First, a few disclaimers: My knowledge of the history of Italian poetry is limited. There is Dante’s Divine Comedy, which I studied reluctantly in college and have only grown to appreciate over the years, especially the brave and foolish translations that try to bring Dante’s terza rima forward from rhyme-rich Italian into rhyme-impoverished English. After Dante there is…let’s see…Petrarch and his sonnets, with their non-Elizabethan rhyme scheme, and… Boccaccio was a poet, wasn’t he? But all I remember of Boccaccio is that he wrote The Decameron, and those are stories written in prose.

At this point I have to jump from the Middle Ages up to the 1800’s – there was an Italian poet named Leopardi, but I know nothing about him, only his name and that he lived around the time John Keats lived. There it is: in one jump, five centuries of Italian poetic tradition lost to me. In the 1900’s there was someone named Campana – or was Campana Spanish? No, Italian, I think. And there was definitely a modern Italian poet named Ungaretti but I’ve never read his work – or was Ungaretti a woman? No, a man, I’m sure. I remember thinking his name sounded like an expensive espresso machine.

So in writing about Eugenio Montale, a Nobel-Prize-winning poet few North Americans have heard of, I admit freely that I am not a fluent guide, only a fan. I don’t know the traditions that his work springs from.

I do know he was born in Genoa in 1896 and died in Milan in 1981. Growing up, he spent holidays with his large family in Monterosso, one of the Cinque Terre villages which hangs dramatically from the cliffs of Liguria, a landscape that shows up literally and metaphorically in much of Montale’s poetry. I know he had a contentious relationship with Ezra Pound, who was arrested for treason after a pro-Fascist stint as a radio broadcaster in Mussolini’s Italy (Montale was famously anti-Fascist, forced from his job after refusing to join the Fascist Party.)

In preparation for this look at Montale’s work, I consistently ran up against the term “hermeticism” to describe his circle of poets. Hermeticism? And specifically Italian hermeticism? The term was tossed around casually enough and linked to French surrealism, but I had to go to the Encyclopedia Britannica for a solid definition (“…modernist poetic movement originating in Italy in the early 20th century, whose works were characterized by unorthodox structure, illogical sequences, and highly subjective language.”) In other words, the poet locks himself into his poems and leaves the reader out. Since I disagree with that assessment of Montale’s poems, I don’t believe it’s the reason behind why the poet is not well-known here.

One credible reason might be his late-in-life pessimism, seldom far from the surface. In fact, his Nobel Prize lecture is not the most optimistic of speeches, ending on this downbeat note: “It is useless then to wonder what the destiny of the arts will be. It is like asking oneself if the man of tomorrow, perhaps of a very distant tomorrow, will be able to resolve the tragic contradictions in which he has been floundering since the first day of Creation….” Poets with a reputation for pessimism are not embraced warmly by the general public. (As counterbalance to this reputation, try the charming video at this link, which shows Montale having a great time with an interviewer, then reading a section of Ossi de seppia which begins, “Forse un mattino andando in un’aria di vetro, /arida, rivolgendomi, vedro compirsi il maracolo….” (Maybe one morning, walking in air / of dry glass, I’ll turn and see the miracle occur….”

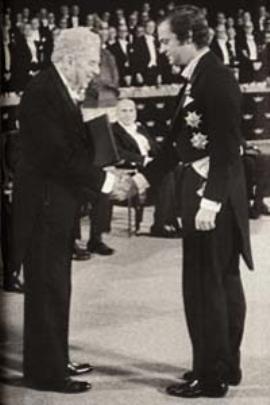

Montale receives the Nobel Prize from the King of Sweden

Montale receives the Nobel Prize from the King of Sweden

Another contributing factor to his lack of popularity here is this: Even North Americans who love poetry – and practice it – are sadly uninformed about individual poets (and whole schools of poetry) beyond their borders, including poets who have achieved fame at a broad international level. Is it the fault of our insularity – an ocean wide and deep at each edge of our “sea to shining sea” – and of our misguided sense of exceptionalism in general? Maybe the triumph of English as a global language has become a linguistic substitute for the defunct geographical concept of Empire. If that’s true, we can claim our ignorance is due in part to our superiority – an oxymoronic (and ridiculous) conclusion. Or maybe our educational system simply fails us, and we are left with wide swaths of ignorance in certain areas, including the learning of foreign languages to begin with. Maybe I shouldn’t even say maybe to that.

