Passion may be the very essence of romantic love, as it is of art, thus Berthe and Mary’s torment becomes as vital to their overall happiness as pleasure. The lyricism with which Oliveira conveys this fact – in particular, through dialogue and narration – illustrates the dual nature of love, for instance when Mary and Degas share an intimate moment and she notices that “he smelled of graphite and oil and turpentine; he smelled of work, of Paris, of all of art, everything she wanted.” —Laura K. Warrell

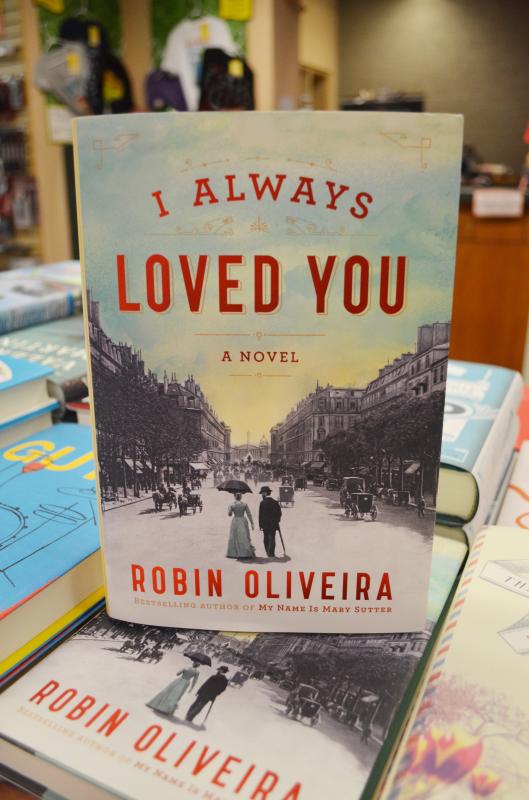

I Always Loved You

A Novel

Robin Oliveira

Penguin, $27.95

In a literary culture where explorations of romance are often relegated to lightweight, Hollywood–ready love stories with contrived happy endings, Robin Oliveira distinguishes herself. Her latest novel, I Always Loved You, is romantic in the truest, most intellectually compelling sense of the word. The narrative travels elegantly across the topography of love while simultaneously exploring the agony and exultation of the human experience as it manifests in life and art. The relationship between artists Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas sits at the center of this novel set amongst the salons and exhibition halls of Belle Époque Paris, which means Oliveira has given herself a challenge unique to writers of historical fiction: faithfully representing a time and cast of characters readers know well while also telling a story that is fresh and contemporary. Oliveira meets this challenge masterfully while also creating an air of romance too often missing in modern fiction.

This is Oliveira’s second novel. Her first, My Name is Mary Sutter, won the James Jones First Novel Fellowship, while she was writing it, and the Michael Shaara Prize for Excellence in Civil War Fiction after it was published. I Always Loved You is a story about another strong-willed Mary forced to find her way in male-dominated society. Oliveira considers women’s struggles among men as “one of the unifying conflicts across cultures,” one which she likes to showcase in her work.

Indeed, Mary Cassatt was a quintessential woman of courage. Not only did the young American painter uproot her life in Philadelphia to relocate to Paris alone, but she also managed to become one of the only women to exhibit alongside the likes of Degas, Manet, Monet and Pissarro. In I Always Loved You, Cassatt is presented as a headstrong female who bends to no man’s will and even overwhelms her male counterparts with her pluck. After Degas introduces her to the impressionists at a salon, Mary realizes “what it was to be a woman at a party in Paris. One either fed the men or was consulted about the time, but was not expected to speak beyond pleasantries.” She asserts herself by openly disagreeing with Émile Zola’s views on literature versus art, suggesting the writer’s work is “less vivid” than Degas’ paintings, then watches as Zola’s “wine-flushed face blushed an even deeper shade of vermillion.”

But it is her friendship with Degas that constitutes the greatest conflict of Mary’s life. Though the true nature of the artists’ relationship remains a mystery to this day – Cassatt burned all of their correspondence – Oliveira places them in a will-they-or-won’t-they love affair in which Mary’s desire for Degas occasionally surpasses her desire to create art, while Degas’ obsession with his work drives the lovers together and apart for years.

