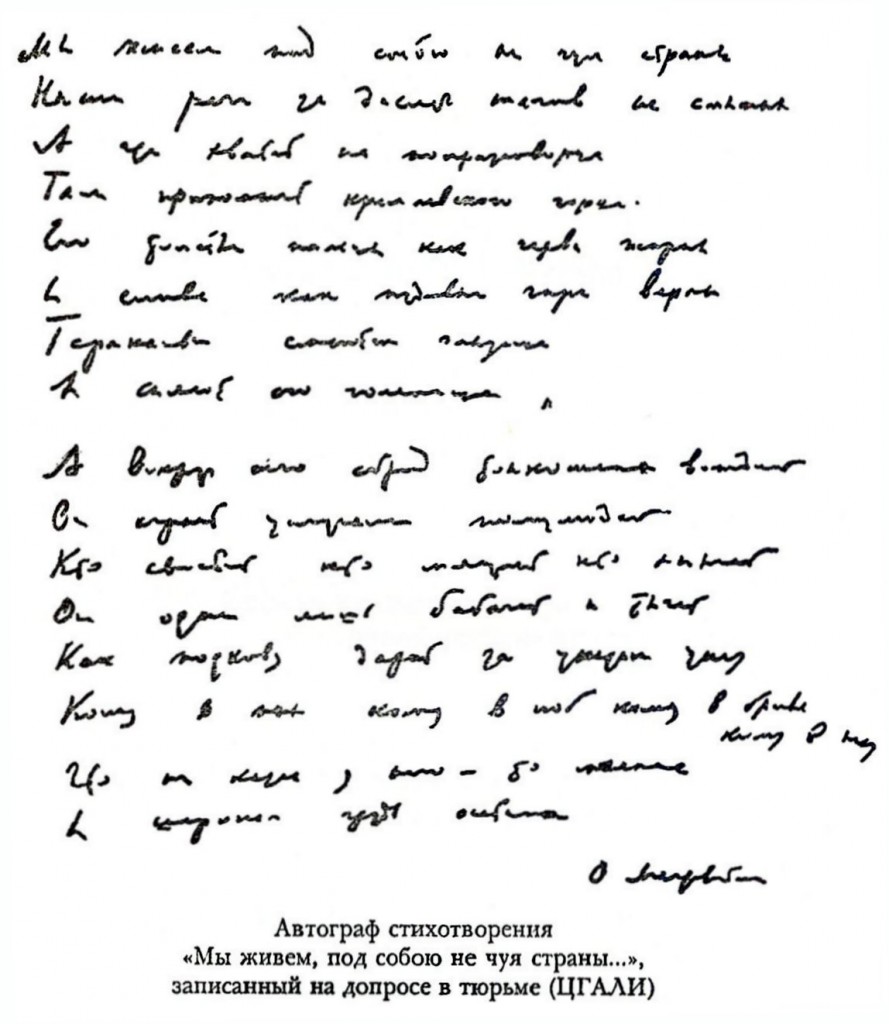

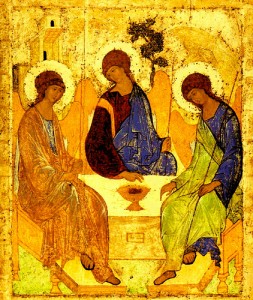

A copy of “The Stalin Epigram” handwritten by Osip Mandelstam.

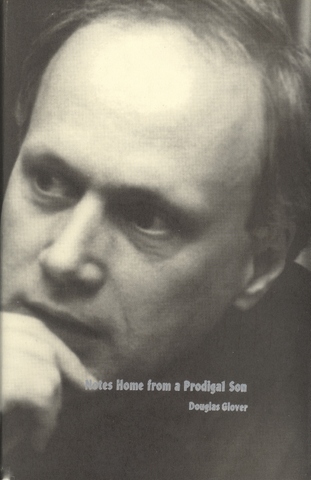

As a young man, Russell Working came out of nowhere to win the Iowa Short Fiction Award for his book Resurrectionists. Then, instead of prudently finding a college creative writing job, he abruptly and romantically packed up and moved to a freezing flat in Vladivostok in the Far East of Russia where he found love and Osip Mandelstam. In this truly masterful essay, memoir laced with love and a passion for art and artists, Russell tells the story of Mandelstam’s fatal defiance during Stalin’s purges and his last days in gulag camp on the outskirts of Russell’s adopted home. I don’t know. I hate the word underrated, but Russell Working really is one of the most underrated writers in America. This essay shows him at his nonfiction best: charming, romantic, his heart full of great writers and his head committed to uncovering the truth, the facts.

dg

.

1. Pictures in a Bookcase

The tenth-floor hallway was filthy: paint was peeling from the walls, the garbage chute stank, and the elevator, I was warned, tended to break down. But when Tamara Fyodorovna, the landlady, showed me Apartment 81, the interior was spotless, with linoleum floors and wallpaper of alternating vertical brown and yellowish stripes and columns of fleurs-de-lis. Although the kitchen and living room-bedroom were tiny, the place featured a telephone, which many residences in Vladivostok lacked in 1997. The bathroom exhaled a sewerish eau de toilette, but this was not uncommon in Russia. Tamara Fyodorovna closed the door on the smell. “The kitchen’s got all the pots and pans you’ll need for cooking; plates and cutlery, too,” she said.

But in the end it was the bookshelves that made me fall for the place; those and the view of the sea.

The bookcases were glass-fronted and crammed with fiction and poetry and scientific volumes, and I was charmed that my landlady, an oceanographer who had vacated the place to live with her sister, had clipped photographs of writers from the newspapers and taped them up inside the glass. This practice, I would learn, is commonplace in Russia. The eyes of the authors followed me: Pushkin, Lermontov, Dostoyevsky, Chekhov, Akhmatova, and someone new to me: the poet Osip Mandelstam.

Tamara Fyodorovna flung open the curtains on the window in the main room, and I said, “Wow.”

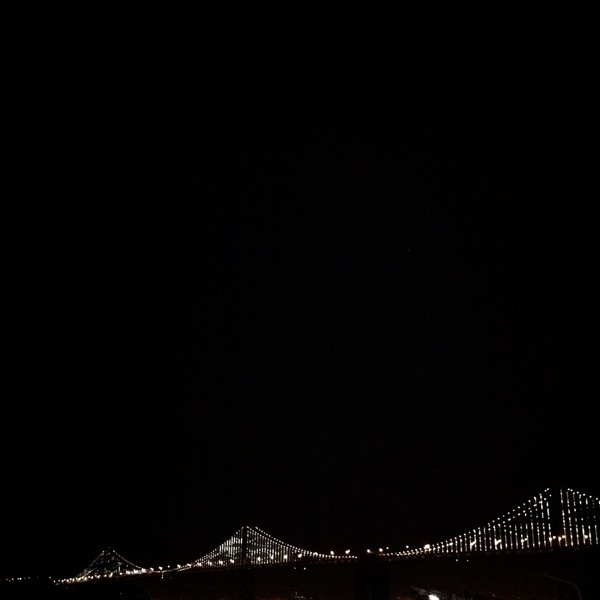

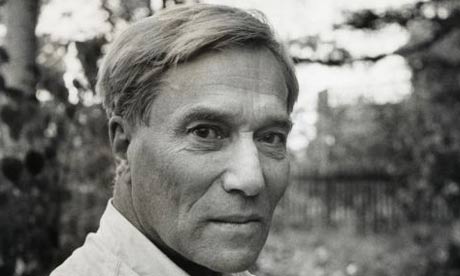

Russell Working on a frozen Amursky Bay in 1997.

