.

via http://www.osacr.cz/

I TRIPPED ON NEGATIVE SPACE.

I was trying to draw the space between objects; at least half of drawing is letting emptiness define the object. The other half might be looking closely, letting go of your preconceptions of what something is so that you can see what’s actually there. I was trying to see.

This was decades ago, during a disastrous and self-destructive adolescence that had, nevertheless and astonishingly, transported me from a public high school tucked in the far northwest corner of the contiguous United States to Yale University. I had been groomed to be a Math major with a French minor but, being three thousand miles from my childhood home and drunk off my perceived freedom, I decided to major in art.

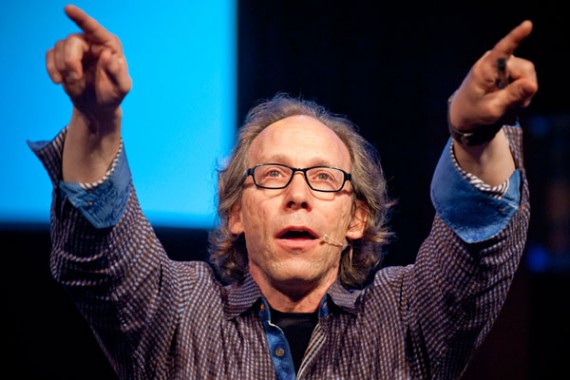

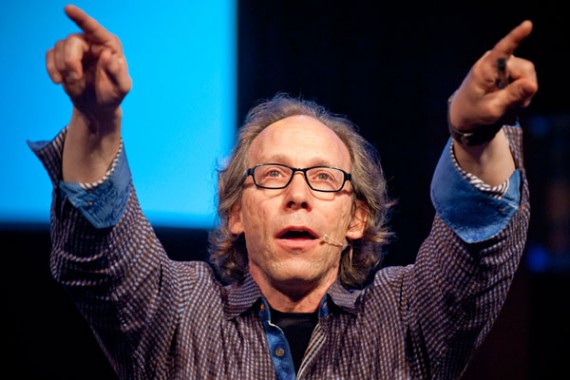

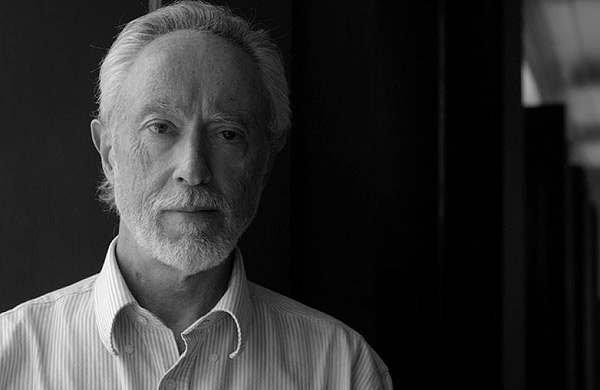

All students were obliged to take some science, to round us out. I took a class designed for non-scientists, one nicknamed Physics for Poets. Lawrence Krauss was my teacher. He was funny and friendly and kind; he didn’t mind talking to bored teens. He was barely out of his own teenage years, though had impressive credentials and a PhD. He looked then much as he looks now: lean, animated, glasses-wearing, short dark hair, a mouth that is crammed with jokes and big ideas.

I was shy; teachers scared me. But Krauss was approachable. He was teaching mind-bending stuff. I’d go to him with questions, and we’d end up talking about nothing.

Because nothing, the physics of it, is his specialty.

I recently contacted him because I wanted to thank the two teachers in college who had helped shape me. One was the drawing teacher who taught me to look at things clearly; I found that he’d died. The other was Krauss. He and I struck up an email conversation, and he agreed to a Skype interview. When we spoke, he’d just returned from Bolivia, where he’d been playing a villain in a Werner Herzog film.

If you search the library shelves for A Guide for the Perplexed, you will find three books: one by Maimonides, the Sephardic astronomer, scholar and philosopher; one by Werner Herzog, the German filmmaker; and one by Krauss.

The universe is filled with unexpected connections. I am a perplexed filmmaker who turns to astrology in moments of desperation. Lawrence Krauss, Phd, cosmologist, is also now an actor.

KRAUSS: I just have to see if this is… Hello? Hello? Hello? Yes? There’s no Mary Lou here. I’m sorry, you have the wrong number. Okay. Okay, okay, okay.

It was from California, and I thought it might be someone that I was… Okay, anyway.

Krauss has been in front of cameras before, talking about particles, dark energy, and God. Now he’s spinning into fiction. And expecting an important call.

ME: Hollywood?

Yes.

KRAUSS: What always has intrigued me, and I think it’s from the time I was a kid, is this connection between science and culture. I am a product of popular culture. When I was a kid, I had a TV in my room, and I would not begin my homework, even from the time I was 10, until The Johnny Carson Show was over, at 1:00 in the morning.

Late night TV, back before cable, would end in static. About 1% of old-fashioned static was caused by radiation emanating from the Big Bang. Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation. Those of us watching TV late at night back before cable, young Krauss, could see traces of our origin.

KRAUSS: It’s hard to be divorced from popular culture, which is what academia is. The books, and then the music, and now the films are another way to engage.

