hats indoors? Or perhaps North Koreans–millions of whom live and work in unheated quarters–consider such details unremarkable. And suddenly the TV showed those ostriches I had heard about, towering birds that twirl and flap, moving Kim Jong-il, it appears, to offer tips on applying the precepts of Marx and Kim Il-sung to the breeding of flightless African birds. Literary content consisted of static shots of the day’s newspapers, page by page, too small to read. And there was children’s fare: a cartoon in which a boy hero was captured by an enemy who looked like a samurai, beaten unconscious, and bound with a stick jammed in his mouth to prevent him from screaming for help.

Most frightening of all was the North Korean idealization of hard labor. While the narrator enthused, thousands of workers strapped boulders to their backs and ran to a dam, where they thumped down the rocks and sprinted back for another load. In close-ups the workers’ faces were frozen in rictus grins, but their eyes revealed a leaden terror. It is as if Stalin thought that broadcasting the construction of the White Sea Canal by gulag laborers would inspire his countrymen. Or maybe Kim Jong-il was happy to put a good scare into his people. In any event, much of North Korean TV might feel familiar to Russians of Stalin’s generation: parades of tanks, goose-stepping soldiers, Soviet-style choruses. But if the programming offers a nation’s most grandiose boasts, consider what its darkest secrets might look like.

That night after Nonna went to bed and North Korean TV flickered back into static, I opened the curtains and stared out our window at the frogless dark. Across the river, the night was all-consuming, making Sinuiju seem like a medieval town. Without artificial light, life settles into pace familiar to our species for most of its existence, with people going to bed after sundown. Perhaps you imagine that during a blackout, you would read by the glow of a fireplace or a candle, like a boy Abraham Lincoln sprawled on a cabin’s plank floor or Caravaggio’s St. Jerome lighted in chiaroscuro with a skull on his desk. But even if you set up four or five candles to bleed wax all over your bedside table, as I used to during blackouts in Russia, the illumination is weak and skittish and you worry you’ll go blind or burn the place down if you nod off. So you give up at eight o’clock on a winter evening and blow out your little bedside Pentecost and allow yourself to drift into the underground river of sleep.

In her book Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea, journalist Barbara Demick tells of North Koreans who actually love the curtained privacy of the dark, when one is shielded from the eyes of tattlers and spies. A young escapee whom Demick calls Mi-ran recalls that she had “tainted blood” because her father had served in the South Korean army, but at twelve years old she fell in love with a boy of fifteen from a privileged caste. She could not be seen in public with him without harming his career prospects or her own reputation for virtue as a North Korean girl. Besides, where would they go? The blackouts had shut down all the cinemas and restaurants. So their dates consisted of walks in the dark. Demick writes:

They would meet after dinner. The girl had instructed her boyfriend not to knock on the front door and risk questions from her family. The boy found a spot behind a wall where nobody would notice him as the light seeped out of the day. He would wait hours for her, maybe two or three. It didn’t matter. The cadence of life is slower in North Korea. Nobody owned a watch.

The girl would emerge just as soon as she could extricate herself. At first, they would walk in silence, then their voices would gradually rise to whispers and then to normal conversational levels as they left the village and relaxed into the night. They maintained an arm’s-length distance from each other until they were sure they wouldn’t be spotted, talking about their families, their classmates, books they had read–whatever the topic, it was endlessly fascinating. Years later, when I asked the girl about the happiest memories of her life, she told me of those nights.

“It took us three years to hold hands,” Mi-ran tells Demick. “Another six to kiss. I would never have dreamt of doing anything more. At the time I left North Korea, I was twenty-six years old and a schoolteacher, but I didn’t know how babies were conceived.”

After her father’s death, she eventually fled North Korea with her mother and siblings, never telling her boyfriend good-bye because no one could be trusted, not even her beloved for the past fourteen years, when it came to crimethink. This hasty departure was the source of great remorse for her, and years later, in her early thirties, married and the mother of a young child, she still longed for him.

