I spent the summer of 1968 in Freiburg. Martin Heidegger was still alive, living in a retreat in the Black Forest in an odor of disrepute on account of his Nazi sympathies during the war. I had a fantasy that I would meet him hiking in the woods. I never met him. I did meet Friedrich Von Hayek, the great economist, but he was easy; he had an office at the university and I walked in one day with a mutual acquaintance and shook his hand. My brush with history, my personal relationship with the god of Paul Ryan and the austerity-cats of the Republican right.

Heidegger is a particularly difficult philosopher to read because he thought he was inventing a new language to talk about the thing he couldn’t talk about. You can’t tell sometimes if he is being mysteriously impenetrable or just impenetrable as in opaque. He had a vast nostalgia for Being which he thought of as something we couldn’t access by perception or thought. This vast nostalgia seems sometimes to have been more felt than reasoned; he was of that generation who still mourned the passing of the Greek gods. He also slept around a lot and had a more or less open marriage with his wife, Elfride. Somehow his nostalgia for a thing you can’t reach and his many love affairs seem comically and humanly self-contradictory. He is ripe for literature.

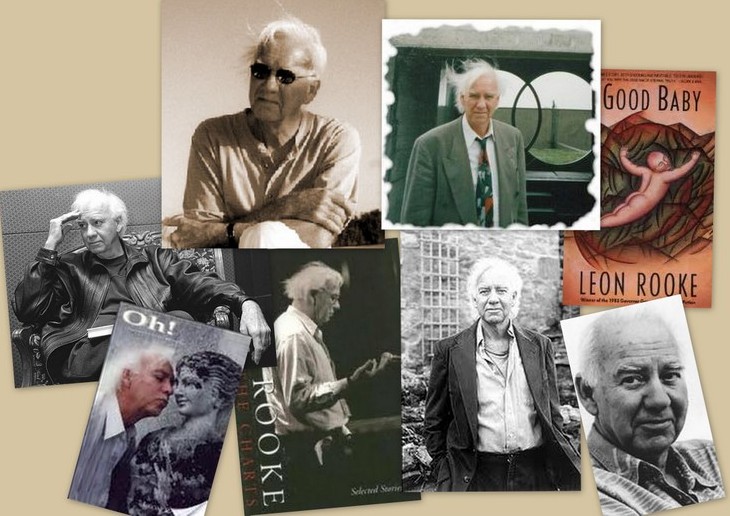

Enter Leon Rooke.

