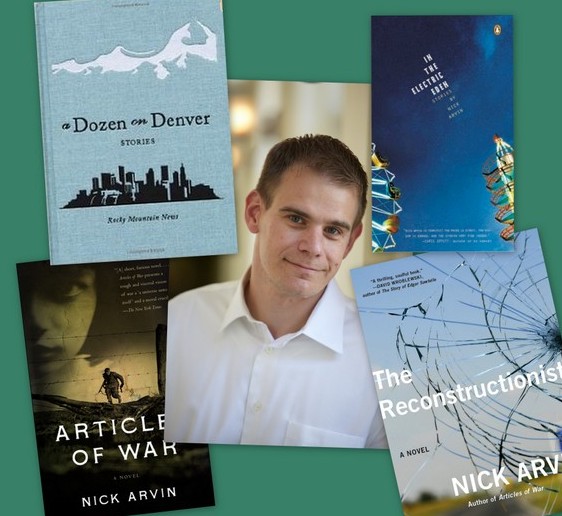

Nick Arvin is a writer and an engineer. The characters in his stories are befuddled by the mechanics of a technologically complicated world. Whether this technology is as novel as the first can opener or as complexly dangerous as a Ford Fairlane (sans airbags), Arvin’s stories frame such technology, including the alternating current Edison once used to electrocute an elephant (see video below), from the perspectives of characters who can’t even imagine how these gadgets and gizmos will simplify their lives and simultaneously pull their lives apart.

Arvin’s emphasis on the disillusion of technology subverts the expectations of both his characters and his readers. In the title story to his short story collection, In the Electric Eden, the narrator recounts his grandfather’s story of witnessing Topsy the Elephant stampede his uncle at Coney Island. Later, the grandfather describes how he still felt guilty for condemning the elephant to a death that was as much about Edison’s war with Tesla as it was a blatant display of technological might.

In The Reconstructionist, Arvin’s most recent novel, his main character Ellis Barstow recreates the car accident of his brother’s death by crashing in the same dangerous intersection. Even though the re-staged crash almost kills Ellis, the experience irrevocably alters his understanding of the impermanence of his own life. Arvin’s first novel Articles of War, which was inspired by the World War II execution of Pvt. Eddie Slovik for cowardice, tells the story of an eighteen year old soldier (nicknamed “Heck”) who struggles with the mechanics of war—both as a cog on the front lines of the war machine and as a kid barely in control of his own cowardice and fear.

(Author photo credit: Jennifer Richard)

— Jacqueline Kharouf

§

Jacqueline Kharouf: In an interview you gave for your engineering company newsletter (the interview was posted on your blog), you explained that your most recent novel, The Reconstructionist, took you six years to write, that your first novel, Articles of War, took three years, and that you will sometimes spend years perfecting a short story. Can you describe your drafting and revision process?

Nick Arvin: I’ve never been able to start a piece at the beginning and just write it through. I’ll have some vague idea and I’ll start writing fragments around the idea to try to get into it somehow. I try to come up with characters and situations. I write these little pieces—sometimes it’s just a line or two and sometimes I go on for pages—and explore the idea, and try to figure out a story around it. And I’ll keep doing that—just throwing down these little fragments—until they start to add up and I start to have a pretty clear picture in my mind of what the story is, or at least a good section of the story.

Then I get out the computer and I type in the fragments that fit in the story that I have in mind. These fragments aren’t necessarily connected very well, so then I spend a lot of time trying to work out transitions. I tend to do more creative process stuff by hand, so I’ll go back to writing by hand when I’m trying to figure out new material. Once I have a complete story, I’ll print that out and mark that up by hand. Maybe I’ll realize I need new material or there’s a scene that’s not working and I’ll rewrite it again. I’ll do that in the notebook and then go back and put it in the computer. I’ll show it to some friends and get some feedback and that’ll crystalize some new ideas. I’ll go through that process again and again. With most stories, I go through about 10 drafts on average.

JK: With that drafting and revision process, does your process change when you’re starting a novel or starting a shorter piece? How do you identify if it’s going to be a novel or if it’s just going to stay a short story?

