Six Russian soldiers. Young, maybe nineteen. One of them is calling for his mum, all of them are begging for their lives. They are butchered one by one. The way one of them twitches when the blade cuts his neck, the sound of the blade sawing through bone and artery. Or Mihai Antonescu, facing the firing squad in 1946, turning around to get rid of his hat, to throw it behind the pole where he will be shot – a man about to die and yet worried about his hat. Hussein not finishing his rant. The anonymous guy in a hanging video, shitting himself. An American’s politician’s brain dripping through his nose. It’s always in the details, the details always catch you unaware. The punctum of these moving images, the things not necessarily anticipated by the camera. The ones that stay with you.

*

A

short sequence in Antonioni’s The Passenger stands out from the rest of the film. Shot on 16 mm, in saturated colours, the grainy footage depicts a public execution on a faraway African beach. We see the prisoner handled by guards, then tied to a pole by the sea, a priest having his final say, locals gathered to witness the spectacle, a coffin waiting. A firing squad is in charge of taking this man’s life and soon the first volley of shots hits his body. The camera zooms in, to an out of focus close up of his face. In comes a second burst of fire. Clearly in pain he raises his hands, slowly, perhaps trying to stop the bullets. His body shakes, departs. A jump cut takes us away from his death and into a convertible with Jack Nicholson and Maria Schneider, the main characters in the film.

Still from the execution scene in The Passenger..

Still from the execution scene in The Passenger..

The Passenger, from 1975, is a work of fiction. Yet this scene has all the hallmarks of the mondo film: brutality, a black body dying on camera, Africa. This genre – quite popular at the time thanks to films like Mondo Cane{{1}}[[1]]Jacopetti, Cavara & Prosperi, 1962[[1]] and Africa Addio{{2}}[[2]]Jacopetti & Cavara, 1966[[2]]– is renowned for its constant flirting with death (forged and real), sensationalism and erotic exoticism. The black body, semi-naked, in pain, dying, already dead, in all its alienness, perceived brutality and essentialist sensuality is one of its main attractions. Perhaps Antonioni was criticising the genre, yet in narrative terms this execution is introduced in The Passenger with the intention of providing a realistic seal and a geopolitical context to the main character’s misadventures during the tumultuous process of decolonisation in Africa. That said, what makes this sequence stand out from the rest of the film is that it is indeed documentary. This is no fiction, this is the real thing, the execution of a Nigerian petty thief fictionalised as the execution of a political leader{{3}}[[3]]Walsh, M.(1975) The Passenger: Antonioni’s Narrative Design, Jump Cut, 8, pp 7-10.[[3]] – not that it is possible for an execution to be apolitical. Antonioni puts reality in the service of fiction in order to deliver a realistic narrative. It is complex, and problematic.

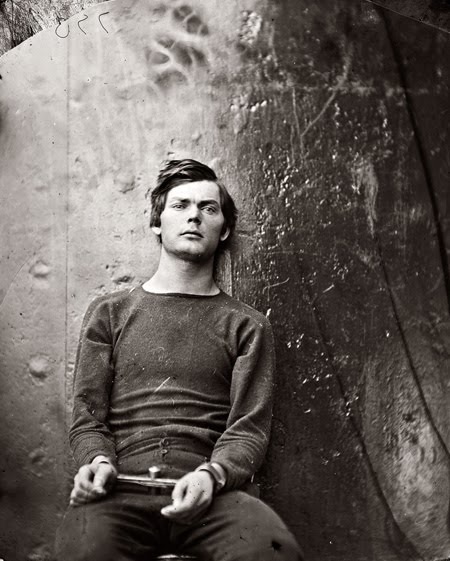

I have long been haunted by this scene, and not only by the ethical implications of turning death into entertainment. There’s a mechanics of dying on camera that keeps my mind busy. This man is alive, he is being killed, his death is being captured frame by frame. He is always still alive and always already dead. As every photograph, as every film, it reminds me an oft quoted moment in Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, when upon looking at the image of Lewis Payne – sentenced to death for his part in the conspiracy to kill Lincoln, Seward and Johnson – he claims: “He is dead and he is going to die”. In the case of film we could perhaps say “he is dead, he is going to die, he is constantly dying”. For as long as there remains a physical copy of the film, every time we press play we kill this unknown Nigerian man. Twenty-four frames per second we kill him. We stretch his unnatural death over time and repeat it at will. Yes, every image is sooner or later the image of death, but there are proximities and intersections – it isn’t the same to film a baby than a man being shot. An image of actual death has a power that no other image can claim for itself. Bare life (Agamben) doesn’t get any barer than this..

