Pechal moya svetla

My sadness is luminous, is bright.

Pushkin

A true Russian pastime. How best to conduct oneself in the hours and then minutes leading up to one’s destiny? The sleepless nights, and pallid skin were necessary; one could carouse and fornicate showing no signs of fear; at the barrier itself one might eat ripe cherries from one’s hat and spit the stones at one’s adversary, or lying in the snow at Chornaya Rechka, already struck in the bowels with the lead which would kill you, you could prop yourself up on your elbow and return fire at your fellow duellist, shouting “hurrah” when your bullet seemed to find its mark. A cuckold, a fool, a poet, a man, a failure. But there is beauty in the arrangement of words, these words I shore against my ruin, a beauty which struggles against the tragedy of existence. Let me tell you how it began . . . . The Nigger of Peter the Great . . . . I inherited the full lips and hot blood of my ancestors. I must tell you frankly: “proper women and lofty sentiments are what I fear most in the world. Long live tarts! . . . I may be elegant and proper in what I write, but my heart is completely base and vulgar and my inclinations all third-estate.”

To my life then. . . . I had married Natalia Alexandrovna, and her beauty was my downfall. In my lifetime I had met many beautiful women, some who gave off a certain maddening perfume, who quivered in a certain way at the final moment, and others who thrashed and moaned until I was glad to finish and take my leave, those who feigned shame and forced tears to their shadowed eyes and covered themselves with silken underthings, and still others who were grateful as if some ethereal gift had been given; of them all, in bed at least, I preferred the women of certain professional houses, those who knew the secrets of the body, took matters in hand, and explored the terrain with professional interest. But never had I encountered a woman such as Natalie: elusive, cold, like a distant star surrounded by its own magnetic field. Beauty beyond explanation or criticism. At the court balls she loved so much, charming women would turn pale with envy, and guardsmen lapse into painful silence. I made love to her as a mountaineer climbs the coldest, most remote precipice. The fevered kisses of my thick lips caused only sighs and accusations, a withholding and turning away, a body which in its whiteness seemed more a statue than a living vessel, the stillness of which nearly drove me mad with desire, her lips which reminded me of those whom I had caressed this way before, of those who had moaned and lost themselves to my whispered entreaties, the probing insistence of my hands. I hold “your long, elastic form” dear Natalie, in memory now, “but all you give me, my sweet friend, / Is a mistrustful smile” . . . You must know that for me no more “the madness of the flesh, the wild embrace, / the sobs and screams of a young bacchante / Who, writhing like a serpent in my arms/ . . . Hastens the moment of decisive spasm.” Natalie, my wife, I eternally seek your rejection beyond all raptures, your unwilling moan, drawn from your throat at the moment I seek purchase, and fall, upon your remote, immobile slopes.

****

At the Winter Palace during the frigid nights a woman, no longer my wife, dances effortlessly with the guards, the blood racing to her flawless shoulders, her happiness with other men a palpable fact and a right. In the shadows, alone, a man who comes to other’s shoulders, whose legs are bent, whose heart is broken, whose face is dark and lips are thick. A monkey, a tiger. A poet standing alone by the columns. And this was me—Gentleman of the Chamber, in a plumed tri-corn hat and patent leather boots, occupation for a fumbling adolescent, not a poet . . . But poetry is not life no matter how much one might wish it so; it simply goes grinding on, the sheets always soiled by those who come before . . . by those who must come after.

And then, from across the room, comes the one whom I have been waiting for; the one whom I know I shall have one day to kill; he arrives with the curling mustaches of an adolescent, blondly gleaming in the hall of mirrors, the one who dances so well; the one who will not leave my wife alone. I stand alone in the shadows of the colonnades, watching them make love to one another, and in my impotence, my legs grow weak, poetry becomes a lie, and I am a slave standing on twisted legs. My wife dances in a world I can never enter. The story is boring except for those caught within its snares. In the forest there is a melancholy song, tolling out the hours of our days: Cuckoo, cuckoo.{{1}}[[1]]The society of cuckoos, to which many belong but none aspire. The letter that set everything else in train, and finally sealed my doom arrived by anonymous hand in early November: “The Most Serene Order of Cuckolds, meeting in plenary session”, it began and I already smelled cordite in the air, “have unanimously elected Mr. Alexander Pushkin Coadjutant to the Grand Master of the Order of Cuckolds and historiographer of the Order . . .” [[1]] There are “two types of cuckolds in this world: some are so in fact, and they have no uncertainties about their position; others are made so by public opinion, and their position is far more difficult; I am one of those”. . . .