NA: When I started writing Articles of War I was trying to write a short story, but it quickly became a novella. I was at the University of Iowa at that time, at the Writer’s Workshop. I workshopped that novella and everybody told me that it needed to be longer. Turning it into a novel, in hindsight, went relatively quickly for me because it was a matter of fleshing out what I’d written in this shorter version. I had kind of a framework to work with. So it, you know, only took three years.

With The Reconstructionist, I had all this great material from working in the field of forensic engineering and accident reconstruction. And I knew from the beginning that thematically and, in terms of just the amount of material that I had to work with, I wanted to do something that would have to be a novel. I couldn’t capture what I wanted to do in a story. But, I think it took six or seven years to write because it took such a long time to figure out a narrative framework that captured those themes and used the material that I wanted to work with in a way that hopefully enlarges it and gives it context and makes it more than just a series of anecdotes.

JK: George Saunders, who studied geophysical engineering at the Colorado School of Mines and later turned to writing, spoke to Ben Marcus in a conversation printed in the The Believer Book of Writers Talking to Writers. When Marcus asked Saunders if he differentiates between fantastic or realistic writing, Saunders explained that he doesn’t differentiate. “What I find exciting is the idea that no work of fiction will ever, ever come close to ‘documenting’ life. So then, the purpose of it must be otherwise. It’s supposed to do something to us to make it easier (or more fun, or less painful) for us to live. Then all questions of form and so on become subjugated to this higher thing. We’re not slaves any more to ideas of ‘the real’ or, for that matter, to ideas of ‘the experimental’—we’re just trying to make something happen to the reader in his or her deepest places.” Even though you and Saunders both share a background in engineering, your work seems to focus on a very specific and detailed reality. And it’s not that I’m implying all engineer-authors should write in the same way, but it seems that the worlds you write about are heavily controlled—realistic within the results of Newtonian equations, vectors, or even the conformities and expectations of soldiers at war. Do you consider your work to be fairly realistic? (And if so, is this part of your intention as a writer?) Or, do you write simply to “make something happen to the reader in his or her deepest places”?

NA: That’s a complicated question. I do consider my work realistic, for the most part. I published a story recently in a journal called Midwestern Gothic that was clearly not realistic. And, I’m actually trying to get started now on a novel that would have elements of science fiction. So I’m interested in that kind of thing. Mostly I just try to be true to the story itself. I don’t want to write a story that doesn’t come out as honest and true because I’m hung up internally on writing only realistic stuff or nonrealistic stuff. You can write fiction where everything that happens is realistic and yet still feels somehow a little outside or displaced from the real world. Kazuo Ishiguro does that in some of his novels, like The Remains of the Day. He’s writing in a realistic mode but there’s something about it that makes it feel like he’s describing a world that’s a little bit different from our world. I admire that.

I’ve been thinking about this a little bit because when Articles of War came out, there was somebody who described it as “surrealistic,” which really surprised me. I felt like that book was very much grounded in reality. But perhaps what that reader was reacting to is the way that the reality that the book is describing is so extreme and terrible and tense because of the nature of the experience of war, that it feels outside of our reality. War itself is surrealistic.

I feel like there’s something of that too in The Reconstructionist. Another interviewer asked me about my intentions, because he said that to him The Reconstructionist felt like it was not realism. I told him, “Well, to me, it’s realistic. Everything is rooted in reality.” But I think he was really asking about how The Reconstructionist is wound very tightly around certain thematic elements. For example, there’s a moment in the book where Ellis, the main character, is feeling like he’s had all these car crashes in his life, it’s overwhelming and bizarre to him. But because he’s an engineer he’s doing the math in a sort of statistical way, and he asks himself what are the odds of this happening to someone. And he realizes that only a couple accidents have actually impinged on his life, and then through his work he has chosen to bring a lot of other accidents into his life.

