This is the hard lesson of Lolita; it is a monument to an awful existential truth: simply to be alive, in the face of the whole history of human suffering, requires a kind of insane fortitude. Lolita reminds us that while soldiers were dying in European trenches, Monet was painting lilies in his garden; that horror and beauty are cosynchronous; that for every fine sentiment, every sweet emotion, someone else pays in blood, and eventually we all get presented with the check. —Bruce Stone

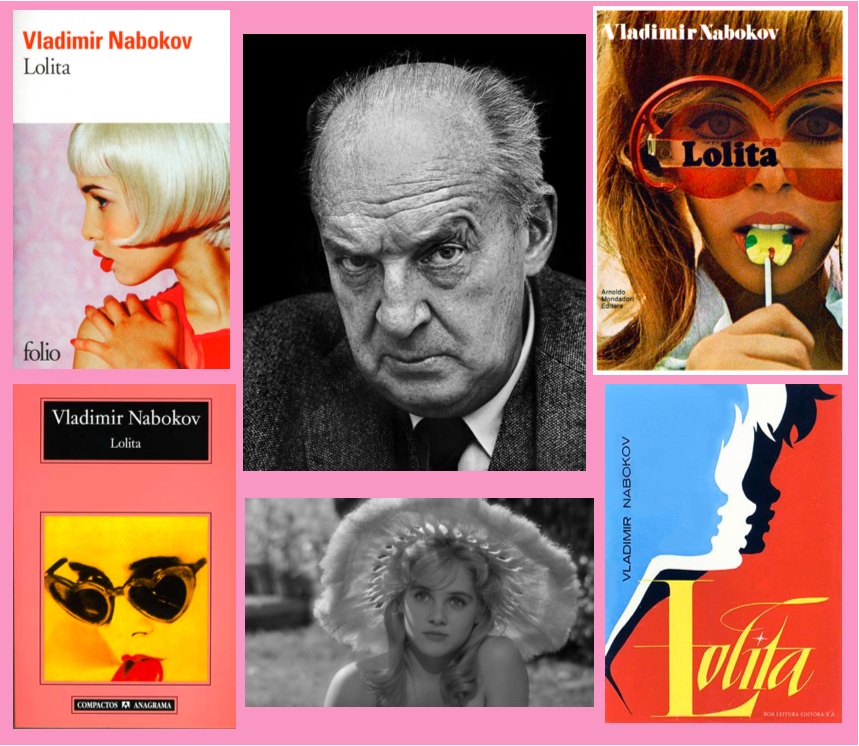

From the Stanley Kubrick film Lolita.

From the Stanley Kubrick film Lolita.

.

On March 19, the literary marketplace welcomed a new title by the young Vladimir Nabokov, who hasn’t been greatly inconvenienced by his death in 1977. The Tragedy of Mister Morn, a verse drama written in Berlin in 1924 and never published during Nabokov’s lifetime, reads as a kind of retread of Othello, set among the Bolsheviks: the plot points to Leninism, but the artifice is all Shakespeare, and the play’s release is timely on both counts. Six days earlier (a near eclipse of Morn’s arrival), the Erarta Museum in St. Petersburg, then hosting a performance based on Nabokov’s Lolita, absorbed the latest attack by the Orthodox Cossacks, a band of Russian conservatives that has been campaigning against Nabokov, denouncing his masterwork, since the start of the new year. Among the more serious incursions, a theater producer was beaten in January, but perhaps the most emblematic gesture was the lobbing of a vodka bottle through a window of the Nabokov museum: tucked inside the bottle, a note condemned Nabokov as a pedophile and warned of the imminence of God’s wrath.

Viewed as domestic terrorism (even Cossacks have dreams), these acts seem comparatively tame, even quaint. As a more benign kind of vandalism (tell that to the producer), they make their point clearly enough, I suppose. But as literary criticism, they are an utter travesty, an intellectual obscenity that should make the Cossacks and their kin themselves the object of public and lasting derision (pillories and tomatoes or, at minimum, raspberries). A half century has passed since Lolita’s publication, yet here we are again—it seems inevitable—with the literal-minded and the simpletons, the well-meaning zealots and zombie mooncalves breaking out torches and pitchforks, vodka bottles and spray paint, to decry Lolita as the work of the devil. Twenty-five years ago, in her appraisal of the novel, Erica Jong found this noise over its propriety exasperating, so maybe now more than ever, the only fit response to the Cossack charge is to ignore it, at most to repay the protesters with a bottle of one’s own, bearing just the terse rebuttal, “It’s art, stupid.” To do anything more, to defend Nabokov and his work more fully and forcefully, would be to concede that either needs defending in the first place.

And one would think that the Cossack claim could be made only by someone who hasn’t read the book. After all, unless you abuse the text pretty seriously (beat it within an inch of its life), it’s not possible to construe Humbert Humbert’s pathology as a behavioral recommendation. In this regard, his case is no different from that of multitudes of literary characters. Consider, for comparison, Brigadier Pudding in Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, who, for the sake of sexual arousal, eats the excrement of the book’s femme fatale as she is producing it (do the math for yourselves here). That the novel contains this character doesn’t mean that readers, or his creator, find this behavior appetizing. Unfortunately, the semi-literate Cossacks are not alone in their sentiments about Lolita, not the only hostiles in the field. In fact, their cause often finds support even from the ranks of Nabokov’s fans. In the 2009 BBC documentary How Do You Solve a Problem Like Lolita?, journalist and literary pilgrim Stephen Smith promises to resolve the title question, which he poses more bluntly at the outset: “was [Lolita] a morality tale or the fantasies of a dirty old man? [his grammar]” On the whole, the documentary feels like a superficial traipse through Nabokov’s life and work, a mercenary stoking of this combustible subject. But one vignette particularly rankles: Smith interviews Martin Amis, perhaps the most famous champion of Nabokov’s work, and here, as Amis glosses the prevalence of pedophilia in the Nabokovian catalog—which, indeed, spans (vestigially) from the very early stories to The Original of Laura, the unfinished last novel, published posthumously—his view of Nabokov bends sinister. He flatly concludes that this recurrent theme “distorts the corpus,” cropping up so frequently as to be an admission of guilt.

Scholars too, from time to time, have tried to paint Nabokov in these same colors, casting him as the pervy uncle in the house of literature. In 1990, in Texas Studies in Literature and Language, Brandon Centerwall attempted to deduce from the fiction that Nabokov himself was a victim of molestation, and subsequently a “closet pedophile.” The article is a textbook example of the biographical fallacy, a case study in bad reading (call it what it is, a masterpiece of stupidity), yet this line of attack was taken up once again in 2005, inflated to book length, by an Australian critic who elected to self-publish her treatise when the university presses balked. The book appears to be a work of character defamation masquerading as scholarship (a wonderfully scathing review, by Sarah Holland Batt, is available online), but should these academic insults seem a little dated and recherché, consider this incidental disclosure, the novel’s cameo appearance, in a New Yorker feature, from January of this year, on the treatment protocol for pedophiles. One of the men interviewed for the piece, who had as yet hurt no one, kept a secret list of child-pornographic art works, among which he numbered something called Lolita, which is hilarious, though he might have been referring to a film version. (I wonder if he has seen Hard Candy). The man had also jotted some notes to justify his erotic appetites—“Strictly speaking a girl between 13 and 17 is not a child”—and Cossacks will notice how these seem eerily akin to the pleas of Nabokov’s Humbert. No, the derogation of Nabokov and his Lolita is a doggedly persistent refrain, a vampire meme in the cultural memory.

