[vimeo width=”500″ height=”375″]https://vimeo.com/96516643[/vimeo]

.

In the short animated film “The Approximate Present,” Filippo Baraccani juxtaposes journeys across impressionistic landscapes with an etch-a-sketch rendering of chaos and its patterns. The impressionistic landscapes appear in a repeated visual narrative where we pass over them on a sunny day and then with stormy weather, illustrating how weather alters our emotional and psychological experience. This intense personal experience of landscapes stands in stark contrast to the measured, diagrammatic, and decidedly non-impressionistic illustration of the patterns of chaos as it unfolds in black and white. As the lines progress, it is as if NASA with all its scientific authority has mapped the trajectory of our emotions. Despite this authority and clarity, the graph ultimately cannot triumph over the beauty of the landscapes. Like the man who dies from beauty at the beginning of Paulo Sorrentino’s The Grand Beauty, Baraccani positions the short film’s spectator to swoon at the limits of the self, troubled between the self and beauteous landscapes, gripped by something akin to awe or wonder.

For this short, Baraccani chooses a simple, retro animation. As he notes, “I knew from the outset that I wanted it to be stylized, minimal and solid (for lack of a better term), somewhat reminiscent of early flight simulators. At the same time, I strived to convey a certain sense of place and emotion, drawing inspiration from my own experiences of various weather phenomena.” This might seem counter-intuitive, choosing low resolution graphics resembling something as utilitarian as a flight simulator to render landscapes, let alone to present them as an experiment in the kind of emotional landscapes Baraccani seeks. Yet here the blocky animation renders emotional what would have, in a calendar-like photo realism, been beautiful but perhaps not moving.

