Dear Nick and Chris:

Fuzz from the poplar sticks to the windshield of our Ford. In the courtyard of our building, the birch bursts with pollen and I sneeze when hanging out sheets to dry on our balcony. The sky glows, the days lengthen, you both grow long and lean. A strange time, perhaps, to write you about Christmas, but your father’s gone, and writing this to you fills the hole he’s left.

You’re at an age where you’re interested. You’ve asked how a twenty-year-old man from Siena and a nineteen-year-old art history student from New York met. As an answer I’m writing you about the Christmas of 1977, the first Christmas the two spent together. A bizarre Christmas, with the young woman shut in a monastery—not unlike poor Pia de’ Tolomei in TheDivine Comedy (whom I’ll tell you about later)—while the young man came and went when curfew lifted. In a strange way that Christmas echoes the challenges facing us this spring. We’re here, stuck in Milan, going to school. Your father’s off to Egypt, making a living, returning on short monthly visits.

But you were both born in an advanced age. So before you read about Christmas consider:

In 1977, Siena was a different place from the one you find now. Thirty-odd years ago, no exhaust-belching tour busses clogged the narrow roads. No umbrella-toting guides led tourists up steep Medieval streets. No greasy clouds of McDonald’s fried air hovered in narrow passageways. Back in those days vegetables and fish were sold in the Piazza del Campo. Souvenir shops were few. Iran hadn’t happened. Frost still hobbled relations with Russia. The Red Brigades had assassinated several public figures but were still plotting the murder of Italian Prime Minister Aldo

Thirty-odd years ago, no exhaust-belching tour busses clogged the narrow roads. No umbrella-toting guides led tourists up steep Medieval streets. No greasy clouds of McDonald’s fried air hovered in narrow passageways. Back in those days vegetables and fish were sold in the Piazza del Campo. Souvenir shops were few. Iran hadn’t happened. Frost still hobbled relations with Russia. The Red Brigades had assassinated several public figures but were still plotting the murder of Italian Prime Minister Aldo  Moro. In the Siena of that time, Americans were considered an exotic breed from a futuristic, hedonistic place. In that place your mother, me—one of the supposedly advanced, wanton Americans— in 1977 met an Italian on a cobblestoned street near a Renaissance fortress and found that love in a foreign language and culture is anything but easy.

Moro. In the Siena of that time, Americans were considered an exotic breed from a futuristic, hedonistic place. In that place your mother, me—one of the supposedly advanced, wanton Americans— in 1977 met an Italian on a cobblestoned street near a Renaissance fortress and found that love in a foreign language and culture is anything but easy.

The girl you’ll find in the following collage seems very young, her choice of fancy words an effort to hide a naïveté that today seems antiquated but then was typical of her age and her background. You might find it hard to believe she’s your mother, just a couple years older than you are now.

Reading, reminiscing, reflecting on how conflict was resolved. That’s why history matters. But you know that. Your teachers at school have already told you.

I’m enclosing sixteen excerpts from a journal and class assignments together with old snapshots and this letter:

1. The semester is over! Three months have flown by. Segments of time have been consumed yet the waxing moon grows whole again.

Christmas is almost here. Classmates are packing their bags, getting ready to go home and back to their previous lives across the ocean. I’ll miss Elisabeth and Brian, but gloat when considering Rachel’s departure. No more competition from her re: Mauro. I long to say, “I’m staying…you’re going,” but curb the urge. The semester has flown by with an alacrity that’s impossible to comprehend. At the end of the next short term, I will be in her position.

2. During the Christmas holidays, while the Ticci family (my hosts when school’s in session) suns on the beaches of Sicily, I’ll retire to a monastery and embark on a trip to the 13th century and the contemplative life. On Thursday I’ll be locked away behind big iron gates.

The monastic solution to the holidays was Mauro’s idea and I agreed because it’s quite economical to rent a monk’s cell—information my guidebooks neglected to tell me. So while the Ticcis are gone, I’ll pay a pittance to stay at Monastero Ventoso, on the outskirts of Siena.