Russell Working on a frozen Amursky Bay in 1997.

It was February, and far below, at the foot of the bluff, the sunset had turned the sea ice on Amursky Bay into molten glass. Vladivostok, on the Sea of Japan, lies at roughly the latitude of Marseilles, but the salt water had frozen so thick, coal trucks cut across it to the far shore. Antlike fishermen peppered the surface. Some had lit fires in barrels that would smolder and die overnight. Across the bay, the sunset silhouetted the torn-paper mountains, and because this salient of Russia lies east of China, I wondered if the farthest peaks might be across the border, not forty miles away. On this side, prefab concrete apartment blocks stairstepped down the hill to the waterfront, and a smokestack smudged the air below with a printer’s devil’s inky thumbprint. A giant water pipe snaked alongside a road, shedding insulation.

Yes, of course, I said. I wanted the place.

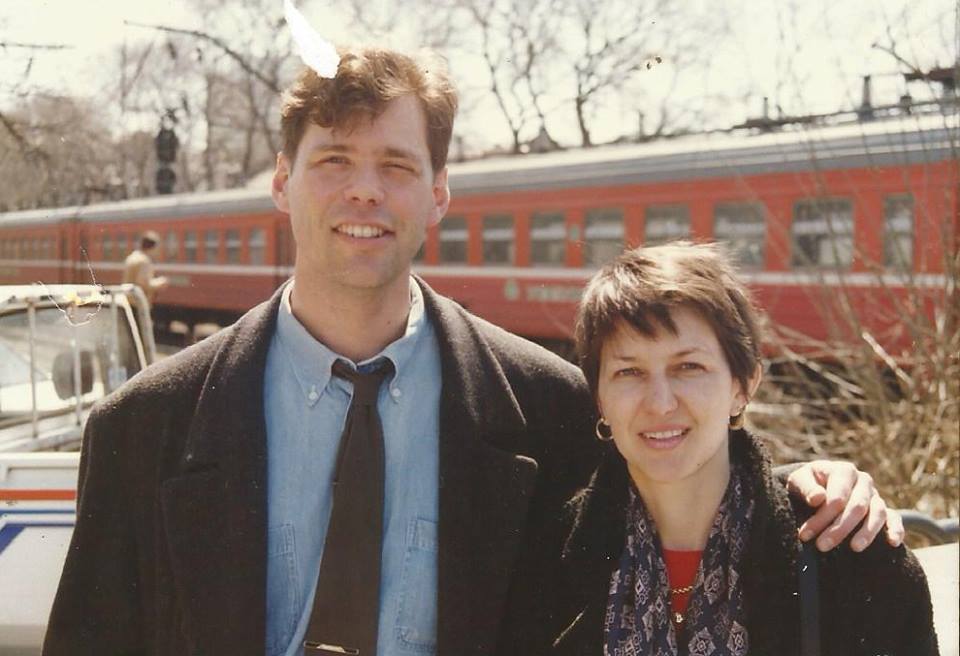

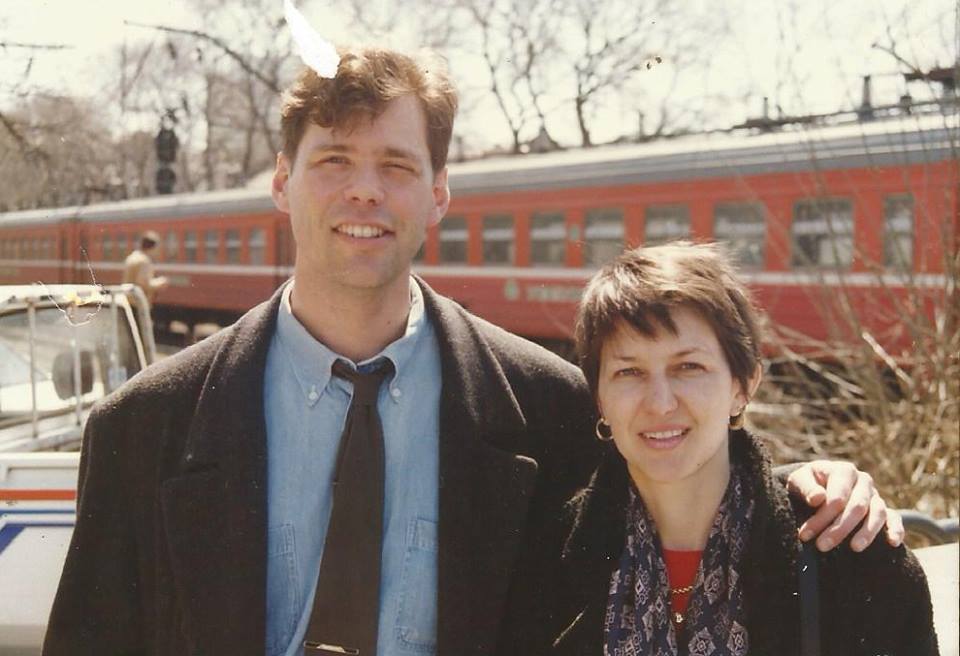

I had quit my job as a reporter on a newspaper in Tacoma, Washington, and moved to the Far East, as Russians call their Pacific maritime (Siberia lies to the west). I was editing a biweekly English-language newspaper for the equivalent of $400 a month, although the crash of the ruble the following year would bring the exchange rate down to $72 a month. But if Russians got by on that, so could I, especially since the newspaper provided an apartment. I had been recruited by the deputy editor, Nonna, whom I had met the previous year when she visited the U.S. on a State Department trip for Russian journalists. She was a former dancer in a contemporary company in Vladivostok, and stood erect, with a ballerina’s grace, in contrast to my writer’s slouch, and had dark hair and a slender figure and green-gray eyes. Sometimes, of their own accord, her body and arms and feet assumed old dance poses. I possess an inner mechanism that surveys non-visible frequencies of the electromagnetic spectrum to determine how interlocutors are receiving what I say, but Nonna had a guileless bluntness of speech. She is now my wife, and I would spend more and more nights at the nearby apartment where she lived with her ten-year-old son, Sergei, until I finally moved in with them, but for now my new pied-à-terre had lessons to teach me about Russia.

On my first night with my clip-out roommates, I poured myself a shot of the liqueur known as balsam: sweet, tea-colored, as strong as vodka, distilled with deer antlers. The taste was medicinal, but hell, it was Russian. Chekhov warned that the stuff would kill me; Dostoyevsky suggested a game of cards. No, thanks, friends; I was content to savor the view of the bay.

So I toasted it all: the apartment, the frozen sea, my little newspaper, Russia. I now possessed, at least as a renter, a few square meters of Russia. Rule the East: that’s what Vladivostok’s name means, and even the Bolsheviks had liked it enough not to rename the city when they stripped the regional maps of tsarist, Chinese, Korean, and indigenous names in the 1920s. Russian civilization, stretched 6,000 miles along a railway line, had taken root where its land mass met China and North Korea and the Sea of Japan. Superficially, Vladivostok could have been any Eastern bloc city: pre-fab concrete apartments, citizens in fur hats, Soviet-era slogans on the rooftops (“60 Years!”), people who rhythmically clap in the ballet, streetcars for poet-doctors to die on. Yet the Far East had changed the Russians. The wolf, object of primordial fear, had been replaced in the imagination by beasts more terrible and beautiful: snow leopards and Siberian tigers. These great cats still prowled the Far Eastern taiga, known as the Ussuri jungle. Though hunted nearly to extinction by poachers who sold their skins and penises in China, tigers still avenged themselves on humans, pouncing on stray villagers or woodsmen. In Chinese restaurants, blond Russian waitresses would take your order, then hand the bill to a translator sitting at a desk in the corner, a little Asian man in a dark suit and white socks, who would render the words in Putonghua for the immigrant cooks back in the smoky kitchen. Shuttle traders ventured to China and returned with great duffle bags stuffed with goods to sell in the outdoor markets: Chicago Bulls jerseys, fake Nikes, “Washington Rednecks” jackets, gloves printed with the words “Old School Clothing Co. This garment made to fit so comfortable you ll wafc touveinz.” (Well, who wouldn’t want to wafc touveinz?) TV hinted at the region’s schizophrenia: when they played M*A*S*H reruns, there was the same dubbed translation you would hear anywhere in Russia, speaking over the faintly audible twang of Alan Alda. There were also subtitles, in Korean.

