Janice Galloway via The Scotsman

Janice Galloway via The Scotsman

.

I.In the eponymous story from her most recent collection, Jellyfish, Janice Galloway shows her genius for the ‘ouch’ principle: the wince-inducing collision of something exposed and over-sensitive with something brutal and sadistic.

We feel it coming; harbingers and hints surround Monica and her four-year-old son, on an outing to the beach as a last hurrah, the day before school starts. Alert to the impending separation, Monica sees danger and careless indifference all around her: in the mother who chats to a friend, unaware that her toddler in his buggy hangs over the kerb, too close to the wheels of a passing lorry; in the angry father swearing viciously at his little boy. She worries too much, she wants to protect. Somewhere between the wild beauty of the coast and the unsavoury piles of rubbish dumped by locals, they come across a parliament of stranded jellyfish. Transparent and ‘gummy’, out of their natural environment, one of them is little more than viscous pulp, object of blunt force trauma by human hand. How is the mother to explain this act of random violence on something so exquisitely vulnerable? ‘Maybe they hurt it – her voice faltered – they hurt it just because it can’t stop them.’ Ach, the jellyfish, so hopelessly undefended, not even a skin to mask its insides; the stupid jellyfish, out of its element and asking for trouble. The sight is painful because Monica – and through her eyes, the reader – knows how it feels, recognizes how easily one might end up in its place, how a cherished child might end up in its place. Characters in Galloway’s books are often alive to their inner jellyfish, and aware of – even enduring – the myriad situations in which the hammer may fall.

The recent Guardian review of Jellyfish suggested that these stories held new departures for Galloway in their focus on the parent-child relationship and the natural world. But both make fine provocations for the sort of catastrophic thinking typical to her work; thinking that has flowed and been repressed so many times it creates a carboniferous pragmatism. In the story that intrigued me perhaps the most, Eric Blair (otherwise known as George Orwell), is living with his young son on the Scottish West Coast island of Jura after the death of his wife, Eileen. It’s a hardscrabble existence in a place with no amenities and only the most basic of resources, and Blair is in denial over the diagnosis of his own soon-to-be-fatal tuberculosis. ‘You don’t fight an illness by fighting it; it gives not a hoot about your stoicism,’ the doctor tells him. But Blair is nothing if not stubborn: ‘Rest was not an appropriate response to encroaching lack of breath, lack of power. They had no idea what they were asking.’

Inside his mind, two concerns breed fear; his belief that another war is coming, and his determination to ‘toughen up’ his young son. Excessive fear promotes a formidable fight response, but Blair cannot allow himself anything as weak as emotions; they must harden into ideologies. The story follows his trip to the general stores where he asks whether his parcel – a firearm – has arrived (it hasn’t), and then he begins the twenty mile return trip on his motorbike. The sound of a gunshot from the hills unsettles him so much he comes off the bike, but he’s okay ‘after a fashion’. Menace and machismo shadow box across the pages. He continues hoping for another five years in which to finish his novel and form his son: ‘He’d ruddy well achieve it by means of will alone.’ He was to die less than two years later. But his novel, 1984, the crystallisation of sadism and denial of feeling into a society in which only the broken would survive, lived a dark and splendid life after him.

It’s a fascinating portrait of an artist, from an artist who grew up in what seemed to be a sort of Scottish working-class family microcosm of 1984. Love in the form of brutality, the grim reckoning that the worst would be likely to happen and the best would be to face up to it, deprivation of all kinds, were basic elements of Galloway’s upbringing that transmuted into her writing. But her literary imagination tempers its casual cruelty with tenderness and a cautious optimism. Critics use the word ‘visceral’ a lot, but note the glittering seam of black humour. The New York Times Book Review memorably claimed her work ‘Resembles Tristram Shandy rewritten by Sylvia Plath’, which we might reasonably take to mean that she is an original. Her first novel, The Trick Is To Keep Breathing (1989) won the MIND/Allen Lane award, and was followed by two more novels, two short story collections and, before Jellyfish, two extraordinary memoirs that took the reader deep into the phenomenology of childhood whilst advising caution towards a simple overlap of reality and narrative. There were prizes all around. Not bad for a woman who claimed that an artistic vocation was unimaginable for her as she ‘thought writers were wealthy people who just wrote things out of the goodness of their heart and gave them as gifts.’

