.

1.

A couple lived on a farm far away from the rest of the world. They had land to grow vegetables, chickens that gave eggs, and a well for water. Nearby, there was a stream jumping with fish and, right at the edge of their land, a wood with trees to chop for the fire.

The couple had everything they needed except for one small thing.

On their wedding day, to mark the occasion, the couple had planted an apple tree at the entrance to the wood and, exactly five years later, it bore fruit for the first time, as though celebrating their anniversary.

“Surely, it’s a sign,” the wife said.

The husband patted her stomach and smiled.

The years passed and the woman’s belly showed no swell, and though deep love slept within them, the couple stopped lying with each other.

The man took to going to the edge of the wood at the end of his working day to sit underneath the apple tree. At times, when he hadn’t come home for supper, the woman would go looking for her husband only to find him sleeping against its trunk.

“See what you’ve done,” she said, one evening, while helping her husband to his feet. “You’ve worn a dent in the tree with your back.”

She smiled through a sting of jealousy. Being of a sensible nature she shook her head and laughed at herself, returning to the calm she knew.

One day, when the man was tired from his work and felt the cool of the setting sun in his bones, he went to the wood and sat, leaning in the nook he had worn in the trunk of the tree. This groove his body had made over the years seemed to welcome him. Before long he drifted off to sleep.

In his dream, he was exactly where he’d sat to rest but the heat was unbearable. He took off his shirt, then the rest of his clothes, and lay naked at the foot of the tree. Despite the heat, a blanket of cool damp leaves covered the earth beneath the shade.

I wish there was a breeze, he thought, and closed his eyes.

What felt like a cool breath, ran over him, making the fine, blonde hair of his stomach stand and his skin bump and tingle. When he opened his eyes, the five-flowered blossoms on the apple tree waved. The branches swayed. He knew it wasn’t the wind but the tree itself fanning him. The branches came toward him, wrapping around his body and pulling him up and in until he was pressed against the trunk of the tree.

He placed his hands on the bark and looked up at the dance of the branches above.

“How beautiful you are,” he said, then kissed the tree tenderly. “How I’ve ignored you all this time. Have I been blind?”

The groove he had made with his back was now hip-height as he stood, and it yielded as he pressed against the tree. Leaves whispered in his ear and the smell of apple blossom filled his head and he became aroused. He made love to the tree in way that dreams allow. As he came, the tree caved, and he sank deep inside the damp, darkness of the hollow.

When he woke, he found he was lying naked on the earth. He tried to piece together what had happened, grasping at images from his dream, but, like snowflakes, they disappeared the instant he touched them. All that remained was a feeling of deep shame. He was cold and became self-conscious. Dressing quickly, he hurried home, his head thick with fog and full of fear and the sense of something very important lost.

.

2.

The tree waited for the man to return. Every day, as the sun rose, the tree unfurled its leaves to the cottage in the distance. Every afternoon, the tree waited, hoping to see the man appear walking towards her through the long grass. But he was never again to rest himself on her bark.

As the days grew hotter, apples burst from its branches, tiny and sore. One, sprouting from the tip of the highest branch, caused the most pain. Within a week it had grown ten times the size of the others. It weighed down the branch until it rested on the earth. As the summer had its way, while the other apples matured and fell, the huge fruit stayed and did not stop growing.

One morning, as the tree opened for the sun, something was different. The large apple had disappeared. The branch that had held it now led inside the hollow that had been made the last time she saw the farmer. The tree pulled to bring the fruit out, bark cracking from the strain. The tree called upon its deep roots to help. And with the strength of the earth itself, it strained until there was a cry. A human cry. Now the branch came easily. It rustled out from the hollow and with it a baby boy, the tip of the branch attached to the boy’s belly.

The tree slid some branches under the baby and lifted it off the ground. The tree wept leaves and blossoms of joy at the sight of the boy. The boy screamed and cried. The tree curled a branch around a rock and bashed its trunk until its bark split. It brought the boy to the bark and he drank the sap.

The tree was devoted to the boy. It shaded him under its branches when he was hot and sheltered him in the hollow when he was cold. It let him drink his fill of its sap, held and rocked him till he slept. And the boy was content, playing among the roots. The farmer never returned.

When the boy had been with the tree for seven years, and the autumn had painted them both brown and orange, a tiny figure appeared in the horizon and came towards them. The tree became frightened for the boy, ushering him into the hollow and concealing it with its branches.

A little girl emerged from the grass swinging a small basket. She sat on the ground and picked the apples, throwing away the bruised and wrinkled but keeping the golden and shiny for herself. The girl began to sing. Clear, high and pure, her voice hung in the air like a sweet smell.