There’s one more possibility I can think of, a more attractive one which does less finger-wagging and makes me less embarrassed by gaps in my education, and that is the one Robert Frost offered: “Poetry is what gets lost in translation.” If we accept the idea that the key element which distinguishes poetry from prose is its musicality (and not just those line breaks) then we have to accept the idea that translations which cannot capture the cadences of the original are, to a certain extent, failures. As Iris Murdoch said after being questioned by someone about her translations of French poetry, “The activity of translation…turned out to be an act so complex and extraordinary that it was puzzling to see how any human being could perform it.”

Adequate literal translations – yes, those are possible. Brave attempts to reproduce formal elements – rhyme and meter – and make them work alongside the literal translation? Yes, those exist and are laudable. But can we ever hear and know, at a visceral level – heartbeat and hoofbeat – the effect of a poem whose original language is not our own? I’m not sure. I suspect not. And maybe it is this – translation’s intrinsic failure – that makes us avoid poetry written in other languages. Vladimir Nabokov said it well in his poem “On Translating Eugene Onegin”: Reflected words can only shiver / Like elongated lights that twist / In the black mirror of a river / Between the city and the mist.

Which brings me back to my reading of Eugenio Montale, the great Italian poet of the 20th century, whose translated poetry deserves to be much more widely read, but whose name usually evokes the response “Who?” His poems seem to me to be filled with music. Though I don’t speak Italian, I do speak Spanish, and I’ve always thought that the Latinate origins of those two languages helped me in my reading of Montale. But is my sense of its musicality justified?

Here is the original Italian of one of his most famous poems, published in his first poetry collection, Ossi di seppia (“Cuttlefish Bones”), in 1925. The English translation follows. To my ear (as I imagine it read aloud by someone who speaks fluent Italian) it sounds like river water rippling around well-polished rocks:

I Limoni

Ascoltami, i poeti laureati

si muovono soltanto fra le piante

dai nomi poco usati: bossi ligustri o acanti.

lo, per me, amo le strade che riescono agli erbosi

fossi dove in pozzanghere

mezzo seccate agguantanoi ragazzi

qualche sparuta anguilla:

le viuzze che seguono i ciglioni,

discendono tra i ciuffi delle canne

e mettono negli orti, tra gli alberi dei limoni.

Meglio se le gazzarre degli uccelli

si spengono inghiottite dall’azzurro:

più chiaro si ascolta il susurro

dei rami amici nell’aria che quasi non si muove,

e i sensi di quest’odore

che non sa staccarsi da terra

e piove in petto una dolcezza inquieta.

Qui delle divertite passioni

per miracolo tace la guerra,

qui tocca anche a noi poveri la nostra parte di ricchezza

ed è l’odore dei limoni.

Vedi, in questi silenzi in cui le cose

s’abbandonano e sembrano vicine

a tradire il loro ultimo segreto,

talora ci si aspetta

di scoprire uno sbaglio di Natura,

il punto morto del mondo, l’anello che non tiene,

il filo da disbrogliare che finalmente ci metta

nel mezzo di una verità.

Lo sguardo fruga d’intorno,

la mente indaga accorda disunisce

nel profumo che dilaga

quando il giorno piú languisce.

Sono i silenzi in cui si vede

in ogni ombra umana che si allontana

qualche disturbata Divinità.

Ma l’illusione manca e ci riporta il tempo

nelle città rurnorose dove l’azzurro si mostra

soltanto a pezzi, in alto, tra le cimase.

La pioggia stanca la terra, di poi; s’affolta

il tedio dell’inverno sulle case,

la luce si fa avara – amara l’anima.

Quando un giorno da un malchiuso portone

tra gli alberi di una corte

ci si mostrano i gialli dei limoni;

e il gelo dei cuore si sfa,

e in petto ci scrosciano

le loro canzoni

le trombe d’oro della solarità.

