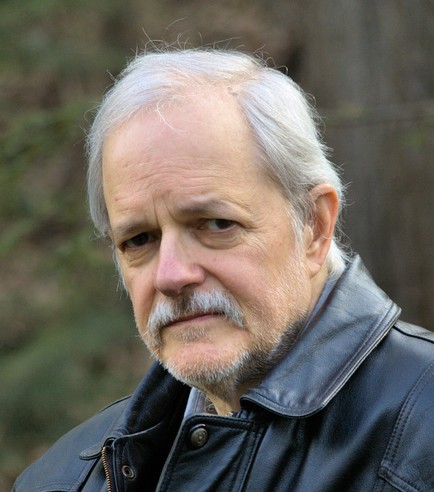

Author photo by David Penhale.

Author photo by David Penhale.

Here’s a very smart, fresh, angular essay about Martin Scorsese, a recapitulation of his films, his trajectory in the art, but crucially focused on the idea and markers of success (material and otherwise) and tainted success, the kind of success that betrays authenticity. What makes this essay especially fascinating is that the author writes from the perspective of a Catholic intellectual, a stance not necessarily popular in this arid post-liberal climate we inhabit but nonetheless full of hermeneutic vigor. Scorsese is a lapsed Catholic, but a world view founded on ideas of sin, the fall, and redemption suffuses his gritty films—at least, when the case is made, it makes sense.

Philip Marchand is an old, old friend. See his complete and charmingly self-written biography below the essay. Suffice it to say here that he wrote the best biography of Marshall McLuhan ever, a book that I revisit and treasure and not just for what it says about McLuhan—it actually helped me understand how subplots work in novels. And he also wrote a gorgeous book called Ghost Empire about the great French explorer La Salle (but also about the author himself, the history of North America, and the decline of the west, which yet managed to be amiable and friendly and charming). Here’s the opening of a review I wrote at the time:

In Ghost Empire, Philip Marchand’s new book about the voyages of the great and peculiar 17th century French explorer Robert de La Salle, the author doesn’t tell us much that is novel about La Salle. But in recounting the daring explorer’s epic wanderings Marchand manages to compose an amazingly fresh, surprising take on North American history, French-Canada, Catholicism, and the author himself, a faintly quixotic character, bookish, erudite, and appealingly self-ironic.

dg

.

Martin Scorsese ends King of Comedy in the same way he ends many of his films — with a man alone, overshadowed by a huge moral question mark. In this case, the question mark is also a narrative one. The final scenes of the movie show a cascade of newsmagazines featuring on their front covers the face of this man alone — the movie’s protagonist, the wannabe stand-up comic Rupert Pupkin. Pupkin, these magazine covers tell us, has finally become a somebody, a celebrity. But are those magazine covers “real,” or are they part of Pupkin’s fantasy?

There is an answer to that question, and we shall come to it, but more interesting for the moment is how starkly this movie’s ending dramatizes a dominant theme in Scorsese’s work. Pupkin is a character who, despite huge odds, obtains what he has long sought, a moment in the spotlight. Unfortunately he has accomplished this by kidnapping a genuine celebrity and refusing to release him until given a spot on the network so he can perform his comedy routine. Pupkin knows he is committing a crime but defiantly assures himself that it is better to be a “king for a night than schmuck for life.” He is expressing in milder form the same imperative that drives the gangsters in Goodfellas, who would rather be “whacked” or imprisoned than remain “content to be a jerk” (Tommy DeVito) or a “sucker” (Henry Hill).

On his own terms, then, Pupkin succeeds. It is a success, however, like the temporary successes of Scorsese’s gangsters, obtained by criminality and loss of conscience. This phenomenon of tainted success — a phenomenon rich in social implication — lies at the heart of Scorsese’s work.