I turned from the landscape to mingle with my writer roommates, to lean in and peer at the captions under their photographs, as if studying nametags at a conference. This circle of writer friends was something new for me, a loner who had never attended an MFA workshop or drunk absinthe with a coterie of fellow authors in Montparnasse or had faculty colleagues to celebrate a new publication with. (A decade earlier, when I told my editor at a small Oregon newspaper that I had won a short fiction award and would have a book published, he said, “Type up a brief,” and as I wrote I had to grin and admit I was lucky to get even this, there being far less interest in my little triumph than in school immunizations or Kiwanis meetings or a string of bicycles thefts.) I had been devouring Russian fiction and drama since discovering Solzhenitsyn at age thirteen, but I seldom read poems in translation and was mostly unfamiliar with Russia’s great poetry. Pushkin, I knew—who didn’t? Towering poet, duelist, great-grandson of an African slave given to Peter the Great. Akhmatova, too, I had read of, and her haunting “Requiem” written after the arrest of her son during the Great Terror. But Mandelstam: wasn’t he some Soviet versifier? Anyway, he was a strange fellow who claimed his poems began as “auditory hallucinations”: inchoate musical phrases, even hums, a wordless ringing in the ears. He would lie on the divan with a cushion over his head so as not to hear the conversation in our crowded room. He said he was composing.[1] But, hey, I’m a generous guy, and I included him in a toast. You, too, Osip! You’re a writer, man! Down the hatch!

Behind my newsprint roommates, Tamara Fyodorovna’s library drew me, even though I then spoke no Russian beyond the words English has borrowed, such as perestroika, gulag and zek (from Solzhenitsyn), zemstvo and samovar (via Tolstoy), and babushka, which means “grandmother,” not, as Updike and Merriam-Webster had it, “headscarf” (“Ekaterina would bring Bech to his hotel lobby, put a babushka over her bushy orange hair, and head into a blizzard toward this ailing mother”[2]). I had also picked up fragments of the Russian that gleams on the beaches of Nabokov’s prose, like wave-polished glass: guba (lip), chort (devil) and a phrase that I still hope might prove useful someday: in The Gift, he writes of a large, predatory German woman named Klara Stoboy, “which to a Russian ear sounded with sentimental firmness as ‘Klara is with thee (s toboy).’”[3] From Nonna I learned sladky and moya radost (“sweet” and “my joy”). And, because she lived on a stairwell like mine, vanyaet: “it stinks.”

I thumbed through my library with a Russian-English dictionary in hand. Case endings morphed the words, which sometimes made it impossible for a novice to look them up. Lyod (ice) became l’da (“some ice” or “of ice”), l’dom (“with ice”), ledyanoi (“icy”), etc. On a shelf above my bed I found a book whose title I recognized: Анна Каренина. Anna Karenina! Painstakingly I worked through the famous opening line about happy and unhappy families, not in some translator’s simulacrum, but the actual words Tolstoy had penned in a cramped cursive that only his wife and amanuensis, Sophia Andreyevna, could decipher:

Все счастливые семьи счастливы одинаково, каждая несчастливая семья несчастлива по-своему.

I felt the presence of the sage of Yasnaya Polyana, sweaty from working in the fields, wearing a peasant blouse, with straw in his beard. I had no doubt he would find my urban living arrangements disreputable, but who cared? He was with me as surely as my clip-out roommates. As I translated the sentence, the Cyrillic letters blurred. I wiped my eyes.

My landlady’s books—really, they were mine for now, weren’t they?—revealed that Russian took a Joycean view of quotation marks, so that Chekhov’s short story “Spat’ Hochetsya” (“Want to Sleep,” usually translated as, “Sleepy”) looked like this:

— Ну, что? Что ты это вздумал? — говорит доктор, нагибаясь к нему.

— Эге! Давно ли это у тебя?

— Чего-с? Помирать, ваше благородие, пришло время… Не быть мне в живых…

— Полно вздор говорить… Вылечим!

I would later study Russian at Far Eastern State University, but that first night I had only a pocket dictionary to guide me. Chekhov scowled as I looked up his dialogue word by word. Ну meant “well.” Что was “what.” Ты was the informal “you.” I knew это: “it is” or “this.” Доктор—easy: “doctor.” I fought my way along, but it took the Internet to make sense of it. A 1906 translation had appeared, of all places, in Cosmopolitan, which, before it moved on to covering the eleven ways to have naughty sex in every room of the house, had been a literary magazine.

“Well, what’s the matter with you?” asks the doctor, bending over him.

“Ah! You have been like this long?”

“What’s the matter? The time has come, your honor, to die. I shall not live any longer.”

“Nonsense; we’ll soon cure you.”[4]

.

2. Deluge

My apartment was in one of two identical concrete shoeboxes standing on end on the bluff near a clothing factory whose owners brought in Chinese seamstresses to under-price Russians workers, a practice I would later write about for The New York Times. (This was considered newsworthy enough to lead the cover of the Times’ Business Day section, even though the Times editorial board seems to have no problem with the suppression of American working class wages on a far vaster scale by means of corporate-encouraged illegal immigration.) At night Chinese music was piped in, and from outside the building, as the mullioned clerestories began to glow, one could hear the seamstresses singing along. One night shortly after I moved in, during one of the fourteen- to sixteen-hour-a-day blackouts we endured for months, even years, on and off, I trudged up ten flights of stairs in the dark, hoping not to feel the brush of a rat scurrying by or the squish of shit underfoot, for there were neighbors who could not be bothered to walk the dog in winter but instead opened their door to let the wretched thing out to leave little gifts for the rest of us in the stairwell. (And if you have ever wondered why Russians ask you to remove your shoes when you visit, now you know.) I could not see the floor numbers in the dark, so I practiced my Russian by counting off every step and each landing. Odin, dva, chetyre, pyat, shest, sem, vosem… I stayed away from the elevator, afraid the doors might be open and I would stumble into the shaft and fall to my death.

When I arrived at the tenth story (chto pyatdesyat-sem, chto pyatdesyat-vosem…), I groped my way to my steel outer door, but the key did not fit. Had I counted wrong? I hiked up a floor, but where my apartment should have been, the door was of vinyl-covered wood, not steel. Was I too high? Then my mind rewound the video of memory until I was standing out in front, and I realized I had entered the identical building next door to my own.

The apartment was a microcosm of post-Soviet life. In the summer the water could be shut off for up to a week at a time. Sometimes just the hot went out, sometimes the cold, occasionally both. During droughts I learned to keep the bathtub filled with rusty water, so I could scoop out a bucket to flush the toilet or bathe in a washtub. When the water was off, dirty dishes piled up in the kitchen sink. The novelist Mikhail Bulgakov, who knew about Russian plumbing, could have warned me about this, but he was not one of my roommates.