The Padre Superiore has given me a room by the main entrance. Reserved for stray visitors, it boasts two twin beds—iron bedsteads with old-fashioned mattresses stuffed with wool—a night table with an iron lamp, a high window, a crucifix, a cherry wardrobe, a small desk. A print of the Madonna hangs over the desk.

Don’t get the wrong idea. The Padre has no hotel business on the side. When we met he stressed his convent is a place of prayer and meditation. He said I mustn’t be a disruptive influence. I promised not to disrupt anything. But permission was granted only when Mauro’s parents, well-known members of the parish, vouched for me. I was surprised they went to such lengths considering their feelings for me, the son-stealing American; Mauro said it was nothing, his father made a short phone call.

The Padre will stretch curfew past the usual hour of 8:00 p.m. to allow me to eat dinner elsewhere. At 10:00 p.m. sharp the gates will be locked. If I’m late, I’m out. The gate will be unlocked again at 7 a.m.

Honor and virtue; silence, solitude and prayers; curfews and gates heavily clanging shut. These are the themes I have confronted so far in arranging my new lodgings. Fierce and monumental. Worthy of the Middle Ages. Worthy of Pia de’ Tolomei, the 13th century Sienese noblewoman who perished while locked up in her husband’s castle.

2. Dressed up in Christmas finery, Siena bewitches. In Via Montanini two hundred Christmas trees flaunt their red ribbons. The Banchi di Sopra glitters with garlands of green fir and gold pine cones. The Via di Città leading up to the Duomo shimmers with candles and blinking lights. Under these gaudy displays, shop windows—lavishly arrayed in seasonal glitter—beckon. They persuade wallets into emptying their contents for last-minute purchases. I spent too much on gifts for Mauro’s family and now have to wire Mom for more cash.

3. I transferred my belongings from the Ticci’s to the monastery with Mauro’s help. Then it was on to Mauro’s home for lunch. I brought his mother a bunch of exuberant pink lilies that had been steamed open in a greenhouse in the hills behind San Remo.

His family, unlike the lilies, acted formal and stiff. Mauro’s mother took the flowers and smiled, but only with the bottom half of her face. His father, after a quick “bon giorno,” disappeared into the far reaches of their home. His grandmother, a small wrinkled lady, frowned when I tried to shake her hand, disapproving of my presence at lunch. Mauro said afterward that back in her day, women needed an engagement ring on their finger before they could meet a young man’s family.

At the table we made conversation:

“So, Mauro, your friend isn’t going home for Christmas?” his mother asked in rapid Italian, figuring I wouldn’t understand.

“I have another semester to go and the fare’s expensive.” I said, answering for myself.

I could have told her I’d had an invitation to go Paris to visit an uncle—expenses paid by the uncle—but decided to stay in Siena because of her son. Instead, I decided not to fan the flames of her dislike and said nothing.

When wine had melted some of the frost in the atmosphere, between the two meat courses of fagiano and cinghiale (pheasant and wild boar that the head of the family had shot), Mauro’s father told me of his hobby. He opened his weapons cabinet behind the dining room table and showed me his hunting rifles, bullets and knives. Then he took me down the hall to see his boar’s head wall trophy.

Hunting, blood-letting—his favorite past-time. His eyes shone when he told me he especially enjoys hunting wild boar. The dogs, the chase, the kill.

4. It’s lonely in this monastery. And cold. Since curfew I’ve shivered in this bed with the lumpy mattress and thin blankets, reading melancholy stories of Pia de’ Tolomei, the noblewoman Dante relegated to Purgatory in the Divine Comedy. Apparently accused of infidelity and confined to a remote spot in the swamplands of Maremma by her husband, she languished and died there almost 700 years ago.

Like Pia I don’t see anyone, I don’t hear anyone. The monks live in a different section; I’m exiled to the wing near the head office where matters such as interviews with female boarders are conducted.

Tonight the howling of the wind keeps me company.

At least Pia had a maid.