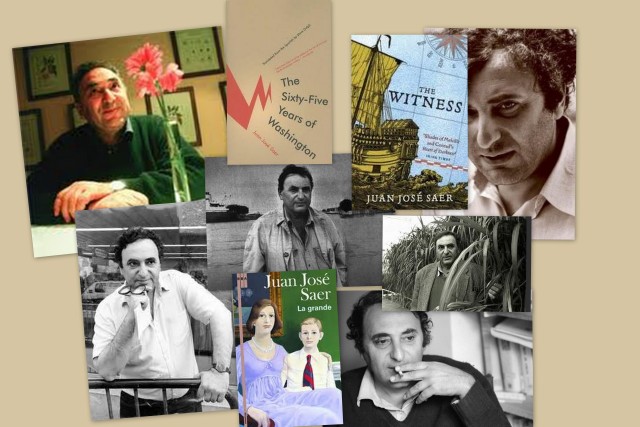

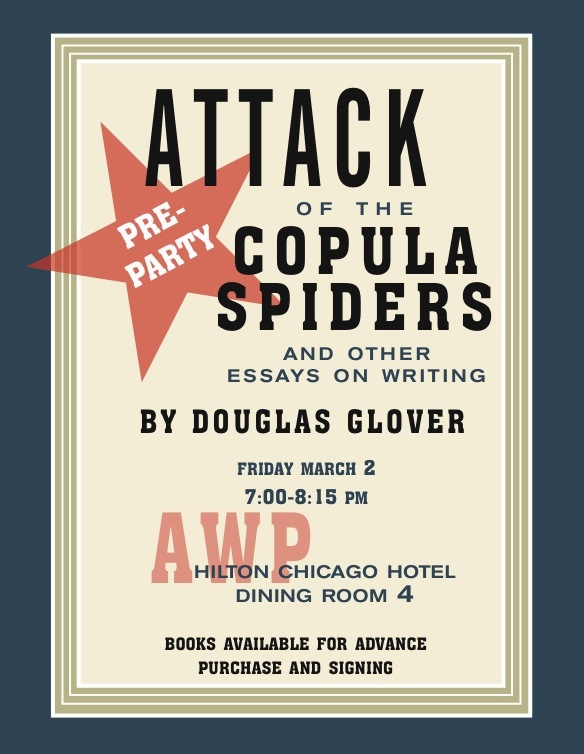

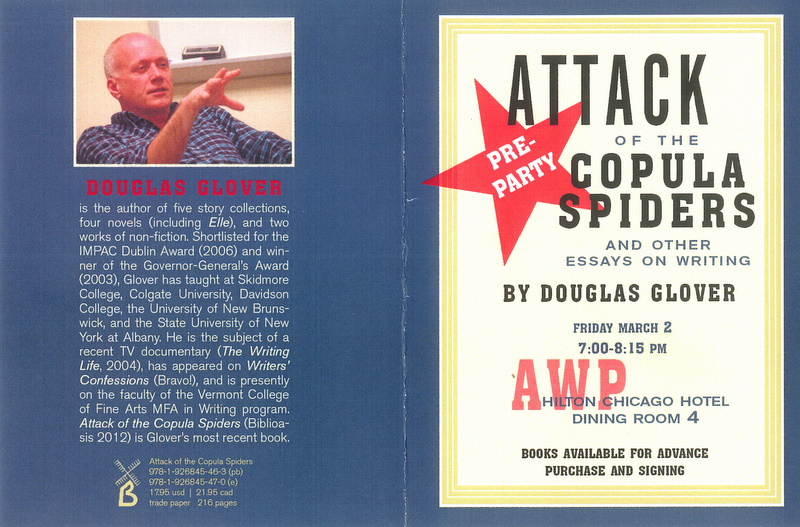

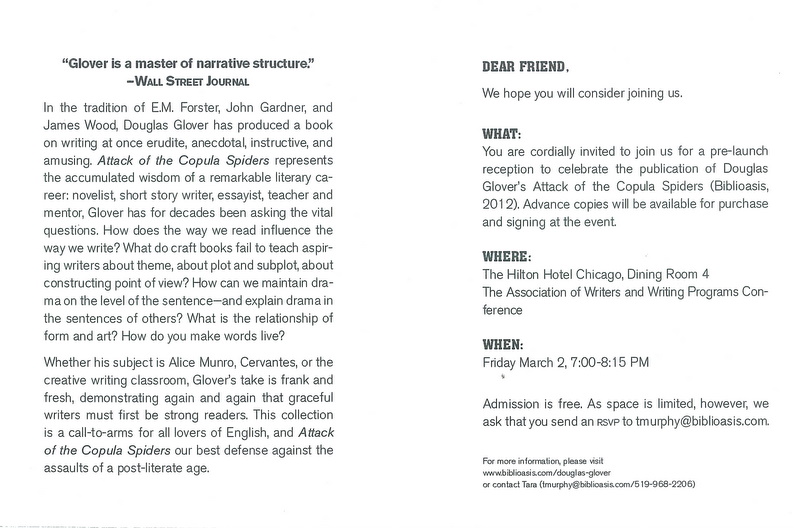

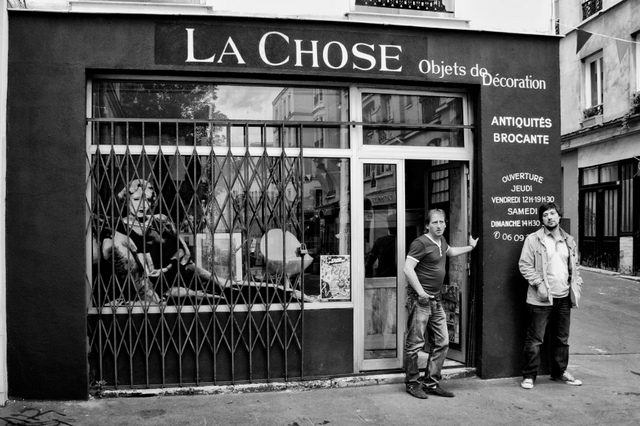

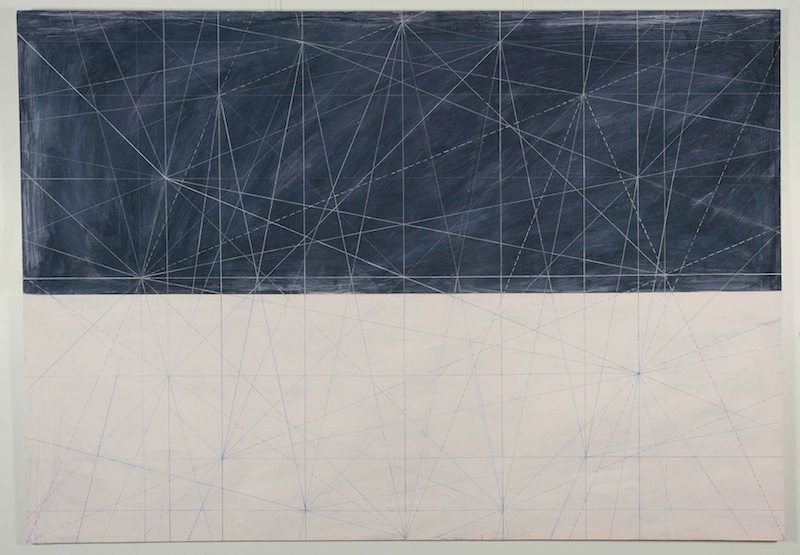

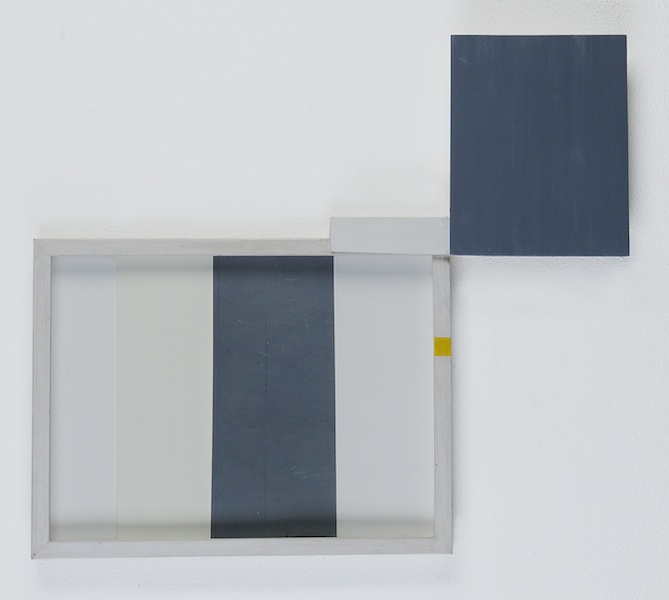

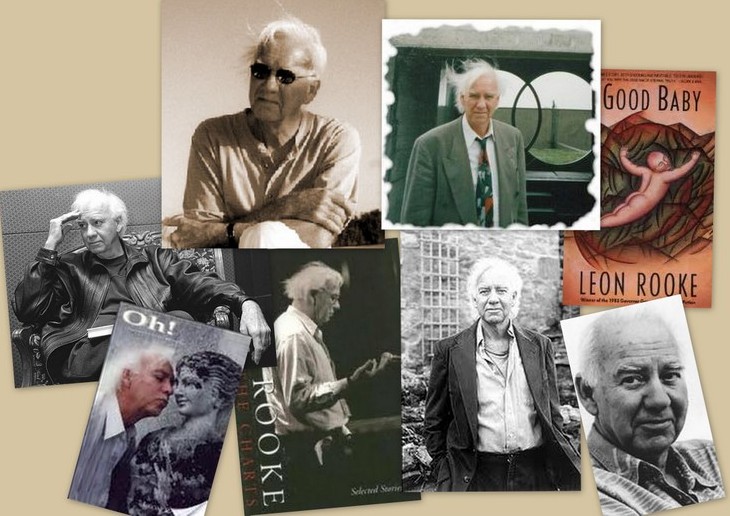

Leon Rooke is an old and dear friend. He was in my head long before I met him because of his books, Shakespeare’s Dog in particular in those days, a novel that has stuck with me as a license and an inspiration — William Shakespeare as observed by his dog (who is telling the story), a brilliant book, a tour de force of point of view construction, an example of how literature thrives by making things strange. I put Leon in Best Canadian Stories regularly (as often as Alice Munro) over the decade I edited that anthology. I’ve reviewed his books at least a half-dozen times. I wrote an essay about his (also brilliant, eerie, and wonderful) novel, A Good Baby, which you can find in my book of essays, Attack of the Copula Spiders. Rooke was born in North Carolina but lives in Toronto. He has an actor’s voice and presence and is an amazing performer of his own work. He’s also a painter — we have been lucky enough to publish images of four of his paintings on NC.