If you haven’t been involved in a car accident yourself, you certainly know somebody who has. These car accidents are a huge feature of American life, but we don’t talk about them very much. That was something that I wanted to bring out in the book and force people to look at it. I feel like people, in a way, would rather ignore it. Me, too, sometimes. I’m going to get out of this interview and I’m going to get in my car and drive home—I don’t really want to be forced to think very hard about the fact that it’s entirely possible I could die on the way.

And with the George Saunders quote…I like what he’s saying there. What he’s responding to is the question: what’s fiction for? When I think of that question, I tend to come back to an essay that Marilynne Robinson wrote a few years ago. The title* of it was something like: “You Don’t Need to Doubt What I’m Saying Because It Is Not True.” [Laughs] If I remember right, she was saying that this was something the Greek chorus would chant at the beginning of a play. Robinson’s idea was that one of the most important aspects of fiction is that we create a context where we can begin by telling you now: it’s all made up. A lot of times in our daily lives, we get hung up on the question: “Is this true, is that true?” If you’re reading a piece of nonfiction on some level you’re constantly trying to assess is the story that this person is telling me really true, or is it a James Frey thing? Fiction allows you to let go of all that and not worry about truth in a “did it actually happen” sense. That frees you up to deal with stuff that touches on the heart, or stuff that touches on—for lack of a better word—philosophy.

*The title of Marilynne Robinson’s essay is “You Need Not Doubt What I Say Because It Is Not True.” It was printed in A Public Space, Issue 1.

JK: In your first novel, Articles of War, which takes place in World War II, war artifacts or articles serve as metaphors for the destruction and disruption of life in times of war and often link back to the main character’s traumatic flashbacks and imagery. Is this focus—the small, often lost items of war—part of the reason for the title?

NA: It’s a funny story about that title. When I was working on the manuscript, the working title for the book was “Yours for Victory,” which is how Eddie Slovik signed off his letters. And it just seemed like such an extraordinarily tragic phrase for him, of all people, to use. When my agent was shopping the book around for me, we had a very hard time finding a buyer. It came down to this one editor who was interested, but I had to make some changes before he would commit to it. And the title was the last thing that he didn’t like. At that point I was so relieved to place the book with a publisher that I was just like fine, no problem, we’ll find a new title.

But then we spent months trying to find a title. My agent threw some ideas out, the editor threw some out, I threw some out, but nobody was able to offer anything that didn’t suck. And then, it was coming down towards the deadline and my editor threw out this title that came from Shakespeare. He was really excited about it, but I hated it. I can’t remember what it was now, but it sounded to me like a horror movie title. [Laughs] But my editor was really excited about it, he was like, “This is it.” I called my agent and I said, “I hate this title.” My agent said, “Yeah, I don’t like it either,” so he called the editor and argued with him about it. Eventually, the editor said, “Fine, but we need a title. What are we going to do?” My agent said, “Well I don’t know, we could find some documentation related to the war to look through for phrases, stuff like the Articles of War.” And the editor said, “That’s it! ‘Articles of War’!” They both called me, they were both so excited. I was excited too. It was clearly the best title we could come up with. Looking back on it now I actually think I would go back to “Yours for Victory.” However, I did like “Articles of War” because the Articles of War, as a legal document, relate to what happened to Eddie Slovik, and the place that Heck (the main character) finds himself. And I think there’s a way that war objectifies people who are involved in it, makes them into things, articles.

JK: I want to ask you about how you created both this very close and very broad perspective throughout the novel. At times, we were very close inside Heck’s head and at others you constructed this wide perspective of the war. You state it very beautifully (and succinctly) towards the end of the novel: “It was a curious thing, that in the time between the shots and the echo of the shots a man could die, that so monumental an event could occur in so trivial a passage.” How did you work to balance both this vertical perspective into the character and a horizontal scope that described the action and movement of war?

NA: When I was working on Articles of War I had a voice in mind that included some of that “vertical” and ten-thousand-foot view that gives you some perspective on things. I really admire a novella by Jim Harrison called Legends of the Fall which has those elements of perspective. I felt like it was important to give some larger context to events. If you just describe a war in terms of these small details I think you would lose some of the human feeling of it, because there’s something so inhuman about war itself. It’s almost like you need that larger voice to come in once and a while to remind yourself of the people involved, that they’re involved in this inhuman endeavor and yet they are human.