Krauss and I could talk about movies all day, and we spend much of our time doing so, but eventually we get to my agenda. I want to know more about nothing, really. What is it? If I can understand the basic scientific concept, perhaps I can craft a lens through which I can look at other forms of nothing.

I am interested in how what we do not see makes us who we are, how negative space defines us.

Rubin Vase, the classic illustration of space/negative space

Rubin Vase, the classic illustration of space/negative space

§

One of my son’s favorite books is also mine. It is based on a Yiddish song. Joseph had a little overcoat, it got old and worn. So Joseph makes a vest from his overcoat, when that becomes patched and threadbare, he makes a scarf from the vest, then a tie from the scarf, then a button from the tie. Then the button pops off and he loses the button. What is Joseph to do? He makes a story about about the life of his overcoat. The book ends with the moral, you can always make something from nothing.

It’s a great story for writers, facing the blank page.

KRAUSS: The simplest kind of nothing is—which is in fact, I would claim, the nothing of the Bible—is emptiness, is an empty void, space containing nothing, infinite dark. No particles, no radiation, just empty space. But then there’s the kind of nothing which is more deep, which is no space itself and no time itself.

Krauss’s basic thesis, the one that he’s popularly known for, is that the universe could have arisen from nothing. No particles, no radiation, no space, no time. Nothing. Then poof: a universe. A universe as in: everything we can see and measure, a universe filled with energy and stuff. A universe of galaxies and nebulae, gravity and electromagnetism, space and time. A universe of somethings surrounded by nothing, the same kind of nothing there was before the beginning.

We call it nothing because we can’t see it, we don’t understand it, but it is unstable, dynamic. Fertile.

§

ME: Every animal life starts with a Big Bang (one hopes a loving, consensual one). I’m curious about your beginnings.

KRAUSS: Neither of my parents finished high school. My father’s family is from Hungary, my mother’s came from Europe during the war. Jews during the war. Or before the war, actually. I think my parents, being the way they were, and not having been to school, they decided my brother would be a lawyer and I would become a doctor. That was the plan. As a result, my brother did, unfortunately, become a lawyer. A professor of law, actually, which is worse, ’cause they make lawyers. I became interested in science, ’cause my mother made the mistake of telling me that doctors were scientists.

Around high school, I realized that doctors weren’t scientists. In particular, I took a biology course that was just so boring. Memorizing parts of frogs. So I dropped the course, a traumatic experience for me, and more traumatic for my mother, who was still convinced I was gonna become a doctor. When I went to college, I had a motorcycle and I had to get her to fill out some forms for my insurance and send them up to me, and I discovered that she’d written that I was in premedical school, which my university didn’t even have. When I got my first job at Harvard, which was a very fancy position in the Society of Fellows there, my mother phoned up my then-wife, we had just gotten married, and said, “You gotta talk him out of this. What does he want, chalk on his hands? He’d still have time to become a doctor.” Eventually she got over it and is quite happy now.

§

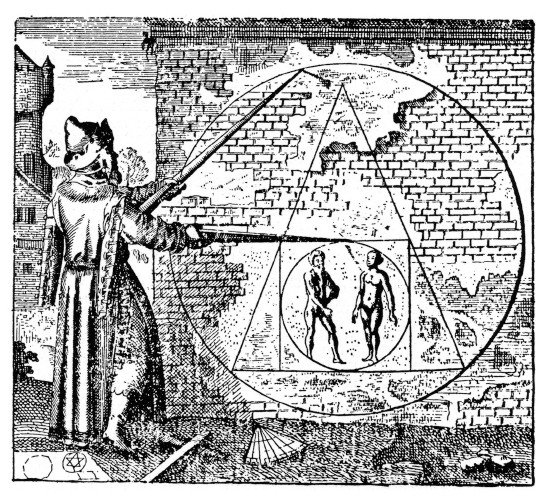

Before my interview with him, I skim books by Krauss, watch his videos. I Google “fields” and “particles” and “quarks” and “quantum.”

What I find is this: everything in the universe is composed of particles. Like numbers, the particles also exist in the negative: anti-matter. Every quark has its anti-quark, every life has its death. The same weight and shape, but in opposite.

Particles interact with fields –gravitational, electromagnetic, nuclear– which are the expression of forces. These forces give the particles mass, and allow the matter to be seen. Fields make particles into matter.

It can be hard to tell where a particle ends and a field begins.

The particles that make up your body come from exploding stars. Krauss has said that the particles that constitute your left hand likely come from a different star than the ones that make up your right. His joke is, Forget Jesus. Stars died so that you might live.

Dying Star via The Telegraph

Dying Star via The Telegraph

§

Krauss talks about God a lot. Rather, he talks about how God wasn’t necessary for the universe to come into being.

ME: How do you define God? Is it as creator? As author?

KRAUSS: As a purposeful creator. As some intelligence guiding the universe. As if you need some design and purpose, and that the universe was created as a conscious act.

ME: Why is it important to you to argue against the existence of God?

KRAUSS: Hold on, my cat is at the door. Hold on. Okay. Okay, cat, you wanna come in? The door is closed, and therefore you wanna come in? Yeah, okay. Okay. Okay. Come here. Come here. There you go. We have a very vocal cat, so—

ME: I can hear her. Or him.

