.

THE OPENING SEQUENCE of Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty (La grande bellezza) begins with the mouth of a canon firing and ends a few minutes later with a tourist collapsing dead from the beauty of Rome. An operatic opening, the shots in this sequence expose a sordid relationship between beauty and death and anticipate one man’s journey through memory, loss and longing as he seeks something of more substance than la dolce vita.

This first sequence is distinct from the plot of the film, but operates as a thematic prologue. Everything of the film that follows could be said to be contained in these few minutes: the locals stand among the statues – a woman with a cigarette dangling from her mouth as she reads the paper and a man in his undershirt washing himself in the fountain – the garish tourists gawk, the steady cam passes by floating out over the cerulean fountain waters operating as the visual embodiment of the glorious operatic voices that also pass over all these images and the vista of Rome. Sorrentino, in his New York Times commentary notes that “Rome is a city where the sacred and the profane work together . . . they are tied to each other.” The divine and the destructive, the operatic and the mundane, the still as marble figures and fluid motion of the camera, all create an absurd and sublime mélange. Beauteous, yes, but unsettling too.

These tensions in the opening have something of Freud’s ‘Uncanny’ in them, appearing familiar and yet oddly unfamiliar. This uncanny offers a taste of the dream-like logic of the overall film to follow, a story world of outlandish parties with lascivious suitors, child artists, massive dance numbers and assorted revelry, then side journeys to strip clubs, secret enclaves of the city only accessible by a key master where they find night gardens and even a giraffe. All of this passes by, the visions of a somnambulant searcher, playing homage to other despairing artist journeys like Fellini’s 8 ½ and La Dolce Vita.

The central protagonist, Jep, is our guide and searcher here and the opening sequence, from canon fire to tourist’s death by beauty, tells us everything we need to know about his struggle, his searching. Ostensibly the canon fire, as Sorrentino in his commentary for the New York Times points out, indicates that it is noon and the listless and lazy characters in the film to follow are only just waking up from the reveries of the night before “they are lazy and always tired so they probably started their day at noon.” However, Sorrentino has the camera begin in the mouth of the canon and pull away so that the canon points directly at the film spectator. A moment of threat so great it is absurd.

The canon fires right at the camera and, whether it’s live ammunition or not, that shot is semantically connected to the tourist who collapses dead a few minutes later. The canon might go off every day at noon and might also be part of a historical display about Rome, but here it symbolically connects to the death of the tourist that prologues the film and runs basso continuo under the narrative that follows.

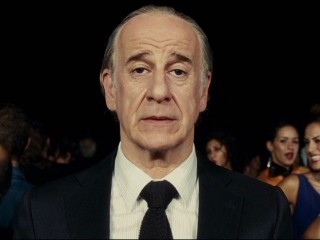

Yet, it isn’t the only shot that addresses the camera directly: there’s the canon that fires at us, the lead singer in the choir, her rapturous voice, her face full of melancholy jouissance, and then, when we finally meet him in the middle of his birthday party, there’s the face of Jep.

These shots are connected through their direct relationship with the camera: violence and the rapturous sublime build to the tourist’s death and then these all culminate in Jep’s ponderous and melancholy gaze as he stares down us and perhaps his own mortality.

Jep’s melancholy reflection directly pertains to the tourist he never meets. Sorrentino notes in his commentary for the NY Times that the tourist’s death is a “standard case of Stendhal Syndrome.” Though associated more with Florence, the syndrome is also connected to various psychosomatic afflictions involving travelers and other great cities like Paris, Jerusalem. In Paris, those afflicted are most often Japanese tourists who have so romanticized the city that when they arrive reality shocks them to the extent that the Japanese consulate has set up a crisis line for those afflicted. In the case of Florence, scientists recently monitored visitors to the Palazzo Medici Ricardi.

Graziella Magherini, an Italian psychiatrist who analyzed and specialized in this phenomena, named the syndrome after French author Stendhal who in one of his travelogues described “a sort of ecstasy from the idea of being in Florence.” Maria Barnes, a journalist who interviewed Magherini on the subject, felt herself compelled to explore the subject when she saw an American man faint beneath the Giotto ceiling paintings. In a confession that might as well be written by Jep she notes “For me, it is an exciting idea that art has the power to cause people to be seriously disoriented for significant lengths of time, perhaps because that reality seems so far removed from me. I can’t remember ever becoming directly emotional or having had a physical reaction to looking at art.”

For “The Great Beauty,” then, the psychological experience of travel, as troubling as it can be for many, perhaps allows us to reflect on the more static or stationary aspects of life, on the places where we don’t make room to be so moved by beauty. Sorrentino in his commentary notes that he chooses this location, the Janiculum, for the tourist perspective it offers: Rome seen from an outside perspective. Sorrentino also chose to preface the film with an epigraph from Paul Celine’s Journey to the End of the Night: “To travel is very useful. It makes the imagination work, the rest is just delusion and pain. Our journey is entirely imaginary, which is its strength.” The epigraph might seem misplaced as the film that follows tells the story of a man who seems, save a memory from a time by the sea, to have never left Rome. Yet the episodic, wandering structure of the film resembles a travel narrative and ultimately underscores that Jep’s struggle is not with an itinerary but with how to most deeply and meaningfully experience the time he has left, that inner travel.