JK: And then what was your thought process for choosing when to move inside the characters and create a close, internal perspective?

NA: In that case, I think I was really trying to pull inside as much as possible in the critical moments of the action of being a soldier. One of the things I was thinking about as I started on the book was that there haven’t been very many books that do a good job of getting inside just how fucking scary it would be to be in combat. I really wanted to try and bring that out as much as possible, and give the reader that experience as much as I could. I wanted to sit in those moments where you, as a soldier, would feel yourself totally lacking control of your life and your fate, the moments when there’s a very good chance you could die at any moment and how terrifying that would be. Those were the moments I really wanted to zoom in and focus on the interior feeling.

JK: In his introduction to your reading at the Tattered Cover, David Wroblewski, the author of The Story of Edgar Sawtelle, said that your book The Reconstructionist centers on the idea that what a person does with their life changes their focus on the world. As someone who is doing two things with his life—writing and engineering—how do these things, these very different activities, change your focus on the world?

NA: That’s an interesting question. One of the things that I like about doing both of those things is that I feel like they are very different ways of looking at the world. It’s a relief sometimes to go from one to the other and have a different perspective, to use a different part of your brain to try and figure things out. There are a lot of similarities too.

Writing and engineering are both processes of taking little things and putting them together to make some sort of larger system. In writing, it’s words; for me in engineering, it’s putting pieces of steel together. If you do it well you get some larger thing that uses all those little pieces in a harmonious way and creates something that’s larger and more pleasing and more useful. Maybe it’s Moby Dick, or maybe it’s a cruise ship.

But the difference I find myself thinking about has to do with ambiguity. As an engineer you hate ambiguity. When there are questions that you don’t know the answer to, it’s your job to find the answer to those questions. If I’m designing something in a power plant and if I don’t know how something is going to respond in a certain situation, or if this pump fails what’s going to happen, I have to figure it all out because if there’s a question you forgot to ask or a question that you blew off, people can die.

As a writer, you have some of that too. As I’m working out a sentence, I don’t want there to be ambiguity about what that sentence means. I want the sentence to be clear in itself. But a lot of what you’re doing at a larger level is structuring things around ambiguity. As a writer, you will actually look for questions that don’t have answers. The process of writing is a process of framing those questions and even exaggerating them to make them dramatic. Questions like how do you know who you are, questions that have no answer. It’s pleasing for me to be able to go between those kind of modes. I like finding answers to things and engineering gives you tools for doing that, but I wouldn’t know how to live without the writing to give me a structure for exploring questions that don’t have answers.

For more on the topic of ambiguity, see Arvin’s essay, “An Engineer’s Blueprints For Writing,” which he published April 16, 2012 in the Wall Street Journal.

JK: You mentioned, at your Tattered Cover reading, that you worked as a forensic engineer (or reconstructionist) like Ellis Barstow, the main character of the novel. What is a reconstructionist?

NA: A reconstructionist is a person who looks at an accident and examines the evidence left by that accident and tries to figure out how did the accident happen, what were the causes. In my case, I worked on car crashes, so we would look at marks on the roadway left by tires, we would look at the shape of the damage to vehicles and any other physical evidence that was left by the accident. Then we would use that evidence to build a story about how this accident had occurred and to help develop answers to questions about who was at fault, because a reconstructionist typically works for either an attorney or maybe an insurance agent. We built that story using physics. Often you start at the end and work backwards from there to figure out ultimately how fast vehicles were going, whether they turned this way or that, hit their brakes, or whatever they may have done.

JK: Other than inspiring an idea for a novel, was this work fruitful to your work as a writer?

NA: That’s an interesting question too. I don’t know. I would have to think about that. I always thought the work itself was really interesting and interesting to people. I wanted to bring that out in the writing. Then the stories of the people involved in these accidents are also very interesting and tragic. So, the work handed me all this great material, but I haven’t really thought that much about how the work itself might have fed the writing process.