And so D’Anthes and I must duel—for that is the given name of a bastard. Everyone now will have heard of it; the details remain dull, overly romantic, as so many ends are. So then, if we must, I am yours, at Black River, on the road to Pargolovo, near Odoevsky’s Estate . . . . with the light failing.

The final day: First things first, clean linen and bathed—preparations against the worst. Then to business: response to a lady writer. “I am very sorry that I shall not be able to accept your invitation for today.”{{2}}[[2]]My last letter to Alexandra Osipovna Ishimov—children’s author and translator (27 January 1837).[[2]] Silly, but even poets are not given to choose their final words.

In search of a second on the streets of the capital: a dangerous business, finally I pluck Danzas from just over the Tsepnoy Bridge near Millionaire’s Row and, old friend that he is, he may not deny me; the pistols, embraced in oiled wood and soft velvet, lovely; at Wolff’s pastry shop on the Nevsky, the sound of tinkling glasses, lemonade, bitter in my throat, laughter, cold breath, coffee and sugared pastries; back in the carriage on the Nevsky with the winter light already raking low on the horizon; we might have seen Natalie and the children pass if we had looked, or if she had thought to wear her spectacles, the vanity of beauty. Nothing else for it, with carriages already coming back from the islands we cross the river at Trinity Gate, glide past the Fortress onto Kamenovstrovsky Prospect, then along the Rechka toward the “slides” and “the commander’s house.”

Impending death will concentrate the mind wonderfully, cause the spittle to cake in one’s throat. In a lonely field I sat while they stamped down the thigh deep snow. D’Anthes, already with pistol in hand on the far side of the barrier. And I turned away.

“Is the site well chosen?” someone asks.

“I don’t give a damn, just hurry up and finish.” My voice, it seems, far away.

“Ca m’est fait egal, seulement tachez faire toute cela plus vite.”

“Eh-bien! Est-ce fini?”

In the moments before our meeting, I stand facing the trees and notice small things: an animal track in the crusted snow, my cracked and shaking hands, already cold, a Hebrew signet ring given me by Countess Vorontsova slipping off my shrunken fingers, hands that in a moment will hold the pistol and decide our fates; Eliza, the one who had made love to me in the southern surf like a slippery seal, a great lady who went down in the sand, and her husband a knowing cuckold, much as I was at this moment, and thus this ridiculous duel between overgrown boys, whose honor isn’t worth one line of real poetry, of life. Just as I stood I wondered about the meaning of my wretched existence, the women who were like poetry to me and as dangerous, the undying love which was already dead as it was uttered, the debts, the cynical crowds around the throne, my attempts to be a writer, a poet, and what else? . . . yes, Natalie, her opaque mind and her irresistible beauty which led me to this place. She was not to blame, others never are. It is always our choice, our heart. A poet, a failure, a . . . . I had tried “all genres . . . and at the very end even the genre of life seemed not enough.” With guns at the barrier then we would put an end to words, compel silence to speak. Thank god for that.

And so, I stand to face my foe—odd word, foe, as if blood in the snow, a ball pushing through one’s intestines, shattering one’s hip, were in any way romantic.

Everything happens very quickly then. We move toward the barrier, but before reaching it D’Anthes raises his arms and fires first. Why didn’t I take my chance? I don’t know. Perhaps I thought he would miss. He didn’t. Who knows why. The sky is cobalt above my head as I fall in the snow. At first nothing, and then pain as big as the world. Danzas comes to me with an odd look on his face; the snow melting on my face, and I shivering. Somehow, I am able to raise myself on my elbow and raise the pistol.

“Attendez! Je me sens assez de force pour tirer mon coup.”

“I may take my shot.” I fire, and the blonde one staggers and falls.

I hear someone yell: “Yes, I have him.” “Hurrah!” My voice muffled in the endless whiteness. “The bullet? Where?”