One summer night I was at Nonna’s when the water came back on in my place. Apparently at some point while checking the tap (Nope), I had neglected to turn it back off. Clogged with dishes, the sink overflowed. Tamara Fyodorovna later said that the couple who lived in the apartment downstairs were sitting around the kitchen table enjoying a beer and a smoke when water began dripping through the overhead lamp. I had never met them, but sometimes when I sat out on my balcony, they would lean out the window below in their underwear, trading a beer and a cigarette back and forth. We all watched the sunset together. The night of the deluge, their ceiling began dripping, and this turned into a steady drizzle, the couple would tell my landlady. They banged on the ceiling with a broomstick. The stream became a flood. Rivulets snaked across the ceiling, came down the walls in sheets, gushed through a fissure between the concrete blocks. The husband ran up and rang my doorbell. A jolly throng of neighbors gathered and located Tamara Fyodorovna by telephone, and she ran all the way there and opened the door to my unit. The water was ankle-deep, and my slippers and Russian textbook were floating like little barges. My landlady and a neighbor bailed out my apartment, scooping water out the window.

Nonna mops the floor during a summer typhoon when water was leaking through the ceiling and walls.

Nonna mops the floor during a summer typhoon when water was leaking through the ceiling and walls.

The next day my roommates ribbed me about the disaster I’d wreaked. I should have known, they said. Hadn’t I read Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita or Heart of a Dog? Sure, but it never occurred to me—. Well, the fleas in the carpet had a good soak, Chekhov said. Bulgakov wrote and revised The Master and Margarita between 1928 and 1940, then hid the manuscript away in his apartment, for it could not conceivably be published in its time. This dreamlike allegory tells of a visit by Satan to Stalinist Moscow in the company of a talking cat named Behemoth. It was repressed for decades, published in a bowdlerized version in 1967, and only issued in its final form in 1989. In it, Margarita, the magical lover of an author repressed by the state, trashes and floods the critic Latunsky’s flat. Downstairs a housekeeper is having tea in the kitchen when a downpour begins falling from the ceiling. She runs up and rings the bell to Latunsky’s flat, and Margarita, naked and invisible, flies out the window.[5] As if that weren’t enough, in Heart of a Dog (written in 1925 and suppressed until 1987) a professor transforms a stray mutt into a foul-mouthed, Engels-quoting man who floods the apartment after chasing a cat into the bathroom. Now I wondered if Bulgakov (or his upstairs neighbor) had ever left the faucet on during a water outage.

To make amends for my flood, I gave chocolates to my landlady and, through her, paid the couple downstairs 200 rubles ($33). I thought it would be sporting if to drop by and offered them a box of chocolates and that sheepish foreigner’s grin that excuses so much in provincial Russia. But Tamara Fyodorovna said no. “They’ll triple the price of their repairs if they know you’re a foreigner.” After that when the couple appeared in the window below, I went back inside.

.

3. Luchshe?

Once, early in my five-year stay in Vladivostok, a gypsy-cab driver with prison tattoos on his neck asked me about life in the States: “Is it better there?” When I didn’t at first understand the word “better”— luchshe—he spelled it in the air with his finger. He taught me the meaning by comparing vehicles in the traffic jam around us: “This car is better than that one. This truck is better than that old one.” (He missed his calling as a teacher.) Nonna would have bluntly said, “Yes.” But in halting Russian, I tried to say, sure, some things were better in America, but Russia, too, had its own strengths, and its people and culture had changed the world, and … but he cut me off.

“No! Luchshe, understand? Is it better in America?”

Thwarted by the inaccessibility of subtleties, I just said, “Yes.” Yes, it was better in America, however thrilled I was to live in Russia. Yes, in Los Angeles or Seattle you did not endure water shutoffs for a week at a time. Yes, in America the electricity did not black out all day in the winter, month after month, forcing you to leave the lights on at night, so they would wake you up when the power came on and you could scurry to wash a load of clothes at 2 a.m. Yes, your typical Western male jobholder, returning home after a drink with his friends, did not piss in the elevator but managed to hold on until he could find a toilet to aim at. Yes, middle class reporters and oceanographers back home seldom had to step over drunks sleeping in the hallways of their apartment buildings—and these were not necessarily derelicts; Nonna and I once discovered a vodka-smelling man passed out our stairwell, and he turned out to be a TV journalist who had a program devoted to police chases, so she phoned his wife, who lived in an identical building nearby, and the poor woman came running to fetch her man. Yes, in the bushes outside an American apartment whose residents include a newspaper editor and a city prosecutor, one would not find hypodermic needles, as we did outside Nonna’s. Yes, the only living spaces I ever saw in the States which compared to ours in Russia were in the ghetto; and when, some years later, I entered a Chicago tenement after a gang shooting, I was transported back to Vladivostok, not by the bullet-scarred walls and shattered glass on the floor, but by the graffiti and stink of urine and broken elevator and nailed-up plywood and even the stories I heard, like the one about the South Side pharmaceutical entrepreneur, a stout young man who had hidden his drugs in the garbage chute, and when he leaned in to retrieve them, and leaned a little farther, he fell in and got stuck in the tube seven floors up, and he had to be rescued, people dumping banana peels and coffee grounds and diapers down on him. This sounded like something that would happen in Russia.

“It isn’t like the movies,” I told my ex-con driver, “but yes, in America it’s better. V Amerike luchshe.”

He did not take offense. He seemed pleased at this confirmation. He said, “That’s what I thought.”

Surely all kinds of reasons explain the petty barbarisms of life in a nation of former serfs whom tyrants dating back to Peter the Great had sought to modernize through the use of slave labor, but one factor is communism and its legacy. The system was incapable of allowing people to solve their problems on a local or individual scale. There were no rooftop water tanks to supply the upper floors of hilltop apartments, but central pumping stations that lacked the power to defy gravity and force water up to our faucets when the pressure was low in the summer. Neighborhood boiler houses heated water and pumped it through pipes that snaked through town in the subzero cold and hopped over the streets in squarish arches, to the apartment blocks, where the water trickled out, rusty and lukewarm, in sinks and tubs. In the Soviet Union any accomplishment—writing novels or poems, composing symphonies, designing rockets to Venus, creating the world’s most popular semiautomatic rifle, which would have made Mikhail Kalashnikov a billionaire anywhere else—earned you a tin and plastic medal of Lenin and maybe an apartment or dacha, vouchsafed by the state, which was the owner of everything (assuming, of course, your accomplishment didn’t get you sent to the gulag). In Soviet times, the grocer who had access to sausage held a status higher than a medical doctor like my cousin-in-law, who lived in a tiny studio with a half-sized bathtub. A workaholic could expect a life no better than that of an alcoholic, so why kill yourself to finish that project when you could knock off at 3 p.m. and start drinking on the job with your buddies and go sleep it off in somebody’s stairwell? When the government wanted to collectivize, it went to war against its most successful farmers. It labeled them kulaks, sent in the army, confiscated their pigs and milk cows and barley, deported entire villages to Siberia and Central Asia. When farmers hid food to save their families from starvation, the state rewarded the snitches who ratted them out and seized the caches buried under haystacks. Nothing belonged to you, therefore no one respected property, other than the space within your own apartment, and even that, the government could turn you out of at any moment. Thomas Jefferson, that brilliant, reprehensible, slaveholding genius, was poetically correct that man’s unalienable rights include “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” but there is a blunter truth in Locke’s formulation of “life, liberty, and estate.” Ownership is a human right. The selfishness of owning, conversely, creates a greater respect for that which is public. Like a stairwell.

.