Lately, I’ve been thinking that it might be necessary to entertain these charges against the writer—for the sake of argument, as a logical exercise—if only to shred them the more completely. It’s not just the prevalence or persistence of these attacks that compels me. Let me explain. In his very readable book, How Proust Can Change Your Life, Alain de Botton argues that the French writer’s masterpiece can subtly alter the reader’s own habits of cognition and perception. I take it for granted, as a given, that the same is true of Nabokov’s work: with its radiant precision, its richly patterned surfaces, its rampant serendipity, its rhapsodic and pulverizing prose, his fiction warps the mind in a most salutary way. In a thoughtful exchange on Slate, James Wood and Richard Lamb testify to the fact as they both complain of infection by Nabokov’s jeweled style. On a more tangible level, Nabokov’s work as a naturalist—his love for botanical things and butterflies which infuses his fiction—routinely inspires readers (not just me) to take up taxonomy, birdwatching, say, or tree identification: see Lila Zanganeh’s whimsical but skimpy hagiography The Enchanter: Nabokov and Happiness (2011), in which she reports that she too has found this element of Nabokov’s fiction contagious.

While Zanganeh chronicles a bit preciously her personal enamoration with Nabokov, David Kleinberg-Levin, a philosopher emeritus at Northwestern, advances more or less the same exalted argument; he attributes to the Nabokovian catalogue the full measure of the joy inherent in his own book’s title—Redeeming Words and the Promise of Happiness: A Critical Theory Approach to Wallace Stevens and Vladimir Nabokov (2012). (Clearly, the news hasn’t been all bad for Nabokov in the last few years.) Essentially, Kleinberg-Levin highlights two distinctive features of Nabokov’s fiction: its animated lexical surface (the prosody, cryptograms, puns and metamorphic words) and its narrative vanishing acts (in which worlds like a mad king’s Zemblan homeland are painted in lurid colors only to be razed, exposed as phantasmal and illusive, in which a Dreamer can stumble onto the set of Morn and remind the actors of their unreality). These features, for Kleinberg-Levin, evoke the awesome, originary power of language itself, its power to birth human consciousness, an experience conducive to, or synonymous with, happiness. Although his book is dense with reference and coiled academic prose, Kleinberg-Levin writes feelingly about the subject and is nearly convincing (I know he’s right, as is Zanganeh; I’m just not sure that there’s any rational way to argue the why). But here’s the rub: if sensible people are willing to ascribe a benevolent influence to Nabokov’s work, is it possible to dismiss out of hand, without a hearing, those concerns of the Cossacks and the demonizers that Lolita’s impact might be pernicious? That is, if books can be salutary, can they not also be toxic?

In his 1958 laudatory review of the book, Lionel Trilling inadvertently supplies the Cossack cause with this deadly ammunition; he writes that “in the course of reading the novel, we […] come virtually to condone the violation it presents.” The only outrage the work provokes, for Trilling, comes after the fact, when we recognize “we have been seduced into conniving in the violation, because we have permitted our fantasies to accept what we know to be revolting.” Trilling is mistaken in this conclusion, which is more a personal reaction than a reasoned response, but for Cossacks, I think it’s all the same anyway. That is, the Cossack argument makes no moral distinction between the author and his audience. The writer’s guilt is visited upon readers, museum curators, even by-standing sympathizers—everyone is smeared with the same graffitist’s brush—so it’s hard to know if influence, per se, counts among the novel’s offenses. Scholars like Centerwall, on the contrary, seem willing to allow that Nabokov’s moral hygiene isn’t necessarily identical to the reader’s, but if we grant to Cossacks this concern over influence—the novel’s ability to leave readers enlightened or benighted—it’s the Cossack position that seems the more dangerous of the two. For those of us who know better, this confusion of culpability actually has its advantages. It stands to reason, then, that if we can exonerate the reader, we have vindicated the author, or vice versa. But in the interest of coherent logic and simple commonsense, we might also distinguish between and treat separately these twin poles of accusation, to try to put the matter to rest. At the same time, I realize that this might be an impossible project: not that the controversy can’t be resolved, but that maybe it shouldn’t be resolved. Maybe Lolita is the shard of glass forever embedded in the flesh, the blade that never loses its edge, the trail of hot coals that perpetually smolders: maybe, when we reread it, as we must, we should feel the cut, let it scald, as if for the first time.

The Art of Self-Defense

After Lolita’s publication, Nabokov himself spent a good deal of time responding to the trumped-up charges against him, with inconsistent results. The interview transcripts assembled in Strong Opinions appear to be unassailable, pitch-perfect rejoinders to critics and demonizers. However, television seems to have been a less hospitable medium. In a 1958 interview for the CBC—last year, 3 Quarks Daily ran clips of the footage—Nabokov and the telegenic Trilling joined forces to discuss Lolita’s shocking content, and in that conversation, Trilling identifies perhaps the most scandalous thing about the novel: that it invites us to believe that Humbert’s love for his nymphet is authentic, that by the book’s end, it transcends the category of child rape. When Humbert meets Lolita for the last time, she is married (at seventeen), pregnant, a nymphet no more, and trying sensibly to shift for herself and her husband in their hard-luck life. Of the encounter, Humbert writes,

You may jeer at me, and threaten to clear the court, but until I am gagged and half- throttled, I will shout my poor truth. I insist the world know how much I loved my Lolita, this Lolita, pale and polluted, and big with another’s child, but still gray-eyed, still sooty- lashed, still auburn and almond, still Carmencita, still mine. … [E]ven if those eyes of hers would fade to myopic fish, and her nipples swell and crack, and her lovely young velvety delicate delta be tainted and torn—even then I would go mad with tenderness at the mere sight of your dear wan face, at the mere sound of your raucous young voice.

Trilling might be on to something here, but the book proves more equivocal. Besides the disconcerting adjectives preceding that “delta,” a long-running debate among Nabokov scholars is whether the book’s last nine chapters, including the final meeting with Lolita and the murder of Claire Quilty, ever really happen beyond Humbert’s imagination. More importantly for the moment, Nabokov’s own remarks in that interview might fuel the ire of his antagonists. He mentions, for example, that he and his Humbert differ in many things besides their views of little girls; particularly, he mentions Humbert’s inability to distinguish a hawkmoth from a hummingbird. You don’t have to be a Cossack to hear something tone-deaf in this comparison, a jarring collision of the incendiary (pedophilia) and the urbane (ornithology). As a result, viewers might find themselves trying to interpret the writer’s body language, which is by any measure ungainly as he slouches and slides on an unaccommodating sofa. Jasper Rees, in his review of Smith’s BBC documentary, does this too: although he seems largely to suggest that the charges against Nabokov are bogus, the controversy a non-starter, he ends his article by picking again at the scab of the debate with this sketch of the writer: “Asked by an interviewer if he’d ever known a girl like Lolita, the old man’s lizard eyes flickered, and just for a second the body language spoke as eloquently as anything Nabokov ever wrote in his adoptive tongue.”

These allegations also prompted Nabokov to respond, away from the cameras, in the more composed forum of this Russian-language poem from 1959 (the translation is Nabokov’s own):

What is the evil deed I have committed?

Seducer, criminal—is this the word

for me who set the entire world a-dreaming

of my poor little girl?

Oh, I know well that I am feared by people:

They burn the likes of me for wizard wiles

and as of poison in a hollow smaragd

of my art die.

Amusing, though, that at the last indention,

despite proofreaders and my age’s ban,

a Russian branch’s shadow shall be playing

upon the marble of my hand.

At first glance, the poem too makes for a poor defense of the writer’s character (smaragd?!). An unusually attentive Cossack might seize upon the fact that Nabokov can’t bring himself to use the more accurate “pedophile” as the relevant aspersion, and in the last stanza, again he seems to put on equal footing the weighty matter of censorship with the trivial matter of proofreading (which is the point, at least in part: I wonder if the word doesn’t also contain a pun, alluding to readers who seek in literature a kind of proof, a bedrock of actionable belief). However, upon reflection, the poem does in fact do more to clear Nabokov’s name than it first appears. In refusing to countenance directly the charges against him, in evading the subject (and the horror) of real-world pedophilia, he reveals that his only concern is his literary legacy, which will carry the day in the end (those last two lines envision a marble statue of Nabokov in the Russia from which he was exiled). That Nabokov can find his predicament “amusing,” that he figures his lifespan and historical progress in terms of typographical conventions (the “last indention” in the story of his legacy): this is suggestive of a callousness, an aesthete’s flint-heartedness, a narcissism so frosty that the writer can convert his flesh-and-blood hand without anguish into marble. But on some level, this very heartlessness is not a failing but a requirement if the artist is to create a work, any work, in which characters are made to suffer and perpetrate cruelty.