The silky black of the night: Jang, the poet-escapee, had his own bizarre tale of a journey that begins in the unlighted streets of Pyongyang. As a young writer in his twenties, he says, he composed an epic poem that delighted Kim Jong-il (you’ll never guess the subject). One night after midnight the phone rings, and the caller tells Jang, “I am issuing an Extraordinary Summons. Report to work by one a.m. Wear a suit. You are not to notify anyone else.” Leaving his parents asleep, Jang puts on his best suit and tie and hops on his bike to pedal into the frogless dark.

Outside, there are no streetlights lit. The silence of the capital city is so absolute that I can only sense the presence of passers-by before their dark shapes loom into my vision. The electricity supply is in a perpetual state of emergency, even though there are two power stations serving the city. … [N]either produces enough power to supply more than one district of the city at a time. So, like a roaming ghost, power settles in rotation on sections of Pyongyang for about four hours a day.

It is not out of the question that the summons might be to his own execution–you never know in the Democratic People’s Republic–but it turns out he is invited to a banquet in a secret palace of Kim Jong-il’s, along with the country’s most senior experts in South Korean affairs, among them army generals and party secretaries. The guests are served fish, meat, wine, a dessert of ice cream soaked in liqueur and set alight. Jang does not specify beyond that, but the Kims’ former Japanese chef reports both the late Kim Jong-il and his corpulent son and heir loved sushi, lobster, Uzbek caviar, Kobe steak, shark fin soup, Cristal champagne. One rare dish was not on the menu: good, old North Korean frog. Nor were field mice, nor snakes and worms, nor nettles, nor cicadas and dragonflies, nor a porridge of pounded pine bark and grass, nor hoarded grains of rice boiled in a watery soup nor bits of undigested corn plucked from animal manure, nor the foul gunk scraped from the cargo holds of freighters that had carried imported rice–none of the foodstuffs the Dear Leader’s subjects were consuming. “We had to eat everything alive, every type of meat that we could find; anything that flew, that crawled on the ground,” one former inmate of Political Prison Camp No. 15 at Yodok told the U.N. commission. “Any grass that grew in the field, we had to eat.”

When Kim Jong-il, seated at his dinner table, summons Jang for the honor of clinking wine glasses with the Dear Leader, the poet scurries over and bows, bent double at the waist. From this position he notices something odd beneath the table. The nation’s leader-god, also known as the General, has removed his shoes. “Even the General suffers the curse of sore feet!” Jang puzzles. “I had always thought him divine, not even needing to use the toilet. That’s what we were taught at school and that’s what the party says: our General’s life is a continuous series of blessed miracles…” Kim’s shoes have high heels and inner lifts at least two inches thick. These, like his permed, oatmeal-drum haircut, are merely means of disguising his height of five foot three inches. Kim uses the coarsest language, muddling subjects and predicates, not the elegant, beautiful speech he does in books. He calls his top leaders not “Comrade” but “You!” and “Boy!” He does reveal an exquisite sense of humor, though. When they meet, he accuses Jang of having plagiarized his poem. “Don’t even think about lying to me,” Kim says. “I’ll have you killed.” Then he chuckles. Haha! Just kidding. A barrel of laughs, Kim Jong-il.

A band performs, fronted by a chanteuse in a white dress. She sings a poignant Russian folk song. Everyone present scrutinizes Kim for his reaction. And guess what! The Dear Leader is moved! He dabs his eyes with a handkerchief, even cries! These generals and senior cadres, among the most powerful men in the country, all pull out their handkerchiefs, and weep in solidarity with their leader-god.

“Can I escape this banquet with my life?” Jang writes. “But before I can think any further, my own eyes feel hot and tears begin to flow down my cheeks. … As I repeat these words, I must cry, I must cry, my tears grow hotter and anguished shouts burst from somewhere deep within me.”