II.

Janice Galloway was born in 1955 in Saltcoats, Scotland, to a mother who ‘thought I was the menopause’. In the mythic version Galloway tells in her memoir, This Is Not About Me, which might be the true one for all she knows, her mother was unaware of the pregnancy until her waters broke, perhaps in denial of the freedom-busting, life-ending truth. The young Janice is never in doubt about her status as nuisance. ‘If I’d kent, she’d say, her eyes narrowing. If I’d just bloody known.’ Galloway’s father makes scant appearance in the pages, dying when Janice is only six, though when he’s there, he makes his mark felt. By throwing supper out the back door in a fit of temper, locking Janice inside and making her play chequers with him while her mother is locked out, knocking pitifully on the windows. And finally, setting fire (he was drunk and smoking) to the cigarette stand they owned but had not insured. Just over fifty pages in, she and her mother move into a tiny attic flat above the doctors’ surgery where her mother finds work as a cleaner.

This relative idyll does not last, for Janice’s older sister, Cora, joins them. Cora is seventeen years older and has left behind a husband and son of her own, and once her loud-voiced, gleefully selfish, hard-hitting, pan-sticked presence erupts into the pages, she stalks them like the fifty-foot woman of a B-movie. Galloway calls her Cora, though her real name was Nora, some sort of psychological distance being necessary even in a memoir. Cora takes up all the oxygen in their family and is dangerously jealous if her space, status and rule are in anyway infringed upon. ‘Delight to spite took seconds: there was no middle ground,’ Janice recalls. ‘She’ll be found dead up a close with her stockings around her neck one of these days, my mother said. Too bloody cheeky by half.’

Though it’s Janice whose life seems daily endangered. Cora is ‘handy’, which seems to mean useful for violence. She slaps, punches and headbutts her little sister, locks her in a cupboard, sets fire to her hair. Their mother is too tired and too defeated to intervene, and she loves Cora and cannot escape her thrall. The potency of the daemonic, the Greek concept of an unstoppable force of energy that could be turned either to good or evil, is Cora’s superpower. ‘Even wedged into a chair, Cora charged the air with electricity. Something around her crackled fit to kill flies and drop them at her feet in crispy little packets. I couldn’t take my eyes off her.’ She’s mean, but she’s fearless and vividly sexual. Janice is allowed to watch, enthralled, as Cora paints her face on, pours herself into a too-tight bodice and seamed nylons. A trip to the fair with her is high-octane stuff, all thrills and reckless spending. As Janice staggers dizzily off the walzer, Cora ‘walked in a straight line with her hands on her hips to prove it. Nothing beats me, she said. I could stay on that thing all night and not turn a hair.’ But one minute Jekyll, the next Hyde. When their mother has the chance to work full-time, her concern about Janice being all right alone in the two-bed council flat (they moved back in once her father died) becomes Cora’s decision she won’t get in at all. ‘You give her a key and she’ll let people in. Either that or somebody will take it off her. She can wait in the fresh air. It’s good for her.’

In fact, Janice likes the peace in the garden, and there’s the coal-shed if it rains or snows. Although Galloway would later say in interview with Stuart Kelly that ‘The expectation of brutality used to be a commonplace part of most [Scottish] upbringings’, there is a particularly intense quality of disenfranchisement about young Janice, a too-stark awareness of her lack of value, except as emotional punch-bag. The drama in her small household, ruled by Medusa and the Furies, turns her inward, gives her the obsessive good-girl mentality of someone who knows she does not simply deserve the oxygen she breathes. The memoir displays the close-grained hypervigilant powers of observation that come from the traumatised, or as Gareth McLean in The Guardian puts it, ‘her eye for detail comes from having watched life occur while maintaining not so much a dignified silence as a petrified one.’ We’ve been told from the start that this is not about her, and the key to understanding Janice’s story is to recognise the myriad truths in this statement. Her mother’s suicide attempt, her sister’s disappearance, from which she returns bruised and close-lipped, the screaming rows, all the crucible of disturbing events in which Janice is forged, stem from a history that predates her.