In his Afterword to the novel, “On a Book Entitled Lolita,” which has accompanied every edition since 1958, Nabokov offers his most thorough response to his critics, successfully deflecting those charges that Humbert’s obsession is traceable to the writer. He notes the differences between his Lolita and the conventions of pornography (child or otherwise): “in pornographic novels action has to be limited to the copulation of clichés. Style, structure, imagery should never distract the reader from his tepid lust.” Although this eminently sensible and widely available text has done little to quell the controversy, it points the way forward. Yes, to find the best defense of the novel, and the fullest exoneration of its author, we have to turn to the work itself, the story of its genesis and the skill in its artistry.

The Fine Art of Edification

Stephen Smith tries to do exactly this, consult the book to vindicate the writer, in his documentary (though he too is hamstrung by the medium). Referring back to his title question—morality tale or pervert’s fantasy—in the end, Smith comes down firmly on the side of the former reading, endorsing the book’s moral vision. He points to Humbert’s acknowledgement of his own crime, his theft of Lolita’s childhood, his gross violation of her body and her life, an access of conscience that blossoms toward the end of the tale:

Unless it can proven to me—to me as I am now, today, with my heart and my beard, and my putrefaction—that in the infinite run it does not matter a jot that a North American girl-child named Dolores Haze had been deprived of her childhood by a maniac, unless this can be proven (and if it can, then life is a joke), I see nothing for the treatment of my misery but the melancholy and very local palliative of articulate art.

Essentially, Humbert acknowledges the evil of pedophilia for what it is.

While Smith is right on some level—the book does powerfully indict Humbert for his crime—his conclusion rests too heavily on Humbert’s eleventh-hour repentance. In this regard, Smith would appear to share the view of John Ray, Jr., a fictional psychopathologist who pens the Foreword to Humbert’s manuscript confession. In that Foreword, Ray characterizes Humbert’s story as a “tragic tale tending unswervingly toward a moral apotheosis,” just as Smith does, but Ray, in my reading, is a pedantic clown, an incompetent alienist more prone to titillation perhaps than any of Nabokov’s real-world readers (he refers to men who “enjoy yearly, in one way or another,” exactly the crime that Humbert commits: that choice of verb and the cruel euphemism for rape that follows are unnerving). Further, Nabokov portrays Ray as unusually blinkered in that, on the point of Humbert’s redemption—that moment of his moral transfiguration, staged atop an allegorical hill from which he can deduce the extent of his crime—the text is, again, uncooperative. Though the scene arrives only on the novel’s penultimate page, Humbert’s presumed “apotheosis” actually takes place before he reunites with Lolita, and before he tracks to his lair and kills Quilty, the playwright and pornographer with whom Lolita makes her escape from Humbert. That is to say, the “apotheosis” doesn’t exactly cause him to desist (and, yes, murder appears to be the less objectionable of Humbert’s offenses).

Instead of relying on the authenticity of Humbert’s professed repentance, we should look elsewhere to catch the novel’s antipathy for his crimes, which indeed is inscribed much more thoroughly and pervasively in the text. The book reveals most clearly that the nympholept’s paradise is painted in the colors of hell flames, from first to last; in fact, Humbert’s manuscript confession is more a record of the frustration and cauterization of his desires than a chronicle of their satisfaction. In one example, Humbert rents a new home in voyeuristic proximity to a school yard, but immediately, some construction workers arrive and start building a wall which they leave forever unfinished only after they have completely obstructed Humbert’s view. Elsewhere, he offers a passing sketch of his criminal lust in which Lolita is completely uninvolved, picking her nose and reading the newspaper, while Humbert clings desperately to his fantasy of tenderness, his invented image of the dream girl. It might be in the portrait of Quilty, Humbert’s nemesis, that we catch the most scathing indictment of the sexual predator. In Quilty we see the leering and lecherous monster, as Humbert describes him poolside, “his naval [sic] pulsating, his hirsute thighs dripping with bright droplets, his tight wet black bathing trunks bloated and bursting with vigor where his great fat bullybag was pulled up and back like a padded shield over his reversed beasthood.” The irony here is that Quilty’s beastliness is the very image of Humbert’s own evil; Humbert observes not his adversary and enemy, but his double, and notably then, it is this figure that Humbert destroys (if only metaphorically) in the novel’s last chapters.

The grotesque description of Quilty should make clear another point about Lolita: the mode and mood of the book is parody. In its blood and bones, the novel is a lampooning of any number of literary subgenres: the confession, the psychological case study, the murder-mystery, the doppelganger tale, even the fairy tale. As a result, neither Humbert nor Quilty offers a naturalistic portrait of a pedophile—these are parodies of pedophiles, unusually animated, expressive and convincing caricatures but still caricatures, their monstrosity and their manipulative charms (such as they are) intensified and distorted, to comic effect. No, to catch the real-life portrait of the pedophile, to isolate the type, I think we would have to consider Jerry Sandusky, the shambling dufus, a creepy lummox with an overbite incapable of formulating the extent of his own evil. Readers are welcome to quibble here, pointing to hyperliterate pedophiles in the historical record, but Humbert is a blow-up bogeyman, a balloon-animal of a pedophile that everywhere leaks air. When he makes his explicit defense of pedophilia as a cultural practice, readers can’t miss the irony that undercuts his pleas and renders the entire effort self-defeating and incriminating. While cataloging the historical prevalence of pedophilia, for example, he refers to the sexual mores in “East Indian provinces,” saying “Lepcha old men of eighty copulate with girls of eight and nobody minds.” Those last three words are crucial, charged with a blistering irony; to state that “nobody minds” is to offer a coded acknowledgement that something transgressive, patently wrong is at issue, and the trite colloquialism of the phrase, its chummy tone, is entirely incompatible with the heinousness of the subject. Humbert’s purported self-defense is routinely punctured with this kind of recrimination—and the net effect is hilarious, morbidly, unforgivably hilarious, maybe, but all the more sublime for being so.

The comedy itself in Lolita speaks volumes in defense of the author. See Humbert’s ludicrous description of his perceived competition for Lo’s affection, “two gangling, golden-haired high school uglies, all muscles and gonorrhea.” See how his extravagant ogling of the girl inspires the outburst, “oh, that I were a lady writer who could have her pose naked in a naked light!,” which is immediately undercut by authorial laceration, “But instead, I am lanky, big-boned, wooly-chested Humbert Humbert, with thick black eyebrows and a queer accent, and a cesspoolful of rotting monsters behind his slow boyish smile.” Again, I’m no expert in criminal psychology, but it seems to me that an actual pedophile would be incapable of making his avatar such a buffoon, his lust such a sadomasochistic farce. For Nabokov, laughter, rather than rage or righteous indignation, appears to offer the best defense against monsters and tyrants. As he wrote in arguably his best short story, “‘That in Aleppo Once…’” (1943), in reference to the Nazi horrorshow that claimed the life of his own brother, “with all her many black sins, Germany was still bound to remain forever and ever the laughingstock of the world.” This mature insight finds expression as well in the early Tragedy of Mister Morn, whose philosopher-king succumbs to belly-laughs even while trading punches with a rival.