“Have I killed him?”

“No, but he is wounded in the arm and chest. “

“It’s strange, I had thought it would give me pleasure to kill him but now I feel it would not. And yet it’s all the same; if we recover it will all start again.”

A cuckold will always be a cuckold, will never triumph in that ageless duel. D’Anthes stands again, a pillar of ignorance and desire untouched by any poet’s phrase. The ball has only penetrated the soft part of his arm, and raked across his ribs. I see him then with Natalie, locked in that mindless embrace that makes fools of us all, and the pain washes over me in waves, in ways I cannot explain, and I do not know how they get me to the road, or home . . . . Back past the Fortress in the darkness, the lights of the city, blood weeping from my body in cold tears, my life, through the muffled winter streets of our capital, and I know that “on such a night as this to toss and turn in one’s bed is better far than to stand unmoving, immortal upon a pedestal.”{{3}}[[3]]A poet I could never have known—Joseph Brodsky—who was also driven from his homeland, wrote these lines of elegy 150 years after my death. I thank him.[[3]] It seems, though, we have little choice where we will come to rest, and the story will have already begun; the living , not long for this world themselves, will already have begun to package up my death like a poorly written novel. Our frolic in the snow with the light failing. In two years it, and I, will be completely forgotten. . . . Mistaken, as it seems.

They bring me home to the Moika already dying. Through the servant’s door and up to the mezannine, the crowds already gathering, whispers, tears. A woman’s voice: “No, he shall not die”. . . . And my own: “No, I do not want to die, my friends! I want to live, in order to think and to suffer”. (Elegy)

Oh, Natalie, I loved your ivory beauty too well: a continent I would never conquer, a gift I could not receive, and did not deserve. Poems written for that which I could not touch: “I loved you once, nor can this heart be quiet . . . What jealous pangs, what shy despairs I knew! A love as deep as this, as true as tender, God grant another may yet offer you.” These words at least were beyond reproach.

The bullet had passed merrily through my abdomen, searing the intestines, finding rest in my fractured hip bone. Two days in dying, until only the opium kept me sane. And all I wanted were blackberries in syrup given by Natalie’s hand—no my dear you are not to blame, not to blame. You mustn’t cry. Only listen . . . “Try to be forgotten. Go live in the country. Stay in mourning for two years, then remarry, but choose somebody decent.” Everything has turned out for the best.{{4}}[[4]]Natalie, dear, you did stay in the country for a year, and when you came back to our fair capital you stayed away from the court altogether, until one day you met the Tsar—almost by chance?—in the English shop at Christmas. He kissed your hand, bowed to your still unfaded charms, and began to think how he might do something for you. And so the game began again. Introductions were made to Lanskoy, thirteen years your senior (you always liked older men), mediocre talent at best with no particular prospects; suddenly he found himself appointed Major-General to the Horse Guards, fortunate man, and marriage was not only possible but convenient. You scarcely cared about the flesh anyway, and he said he loved you. There were children, and thank god no poetry. And you died in the autumn of 1863 choking with consumption—how is it possible?—and your husband followed you a full 15 years later, and you are both buried under the same stone in the Alexander Nevsky Monastery. I am alone now, Natalie. I miss you.

As for the blonde one: he married Natalie’s sister—Ekaterina—and repaired in disgrace to Berlin, then Soultz in Alsace, Haut-Rhin; did he make love to Natalie’s marble body while he held her sister in his arms? They produced children together and poor Ekaterina died just five years after this marriage of the heart (hers) and convenience (his). D’Anthes lived a long life, a political life—so unlike a Russian poet—with residences and business in Haut-Rhine and in Paris, and died in his bed in 1895, the father of many children, a councilor, a chevalier, a senator, and is remembered chiefly as the one who killed Pushkin at Black River. [[4]]

Last words of a poet:

“Why this torture? Answer me: is it fatal?”

“Do not hold out any false hopes for my wife. She is no actress.”

“It seems life is coming to an end. . . . Please close the shutters.” A classical observation, perhaps, though rather obvious.

“It’s nothing, everything has turned out for the best.”

“If I must die then, Il faut que j’arrange ma maison. I must put my house in order.”