4. “To My Lips I Touch”

Eventually I said good-by to my writers union, whose members wished me well with my fiction—not that they had read me—and told me not to be a stranger. I moved into Nonna’s apartment, which was larger and less cluttered and informed by a more Zen aesthetic. (She is a Buddhist.) Her walls were decorated with black-and-white photographs of half-naked dancers frozen improbably in mid-leap. The view out her window was less spectacular than that of the molten glass of Amursky Bay. Next door was an elementary school and, beyond that, forested hills and an armory, which several years earlier, while a visiting artist from the Martha Graham Dance Company was in town on a U.S. grant, had blown up, rocketing shells across the neighborhood.

Author Russell Working and his wife, Nonna, near a train station in Vladivostok in 1998.

Author Russell Working and his wife, Nonna, near a train station in Vladivostok in 1998.

It turned out that in Nonna’s apartment, too, fragments of Russian literature gleamed. These gems might more properly be called manifestations of Russian culture, but this culture had become known to me through its fiction. A benign Domovoi, or household spirit, kept impishly revealing them. As when the Rostovs prepare to flee Moscow, having emptied their wagons of baggage to make room for the wounded, Nonna insisted that we sit at a table silently for a moment before we set out on a journey. We still do this, and I always feel as if Prince Andrei lies outside, dying, as we pause and look each other in the eye and consider the gravity of speeding at seventy miles an hour in a tin-foil box on wheels. As in Chekhov’s Three Sisters, Nonna superstitiously will not abide whistling indoors (when Masha, deep in thought, starts to whistle a tune, Olga cries, “Don’t whistle Masha. How could you?”). Like Rodion Raskolnikov’s friend, Dmitri Razumikhin, in Crime and Punishment, Nonna called female friends and loved ones moya lastochka—my little sparrow—although no Russian man today would refer to a buddy this way nowadays. And when the fish in cafeteria smelled off, Russians colleagues jokingly said it was “of the second freshness,” as a bartender does when he served bad sturgeon in The Master and Margarita.

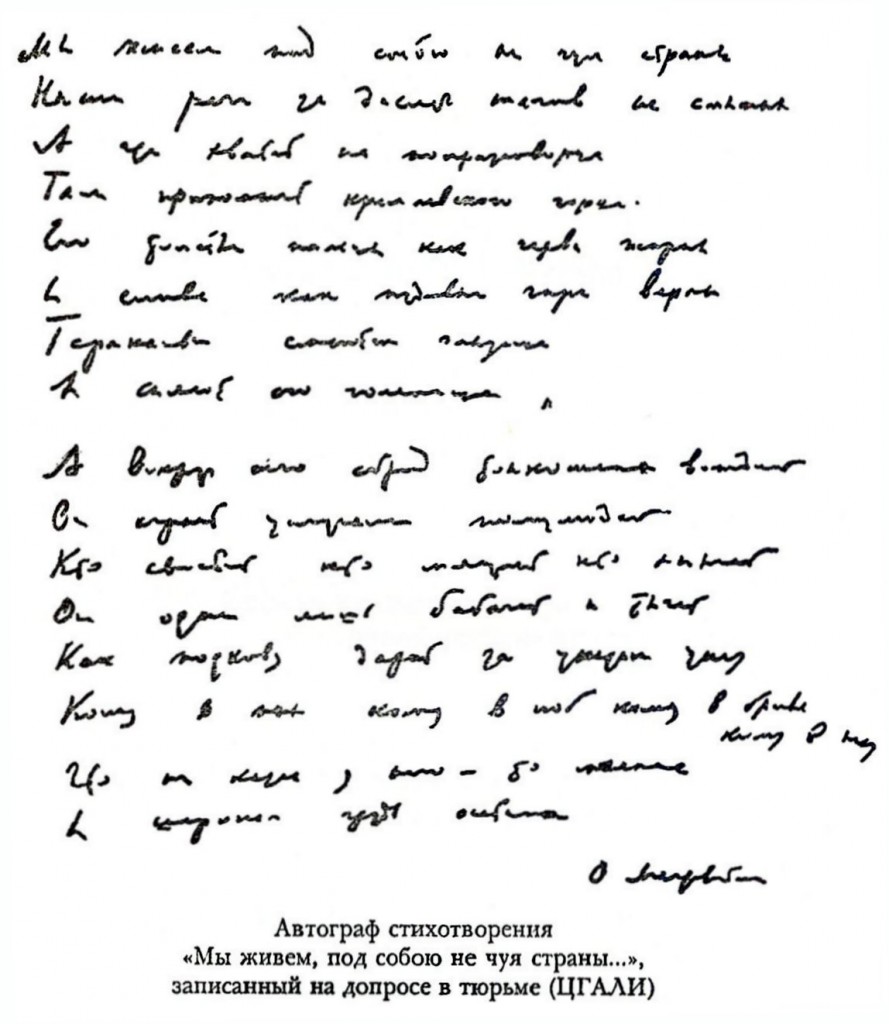

Nonna had something more precious than the Soviet-era editions of classic literature in her bookcases. Among her volumes in Russian and English and French were samizdats, another word bequeathed to the world by Russia. It comes from sam (self) plus izdatelstvo (publishing), but unlike our phrase in English, with its implications of vanity publishing, samizdat bears the sacred aura of the courage of those who risked their lives to preserve forbidden writing. One such book, typed up by Raisa Moroz, a poet friend of Nonna’s, contained page after page of verses, the letters smudged, like lines of smoke from a boiler house, from being typed beneath alternating layers of paper and carbon paper. The book—we still have it—is bound in a blue-gray cover, and the pages are of a cheap, yellowish stock of the sort elementary students use for doodling. The writers are an eclectic mix, from Vadim Shershenevich, who died of tuberculosis in 1942, to the more dangerous (in former times) banned poets, among them the émigré Vladislav Khodasevich. There is a lovely poem by Akhmatova titled “In the Evening.” And on the first page was “To My Lips I Touch,” by my old roommate, Osip Mandelstam. In typing it, Raisa had reversed two of the rhymes, and it was a small victory for my growing Russian that I caught the mistake.

Any poem in translation is an imposter, like Arnaud du Tilh claiming to be Martin Guerre. As José Manuel Prieto writes of translating Mandelstam, “It’s as if the poem were a tree and we could only manage to transplant its trunk and thickest limbs, while leaving all its green and shimmering foliage in the territory of the other language.”[6] The first poem in our samizdat describes an early spring day with its “sticky oath of leaves,” and talks of the poet’s eyes being blown apart by the exploding trees. In a translation by Christian Hawkley and Nadezhda Randall, it concludes:

And the little frogs, like spheres of mercury,

roll their voices into a ball,

twigs become branches

and steam—a white fiction.[7]

Good Lord, I had lived with the fellow and his muttering about auditory hallucinations, and had it not been for the respect with which the rest of my writers circle regarded him, I might have thought him a grafoman, a literary pretender. I now blushed remembering my condescending toast. I was taken aback to discover his astonishing imagery, his sticky oaths of leaves, his exploding trees, his froggy spheres of mercury. And it turned out we shared a geographical connection beyond his newsprint avatar in my old apartment: Nonna said he had been held for a time in a gulag camp in our district of Vladivostok: Vtoraya Rechka, or Second River.