KRAUSS: Him. And he–well, he doesn’t really come in here, but I think the existence of a closed door, which it normally isn’t, and it’s…

ME: The allure of the forbidden.

KRAUSS: Okay. I don’t argue against the existence of God. What I argue against is people’s insistence that their God should impact our understanding of nature and the way we behave. What I argue against is this notion that religion has anything to do with our understanding of the universe, which it doesn’t.

For many people, religion is an obstacle to accepting the wonders of the universe. People should accept the wonders of reality and be inspired by them, spiritually and in every other way. Arguing the universe is made for us is the opposite of humble. I guess part of what my effort is, is to tear down the walls of our self-delusion. Science forces us to acknowledge when we’re wrong. That’s the great thing about science.

What is really remarkable, what we’ve learned in the last 50 years, is that you can create a universe from nothing without violating laws of physics, even the ones we know, much less the ones we don’t know. And that is amazing.

So all I can say is that you don’t need a God. It’s not that it doesn’t exist, but you don’t necessarily need one.

I think a huge problem is that people define themselves as being more than just human beings and they like to be part of in-groups. Religion grows out of tribalism. It doesn’t unify people. It’s designed as us versus them.

Arguing against the necessity of God, arguing for science, it’s political now.

Most of the time people arguing for God are trying to restrict the rights, freedom or livelihood of other people.

§

We used to think that our world existed in a galaxy that was surrounded by an infinity of nothing.

As we refined our optics, stretched our mathematics, poked around in outer space, we found that we are, in fact, not alone. Our galaxy is one of about 400 billion, all spinning, surrounded by empty space.

Nothing is simply what we don’t see, what we can’t see, what we haven’t measured.

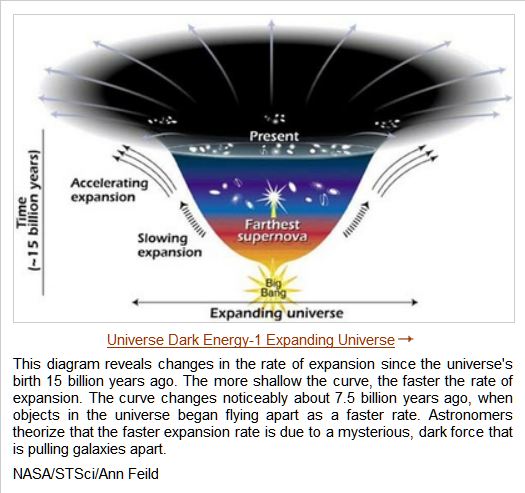

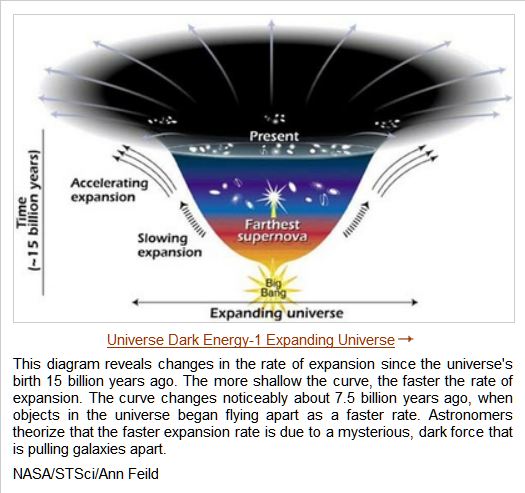

Physicists used to wonder what shape our universe took: was it endless (open), did it loop back on itself (closed), or was it flat (very big, but finite).

The only shape that would allow for the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation to look as it looks is the flat universe.

The flat universe isn’t as bad as it sounds. It is simple and elegant. The total energy in such a place is zero, the positive and negative balance each other out. Light travels in a straight line. It’s not as weird as the other, twisty-turny universes would be.

A flat universe would mathematically require a certain amount of matter. We have measured the mass of everything we can measure in the universe and come up short.

Where is the missing matter?

Where is the matter we didn’t know was missing until we started looking for it?

Turns out, it was nothing.

Nothing is filled with matter and energy that don’t react to the electromagnetic field, it doesn’t emit radiation. It doesn’t shine. So we call it dark.

KRAUSS: We wouldn’t be here, our galaxy wouldn’t be here, if dark matter hadn’t been there. This is the reason that our galaxy was able to form.

Dark matter birthed us.

Dark matter and dark energy are passing through us, undetected, all the time.

Dark matter, dark energy, surround us. We have calculated the amount of darkness, of nothing, and find that it constitutes exactly the amount needed to complement actual matter in a flat universe.

§

There is a great ragged gap in our society. I once thought it was nothing, but now, looking hard, I see that the emptiness is filled with the shape and weight of souls that should be there.

Field notes: Recently, I was upset when I learned about Misty Upham, a woman who lived a couple hour’s drive from my home, outside Seattle. One night, Misty went missing. Despite pleas for help, the police refused to look for her. Despite her movie star status, she was a Native woman living in a community with a history of deep rooted racism. She was found dead, days later, by a tribal search party. It is unclear whether or not she would have died had she been found right away.

Misty Upham was famous, which is why her story made the news. Her story became a lens for others: Indigenous women go missing like this all the time. Native women suffer, disappear, are killed and otherwise violated, at disproportionately high rates.