In his breakthrough movie, Mean Streets, Scorsese dramatizes the opposition between virtue and tainted success in the soul of Charlie, the protagonist. Charlie’s moral struggle begins when he is offered a restaurant by his mafioso uncle. It is an item he dearly wants. On other hand he also wants to be a good man. In his voice-over narration at the beginning of the movie — a conversation with himself — Charlie lays out his basic religious beliefs, the beliefs of a Do-It-Yourself Catholic. “You don’t make up for your sins in the Church, you do it in the streets, you do it at home,” he says. “The rest is bullshit and you know it.” There is never any doubt in the movie about the sincerity of Charlie’s spiritual ambitions, despite his involvement in poolroom brawls, despite his uneasy relations with his epileptic lover Theresa, despite episodes in which he rips off a couple of teenagers looking to buy fireworks and tries to beguile an exotic dancer with a job offer in his new restaurant. At one point, Charlie tells Theresa, “Saint Francis of Assisi had it all down. He knew.”

Can he “make up” for the sin of coveting this restaurant, which he is given only because the previous owner — who commits suicide — has failed to generate enough business to pay off his (presumably usurious) loans to Charlie’s uncle? The offer of the restaurant, which functions in this movie as a symbol of tainted success, or at least the possibility of such success, comes with a heavy price. Charlie’s uncle demands that Charlie stop seeing his friends, the wildly irresponsible Johnny Boy and Theresa. “Honorable men go with honorable men,” he says, which clearly rules out Johnny Boy, and also Theresa, who is “sick in the head.” Charlie attempts to compromise. “I’ve got to stay away from you and Johnny,” he tells Theresa. “I don’t want to stop seeing you…Just let me get the restaurant first. Then things are going to be easier.”

Such deviousness is hardly the role of a St. Francis, and it’s no wonder that Johnny Boy, fully aware of Charlie’s desire not to jeopardize his chances of getting the restaurant, calls him a “fucking politician.” In the end, however, Charlie refuses to quit entirely on St. Francis. The fate of the characters is unclear after the movie’s violent ending, but it does seem, in the light of that ending, that Charlie has decisively turned his back on the restaurant. What matters about this movie, however, is not its ending but the way in which it has set the terms of the drama in which all of Scorsese’s characters, who do manage to get their hands on the restaurant, so to speak, will become embroiled.

These characters, for one thing, will not be victims. They will not be spiritual depressives, like the characters of Bergman, or neurotics (Woody Allen) or helpless witnesses to existential futility (Antonioni.) Marie Connelly states the case well in her book, The Films of Martin Scorsese. “Scorsese’s characters are out hustling, making it in a world that still holds out the possibility of fulfillment of hopes and dreams. Unlike other characters, his do not live lives of ‘quiet desperation.’ His characters are shown from the point of view of the swirling vortex of camera movement punctuated by the beat of contemporary rock music drawing us into their lives.”

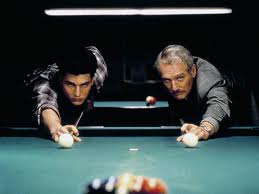

In almost all of Scorsese’s movies there is a scene visually confirming worldly success, or at least affirming its promise, usually in the form of certain objects that are almost transcendent in their materialism, objects that seem to validate his characters’ hustle. The materialistic side of Charlie, for example, is established in a scene showing him lovingly tying his tie, with a brand new shirt, in front of a mirror. The hero of Scorsese’s early feature, Who’s That Knocking on My Door, played by the same actor, Harvey Keitel, also meticulously adjusts his topcoat in a gesture of sartorial satisfaction. A nice car — “That’s the only toy I need,” says its owner — is another symbol of material success in that same movie. Eddie Felsen, the hero of Scorsese’s The Color of Money, his sequel to Robert Rossen’s The Hustler, combines fetishism of cars and fetishism of clothes in a scene where, dressed in an expensive topcoat, he gives his protégé, Vincent, a ride in his Cadillac. “It’s been very good to me,” Felsen says of the liquor business. “I mean, you’re sitting in it and I’m wearing it.” (Viewers of The Hustler will recall that Felsen’s nemesis in that picture, the gambler Bert Gordon, bought himself a fancy new car every year to validate his success.)