This isn’t to say that Humbert’s narration isn’t often poignant, or that the novel lacks gravitas. Humbert is a skilled poet of his own pain, converting his agonies into art, and Nabokov allows him to express something of the purported rapture and the corresponding regret that inhere in his crime. After a run-in with Quilty inflames his jealousy, Humbert describes how he “ushered [Lolita] into a little alley half-smothered in fragrant shrubs, with flowers like smoke, and was about to break into ripe sobs and plead with her imperturbed dream in the most abject manner for clarification, no matter how meretricious, of the slow awfulness enveloping” him. Beyond this local and misdirected experience of rue, elsewhere, he records the “smothered memories” that emerge as “limbless monsters of pain,” “icebergs in paradise” in which his lust is interwoven with “shame and despair.” The beauty of Humbert’s lament might best be captured in this passage, in which he contemplates his fatal error: “it struck me that, quite possibly, […] behind the awful juvenile clichés, there was in her a garden and a twilight and a palace gate—dim and adorable regions which happened to be lucidly and absolutely forbidden to me, in my polluted rags and miserable convulsions.” True, Nabokov has the gall to render the concrete particulars that vivify Humbert’s lust—the portrait less a high-fidelity recording than a Warhol lithograph, garish and overexposed—but he does ensure that Humbert is tortured, deservedly, for his crime. If readers experience a measure of empathy for Humbert, it’s only because Nabokov allows us to see him as both villain and pathetic victim of his own delusions. (In this last, the Cossacks share Humbert’s predicament as surely as anyone who is led into violence by the force of belief—not a bad summary of the human condition).

Not surprisingly, Nabokov himself offers the most apt assessment of Humbert’s character in the Foreword to one of his earlier novels, Despair; he compares the two comparable narrators and concludes, “there is a green lane in Paradise where Humbert is permitted to wander at dusk once a year, but Hell shall never parole Hermann.” Yet, even if it’s clear that Nabokov himself is on the side of the angels in Lolita, this way of framing the debate, at its root, seems to me potentially self-defeating. After all, the novel itself anticipates this need for moral vindication. To that end, Nabokov outsources to John Ray, Jr., the task of representing the moralist defense: Ray’s Foreword ends with the admonition that Humbert’s tale “warns of dangerous trends” and that the book’s “ethical impact” trumps its “literary worth.” Coming as they do from the myopic Ray, these assurances are doubtful, best viewed with suspicion. To defend Lolita by invoking the didactic function and ethical purpose of literature is to commit the same Cossack mistake in the opposite direction. Art isn’t a service industry for the glorification of conventional wisdom or received ideas: art is an aggravation, an explosive device strapped to the I-beams of culture, a cattle-prod for our existential complacency. In its content, art can be transgressive, revolutionary, but perhaps the greater insurrection resides within the very precondition of art: namely, that it exists for the sake of artistry, that it defines itself according to this cultural non-value, beyond the dictates of the marketplace or the agendas of advertisers and propagandists. The pursuit of artistry, the experimentation and innovation housed within the word novel, is by definition a subversion of the social contract, a forged-in-steel, plated-in-gold fuck-you to the notion of utilitarian enterprise. (Some writers are able to convert this posture, paradoxically, impossibly, into a decent living.)

As I see it, the real subject of Lolita, its proper theme, is not immorality, but immortality. And perhaps this in itself is an affront to Cossacks, who would insist that the writer prosecute their own outrage at the crime, rather than see it subsumed within something so precious and grand as temporality. But Humbert’s pursuit of nymphets, his longing to reside on that “intangible island of entranced time,” appears to be a crazed instantiation of a larger existential crisis. Repeatedly throughout the book, Humbert inserts parentheses into his text in which he addresses the supporting cast: to a doctor who treats Lolita, “(hi, Ilse, you were a dear, uninquisitive soul and you touched my dove very gently)”; to Rita, the women with whom H takes up after Lolita escapes, “(hi, Rita—wherever you are, drunk or hungoverish, hi!)”; and most tellingly, to Jean Farlow, who shares a tender moment with the newly bereaved Humbert in Ramsdale, then dies shortly after of cancer, “(Jean, whatever, wherever you are, in minus time-space or plus soul-time, forgive me all this, parenthesis included).” All of these apostrophes are redolent of the tomb, given that we know from Ray’s Foreword that Humbert, like Lolita, has died prior to the book’s publication. Those chummy and penitent salutations emanate as if from beyond the grave, and Nabokov wants us to feel the fact, to make the spectral dimension palpable (the word for this is haunting).

The novel’s pervasive concern with temporality is captured most succinctly in Humbert’s description of his metaphysics, which is part and parcel of the novel’s artistry: he cites his academic paper “Mimir and Memory” (Humbert the scholar), in which he posits a “theory of perceptual time” that resembles the human circulatory system and bridges the poles of the past and the future (call it a fluid and equivocal time-space continuum). This circulatory system analogy applies equally to the method of the book, its imagistic reflux in which motifs proliferate madly. For one minor example, little remarked upon, consider Humbert’s arrival at the Haze house in Ramsdale, where he meets Lolita for the first time. As he prepares to tour the house, a potential lodger, he spots, in the foyer, “an old gray tennis ball” of dubious provenance. Lolita doesn’t take up tennis, as far as we know, until after she takes up with (or is taken up by) Humbert, so how do we account for the presence of the ball in the foyer? It’s as if Humbert’s memory is inscribing the earlier scene with the later event—or vice versa: perhaps the entire tennis sequence, a highlight of Humbert and Lo’s travels (precipitating a rendezvous with Quilty, among other things), is itself a spontaneous invention, a metastasis of this incongruous detail that Humbert notices in Ramsdale. (Think Kevin Spacey in The Usual Suspects, the devil who invents his far-out tale from the details close at hand—yes, Nabokov deserves a credit for this gambit too). This artistic method makes it almost impossible to separate the fact from the fantasy in Humbert’s confession—which crucially undercuts any moral takeaway obviously. Further, the interweaving of temporal layers, this mixing of times or tenses, is itself a confounding of linear narrative (in life or literature), a means of forging a realm immune to the passage of time, an art synonymous with eternity and immortality. (Morn captures the sentiment with the excellent phrase “large books that smell of time.”)

In a 1989 article, a seventeen-page conniption of sorts, Trevor McNeely argues that every attempt to take an aesthetic view of the novel is an evasion, a “basically nihilistic position of ignoring, and therefore condoning, pedophilia.” For McNeely, the book is a grand hoax perpetrated on readers, the author a reprehensible fraud. In Cossack terms, Nabokov isn’t the pedophile; rather, the evil of the novel is that he makes readers complicit in the crime: “Lolita’s critics swallow Nabokov’s bait, and come to believe, or pretend to believe, that the pedophilia and sexual slavery it depicts actually do not matter.” The most troubling thing about McNeely’s paper is that Studies in the Novel bothered to print it; yet, even an eloquent and temporally distant Cossack is welcome to a hearing. What McNeely fails, or chooses not, to grasp is that the novel’s treatment of pedophilia is, by definition, philosophical and aesthetic, rather than practical. He makes a simple category error. Nabokov portrays the subject as filtered through the prism of art to exploit neither readers nor victims of the crime, but the aesthetic possibilities of the material. To that end, Humbert’s obsession is figured as a crisis of the artistic imagination, which loosens the boundaries between fact and fiction, unmoors time from its anchor: nymphets and their mythical island don’t exist, but Humbert deceives himself into believing that they do—and this is the recipe for tragedy.

The other tragedy, Mister Morn, helps to clarify the point. In the play, the Leninist revolution is figured in the character of Tremens, a kind of prophet of death. He articulates his ideals abstractly, in archetypal images: “But why do we/ always want to grow, to climb uphill/ from one to a thousand, when the downward path–/from one to zero—is faster and sweeter? Life/ itself is the example—it rushes headlong/ into ash, it destroys everything in its way:/ first it gnaws through the umbilical cord….” Clearly, Tremens doesn’t debate the merits of particular Five-Year-Plans or even calculated purges. The revolutionary speechmaking, the offhand executions: those are relegated to the subtext. Elsewhere, Tremens links his philosophy of death, the tenets of revolution, directly to the play’s other prominent plot thread, love: “the soul/ must fear death as a maiden fears love.” The two concepts are positioned on a continuum of sorts, the one experience (death) figured as a corollary of the other (love). Does the observation of these techniques and relationships place a reader on the side of Tremens, condoning the tragedy that follows? It’s art, stupid.