To Dahl: Come let’s fly together, up the bookshelves, but I am dizzy and cannot fly, and must fall. I cannot breathe, something is crushing me. Finis.

To a lady writer once more: “. . . I am very sorry that I will not be able to accept your invitation for today . . . or ever if it comes to that.”

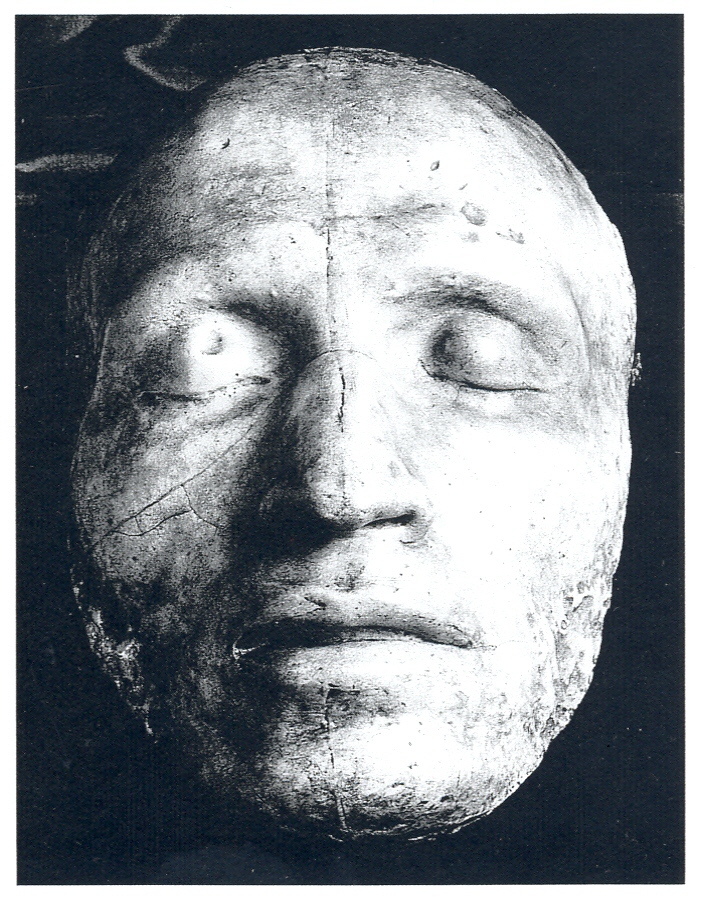

The autopsy: “Small intestine affected by gangrene. That is probably where the ball entered. In the abdominal cavity there was not less than one pound of black, coagulated blood. . . . The ball traversed the abdominal integument two inches above the right spina iliaca anterior superior, passed along the surface moving downward, and, upon encountering the resistance of the sacrum, fractured it and lodged nearby.” The faithful Dahl again.

All very neatly said, a poetry of a kind itself. And now the time approaches. Stray strands of poetry rise up to greet me. My friends, let us walk together a while. . . . “Along a noisy street I wander; and beneath the eternal vaulting someone’s hour is drawing near, for growing youth must have its own good place, the one to fade the other to bloom” . . . Welcome darkness now, “I only ask that at the entrance to my grave, young life may be at play, and that nature unconcerned with mortals may shed its beauty’s timeless ray”. Even dying becomes a little easier with this consolation.

And the Tsar said: Your family is mine. Do not worry about your wife and children. They will be my children and I will take them in my care . . .

I knew a sadness then which was luminous . . . and my being grew calm and still because this heart beats, is alive, and cannot but love. . . . At earliest morning, I dreamt my love had turned to me, her breath sweet with sleep . . . and I knew a happiness given only to the blessed. . . Then sweetly, softly, ever so softly, dawn crept out of the night in Pieter . . . and I walked into the light.

29 January 1837 2:45 in the afternoon

By anonymous sledge my body was borne to the north. They lay me in the cold ground of Svyatigorsk—the monastery of the holy mountain—next to my people, the descendents of Hannibal, the negro of Peter the Great.

* * * *

A Dream Early Evening 15 July 1841. Outside Pyatigorsk

By hot noon, in a vale of Daghestan,

Lifeless, a bullet in my breast, I lay;

Smoke rose in a deep wound, and my blood ran

Out of me, drop by drop, and ebbed away.