“Nice car,” says Vicki, upon being introduced to her future husband Jake La Motta in Raging Bull — what girl doesn’t appreciate a suitor with a hot set of wheels? Scorsese certainly understands this, but between cars and clothes he seems more fascinated by clothing as a status indicator. The progress of Jimmy Doyle, hero of New York, New York, can be charted by the clothes he wears. At the beginning of the movie, Doyle stands amid the cheering throngs in New York celebrating V-J Day (the entire country enjoying its own tainted success as victor in World War II) dressed in two-toned brown and white shoes, white trousers and a Hawaiian shirt — an outfit he won in a card game. “Do I look like a gentleman in this shirt and these pants to you?” he asks the girl he is inelegantly trying to pick up. (The answer is no.) By contrast, at the end of the picture, Doyle is dressed in a natty dark gray suit (complemented by a pair of black shoes) with white shirt and silver tie. Add a topcoat and an umbrella, and the now successful Doyle is positively dapper.

In general, Scorsese’s gangsters are sharply dressed, if not always in the best of taste. One of the scenes establishing Henry Hill’s tainted success in Goodfellas is the shot of his endless bedroom closet full of suits. In Casino, protagonist Arnold Rothstein, manager of a casino for the mob, is perpetually turned out in matching suit, shirt and tie — red on red, white on white, blue on blue, green on green, cream on cream, lilac on lilac, tangerine on tangerine. “Look at you,” a fellow gangster says at one point. “You’re fucking walking around like John Barrymore. A fucking pink robe and a fucking cigarette holder.”

But there are many other material symbols of tainted success in Scorsese. One of the most notable is the championship belt — “a very rare item,” a pawnbroker tells its owner — won by Jake La Motta in Raging Bull. “I got a nice house, I got three great kids, I got a wonderful, beautiful wife — what more can I ask for?” La Motta tells a reporter in his retirement, sitting by his driveway where two convertibles are parked — but it is this championship belt which radiates talismanic power, the power suited to a winner, and when La Motta literally attacks that belt with a hammer, extracting jewels from it, his fall from grace is graphically demonstrated. (The wife and kids, by contrast, simply drop out of the picture.)

In Casino, the magical object signifying worldly success is the house Rothstein shows his new bride, complete with swimming pool and baby grand piano. This house, plus a chinchilla coat and a drawer full of jewelry, marks his marital covenant with her, in lieu of romantic attachments. (His bride frankly admits that she does not love him, but allows that his house is “great.”) Real estate in another form plays a similar role in The Departed, when the corrupt police officer Colin is shown an apartment in Boston with “a great view of the State House,” by a real estate agent. It’s such a desirable apartment, the agent says, “You move in, you’re upper class by Tuesday.” Colin takes it. He is, after all, a success as a member of an “elite unit” of the Massachusetts State Police, acquiring more and more influence within that unit as the movie progresses. The last scene of the movie shows the view of the State House and the parquet floor across which the blood from Colin’s head oozes. It’s Scorsese’s most succinct and vivid demonstration of the price of tainted success.

The signifiers of tainted success in Scorsese are not always, broadly speaking, material. In Taxi Driver, the hero Travis is hustling for a peculiar kind of success. “Listen you fuckers, you screwheads,” Travis proclaims in his empty apartment. “Here’s the man who would not take it anymore…Here’s the man who would not take it anymore. The man who stood up against the scum, cunts, the dogs, the filth, the shit. Here is someone who stood up.” When Travis fulfills this ambition to “stand up” by fatally shooting a pimp — “the worst sucking scum I’ve ever seen,” Travis says — his success is validated not by material objects but by press clippings. TAXI DRIVER BATTLES GANGSTERS reads one admiring headline. TAXI HERO TO RECOVER proclaims another. The same form of validation occurs at the end of New York, New York when Francine’s success is shown by a montage of magazines — bearing such names as Screen Idol, Glitter, Stargazer, Fan Club, Photoplay — featuring her face on the cover. It’s the same technique used at the end of King of Comedy, which is why, I think, the latter display of magazine covers is not simply dreamed up by Pupkin.

