.

AT 9:00 AM ON A SUNNY MORNING, while your teenage son sleeps, make plans with your husband to visit the city of Briançon and the stronghold of Mont-Dauphin. Just over the Italian border in France, these are World UNESCO sites where the military engineer, Sébastien Le Prestre Vauban (1633-1707), designed forts and walls for the Sun King, Louis XIV.

Wake your son. Don’t tell him about the history trip ahead. You know he’s always hated history—facts have always proved slippery, elusive, dull. Instead, tell him you want to take him to France for a crêpe. When he hops out of bed without a complaint, hand him an espresso. While he’s in the shower, charge your camera batteries. Pack chocolate.

Smile when your husband says, surprised, “That was easy.”

At 10:30 am, let your son sit in the front seat next to you while you drive west. Hand him your camera. Direct him to take pictures of the road slicing through granite and slate. Remind him of Hannibal the Carthaginian and his elephants, of the Romans who fought the Gauls, of the Duke of Savoy who fought the Sun King. Tell him that armies have always climbed through the Alps first one way, then the other, shifting boundaries first one way, then the other.

Inhale when he nods.

Pull into a scenic lookout when he says “Stop.” Climb out and gaze at the rock scantily clad with snow while he takes pictures.

Agree when he says, “This road is tough, but without the asphalt and tunnels it was tougher.”

Where Italian and then French flags blow, at the top of the pass at the Col du Montgenèvre, say to your husband and son, “Bienvenus en France, mes chers.” Then, since you’ve forgotten your son’s ID, panic when you see gendarmes at the booth ahead scrutinizing arriving traffic. Look at the police straight on though, and smile when they wave you through.

Agree when your husband says, “Borders are porous these days.”

At 11:30, stop at the old walled city of Briançon that Vauban fortified after the Duke of Savoy pillaged the surrounding countryside in 1692. Park your car. Wind down steep streets to the main square. Buy a guidebook in a bookstore. Find a café. Order crêpes and pommes frites. Point to the fort on the crest looming above. Say, “Those rocks are a reminder of the past.”

Agree when your son says, between mouthfuls of buttery food, “These mountains are tough, but the men were tougher.”

