…in the end the strength of the writing itself is like magic, few authors can pull this off, and the final impression is absolute: Italy – dry, beautiful, graffiti strewn, tourist ridden, sexy, fake – and the narrator – lost, bored, amused, searching, lustful – are far too complementary and this is no haven for lost souls seeking redemption, and no one will be rescued from firestorms of ash and lava. —Lee D. Thompson

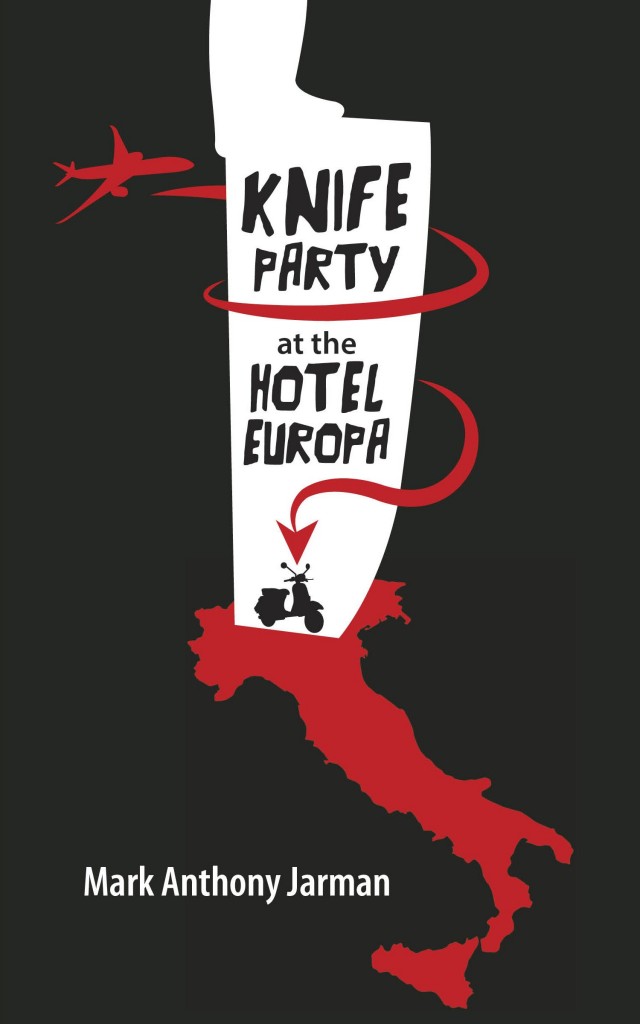

Knife Party at the Hotel Europa

Mark Anthony Jarman

Goose Lane Editions

HC 285pp.; $29.95

.

The twelve short stories in Mark Anthony Jarman’s fifth collection, Knife Party at the Hotel Europa, form a strange, wandering, quite aimless narrative that runs throughout the book. I almost wrote “throughout the novel,” because by a third of the way in, as characters and settings reappear, it begins to feel like a novel, though not a typical novel. The sections do work as short fiction, and Jarman, one of Canada’s most-respected short story writers, is no stranger to the form, and the stories here have all appeared separately in journals or online. So, is this a story collection, or a novel? Well, it’s a bit of both, really, and it also feels like a travelogue, though this is no Fodor’s Guide to Italy.

Not that I think it’s important what category Knife Party at the Hotel Europa fits into. This lack of definition is part of the appeal and likely Jarman’s design.

As is the aimless narrative, the wandering narrator.

This narrator, who is never named, this I in Italy, is in turns all mind, and all… cock. Can I say that? Well, I already have. He is on a vacation, or in exile (it’s hard to tell), renting an apartment in Italy, where there is something he is trying to forget (so says a gypsy woman). He’s down, he’s dour, he has unconvincing thoughts of snuffing himself, but he’s invited to join an ‘art group,’ a tour run by one Father Silas, who owns an illegal art school in Italy and is a friend of the narrator’s aunt. The nature of the art group or school is never really specified (but you’re in Italy, so there’s art, and there are tours), but does act is a kind of binding thread to the collection, as do the few recurring characters on the tour. We never get to know Father Silas, or Ray-Ray, or Tamika much, or the narrator’s dear aunt, but we need bearings, even if the actual viewing of art seems of little importance to the narrator (but he catches on, follows, drifts away). Adding to the man-adrift theme is the narrator’s current life-mess: he’s middle-aged, in existential crisis, separated/divorced from his wife, reeling from the loss of an all-consuming affair with Natasha (who had cancer, but also left him), and suffering a general lack of direction.