William Arrowsmith is probably the best known translator of Montale’s work, but the following English translation of “I Limoni” is by poet Lee Gerlach (who also deserves to be more widely read.) I prefer it especially for that wonderful turn of phrase “the jubilee of small birds,” which Arrowsmith translates as “the gay palaver of birds”:

The Lemon Tree

Hear me a moment. Laureate poets

seem to wander among plants

no one knows: boxwood, acanthus,

where nothing is alive to touch.

I prefer small streets that falter

into grassy ditches where a boy,

searching in the sinking puddles,

might capture a struggling eel.

The little path that winds down

along the slope plunges through cane-tufts

and opens suddenly into the orchard

among the moss-green trunks

of the lemon trees.

Perhaps it is better

if the jubilee of small birds

dies down, swallowed in the sky,

yet more real to one who listens,

the murmur of tender leaves

in a breathless, unmoving air.

The senses are graced with an odor

filled with the earth.

It is like rain in a troubled breast,

sweet as an air that arrives

too suddenly and vanishes.

A miracle is hushed; all passions

are swept aside. Even the poor

know that richness,

the fragrance of the lemon trees.

You realize that in silences

things yield and almost betray

their ultimate secrets.

At times, one half expects

to discover an error in Nature,

the still point of reality,

the missing link that will not hold,

the thread we cannot untangle

in order to get at the truth.

You look around. Your mind seeks,

makes harmonies, falls apart

in the perfume, expands

when the day wearies away.

There are silences in which one watches

in every facing human shadow

something divine let go.

The illusion wanes, and in time we return

to our noisy cities where the blue

appears only in fragments

high up among the towering shapes.

Then rain leaching the earth.

Tedious, winter burdens the roofs,

and light is a miser, the soul bitter.

Yet, one day through an open gate,

among the green luxuriance of a yard,

the yellow lemons fire

and the heart melts,

and golden songs pour

into the breast

from the raised cornets of the sun.

As much as I admire this translation, it’s clear that the music in the first stanza alone – the long “e” rhyme of all those internal and end-line words (ascoltami, i, poeti, laureati, si, nomi, usati, bossi, ligustri, acanti, erbosi, fossi, ragazzi, i, ciglioni, ciuffi, negli, orti, gli, alieri, limoni) has been lost. Does Gerlach’s free-verse English have a subtle music of its own? It does (“Tedious, winter burdens the roofs, / and light is a miser, the soul bitter.”) But does this evoke, much less reproduce, the music of the original? Can we say we understand what Montale does with sound in his poem by reading this translation? No.

“…the yellow lemons fire / and the heart melts….”

“…the yellow lemons fire / and the heart melts….”

In fact, the more aggravating question might be this: Do we understand the sound register of the original at all? Or do we romanticize the Romance languages, pleased by their multisyllabic flow, believing them to be mellifluous just because we are accustomed to the monosyllabic chunks of granite that English inherited from its Anglo-Saxon ancestors? Montale himself felt his native tongue was weighed down by exactly what I take to be its quickness and its flow, saying once that he fought “to dig another dimension out of our heavy, polysyllabic Italian.” One critic I read said he would have to go all the way back to Dante to hear an Italian poem as guttural as “I Limoni” (specifically referring to the doubled consonants in many of the Italian words.)

Guttural? That surprised me as much as the word “hermetic” did when applied to a poem which feels so wide open, accessible, and generous-hearted. Maybe “guttural” in this case suggests a sprung rhythm I can’t quite hear, in the style of Gerard Manley Hopkins, whom Montale read and was influenced by. If so, the translation provided here fails in a more serious way, since Hopkins (“fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings, / landscape plotted and pieced—fold, fallow and plough….”) is nowhere to be found in it. I’ve wondered at the translatability of Hopkins – Montale was only one among others who attempted to translate the English poet into Italian, a formidable task considering Hopkins’ penchant for vocabularies and phrasings that were Germanic.