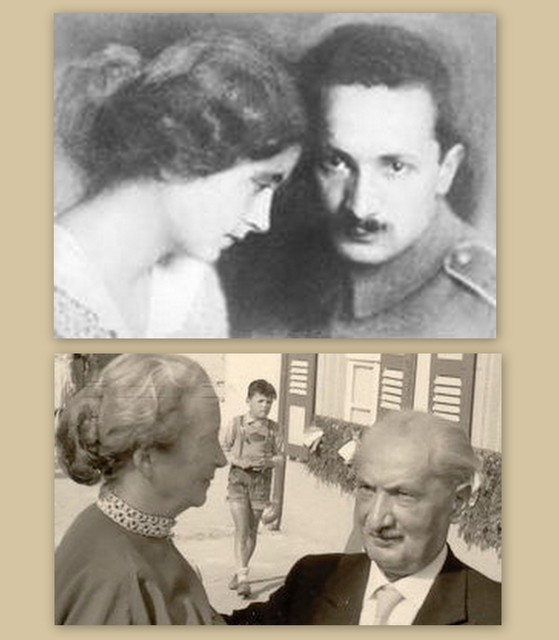

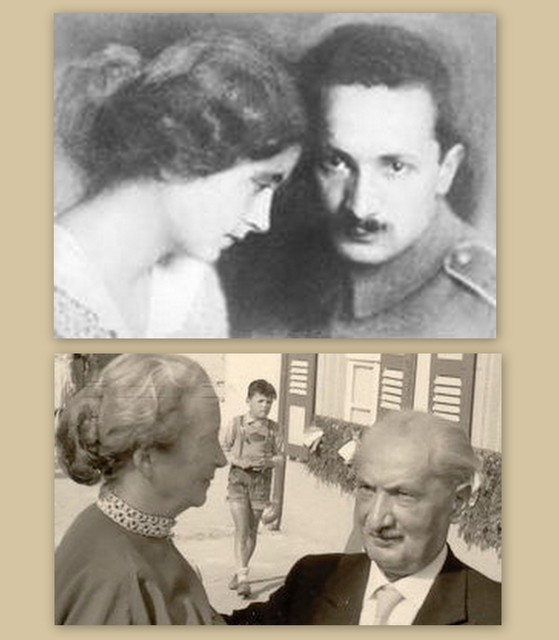

In “Heidegger, Floss, Elfride, and the Cat” Leon Rooke gives us Heidegger with his pants down (metaphorically), straining to compose the impenetrable prose of Being and Time while shuttling to and from his lover’s house and fending off the jealous and passive-aggressive intrusions of his long-suffering wife (I have inserted photographs of the real Heidegger and Elfride below). All this is relayed through someone named Floss, another one of those odd point of view inventions Rooke is so good at. In this case, Floss might be a philosophy student reading Being and Time in a library or he might be Heidegger, or rather, I think, Heidegger’s Being (which we might have called his Soul in the old days). Heidegger, of course, can’t know Floss, but Floss knows everything about Heidegger. And when the story is done, Floss trundles home to his wife and kids (being Heidegger’s Being is like a job). And, of course, it’s very late and I might have got this wrong.

As far as I know, no animals were harmed during the composition of this story (despite what happens to the poor cat).

dg

§

Lights that flickered, curtain at a certain pitch in the summoning, the rendezvous with Frau Blochmann now concluded, Heidegger clamps his trouser legs and bicycles home.

Floss withholds opinion on the Master’s affair with the eminent colleague, which he knows will continue another few decades. What he wonders is what Elfride will say when the philosopher king comes through the door. That Jewish bitch again? Or will she say nothing, having just dispatched her doctor friend through that very door. This love business is a bit tiring, is Floss’s thought. Get back to work, he tells Heidegger. Not that such is required. After swallowing a bit of Elfride’s tasty stew Heidegger will be at his desk. Being and Time, thinks Floss, page 355. Quote, Resoluteness, by its ontological essence, is always the resoluteness of some factical Dasein at a particular time.

Floss, in his cramped library carrel, has no argument with that. Well and good. Floss and resoluteness and Heidegger, Floss believes, are one and the same.

They are together, he and the Freiburg sage, working the deep trench.

Heidegger now writes, quote, The essence of Dasein as an entity is its existence.

Without entity, no essence: well and good, remarks Floss to himself. Particles afloat in space, what purpose they?

Quote, The existential indefiniteness of resoluteness never makes itself definite except in a resolution. Page 346.

Here Floss wants to say Hold the phone. Floss wants to put his foot down.

Floss’s mind is rapidly scribbling notes to himself. These notes are scratching like a dog inside Floss’s brain. Hold the phone is but one of the dog’s bones.

Floss’s index finger is rapidly scanning the lines, speed-reading Heidegger as the master composes. Are not he and Heidegger that close? Are they not twinned with respect to Being and Time? Are they not brothers?

Floss can quote aloud, at any time, Floss can, any one of Heidegger’s current or future thoughts. The text is spread open on the desk for company only.

Photographic. That’s what Floss’s mind is.

Never mind that he has scribbled into his notebook the erroneous page reference. His hand did. Floss’s mind knows the difference.

Not 346. 355. Floss has jumped ahead. He always knows where Heidegger is going; often he arrives at the destination while the King of Thought is still clearing his throat.

Quote, Only by authentically Being-their-Selves in resoluteness can people authentically be with one another.

Ah! Floss thinks. Let’s not get too, you know, personal. Like.

In Floss’s view this statement is another Hold the phone. This is Heidegger fighting a headwind.

That someone has just this moment walked into Heidegger’s study is radiantly clear to Floss. Being with one another is an untypical Heidegger sentiment. The Master has been thwarted in his goals. Ergo, the line’s impurity.

Who is the culprit this time?

Excited, Floss thumps his knees.

Elfride, of course.

This is Heidegger being influenced by Elfride. This is the wife calling the tune. It is Elfride saying, If you are going to be with me, then be…with me.

Floss can see Elfride hovering over the great man’s shoulders. He can see her whisking dandruff from the great man’s shoulder with a tough whisk broom.

—Don’t mind me, Elfride is saying.

Heidegger doesn’t like any of this. Naturally, he doesn’t. Her very presence fills him with distaste. She has destroyed his flow of pure thought. Be with one another? How has that monstrous phrasing got onto his page?

Four a.m. Heidegger never sleeps, that explains him. But must Elfride do her dusting at this hour?

Floss thinks not. Floss thinks Elfride must have something up her sleeve.

—Dearest soul, the great man says — can’t you go away? Can’t you leave the room and quietly close the door?

—You know what happens if I don’t dust, don’t you? Elfride says.