Surprisingly, though, McNeely’s preposterous argument might contain a grain of truth. He suggests that Lolita is Nabokov’s vengeance on critics of every stripe: “the Freudians, the New Critics, the Existentialists, the Structuralists, and all their bastard progeny,” any interpreter who experiences “terror of the void of unmeaning.” McNeely draws the wrong conclusion, but there might be something in the observation. Nabokov’s fiction is strangely resistant, in my experience, to traditional critical approaches, even those that the author doesn’t explicitly subvert. In the case of Lolita, New Criticism, with its emphasis on structural paradox, works reasonably well. With this interpretive apparatus, we can acknowledge and cope with the troubling fact that Humbert’s Proustian quest, his pursuit of artistic immortality, also manifests in his lechery. The former, a New Critic would say, isn’t a means of ennobling the latter; the triumph of Humbert’s art doesn’t excuse the travesty of love that he perpetrates on Lolita. Instead, Nabokov’s novel composes a charged paradox of these contradictory impulses, resulting in an interpretive stalemate: Humbert’s contest with time, his triumph over mortality, might well be bogus, both aesthetically and philosophically. (Or perhaps even a sinner is allowed to finger the keys to the kingdom of heaven.) Maybe it is wicked of Nabokov to recuse himself on this sorest point, but such silence, for New Critics, is the very language of art (Keats heard it on his urn). As Humbert frames it, claiming to quote an old poet: “The moral sense in mortals is the duty/ We have to pay on mortal sense of beauty.”

The Edifice of Artifice

What the New Critical reading suggests is that it isn’t quite possible or advisable to salvage a wholesome moral vision from Nabokov’s Lolita; every avenue ends in a cul-de-sac. Even so, the perception of the paradox seems almost beside the point, inadequate somehow to the effect of the novel. Maybe, to best appraise the vision of Lolita, we have to access the amoral provinces of Formalist poetics, because in the intricate patterning of the text, its scintillating architecture, we begin to see the novel’s clearest vindication, and perhaps the most common talking point, with good cause, among the novel’s proponents. Simply put, the prose in Lolita is a marvel, a blow-your-hair-back, stand-up-and-shout performance with few equals in the annals of world literature. Consider this passage, an evocation of the American landscape as Humbert and his ward travel aimlessly cross-country, dissimulating a road trip:

Beyond the tilled plain, beyond the toy roofs, there would come a slow suffusion of inutile loveliness, a low sun in a platinum haze with a warm, peeled-peach tinge pervading the upper edge of a two-dimensional, dove-gray cloud fusing with the distant amorous mist. There might be a line of spaced trees silhouetted against the horizon, and hot still noons above a wilderness of clover, and Claude Lorrain clouds inscribed remotely into misty azure with only their cumulus part conspicuous against the neutral swoon of the background. Or again, it might be a stern El Greco horizon, pregnant with inky rain, and a passing glimpse of some mummy-necked farmer, and all around alternating strips of quick-silverish water and harsh green corn, the whole arrangement opening like a fan, somewhere in Kansas.

Nick Mount, in a lecture on YouTube, cites this passage as an attempt to inscribe nymphet-omania into the landscape, but I offer it merely as a sample of Humbert’s prose at its most majestic.

Of the human comedy, Nabokov is an equally sharp observer, a merciless recorder of mortal folly, with a Boschian bent: when Humbert’s first wife, Valeria, announces that she’s leaving him for another man, that other man turns out to be the driver of the cab that the couple is traveling in. This cab driver, Maximovich, then chauffeurs the pair back home, where he helps Valeria to pack up her things (Humbert claims to be dying the whole while of “hate and boredom”). When Valeria and her beau have gone, Humbert describes what follows:

Clumsily playing my part, I stomped to the bathroom to check if they had taken my English toilet water; they had not, but I noticed with a spasm of fierce disgust that the former Counselor of the Tsar [Maximovich], after thoroughly easing his bladder, had not flushed the toilet. That solemn pool of alien urine with a soggy, tawny cigarette butt disintegrating in it struck me as a crowning insult, and I wildly looked around for a weapon.

Immediately after, Humbert chalks up the outrage to an excess of politeness: probably Maximovich didn’t want to call attention to the shabbiness of Humbert’s apartment, in which both flush and urination would be audible in every room. The nuance of the character portrait here bespeaks an imaginative generosity, a willingness to inhabit, humanely, even peripheral lives; ironically, this is the very point on which Humbert fails with Lolita, and we should notice too that Humbert’s psychological parsing, along with some rummaging in the kitchen, spares him a pummeling from the departed Counselor, who is made of “pig-iron.” However, the rich human portraiture would come to nothing were it not for the peerless phrasing. The seething excess of “spasm of fierce disgust,” the venomous sarcasm and off-kilter, pidgin-inflected verb in “thoroughly easing,” the collision of registers, high and low, in the two types of toilet water, in the promotion of the homely cab driver to Counselor: all of this energy crackles in that “solemn pool of alien urine,” which conveys a coarse bodily function with a rich musicality, a little stilted in context, and it’s that odd formality that ignites the description and makes it sear.

In Nabokov’s sumptuous prose, readers might overlook the liberal admixtures of the mean, the harsh, the cloacal: H contemplates a swimming pool, which he feels lodged in his “thorax,” and his “organs swam in it like excrements in the blue sea water of Nice”; Charlotte Haze’s body, after the accident, “the top of her head a porridge of bones, brains, bronze hair and blood”; his own manuscript, “This then is my story. I have reread it. It has bits of marrow sticking to it, and blood, and beautiful bright-green flies.” Humbert’s isn’t exactly a decorous, museum English. His voice often betrays something florid in its inflection, something a little overheated, steroidal, wearing too much makeup. His isn’t a tone of high sincerity or grim seriousness, much less is it identical to Nabokov’s own literary voice—see for comparison the baroque and steeled serenity of Speak, Memory! (there’s a family resemblance, but Humbert would be the dissipated, loutish cousin wearing too much toilet water at the reunion). Yet Nabokov gifts him with this line, upon his high-spirited departure from Ramsdale after Charlotte’s death, an example for which the best syntactical descriptor might be catastrophe:

And presently I was shaking hands with both of them in the street, the sloping street, and everything was whirling and flying before the approaching white deluge, and a truck with a mattress from Philadelphia was confidently rolling down to an empty house, and dust was running and writhing over the exact slab of stone where Charlotte, when they lifted the laprobe for me, had been revealed, curled up, her eyes intact, their black lashes still wet, matted, like yours, Lolita.

What’s more, Humbert proves to be a skilled ventriloquist; he masterfully conveys Lolita’s tough-teen idiom (“Doublecrosser!”), as well as her mother’s bullying affection, and his own narration veers from a no-nonsense gruffness to the genuinely moving timbre of his contrition. Humbert’s tale is a monologue, but the effect is symphonic, the orchestra including both pipe organ and kazoo, yet the larger point here is simply this: virtuosic prose shimmers on EVERY PAGE of the novel. To find its equal, we have to look to giants like Joyce and Shakespeare. The prose, the artistry, the antimatter of style: this is why good and wise people revere Lolita.