When I was saying before that a reconstructionist creates a story, that’s not language that most reconstructionists would use. They wouldn’t call it a story; they would call it a re-creation, or something. But, as a writer, I found myself very aware that what we were doing was creating stories. We were creating a little narrative based on the evidence and so there was a kind of overlap between what I was doing as a writer and what I was doing as a reconstructionist.

I’m moving on to other stuff—I’m not writing about car crashes any more—but I’ve found that since I’ve finished The Reconstructionist I occasionally do find myself thinking about that process of reconstruction. It may be in part because of the process that I use, that I was telling you about, having all these little fragments that I piece together. There’s something like reconstruction there, where you’ve got little pieces of evidence, and you’re trying to create a story around them.

JK: As I was reading the novel, I wondered if this “reconstruction” was part of your process for teaching yourself the story. The characters crash together—both in cars and in life—and I wondered if you began with the moment of that “crash” or “accident” and then worked your way backwards to reconstruct what brought the characters to that cataclysmic moment.

NA: Again, because I work in these sort of fragments that I then have to piece together, I often begin by putting my characters in an interesting place and then the writing process is a process of trying to figure out how they got there and what it says about them as a character. It’s a process of making the character real. Articles of War actually was kind of a long version of that because I started with the execution of Eddie Slovik at the end of the book. I had this little vignette that I’d written from the perspective of a soldier who was in the firing squad. That was all it was. Then I needed to figure out what am I going to do with that, and the question was, well, how did he get into that circumstance?

JK: Your third-person point of view, which focuses on the main character Ellis, tends to slip into these analytical observations of what’s happening in the story. As the story progresses and events escalate, these analytical rants seem to become even more exaggerated, as though Ellis is unsure of his grip on what he’s doing, or supposed to be doing. Like Ellis, did you obsessively analyze the events of the story, the situations, relationships, characters, the risks and end goals, in a way to teach yourself the steps of the story as it accelerated?

NA: That’s another way that I feel like writing and engineering are similar. I mean, people think of writing as a very creative process and engineering as a very analytical process, but they both start with a creative aspect. What I do now is design work for power plants and gas facilities. You start with a blank piece of paper and you steal ideas from here and there and assemble a system hopefully that works for whatever the particular problem is. In that way, engineering is just like writing. You start with a blank piece of paper and you’ve got some idea of what you want to do, but you’re not sure, at the beginning, how to do it. You steal some ideas from other books you’ve read, get a draft down, clean it up, and then you show it to somebody. That process in writing of cleaning things up is very analytical. It’s a process of saying this part of the story doesn’t work and trying to analyze why doesn’t it work and then creating a solution and trying to plug that in. You do the same thing in engineering. It’s a process of determining why this part of my system isn’t going to work.

Ellis, for me, is a guy who’s trained himself too well in that and it’s become his only way of understanding and processing the world. It detaches him from other parts of himself. So, as the book progresses, like you said, his life is coming apart and the only way he knows how to try and understand that is to try and apply that process of analysis.

JK: The title story of your short story collection, In the Electric Eden, is set in the early part of the twentieth century. You also wrote “Armistice Day,” a short story for an anthology titled Dozens on Denver, which is also set in the early twentieth century. I wonder if you could speak to the research aspect of those historical fiction stories. Did you do a lot of research and was that part of the inspiration for these pieces?

NA: “In the Electric Eden” was the first historical story that I wrote. It started because a friend mentioned this story about Edison electrocuting an elephant as a part of Edison’s war with Tesla. Edison’s technology was direct current, and Tesla had alternating current. Edison was telling people that alternating current is dangerous, that you shouldn’t let it into your house. To prove that, he did a couple of things. First, he invented the electric chair and used alternating current in the electric chair. And second, he had this traveling road show where they would electrocute cats and dogs to show people how dangerous it was.

Then this opportunity came up where these guys on Coney Island had an elephant that had killed a guy and they saw an opportunity, with Edison, to use this new electrocution technique on the elephant. Edison filmed it so that he could include it in his roadshow. I didn’t know all that, but a friend had mentioned that he’d heard this story about Edison electrocuting an elephant. This would have been 12 years ago, but they did have Google then. [Laughs] So I got on Google and I found this mpeg online of the film that Edison had made.