Heidegger doesn’t know what happens if Elfride doesn’t dust. He is pretty certain Elfride means to tell him.

—Can’t you make a guess. Oh, go ahead. Go out on a limb.

Heidegger is thinking he has always been out on that limb. He was out there first on the limb with the Jesuits when he was a boy, then with Husserl, the so-called father of phenomenology; he was out on the limb with Elfride, then with Hannah, then with Elfride and Hannah jointly. And don’t forget colleague Blochmann. Occasionally the Stray Other. Now he is back on the limb with Elfride. Elfride is dusting the limb.

—I do not intend to engage in your theatrics, dearest soul, he says. I intend to sit here and work on this passage on page 355 until I get it right.

—It’s right, dear one, Elfride says. I’m here to tell you it is already right. You get it any righter, then I won’t know what to do with myself.

Floss, hearing this exchange, leans back in his tight carrel chair. He crosses his arms over his chest. He closes his eyes.

“Don’t let me interrupt you,” Floss says.

Heidegger spins his head. Elfride ignores Floss. Floss is a pest; he pops in at inconvenient times; otherwise, he is nothing to Elfride.

—Keep out of this, Floss, she says.

Heidegger sighs. These sighs are magnificent. They express his full contempt of those who would make the philosopher’s already impossible task that much more difficult.

Elfride, normally the most anchored of women, is subject to flights of fancy. Now she’s whisking her broom at vacant air. She has even given that vacancy a name: Time Being. There was a time, Floss recalls, when Elfride was more besotted with Heidegger than some now assert is the case. It is all that Hannah’s work. Months before Elfride and her future husband met Elfride had carried in her pockets notes destined for the magician of Frieburg. Don’t deny it. Yesterday I saw you looking at me. Or: Last week I blocked the doorway and without a word you swept by me. Or: I beseech you. Love me. She still retains these undelivered disintegrating missives under lock and key in a wooden chest buried beneath the floor. They prove her love. They prove her love existed prior to his. This makes her proud. Not even the great can be first in every regard. These notes will be published after her death. The instructions are contained in a sealed envelope affixed with her granddaughter’s name. Not in this envelope or in the locked chest is the narrative describing the gypsy fortune teller’s role in their haunted lives. Well, are not all lives haunted, Floss, who has never loved, reminds himself.The gypsy said to Elfride, On the first rainy afternoon, following your economics class, stand beneath the first blooming tree your steps venture upon. The lover meant for you will appear. Cold rain dripped, afterwards she caught a cold that endured through many weeks, and periodically through each wheeling year, this existing as nothing because love’s astonishing light penetrated the drooping boughs and stormed her heart. Heidegger, under a black umbrella, indeed appeared. Through wet lashes he imagined he saw a dying tree where nothing had stood days before.

—You. What is your name?

—Elfride Petrie.

—Why are you standing in the rain?

—Waiting for you. I am your fate.

Heidegger believed in fate as he did in Plato, with suspicion, particularly with regard to the monumentally salient question What is truth, but he was impressed. She was also pretty, though with rain pouring over her face he would reserve opinion on that. Yet when this schoolgirl fitted her body against his, his heart which was three quarters stone fragmented and certain sounds issued from his mouth never until that moment heard by himself or by any other. Fortunately only children on a dilapidated school bus, there to witness ancient Marburg splendours, were present, and they were too distracted to absorb any image of the historic coupling. This was because rain had become sleet, sleet had become snow, which in minutes had blanketed the lovers, flakes ascending and descending a second and third time, and then repeatedly, in abstract harmony with their movement. Floss, who was there and could have sought the better view had he been that kind of person, was mostly concerned with Heidegger’s black umbrella which gusting wind ripped into sundry pieces, the cloth flitting hither and yon like unruly crows, if crows were ever to attempt flight in such weather.

Heidegger has put down his writing pen. He is leaning back in his chair. He is crossing his arms over his chest. He fits his tongue beneath the upper lip; he can see clearly his thick Fuhrer’s moustache. The sighting gives him strength, although he distinctly prefers his own. He is reminded that theirs is a nation-building task. The moustache renews him in the impossible goal.

He sighs anew, leaning further back. He closes his eyes.

His sighs now, however, are obviously feigned. They exist merely as an admonishment to his wife. Feigned, they express his resignation. His disappointment with married–the assailed– life. The sighs are meant to convey to Elfride that he has given up. How can he work with a loudmouth duster in the room, chattering non-stop?

Gone from his head is that trail he was tracking re resoluteness.

But that quickly does his mind seize again upon the trail. His shoe soles hit the floor. His burden has lifted. The pen flies into his hand. Once more he is at work. He is already scribbling again.

He is scribbling, Floss thinks, quote, The resolution is precisely the disclosive projection and determination of what is factically possible at the time.

Hold the phone, Floss is thinking. The projection is termed disclosive only because the thought has just this second revealed itself to the sage. Ditto, factically.

But Heidegger is breaking his pen’s point underlining this significant line. It is imperative that the line be printed in the italic. If the line is not set in the italic then readers fifty years from now, speedreaders like that dunderhead Floss, will fly right by it. They will be blind to its pertinence, as he himself is blind to the dust, the dandruff–as he would wish to be blind to Elfride’s galling presence.

