William S. Burroughs & James Grauerholz in Lawrence, Kansas

William S. Burroughs & James Grauerholz in Lawrence, Kansas

/

When I was in grade school, William S. Burroughs visited my house. At least I think so. Strange old men with secrets were fairly commonplace in Lawrence, Kansas. Old Man Puckett, our octogenarian next door neighbor on Delaware Street, lived alone in squalor for all the time we knew him, until he was robbed and murdered in his home. The men who killed him found little of value, but it was obvious they were looking for something. After the crime, police searched his house extensively, and after removing the floorboards they found just shy of $100,000 hidden. Old Man Puckett came to our door once trying to get us to sign some sort of petition. When he tried to come in the door without my parents’ permission, my bulldog just about ripped his arm off. My mother brought him in and wrapped his arm in gauze, but he refused to go to the hospital.

Old Man Burroughs was better prepared when he came knocking. When mother opened the door and my bulldog growled, he simply waved his cane at her and she slunk back away from him. He spoke slowly and lucidly to my mother, accusing me of trespassing on his property and chasing his cats. This was probably true – I chased every cat I saw, and so did my bulldog. My father glowered in the corner, but didn’t open his mouth.

Old Man Burroughs didn’t say a word directly to me until he’d laid out his case to my parents. He then looked directly into me. “You should know,” he said, “that I’m quite proficient with a handgun.”

Burroughs and I came into Lawrence from opposite ends. He was at the end of a life lived fuller than most, and I was just beginning mine. Both of us were bewildered. He arrived in 1981, when I was eight years old. He seems to have spent most of the eighties fluctuating between the peace of an old warrior retiring to his cottage and deep depression. His friends had left him and the anti-establishment movement he’d helped found had been co-opted by the establishment. He grudgingly accepted his induction into the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters in 1983, and went home broke. He tried to get Ginsberg, Gysin, Giorno, and the rest of them to come visit him, but they mostly scoffed, referring to his new home in Kansas as Nowheresville.

For the life lived outside the communal graces of religion, family, and conventional sexuality, he was now paying in loneliness. His closest friends were the brood of cats he gathered around his house on Learnard Street. By 1987 he’d finished The Western Lands, the final volume of his Red Night trilogy, in which he supposedly gathered the loose ends of his previous work into a cohesive mythology. I haven’t read the trilogy. I have, however, read The Cat Inside, a brief and surprisingly tender volume he published in 1986 about his beloved brood. In one passage he recounts a series of dreams he has about Ruski and Fletch, his first cats, in which their heads are on the bodies of children. He doesn’t know how to take care of children but he vows to protect them, saying, “It is the function of the guardian to protect hybrids and mutants in the vulnerable stage of infancy.” I’m now very sorry if I tormented his cats.

When I left home at 17, I discovered William S. Burroughs – the writer, not the old man. It wasn’t until I heard a recording of him reading that I made the connection between the two. I read Naked Lunch three times, desperately trying to make heads or tails of it. Like most other male college English majors, I became obsessed with the Beats. But mostly, I loved, still love, the voice of William Burroughs. It was at once weathered and sarcastic, two attributes I assumed of myself way too early. But that’s what it was – William S. Burroughs was who I wanted to be, the literary tradition I wanted to come from, and I’ll even say it – the father I wished I had. His death in August of 1997, just a couple short months after Ginsburg’s, officially ended the Beat Generation, though it had long been usurped and bowdlerized by its own legend. I eventually wrote my graduate thesis on the influence of Naked Lunch on film and popular culture, but I wanted much more than that to write about the influence of William S. Burroughs on me.

Burroughs had a son of his own, Billy Burroughs. I’m continually surprised at how few people know this – or even believe it – when I mention it. But it’s easy to understand why, really. Not even taking into account his homosexuality, Burroughs just doesn’t seem like father material. He had, after all, shot the boy’s mother. And he in fact wasn’t much of a father to Billy, mostly allowing his own parents to raise him. Billy went to stay with his father in Tangiers where, according to an article Billy wrote for Esquire, Burroughs allowed at least one of his friends to molest his son. Billy wrote that article shortly before he died at age 33, saying that his father had poisoned his life. He did, though, read and reread his father’s books – I imagine this was a way to feel close to his shadow-father – and cherished every scrap of affection his father threw him, like the Rimbaud copy mailed to him when he reached puberty, the glass-cased Amazonian butterflies , and the shrunken heads mailed from Africa. Billy also wrote two novels. While his father was recovering from his heroin addiction, Billy became an alcoholic of the most extreme sort, vomiting blood while having dinner with Ginsberg, needing an experimental liver transplant, and eventually dying alone in a ditch in Florida. William Burroughs was in New York when Ginsberg called and told him. That was 1981, the year Burroughs moved to Lawrence. Burroughs fell back into methadone and/or heroin use around that time, and was addicted for the rest of his life.