Of course, it might not be wholly possible to separate the work’s style from its content. Because surely the masterful plotting of Lolita—as much a matter of matter as style—the suspenseful, carefully staged exposition of Humbert’s predatory pursuit, the untimely death of Charlotte Haze, the montages of the road trips (deliberately punctuated with pungent set pieces), the elaborate decryption of Quilty’s identity and the culminating murder: surely this contributes to the work’s triumph. Cossacks will start harrumphing again, suggesting that Nabokov might have found something a little too inspiring in the sordid content of the book. Perhaps the book’s scandalous content did in fact galvanize his imagination, did induce him to write a novel more readable, more accessible than ever before. None of his books before or after is so companionably plotted, fluidly paced, as it arcs toward its radiant zenith, despite the subtle sleight-of-hand that everywhere sabotages the chronology. Perhaps the deranged subject matter allowed Nabokov a special dispensation: he could revel more freely not in the heinous crime, but in the threadbare conventions of page-turner fiction (which he tugs at cheerfully). Who knows? Maybe Nabokov sensed that, given the book’s inflammatory subject, the writing had to be perfect. Indeed, the novel is as richly reticulated as a Shakespearean drama, as mad with reference and as ripe with metaphysics as Ulysses, as lyrical and rhapsodic and fluent in the vernacular as Gatsby (but more grotesque, wiser and deeper), as eloquent as anything in Conrad, as polished and timeless as Petrarchan marble. Yet unlike its luminous predecessors, Lolita remains uniquely, scandalously, readable, singularly hospitable to modern sensibilities. While the great works of the past often petrify over time, Lolita lives on, its colors as bright and bruising today as when they were first painted.

There is one simple and, I think, inarguable proof that, in the final reckoning, style, artistry alone has secured for Lolita its place in the pantheon of world literature. This vindication is in some ways an accident of history: to understand how, we have to consider the strange tale of the novel’s genesis, its slouching march toward Bethlehem. However, to alleviate reader fatigue, it seems wise to adjourn here for a brief rest. In the intermission, I invite you to contemplate the following rejected titles for the present article:

The Book in the Brown Paper Wrapper: Why It’s OK to Love Lolita

Nabokov’s Blues: The Tribulations of Lolita

Lolita’s Vampire Problem

The Four-Minute Medium: Why Long Essays Die on the Web

The Hard Lessons of Lolita

Bonfire of the Straw Men!

The Importance of Italics: Why We Love Lolita.

Lolita’s Genesis

In his Afterword to the novel, Nabokov attempts to answer the elementary question that many readers might ask, but that only Cossacks would charge with a special innuendo: what drove him to write such a work in the first place? Nabokov’s answer is typically oblique, but at root, this is a question of the book’s genealogy, that confluence of determinants that sparked the writing of the novel. In his introduction to The Annotated Lolita, Alfred Appel, Jr., sketches the novel’s fitful evolution, but a convenient summary of Lolita’s inception is also available online, in an article by Neil Cornwell. Cornwell tracks the first appearance of the pedophilia motif in Nabokov’s short stories and shows how a minor character in Nabokov’s The Gift pitches the very premise of Lolita as an idea for a book. Cornwell proceeds to cite a number of scholars who have tallied the novel’s literary precursors, including Edith Wharton’s The Children (which features a Humbertian romance) and Henry James’ What Maisie Knew, which concludes with “the barely teenage eponymous heroine propos[ing] co-habitation with her stepfather.” Dostoevsky’s name also crops up at times among the literary forerunners of Lolita; his The Possessed contained a chapter, initially censored, in which the hero confesses to having abused a child. Even more pointedly, Cornwell examines the fishy allegation that Nabokov cribbed the idea for his book from the little-known German writer Heinz von Lichberg, whose short story entitled “Lolita” appeared in 1919. In this case, Nabokov wouldn’t be a pedophile, but a master thief (at best) or a plagiarist (at worst).

In his YouTube lecture, Nick Mount cites the literary forerunners noted by Humbert himself: Dante, Petrarch and, most pertinently, Poe, all of whom suffered from nympholepsy. Other scholars have pointed out that those poetic ancients, Dante and Petrarch, are miscast as perverts, given that the writers were themselves children when they were smitten; similarly, scholars have speculated that Poe’s relationship with his teenaged cousin might have been chaste. While Humbert’s inventory of “classic” pedophiles might be suspect on its face, it might also contain at least one notable omission. Humbert never mentions Alexander Pushkin, sometimes called the Russian Shakespeare, who also fell in love with (and was doomed by) a young-ish girl, their romance flirting with impropriety as it straddles awkwardly the current age of consent. After writing Lolita, Nabokov would go on to translate, epically, Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, and the poet’s cradle-grazing romance receives a mention in the great story “‘That in Aleppo Once….’”: the narrator says of his own wife, “She was much younger than I—not as much younger as was Nathalie of the lovely bare shoulders and long earrings in relation to swarthy Pushkin; but still there was a sufficient margin for that kind of retrospective romanticism which finds pleasure in imitating the destiny of a unique genius.” To this list, as well, Cornwell adds, on one extreme, Lewis Carrol (whom Nabokov had also translated) and, on the other, the Marquis de Sade. The evidence here is a little erratic, but a clear trend appears to emerge. It’s hard not to think that Nabokov recognized something absurd in the prevalence of this motif (or disease)—as if literary history were a Henry Darger watercolor teeming with daisy chains of eroticized children. In this merging of the ludicrous and the tragic, maybe he found something hospitable to his artistic sensibility.

Cornwell points to another possible precursor of Lolita: he itemizes the numerous precise relationships between Joyce’s Ulysses and Nabokov’s novel, including Leopold Bloom’s unusual interest in his fifteen-year-old daughter’s budding sexuality, as well as the masturbatory encounter with teenaged Gerty McDowell (whose lameness is passed on to Lolita’s Ginny McCoo with her “lagging leg”). Suffice it to say, the novel is an overgrown garden, a Daedalian labyrinth of forking references. In fact, given the likelihood of Joyce’s haunting of the novel, this relationship might shed light on the origins of one of Lolita’s only explicit scenes (John Ray calls them “aphrodisiac”): the infamous sofa scene, the setting of Humbert’s first gratification of his criminal desire in Ramsdale.

Readers will recall how Humbert cagily manipulates the girl to facilitate his orgasm, claiming at the same time to have preserved her innocence: she doesn’t notice a thing, Humbert says (yet when the phone disrupts the proceedings and Lo goes to answer it, she stands with “cheeks aflame, hair awry”: the details of Humbert’s narrative betray him). To that end, to keep the girl distracted, Humbert, in the course of his magician’s “patter,” strikes upon “something nicely mechanical”: “I recited, garbling them slightly, the words of a foolish song that was then popular—O my Carmen, my little Carmen, something, something, those something nights, and the stars, and the cars, and the bars, and the barmen; I kept repeating this automatic stuff and holding her under its special spell,” he writes. This incantatory device, the repetitious language that undergirds the scene, might point to another Joycean precursor: consider that in “An Encounter,” from Dubliners, Joyce also chronicles a run-in with a child molester, a shabbily dressed man, well-read and yellow-toothed, who has designs on the story’s child narrator. As the characters converse on the green, the talk turns erotic and, as in Humbert’s case, incantatory: “He gave me the impression that he was repeating something which he had learned by heart or that, magnetised by some words of his own speech, his mind was slowly circling round and round in the same orbit. [….] He repeated his phrases over and over again, varying them and surrounding them with his monotonous voice.” Although wildly different in tenor, and although Joyce himself spares his boy narrator Lolita’s victimization, the similarity in the characters’ vocal performances is striking.

While allusiveness alone is hardly exculpatory, it does strongly suggest that there is much more contributing to Lolita’s creation than a simple autobiographical impulse. Cossacks, naturally, might balk at this line of reasoning; they might argue that textual genealogy is just another, highbrow attempt to naturalize pedophilia, to make it seem the norm—something analogous to Humbert’s overt pleas in the book. Yet here again, Nabokov’s lacerating irony seems to me unimpeachable: he takes the ominous tenor of Joyce’s story, for example, and turns it into mad farce. The sofa scene is ludicrous in mood and effect: “I kept repeating,” Humbert writes, “chance words after her—barmen, alarmin’, my charmin’, my carmen, ahmen, ahahamen….” No, Humbert is ridiculous in his role of enchanted hunter; Nabokov simply grants him the privilege of hanging himself with his own pen.