—That’s good, Martin, Elfride says. I love that factically possible line. It makes me break out in a cold sweat.

Indeed one of them in the room is sweating, though it isn’t Elfride. Heidegger is sweating because writing a new philosophy, bringing the axe to old traditional philosophical walls — that, mein Fuhrer, is hard work. Plus, there’s the other problem: the window, the cat. How hot and stuffy this room is. If he raises the window, he will be wasting heat. Heat the Volk must not waste. Only a Jew saboteur would waste the nation’s heat. So he is stymied on that front. Yet — and now he is getting to the essence of the situation — yet if he raises the window, the simple solution sans heat, the loathsome cat which always plops itself down on the sill, will come in. Thus, he keeps the window shut. He sweats.

Architects, he thinks, truly are a repellent tribe. They can get nothing right.

Floss swings in his chair. His shoe soles strike the floor. He sees Elfride poised. Resolute Elfride is ever on the job.

—Were you saying something, darling? says Elfride. It isn’t the architects, it’s me. Don’t blame the architects for your stinginess. Blame the war. Or better yet, yes, blame me.

She parades curvaceously around the sage’s desk.

—Although of course, she says, you would be perfectly justified if you blamed the cat. I’m with you there. I hate that cat. That cat is the ugliest creature I, for one, have ever seen. Are you for two — if I may phrase the question so? — in thinking that cat is the most frightful creature ever to walk on four legs?

—Three, Heidegger says. If we are to speak of the cat, then let’s speak precisely. The cat has but three legitimate legs. The fourth, as you can distinctly see, is so foreshortened as to scarcely exist.

—Foreshortened? says Elfride. Do you mean to say the leg in question existed that way in the womb? Perhaps in the very exchange of seed? Oh, I think surely not foreshortened, because I clearly remember that leg was perfectly normal until you crushed it when you caught the cat coming through your window.

Heidegger lowers his head. He kneads his brow. He is thinking, I have stayed up all night for this?

He is thinking, Hannah, thank God, was not a chatterbox. Her head was on my chest whenever I spoke.

—Yes, darling, Elfride is saying. As much as I despise the creature, it is criminal what you have done to that cat. You all but pressed that cat flat. Martin, I hardly know what to say. I hardly do. I am speechless, listening to your infirmity on the subject of that cat.

Floss sees the philosopher’s eyes narrowing. He sees him looking with utter hatred at this wholesome, proud, meandering wife. Heidegger’s defence collapses. Elfride has described the scene exactly as it occurred.

—It was an accident, Floss says.

—It was purely accidental, Heidegger says.

Elfride snubs this excuse. She whisks it away with her broom.

Floss has his attention elsewhere. He is focusing on the sleeping cat. The cat, to his eyes, has altered itself somehow. That the cat suffers deformity is true enough. But it is no longer the bony, undernourished cat. The cat has been eating. It has found food somewhere. The cat is fat.

As for Heidegger, already he is scribbling again. Quote, When what we call “accidents” befall from the with-world and the environment, they can be-fall only from resoluteness.

Floss forsakes his study of the cat. Hold the phone, he says. Hold the phone. Hello, hello. Bravo, my friend.

But Elfride’s broom is stabbing the air.

—You could kill the cat, Elfride is saying. Yes, my lamb, you could finish the job. Then you could raise your window, if only for a moment. Surely not a great deal of our precious heat would escape if you raised your window for one mere moment. Our war resources would not be sorely depleted. Fresh air, Martin! Glorious health! With the window open, even so little as a tidge, you would not be forced to wrestle there in heavy sweat. You could be comfortable. Surely your work would go better if you were comfortable. Kill the cat, my good soul. With the cat dead, your Being and Time will be concluded in nothing flat.

—Enough, Elfride. Enough!

—Shall I kill the cat for you, Martin? I would be happy to kill the atrocious cat if you tell me you believe I should, and can morally justify my performing the act. Issue the cleansing command. Think! She is only a cat.

—She? That cat is female?

—Oh master, groans Floss.

—Yes, and rather resolute, by the look of her.

Heidegger sinks low into his chair. He hoods his eyes.

—Are you done, Elfride? Dearest soul.

—Done?

—Yes, done. If you are not done, Elfride, then I am leaving my desk. I am leaving my house. I will walk this night all the way to my cabin in Todtnauberg, if that is what it takes to be quit of your tongue.

Floss, at his desk gnawing a fingernail, allows himself a smile. The sage is tempting fate with this mention of the cabin, of Todtnauberg. He has stepped with both feet into Elfride’s trap.