[youtube]http://youtu.be/RkBU3aYsf0Q[/youtube]

It was just so stunningly strange to me that this event that was tied to the early days of electricity was now on my computer screen 100 years later, being fed by alternating current. There’s a couple layers of irony there. It was fascinating to me and I wondered if I could write a story around it, so that drove me to start researching what had happened and why the elephant had been electrocuted. It was a front page article in the New York Times, the day after the electrocution. There were great details in that article, and it was really fun to write. One of things that I liked about it is that it was kind of a relief on the creative process. When you’re just creating stuff from your own head, it’s like you’re squeezing these things out. It’s such a strain sometimes. When I was working with this story that was built out of historical details, I could pluck these details out that I knew were interesting, or little anecdotes or whatever, and find ways to work them into the story. It was just really fun. So, I went from there to doing several other stories that are historical, and then Articles of War.

JK: Do you think you’ll do a collection of historical fiction?

NA: Maybe, someday. The problem with it, for me, at this point in my life, is the historical research is pretty time consuming and I just don’t have the time right now to do the research and get writing done and read. I really need to read fiction just to feed my process. I feel lucky that I have other elements of my life that are interesting that can feed my fiction. But I’d like to get back to it someday.

JK: I also found it interesting how in both “In the Electric Eden” and “Armistice Day,” you begin the story movement with an initial and unusual visual sight and reframe that image by creating moments within moments. In both of these stories the visual imagery reveals the narrative conflict. Is this visual imagery indicative of how you begin to write about these historical moments? In other words, even though you’re describing moments beyond your personal experience, does the imagery help you understand the emotional root of the conflict?

NA: My stories often start with an image and then everything else ends up developing, flowering, around that image. Certainly, “In the Electric Eden” started with that film. That’s a moving image. I’m trying to remember the origins of “Armistice Day.” That story was written for the Rocky Mountain News, may it rest in peace. [Laughs] They had this wonderful project. They got a dozen writers who live in the Denver area to write a series of stories set in Denver. They asked each writer to set their story in a different decade. I disputed with them for a while over my contract for this thing, as a result of which everyone else had picked their decade by the time we worked out the contract issue. The 1910’s were all that was left. So I just sort of went into it with an attitude of, well, I don’t know anything about Denver in the 1910s, I’ll dig around and see what’s interesting. I was looking through old newspapers on microfilm and looking through some history books, and the thing that really struck me was an article, or maybe a couple of articles, about Armistice Day. I remember they talked about these “bombs,” they called them “bombs”—I assume that what they really mean, in our terminology, is fireworks. The news of the armistice was wired in and got into Denver in the middle of the night, so the newspapers immediately started printing special editions, and they fired off these “bombs” to let people know there was big news and everybody should come get their newspaper because there was no other way to get news. So there were these quote-unquote “bombs” going off and people pouring into downtown in the middle of the night. A huge spontaneous party erupted and they partied through the next day. I loved that image of people being beckoned into downtown in the middle of the night by these fireworks and everybody kind of going crazy, so I wanted to build something around that.

JK: What are you working on next?

NA: I have a collection of stories that I hope I’m done with. It’s with my agent now and he likes it and we’ll see whether a publisher will pick it up. It’s hard to sell a collection of stories. It’s at the “cross your fingers” stage, but the working title is An Index of Human Properties. It’s a collection of stories about engineers and technically minded people. In it, I pursue some themes similar to the themes in The Reconstructionist, especially in terms of how these people tend to approach life in a very rational way, or want to approach it that way, but then they come into circumstances that are not readily solved in that kind of way.

I found myself writing about it because it’s what I know, to an extent. I mean, these are the people that I work with everyday and that I spend most of my working hours with. But I also wanted to write about it because everyone’s very aware of how quickly our world now is changing in a technological sense. Particularly now with the things that are developing quickly on the internet—social media—these technologies are more and more affecting the way that people interact with each other. Even older technologies have a huge effect on how people live their lives, what their expectations of life are, and their expectations of each other and how we deal with each other. So, these engineers and computer programmers and scientists are creating this new world, and yet there’s hardly anyone writing about them. Who are these people that are creating this world that we’re living in? That’s what I wanted to try and bring out.