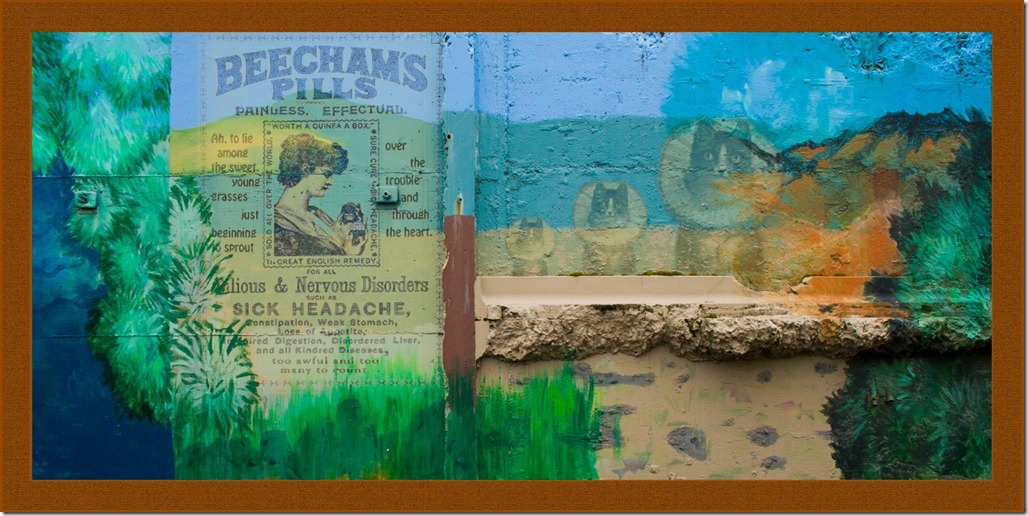

La Pia de’ Tolomei, by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

5. On tiptoes, in my flannel nightgown with the lace around the neck, I peer out the tiny window over my bed.

The wind has ceased moaning and groaning and whipping past corners. No lone moto, no car, no pedestrian sputters or clips through the night. No one but me sees that the heavens glow with a majestic full moon that dispels, with its brilliance, the shadows of the sleeping town waiting for Christmas to arrive.

Cypress trees block much of my view but I imagine Siena quietly spread over the hills south of me. Close by are several brick high-rises built in the 60’s. Far off, toward the centro storico stand the black-and-white-striped bell-tower at the Duomo, the brick-and-marble Torre del Mangia in the Piazza del Campo, and the red bell-tower at San Domenico. Three far-off friends.

As I sink down to the mattress I wonder. How many Christmases did Pia linger at her solitary window before she succumbed to loneliness?

This monastery. Pia’s story. Mauro’s hostile parents. They’re casting a pall on the joy of this season.

Snow at the Duomo

6. Today, Christmas, Mauro gave me a small gold ring with a red stone and a card with a sonnet by Pascoli in impossible Italian. Then he said we were fidanzati but that we wouldn’t mention it to anyone right now. They wouldn’t understand. I agreed, but wished he’d stand up to his parents and tell them how he feels about me instead of keeping it a secret.

I gave Mauro a glossy book of New York City with photographs taken by famous photographers of the last twenty years.

He’s never been out of Italy.

He flipped through the photos not speaking. Then he slapped the book shut, coughed and squeezed my hand and said he’d like to visit me in New York some day.

I coughed too and retied the lace on my boot so he couldn’t see my face.

I don’t want to think about leaving. I don’t want to think about impossible visits in New York some day.

When I bought the book, it seemed perfect. Now I wish I’d given him something else.

7. Mauro and I went to visit the Palazzo de’ Tolomei this morning and study it. I’m writing an essay over the holidays for Italian culture class.

