The Terrace

You live off the six-lane U.S. State Road 17-92 which cuts through Orlando and one of the city’s major arteries. Even though your building is close to the road, you are not bothered by the traffic; you can barely detect the whoosh of passing cars. This may be because these buildings—the oldest condominium complex in Orange County, erected in the 1950s—are two stories of concrete block, hurricane-proof. You know because you’ve ridden out at least a Category Two here, and plenty of tropical storms.

The buildings retain retro detailing in the porch latticework and New England-inspired names—Gladstone, Kingston, Exeter—which hardly fit the shrubs flowering fire-orange petals, geckos flitting up your porch screens, the lemon tree outside your bedroom which bears fruit in the winter. The complex is notoriously well-kept by the landscapers who descend on Wednesdays, clipping hedges and parading down the sidewalks wielding leaf-blowers like jet-packs, calling to each other in Spanish and Creole, or another Caribbean patois, you’re not sure which. Most of your neighbors have lived here for years. Many are elderly, and a good number are snowbirds—Canadians and Northern retirees who arrive in October and leave around April, with the heat’s descent. But a good number of young couples and singles have moved in recently. You have lived here a decade, and with each passing year, find it more difficult to imagine ever leaving.

The Birds

Sometimes when you are climbing in or out of your jeep, the water birds catch your eye. Herons, pelicans, ibis, and others hunt in the stream behind your building, some so tall they would likely reach your shoulder. You try and sneak up on them, but can get no closer than a dozen feet before they scamper away awkwardly on legs like bent chopsticks, or take flight. Even though the birds are a fixture, they fascinate you. Perhaps it’s the elegant, precise way they hunt in the rushing water as their long beaks hover, then strike, in the weeds. Or perhaps it’s the sheer size of some of them, the uncanny way they can sense one’s approach even as they stare in the opposite direction. They are simultaneously graceful yet goofy, like jabberwockies. Sometimes you find giant white splatters on the jeep’s hood and windshield, dotted with seeds, which ignite a string of under-the-breath curses from your lips because of course you have somewhere to go and cannot stop to get the car washed. But you find it difficult to stay mad at them.

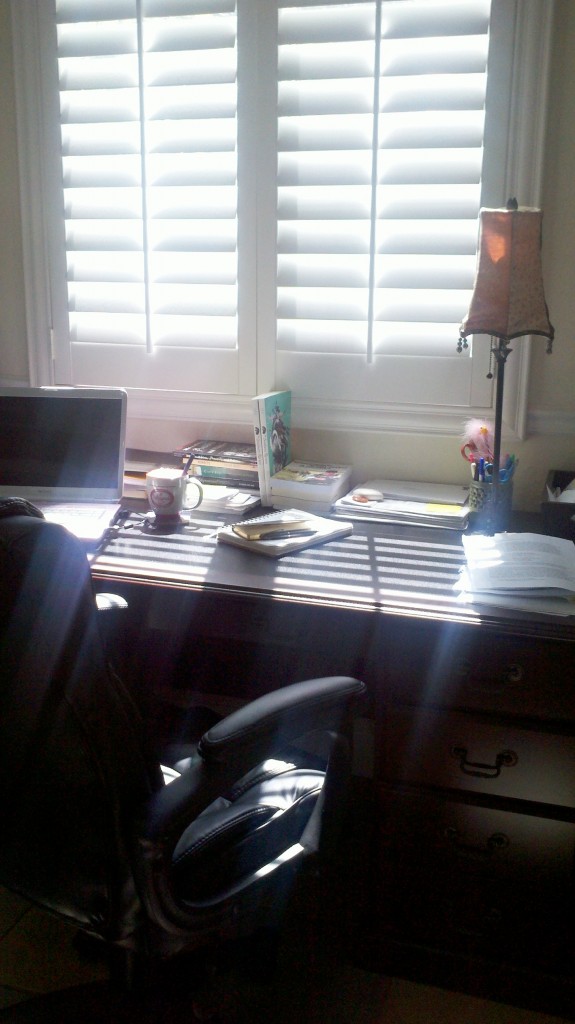

The Room of Your Own

Your office is in the back room which doubles for storage and laundry. While the washer spins and groans in the closet behind you, you peck away on your laptop. So far you have written only nonfiction here, but you are between novels anyway. The vestiges of your most recent project, research for your first novel, are still fixed on your desk—Blood and Capital, America’s Other War, Revolutionary Social Change in Colombia—ominous-sounding titles you would never have predicted yourself reading a few years ago, but that your creative pursuits led you to discover. Literary journals have found their way here, including the final issue of The Southern Review published under the editorship of your friend and mentor, Jeanne Leiby, who died swiftly, shockingly, in a car accident last April. The issues don’t belong on your desk, but you don’t know where else to put them; sometimes you find yourself picking up those with forwards by Jeannie and reading them, some comfort to feel that she is there, yet, within those pages. So every time you replace the issues in their spot, knowing one day soon you will have to clear the desk, make room for new projects, but not wanting to yet. For now, they stay.

Lake Lily Park

You meet someone, a music teacher, at the bar next door. He tells you he’s playing the violin the following night in the park across the street. You decide to check it out.