‘Watching their faces as they hurled half-understood insults at each other, the feeling of being in the way while most of it raged over my head was letting something else dawn as well. This wasn’t about me…. This was about Cora and mum; mum and Cora doing something they’d done since Cora left Glasgow behind and turned up at the attic… Longer even than that. Weans, my mother said. As though there had been more than one baby Cora had left behind. If I’m man-daft, where did I learn it? I’ve dealt with my troubles. My troubles. It was always the same in our house. Nothing you knew was solid.’

If the young Janice is obliterated by the emotional warfare carrying on around her (in a way that psychologists would suggest is the basis for most severe neuroses), she finds some comfort in knowing she is not its cause. Her place in the world is formed before she ever entered it, by a cross-hatching of fierce emotional currents, the legacy of ancient events, bitter disappointments and sacrifices, in the lives of those who supposedly care for her. Galloway is clear that there is love, that her own childish spirit, even if oppressed, still finds ways to slip free, but the climate and the conditions in which love and freedom find form are not in her control. This is the reality of all childhoods, but most children feel guilty and responsible anyway. The extreme weather of Galloway’s young life may stunt her growth, but it liberates her perspective.

If This Is Not About Me was about the origins of that ‘ouch’ principle, the collision of Janice’s innocence and vulnerability with her sister’s ruthless violence and her mother’s tough love, the next volume of memoir, All Made Up, is about putting Janice together again from the scraps of self left over after the carnage. As a child, she was good at schoolwork and liked singing. As she becomes an adolescent, music will take an ever greater role in her life. Latin will become an unexpected love. And there will be boys, of course, and inevitably. It’s not that conditions change much – within a couple of pages of the start of the book, Cora has broken her nose. And at the end, when Janice is dressed up in borrowed finery for an evening out with her fiancé, Cora takes one look before launching a plate of stew at her. So no change there, then; but Janice grows into her hardiness, her ability to flourish on very little soil and sunshine, and despite her family’s injunction to cultivate shame and self-doubt. ‘I think it’s part of the Scottish temperament: always waiting for something to cut you down to size,’ she later said in an interview.

The memoir races through the key points once Janice has left home for Glasgow university and a degree in music. Her mother died when she was 26, Cora died of a smoking-related illness in 2000 (and the sisters had barely met since Janice left home). This means that when Galloway sat down to write her memoirs, the main characters of her cast were not breathing over her shoulder. She was aware of writing exactly the sort of truthful account of their living conditions they would have hated, but Galloway had come to understand that old, uncomfortable need to pretend was motivated by working-class shame. When she gave her mother a telephone, she would only speak on it in a Yorkshire accent: ‘Even her voice wasn’t good enough to expose,’ she said. But in all the interviews she gave about her memoirs, Galloway is insistent that the mother and sister who appear within their pages are not direct transpositions: ‘I am a writer. You’re not writing people, you’re writing versions of people that fit into a story version of something universal as well as something ideosyncratic.’ But I have to wonder whether this barrier is not there to protect the dead, but to keep Galloway safe from their ghosts. In an article she wrote in the run-up to the Scottish referendum, she admitted that her sister had tracked her down once she realised she was ‘writing stuff’. ‘She phoned me. How she got my number I haven’t an idea. I recognized the voice immediately, however: if I thought I was It I had another think coming, she said. Do you hear? Pack it in. I felt 11 again and almost wept.

.

III.