Later, on his way home, now a hero, a member of The Admitted, who has clinked glasses with Kim Jong-il, Jang is disturbed by the memory of the Leader’s emotional outburst. “A distressing thought grips me,” he writes, “and it’s hard to shake off: those were not the tears of a compassionate divinity but, rather, of a desperate man.”

.

Judgment Day

While much has changed in Vladivostok over the years, one constant remains on the labor scene: there is still a market for North Koreans workers doing home repair. There were North Koreans in town when I visited in 2014, and a Facebook contact recently posted in Russian: “Friends! Share phone numbers of our North Korean friends–those who can remodel. Preferably, a foreman who speaks Russian.” When someone challenged him, “Why Koreans?” he answered, “Koreans did an excellent job the previous time. The doors that a Korean installed work excellently. Those that a Russian had installed were lopsided. Also the time it takes, of course. Our guys procrastinate for too long.”

North Korean bricklayer in Vladivostok, Russia. Photo © Valentin Trukhanenko.

North Korean bricklayer in Vladivostok, Russia. Photo © Valentin Trukhanenko.

Shortly after my story on the guest workers ran, a North Korean rang the doorbell of our apartment at dinnertime and introduced himself. Hyo-sik, we’ll call him. He was a scrawny thirty-two-year-old no taller than my stepson Sergei, who was then eleven. In broken Russian he offered his services: painting, remodeling, opening doors in walls between rooms, laying down linoleum–you name it. Given the FSB’s warning about angering Pyongyang, Nonna and I had been watching for any signs of interest in us among North Koreans, and in such a frame of mind, it seemed suspicious that he had suddenly shown up at our place and was without the usual companions. He seemed friendly enough, however, and when Nonna said she had no work for him, he looked so disappointed, she invited him to dinner. He wolfed down a meal of fish and potatoes, asked for seconds.

“At home, there isn’t enough food for everybody,” Hyo-sik said.

When he stood to go, he demonstrated his poverty by poking his fingers through the holes in his trousers. “Do you have any small men’s pants?”

We gave Hyo-sik a pair of Sergei’s jeans. He slipped into Sergei’s bedroom to try them on, then came back out to show us. Ta-da! Perfect fit. Hyo-sik then asked if we had any old videocassettes. We dug out an old one and gave it to him.

In the Soviet era, sailors returning from foreign ports of call used to smuggle forbidden pop LPs and cassettes into the country–the Beatles, Bob Dylan, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, Jethro Tull–and nowadays there is a monument in downtown Vladivostok to these cultural revolutionaries who, simply because they liked the sound of the beat or thought they could make a good capitalist buck off a rare commodity, defied the state and spread the Dionysian message of freedom and sex and rock ’n’ roll. This is happening in North Korea, too. Park recalls how, at her aunt and uncle’s house when she was a child, they would close the curtains and secretly watch smuggled movies on the VCR: Cinderella, Snow White, James Bond. The picture that changed her life, however, was Titanic. She was amazed that in 1912 people had better technology than North Koreans, and it shocked her that anyone could film “such a shameful love story.” In her country the filmmakers would have been executed. No private love was allowed, only love for the Leader.

A poster in a North Korean kindergarten urges

A poster in a North Korean kindergarten urges

students to be quiet. Photo © Yuri Maltsev.

But in Titanic [she writes], the characters talked about love and humanity. I was amazed that Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet were willing to die for love, not just for the regime, as we were. The idea that people could choose their own destinies fascinated me. This pirated Hollywood movie gave me my first small taste of freedom.

Nonna and I liked to imagine we played our own little part in opening the eyes of our neighbors south of the Tumen: the children, the lovers, the sufferers, the hunger artists, the eaters of dragonflies and frogs. We thought of Hyo-sik and his family, like Park’s, drawing the curtains and gathering around the TV to watch the videocassette we gave him. It opens with credits against a deep blue, cloudy sky of the sort Kim Il-Sung might manifest himself in on the day of his Second Coming. Except that this movie would not be the sort his people would want to be caught watching on Judgment Day. It was a love story. It was called Groundhog Day.