She dreamed she saw a vale of Daghestan . . . .

on the slope a well-known body lay;

Smoke rose from a black wound, and the blood ran

In cold streams out of it, and ebbed away.

(Mikhail Lermontov)

Does a fatal bullet wound really smoke in one’s breast? It was raining, as if the heavens were yielding, as I lay dying beneath Mashuk’s slopes. Muffled thunder and sodden earth. My body, my corpse, carried back to the town of five mountains, Pyatigorsk. God, what a country! Cherry trees and mountains—five peaked Beshtau, Mount Mashuk, the snowy summits of Mount Kazbek, the distant shadow of Elbruz. At earliest dawn the window open and the perfume of flowers draws me from the happiest of dreams; the branches of cherry trees in bloom reach in at my window, a lover’s caress, and the wind occasionally strews my desk with their white petals. A joyful feeling fills my veins to overbrimming. Is there any need here of passions, desires, regrets? (81-82).

Twenty-six years by the grace of God, in a dale of Daghestan. My life oddly reminiscent of a novel I had written not long earlier. Geroi Nashovo Vremeni—A Hero of Our Time which was, I said: “a portrait of all the vices of our generation in the fullness of their development. . . . However, do not think after this that the author ever had the proud dream of becoming a reformer of mankind’s vices. . . . He merely found it amusing to draw modern man such as he understood him, such as he met him— . . . Suffice it that the disease has been pointed out; goodness knows how to cure it.”

I believed only in poetry . . . that and the blood of the poet. Smert’ Poeta; “The Poet’s Death” they called it, and mentioned my name in the same breath as that of Russia’s fallen poet. Immensely flattering, and somehow completely irrelevant, a romantic lie that might help poets rest quiet in the ground if they were in the business of purveying meat pies at Kuznetsky Most, which they were not. I wrote:

And you, proud sons of famous fathers – you,

Known to the world for vileness unsurpassed,

………………………….. . .

You greedy crew that round the scepter crawl,

Butchers of freedom, genius, and renown! . . .

Law, truth, and honour—in your steps cast down!

………………………….. . .

In vain your viper’s tongues with poison dart,

And all your black blood will not wash away

The godly lifeblood of the poet’s heart!

These lines composed as Alexander Sergeevitch lay dying on the Moika; I had never met him, had only seen him pitched like black thunder from across glittering rooms, watched as they destroyed him, as they despised his poet’s blood. Somehow the words seemed far away from my life as soon as they were written, much better than my life, somehow already foreign to my deformed existence. And yet history it seems had a place for me. For my pains they exiled me to the Caucasus, my beloved, lonely Caucasus. I should have read my destiny in the stars, fatally embedded in the window glass of eternity, just as it was for my brother poet, words would be silenced by the gun, and the world would just go grinding on in its drunken, lascivious waltz.

God, what a country!! To never see it again.

To ride out on the virgin steppe, saber at my side, to climb up to the Mountain of the Cross and gather the stars in one’s hand at Dariel Pass. I sought this freedom, this life, and found only a prison. I felt my skin begin to constrict about my soul, and with “Mongo” Stolypin I sought escape. There was riding out on the line with cutlass and sash, exposed to the hidden rifles of Kabardins, Circassians, hill tribes who did not yet know the saving grace of Christ. Cordite, blood and excrement. Something like roulette, a Russian fatalist, with one fatal chamber loaded. Apparently it was not my time. No bullet reached me. Nor were cynicism and cruelty beneath me; women’s innocent tears moved me to yawning boredom; and I did not need their bodies; as for the silly fools who drank the sulphur waters, who limped and ambled and played at being plaster soldiers, well, the romantic melancholy was really not in their line. My hand twitched and reached for my pistols. Words would no longer serve.