Beyond the artificial provinces of literature, the real world also supplied the writer with no shortage of material. First, there is the actual crime of Frank Lasalle, mentioned by Humbert in Lolita, and tracked down by scholars; in 1948, Lasalle abducted thirteen-year-old Sally Horner and traveled with her cross-country for over a year, just as Humbert does with his captive. Then, there is the case of Professor Henry Lanz, Nabokov’s colleague during his brief stint at Stanford in 1941 and possible model for both Gaston Godin, the chess-playing pederast in Beardsley, and maybe Humbert himself; in the words of Leland de la Durantaye, Lanz “married his wife in London when she was fourteen” and “allegedly revealed to Nabokov the wild array of his pedophile adventures.” In the same vein, Cornwell notes Nabokov’s close reading of Havelock Ellis’ famous case history, “The Confession of Victor X,” whose Russian narrator “develops from precociously over-sexed adolescent debauchery […,] through a lengthy period of abstinence in Italy, which finally degenerates into paedophilia, voyeurism and masturbatory obsession amid Neapolitan child prostitution.” Cornwell even cites Nabokov’s reaction to the confession, in a letter to Edmund Wilson, who had introduced him to Ellis’ work:

I enjoyed the Russian’s love-life hugely. It is wonderfully funny. As a boy, he seems to have been quite extraordinarily lucky in coming across girls with unusually rapid and rich reactions. The end is rather bathetic.

Determined skeptics, of course, may still accuse Nabokov of dissimulation, but this response is, obviously, a far cry from the commiseration of a fellow sufferer. In a larger sense, it’s clear that the precipitants of Lolita were, well, legion.

While Cornwell considers multi-media influences on Nabokov’s art, he doesn’t mention Fritz Lang’s M (1931), a classic work of German Expressionist cinema. The film, also available (amazingly) on YouTube, centers on the crimes of a child murderer (played by Peter Lorre), and it ends with Lorre tracked down by vigilantes who quickly rig up a kangaroo court to try the criminal on the spot. The scene is breathtaking in its emotional intensity, marked by monstrous shifts in tone: Lorre will be shrieking his defense, pleading for his life (as Humbert does), only to be interrupted by the devastating civility of his self-appointed attorney. The crowd of “jurors” will veer rapidly from murderous clamoring to sit-com laughter. The movie, most tellingly, ends with a bereaved mother staring balefully into space, imploring the audience to be more attentive guardians of their children. This is the same plea with which John Ray, Jr., ends his fictional Foreword: “Lolita should make all of us—parents, social workers, educators—apply ourselves with still greater vigilance and vision to the task of bringing up a better generation in a safer world.” (Note how Ray’s words seem subtly critical of Lolita as the representative of her generation.) M would be worth mentioning here, if only because it offers a succinct glimpse of the emotional extremes that typify Nabokov’s work from the same period. But the movie is equally interesting, in its content and conclusion, as another potential precursor of Lolita.

Lang’s M also takes us back, conveniently and necessarily, to the Berlin of the ‘30s, where Nabokov lived until 1937, when the Nazis hurried him out of the country. Before he left for America, Nabokov resided for a brief period in Paris (until the Nazis, again, came calling), and it was there that he experienced “the first little throb,” as he calls it, of the work that would become Lolita. The resultant manuscript, a story of 50-some pages, was called The Enchanter (published posthumously, as a book, in 1986). Written in Russian and set in France, the story contains the central premise of the later Lolita, a pedophile’s pursuit and capture of his twelve-year-old victim, by means of his doomed marriage with her mother. It remains more or less exactly faithful to the plot and method of Lolita, through the hotel scene (Lolita’s Enchanted Hunters) in which the characters’ bed down together for the first time. At this point, The Enchanter abruptly concludes, while Lolita plunges on, across the country, settling in Beardsley, taking flight again, and culminating in the chase and murder of Quilty. In his Afterword to the text, Dmitri Nabokov, the writer’s son and translator, claims that the early story is a distinct work, an independent creation, but I can’t see it as anything but a first, failed draft of the iconic novel. One detail might suffice to show just how closely the two books are related; a flower show interferes with the hotel accommodations of both Humbert Humbert and the unnamed agonist of The Enchanter.

This story, The Enchanter, as it happens, is the indisputable proof that Lolita’s rightful fame has nothing to do with titillation, that readers and fans of Nabokov’s fiction are not condoning, much less celebrating Humbert’s crime. And here’s why: although The Enchanter takes up the same demented content as Lolita, almost no one reads it, and no one, to my knowledge, reveres it. In “The Enchanter and the Beauties of Sleeping,” Susan Elizabeth Sweeney gives the text perhaps more attention than it warrants, tracking the fairy-tale motifs that Nabokov exploits (the Red Riding Hood references are impossible to miss). But my impression is that very few readers even know that The Enchanter exists—this, despite Stephen Smith’s dutiful documentary, and despite the fact that Lolita’s Wikipedia page contains in its fine print a reference to the work (watch for its Russian-language title Volshebnik—which looks strangely like an anagram for Bolshevik, to boot). Apropos of the plagiarism scandal, Cornwell and others have noted how difficult it is to prove a negative, an absence of knowledge, so all I can offer by way of evidence for The Enchanter’s obscurity is this: that New Yorker-interviewed pedophile doesn’t include the title of The Enchanter among his secret stash. If Cossacks were right, if Nabokov’s fans were criminals, The Enchanter would also be a household name. It isn’t (though Lila Zanganeh’s book title, The Enchanter: Nabokov and Happiness, seems increasingly audacious.).

Nor should it be. In one of fate’s many ironies, this book, which incontrovertibly exonerates readers, at the same time makes it hardest to vindicate the writer. The plot, per the text’s length, is paper-thin, its course excruciatingly linear, its focus painfully myopic and claustrophobic, everything about it wooden and under-aired. For all its traumatic content, it might be a little boring. Nabokov’s brilliance does at times rouse itself long enough to cast a bleary eye on the proceedings, before lapsing again into dormancy. For example, as the agonist contemplates the act of consummating his sham marriage to his Brobdingnagian bride, we’re privy to the black comedy of her anatomy: “it was perfectly clear that he (little Gulliver) would be physically unable to tackle those broad bones, those multiple caverns, the bulky velvet, the formless anklebones, the repulsively listing conformation of her ponderous pelvis, not to mention the rancid emanations of her wilted skin and the as yet undisclosed miracles of surgery… here his imagination was left hanging on barbed wire.” But Erica Jong offers a capsule summary of the relation between the story and the novel: “The difference between [the texts] is the difference between a postcard from Venice and a Turner painting of the same scene.”

The Enchanter is interesting primarily for what it isn’t. It contains in utero some of the basic material and tactics that make Lolita incomparable: a passing reference to Hourglass Lake, where Humbert considers murdering Charlotte (“some seaside sand useful only as food for an hourglass”); an ur-Quilty in The Enchanter’s hotel; a prefatory attempt by the agonist to rationalize and philosophize, like Humbert, his obsession. Importantly, the story also prefigures Lolita’s tactic of lampooning and, in a moral sense, condemning the agonist’s schemes. After the untimely death of his ailing wife (in hospital, a nicety that also survives as a ruse in Lolita), the man takes a train to collect his stepdaughter; while in transit, he fantasizes about the night to come, his gradual assault on the girl’s virginity in the “tightest and pinkest sense,” and the text incorporates and confirms the reader’s response in the character of a woman who shares the train compartment: “The lady who had been sitting across from him for some reason suddenly got up and went into another compartment.” The silence of that “for some reason” speaks volumes: even through the blinders of third-person-limited narration, the text manages to convey that the agonist has visibly aroused himself, and caused the woman to bolt.