Only two of the stories have been published so far. One, “Along the Highways,” was in The New Yorker. The other one, the one I mentioned earlier that has a fantastical element, is called “The Beauty Engine” and it was in Midwestern Gothic, issue 1.

JK: What are you reading now?

NA: I’m reading this amazing book by Thomas Savage. It’s called The Power of the Dog and it was published in 1967, I think. I’d never heard of it before, I’d never heard of the writer before. He died a few years ago, but he published at least 10 books, I think, in his life. It’s about a couple of ranchers in Montana in the 1920s. I picked it up just because a friend recommended it. It’s beautifully written, and it has this character “Phil” who’s incredibly complicated and kind of evil, really interesting. He’s at the heart of it. It’s got a fine eye for human character and how people interact. It’s great. I recommend it.

——————

Nick Arvin is a Denver-based author and engineer who has written three books In the Electric Eden, Articles of War, and The Reconstructionist. Arvin earned his MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and also holds degrees in mechanical engineering from the University of Michigan and Stanford. His first book, In the Electric Eden, is a collection of short stories about people whose lives are complicated by the science and technology of everyday life. His first novel, Articles of War, was a book of the year by Esquire Magazine, won the Rosenthal Foundation award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, won the Boyd Award from the American Library Association, won the Colorado Book Award, and, in 2007, it was selected for One Book, One Denver, a citywide book club supported by the Denver Office of Cultural Affairs. The Reconstructionist, Arvin’s latest novel, was published in March (in the US) and was named an Amazon Best Book of the Month for March 2012. Arvin’s work has appeared in The New Yorker, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Salon, Rocky Mountain News, 52 Stories, Midwestern Gothic, 5 Chapters, and 5280.

Hear him read at the Tattered Cover in Denver.

Jacqueline Kharouf is currently studying for her MFA in creative writing, fiction, at the Vermont College of Fine Arts. A native of Rapid City, SD, Jacqueline lives, writes, and maintains daytime employment in Denver, CO. In 2009, she earned an honorable mention for the Denver Woman’s Press Club Unknown Writer’s Contest, and in 2010 she earned third place for that contest. Her first published story, “The Undiscoverable Higgs Boson,” was published in issue 4 of Otis Nebula, an online literary journal. Last year, Jacqueline won third place in H.O.W. Journal’s 2011 Fiction contest (judged by Mary Gaitskill) for her story “Seeing Makes Them Happy.” This story is currently available online and will be published in H.O.W. Journal’s Issue 9 sometime in the fall/winter of 2012. Jacqueline blogs at: jacquelinekharouf.wordpress.com; tweets holiday appropriate well-wishes and crazy awesome sentences here: @writejacqueline; and will perform a small jig if you like her Facebook professional page at: Jacqueline Kharouf, writer.

Jacqueline Kharouf is currently studying for her MFA in creative writing, fiction, at the Vermont College of Fine Arts. A native of Rapid City, SD, Jacqueline lives, writes, and maintains daytime employment in Denver, CO. In 2009, she earned an honorable mention for the Denver Woman’s Press Club Unknown Writer’s Contest, and in 2010 she earned third place for that contest. Her first published story, “The Undiscoverable Higgs Boson,” was published in issue 4 of Otis Nebula, an online literary journal. Last year, Jacqueline won third place in H.O.W. Journal’s 2011 Fiction contest (judged by Mary Gaitskill) for her story “Seeing Makes Them Happy.” This story is currently available online and will be published in H.O.W. Journal’s Issue 9 sometime in the fall/winter of 2012. Jacqueline blogs at: jacquelinekharouf.wordpress.com; tweets holiday appropriate well-wishes and crazy awesome sentences here: @writejacqueline; and will perform a small jig if you like her Facebook professional page at: Jacqueline Kharouf, writer.