It’s a balmy February evening, enough for a light jacket or sweater, but as you enter the park’s south side, you pass dog walkers in flip flops and t-shirts, a lone jogger in shorts. Above the lamp-lit brick walk, the Spanish moss dangles from the oaks like lace. This side of the park is vacant, but gradually you round the horseshoe path past the playground alive with children, and the din of music and chatter grows louder. In the daytime you can gaze down among the lily pads in the shallows and spot turtles and fish, but tonight Lake Lily looms dark except for the illuminated fountain in the middle, and the full moon rising in the misty clouds above. A young man steps to the lake’s shore, snaps a photo with his Smartphone. You think of doing the same but don’t. You have never been a fan of stepping out of a magical moment to try and capture it.

Rounding the bend to the far end of the lake is the “food truck round-up,” a modern-day caravan minus gypsies and fortune tellers. Uneven lines form at the truck windows; couples, families, and teenagers stream to the crowded picnic tables with fish tacos and cupcakes. In the center, under a white tent, a new age band strums ambient music—guitar, tambourine, violin, no vocals to disrupt the conversation or mood.

You run into a neighbor and his foreign exchange student, Vika, from the Ukraine, a high school sophomore in glasses who smiles a lot over her burger and fries. She displays a firm grasp of conversational English, and even though you are sitting right beside the band she laughs at the jokes between you and your neighbor, strains to hear your questions but answers them without hesitation. She says it’s thirty below zero back home, that Eastern Europe is experiencing the coldest temperatures on record. She likes American high school because it’s easier. In Ukraine, she studied sixteen subjects a week.

As you rise and say goodbye, you glance at the music teacher—he’s on violin, nods in return, but a restlessness stirs within you. Perhaps it is the ambient music, which alternates between uplifting and melancholy, as now, matching the cozy din of the residents milling about the brightly lit trucks, young and old, married and divorced. You leave and walk around the lake, but there is no escaping this feeling of having one foot in an old chapter that is closing, and another in the new, opening up; you have been in this love-limbo before, this splitting of self. You are almost, once again, single.

The Dance Studio

You bustle into the studio at nine-thirty, water bottle in hand and dance bag bulging with your tambourine and gypsy skirt. Lively Indian music stops and starts from the class in medias res, and when they file out at ten, skin glistening and faces flushed, they talk of costumes for the upcoming show—wrong sizes ordered, jewelry to be borrowed, sewing to be done. They are the professional Belly dance class; many of them have been dancing for years, grew up taking ballet and jazz. Some dance at various themed restaurants in Orlando, for Disney and Universal Studios. You had one semester of ballet, but somehow you are here. At twenty-seven, you discovered your gift for dance, and now, like writing, can’t imagine giving it up.

Tonight, your troupe practices tambourine first—a rollicking number with spins and changing line formations. You split: one half of the group performs for the other half, who sits along the mirror and scribbles critique on scraps of paper. Then one by one, you fire off feedback (“The push backs are getting lost, make them bigger” and “Keep energy in the arms! No chicken wings”). When your turn comes to the galloping music, your coin earrings flick against your neck. Your timing is good. All you need is to slip fully into the dream on stage, and you will be great. The same rules for fiction apply to dance: forget the self, and the art shines through.

Then you run through the Persian routine. The green velvet and gold-trimmed costumes have arrived, Renaissance style with bell sleeves, complete with gold tiaras and veils. You look like queens, or at least ladies-in-waiting. This dance is sweet, graceful, totally unlike the other. Just after eleven, you finish. Before exiting, you remove your checkbook to pay for the costume. Your stomach squeezes as you write the amount. What is the cost of fantasy? Are you living the life of a Winter Park housewife as someone close to you recently claimed, the bourgeoisie woman in her prime, claiming she’s an artist? Should you stop all of this, and focus on paying the rent?

You should, argues the logos mind. But how can you? The stronger half of your brain, the half that is toned and strong from crafting critical essays, thirty stories, and a novel these past five years, is as sculpted and agile as your limbs as they carry you to your dented, shit-splattered jeep in the night. That brain and body, blood pulsing with adrenaline and spirit as you sweep through the barren streets, wails no, you cannot stop. To stop is death.

You pull into the complex, park in front of the lemon tree. Climbing from the jeep, you are grateful for the spotlight illuminating the lot vacant of persons, or birds—where do they go at night, the spindly-legged hunters of the stream? Through the trees, laughter and loud voices escape from the bar next door. The scent of night-blooming jasmine trails after you, up the sidewalk; the Canadian couple, down for vacation, sit outside the unit beside yours, smoking, cradling glasses of red wine. You are back at the condo, alone.

—Vanessa Blakeslee

—————————————

Vanessa Blakeslee’s fiction has been published in The Southern Review, The Good Men Project, Ascent, and The Drum, among many others, and her short story “Shadow Boxes” won the inaugural Bosque Fiction Prize. She has been awarded grants and fellowships from Yaddo, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, the Ragdale Foundation, and recently was one of twelve writers selected by Margaret Atwood for her 2012 Key West Literary Seminar workshop, “The Time Machine Doorway.” Vanessa’s nonfiction and reviews have been featured or are forthcoming at Numéro Cinq, The Paris Review Daily, The New Republic, KR Online, and The Millions, to name a few. In addition to writing, she’s a professional dancer with the Orlando Bellydance Performance Company in the troupe Gypsy Sa’har. Find her online at www.vanessablakeslee.com and at the Burrow Press Review blog, where’s she’s the resident “Shimmying Writer.”

Love these WILLH features, and this one especially. Beautiful words/phrases/images, Vanessa.

Wonderful essay, diving like a pelican from place to person, then coming up to look around some more.

I enjoyed reading your passage. I grew up in maitland and came across this looking at some history of the area.