This affirmation of tainted success via journalism — and news photography in particular — has no direct connection to filthy lucre, but is just as disgusting in Scorsese’s eyes. In The Aviator, photographers are constantly in Howard Hughes’s face — when he unveils a new airplane, when he crash lands and nearly kills himself, when an outraged girlfriend rams his car. These photographers validate celebrity-hood, and in that sense they validate success, but as Kate Hepburn tells Hughes, they are relentless. “When my brother killed himself, there were photographers at the funeral,” she says. “There’s no decency to it.” At best, photographers and journalists miss the point, as in the case of Travis’s press clippings.

All the more interesting, then, when Scorsese himself becomes a photojournalist of sorts in The Last Waltz, his cinematic tribute to The Band. In this documentary Scorsese displays the same sensibility and the same obsessions — including his interest in tainted success — that he brings to many of his films. The success-establishing scene in this movie, for example, is the shot, early in the film, of the long line-ups of fans waiting to buy tickets to the concert. This shot functions in the same way as shots of Henry Hill’s bedroom closet or press clippings do in other movies. After this introduction, the discovery of a hint of corruption in The Band’s success is not long in coming.

That discovery begins when Scorsese, in his interviews with the members of The Band, elicits a sense of innocence lost. One of the band members, Garth Hudson, evokes an idyllic period, in the early days of The Band’s existence, before their fame, when they all lived in Woodstock, N.Y. “We got to like it, just being able to chop wood or hit your thumb with a hammer,” Hudson recalls. “We would be concerned with fixing the tape recorder and fixing the screen door, you know. Stuff like that. Getting the songs together.”

Then came the years on the road, with ever-growing fame, and a different set of rewards. Scorsese delicately raises the subject of groupies and Band member Richard Manuel displays a roguish, slightly goofy grin. “I love ’em.That’s probably why we’ve been on the road,” he says. He pauses. “Not that I don’t like the music.”

This is reassuring news. We wouldn’t want the music to be forgotten. At the same time we are aware that things have changed since Woodstock days, when music was everything. Hudson still clings to some notion of virtue and the performance of music by recalling old jazz musicians in New York who were “the greatest priests” and healers, but the last word is Scorsese’s, and he chooses to end the movie with a curious tableau of The Band playing the melody to the English Renaissance tune “Greensleeves,” about a prostitute.

Some equivalent of Woodstock days, some authenticity, is the flip side of tainted success in Scorsese. It’s not necessary for a character to have explicit religious concerns, like Charlie in Mean Streets — indeed, explicit spirituality drops off the horizon after Mean Streets. (With the striking exception, of course, of Scorsese’s films about Jesus and the Dalai Lama.) But characters still need to remain in contact with something real, something that is not “bullshit,” in Charlie’s words.

A striking instance is The Color of Money, a movie that would seem to be totally devoted to “bullshit,” in the form of successful hustling, and to the naked materialism of its rewards. “It ain’t about pool,” Felsen tells his protégé. “It ain’t about sex, it ain’t about love, it’s about money.” When Vince takes pity on a sucker, Felsen reads him the riot act. “You never ease off on someone like that,” he says. “Not when there’s money involved.” In pursuit of money, Felsen himself not only sets up hustles but also manipulates Vincent and neglects his own lover. “Do you understand me?” Felsen says to Vince and his girlfriend. “We’re business people.”