—Russell Working

.

Sources

For a discussion of the regime’s understanding of race, see B.R. Myers’ The Cleanest Race: How North Koreans See Themselves and Why It Matters.

Bruce Cumings describes the toll of the U.N. bombing campaign in The Korean War: A History.

The Chosun Ilbo article, “150,000 N. Koreans Sent to Slave Labor Abroad,” ran in the English language edition.

The Dong-a Ilbo reported on the Choi Deok-geun case in an article titled “Russia asked to reinvestigate 1996 murder of SK diplomat.

Robert Neff discusses the memorial stars in his post, “Who Murdered the South Korean Consul and Why?” for The Marmot’s Hole blog.

In Order to Live: A North Korean Girl’s Journey to Freedom, by Yeonmi Park with Maryanne Vollers, was published this year by Penguin Press.

“Death by Firing Squad to Those Who Waste Electricity!”: Jang Jin-sung’s 2014 memoir Dear Leader: My Escape From North Korea tells of the wall slogans and the Corpse Division. Jang is also the source of the report of North Korean arrestees being returned home in coffins.

The U.N.’s Report of the Detailed Findings of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea tells of “unspeakable atrocities” in North Korea.

A Bloomberg article printed in The Economic Times of India (“China’s one-child policy may skew country’s gender ratios”) reports China’s sex ratio as one hundred sixteen to one hundred. China Daily also reports the balance in an article titled, “Chinese men outnumber women by 34 million.”

Ethan Epstein reports seeing people in Korean wedding outfits in Dandong in his article for Slate magazine, “Staring at North Korea.”

In a story titled, “The Staggering Costs of North Korea’s Rocket Launch,” The Wire’s John Hudson discusses North Korea’s willingness to sacrifice international food aid in order to press ahead with its rocket program, despite massive starvation. While he puts the North Korean army’s lower height limit at four-foot-nine, NPR, in a story titled “Hunger Still Haunts North Korea, Citizens Say,” pegs it at two inches shorter.

Peter Foster reported on famine as recently as 2011 in The Daily Telegraph under the headline “North Korea faces famine: ‘Tell the world we are starving.’”

In an article for London’s Daily Mail, John Power, Miwako Ozawa, and Tim Macfarlan discuss the Kims’ culinary tastes.

Journalist Barbara Demick tells Mi-ran’s story in her 2009 book Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea (New York: Spiegel & Grau).

A story in CyberGolf.com, headlined “All-Time Golf Scoring Record Goes with Death of Kim Jong il,” celebrated the Dear Leader’s prowess on the links. The article is undated, but Kim Jong-il died December 17, 2011.

Wired magazine notes that the smuggling of foreign movies continues to this day. In “The Plot to Free North Korea With Smuggled Episodes of ‘Friends,’” Andy Greenberg reported on smugglers who take USBs loaded with American and South Korean films and TV shows into the DPRK.

Russell Working is the Pushcart Prize-winning author of two collections of short fiction: Resurrectionists, which won the Iowa Short Fiction Award, and The Irish Martyr, winner of the University of Notre Dame’s Sullivan Award. His stories and humor have appeared in publications including The Atlantic Monthly,The Paris Review, TriQuarterly Review, Narrative, and Zoetrope: All-Story. A writer living in Oak Park, Ill., he spent five years as a reporter at the ChicagoTribune. His byline has appeared in the New York Times, BusinessWeek, theBoston Globe, the Los Angeles Times, the South China Morning Post,the Japan Times, and dozens of other newspapers and magazines around the world.

.

.

A stunning, moving, & often horrifying piece, wonderfully written. Thank you, Russell.

Jay, thank you so much for your comment.