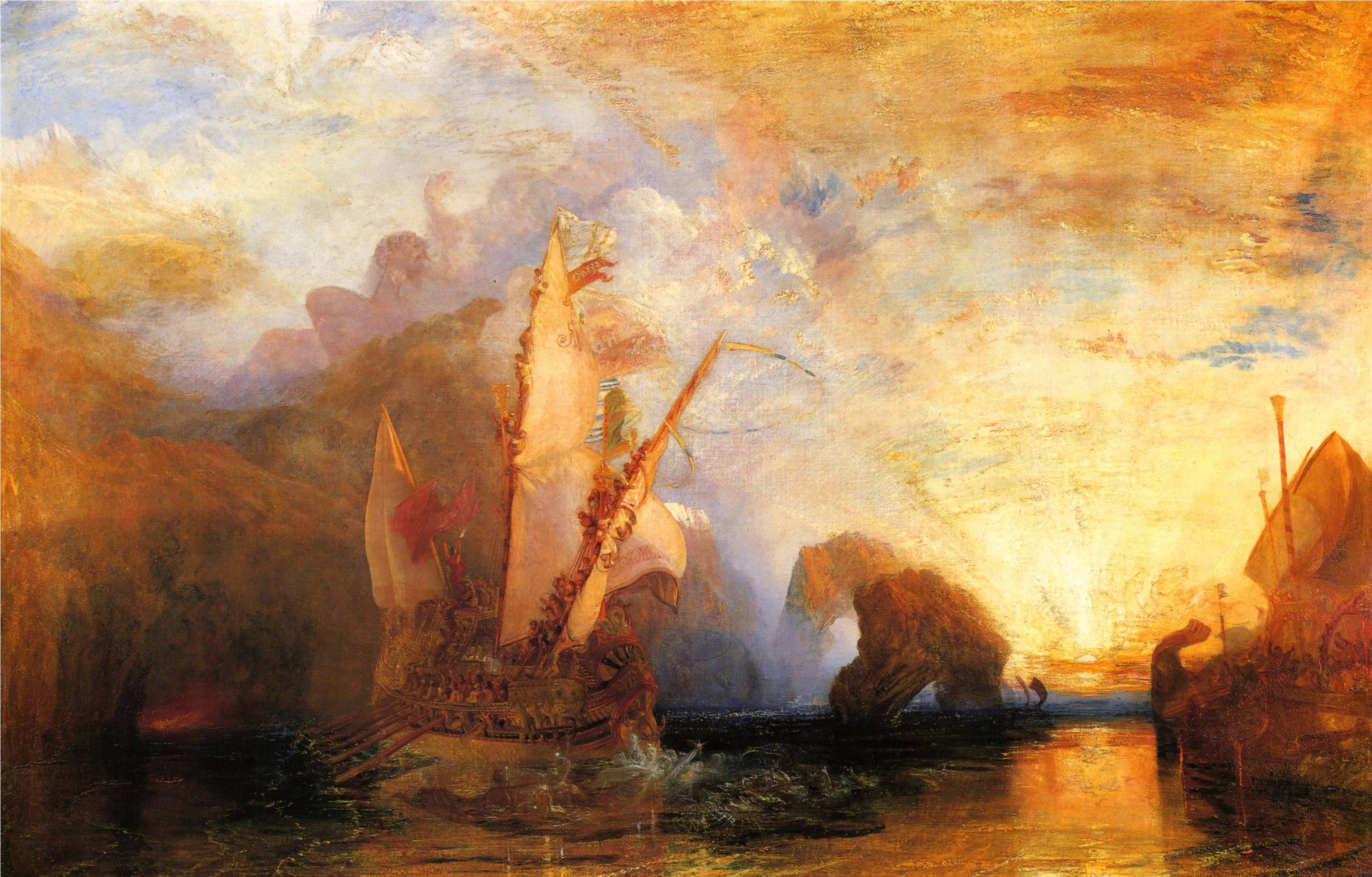

He himself compares the light and emotional effects he goes for here to the paintings of J. M. W. Turner, the 19th century English landscape painter.

In his article “The Paintings of Turner and the Dynamic Sublime,” George P. Landow points to how “in place of the static composition, rational and controlled, that implies a conception of the scene-as-object, Turner created a dynamic composition that involved the spectator in a subjective relation to the storm.”

Thus, one of the things that distinguishes Turner’s work as sublime is this sense of dynamic composition. In similar fashion, “The Approximate Present” uses a perpetually moving camera and constantly changing perspectives to maintain a dynamism between the viewer and the images. The film instructs us through this movement and these perspective jumps that our perspective is limited: if we are moving past the landscape, if we have many perspectives and are always moving to the next one, our time with these landscapes is fleeting.

Fleeting, yet recurring, as the film in coda like fashion repeats and we revisit the landscapes and the perspectives; the second time, however, they are altered by weather systems: repetition, but with a difference. We can return but our return is bittersweet, as the landscapes we return to are altered.

Landow’s analysis is part of a long tradition of artists and art critics seeking to account for this dynamism in landscape art: a tradition of the sublime. As Christine Riding and Nigel Llewellyn define it, in their article “British Art and the Sublime,”

‘the sublime’ is many things: a judgement, a feeling, a state of mind and a kind of response to art or nature. The origins of the word in English are curious. It derives from a conjunction of two Latin terms, the preposition sub, meaning below or up to and the noun limen, meaning limit, boundary or threshold. Limen is also the word for ‘lintel’, the heavy wooden or stone beam that holds the weight of a wall up above a doorway or a window. This sense of striving or pushing upwards against an overbearing force is an important connotation for the word sublime . . . By the seventeenth century, the word in English was in use both as an adjective and as a noun (the sublime) with many shades of meaning but invariably referring to things that are raised aloft, set high up and exalted, whether they be buildings, ideas, people, language, style or other aspects of or responses to art and nature.

Up to the limit, or, in other words, at the border, at the threshold of experience. Yet there is also this sense of a force they describe, here a beauty that exceeds words or even realist photography, sending hipsters everywhere scrambling to add instagram filters to approximate aesthetically what photorealism fumbles and drops at its feet. To be human is to take luckluster photographs of wondrous sunsets and glorious fireworks, these photographic failures each reminders that we can’t take it with us — the moment — that perhaps the most beautiful and experiential moments cannot be carried into the future with us, that, truly, you had to be there.