It’s a funny business, to be sure. “Money won is twice as sweet as money earned,” is its credo. Under the circumstances it is hard to say which is the purer example of tainted success — the success of the sucker who wins a pool game in the process of being strung along by the loser of that game (the hustler), or the triumph of the hustler who walks away with all the money he can extract from the sucker. Yet this is not the last word, either. Even Felsen, at the end of the day, wants to define himself as a great pool player rather than a great hustler or a great businessman. After he beats Vince at the pool table, in what seems to be a genuine contest between the two men, Felsen is dismayed when Vince subsequently reveals that he “dumped” — that he let Felsen win. Felsen pleads with Vince’s girlfriend near the end of the movie, “I want his best game.” There is no doubt about the sincerity of his plea. It is about pool, after all.

This clinging to a measure of authenticity in a corrupt world can seem senseless, as in Jake La Motta’s taunt to Sugar Ray Robinson after the latter has beaten him to a pulp in the ring — “You never got me down,” proclaims the pulverized La Motta, while an unsettled Sugar Ray stares at him in disbelief — or Arnold Rothstein’s insistence on placing his fate in the hands of his prostitute wife, because, as he says, “When you love someone you’ve got to trust them. There is no other way. You’ve got to give them the key to everything that is yours. Otherwise, what’s the point?” These points of honor do seem senseless — but La Motta must be able to see himself, despite everything, as a man who does not give up or surrender, and Rothstein must be able to see himself as a man who knows the value of trust and lives by it. If they lose this ability, then, as Rothstein says, what is the point?

A man must define himself as something. Scorsese’s Howard Hughes, in the course of unsavory relationships with young girls and involvement in the corruption of military contracts, never loses sight of his self-definition as aviator. That is what he is, and no one can take this away from him. A vague sense of the male imperative of self-definition lies behind the comment made by the hero of Who’s That Knocking On My Door to his girlfriend. “Everyone should like westerns,” he says. This curious statement clearly has something to do with the protagonist’s notion of the western hero. What can that notion be? Robert Warshow articulated it most clearly in a 1949 essay on the western. The western hero, wrote Warshow, in an essay republished in his 1962 collection, The Immediate Experience, “fights not for advantage and not for the right, but to state what he is, and he must live in a world that permits that statement.” Scorsese’s Hughes is a businessman, but he is not really interested in corporate empire building. He is interested in stating what he is, and that thing is not a businessman but an aviator. Scorsese’s Felsen may insist that he is a businessman, but when the pressure builds within him to state what he is, that something is a pool player.

The western hero is also a figure for whom love is notoriously an irrelevance, a reality Scorsese confronts in a number of his movies. “This is the most important thing to me besides you, you understand?” says Jimmy Doyle to his wife Francie, referring to his saxophone. “If I can’t do this, then I’m no good for you and I’m no good for anybody.” (The symbol of his authenticity seems to be the scene in which he uninhibitedly plays this saxophone in a Harlem nightclub.) The equally talented Francie, a singer, seems to have a more relaxed attitude towards her art — it does not define her quite so urgently. Yet New York, New York is one of Scorsese’s most interesting pictures precisely because it does portray a marital union of equals, in which love and self-definition should presumably co-exist. Certainly Francie is never in danger of becoming an irrelevance. When she starts making compromises with her art it undermines her husband’s self-definition. “You got everything, man,” he tells her. “You got it easy and I got nothing.”

In the end both settle for tainted successes. Echoing Charlie’s desire for a restaurant in Mean Streets, and answering his own complaint that he has “nothing,” Doyle becomes owner of a restaurant/night club — a classy joint, but Doyle is no longer the sax player who “blows a barrel full of tenor.” Francie goes Hollywood and stars in a sentimentalized version of her own career and marriage in a movie entitled Happy Endings, which Doyle aptly calls Sappy Endings.

The sluggish and rather forced quality of the movie — whatever spark it possesses comes not from music or sexual tension but from Doyle’s obnoxious qualities, which De Niro, in his fashion, plays all too well — is an indication of how uneasy Scorsese is with romance. Behind romance lies domesticity, and his men are too restless for domesticity, no matter how enticing home and hearth might sometimes appear. Jesus’s yearning for a happy family life with Mary Magdalen is literally The Last Temptation of Christ. He rejects it, of course.