—Todtnauberg? Elfride says. Your cabin? But, darling, the cabin is mine. True. I gave it to you. But quit my tongue? Oh, heavens, you can’t mean I have disturbed you. I rattle on, certainly, but only because I know how much my rattling improves your mood. If I did not rattle, you would go about eternally under your famous black cloud. You would never be able to look anyone in the eye. Your students would hardly hang on to your every word. Oh, I think it is fair to say, Martin, that without me and my tongue, and my Nazi boots, and just possibly the cat’s presence at your window, you would never get your work done. You would never write a line. Most assuredly your opus would never be completed. Fame would elude you. Not a person outside Frieburg would ever have the pleasure of hearing your name. You can admit that to yourself and to me, can you not? I’ll not hold it against you. You do not have to prove yourself to me, not ever. Certainly not the way you had to prove yourself to that schoolgirl, Hannah Arendt. And to take her to my cabin in Todtnauberg to prove it, well, my word!

—So that’s it, is it? That’s what this eternal dusting is all about. This mouth disease. So you can harp night and day on my little Hannah fling.

—Little, darling? What would poor Hannah think if I repeated to her what you have just said? Did you not write to her that she was your life? Did she not reply that you were her every heartbeat? That your paths would haunt each other until the death? Oh, I think so, darling. I believe those were the two sweethearts’ very words. ‘My homeland of pure joy.’ Was that not your latest encomium?

Floss applies a handkerchief to his eyes. His eyes are wet. They ever get so each time he sees Hannah and Heidegger together in the cabin at Todtnauberg. Strolling together after class under the singing trees. The decades of love to come. How thrilling it must be, Floss thinks, to possess these loves.

Still. Still, Floss altogether shares Jasper’s view when it comes to that Hannah relationship. Resolute, yes, but messy, messy. Cataclysmic love: Hannah defending him at the French de-Nazification committee hearings: scrambling to hawk his manuscripts to Columbia: through the years never one syllable from the master’s mouth as to the beloved’s own work which he read in secret and secretly believed ephemeral if not deliquescent. Her head ever lowered to his chest.

Elfride is thorough. Not all has been said:

—Or perhaps the precipitation in your eyes has as cause your forthcoming tart Princess Margot of Saxony-Meiningen. Will your rendezvous signal this time be flashing lights or will it be your shades hanging at a certain depth, as was the case with banal Hannah? Which? Will she hand-copy your every hour’s text, as I do?

Floss is astounded. He is giddy with excitement. He has not heretofore perceived that Elfride’s capacity to see into the future matches his own. He sees her now, as one day she doubtlessly will, hands clasped in an unrecognized lap, confused by the vague sense of warfare between aching joints, an old woman of 92 awaiting death in a caretaker home. Will she see her two sons on Russian soil, prisoners of war? Has she yet seen the Delphic oracle rescuing from rubble manuscripts housed in what previously was a Messkirch bank? Hiding them in a cave?

Not at the moment, in any case. At the moment what both Elfride and Floss are seeing is the Master frantically bicycling 16 miles to Todtnauburg, flinging off his clothes, now dressed only in an absurd Tyrolean cap, Elfride, Hannah, the Princess, and scores of other women panting in pursuit, flinging off theirs. For Floss, madness promotes the vision. For Elfride, a confirmation of enduring love.

A thousand letters, cards, over the decades, informing Elfride where his Divineship is, not one suggesting who he is with. What a challenge this marital devotion, these conjugal splits. Send in your party membership, dearest soul, thinks Floss. In resoluteness is strength.

“Get back to the cat,” Floss tells Elfride. Forget Hannah. The cat, after all, has meaning; it is both a real and a symbolic cat. In light of the great man’s post-war silence on the issue of certain atrocities, personal betrayals, I could tolerate additional intimate details re his treatment of the cat.”

—Shoo, shoo, says Elfride. Stop harassing me.

Heidegger is distracted. Once more, Elfride is communicating with vacant air. But perhaps this is good. Perhaps her nasty obsession with Hannah has for the moment exhausted itself. Elfride, he thinks, with her everlasting can of worms. Essence of spite. Why can’t my two great loves, my sprites, be friends? I must see to that, however imbecilic it may appear.

He looks at the cat, asleep on the window sill. Even curved like that, one can see the leg’s deformity. The crippled spine. The cat should be killed. It is doing that cat no favor to let it live.

He would give Elfride the order. He would say to her, Elfride, kill the cat! Do it now.

But he and she are locked in this struggle. They are irresolute. The cat, if it is to die, must die under Elfride’s own initiative. If he were to give the order, the cat would ever survive intact in his memory. Whereas, if she killed it outright, slicing its throat with a knife from the kitchen or beheading it with the hatchet on a woodblock in the back yard or merely trampling it to death, then the cat would be gone forever. It would disappear totally and entirely from his mind and from the world. Its essence would have been annihilated, its entity denied.

He thinks: what Elfride is hoping is that the weather will get extremely cold this winter — Frieburg under ice, the cat stiff as a rock in the freeze. Certainly there is not the remotest chance that she will allow the cat inside the house.

Unless she does so in punishment of me. Unless she does so out of revenge for my taking Hannah to Todtnauberg. Such a stupid impulse, despite its having led to excruciating reward.

One, it had led Hannah out of drabness. It had transformed her overnight into a bewildered passionate vehicle of sex. Wrought, her mind had unloosened, her brain cells uncoiled.