Janice Galloway’s first novel, The Trick Is To Keep Breathing, is an unruly narrative of a distressed and disobedient mind. The ironically named Joy Stone is a teacher in her 20s whose chaotic love life has tipped her over the edge of breakdown. The married man she has been living with – enough of a scandal in itself – drowned on a holiday abroad they took together and Joy’s grief is all the more unwieldy for being that of a mistress, socially unrecognized and unpermissable. She lives in Michael’s house (subject to further legal battles) on a sterile estate with poor transport links, while her own jerry-built house is slowly rotting away. Joy has no one to turn to. Her best friend, Marianne, has emigrated to America, her family consists of a sister, Myra, who ‘could just stand and scare me to death.’ Health care professionals are worse than useless. Joy imagines saying to her weary and indifferent GP: ‘Ok, let’s talk straight. You ask me to talk then you look at your watch… Can’t you send me to someone who’s paid to have me waste their time? You don’t know what to do with me but you keep telling me to come back.’ And all the time she is sinking deeper into bulimia and depression. She is the prototype jellyfish; a quivering wreck of exposed nerve endings.

Or you could read her as a 20th century version of Job, a woman crumbling under an onslaught of calamities specific to being an abandoned Scottish woman in the late 1980s in poor mental health. This is not a story that begs our sympathy, though, despite the rigors of Joy’s plight. Her exquisite vulnerability, which we readers are invited to witness as intimately as possible, from a ringside seat within Joy’s psyche, is played out on the page as an innovative typographical display that’s entirely distracting. There’s a cordon around Joy’s pain that comes from her own lack of lack of sympathy towards herself and the velvety-black humour that springs irascibly from her narration, as well as the experimental features of the text, attention-grabbing features of a verbal energy that ricochets around the pages, out of control, the underside of a too-tightly held persona masking inner collapse.

‘o yes

when I was good I was very very good but

but

there was more going on below the surface.

There always is.’

In the fragmentary text, words jump out from unexpected places and bleed into the margins, sentences trail unfinished, white space marks missing time and emotional dislocation, italics indicate the presence of memories that remain unintegrated. There’s no order to the story, and no neat boundaries either in the form of orthodox chapter divisions or quotations marks around speech. There’s just an uneven torrent of words acting out, or else a parodic inclusion of conventions: play scripts, for instance, marking cliched conversations, lists, excerpts from magazines spouting cultural commonplaces, and marching imposingly across the narrative, the dreaded mantras of mental health:

The More Something Hurts, the More it can Teach Me…

I write:

…..Persistence is the Only Thing That Works.

I forgot to write:

…..Beware of the Maxim.

…..Neat Phrases hide Hard Work.

…..Everything Worth Having is Hard as Nails.’

A beautifully unarticulated paradox rises up from all this verbal play, in which the insufficiency of such mantras is almost insulting in comparison to the depth of Joy’s disorientation and pain. But such inadequate linguistic supports are all that exist as a bridge back to normal life. Galloway is nothing if not respectful to the reality of her protagonist’s state, and little is resolved by the end of the narrative. But there are the earliest hints of healing; tiny shards of optimism that stud the conclusion with welcome precursors of light.

Talking of cautious optimism, her second novel proved that her characters were at least ready to risk travelling abroad again. In Foreign Parts (1994), Rona and Cassie are friends of long-standing, and mildly mismatched travelling companions who have come to spend their precious fortnight off work in France. Short of cash and feeling unworthy of culture, they know ‘that proper holidays are for proper people with proper money and that real travellers, in denim bermudas of uneven leg length, travel to real faraway places in search of real poor people enduring real life in the raw. We are neither real nor proper: just fraudulent moochers in other people’s territory, getting by on the cheap.’ Cassie, source of the narrative voice though it floats, according to Cassie’s mood, between first, third and even second person, is sensitive, observant, moody and questing for something real and meaningful. Rona is stolid, calm, accepting and happy to tick the vacational boxes. Their differences come to a crunch mostly over the guidebook they have brought with them, entitled ‘Potted France’, whose injunctions to notice historical features enrage Cassie with their vapidity.