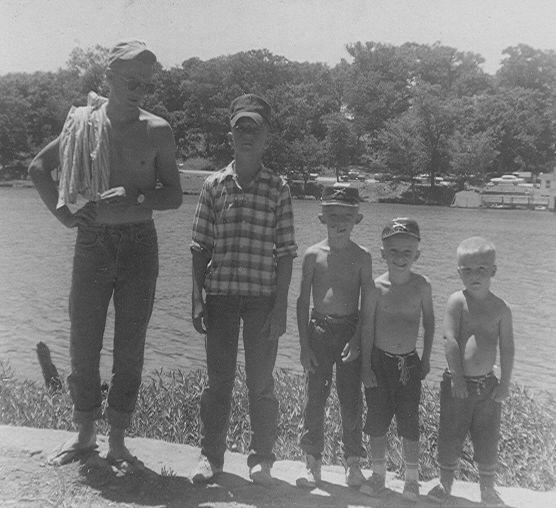

My Grandpa Light, my mother’s father, died in 1997, a few months before Burroughs. I loved him, but I didn’t cry at his funeral the way I cried in my apartment that August. My Grandpa Proctor, my adoptive father’s father, died just last October. He’d had lung cancer for about a year. I hadn’t gone back to see him because he wanted me to reconcile with his son, whom I’d chosen not to see since my mother divorced him. When I said I couldn’t Grandpa Proctor disowned me, via email. But I went back to Kansas when he was pissing blood and treatments were stopped. I didn’t know if he’d let me in when I showed up on his doorstep. But he did. He was old, and broken, and wanted to talk. So we talked – about his job as the first union projector operator at the theater downtown, and how all his sons got smallpox the same summer when they lived on 19th Street and they had to quarantine the house and have the rest of the family stay out at the shack on Lone Star Lake. I remembered that shack – we used to spend our summers there when I was in early grade school. It was only about half the size of the loft apartment my wife and I were sharing when my grandpa got cancer, but somehow my grandparents fit all three of their sons, parents, siblings, and their families into it. I asked him what happened to that old place.

At Lone Star Lake – my grandpa (far left), adoptive father (middle), and uncles (photo courtesy of my Aunt Carol)

At Lone Star Lake – my grandpa (far left), adoptive father (middle), and uncles (photo courtesy of my Aunt Carol)

“Oh, we sold that place sometime round ‘85, to some old artist type, name of Burroughs. You probably heard of him.” He then told me how this artist type didn’t even do much out there after he bought it, just rowed out to the middle of the lake and sat all day. “And get this,” Grandpa told me, “I sold it to him for under $30,000. Now just two years ago the owners sold it for $160,000 to some guy in England, just because that old Burroughs lived there.” I didn’t believe him when he told me, but I googled it and found the eBay listing. I even found a journal entry from Burroughs himself about our shack:

I got me this cabin out on the lake. Got it cheap since I was able to put up cash, which the owners needed to put down on another house they is buying out in the country. Could easy sell it now, but what for? A few thousand profit? Nowadays what can you do with that kinda money? My neighbor tells me right in front of my dock (I’ve got access, and that is the thing matters here on the lake… a dock, see!), well, my neighbor tells me that right in front of my dock is the best catfish fishing in the lake, but I don’t want to catch a catfish…I could cope with a bass, or better, some bluegills — half pound, as tasty fish as a man can eat — fresh from the lake, and I got me an aluminum flat bottom boat, ten foot long, $270…a real bargain. I likes to row out in the middle of the lake and just let the boat drift…

So there it is. Burroughs spent the last years of his life in the middle of the lake of my youth. I won’t even venture a guess as to what he thought about out there, but I do know that less than a month before he died in 1997 he wrote in his journal:

Mother, Dad, Mort, Billy – I failed them all –

And I don’t know what conclusions to draw from that, what lesson there is to be learned, what connections there are to make. I’m now 36 years old, three years older than Billy Burroughs was when the weight of his father’s legacy ravaged his liver and landed him in a ditch in Florida, but less than half as old as William Burroughs was when he exited the world addicted, without a family, and adrift alone in the middle of a lake so muddy my wife refuses to set foot in it. I have a daughter now, who will be a year old in just a couple of weeks. Somehow I’m glad she’s not a son.

Burroughs, rowing in Lone Star Lake

Burroughs, rowing in Lone Star Lake

— John Proctor

,

.

.

.

Great post! A unique piece of American literary history! Thanks for posting the photos, John.

John, this is a great little piece of writing, and fascinating!

Great stuff, John, and a compelling read. I especially like the introduction, the way it set up what follows.

“sets” up — sorry

Gary, I’m not sure I can take your comment seriously with such an egregious lapse in verb tense. 😉

Seriously though, thanks. I did this piece “on assignment” from Doug, as he’d been listening to me relay stories of Burroughs ad nauseum for the past couple of months until he finally politely asked me last week to just write it down.

It was an error of agreement — but I just don’t see stuff in the little comment box so hot.

But it really is good material and there’s plenty to come back to. How many of us have something similar? The intro sets up all kinds of stuff to mine.

Thanks for the eloquent and sad post.

How delightful! Thanks for sharing this with Burroughs fans, and well-written.too. I hope there’ll be other stories of his life in the Lawrence years

to surface. Always wondered what he found to do with his time in Kansas.

(I lived there for a decade one winter.)

I’ve often thought that Billy’s choice of alcohol must have mortified him: it’s

Such a sloppy,heavy-handed high. Before Billy became a hopeless drunk.he

was a speed freak for a while,probably in imitation of his mother. Neither

high was conducive to long life or considered thought,and baffled the hell

out of Bill sr. Probably enough reason to make both appealing, but just another thing that made father and son such a mystery to one another….

Thanks again,and best wishes ,

Michele

Does anyone know where I could read the Esquire article written by Billy Burroughs? Online, if it’s available? If not, the issue of the magazine would help…

I’m reading “Cursed at Birth” presently, and it might be the most revealing document of addiction I’ve seen so far, what with all the self-deception, delusions of greatness, terrible attempts at humor and so on. It doesn’t get any better, he doesn’t.

Matti, I’ll try to find it for you – it’s been awhile since I used it. I will say that I initially heard about the Esquire piece in Literary Outlaw, Ted Morgan’s colossal biography of Burroughs.

Thanks! That information does help. Sr has never interested me much.