It was through Phyllis Springer and Goksin Sipahioglu, the owners of the celebrated photo agency SIPA press in Paris, that I met Mavis Gallant. This was in the 1980s.

Mavis lived in the apartment next to Phyllis and Goksin on the left bank near Boulevard Montparnasse, not far from 27 rue de Fleurus. In that same apartment building in those days lived the Czech novelist Milan Kundera, with whom I had no encounter.

I had been staying in Paris above a couscous restaurant on rue Xavier Privas that I shared with fullback-sized cockroaches. In those days I drove a yellow deux chevaux I named Colette. I would park her where I could, changing places in a failed attempt to avoid parking tickets, but at least not being towed.

Some days I’d buy a lunch from un marchand de rue and, with a bottle of vin de pays, take my meal on Square du Vert Galant, a point on l’Ile de la Cité where I’d watch the bateaux mouches on the Seine. One such lunch I saw a barge going up the river packed with cars; Colette was among them—-in fact, on the bow, like a figurehead.

It took three days of my poor French and 300 francs to free her from the Fourrière, a kind of dog pound for cars. Later, just before I left Paris, I put an AV sign in the windshield and sold her to a sous chef of Café de Palais on Place Dauphine. Adieu: Colette.

Sometimes Phyllis and Goksin would invite me to join them for dinner at a restaurant where they were habitués. It was at one of those meals that I met Mavis: La Marlotte? Brasserie Lipp? Closerie des Lilas? Probably La Marlotte, as that was not far from where they all lived.

It was at that meal that Christiane Amanpour stopped to say hello to Goksin and Phyllis; she had worked for them at SIPA before she turned to television reporting.

—He is a great photographer, she said to me, putting her hand on Goksin’s shoulder. Do you know that? I said I did. And Mavis is a great writer, she continued. I said I knew that as well.

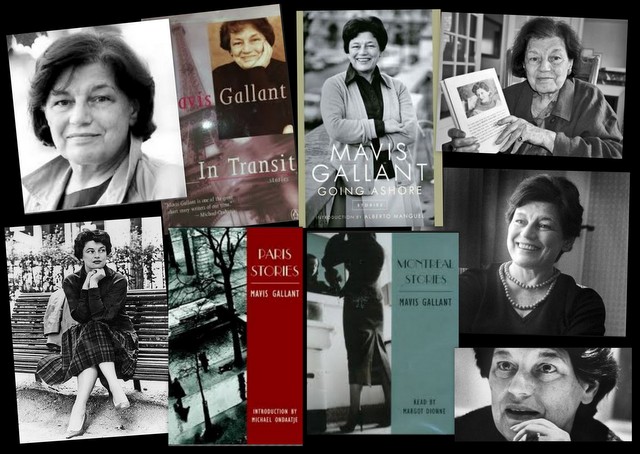

I had, like almost any American author who writes short fiction, read Mavis’s stories in the New Yorker. Along with Salinger and John Cheever in those days, you could earn multiple graduate degrees in creative writing by reading these authors. At one point I typed (on a manual typewriter, it was that long ago) parts of stories from all three to see what they had accomplished, and how they did it. I learned, among other things, what a fine sense of local detail these writers had: Salinger for the parks and subways of New York City; Cheever for the upstate suburbs with roaming lovers and Labrador Retrievers; Mavis Gallant for the rues of Paris; her stories were their own Plan de Paris.

Also at that first dinner, Phyllis asked Mavis if she had walked that day. Paris has many rainy days, and that had been one of them.

—I walk every day in Paris, Mavis said. It is how I fetch my stories. Not to do so would be impossible.

Years later, when she was crippled by arthritis and diabetes, Mavis’s agent made her a Christmas gift: a year’s worth of taxi rides so she could continue fetching her stories.

I imagine her with the notebook of her writer’s mind open through her eyes as she has the driver take her toward Place de l’Odéon, and then down where the students rioted in 1968. The next day the taxi is driving her across the Seine toward the Hotel de Ville in the 4th, past the apartment buildings and cafes and art galleries of her characters, and beyond: to Pere Lachaise in the 20th–all the time Mavis not looking where she had been in her previous work, but where in her mind’s eye she would be setting new stories once she got back to her writing.

In the years that followed our first dinner, Mavis and I would eat entre nous at restaurants that her characters and mine frequented; she would order from my fictional menu, and I would order from hers–both being true to our characters. Because of the writer she was, and because of the writer I was, her characters were much better fed than mine. Tant pis. At least I ate well, and in her company had bright and witty talk.

At one such lunch (at Le Cherche Midi I think because it was open on Sunday), she lectured me that I was not a writer because I did not make my living as one; beyond that, I taught creative writing, which is not how writers learn. I said I knew the latter from reading her stories. She smiled.

As if to compensate for her rather pointed points, she ordered a split of Chateau D’ay (the appellation delighted her given the company), and toasted the quality of my fiction: très amusant, which was high praise, as she thought herself a comic writer. Très belle: To Mavis Gallant, after all these years I toast both the woman and her fiction, as if the two can be separated which, had you watched her walking through Paris in the rain (as I did one day on my way to join her for lunch, her head turned here and there to see what would become the facts of her fiction) you know is, thankfully, impossible.

—Robert Day

Robert Day’s new novel Let Us Imagine Lost Love premiered here on Numéro Cinq in its entirety as a serial novel and will be published in fall 2014 by Mammoth Publications. Prior to that, his most recent book was Where I Am Now, a collection of short fiction published by the University of Missouri-Kansas City BookMark Press. Booklist wrote: “Day’s smart and lovely writing effortlessly animates his characters, hinting at their secrets and coyly dangling a glimpse of rich and story-filled lives in front of his readers.” And Publisher’s Weekly observed: “Day’s prose feels fresh and compelling making for warmly appealing stories.”