Threaded in between the stages of their journey are descriptions of photographs from holidays Cassie has taken with boyfriends in the past and the memories they evoke. Not that these holidays have been any better than the one Cassie is currently on. Holidays fall into a similar category to horoscopes, magazine articles and self-help books for Janice Galloway’s main characters: they are places where the commonplace fantasy of achieving something splendid cracks under the weight of recalcitrant reality. Rona, Cassie tells us, at times when they are sleeping in the car, or in some terrible 50 franc-a-night dive, ‘loves games of not admitting hellishness is hellish.’ But Cassie, like Joy Stone, is in no mood to pretend. And more than that, there is an unspoken but deep-rooted belief in both books that anything revelatory, real, valuable or significant, can only come from an unflinching scrutiny of the situation. When Cassie does transcend the ordeal of pointlessness that is tourism – in Chartres cathedral, playing house in a gîte they hire, standing on the beach at Veulettes before taking the ferry home – these moments have a full-bodied poetry about them that can only come from patient attendance on the authentic.

As such, this is a novel wilfully rejecting a number of conventions; it is not the buddy road trip or travel novel that we might be expecting. Cassie’s sharp edges puncture any such glib journeying. More confusing to its readers (if Goodreads reviews are any indication) is Cassie’s conclusion as the end of the trip nears, that she is no longer interested in a heterosexual relationship, but considering the possibility of moving in with Rona. Cassie and Rona may squabble and bicker, but there is a mutual understanding and recognition between them that is missing, as far as Cassie is concerned, from a relationship with a man: ‘They don’t have the same priorities, to be able to organise their priorities in a compatible way with ours,’ she explains. Cultural fantasy rears its head again, to be cut down to size: ‘The knight on a white charger is never going to come, Rona. You know why? Because he’s down the pub with the other white knights, that’s why.’ If there are generalisations going on here, then they belong to a Scottish culture that lags behind the times (‘There are real gender problems in my country,’ Galloway said once in interview). But what Cassie wants is something free from all sexual and domestic norms. The life she envisages with Rona has no recognisable, culturally-approved shape, resists all labels and orthodoxies.

Right at the start of the book, the first sign Cassie and Rona see when they get off the ferry says: BRICOLAGE. This is a common sign in France, indicating a D.I.Y. store, but its original meaning is one of Heath Robinson-type construction, using bits and pieces of other things to create something new. For this reason it was borrowed by the nouveaux romanciers in the 50s and 60s to describe a kind of literary experimentalism that took apart the nuts and bolts of narratives and put the pieces back together in innovative ways. It stands as a fine sign to hang across Foreign Parts, too, in which the patchwork of travel guides, lists, overheard conversations, street signs, flashbacks and letters correspond at a technical level to the unorthodox ways of experiencing travel and building relationships that are its themes. The disparate and the heterogeneous are more playful, less threatening than in Trick, the anxiety and anger about a dissatisfying present are soothed in this novel into something forward-looking and hopeful.

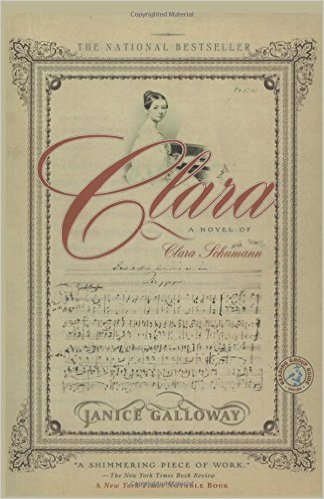

Galloway’s third novel, Clara (2002), was in some respects a departure, a long, lyrical account of the life of Clara Schumann, child prodigy, world-famous concert pianist and composer. Clara passes from the tyrannical hands of an overbearing father, a piano teacher whose love for her resides in her responsiveness to his teaching and who basks in her reflected glory, to those of her husband, Robert Schumann, mad, melancholy, ambitious in his own right and unequal to tolerating a more famous and successful wife. It’s essentially a study of the discipline, the strategems and the sacrifices a woman like Clara must make in order to stay in touch with her musical creativity. Concerns about gender, freedom and madness abound, tethered to historical and biographical realities.