Mandelstam was born to a Jewish merchant family in 1891, although he would later bring his father grief when he was baptized an Evangelical Methodist, evidently to gain entry to the University of St. Petersburg at a time of tsarist restrictions on the admission of Jews.[8] As a boy he studied at the same the democratically oriented Tenishev School in St. Petersburg that Vladimir Nabokov would attend a decade later. Nabokov complains that he was disliked for, among other things, arriving in a chauffeured car, sprinkling his papers with foreign words, and refusing to touch the filthy wet towels in the washroom[9]; but he was of the caste, if perhaps not the attitudes, of those Mandelstam described as “the children of certain ruling families who had landed here by some strange parental caprice and now lorded it over the flabby intellectuals.”[10] Biology lessons horrified Mandelstam, involving, as they did, torturing frogs and suffocating mice in an airless glass bell, but his imagination was ignited by the poet and teacher Vladimir Gippius (or Hippius), “who taught the children not only literature but the far more interesting science of literary spite.”[11] (Gippius would later demonstrate this exquisite science when he brought Nabokov’s first collection of poetry to class, published when the boy was sixteen, and savaged the romantic verses aloud to “the delirious hilarity of the majority of my classmates.”[12]) Mandelstam’s first collection, Kamen or The Stone, was published in 1913.[13]

But of the two great writers it was Mandelstam, not the émigré Nabokov, who would later prove dauntless in the face of state terror. He found it increasingly difficult to publish after the mid-1920s, and in the 1930s he and Nadezhda were alarmed at the cattle trains of peasants being shipped to Central Asia and the legions of dirty homeless farmers who had been evicted from their land in Stalin’s collectivization campaigns and were traveling from town to town in search of work, even as their children and elderly died along the way. The poem that led to his arrest in 1934 was “The Stalin Epigram,” which describes the Soviet general secretary’s “sneering cockroach mustache” and his “fat fingers, like worms, greasy.” When Mandelstam recited the poem in private to Boris Pasternak, Pasternak called it a “suicidal act” and begged him never again to speak it to anyone. As Betsy Sholl has noted in Numéro Cinq, Mandelstam’s wife, Nadezhda (her name means hope), wrote in her memoir, Hope Against Hope, that in reciting the poem, he was “choosing his manner of death.”

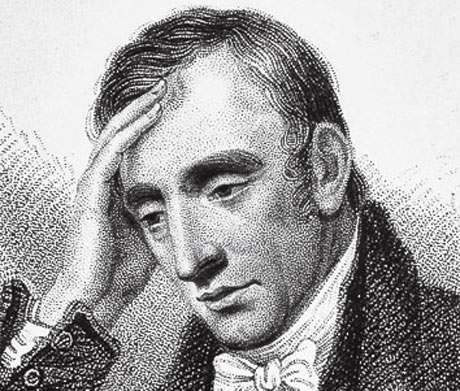

Nadezhda Mandelstam chronicled her life with the poet, his arrest and death, and her survival as an “enemy of the people” in her memoirs, Hope Against Hope and Hope Abandoned.

Nadezhda Mandelstam chronicled her life with the poet, his arrest and death, and her survival as an “enemy of the people” in her memoirs, Hope Against Hope and Hope Abandoned.

When Mandelstam was first arrested, the interrogator had only a description of the poem and a few lines jotted down, Nadezhda writes.[14] He asked Mandelstam to write out the poem, and the prisoner complied. (The manuscript was later discovered in the KGB archives.) Curiously, given the brazenness of the poetic insults, Stalin seemed to admire the poet, or fear his reputation. After the arrest, a Kremlin aide rang Pasternak on the phone in the hall of his communal apartment and ordered him to call Stalin immediately. Pasternak at first thought it a prank. Stalin assured him that Mandelstam’s case would be favorably reviewed, but he asked why writers’ organizations were not speaking out on the poet’s behalf—a disingenuous question, given the terror of the times, and that Pasternak himself had already intervened on Mandelstam’s behalf with Comintern Chairman Nikolai Bukharin and others.[15] The man with the cockroach moustaches fretted about Mandelstam’s stature, as if afraid the poem would outlive his own tyranny (as it has).

As Pasternak later recounted, Stalin asked, “But he is a master of his art, a master?”

Pasternak sought to divert the Georgian leader (or Ossetian, as Mandelstam’s poem had it). “But that isn’t the point,” he replied.

“What is the point then?” Stalin said.

“Why do we keep on about Mandelstam? I have long wanted to meet with you for a serious discussion.”

“About what?” Stalin said.

“About life and death.”

The line went dead.[16]

While some later suggested that Pasternak had refused to vouch for Mandelstam, the Mandelstams believed Pasternak acquitted himself with credit, particularly since Stalin had opened the conversation by offering leniency. Mandelstam said, “He was quite right to say that whether I’m a genius or not is beside the point. … Why is Stalin so afraid of genius? It’s like a superstition with him. He thinks we might put a spell on him, like shamans.”[17]

Mandelstam initially received the astonishingly light sentence of internal exile, and the couple were sent first to the northern town of Cherdyn, then to Voronezh in Central Russia. But the stress took its toll: Nadezhda refers to “the severe psychotic state to which M. had been reduced in prison,” and he tried unsuccessfully to kill himself in Cherdyn. The poet’s auditory hallucinations took the form of men’s voices enumerating his crimes in the rhetoric of Stalinist newspapers, cursing him in the foulest language, and blaming him for the ruin he had brought on friends to whom he had read the “Epigram.” When he and Nadezhda took walks, Mandelstam kept looking for Akhmatova’s corpse in the ravines outside town.[18]

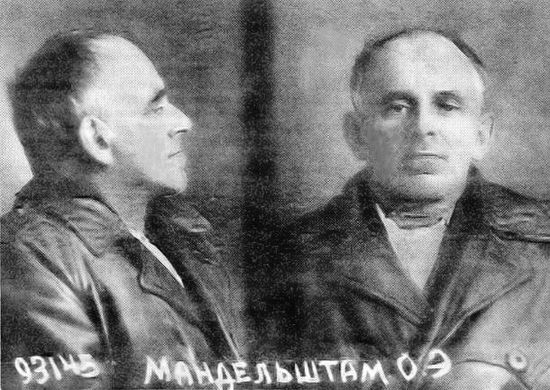

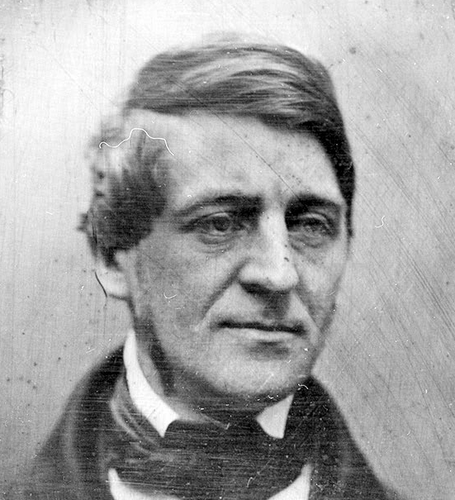

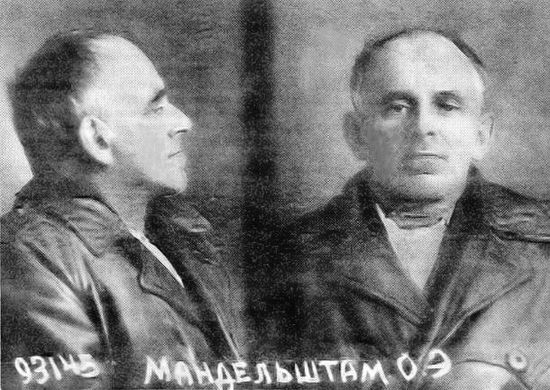

Osip Mandelstam in a 1938 prison mug shot.

Osip Mandelstam in a 1938 prison mug shot.