The novel begins in 1926 after Degas has died and Mary is sorting through boxes of old letters made up of “so many pages, you would think they had been in love.” The narrative then steps back to 1887 after Mary has returned to Paris to build a life having studied briefly in the city the year before. She attends a salon with her friend Abigail Alcott, sister of Louisa May, where unbeknownst to her, she is ogled by Edgar Degas. Unbeknownst to Degas, this attractive woman is Mary Cassatt whose painting he admired weeks before at an exhibition.

Later, an introduction by a mutual friend seals their shared destiny. Mary asks Degas, whose work she also admires, whether he believes art is a gift, to which he replies, “Art does not arise from a well of imaginary skill, obtained by dint of native ability…Art is earned by hard work, by the study of form, by obsessive revision. Only then are you set free. Only then can you see.”

This is the first in a lifetime of conversations about craft, and most interestingly the notion of “seeing,” in which the lovers engage, grow intimate and fight. Degas proves to be an unpredictable, argumentative cynic and wayward friend who nonetheless adores Mary and her work. He brings her into his circle of artist colleagues where Mary cuts through “the clannish nature of Parisians” with her challenge to Zola. Though her path to acceptance by the circle is bumpy, she eventually becomes an integral part of one of the most celebrated communities of artists and thinkers in Western history.

Through the course of the novel, Mary struggles with her muse and attempts to mold her art to the conventions of the time until Degas inspires her to stay true to her singular vision. In her creative life, she experiences great successes and humiliating failures, while in her personal life she struggles with her family, including a sick sister and disapproving father, who come to live with her in Paris. All the while, Degas flits in and out of her life, fawning over her one moment then maintaining his distance the next.

A subplot between Édouard Manet and painter Berthe Morisot, the wife of Manet’s brother Eugene, reinforces the novel’s overarching theme of elusive love. Manet and Morisot spend the novel stealing glances, sneaking away for trysts, smiting one another with jealous jabs and suffering the consequences of choosing fidelity to family over true love.

I Always Loved You is not romantic simply because it deals with matters of the heart, but because Oliveira adheres to many of the attitudes and aesthetic qualities of romanticism: an emphasis on the self and creative freedom, the elevation of the human soul and pursuit of wonder, the use of extravagant language to reflect the poetry of life and an acceptance, even glorification, of the agony of existence. The characters exemplify the romantic notion that pleasure, beauty, love, even artistic achievement requires pain to be meaningful and real.

Oliveira develops the romantic soul of the novel through the ideas and choices her characters make, and the lyricism with which she tells their stories. Degas acts as a champion for the self and the struggle for art over commerce. Several times during the course of the novel, he withdraws his work from exhibitions, even if it puts Mary and his friends in difficult positions, because he prioritizes the private experience of creation.

“Nothing public matters,” he tells Mary. “What matters is what happens inside the studio. Your work. That is where genius lies, where it is born…It is not born on the walls of an exhibition.”

Mary begins the novel striving for recognition outside of her studio but only discovers her individual style, and consequently finds success, once she heeds Degas’ wisdom, abandons the “academic values” set by the establishment and “renders a portrait she knew the Salon would undoubtedly reject.” Mary is blissful whenever inspiration strikes, but in true romantic fashion, also feels “a wash of sadness, for that sensation happened rarely for an artist, and was in turn fleeting.” Her work becomes as rewarding as it is “punishing,” just like her love for Degas.

Of course, love is at the heart of the novel, especially the love emotionally faithful women feel toward emotionally faithless men like Degas who is too egotistical to love. After a frustrated Mary asks him, “Do you love anyone, Edgar? Anyone at all?” Degas ponders the question; “Why not love her? Why not say it? What had quickened when he had kissed her had at least been lust. But he was not a romantic man.”

Meanwhile, Manet is simply a cad, parading his lovers in front of not only his loyal wife but Berthe, the woman he loves. Berthe is torn between a tempestuous affair with Manet and a dependable marriage to a devoted husband, who just happens to be Manet’s brother; “I have found a good man who will forgive me anything, even the gossip of others. Even the truth. What, then, was love? The incessant whisper of passion, or the tedious murmur of caring? The ragged tear at your heart, or the gentle caress that rendered you safe? Perhaps there was no one thing that was love.”