There is still experimentation, but what’s intriguing is that it is so seamlessly incorporated into the narrative it’s oddly harmonious, rather than disruptive. There are phrases from musical scores, poems, lists (of course) and the use of different font sizes. The latter are easy to decode, for they range from the huge beetling-black words of fortissimo, to the smaller fonts of diminuendo. Lists are staccato, poetry is cantabile, all is effortlessly woven into a smoothly flowing, wordy andante narrative. The voice nimbly skips between the heads of Clara, her father and her husband, able to pick up on a wide variety of moods, constantly singing.

In her interview with Stuart Kelly, Galloway denies that her use of experimentation in the early novels was ‘politically motivated’, saying instead that she ‘just didn’t know how to write a story’. Whispering in her ear, perhaps, was the shade of her sister, telling her that if she thought she was It she should just pack it in. The experimentation, in all probability instinctual, reveals a sophisticated understanding of the landscape of the mind when functioning in a state of extreme fear, duress, or misery. Those fragmented, discontinuous texts showed how words could perch unabsorbed upon the mind’s surface, how other voices within might be heckling from the sidelines, how memories repeatedly broke through any stable crust in the present with unwelcome or alien messages. But over the years there is a distinct progression in Galloway’s novels, one that has the appearance, not of anything as facile as healing, but of steady incorporation, acceptance of the ‘hellishness’ for what it is, a breaking down of old parts in order to put them together again, economically, in something new. After Clara came her memoirs, her darkest and her funniest works, the most revealing and the most accessible. Galloway had always been a formidably innovative storyteller; now the novelty was that the story could tell itself straight.

.

IV.

In the final tale in Jellyfish, ‘distance’, Martha is all alone on a trip to Jura, site of George Orwell’s last days. Many years ago now, when she was an insecure young mother, her small son cut his head open on a glass table and the accident unleashed some reckoning with the arbitrary and inevitable nature of catastrophe that has never been resolved. Her solution back then was to divorce her husband and allow him custody, afraid that her own fears would prove contaminatory to her child. Since then, Martha has cut herself off, taking only supply teaching work so she should never be lulled into the responsibility of relationships. Though the invisibility begins to tell. Attempting to teach Orwell to a class of resistant children, she tells them about the time he saved his four-year-old son from drowning in a sailing incident. ‘Sometimes, she said, there’s more to people than meets the eye. Repressed and paranoid and dying is not a whole picture of anyone.’

And maybe Martha is dying; in her forties now, with an burgeoning disease that is gynacological, possibly serious, possibly not, she decides to take this solo trip to Jura. The freedom feels easeful, at night watching the waves she understands: ‘There was no hidden code, no message, no meaning. What happened out there was random, wholly without blame or favour. In the end, nothing hinged on human decisions, nothing demanded retribution or just deserts: what happened was just what happened.’ Then, driving back to her lodgings in the darkness, listening on the car radio to Mozart’s Queen of the Night, she runs over a deer. Martha staggers over to the beast, longing to comfort it, afraid her touch will terrify it further. ‘Dislocated bars of Mozart were gusting like feathers in the night air,’ as she tends to the animal and her own relentless blundering in the world. ‘I’m here, she said, her words bouncing off the surrounding rocks and rising, furious, into the solid dark. I’m here. I’m here.’

And here Galloway’s voice remains, holding fast to its lament of risk and vulnerability, innocence and brutality that cannot be resolved. Instead, the elements are left suspended in uneasy harmony together, awaiting conclusion, a perfect augmented chord.

—Victoria Best

.

Victoria Best taught at St John’s College, Cambridge for 13 years. Her books include: Critical Subjectivities; Identity and Narrative in the work of Colette and Marguerite Duras (2000), An Introduction to Twentieth Century French Literature (2002) and, with Martin Crowley, The New Pornographies; Explicit Sex in Recent French Fiction and Film (2007). A freelance writer since 2012, she has published essays in Cerise Press and Open Letters Monthly and is currently writing a book on crisis and creativity. She is also co-editor of the quarterly review magazine Shiny New Books (http://shinynewbooks.co.uk).