Affixed to the side of the austere building hung a small plaque, high up, engraved with two somber, melancholy lines from Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy:

Ricorditi di me, che son la Pia:

Siena mi fè; disfecemi Maremma:

Purg. V 133-134

(Remember me who am La Pia; me

Siena, me Maremma, made, unmade….

translation by Dante Gabriel Rossetti)

I’d admired the Tolomei Palace innumerable times, but the building had seemed just another beautiful remnant of Siena’s illustrious past. Now that I’d been reading about one of its inhabitants, it had acquired significance. As I stared up at the diamond-paned windows on the piano nobile with Pia’s sad words echoing round the piazza, I wondered. Pia had been “made” here. She’d been born and grew up within this edifice’s aristocratic walls. Once she had looked out over the square where I was standing. But how and why she’d been “unmade” in Maremma was a mystery that had attracted attention throughout the centuries and would likely never be solved.

In addition to the two lines reproduced on the plaque, Dante writes just two more lines about Pia. In them he alludes to who is responsible for her death: her husband, Nello Pannocchieschi.

salsi colui che ‘nnanellata pria

disposando m’avea con la sua gemma

Purg. V 135-136

(…This in his inmost heart well knoweth

he With whose fair jewel I was ringed and wed ….)

But Dante doesn’t explain why or how Pia dies and what Nello’s role is. No late 13th-century historical records to clear the matter. For centuries scholars have disagreed as to the nature of Pia’s sins. That Dante considered her a sinner up until the very last minute when she repented (but without receiving last rites) thereby saving herself from hell and the Inferno is clear, otherwise she wouldn’t be in Purgatorio. But was she an adulteress? Or was she guilty of some other crime? And was she thrown from a window in a castle in Maremma on Nello’s orders, who some say wanted to marry someone else? Or did she die of illness and solitude?

When I asked his opinion Mauro said he thought she’d cheated, gotten caught, said she was sorry but her husband rightly turned a deaf ear. Instead, I preferred the line of reasoning of one of the most popular legends. According to this version of events, Pia’s husband shut her up in his castle in Maremma because an associate—whose advances Pia had rejected—told Nello she’d been unfaithful but gave false evidence to back the charge. Locked away in swampy, mosquito-ridden Maremma marshlands, Pia got sick with malaria. In the meantime, Nello discovered the lie, returned to release her but instead arrived in time for her funeral.

“I don’t want to finish in the same way,” I said after giving Mauro my opinion. “Expiring on the outskirts of Siena.”

“I knew this Pia trip was going to end up back at the monastery,” he said, frowning. “I thought I was doing you a favor keeping you safe at night.”

Safe at night? Since when was safety in Siena an issue? And then I understood. He didn’t trust me.

“It’s not you I don’t trust,” he said when I asked. “It’s the men here. This is Italy. You’re American.”

I’m a twentieth-century Pia. And Mauro? He’s a twentieth-century Nello Pannocchieschi.

8. I spent the early morning writing in my cell. My neck was stiff after a bad night in the bumpy bed.

At ten thirty weak sunshine and a watery blue sky beckoned. I put down my pen, stretched, grabbed my coat and began a tour of the gardens.

To one side of the main building stood leafless trees, un-pruned hydrangea bushes replete with last summer’s flowers (though now brown and stiff), a potted lemon tree swathed in plastic to keep it warm on cold nights. I picked a dried rosebud from another bush in need of care.

“Signorina, what are you doing?” asked a voice from behind. I turned. It was the Padre. He frowned at the dead flower in my hand.“This area is off limits. Didn’t I tell you this already? You must stay along the gravel drive to the front gate.”

“But what’s wrong with a little walk? I’ll be quiet.”

“The brothers are in the vegetable garden. You must not disturb them. And please don’t pick anything else.”

“But, it’s dead,” I said.

“It’s not your place to say or to pick,” he said.

Pia de’ Tolomei, by Stefano Ussi

9. Signora Rossi makes wonderful meals every time I’ve been invited.

“I’m sorry if she feels obligated to extra fuss,” I said to Mauro.

“No,” he said. “She can’t help it. It’s her way when we have company.”