More raw data: The other day the State Patrol pulled me over for incorrectly passing a slow-moving excavator on the shoulder. I was not shot, I was not taken into police custody, I was not harassed, I was not given ridiculous fines, I was not scared, I wasn’t even nervous. I got off with a warning.

And.

Ours is a time in which black men are killed by police for infractions as minor as mine.

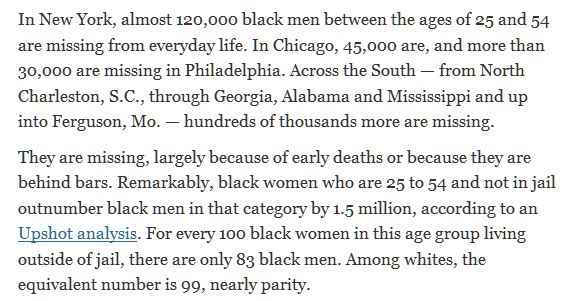

The New York Times recently ran a story about the million and a half black men who are, effectively, missing. Prematurely dead or incarcerated, they are missing from the lives that they should be leading.

From NY Times

From NY Times

§

Gravity, like love, is a force that brings bodies together. Science now suspects that dark energy is the force pushing stars apart, it is the force making our universe flatter.

KRAUSS: Dark energy is much more, much more complex and much more perplexing than dark matter. Understanding the nature of dark energy will inevitably change our picture of virtually everything, because it’s totally inexplicable.

§

The country in which I live, the United States, was founded on the idea of people all being equal, founded on principles of essential human dignity and gravitas, on freedom. It is equally founded on, and made possible by, the erasure and bondage of people.

KRAUSS: My friend Noam Chomsky once said to me, “I don’t care what people think, it’s what they do that matters.” But what people think has an impact on what they do. When you believe crazy things, it causes you to do bad things, or do nonsensical things.

Many of us in this country want to believe that we have left our ugly history locked safely in the past, and have come into the present with our freedom and equality intact.

Missing Indigenous women. Shackled black men. Violent ends. How can we say weare done with genocide and slavery? These unconscionable acts echo through time. They occupy the space around us.

Our society’s deliberate unseeing of the damage done, our willful repression of history, is our dark energy. This is a force pushing people apart, a force that is flattening us.

What we don’t see shapes us.

§

Scientific control: Humans have always killed, colonized, enslaved one another.

Yes. True. But.

This country is a laboratory for how to live with one another, how to reckon with history, how to reckon with difference. We are running an experiment with freedom and equality. If we are to have any measure of success, we can’t do this blindly.

We are starting to see the fields that inform us, that create and support us, the forces of subconscious bias. We are starting to see the violence, the injustice, that we didn’t think was there before.

What has shifted?

In part, is our technology. Our ways of seeing and recording. Dash-cams, body cams, smart phone cameras, everybody can take pictures now. Social media lets loose all this information, all the proof. We can measure, record, and analyze that which has been kept in the dark.

We are refining our optics, our measurements, our ways of communicating.

The Observer Effect: the act of seeing changes what you see.

Ergo: there is hope for us yet.

§

KRAUSS: The universe is a wonderful experiment. We can run data analysis on it. I was using the universe as a particle physics laboratory initially, because the universe allows us to access scales of time and space and energy that we would never be able to recreate in the laboratory.

The universe is a laboratory. It is confined. We can run experiments, and learn about this place in which we live.

My head is a laboratory for my self.

My great-grandfather was an erratic, energetic enthusiast who lit his arm on fire and wound up crippled, who sold insurance, ran a restaurant, made floats for parades, failed as an inventor, established one of the first wilderness areas in the city where I grew up, and regularly appeared in the small town paper because he was the kind of shiny, needy person that attracted attention. Hot dark matter? Charmed particle?

Here is a family secret, something that was long kept from sight: in middle-age, my great-grandfather pilfered a pearl-handled revolver from his daughter, my grandmother, a sharp-shooter.

Bang.

The bullet was a particle shooting through his brain, through his field, warping it. That bullet caused a disturbance in the field of his family. I can point to myself, to my relations, and see ripple effects of his suicide, acts of self-erasure in his descendants: depression, eating disorders, bad relationships.

My great-grandfather was, according to family lore, brilliant and loving and funny, if mercurial. He spawned high-achieving children. He had everything to live for. What dark energy, then, propelled that bullet?

People didn’t know from crazy back then. His name was Art, which kind of slays me.

§

ME: My brain is limited by its neurons, by its chemistry. Aren’t our perceptions, and therefore our theories, always limited by the physical structure of our brains?

KRAUSS: Of course they are. And we have to work with the limitations of our senses and our brains. What science has allowed us to do is extend our senses.

We may be limited, but we know our limitations. That’s one of the great things about science: The limitations are built into the results of science. The fact that there’s uncertainty is an inherent property of science. I’s the only area of human activity where you can actually quantify what you don’t know.

The stories we create are not like religion. The stories we tell are not creations, because we can do experiments.

We have been forced, kicking and screaming, to the physics of the 21st century not because we invented it, but because nature forced us to it. Quantum mechanics led us in directions we never would’ve imagined. Dark energy is another example. No one would’ve proposed that empty space had energy if it didn’t turn out it did.