But perhaps what The Enchanter lacks, even more than Humbert’s comic self-laceration, even more than the novel’s three-dimensional world, is a greater allotment of this authorial intervention. The story’s conclusion is especially difficult to read, as Nabokov appears to ride the current of the narrative beyond the boundaries of good taste. The agonist finds himself, at last, in the hotel room with his prey; believing the girl to be asleep, he begins to weave his spell over her body, availing himself of his “magic wand” (thus, the title), which appears to be a euphemism for his penis. Yes, it’s almost too silly even to be creepy. Belatedly, the character recognizes that the girl has in fact been awake for a while and is screaming at the top of her lungs. The story rushes to its end, then, with the agonist fleeing the scene, seeking a convenient suicide, only to be struck down in the street by an obliging truck. Strangely, at this moment, the style veers directly into stream-of-consciousness narration, as the agonist welcomes his violent end (for my part, I prefer the third-person-indirect phrase that precedes this turn, “this instantaneous cinema of dismemberment”).

Nabokov must have recognized the failure in the sequence—else, he would never have rewritten it as he did. Humbert, in The Enchanted Hunters hotel, passes the whole night suffering from insomnia and dyspepsia, and the morning tryst is a masterpiece of understatement: “by six-fifteen, we were technically lovers.” Yet, something of the edge, the creepiness, of The Enchanter survives in Lolita, in the very hotel scene which features one sentence that will challenge the stomach of any reader. It describes Humbert’s anticipatory image of the girl, and depicts her anatomy starkly, unflinchingly:

Naked, except for one sock and her charm bracelet, spread-eagled on the bed where my philter had felled her—so I foreglimpsed her; a velvet hair ribbon was still clutched in her hand; her honey-brown body, with the white negative image of a rudimentary swimsuit patterned against her tan, presented to me its pale breastbuds; in the rosy lamplight, a little pubic floss glistened on its plump hillock.

There have been times when I have asked myself what the novel would lose if one were simply to strike this sentence from the page. Basically, in such moments, I have contemplated censorship of a kind. Why would Nabokov write such a sentence in the first place? Or similarly, why dramatize with such heat and precision the sexual escapades of Humbert and Annabel, when both were Lolita’s age? Humbert writes of Annabel, “whenever in her solitary ecstasy she was led to kiss me, her head would bend with a sleepy, soft, drooping movement that was almost woeful,” and the lyricism of the line rings so true that the sentence strikes with the force of memory. At such moments, it almost becomes possible to sympathize, somewhat, with the Cossack position. But before we leap into that intellectual abyss, we have to realize that in this, in many things, Nabokov was smarter, wiser, braver, than any of us. Without such passages, I’ve concluded, it might be possible to read the novel without feeling sufficiently repulsed.

Such moments bring to the surface the horror that bubbles steadily in the margins of Humbert’s tale; it skitters across the frame of the page, never far from view, seeping in from the edges, muted and ghastly in its attenuation. In the wake of the events at The Enchanted Hunters, for example, Humbert pauses to describe the mural that he might have painted for the hotel, had the proprieters “lost [their] minds”:

There would have been a sultan, his face expressing great agony (belied, as it were, by his molding caress), helping a callipygean slave child to climb a column of onyx. There would have been those luminous globules of gonadal glow that travel up the opalescent sides of juke boxes. There would have been camp activities…. There would have been poplars, apples, a suburban Sunday. There would have been a fire opal dissolving within a ripple-ringed pool, a last throb, a last dab of color, stinging red, smarting pink, a sigh, a wincing child.

The mural supplies a loose corollary, a hieratic version of Humbert’s confession. And if you can read that “wincing child” and not feel lanced by grief, you should either have your conscience checked or learn to become a better reader. The method is oblique, but the result is a wound.

My sense is that, if Nabokov had written only The Enchanter, the Cossacks might have a better case against him. But then again, if Nabokov had never gone on to write Lolita, there wouldn’t be any museums to vandalize. And because Nabokov did write Lolita, we can’t indict him for the limitations and failings of an early draft whose publication he considered (in 1959), but never approved. To put this simply, the evidence of The Enchanter serves to exonerate both the author and his readers. It’s doubtful that an actual pedophile would be capable of artistic (rather than pornographic) revision; it’s certain that readers would be indifferent to anything but an artistic triumph.

Lolita’s achievement is of such an order that it precipitates and compels every kind of artistic response, from imitation to inspiration to competition to homage to a desperate lunging at the maestro’s coattails. See again Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, his magnum opus, with its ship of lost souls whose bacchanals might make Sade blush; the shipboard set piece concludes with a pedophiliac tryst considerably more erotic than anything in Lolita. (If memory serves, this scene ends with the male participant, the book’s protagonist, Rocket Man, passing through the wormhole of his own urethra.) Yet Cossacks will likely excuse Pynchon from their auto-da-fé, partly because such depravities are walled off behind a fortress of impenetrable prose, and they will leave alone, thankfully, Gary Shteyngart with his wave to Lolita in one of the best American stories of the new century, “Shylock on the Neva”; Shteyngart’s gangster narrator spies a young girl at a museum and flashes his “standard Will-you-sell-your-body-for-Deutschemarks? smile. […] Not yet, her black eyes [tell him].” Nor will the Cossacks touch their torches to the digital record of the Oscar-lauded American Beauty (another Kevin Spacey sighting) with its unsubtle, rose-encrusted reprise of Nabokov’s novel. Lolita even intrudes on the latest book by the turncoat Martin Amis, Lionel Asbo; the novel begins with the fifteen-year-old male protagonist prosecuting an incestuous relationship with his Humbert-aged grandmother. No, perhaps the only unforgivable thing about Lolita, the thing that makes it uniquely susceptible to attack, is that Nabokov managed to turn a tragedy into a trope.

Cossacks might try, but surely not every instance of literary child abuse can be traced back to Nabokov; only among writers of a certain stylistic cast is the ancestry clear (they write prose that bioluminesces and stings like a Portuguese man’o’war). In any case, contrary to Cossack opinion, the proliferation of Lolita’s flammable premise is neither trivializing nor sinister. Rather, in evoking Nabokov’s achievement, writers not only honor the best of the tradition, they consent to shoulder in their own ways the novel’s grim burden: to confront the very worst that humanity has to offer, and to wring from that misery something beautiful: to stare into the blackest pit and find (forge) the sun. This is the hard lesson of Lolita; it is a monument to an awful existential truth: simply to be alive, in the face of the whole history of human suffering, requires a kind of insane fortitude. Lolita reminds us that while soldiers were dying in European trenches, Monet was painting lilies in his garden; that horror and beauty are cosynchronous; that for every fine sentiment, every sweet emotion, someone else pays in blood, and eventually we all get presented with the check. The world is thick with atrocity, past and present; Lolita shows us that, from such material, within and out of it, we might wrest some measure of transcendence. The novel casts its gaze on the monstrous, but also the mythical, the banal, the comic, the poetic, even the tender (with an asterisk), and fashions a kind of harmony from the discordant and myriad particulars. A sob of despair becomes a song of hallelujah. Though perhaps beyond morality in the narrow sense, the novel’s project, this artistic patrimony, is at its root affirmative and redemptive.

The Cossack storm—a light shower, really—will soon blow over, if it hasn’t already. The circus can always be relied upon to leave town. Although it would be wrong to compare too closely the offenses of Cossacks with those of actual pedophiles, they do have this in common: both, in the end, are acts of sterility, the one perhaps trivial, the other savage. Nabokov’s novel, on the contrary, and fit testimony to its genius, is blessedly, maybe endlessly, generative.

— Bruce Stone

.

Bruce Stone is a Wisconsin native and graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts (MFA, 2002). In 2004, he served as the contributing editor for a collection of essays on Douglas Glover’s fiction, The Art of Desire (Oberon Press). His essays have appeared in Miranda, Nabokov Studies, Review of Contemporary Fiction, Numéro Cinq and Salon. His fiction has appeared most recently in Straylight and Numéro Cinq. He’s currently teaching writing at UCLA.

.

.

From the Stanley Kubrick film Lolita.

From the Stanley Kubrick film Lolita.