The book’s themes are ones of wandering, of gypsies, tinkers.

And decay, and false idols.

It’s a dense, rich book, but the opening story, “The Dark Brain of Prayer”, hides little:

My tainted life, my travels: vaguely free to travel to Italy, Ireland, Death Valley, to ski distant peaks on a whim, mobile, but always a trade-off, no stable home life, no one to depend on. Perhaps because no one can depend on me?

A strong story in its own right, “The Dark Brain of Prayer” also serves to situate the reader in the narrator’s life. We see that he’s Canadian, lives in a city with streets called Queen and King and travels to towns with names like Sackville. These touches serve to keep us close to the narrator, who, like Jarman, appears to live in Fredericton, New Brunswick, a city of flooding rivers, fiddleheads, and crab-apple blossoms.

“Butterfly on a Mountain” follows. It’s meditative, mostly plotless, meandering, funny. And, importantly, we meet Eve. She’s all old world temptation to his new world snake.

Eve is the narrator’s cousin, though their relationship is never explained beyond that, she lives in Switzerland and she comes in and out of the stories (in the recursive Eve entries and with the occasional return also of Natasha we can see how the collection has been purposefully linked, though it’s not quite a novel, but right, that’s not important), meeting up with the narrator, and they stray from the tour, and she, inevitably, becomes his lover (but there’s no sin here, sin in their minds having been worn to rubble like ruins in Rome). Eve is well drawn, sophisticated, educated, unpredictable. The narrator can never get to know Eve, he muses, just as he can never get to know Italy. But he is, once again, infatuated, and Jarman’s stunning prose captures it all.

The bone-green air between the tree trunks, the green shadows between the trunks; who owns that property? I feel Eve owns any part of the world where my eye strays.

Introduced to Eve, we come to the book’s glittering gem, the harrowing, surreal, and utterly believable story “Knife Party”, a nightmarish, drug-induced excursion to a party of strangers, of cocaine and Italian testosterone and a crazed neighbor with a staple gun. There’s a menace throughout the story, and as the title lets us know, it won’t end well, but Jarman’s ability to introduce both humour (“I want to start a new dance craze […] do the Lazy Lawyer, do the Dee-vor-cee dividing his assets into shekels.”) and suspense (“The neighbour makes it to the door, but falls in the hall like a Doric column. He has bled out. […] Spying blood and a body, the woman dials her silver phone, whispers, Madonna save us.”) gives the story a gory, car-crash appeal. We can’t turn away; it’s too lurid, too new. Too life affirming? A strange thought, but in the quieter, meditative story that follows, “Hospital Island (Wild Thing)”, a retreat to Rome, the narrator does feel this trauma has somehow lessened the impact of the loss of Natasha, providing “gruesome perspective,” he says.

But disaster now follows the narrator and Eve, as if they’ve been cursed in their journey (in fact, the narrator is cursed by a gypsy woman in the opening story, though he complains that her curse is far too unspecific to be believable). They flee the knife party into the night, only to stray into the next story, another of the book’s highlights. “Adam and Eve Saved from Drowning” is a story that muses on Canadian soldiers and tanks in World War II rolling through Italy, on a dear uncle killed in battle in Ortona, and where our less-than-adamant narrator and his Eve stroll upon a Roman explosion, a mail bomb at an embassy and man’s lost hand, and where, later, a brilliant day of sea kayaking leads to a small cove and men fishing men from the sea, fishing drowned boat people, migrants to a country that allows so many migrants, yet seemingly welcomes none. The bodies are lain upon the shore:

Men with mustaches and suitcases with wet sand glued to their black coats; this crescent beach was not their destination, but now they are stopped on the sand, their mouths stopped, now they are at their destination. Their skiff sank in riptides, and long lines of spray, their hands let go and their mouths let in sea and sky.

This is a turning point. At the end of the story, Eve leaves at handwritten note under his door while he’s away, writing that while the thought of never seeing him again is intolerable, it might be best. “You do make me happy, but I can’t seem to feel calm.” The narrator then muses:

Eve said I was detached, difficult, maddeningly stubborn.