Art blew his brains out. What dreams, what lies, what loves, what despair splattered out with that gray matter? What exactly did he blow when he blew his mind?

KRAUSS: I tell people that I do physics ’cause it’s easy. It’s just a hell of a lot easier to understand the cosmos than it is to understand consciousness. Physics has hit the low-hanging fruit. The universe is relatively simple, and we are nowhere near understanding the nature of consciousness.

§

I caught my boy the other day with a knife, trying to jimmy open the pistol box we bought after he gleefully downed a bottle of overly sweet children’s acetaminophen, and in which we now lock all medicine. I understand the instinct to open anything that seems shut, to want something sweet, or something that might cure me. I imagine the soul as a box wedged between heart and lungs. I’m trying to pry mine open. It’s messy work, I have an old crowbar. My hands are calloused. I’ve managed a few dents in the lid. Dreams fly out.

Dreams are data from the subconscious. Dark energy, indirectly measured. My therapist analyses the images. For instance, a malignant, alien wind-up toy is a neurotic (malignant) complex that comes from somebody outside myself (alien) to which I give energy or credence (I wind it up). Almost every week, the night before I see my therapist, I will lay a dream as a chicken does an egg. There have been hundreds of dreams and fragments. Alone, they don’t solve anything, but over time, a picture of my subconscious begins to emerge.

By connecting the dreams to my memories of my life to date and to my experience of life right now, by looking at myself as part of a larger family system, by poking around in unpleasant histories, I start to understand some of the darkness that has plagued me. I am freed from wholly blind reaction. It is exhilarating, this embrace of uncertainty, this state of inquiry and perplexity.

The part of the self that seems unknowable, like a black box, like nothing, is –truly– alive, unstable, dynamic. Fertile. That is the self from which dreams and poetry spring.

§

One thing I love about science, about physics, is that it is an attempt at perspicacity. It wants to know the world inside and out, it wants to keep learning the world, forever.

Science, like poetry, traffics in wonder.

We are at a moment in time when we can see, measure, and record information about our universe. In the past, we didn’t have the technology to see far beyond our own edges. In the future, the universe will be so spread out, bodies will be so far apart from one another, there’s no way we’ll be able to see and measure anything other than our own galaxy.

We are at the only moment in time where we can have the picture that we have, tell the story, of ourselves at this moment in time.

Science forces us to acknowledge when we’re wrong, tear down the walls of self-delusion. That’s the great thing about science.

The more evidence we gather, the more we see, the more we change our our story.

What science allows us to do is extend our senses.

What happens when we try to see what we have not seen before? When we try to understand where we come from?

How might a person change, how might a society change, once it starts seeing and contending with its shadow, its missing self?

Understanding the nature of dark energy will inevitably change our picture of virtually everything.

§

As I was writing this essay, I had a dream that I was a teenager looking into the night. The sky was a mess of stars. When I stopped looking so hard, when I looked at a slant, the stars arranged themselves into constellations. Pictures that told stories.

ME: I’d like to check a metaphor.

KRAUSS: Uh-huh?

ME: My understanding is that quarks inside atoms are popping in and out of existence so quickly we can’t see them.

KRAUSS: Yeah.

ME: On a very large scale, is that conceivably what’s true of multiverses as well, is that universes just pop in and pop out and…?

KRAUSS: As far as we know, it’s possible. If gravity is a quantum theory, then universes can spontaneously pop into existence for a very short period of time. Might even be virtual, which means they pop into existence and pop out of existence on a scale so short they could never be measured by any, quote, “external observer.” But other universes can pop into existence and stay in existence, and depending upon the conditions. And as far as I can see, the only ones that could do it for a long time are those that have zero total energy. And it turns out our universe does.

If you wanna replace “God” with “multiverse,” that’s fine. The difference is, multiverse is well-motivated; God isn’t.

It is conceivable that universes pop in and out of existence. Krauss has said that a baby universe might, from the outside, looks like a black hole, but on the inside, be infinite.

The soul might be a black box on the outside, and endless within.

I am trying to figure out how I move through space. I am trying to see the space between people, how that seeming emptiness can shape us. How gravity attracts one to another, how what we don’t see can drive us apart.

We pop in and out of existence, as people, as societies. To an external observer, our lives and civilizations are so fleet as to be virtual.

We spin.

We shine.

KRAUSS: What I like about being human is that there are so many facets to being human.We should enjoy and celebrate all of those facets. What saddens me is that many people live their lives without having any concept of the amazing wonders that science has revealed to us.

ME: Well, it can feel religious in a way, or spiritual.

KRAUSS: It certainly can feel spiritual. Oh, there’s no doubt about it. Oh, yes.

§

A writing teacher once gave me great advice: the end is contained in the beginning.

KRAUSS: It all comes back to our origins. Ultimately what is interesting is: Where do we come from, how did we get here, and where are we going?

Before the beginning, there was nothing.

Something came from nothing; the beginning began.

And this is how we think the universe might end: infinite flatness. Dark energy is driving galaxies apart, stars are accelerating away from each other. Our flat universe is getting flatter all the time. All the protons and neutrons, all the fundamental particles, that make up you, me, energy, space and time, all the laws of nature that govern us, will disintegrate.