His mental stability soon returned, and he began composing at a frenetic pace. In an attempt to save his life, he wrote an “Ode to Stalin.” (Possibly a vague memory of this had colored my earlier, ignorant view of him.) But he was rearrested in 1938, and on September 9 he was sent from Moscow to Vladivostok. Anne Applebaum describes the prisoner transits in terms that recall the cattle trains of the Holocaust, with guards denying the prisoners water and children dying en route.[19] Mandelstam traveled for more than five weeks on the 6,000-mile journey, arriving October 12.

.

5. Tranzitka

The gulag camp in our Vtoraya Rechka district of Vladivostok had once occupied a vast swath of territory. In the 1930s, as many as 56,000 prisoners were held at any given time in the transit camp, known as a tranzitka, the historian Valery Markov said in an interview Nonna turned up for me.[20] The camp was for years the only Pacific port shipping prisoners to the mining camps of the Kolyma River valley, beyond Magadan, 1,300 miles to the northeast. The tranzitka was divided into men’s and women’s sections, with criminals segregated from politicals, intelligentsia, members of Comintern (an international communist association), and Russian workers who had built the section of the Trans-Siberian Railroad which originally cut across the hump of China that extends into the Russian Far East (like many who had been abroad, they were arrested upon their return to the Soviet Union). While some prisoners remained in Vladivostok to construct a navy port and process fish, most were heading north.

Shortly after his arrival, Mandelstam wrote to his family. The letter from Barracks No. 11 informed his brother Alexander (Shura or Shurochka) and his wife Nadezhda (Nadenka or Nadya) that the OSO, or the Special Council of the State Security Ministry, had sentenced him to five years for “counterrevolutionary activities.” There could be no hope of an appeal. Solzhenitsyn writes of the OSO: “There was no appeals jurisdiction above it, and no jurisdiction beneath it. It was subordinate only to the Minister of Internal Affairs, to Stalin, and to Satan.”[21] Mandelstam’s letter reads:

I left Moscow Butyrka [prison] on September 9, arrived October 12. Health is very weak. Exhausted to the utmost degree. Lost weight. Almost unrecognizable. But I don’t know if it makes sense to send things, food, and money. Still, try. I am very cold without [proper] clothes.

Dear Nadenka, I don’t know if you are alive, my beloved. You, Shura, write to me about Nadya right away. This is a transit point. They didn’t take me to Kolyma. Spending the winter here is possible.

—Osya [Osip]

[P.S.] Shurochka, I’m writing some more. For the last days I went to work, and it improved my mood.

From our transit camp, they send people to permanent camps. I have obviously gotten onto a “substandard” list, and I need to prepare for winter.[22]

A clearer picture of the Vladivostok camp emerges in the memoir Journey into the Whirlwind by Yevgenia (Eugenia) Ginzburg, who survived eighteen years in the gulag and in Magadan. The daughter of a pharmacist, she taught at Kazan State University, and she was the mother of the novelist Vassily Aksyonov. In Journey she writes of being held for two years in solitary, then traveling to the Pacific Coast in a freight car with seventy-six other women. On the outside was chalked, SPECIAL EQUIPMENT. She thought she might have arrived in Chornaya Rechka, but that distant station outside Vladivostok seems unlikely. Markov says all prisoners disembarked at Vtoraya Rechka, near the tranzitka. The station where millions of doomed zeks disembarked is now a small platform where I have caught the commuter train many times. Ginzburg writes:

It was night when the train stopped. Outside, a reinforced team of guards was waiting to take delivery. The German shepherds, straining at their leads, made a terrific din.

“Everyone out! Form up in ranks of five!”

Suddenly we could smell the sea air. I felt an almost irresistible desire to lie flat on the earth, spread out my arms, and disappear, dissolve into this deep-blue space with its tang of iodine.

Suddenly despairing cries were heard: “I can’t see! I can’t see anything! What’s the matter with my eyes?”

“Girls—please give me a hand. I can’t see a thing! What’s happened?”

“Help, help, I’ve gone blind!”

It was night blindness, by which about a third of us were affected immediately [as] we set foot on Far Eastern soil. From dusk to dawn they could see nothing and would wander about, stretching out their hands and calling to their comrades for help.[23]

The tranzitka occupied a vast, filthy area surrounded by barbed wire and filled with zeks who resembled “a crowd of beggars, refugees, bombed-out people,” Ginzburg recalls. But the new arrivals, who had spent two years in solitary in Yaroslavl and Suzdal, were so feeble, even the other prisoners looked on them with pity as they trudged through the gates in an interminable gray river. The barracks, filled with three-level bunks, were infested with bedbugs, making it impossible even to sit there. Zeks rushed outside dragging out boards and broken cupboards to sleep on in the summer weather. Some just lay on the ground in their prison uniforms. The air stank of the ammonia and chloride of lime that was dumped in the latrines.

Absurdly convicted under terrorism laws, Ginzburg and the other newcomers constituted the lowest caste of prison society, and were marked for heavy labor, along with the “Trotskyites.” At the top of the social pyramid were “respectable” criminals guilty of transgressions such as embezzlement and accepting bribes, followed in descending order by “babblers” (tellers of political jokes), counterrevolutionaries (like Mandelstam), alleged spies, and accused Trotskyites. Of course, one need not have done anything at all to be imprisoned on any of these charges. Ginzburg and the others from her train had not seen the sunlight for more than two years of solitary, were suffering from scurvy and pellagra, and had barely survived their train journey, but like Mandelstam they had to quarry stone under the July sun, the rocks radiating heat. Grit worked its way between their teeth. At night, under the open sky, it was hard to sleep because of the screams and moans from hundreds of voices. Many descended into a “camp stupor,” Ginzburg writes. Diarrhea reduced people “to their shadows.” Only the dying were admitted to the hospital.

One of the most striking moments in Ginzburg’s account of her time in the tranzitka arrives with a trainload of men with shorn heads, who plodded wearily in prison boots into a yard separated from the women by barbed wire. The men seemed somehow defenseless—they would not know how to sew on a button, to wash their clothes on the sly. “Above all they were our husbands and brothers, deprived of our care in this terrible place,” Ginzburg writes.[24] One of the men noticed the women and cried out, “Look, the women! Our women!” An electric charge flashed between the two sexes across the barbed wire. Men and women were shouting, reaching out to each other. Nearly everyone was sobbing.

“You poor loves, you poor darlings! Cheer up, be brave, be strong!”

The emotional tension needed an outlet in action, Ginzburg writes, and these men and women in rags began throwing presents to each other across the wire.

“Take my towel! It’s not too badly torn.”

“Girls! Anybody want this pot? I made it from a prison mug I stole.”

“Here, take this bread. You’re so thin after the journey!”

There were also cases of love at first sight, when men and women would stand by the barbed wire and feverishly gaze into each other’s eyes, and talk and talk.

Every day the men would write us long letters—jointly and individually, in verse and prose, on greasy bits of paper and even on rags. They put all their insulted, long-pent-up manhood into the pure vibrant passion of these letters. They were numbed by pain and anguish at the thought that we, “their” women, had undergone the same bestial indignities as had been inflicted on them.

One of the letters began: “Dear ones—our wives, sisters, friends, loved ones! Tell us how we can take your pain upon ourselves!”

.

6. “When Later?”

In Robert Conquest’s The Great Terror, he writes that Mandelstam “seems to have become half-demented, and was rejected from the transports.”[25] But there was no sign of mental incapacity in the letter to his brother. Despite his ailing health, the poet hauled rocks, and October of 1938, he told his work partner, a physicist named L., “My first book was The Stone, and the last one will be a stone, too.”[26] In his thin leather coat, he suffered in the camp along the wind-threshed sea, where, in December, milky swirls of salt-water slush condense into heaving skeins of ice that weave together and harden into pavement for coal trucks. The guards seem to have limited his rations, possibly because he was not meeting work quotas.