I really could not take the Monkey seriously, the montagnard au grande poignard{{5}}[[5]]The mountaineer with the big dagger, if you must know. And the Monkey: otherwise known as Martynov, decommissioned officer, poseur, spa town ladies man.[[5]] I called him, and this allusion to his manhood caused the ladies to cover their faces with their fans. And then I had made love to his sister years ago; no, I really couldn’t take him seriously, though he was the very devil with the ladies in his Circassian costume. Certainly there would be no duel, and if there were, well, there would always be the fatalist’s coin toss, interesting at least until it fell to the ground. I thought of women I had known, who while embracing another, might begin to laugh at my memory so as not to make their new lovers jealous of a dead man; and I didn’t give a damn about any of them. Perhaps I should die on the morrow. “The loss to the world would not be large and, anyway, I myself was sufficiently bored.”

Martynov, the fool, insisted on satisfaction. (“How many times have I asked you to abandon your jokes, at least when the ladies are present?” he said.)

Yes, really a very large dagger, I thought to myself; this is nothing, tomorrow we’ll be drinking the waters together as friends again.

But, as always, my tongue was my worst enemy. I said: “Really, Monkey, are you going to get seriously angry and challenge me to a duel for this?”

The Circassian warrior of the drawing room drew himself to his full height: “Yes, I am calling you out.”

There was more to him than I had thought. So be it. The barrier was set at 30 paces, and we were to approach 10 paces closer. What silliness. I had no intention of firing on anyone on such a fine day—and I remembered Alexander Sergeevitch’s story in which the duelist refused to use his weapon but instead spat cherry pits across the barrier. But there were no purple cherries to be had on this fine day. I raised my pistol to the sky and for some reason could not stop myself from one final bitterness in this world: ya v etovo duraka strelyat ne budu, I shall not fire on that fool. A worm twisted in my body, searching through the left side of my strawberry shirt—strawberries for luck—passing though the willing flesh of heart and lungs, and out into empty space again. Then, darkness. And no more pain.

I lay in the rain, in my strawberry shirt, red-on-red in a dale of Daghestan; I dreamt of mountain precipices, of crimson peaks, of a solitary sail seeking distant lands—and my blood grew cold and ran away. A fool of time.

And the Tsar said: A dog’s death for a dog.

Two years later, my grandmother took me to the family tomb at Tarkhany, where you may visit me as you please.

—Myler Wilkinson

Selected Reading

Pushkin, Alexander. Pushkin Threefold: Narrative, Lyric, Polemic, and Ribald Verse. Trans. Walter Arnt. NY: Dutton, 1972.

______. The Captain’s Daughter and Other Stories (contains “The Shot”). Trans. Natalie Dudington & T. Keane. NY: Random House (Vintage Books), 1957

Binyon, T. J. Pushkin: A Biography. London: HarperCollins Publishers. London: 2002

Edmonds, Robin. Pushkin: The Man and His Age. London: MacMillan, 1994.

Troyat, Henri. Pushkin. Translated from the French by Nancy Amphoux. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1970.

Lermontov, Mikhail. A Hero of Our Time. Trans. Vladimir Nabokov in collaboration with Dmitri Nabokov. Garden City, New York: Doubleday Anchor, 1958.

______. Major Poetical Works. U of Minnesota Press, 1983.

Kelley, Laurence. Lermontov: Tragedy in the Caucasus. New York: George Braziller, 1978.

Vickery, Walter N. Mikhail Yurievitch Lermontov. His Life and Work. Munchen: Verlag Otto Sagner, 2001.

/

Myler Wilkinson—author of numerous articles and essays on Russian culture and literary history, and has spent extensive periods of time over the last 25 years in Russia. He has published three books—Hemingway and Turgenev: The Nature of Literary Influence, The Dark Mirror: American Literary Response to Russia, and Russian Journal: A Personal Journey—all of which explore imaginative and cultural crossings between Russia and North America. He is the anthologist and co-editor, with David Stouck, of two volumes of British Columbia writing—West by Northwest: BC Short Stories and Genius of Place: Writing about British Columbia. In addition to his non-fiction work, Wilkinson has also published award-winning short stories in journals such as Prism International (25th Anniversary Anthology) and Pierian Spring. Currently he is working on a story cycle which explores the lives of Russian writers. “The Duel” is one of those stories: it follows Alexander Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov on their ways to the duels that end their lives; this work is linked to the story “The Blood of Slaves,” which was winner of the Fiddlehead Fiction Prize for 2014, based on the life and death of Anton Chekhov.

/

/

/