Today’s lunch menu consisted of the following:

crostini misti (paté and prosciutto hors d’oeuvres)

gnocchi alla romana (au gratin dumplings made of semolina wheat),

coniglio e gobbi fritti (fried rabbit and gobbi—a celery-look-alike from the artichoke family),

crostata all’albicocca (homemade apricot jelly tart),

panforte, panettone and pandoro (Christmas cakes),

ricciarelli and cavallucci (Christmas cookies),

espresso caffé,

cognac.

“I always cook like this, doesn’t everybody?” she replied when I complimented her skill and generosity and trouble on my account.

“No!” I said, belching softly into my napkin and unbuttoning the top of my skirt.

Soon after, Mauro and I fell asleep sitting up on the living room sofa. His grandmother found us. She jabbed me in the ribs with her finger and hissed something I didn’t understand at Mauro.

Then she yelled. “Get up!”

His mother came running in.

“What is going on in here! What are you doing?”

10. We are going to Pisa tomorrow for the day. Mauro will come and pick me up at 5 a.m.; the Padre Superiore will open the gates early so that I can get out in time to catch the train.

Such magnanimity in bending the rules! Perhaps he is glad to be freed of my presence for the entire day.

I, too, am happy to be leaving the claustrophobic atmosphere at Monastero Ventoso and the glacial stares of Mauro’s possessive family.

I don’t know how much more of this medieval nightmare I can take.

11. I’m in disgrace. The Padre Superiore called me into the office where he first interviewed me. A blond hair has been found in the spare twin bed in my room. Between the sheets. The sheets, in addition, were wrinkled. Clear evidence that someone has been sleeping in that bed.

“Was it Mauro?” he wanted to know. “Someone else?”

I denied any and all knowledge of any blond-haired persons sleeping in the spare twin.

“By the way,” I wanted to ask when the interrogation wound down, “what were you doing snooping?”

12. The Padre Superiore hauled me in again today for more questioning.

“Signorina,” he began, clearing his throat. “Have you thought about our talk yesterday?”

“Yes, of course I have.”

“Well?”

“How can you be sure there is no explanation other than I’m guilty of some crime? What if someone else used that bed before I got to the monastery?” I thought of Pia and false accusations.

“If you change your mind, please come to see me.” He said, staring at his fingernails.

“Don’t you think you should consider that there may be another explanation?” I said, thinking of Pia and her untold version of events, how she hadn’t been able to defend herself, how defenselessness had caused her demise.

But the Padre answered me with a chilling, “How long did you say you were staying here? Was it until the 10th, after the Epiphany?”

“At the very longest. I may be leaving even sooner, if I can make alternative arrangements.” I bluffed, wondering where I’ll go if he kicks me out.

13. Mauro tried to have curfew extended last night so we could celebrate New Year’s together but the Padre Superiore refused. He intended it as punishment, and perhaps as a moment for me to reflect, repent, recant.

I went to bed at 11 p.m. after drinking a Campari soda I had smuggled in. I felt very sorry for myself.

I should walk out, but after paying rent here and buying Christmas presents, I have no money left for a hotel. Mom’s cable hasn’t yet arrived.

14. “What to do about the monastery?” I asked Mauro as we walked in circles around the Castello di Belcaro, an exquisite spot outside Siena where tradition has it nobles once holed up to escape outbursts of the plague.

“What did he say exactly?”

“He said there was a short blond hair in the spare bed.”

“Mine.” Mauro swallowed. “Who do you suppose inspected the linen?”

“I don’t know.”

“Maybe things will die down.”

“He’s a bloodhound, after a scent. He’s not going to give up.”

“Funny isn’t it? ” said Mauro.

“Ridiculous.”

“You were late,” Mauro said, tugging at my hand, “it was your fault.”

I hadn’t woken up in time to catch the early train to Pisa and was not waiting by the front gate like we had arranged.

“But you were the one who breached the walls,” I said. He’d come to my room and had thrown rocks at my window—a misdemeanor. Then, when I opened it, he’d climbed in—a more serious offense. While I finished drying my hair, he’d sat on the twin bed—definitely a felony. And then the rumpling began. A crime of such gigantic proportions that if brought to the Padre’s attention he would lock us up and throw the key into the murky depths of the goldfish pond out back.