The tree resisted as the boy pushed at the branches to escape the hollow. The boy growled, a sound he’d never made before. The little girl jumped. The growling became a whimper. The girl looked at the tree, glanced back at the cottage in the distance, then stood. Flattening down her skirt, she tip-toed towards the tree trunk.

“Hello,” she said, tugging at the branches that covered the hollow. The boy struggled on his side, too, and soon the two of them were standing face to face.

“Who are you?” she said.

The boy reached out and touched her hair then touched his own. The girl spat on the hem of her skirt then wiped the earth from his face. The tree shivered at this, its leaves whispered a warning.

“That’s better,” the girl said.

The boy glanced back at the tree and then at the girl.

“I’m not supposed to come here,” she said. “It’ll be our secret.”

She held her finger to her lips.

“I have to go, but I will come back.” The girl smiled, picked up her basket, and off she skipped.

The boy run after the girl until the branch that led from his belly to the tree snapped him back. He pulled at the branch. The tree felt those tugs deep in its sap. As the girl disappeared over the horizon, the boy dropped to the earth with a thump.

The boy didn’t return to the tree straight away but sat watching the sun grow tired and heavy until it sank from the sky to rest. When the chill of the dark came to rouse him, the boy stood and, with his foot, made a circle of turned-up soil around the tree, mapping his boundary.

As the autumn darkened, the girl came to the tree every afternoon. She brought books with drawings inside and taught the boy about the world beyond the field. Even after he understood her talk, he would not speak back. He was ashamed of the rustling whispers that came out of his mouth when he practiced alone. The girl didn’t seem to mind that he was always silent – except when he laughed. He couldn’t keep the wet, sticky clacking sound inside.

The next summer, while the tree was busy bearing fruit, energy low, busy with so much life, the girl came all day, every day. The children started whispering. They were keeping secrets. When they did this, the tree would tickle them with leaves or drop apples on their heads. They’d laugh then move further away.

One sticky, late summer’s day, under the pale blue sky, the boy ran to greet the girl. This time they lingered at the very limit that his branch allowed. The summer had been a hot one, and the apples on the tree had grown heavy and begun to drop before their time.

When it happened, it was like an explosion. Every branch shook, every apple fell. When the surge passed, the tree saw the girl and the boy running across the field, hand in hand. In the girl’s other hand, shears glinted in the dying sun.

.

3.

The boy’s hand felt crushed by the girl’s, but he didn’t mind. He ran through the field, down and then up the hill. He breathed deeper than before. Running in a straight line, knowing he could go on, running until he dropped, amazed him. But soon he grew tired and felt sharp, stabbing pains in his chest. He’d never felt so frightened. He stopped, trying desperately to breathe. The girl didn’t seem to notice. She pulled, dragging him on.

Ahead he saw a cottage, just like the pictures the girl had shown him. It was where people lived. People like him.

At the door, the girl said, “Wait here,” and kissed him on the cheek. He nodded and watched her go in. The door clicked but didn’t catch and remained slightly open. The boy was glad for a moment to breathe and rest but, left alone for the first time in his life, he wondered if he had made a terrible mistake. He watched through the gap in the door.

“Daddy! I’ve brought my friend home,” the girl cried.

“A friend? Where?” The father squinted at his daughter. “Don’t leave the child outside.”

“It’s the boy I’ve been telling you about,” she said, “the boy from the tree.”

“The apple tree, in the far field?” her mother asked. “That’s your father’s tree.”

“I’ve told you to stay away from that tree,” her father scolded. “And it’s not my tree!” He glared at his wife. “No wonder her head is full of nonsense.”

The girl ran out the door and grabbed the boy by the hand. He was scared and reluctant to come, but she dragged him in and helped him onto a chair.

“See,” she said, pointing at the boy.

“Oh yes, he’s a lovely boy, isn’t he?” the mother said. “He looks a little familiar.” She winked at her husband.

“Can we get him some clothes?” asked the girl.

“You’re not dressing a piece of wood,” her father snapped.

“When I start school, he can come too,” said the girl. “We can say he’s my little brother.”

The father slammed his hand on the dinner table.

The mother laughed. “He does have his father’s eyes.”

At that, the girl’s father jumped up, lifted the boy from his chair, snapped him in half over his knee, and threw him on the fire.

As he burned, the boy saw the little girl cry on her mother’s lap while the father picked up an axe and walked out to the field.

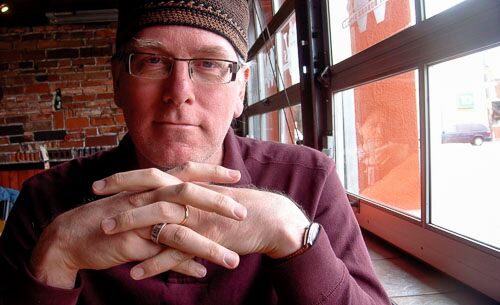

—Paul McVeigh

.