The sublime is vista, is landscape, but rendered in a way that is meant to challenge or engage the self and its aching, pleasurable sense of its own limits, but the sublime representation must also maintain the tension of that limit. To understand this, we need only look at a grotesque and excessive example of the sublime limit transgressed: the viral and eternally mocked and quoted “double rainbow.” You could argue that part of its viral force was due to its relatability, how words fail us when we are faced with the sublime. That the man gushes over the double rainbow does not maintain the tense limit of appreciation throws the sublime moment into the comic grotesque. The obviously high man on the brink of a possible triple rainbow makes a fool of him and what could have been a sublime moment.

This sublime tension, not to be exceeded, is wrought from two forces: a sense of melancholy failure, and the opposing and enduring hope of holding onto beauty and the experience of beauty. So it falls to artists to imagine how this might be possible. As Riding and Llewellyn point out, “It was at this point in the history of the word sublime [during the Enlightenment] that visual artists became deeply intrigued by the challenge of representing it, asking how can an artist paint the sensation that we experience when words fail or when we find ourselves beyond the limits of reason.”

In “The Approximate Present,” the absence of words means that the film can avoid the traps of pathetic fallacy, or worse, the trap of double rainbow blather, as it resists locating the vistas in one troubled or amorous psychology. No one tells us why we are looking at these landscapes, why we are traveling by plane, train, and car, or who we are in all this. There is no character referent, no avatar in the film standing in, interpreting or defining meaning for us. In addition, the repetition of the landscape with and without the weather locates contrasting emotional states, of wonder and more melancholy awe. These are inescapably our landscapes and there can be no singular awe.

Baraccani’s film, unlike the sublime Turner paintings he says inspired his lighting techniques, leaves human images out of the landscapes. The airplane appears as a condensation trail or the edge of a window that frames the view of the clouds, similarly the train appears as a line in the distance, and the shots from the train and the car are also framed by window edges, traces of the real world that barely edge the impressionistic landscape. Cars, buildings, and other human effects when they do appear are more impressionistic in “The Approximate Present,” where in Turner’s paintings the emotional landscapes are almost grounded by more realistic images like the ship in the painting above.

As a result, “The Approximate Present” is a consistently impressionistic and emotional landscape, and the absence of realist markers means we can’t look back at ourselves, can’t locate ourselves in any way that is not emotional. We are at sea, at sky, at landscape, inescapably.

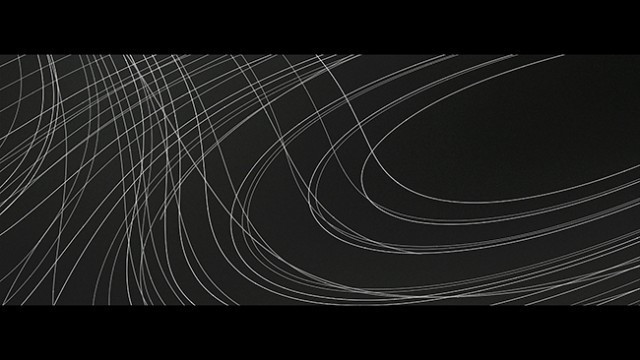

The only break away from this impressionism are the animations of chaos’s patterns. These patterns play out an oddly narrative frame for the weather: The lines drawing themselves, weaving around previous lines, even doubling back, define trajectories and demonstrate the past, where previous lines of weather have gone. As lines of chaos go, these seem oddly soothing and consolatory, signifying a logic or magnificent design, some sort of meaning behind the chaos. This, too, layers the weather and the landscape with significance, makes us see chaos as part of a larger pattern. For this reason, perhaps we are reassured, we are not wrong to feel these landscapes. They are significant, though we don’t know how.

Baraccani’s retro-animated shapes, constant camera movements, perspective shifts, and images of chaos cartography, combine to create a sublime landscape that avoids the had-to-be-there trap of landscape photography, creating animation that shares more with painting than film. “Approximate Present” creates a weather and chaos simulator that ultimately engages us in a game with our own emotions via vistas of our own experience of beauty in a virtual and always almost present.

—R. W. Gray