“Try telling him all we did was cuddle for a minute before running for the later train. He’d never believe it.”

“You’re right, as a matter of fact, I almost don’t believe it,” agreed Mauro.

15. Entering the Padre Superiore’s study, I found him writing at his desk.

Sinking back in his chair, he studied me. “You have something to say?” he asked.

“I’ll be leaving tomorrow, on the 6th, four days earlier than planned,” I said. “I wonder if I could have a refund on my rent? I’m broke.”

“You want a refund. I’d be glad to give you a refund. But first, is there nothing else? Isn’t something weighing you down?”

“No. I have nothing to say except that I’ll never forget my stay here.”

“It will be hard for us to forget you, as well.” He took his glasses off and put them on the desk. “We had you stay here as a favor to the Rossi family. I’m considering telling them what has happened. What will they think?”

I bit my lip. I wanted my money back. But on the other hand, I didn’t need it back that badly. Mauro said he’d help me out until my funds from home arrived.

“You’d be too late,” I said. “Mauro has already told them. Signor Rossi found it distasteful that someone scrutinized my sheets. But we all had a good laugh. He knows we didn’t do anything wrong.”

Later I told Mauro. We were sitting in his white sedan in a dusky lane near an abandoned school with shattered windows and a missing door where nuns once taught. Rumor has it they abandoned their newborn babies in the woods beyond.

“It was a stroke of brilliance to tell him you’d already ‘confessed’ to your parents, don’t you think? But, suppose I exaggerated too much? And he wants to tell your parents his side of the story?”

“He won’t. His best course is to keep a low profile. And then, even if he does talk to my father, what is the worst that can happen?”

“Your parents will be sorry that they went out of their way.”

“No, they won’t because they know I was home every night.”

“Vindicated only because you have an alibi. Not because anyone believes me.”

“By tomorrow at this time, the monastery will be a closed chapter. It was a bad choice. But it’s almost over.”

“Thank god,” I said, exhaling.

“You know, I’ve been thinking.” He leaned across the seat and brushed my bangs out of my eyes.

I waited for a while and then he told me. He wants his parents to know how he feels about me. That this affair isn’t some boyish infatuation.

I wondered about his change of heart. Had Pia and her unspoken thoughts and words affected him? Had the mystery of her life and death—one without truth and trust—swayed him? Had the monastery showed him that he should speak up?

Somehow—although he didn’t say—I figured this were so.

16. It’s a holiday, the Epiphany, and here’s mine:

Skip living in Medieval establishments such as castles and monasteries.

Pia died a lonely death in one, I was embarrassed and humiliated in one.

No wonder the guidebooks don’t recommend them.

Albergo Castellini—a modest two-star—will do. Mauro’s lending me the money. I’ll pay him back when Mom’s cable comes through.

He says not to worry. He doesn’t want the money. He says he’s hoping to see me smiling again.

Right now I’m waiting by the front gate at Monastero Ventoso. It’s 8:25 a.m. and he’s late, but only by 25 minutes. He’ll be along soon, as soon as he’s through telling his parents.

Boys, your father came along right before lunch. He took me to his parents’. We had a multi-course meal—your grandmother’s way of expressing emotion—and then another, after that. And then many more.

Since then we’ve faced difficult challenges—we’ve done some climbing so to speak. Most of our climbs have been without guides. The air’s been thin, the water’s been scarce, the sun’s been hot, we twisted our ankles, skinned our knees and once ended up badly dehydrated, but somehow we’ve always reached a scrap of shade.

We’re climbing again, all four of us. Your father’s on one side of the Mediterranean. We’re stuck on the other.

But we’ll make it. We can say we love each other.

Your father texted me a minute ago. Here’s what he’s typed in this new, poetic language he’s learning:

“Sabah Al Khair Habibti.”

It means ‘good morning, my beloved.’

After thirty-odd springs together, I think ‘good morning, my beloved’ sounds incredibly fine.

–Love, Mom

–by Natalia Sarkissian