In portraying this search for authenticity via some skill, art, talent or hustle, it is very difficult to escape the male point of view. In Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, Scorsese gives us a female point of view, which is very instructive. His heroine, Alice Hyatt, goes on the road in pursuit of a career as a chanteuse. It’s not a promising pursuit. There is no reason to suppose she is any more talented than Rupert Pupkin, and unlike Pupkin, she is unwilling to enact some desperate gambit in order to succeed. Eventually she gives up and accepts happiness in the arms of David, a solid character. In some remarks on this film, Scorsese has indicated he views the ending as an unfortunate reversion to domesticity on Alice’s part, but few viewers will feel that Alice has made a huge mistake in embracing Kris Kristofferson. It’s not as if she has a promising career up her sleeve. There is no success, tainted or otherwise, for Alice, but not a sappy ending either. It’s just not the kind of ending Scorsese can imagine for his male protagonists.

Why is it so difficult in this world for a man to attain a success untainted by sacrifice of his integrity? For a Catholic like Scorsese, the answer is no mystery — we are fallen beings, in a fallen world. Scorsese’s work dramatizes, more than the work of any other American director, the anguished complaint of St. Paul: “For the good that I would, I do not: but the evil which I would not, that I do.” It may be the case, given lapsed Catholic Scorsese’s own comments about his reprobate status, that he views his own body of work as a tainted success, purchased at the price of his immortal soul.

Certainly Scorsese seems to have lost interest in his earlier theme of redemption, exemplified by movies such as Mean Streets and Raging Bull. Whether the redemption of Jake La Motta is convincing or not, the ending of the movie certainly nudges the reader to drop the Pharisee attitude and look at La Motta’s life through supernatural lens — to see La Motta as the unlikely recipient of grace. Latterly, there seems to be no such attempt on Scorsese’s part. The overtly religious movies he has made — The Last Temptation of Christ and Kundin — may have actually hastened his retreat from the realms of theology because of the failure of either his Christ or his Dalai Lama to emerge as vibrant characters or because of his own failure to overcome the extremely difficult narrative challenges presented by these movies. They call for a degree of sincerity that Scorsese can’t provide — they aren’t his stories and he has only so much leeway to make them his own. How much more excited Scorsese is in dealing with the character of Howard Hughes. There’s a man — an artist demanding perfection at whatever cost, a maverick, a daredevil — close to his own heart. The screen bristles with life and tension every time Hughes appears. But Scorsese can’t redeem him. Hughes demolishes his enemies at a Congressional hearing and proves he is an aviator one last time with the successful flight of the Spruce Goose, but neither of these triumphs wards off the madness waiting to overwhelm him.

His recent concert film Shine A Light, has a dismal effect on the viewer. Scorsese clearly admires the Rolling Stones as a supreme example of hustle, which is why their music is so often heard on the sound track of his movies. But the spark has long since gone out of this particular hustle. Asked recently by an interviewer, “Are you amazed, surprised, delighted that the Stones have lasted this long?” their first manager Andrew Loog Oldham replied, “I wasn’t aware they had lasted this long.” Watching this movie, Oldham would have no grounds for changing his mind. Certainly in this concert movie there is none of the emotional resonance of The Last Waltz, which evokes a complete narrative arc from Woodstock days to the death of the Band. The Rolling Stones never had a Woodstock period of chopping wood and fixing screen doors and writing songs, and it appears they will never bid farewell to public performances while they are physically capable of walking on stage. In the rock solid wall of this dogged careerism and unrelenting appetite for adulation, there is no place for redemption to catch hold. In one of the cleverer moments of the film, Mick Jagger bursts out of a side door to sing “Sympathy for the Devil” with his off-key “woo woos.” Scorsese lights that space behind the door a lurid red, as if Jagger is just emerging from some kind of cheesy inferno. It’s a playful touch, but not entirely a joke to the director whose character Charlie, in Mean Streets, muses on the eternal flames of hell.