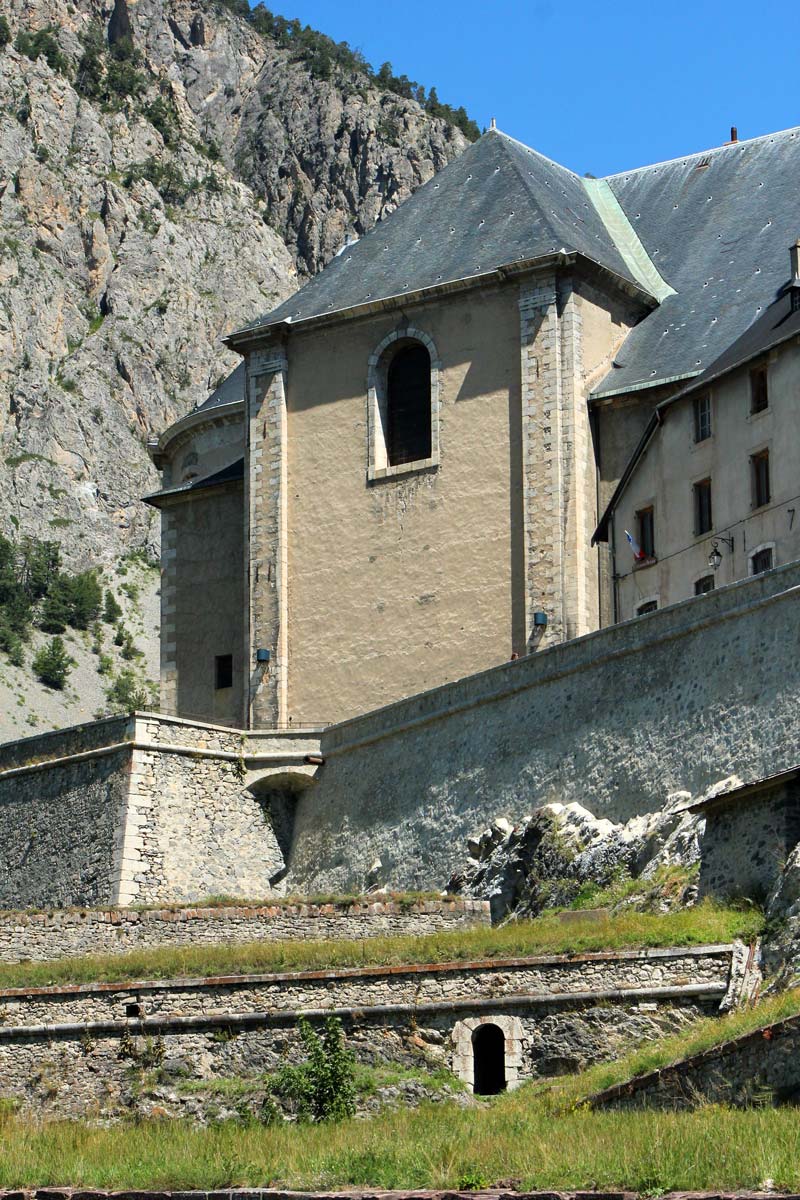

At 2:30 suggest getting ice cream down the road. Drive south for thirty minutes, alongside the Écrins National Park. Admire the winsome villages with spiky churches and red geraniums. At picturesque Eygliers turn left. Note that your son’s breath catches at the sight of Mont-Dauphin, Vauban’s citadel that crowns the Millaures plateau which means ‘at the cross of the winds’ in Occitan.

Ask what he’s thinking.

Nod when he says, “Those towers above are a cliff full of mystery.”

Together climb over grass-clad ramparts. Cross the bridge that fords the empty moat. Explain how Vauban began building this citadel in 1693 but that it came to a halt with the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 when the border was pushed elsewhere. Listen when your son reads aloud from the guidebook: “No actual battle ever took place here.” Shake your head when he adds, “too bad these walls went to waste.”

Buy ice cream. Lick the drips.

Circle clockwise. Photograph the church that was never completed. Photograph the remaining wing of the Arsenal where guns and ammunition were kept. Listen when your son reports, “the flanking wing was destroyed in World War II when Italians flew over and bombed it.” Agree when he adds, “So this place saw some action after all but it was only one brief blaze.”

Visit the cemetery. Look at the rusting crosses and dates. See how they’re relatively recent.

Photograph the main street where officers once lived. Together imagine how they waited for war that never materialized. Tighten your scarf around your neck again and again when the wind—the incessant wind—blows through. Notice how some places are boarded up and others are for sale.

Nod when your son observes, “This has always been a ghost town even when the soldiers were here.”

At 7:00 pm, climb in the car, head back down the hill, turn right onto the highway. Drive north along the Écrins National Park toward Briançon and the Alps. Honk at a camper hogging the road. Swerve left when a stream of bicyclists in black nylon and silver helmets encroach on your lane.

Agree when your son, who is now in the back seat, says, “Look, these are today’s road warriors.”

Ask your son his impressions of his day in France. When he says he liked the crêpe and the ice cream, sigh, but say “Good, I’m glad.” When he says, “I know it was a ruse to get me to come,” deny it. But smile broadly when he says, “The best part was walking where the armies had been. We should do this more often. Can I see the guidebook again?”

Don’t remind him you’ve always done it. Don’t list the museums and sites you’ve gone to together.

Shake your head when your husband says, “That was easy.”

Then hand over the book, pull out the chocolate you packed, and share it.

—Natalia Sarkissian

.

Natalia Sarkissian has an MFA in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts and has been an editor and contributor at Numéro Cinq since 2010. Natalia divides her time between Italy and the United States.

.

.

A bit of history, travelogue, and psychology all rolled into this piece of light-touch writing. The second person pov brings the reader right in.

Natalia’s writing seems so effortless when the reality is that writing this easy is the mark of many, many masterful decisions in its creation.

Bravo! She can take me on anothr road trip any time.

Thanks so much James! 🙂