Lewis Powell, Lincoln assassination conspirator.

Lewis Powell, Lincoln assassination conspirator.

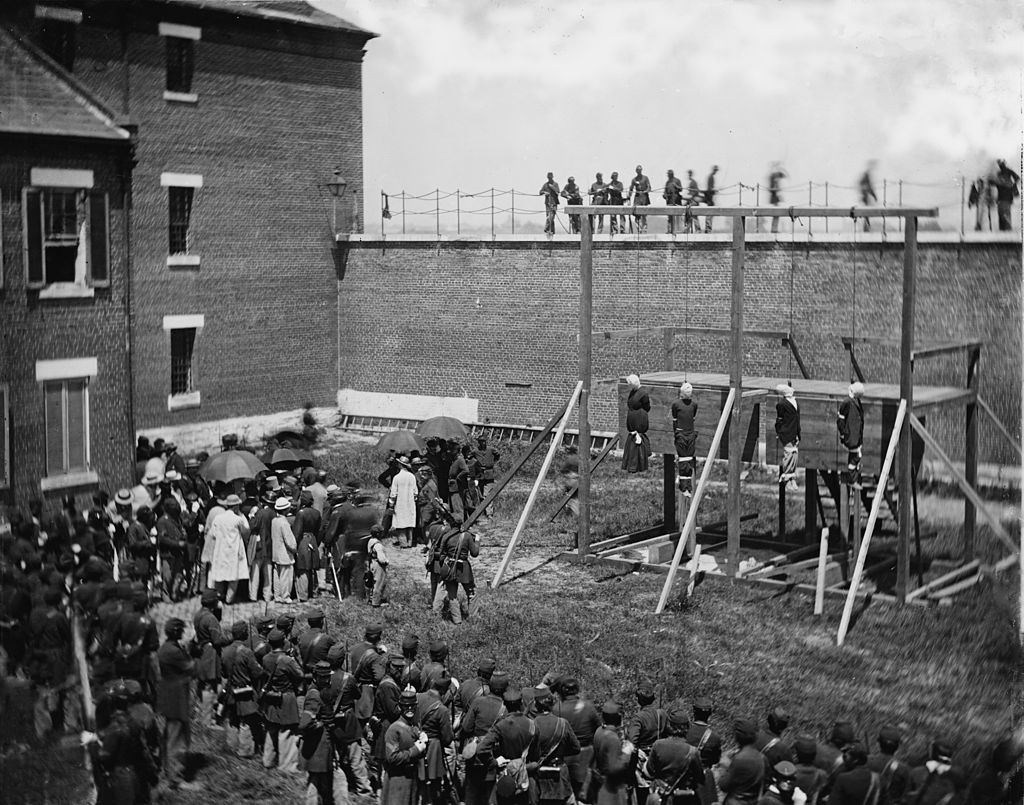

Execution of Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt on July 7, 1865. Via Wikipedia.

Execution of Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt on July 7, 1865. Via Wikipedia.

And how is a celluloid death different from a digital death? I think about film and those twenty-four frames per second. I think about a particular frame in which the victim is still alive. There is a frame afterwards in which the dying person is already dead. If we had the actual film roll in front of us we could easily mark these moments, we could easily perform a cinematic autopsy. Frame 374, the subject is still alive; frame 375 the subject is now officially deceased. Nothing of this sort can be carried out on video. Digital death is a more ambiguous transition, harder to locate. You can freeze the image, yes, but how do you know how many pixels of death and how many pixels of life there are? Digital death is confusing, immaterial therefore deadlier – and yet more common. I guess something of this happens with analogue death transported to digital as well. Adopted by a new medium it becomes ungraspable. One more thing to lament from the digitalisation of everyday life