God forgive me the moments I even have wondered she wasn’t the better thinker than me.

Heidegger is close to tears. The shame of this.

—Oh, she’s bright, Martin, Elfride says. I have never denied you her brightness. But — she snaps her fingers — she isn’t you.

Floss leans back in his chair. He removes his glasses, polishes them. Elfride’s face is flushed. Always, with that flushed face, any wild remark is apt to burst from her mouth. He wants his glasses clean, that he may see her clean, when next she speaks.

“Tip the scales, Elfride,” Floss says. “Show the great man how bright you are.”

—Martin, darling, Elfride says. She is laughing. —Look what I am doing!

Martin has been cleaning his glasses.

Floss, putting on his glasses, sees Heidegger putting on his.

As for Elfride, Elfride is at the study window. She is poking the cat with a stick. Heidegger keeps the stick there for that very purpose. Enter a line in Being and Time, then jump up and poke the cat. Enter another, poke the cat. Day after day, poke the perfectly stupid, ever returning cat. That is how his opus is being written: Elfride’s dusting, Eflride’s interventions — but whenever alone he has been poking the cat.

So Floss figures. Floss has figured it out. Just as he has figured out — flipping the pages, speed-reading the familiar text — the nature of the breeze. He must wipe his fingertips of glycerine, that’s how much speed he needs. He has learned the dark secrets of this book. Floss knows precisely each line, each phrase, where Heidegger has got up, flung himself across the room, picked up his stick — tortured the cat.

But today, to Floss’s mind, there is something different about this cat.

“A moment, Elfride. Consider. In my view, that’s a pregnant cat.”

But Elfride is in action. Elfride has the stick. She is poking the cat.

—-Da!(poke) Da!(poke) Da!(poke) Da!

The cat is squalling; it is meowing, hissing. Clawing the glass. It can’t get in, it can’t get out.

Heidegger, cannot, will not, look. He turns his back to this scene. He claps hands over his ears. Elfride is capable, reliable. When the deed is done she will dispose of the corpse. He need never be appraised of the how or where. Philosophy need not concern itself with a being’s single specific fate. It has steered fathomless circles since the Greeks established the course. Well done, Greeks. Now those old walls must crumble. With certain exceptions, work to date has been rubbish in the wind. The ground is soggy, diseased, repellent: it releases a fetid odour. Original thought is now required. Already the cat’s presence, Elfride’s resoluteness, is slipping from his mind. The pen flies into his hand; it flies across the page. Quote, ‘Irresoluteness’ merely expresses that phenomenon which we have interpreted as a Being-surrendered to the way in which things have been prevalently interpreted by the “they”. Sweat pours down his cheeks. He pauses. He wonders if he may permit himself a footnote excluding Plato, Holderlin, Nietzsche from this “they”. Probably so. Why promote their cause?

He works on. He is unaware that Elfride’s Da! Da! Da! has catapulted into shrieks. Something about the cat. Something about something inside the cat. Let her deal with the matter. The cat is a household problem. That’s what marriage is for. For wives to deal with them.

Floss isn’t fooled. He knows Heidegger’s deeper thought: This wife, this hellcat, distorts the providence of being.

“Do you wish to whack the cat, Martin.” Elfride is whacking with each shriek.

Floss cannot sit still in his chair. His every nerve is shot. He cannot witness any more of this. He is shouting at Elfride, “Put down the stick! Filthy Hun, put down the stick!“

Already she has dropped the stick. Blood has splattered on the carpet, on her lovely night-dress. Her hands are covering her face. On the sill the dying cat is wrenching its body one way and another. Gore is leaking from the torn fur. Blood pools on the window sill. A slimy wedge of kitten protrudes beneath the crooked tail.

Never mind. Soon, reaching towards sixty, Heidegger will be out on the hinterlands with young and old, digging trenches to delay the advancing enemy. Floss hurriedly assembles his books. He hitches the backpack over one arm. Rushes down the stairs. The library is exceptionally well lit. Fluorescent tubes quiver and spit. In the entire building no other individual is stirring. The universe is silent. Dawn has arrived, an ascending quilt. His own cat will be crying. His cat will be saying, Why have you not been here to let me purr in your lap? What have you been doing? His wife and children will be in tears. Where have you been? Who are you? (Dearest soul), resolute being, explain yourself.

— Leon Rooke

———————————

Leon Rooke has published more than 30 books, including novels, short story collections, plays, anthologies, and “oddities,” and more than three hundred short stories. Rooke’s many awards include the Governor General’s Award for Fiction (for Shakespeare’s Dog, 1985), the Periodical Association of Canada Award for the English-Language Paperback Novel of the Year (for Fat Woman, 1982), a Pushcart Prize (1988), the North Carolina Award for Literature (1990), and the Canada/Australia Literary Prize in 1981, for his body of work. Also the W. O. Mitchell Literary Award, for his writing and his mentoring, and the ReLit Short Fiction Award. Rooke has taught at more than a dozen Canadian and U.S. universities. He lives in Toronto.