L. spent twenty years in the gulag, and upon his release he told Nadezhda (believably, she felt) that in Vtoraya Rechka he became friends with a criminal inmate named Arkhangelski, who lived with a handful of fellow thugs in a loft in the barracks. One night Arkhangelski invited L. up for a poetry reading. Curious about what sort of verses the cons favored, L. accepted. As recounted by Nadezhda:

The loft was lit by a candle. In the middle stood a barrel on which there was an opened can of food and some white bread. For the starving camp this was an unheard-of luxury. People lived on thin soup of which there was never enough—what they got for their morning meal would not have filled a glass. …

Sitting with the criminals was a man with a gray stubble of beard, wearing a yellow leather coat. He was reciting verse which L. recognized. It was Mandelstam. The criminals offered him bread and canned stuff, and he calmly helped himself and ate. Evidently he was only afraid to eat food given him by his jailers. He was listened to in complete silence and sometimes asked to repeat a poem.

In his collection of fiction, Kolyma Tales, Varlam Shalamov, who passed through the Vladivostok tranzitka and survived seventeen years in the gulag, imagines the death of Mandelstam. The short story is titled “Cherry Brandy,” from a phrase in one of Mandelstam poems. As Shalamov’s Mandelstam lies dying, he stuffs bits of bread in his bleeding mouth, gnawing with teeth loosened by scurvy. His fellow zeks stop him: “Don’t eat it all. Better eat it later, later.” The poet understands. You’re dying. Leave it for us.

He opened his eyes wide without letting the bloodstained bread slip from his dirty, blue fingers.

“When later?” he uttered distinctly and clearly. And closed his eyes.

He died that evening.

Two days later they “wrote him off.” His resourceful neighbors managed to keep getting the bread for the dead person for two more days during the bread distribution; the dead man would raise his hand like a puppet.[27]

In spring the dead were hauled out of town for burial, Markov says, but in winter they were dumped in a trench that had been part of the city’s tsarist-era fortifications. This is where Markov thinks Mandelstam was buried, behind a movie theater called Iskra (spark). The cinema stands on the edge of a shabby neighborhood of khrushchevki—the five-story concrete buildings that the eponymous premier built across the Soviet Union. Movie theaters have been renovated all over Russia, with plush seats and posters on the walls, but at that time, at least, Iskra still had fold-down wooden chairs, like those in a school auditorium. Nonna and I once watched the movie Armageddon there, not knowing, as Bruce Willis and a team of wisecracking Yankee misfits saved the world from an asteroid the size of Texas, that a multitude of ghosts quarried rock in the dark, among them Mandelstam’s. An eyewitness in the late 1930s saw zeks on the corpse detail wielding clubs to shatter the skulls of the dead, to ensure that nobody was buried alive. Years later workers digging the foundations of the khrushchevki turned up skeletons, Markov says. A spontaneous soccer game broke out, the workers kicking the skulls about.

In 1998, six decades after Mandelstam’s death, a monument was erected to the poet near where Barracks No. 11 had stood. But vandals expressed their admiration for the great poet by disfiguring the site with graffiti. During the five years I lived in Vladivostok, the topic of erecting an adequate monument was a matter of debate in the papers. Eventually the city raised a statue in a better location, near a university.

© 2013 Valentin Trukhanenk

One day Nonna I walked out to what is said to be the sole remaining building of the vast tranzitka, on Ulitsa Russkaya, out past a small hospital and the Vietnamese market with its tin-roofed stalls and shuttle traders. It was an unremarkable wooden structure that had served as an administrative building. It now belonged to a private business—I forget what kind—and with journalists’ pushiness we marched in to look around at an office with too many phones and a couple of typewriters on the desks. The ladies of the office were intrigued that a foreigner had popped in. You wondered what papers might have been processed here sixty years earlier, if the administration signed off on transport trains, consigned Ginzburg and Shalamov and the doomed lovers to Kolyma, or decreed that one No. 93145 Mandelstam O.E. was unfit for transport to the Far North.

Several miles south, across the street from Vladivostok’s central train station, a statue of Vladimir Lenin looms, clutching his worker’s cap and thrusting his finger (There!) to guide travelers who have lost their way. But unlike in Magadan, where a giant masklike monument to the dead of Kolyma, two million or more, stands on a mountaintop visible from all over the city, no suitable memorial exists in Vladivostok to the victims of the socialist paradise Lenin bequeathed. No plaque at Vtoraya Rechka station commemorates the millions who arrived to break rocks or build wharves or trudge up the plank into freighters that plied the slaty summer seas to the Far North: poets, historians, bribe-takers, murderers, pregnant women, railroaders who had criminally sojourned in China, children who were kidnapped by the state and raised in orphanages to curse their parents as traitors and scum.

All that remain are khrushchevki—those aging apartment blocks. And a movie theater where an asteroid strike was averted. And skeletons in mass graves that will never be exhumed. And a wooden office building on a busy street that ends at a rocky waterfront glittering with broken vodka- and beer bottles, like fragments of an unknown language. Also poems in samizdats. And photographs of writers taped up in bookcases; these, too, survive.

— Russell Working

.

Russell Working is a journalist and short story writer whose work has appeared in publications such as the New York Times, The Atlantic Monthly, The Paris Review, The TriQuarterly Review, and Zoetrope: All-Story.

His collection, The Irish Martyr, won the University of Notre Dame’s Sullivan Award. He was the youngest winner of the Iowa Short Fiction Award, for his book Resurrectionists. He is a staff writer for Ragan Communications in Chicago and has taught in Vermont College of Fine Arts’ MFA program in creative writing.

Russell’s journalism has often informed his fiction. His Pushcart Prize-winning The Irish Martyr,written after an assignment in Sinai, tells of an Egyptian girl’s obsession with an Irish sniper who has enlisted in the Palestinian cause. After reporting on the trafficking in North Korean women as wives and prostitutes in China, he wrote the short story Dear Leader, about a refugee from the North who is sold to a Chinese peasant.

Russell formerly worked as a staff reporter at the Chicago Tribune. There he exposed cops and a Navy surgeon general who padded their résumés with diploma mill degrees, and covered the international trade in cadavers for museum exhibitions.

He lived for nearly eight years abroad in Australia, the Russian Far East, and Cyprus, reporting from the former Soviet Union, China, Japan, South Korea, Mongolia, the Philippines, Turkey, Greece, and aboard the USS Theodore Roosevelt. His byline has appeared dozens of newspapers and magazines around the world, including BusinessWeek, the Boston Globe, the Los Angeles Times, theDallas Morning News, the South China Morning Post, and the Japan Times. He began his career at dailies in Oregon and Washington.

.

.

Russell Working on a frozen Amursky Bay in 1997.

Russell Working on a frozen Amursky Bay in 1997.

Nonna mops the floor during a summer typhoon when water was leaking through the ceiling and walls.

Nonna mops the floor during a summer typhoon when water was leaking through the ceiling and walls. Author Russell Working and his wife, Nonna, near a train station in Vladivostok in 1998.

Author Russell Working and his wife, Nonna, near a train station in Vladivostok in 1998.

Nadezhda Mandelstam chronicled her life with the poet, his arrest and death, and her survival as an “enemy of the people” in her memoirs, Hope Against Hope and Hope Abandoned.

Nadezhda Mandelstam chronicled her life with the poet, his arrest and death, and her survival as an “enemy of the people” in her memoirs, Hope Against Hope and Hope Abandoned.

Osip Mandelstam in a 1938 prison mug shot.

Osip Mandelstam in a 1938 prison mug shot.