*

You wouldn’t bump into death on the screen by chance, not too long ago. I had heard about the mondo films and there were rumours of snuff flicks doing the rounds, supposedly shot during the – dictatorial –70s in Latin America, but I had never seen any of these. I had also heard about Vic Morrow, who used to play Sergeant “Chip” Saunders in the series Combat!, about his death on camera together with two child actors, shooting a dangerous scene for a John Landis’ movie, the three of them torn to pieces by a helicopter blade. I used to watch Combat! with my grandpa in the mid 1980s – Morrow’s death was the stuff of legend. For years the thought of his head flying in the air tormented me, and the lack of closure – the lack of an image – was disturbing. All these moments of celluloid were mythical, for death on camera was invisible. I was born before the VHS, cable TV, and the internet; I was born even before colour TV in Argentina. Now you can find Morrow’s death on camera with a simple Google search..

The execution scene from The Passenger was my first. I might have been fourteen or fifteen when I saw the film. It was a rare, raw, and quite unique experience. Particularly because I saw it at an underground cineclub in my hometown Rosario – you couldn’t press pause back then. You never fully owned the image; you were always lagging one step behind, constantly losing your grip over what was playing out on the screen. Was it a real execution or just a very well performed fiction? It was impossible to tell. I trawled the local library trying to find information about this scene; I interrogated my cinephile friends. Yes, it is; no, it is not. The uncertainty remained for a while and then, yes, it was real, some scholar discussed this scene in an obscure film journal. Supposedly Antonioni had decided to use it after receiving some film rolls through the post, sent by who knows who. Patrice Lumumba’s execution was mentioned in the text – apparently the “educated” viewer would connect this murder with that other one. I often wonder if anyone ever made that connection.

It would be years until I saw another death on camera. This time it was an American politician shooting himself in the mouth. It had happened in the 1980s, but in Argentina we only learned about it in the 1990s – death on camera, when visible, used to be a delayed spectacle. This one didn’t take me by surprise, for it came with all the warnings and at 9pm on a very popular caught on camera show. Death on camera was making its first steps into primetime television and then along came the internet. Is there a medium more inhabited by death than the world wide web? You don’t need to stray too far from your familiar territory to dive headfirst into death. The internet is the deathtube. The images are up online while the body is still warm – digital death is immediate. Digital death is also death on demand: you can order a pizza or someone’s beheading, but only the latter is free.

Stills from a video no longer available at islammemo.cc.

Stills from a video no longer available at islammemo.cc.

Death documented, filmed, scripted. There’s an aesthetics of digital death born out of repetition: different angles, the recurrence of certain facial expressions, animal howls, pixelation, camera jumps. Different genres: people filming other people being killed for the camera, people killing other people, people filming already dead people, people filming their own deaths. A register of every wound, every shot, every severed head or limb removed from its trunk. Mass produced and streamlined for the audience, who have grown so accustomed to these necroaesthetics that they barely even flinch when someone’s brains end up against a wall. Experts: read the bottom half of any of these videos, the detachment, the lack of empathy, the dark jokes, The Ranking of Shocking Deaths. We haven’t all been that audience but we have all been loitering around the dark side of the internet, asking ourselves how far are we willing to go? How much curiosity is too much? How much can we desensitise ourselves? There you go, someone else has just been beheaded. Are you willing to watch?

From Ciudad Juárez to Raqqa, from New York to South Africa, the corpus of death on camera expands day by day. It would be possible to write an alternative history of the 20th and 21st centuries just by looking at its evolution, at the way its aesthetics have been bumped with the arrival of digital technologies, the way each one of these moments of death are received. As the cameras multiply, as the catalogue of the visible extends to the infinite, the victims continue to walk into the spectacular abattoir. We are destined to reach the moment where every death has its visual counterpart. Until even digital images turn to dust, or until there is nobody else left to watch.

—Fernando Sdrigotti

.

Fernando Sdrigotti is a writer, cultural critic, and recovering musician. He was born in Rosario, Argentina, and now lives and works in London. He is a contributing editor at 3am Magazine and the editor-in-chief of Minor Literature[s]. His new book Shetlag: una novela acentuada, has just been released by Araña editorial, Valencia. He tweets at @f_sd.

/

Wow. Capturing death–physical death………oh just has me thinking about spiritual death–a slow and agonizing one. Thanks for this.