Again, we will become ashes, dust. Nothing.

But nothing is fertile.

Something can spring from nothing.

Whirlpool galaxy, Messier Object 51 (M51)

Whirlpool galaxy, Messier Object 51 (M51)

—Julie Trimingham

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

.

NOTES

First: a huge thank you to Professor Krauss. Our lengthy Skype conversation was transcribed; I then took the liberty of editing his responses for length. I also re-contextualized some of those responses, and by no means did I use everything. I am grateful for his playful & creative cooperation.

via www.worldreligionnews.com

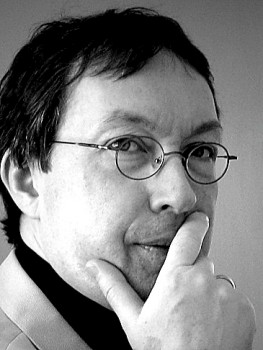

Lawrence M. Krauss, PhD, is a physicist and cosmologist. He has taught widely: Yale, Harvard, Case Western Reserve, Australian National University. He is currently the Foundation Professor of the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University, where he is also director of the Origin Project.

Look for him as the villain in Werner Herzog’s upcoming film, Salt and Fire, to be released sometime in the next year. And then look again: he has a cameo role in London Fields, and may soon be playing other notable malefactors. Hollywood is calling.

The documentary he made with Richard Dawkins, The Unbelievers, is packed with celebrities and good science.

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZxDLkoK8vQQ[/youtube]

Krauss is prolific. All the scientific facts in this essay are derived from his books and lectures. Google his name and you will find a profusion of writings and videos. Those that bear most direct influence on this essay are:

A Universe from Nothing, the YouTube video of a Krauss lecture sponsored by the Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science.

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sbsGYRArH_w[/youtube]

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ovz6tNbBGf0[/youtube]

Other books by Krauss include:

-Atom: A Single Oxygen Atom’s Journey from the Big Bang to Life on Earth…and Beyond

-Beyond Star Trek: From Alien Invasions to the End of Time

-Fear of Physics

-Hiding in the Mirror: The Quest for Alternate Realities, from Plato to String Theory

-Quantum Man: Richard Feynman’s Life in Science

-Quintessence: The Mystery of the Missing Mass

-The Fifth Essence

-The Physics of Star Trek

Join his 165K Twitter followers @LKrauss1. All Krauss, all the time, at https://www.youtube.com/user/LawrenceKrauss.

The tricky thing about blind spots is that it’s hard to know where they are. Tracy Rector (www.clearwaterfilm.org), Nahaan (https://www.facebook.com/TlingitTattoo), and Alicia Roper provided essential readings of, and edits for, this essay. Many thanks to all.

Joseph had a Little Overcoat is Simms Taback’s book based on a Yiddish song.

The writing teacher mentioned in the essay is the magnificent Aritha van Herk.

.

Julie Trimingham is a writer and filmmaker. Her first novel, Mockingbird, was released in 2013. A collection of fictional essays, Way Elsewhere, is forthcoming. She tells stories at The Moth and publishes non-fiction in Numéro Cinq magazine. She is currently drafting her second novel, and is a producer on a film about the Salish Sea. Film and performance clips at www.julietrimingham.com. Julie lives with her husband and young son on a small island.