Paul McVeigh began his career as a playwright in Belfast before moving to London where he wrote comedy shows, which were performed at the Edinburgh Festival and in London’s West End. After turning to writing prose, Paul’s short stories were published in literary journals and anthologies, and were read on BBC Radio 3, 4 & 5. He is co-founder of London Short Story Festival.

The Good Son, Paul’s first novel, won The Polari First Novel Prize, The McCrea Literary Award, was Brighton’s City Reads 2016 and chosen for the UK’s World Book Night 2017. It was also shortlisted for The Authors’ Club Best First Novel Award, a finalist for The People’s Book Prize and is currently shortlisted for the Prix du Roman Cezam in France. His work has been translated into seven languages.

After living in London for 20 years Paul has returned home to live in Belfast, Northern Ireland.

McVeigh will be in the U.S. in October to promote his novel. Catch him at Litquake in San Francisco or the Los Gatos Irish Writers Festival.

.

.

Wellington Street, downtown Chilliwack

Wellington Street, downtown Chilliwack

Cultus Lake, seen from Ryder Lake

Cultus Lake, seen from Ryder Lake

Nephin mountain

Nephin mountain  Amanda Bell and daughter near the summit of Mount Nephin

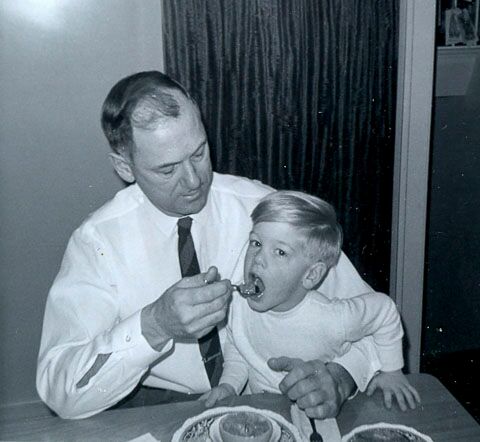

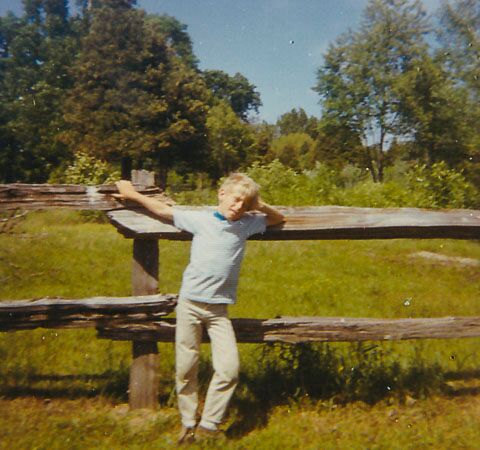

Amanda Bell and daughter near the summit of Mount Nephin Author 1971 or 1972

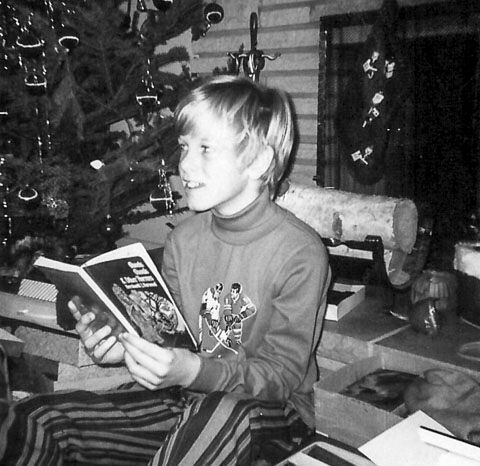

Author 1971 or 1972  The author at Pontoon, 1972

The author at Pontoon, 1972 Author’s grandfather and brother collecting turf

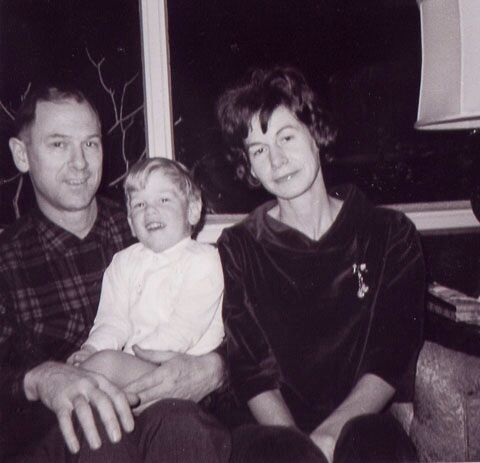

Author’s grandfather and brother collecting turf The author and her brother

The author and her brother Mayo Road

Mayo Road