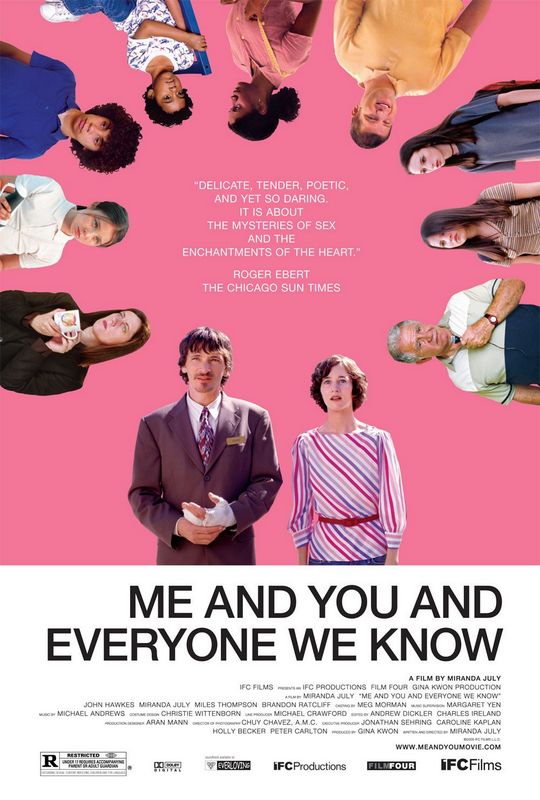

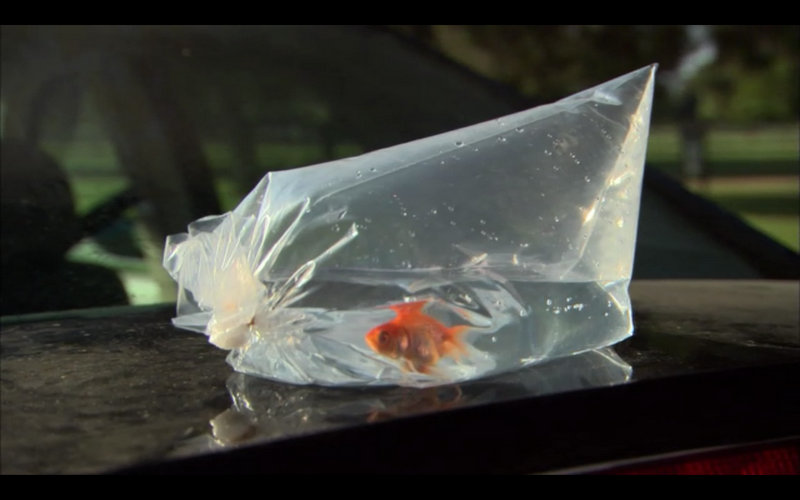

Occasionally, in the structure of a larger film there will appear a scene or sequence that can stand on its own, discretely, as its own short film. Here I would include the opening scene to Neil LaBute’s Your Friends & Neighbors, the seduction / meeting scene in Julio Medem’s Sex and Lucia, the “Hotel Chevalier” short shot alongside Wes Anderson’s The Darjeeling Limited (a separate film but theatres often screened it with the feature and it contains events referred to throughout the film), and this short set of scenes spanning the story of a goldfish on a freeway in the middle of Miranda July’s first feature film Me and You and Everyone We Know.

Structurally each of these shorts can be viewed discretely from their feature films and some, as in the case of July’s goldfish story, may even seem like an aside, though I think it still adds something tangentially to the larger film it belongs in. Some like “Hotel Chevalier” are subplots. Others like the opening to Your Friends & Neighbors and Medem’s seduction scene are building blocks of the main plot but could still exist as separate entities. Despite these differences, what they do have in common is that they provide enough narrative cohesion and catharsis to exist on their own if they had to. Or if you wanted to see them that way.

The goldfish sequence is tonally and stylistically similar to the rest of the film it appears in but is also similar to “Are You the Favourite Person of Anybody?” which was previously featured in Numero Cinq at the Movies. In July’s worlds we find absurdist realities where what happens is probable, realistic, but told in an overdrawn way, here particularly evident in the dialogue between Christine (Miranda July) and Michael (Hector Elias).

There are also strong similarities between this oversaturated reality and the style of Jane Campion’s short films (which were also featured in Numero Cinq at the Movies) which is no surprise as July commonly cites Campion as one of her inspirations and influences.

Though the goldfish short fits within the feature it is a part of, viewed on its own it offers a different experience. It is then a short film about loss, about condensed meaningful moments, and connection between strangers witnessing those moments. This isn’t at odds with the feature film it belongs to, but is in hues and tenor more melancholy than the rest of the film.

There are two things which tonally shift this shared sad experience, though, and keep it from plummeting into melodrama: 1) the couple in the vehicle that is the goldfish’s penultimate landing place are oblivious to the goldfish’s last moments, even though, as Michael notes, “at least we are all together in this.”

2) It’s about the death of a goldfish, possible the world’s most disposable pet. Truly, for the goldfish, these last moments hurtling down the freeway in his little bag of water might be a much more euphoric way to die than the neglect and probable toilet bowl funeral ending that would have awaited him at the little girl’s home. Regardless, the accidental death that connects these strangers is light on tragedy as a result.

All told this mixes into something sublime: a little accident, a little collision between strangers, a little loss, all finding something meaningful and significant that is more than a little beyond words.

None of this is intended to disparage the larger work, July’s absurd and lovely first feature Me and You and Everyone We Know. It’s just there’s a pleasure within the pleasure. And this might be worth tasting on its own.

–R. W. Gray