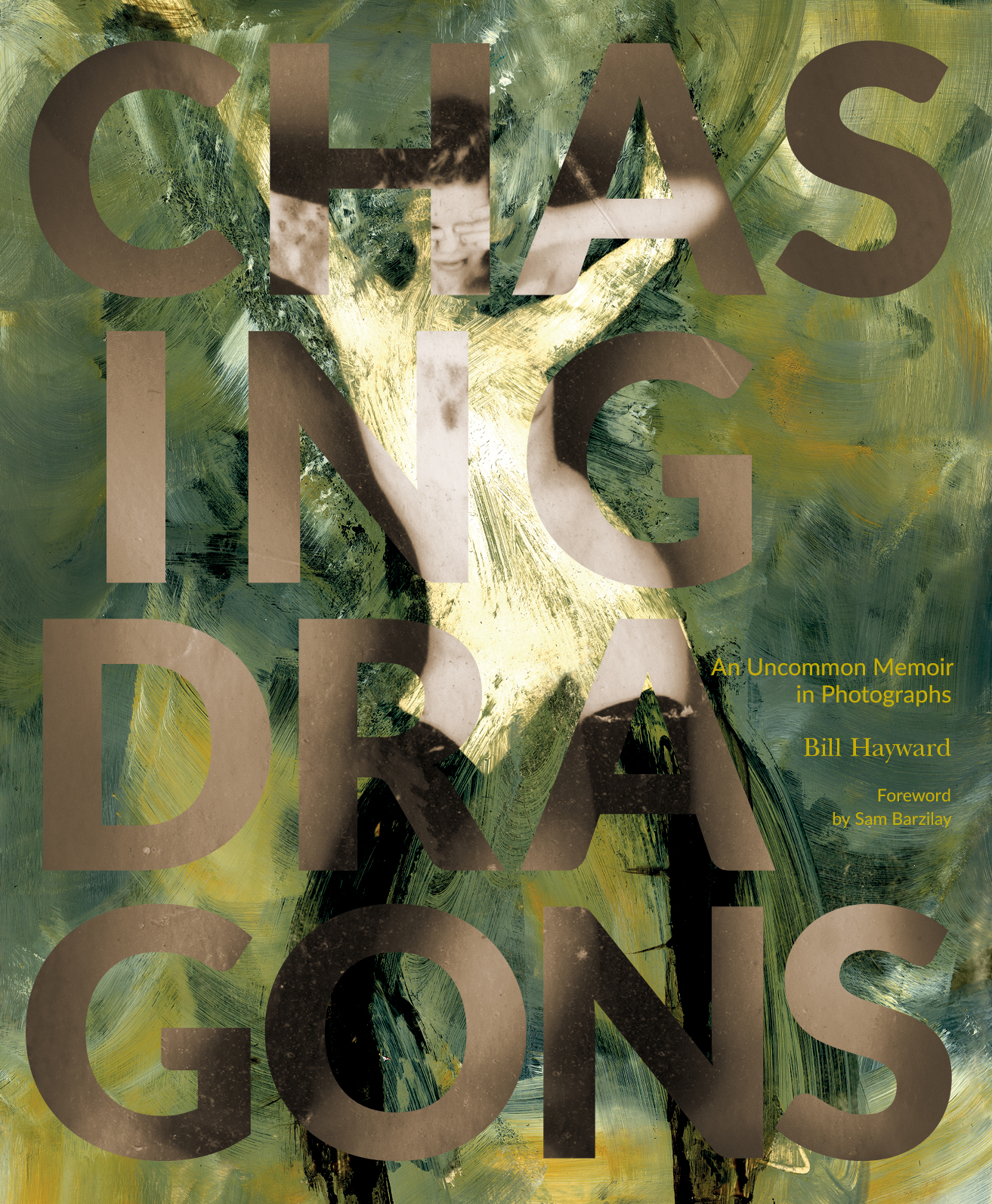

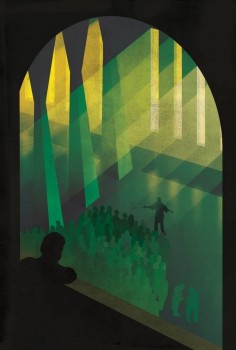

Bill Hayward

Bill Hayward Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan Fragment A (from the film Asphalt, Muscle & Bone)