There might be poets who are singularly unsuited to translation into particular languages. And maybe the whole idea of what is “lost in translation” has less to do with poetry and more to do with cultural constructs in general; that is, maybe the failure of some translations (“Translation is the art of failure,” said Umberto Eco) is not only a failure of sound reproduction but of emotional connotations, linguistic anomalies and cognitive connections. The way we think (and so, the way we hear and process language) is determined by our mother tongue. It’s enough to make a translator throw in the towel – but thank goodness, some do not. If translation is our only access to certain poets, isn’t a flawed attempt better that no attempt at all? For anyone who wants to explore issues of translation more deeply, try reading Douglas Hofstadter’s quick essay, “What’s Gained in Translation,” as a teaser to get you interested in his doorstop-size book, Le Ton Beau de Morot: In Praise of the Music of Language.

In any case, I don’t hear Hopkins in Montale’s “I Limoni.” And I can’t quite see the “obscure” nature of Montale’s poems that so many critics moan about. Yes, his poems are deeply personal. No, his frame of reference is not everyone’s – it includes his wife, his lovers, a landscape (Liguria) we are not completely familiar with, and politics that we are only marginally aware of. Montale was a firm anti-Fascist, and some of the allusions in the poetry will go over the heads of people unfamiliar with how those political issues played out in Europe during the 1930’s and 1940’s. We have to pause and hunt a bit to understand a few of the references. Easy, no. But “characterized by unorthodox structure [and] illogical sequences” as the Encyclopedia says? I don’t see it.

Maybe this is just a case of a poet’s work being ahead of its time, in the way paintings by Paul Klee might have seemed indecipherable to those who loved Monet. To put it in a more contemporary frame, maybe people two generations out will be reading the work of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets and wondering why people (me, for example) once thought of them as non-linear, illogical and difficult. It pleases me to think that the critics might be wrong about the “difficulty” of Montale’s work. As the poet himself once said, “I have never purposely tried to be obscure and therefore do not feel very well qualified to talk about a supposed Italian hermeticism, assuming (as I very much doubt) that there is a group of writers in Italy who have a systematic non-communication as their objective.”

My goal is not to argue with literary critics but to encourage the reading and enjoyment of Montale’s work. You don’t have to figure out whether his poetry is fluid or guttural, emotionally open or hermetically sealed. It’s intriguing and worthwhile, no matter what labels are attached to it. I am all for reading any poet who calls nature “rough, scanty, dazzling” and who says, “I wanted my words to come closer than those of the other poets I’d read. Closer to what? I seemed to be living under a bell jar, and yet I felt I was close to something essential. A subtle veil, a thread, barely separated me from the definitive quid. Absolute expression would have meant breaking that veil, that thread: an explosion, the end of the illusion of the world as representation. But this remained an unreachable goal. And my wish to come close remained musical, instinctive, unprogrammatic. I wanted to wring the neck of the eloquence of our old aulic language, even at the risk of a counter-eloquence.”

Montale published only five books in fifty years of writing, so he was not prolific. I’ve brought this up previously as one possible cause for poets being under-appreciated, though the spacing of books is less the issue here than the suspicions we all have about translation in general. But consider the lovely English translation (by William Arrowsmith) of “Il fuoco e il buio” :

Fire and Darkness

At times, because of dampness,

gunpowder fails to flash, and sometimes

catches without matches or flint.

A pocket lighter with one drop

of fluid could do the trick. And anyway

there’s no need for fire at all,

indeed, a good sub-zero curbs

that boring great-grandmother, Inspiration.

She was none too spry a few days ago

but she managed to disguise her wrinkles.

Now, ashamed of herself, she seems

to be skulking in the folds of the curtain.

She’s lied too often, now let darkness,

void, nothingness fall on her page.

Rely on this, my scribbling friend:

Trust the darkness when the light lies.