An interesting question is whether Scorsese has dropped this theme of redemption because of an intellectual or emotional change in his own makeup, or whether he has dropped it because he has perceived, with his highly sensitive antennae, something increasingly dark in the American landscape.

—Philip Marchand

.

Philip Marchand was born and raised in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and attended the University of Toronto, where he obtained a B.A. and an M.A. in English literature. Afterwards he spent several years as a free lance magazine writer in Canada. A collection of his 1970s journalism was published in 1976 under the title of Just Looking, Thank You: An Amused Observer’s Views of Canadian Lifestyles, by Macmillan of Canada. An unsympathetic critic termed the book the poor man’s Tom Wolfe and he may have been right. The author is not sure he wants you to look it up if you are so inclined.

A more credible book was his 1989 biography entitled Marshall McLuhan: The Medium and the Messenger. A slightly revised edition, with a foreword by the late Neal Postman, was published by MIT Press in 1998. It is still in print for all I know. In a recent article in the New York Review of Books, Pico Iyer called it “delightfully readable.”

Marchand has also written a crime novel, the 1994 Deadly Spirits. Again, the author is not sure he wants you to look it up. It’s okay, but not great.

Finally McClelland & Stewart published Marchand’s Ghost Empire: How the French Almost Conquered North America in 2005. (An American edition was published by Praeger in 2007.) This is a great book and you really should read it. It’s a mixture of travel, memoir and history.

From 1989 to 2008 Marchand was books columnist for the Toronto Star. He currently writes a weekly book review column for the National Post.

He is married and lives in Toronto.

.

.

—Philip Marchand (himself)

It’s always been a dog backyard. Before Nixon we had Chevis and Bianca and Goth, but they all were old and soon would need replacing. Nixon was unlike any of those dogs, however. Where they were calm in their old age (the only ages at which I knew them), Nixon continued to act like a puppy long after he no longer looked like one. And I disliked him for this. His tail hurt when it wagged against your leg and it was always wagging. He bounded through the house if we didn’t confine him to the kitchen and, later, he became a chronic fence jumper. I suppose he had neighborhood gallivanting in his blood—after all, that is how he came to be. And even though I wanted to leave the backyard, to go beyond the fence, I couldn’t understand his need to do so. What did Nixon do out there among the wanderers? Did he mingle with the transients who asked for bus money? Did he run with the children on their way home from school? My parents warned if he did it again after so many times, they would not pick him up from the pound. I envisioned doggy gas chambers and wished he would just stay in the yard.

It’s always been a dog backyard. Before Nixon we had Chevis and Bianca and Goth, but they all were old and soon would need replacing. Nixon was unlike any of those dogs, however. Where they were calm in their old age (the only ages at which I knew them), Nixon continued to act like a puppy long after he no longer looked like one. And I disliked him for this. His tail hurt when it wagged against your leg and it was always wagging. He bounded through the house if we didn’t confine him to the kitchen and, later, he became a chronic fence jumper. I suppose he had neighborhood gallivanting in his blood—after all, that is how he came to be. And even though I wanted to leave the backyard, to go beyond the fence, I couldn’t understand his need to do so. What did Nixon do out there among the wanderers? Did he mingle with the transients who asked for bus money? Did he run with the children on their way home from school? My parents warned if he did it again after so many times, they would not pick him up from the pound. I envisioned doggy gas chambers and wished he would just stay in the yard.

KLM: Most rules don’t make sense in writing fiction. If someone tells me a rule to follow, it just goads me into trying to break it. So I disagree that a story has to contain a change by which the character is forever changed in order for the story to be effective. The reader has to feel the possibility of change.

KLM: Most rules don’t make sense in writing fiction. If someone tells me a rule to follow, it just goads me into trying to break it. So I disagree that a story has to contain a change by which the character is forever changed in order for the story to be effective. The reader has to feel the possibility of change.