I thought I was easygoing.

It’s this introspection that gives the book much of its uncanny appeal. Do we even like the narrator? Yes, we do; everyone does. Throughout Knife Party at the Hotel Europa we see a mind at work, a mind that’s endlessly male, musing, heat-addled, a mind made vivid through Jarman’s jazzy, poetic, associative prose. We see his mind’s inner workings, the intimate thoughts, the fantasies, the reveries, the trivia. In a book of travels, Jarman often goes farther afield in his head than on the map, and the book at times takes on the feeling of a confessional stall.

Take, for example, the final section/story, “The Pompeii Book of the Dead”, a near novella-length story that for all its surreal touches, has the feeling of non-fiction, but it’s as if Orwell, before writing one of his book of travels, came across a clump of peyote and found narrative liberation. When approached by a prostitute in Pompeii (at a cafe called Irish Times), the narrator muses:

I flirt with the Croatian maid, I flirt with the cryptic Spanish woman, I stare at my cousin’s form, I stare at every waitress. Then a woman and I share a tiny table in Italy, in Europe, on the planet, and for a handful of Euros I can do certain things for a certain time. How perfect it no longer seems.

There is a young American traveler, an attractive Iraqi refugee, there are women at every corner, in every dream. But Jarman, before getting too deep in his narrator’s self analysis, pulls us into a surreal section involving the narrator and several small statues (come alive from his apartment windowsill and which include a distractingly priapic Priapus) and sends us prowling the alleyways for deep-fryer grease with this ridiculous gang of lard thieves:

The Italian PM must pay his estranged wife a hundred thousand Euros a day; how can he have that much and we don’t? The grease in our alley reeks. Lewd Priapus is with us, but he is not doing well, is not popular, his huge phallus gets in the way of lugging the sloppy plastic drums.

Why does this work? Why can certain writers lead us down a path of folly and not lose our interest? There’s something always on the cusp with Jarman’s fiction, beauty quickly turns to horror, play turns tragic, reality loses all meaning, and we accept that this world, his world, is unstable. It makes for thrilling reading.

In this final story, a masterpiece of pacing, tension, and setting, we also have Jarman’s most haunting touch, the narrator’s observation of a young Italian couple in love. They could have been plucked off a postcard, or tourism billboard. He observes their tenderness, their perfectness as they lie on a bench above a cliff, and wonders if anyone (Natasha) had ever been as tender with him. But he forewarns us, tells us they will die when his tour bus collides with their scooter along the Amalfi Coast. When the scene comes pages later we still hope for another outcome. Surely he won’t? But the young lovers die horribly, almost tragicomically. Jarman seems to be saying there is no postcard Italy, just as there is no postcard love, everything is throwing itself into the sea.

So Knife Party at the Hotel Europa is not a novel with a happy conclusion, and it shouldn’t have one. The narrator does appear to have learned something about himself, but it’s a vague, sloppy realisation. He is who he is.

Does the book have flaws? At times Jarman’s riffing may be predictable (not in what’s written, but that it’s coming), something that works for an individual story can seem repetitive after 285 pages. The tendency to go off on tangents till reason falls off a cliff, or add an absurd third thing to a previously serious list, might wear on a reader. But in the end the strength of the writing itself is like magic, few authors can pull this off, and the final impression is absolute: Italy – dry, beautiful, graffiti strewn, tourist ridden, sexy, fake – and the narrator – lost, bored, amused, searching, lustful – are far too complementary and this is no haven for lost souls seeking redemption, and no one will be rescued from firestorms of ash and lava. Like Pliny the Elder rowing to Pompeii, there’s not much he can do to save the situation, but it’s quite the spectacle and well worth watching.

—Lee D. Thompson.

.

Lee D. Thompson was born and raised in Moncton, New Brunswick. His fiction has been published in four anthologies, including Random House’s Victory Meat, New Fiction from Atlantic Canada and Vagrant Press’s The Vagrant Revue of New Fiction, and in more than a dozen literary journals across Canada and the US. Lee’s first novel, S. a novel in [xxx] dreams, was published in 2008 by Broken Jaw Press. An e-book, Diary of a Fluky Kid, appeared with Fierce Ink Press in February 2014. In addition to writing fiction, Lee is a guitarist and songwriter who records under the name Pipher..

.