If you have only one book of Montale’s work on your shelf, it should be The Collected Poems of Eugenio Montale 1925-1977; the entire collection is translated by William Arrowsmith. It’s still possible to get the poems in individual volumes: Ossi di seppia (“Cuttlefish Bones”), Le Occasioni (“The Occasions”), La Bufera e altro (“The Storm and Other Things”), Xenia and Satura; it’s interesting to see how different translators handle the original Italian (poets Charles Wright and Jonathan Galassi take on the task with different collections, and Ghan Singh both translates and analyzes Montale’s work.) But The Collected Poems, set out in the chronological order in which the poems were published, offers both Italian originals and English translations (on facing pages for easy comparison) and it is carefully indexed with both Italian and English titles of poems, making individual poems easy to find. The real genius of this collection for anyone interested in translation is the section containing William Arrowsmith’s notes – 107 pages of them in a 793-page book. In an age where translators rarely get any public recognition for their work other than their names in smaller-than-average font on the title page, that kind of permission given the translator – to go into the particular nuances of translation and the frame of reference of the original – is exhilarating. As poet and critic Rosanna Warren says in her introduction to the collection, “In each phase, [Montale] invented new ways of putting poetic language under stress and of realigning poetry with prose.” Warren, by the way, goes on to praise Arrowsmith for what she calls his “idiomatic, surging versions, ever alert to the pull and swerve of the original.”

Here’s one more small poem to pull you Montale’s direction:

My Muse

My Muse is distant: one might say

(and most have thought it) that she never existed.

But if she was my Muse, she’s dressed like a scarecrow

awkwardly propped on a checkerboard of vines.

She flaps as best she can; she’s withstood monsoons

without falling, though she sags a little.

When the wind dies, she keeps on fluttering

as though telling me: Go on, don’t be afraid,

as long as I can see you, I’ll give you life.

My Muse long since left a store room

full of theatrical outfits, and an actor costumed by her

was an actor with class. Once, she was filled

with me and she walked proud and tall. She still has

one sleeve, with which she conducts her scrannel

straw quartet. It’s the only music I can stand.

For all his insistence on the inadequacy of language to capture the true essence of anything (he called it “inexpressibility”) Montale managed to use the tools of language with grace, clarity and power.

— Julie Larios

Julie Larios is the recipient of an Academy of American Poets Prize, a Pushcart Prize for Poetry, and a Washington State Arts Commission/Artist Trust Fellowship. Her work was chosen for The Best American Poetry series by Billy Collins (2006) and Heather McHugh (2007) and was performed as part of the Vox series at the New York City Opera (2010). Recently she collaborated with the composer Dag Gabrielson and other New York musicians, filmmakers and dancers on a cross-discipline project titled 1,2,3. It was selected for showing at the American Dance Festival (International Screendance Festival) and had its premiere at Duke University in July, 2013. For five years she was the Poetry Editor for The Cortland Review, and her poetry for adults has been published by The Atlantic Monthly, McSweeney’s, Swink, The Georgia Review, Ploughshares, The Threepenny Review, Field, and others. In addition, she has published four books of poetry for children. She lives in Seattle.

Dear Julie,

Thanks so much for this delightful essay, at once unassuming and richly informed. You provide some lovely poems, insightful thoughts on translation, and inspiration to read Montale in depth. Two minor notes: a typo to be corrected in stanza 3 of “The Lemon Tree” (You[r] mind seeks”); and I suspect that the odd but accurate “scrannel” in the final poem is borrowed by Arrowsmith (or Montale?) from Milton’s “Lycidas.”

Pat Keane .

Thanks, Pat. Typo has been corrected, and I appreciate the explanation about Milton’s use of “scrannel” (meaning thin and harsh in the sense of scrawny and scrappy….) I love the idea of a scrawny muse!

Milton’s use of the word “scrannel” brings in the image of straw, too –

What recks it them? What need they? They are sped;

And when they list their lean and flashy songs

Grate on their scrannel pipes of wretched straw,

The hungry sheep look up, and are not fed….

Good catch, Pat – and it seems to be even more proof that what we lose (or gain) in translation includes the reverberation of particular words put into a cultural context.

Bravissima, Julie! I’ll return to this essay (and Montale’s poems) again soon, I’m certain. I speak no Italian, but I long to teach my tongue to pronounce “il filo da disbrogliare che finalmente ci metta” and suchlike. For now I’ll console myself with lines like Montale’s/Gerlach’s “along the slope plunges through cane-tufts” and “from the raised cornets of the sun.” (A translation is a form of collaboration, I think.)

A poem can give us our birth language anew…so that we are not speaking or listening as we are accustomed to do. In some ways this compounds the troubles with translating. But it also tells us that every novel expression, no matter the language, is a renewal made of syllables.

Thank you!

Steven Withrow

Or perhaps just “a renewal of syllables.”