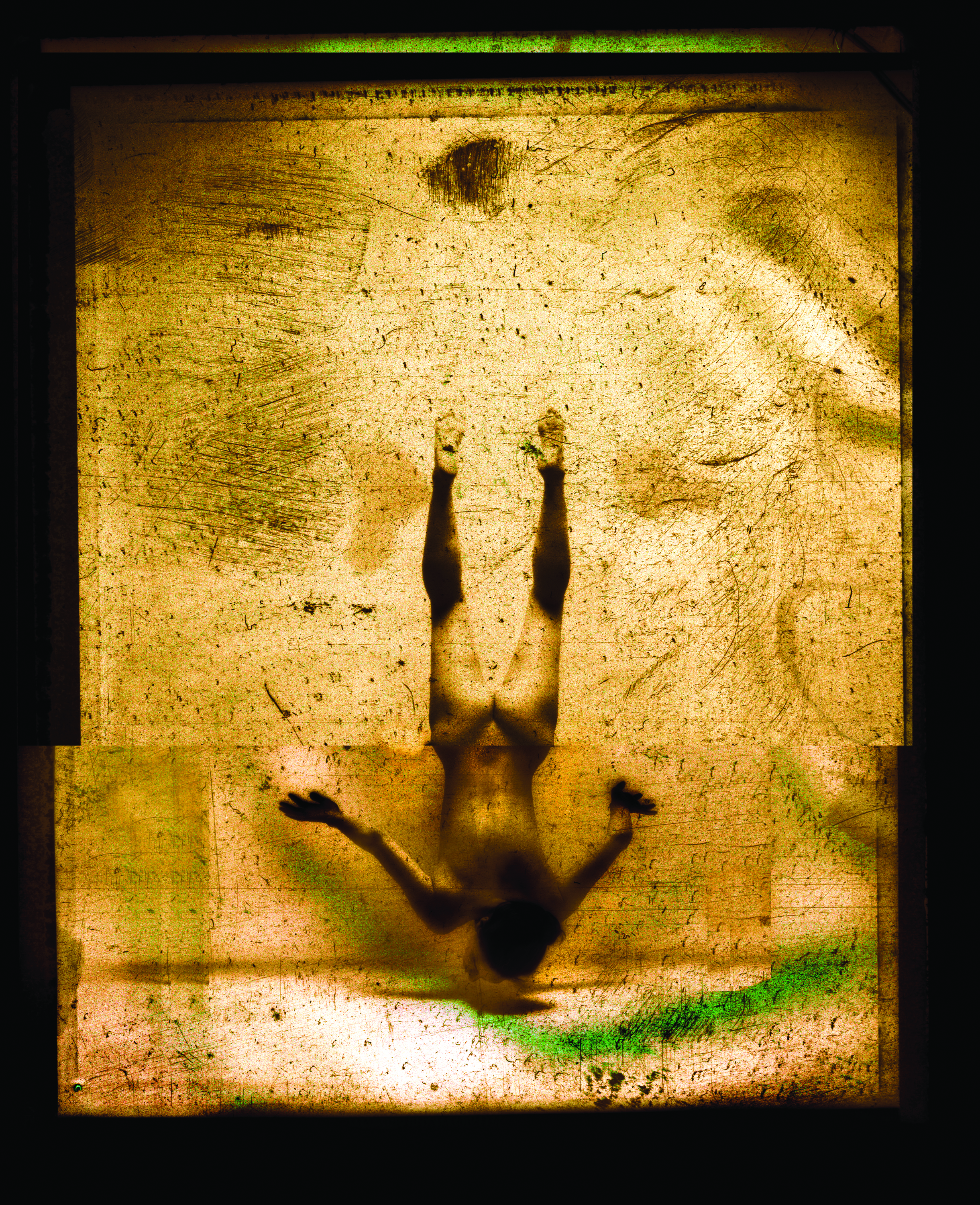

Fragment A (from the film Asphalt, Muscle & Bone) Broken Odalisque

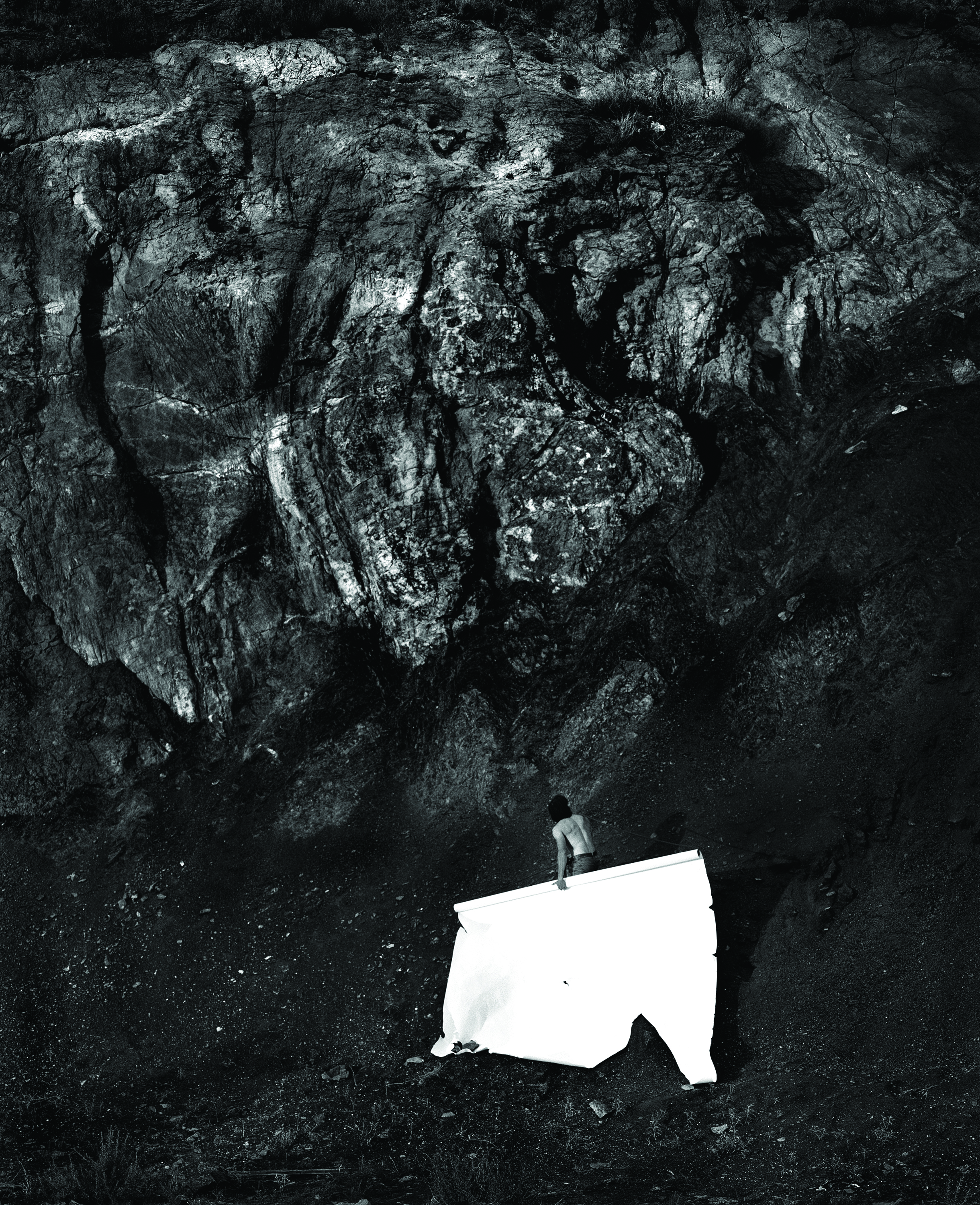

Broken Odalisque Al Pacile (from The Human Bible)

Al Pacile (from The Human Bible) Dragon Smoke Behind Tree

Dragon Smoke Behind Tree

![chaim-soutine-by-Tekkamaki[68597]](http://numerocinqmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/chaim-soutine-by-Tekkamaki68597.jpg)

Whirlpool galaxy,

Whirlpool galaxy,