Passion may be the very essence of romantic love, as it is of art, thus Berthe and Mary’s torment becomes as vital to their overall happiness as pleasure. The lyricism with which Oliveira conveys this fact – in particular, through dialogue and narration – illustrates the dual nature of love, for instance when Mary and Degas share an intimate moment and she notices that “he smelled of graphite and oil and turpentine; he smelled of work, of Paris, of all of art, everything she wanted.” The exalted feeling with which the romantic lover relates to her mate is exemplified by such hyperbolic language: Degas does not simply smell like a man she loves but he smells like the world and everything in it Mary cherishes. When he disappears in the weeks following their intimacy, she thinks, “all things she would abandon at the slightest encouragement if he would only grasp her wrist or whisper, I missed you.” Oliveira’s novel lays bare the inherently romantic nature of elusive love, which makes lovers experience the ecstasy of union and the torment of loss again and again.

Likewise, the tragedy of unfulfilled love has greater consequence in a well-lived life than love fulfilled as suffering makes life meaningful. Mary, still smarting from the cruelty Degas has inflicted upon her, asks Berthe whether her relationship with Manet has been worth the pain. “Live without having loved?” Berthe answers. “I don’t know if I would have wanted that…I can’t help that I love him. I wish that I could, but no amount of wishing has made it so.’”

This romantic spirit is further accentuated by the presence of light, and by extension vision, as a recurring image in the novel. Light plays a major role in the evolution of the plot as these artists are inspired by, work by, covet and capture light, thus, it features heavily in their interactions with one another and their work. “‘I’ve visited your country,’” Degas tells Mary when they first meet. “‘The light was horrid.’” Later, the lovers see the light hitting the Seine a certain way and “longed for a brush to record it before it slipped away.”

Oliveira uses light to symbolize the characters’ internal experiences and artistic impulses. When Berthe’s father dies she agrees to marry Eugene because “all the light had gone out of the world” while a character in the midst of dying feels “the light trickling away.” Light finds its way into the novel through other words: glimmer, shimmer, glare, flickering, brilliant, luminous, reflect, brighten, candle, sunlight.

But Oliveira’s most stunning handling of light is how she uses it to tell her story the way her characters use it to paint. She manipulates the light in the rooms and streets to give texture to the scenes, for instance when Manet confesses to Berthe that he has contracted syphilis and the “dull light” outside the window makes “pale marble of his hands.” Oliveira uses light to signal changes in mood as well, like when Degas breaks the news to Mary that he has called off the publication of a journal they created together and “a cloud passed over the sun, casting a cool shadow over the lake, dulling the reflection of the trees in the water.”

In yet another scene, Mary has been weakened once again by Degas’ cruelty as “the glimmer of the candle [in the room] fading now, and with it all her vague dreams of a life lived beside this man…The flame trembled in its puddle of molten wax and went out, rendering the studio a place of shadows and depth.” These scenes are as provocative and beautifully rendered as the paintings the characters create.

Certainly, light enables one to see and when, in the beginning of the novel, Degas tells Mary she must learn to “see” in order to create great art, she becomes obsessed with clarifying her vision. Oliveira uses sight as powerfully as she uses light: Mary wonders if she “would she ever truly see” and later realizes in order to do so she must “unsee” everything she has known before, from her creative habits to her view of herself and the world.

“Paint what you see, paint what you love,” Degas tells her, suggesting that artistic vision and love are one in the same or are at least rooted in the same place in the human soul. Perhaps then it is no coincidence when Mary finally finds her way that Degas tells her, “You’ve painted love…You must never paint anything else. You have found it. Your obsession is love.” How ironic that Mary is able to paint love and Degas is able to see it in her work, yet they are unable to experience it together.

Even more ironic is the fact that both artists are going blind. In the beginning of the novel, Degas is being fitted for special eyeglasses because there is a hole in his vision casting dark shadows. Blindness has stolen from him “the mass of things, their shape-ness, their roundness, their solidity. Edges wavered and blurred and doubled until forms became hallucinating shape-shifters, liquid impersonators of what had once been reliable, immutable matter.” Once again, the richness of Oliveira’s narration paints a vivid picture of the world seen through the eyes of an artist.

Certainly, there is no way to know whether Oliveira’s portrayal of her characters and their relationships are completely faithful to history but in the end it doesn’t matter. I Always Loved You is an engaging read because the author has recreated a world of romance and color populated by characters whose challenges mirror those of modern times. But for all the characters’ musings about artistic integrity and creative freedom, perhaps the words spoken by Manet best capture the novel’s enduring message: “It is love, my frightened ones. Love.”

—Laura K. Warrell

Laura K. Warrell is a freelance writer living in Boston. She teaches writing at the Berklee College of Music and the University of Massachusetts Boston and is a July, 2013, graduate of the MFA program at Vermont College of Fine Arts. She has previously published both fiction and nonfiction in Numéro Cinq.