Beyond its tourist perspective, though, the Janiculum has another significance. It is also a temple to Janus, the figure usually noted for being two faced in the sense that he sees to the future and the past. He is the god of beginnings and transitions, and a tourist’s death in a temple to memory and crossroads is a potent beginning for Jep’s story.

But it’s not enough that the tourist dies from beauty, swoons into oblivion. What follows immediately is a scream, one that could be added to the three direct camera shots I already noted: canon, song, scream, Jep.

Syntactically this would imply a shocked scream in response to the death of the tourist, but as the wail of the scream subsides and the camera backs away from the screamer’s mouth, it becomes apparent that she is screaming from so much party joy. What does this say about the man’s death by beauty? It is not grieved; it is not tragic; it is forgotten in the next frame in a sea of revelers. This isn’t just any roman party though, it’s Jep Gambardella’s 65th birthday party. A profound and powerful relationship to beauty is then juxtaposed with an irreverent and superficial dolce vita.

This collision of the tourist’s death and the party set up what is perhaps Jep’s central question and crisis: what is the difference between experiencing and living and what does beauty have to do with either? As Jason Marshall points out in his article “When Beauty is Not Enough,” the locals who wander among the statues at the beginning of the film provide a chorus of those who are insensitive to this question: “They are surreal figures, the kind that haunt most cities: idle and indifferent to the beauty and excitement around them, to the history they wash themselves in.” They are callous in comparison to the operatic experience of the singers above and the doomed-by-beauty tourist.

Other deaths string along from the first tourist death, accompanying Jep’s searching travels: the offstage death of Jep’s love from his youth; the dancer who dies, almost as an afterthought; the suicide of the tormented son of one of his friends; and, perhaps most looming and oppressive, not the death but the presence of the 104 year old nun Sister Maria, her faith and her reverence. Each in their own way interrupt and shape Jep’s wandering, question his questions before they die or leave him. And each are travelers with him, seeking meaning in the face of beauty and death.

We are left with the impression that little from the moment of that failed kiss in his youth, to the acclaim of his only book, to this journey of reflection for Jep has mattered, but as he travels through the city we also get the sense that the fellow travelers have given him fresh eyes to see the great beauties around him, to risk the pain of living and inevitable death. The tourist, as he falls to the ground dead in the opening sequence, is the apotheosis of feeling that has escaped Jep, and towards which he journeys. “Roma O Morte” is inscribed on the statue in those first shots, Giuseppe Garibaldo’s rallying cry to draw volunteers to his military and nationalistic cause, but at a glance here it suggests these are two options: Rome with its sort of immortal and limbo-like dolce vita, or a reverence for beauty that leads to death. Jep, by the end of the film, perhaps escapes this dogmatic binary, or at least as a traveler has an experience of beauty that will shape the words to come.

— R. W. Gray

.

.

Just loved this. Oh my goodness, while much rugged to die from sensory stimulation (more below) I experienced something similar when visiting Venice for the first time. I had spent six months reading everything I possibly could about the city, and as our train rolled along the outskirts and prepared to enter the terminal station, my stomach clenched with excitement. As opposed to disappointment however, Venice exceeded anything I could have imagined, but the damp and my general state of nervous overload resulted in a rotten head cold and sore throat!

My lust for Venice resulted in a.) notes for a never-finished manuscript; and b.) resurrection of these notes for two other novel drafts, one ancient/one modern, that remain active. Anything for an excuse to “live” in Venice in my mind.

Oh, those poor Japanese tourists in Paris. On a much more rural scale, I encountered a group of Japanese Patsy Cline Superfans in the 1990’s in Washington DC. They were heartbroken when they saw the disrepair of Miss. Cline’s birthplace out in rural Winchester, Virginia, and realized the blue-haired matrons of Winchester still considered her a “hootchie-tramp.” I think they all made it back to Japan safely however.

Finally, on the topic of my peasant constitution, I visited Japan in November 2003. I stood low to the ground, a big-busted, stout-bellied matron with a round pink face, a human perfectly engineered to dig potatoes. At a harvest festival in Tokyo, a group of elderly Japanese workmen beat on sets of sticks and made the rounds of the stalls (prominently featuring a Harvest Goddess image).They pointed to me, to the round-faced, pink-cheeked, tubby Harvest Goddess (my twin) and invited me along as they chanted and beat their sticks. So, even though I was not svelte, and felt like a fireplug during the entire visit, the workmen likely appreciated my ability to pick rice, bear many sons, and survive hungry winters! Japan is a complex place.

Best to you; once again am boggled by your analytical flair.

Maureen Murphy (Moe Murph)

So sorry, line one should read: “while much too rugged.”