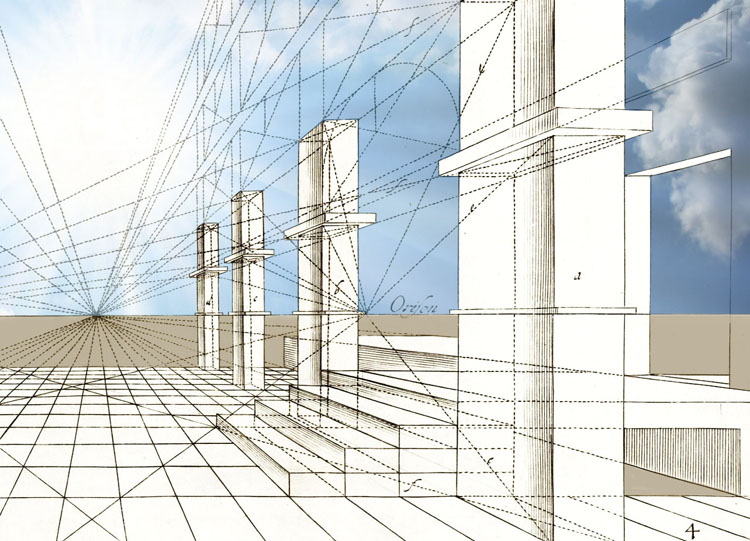

Tower of Babel (for Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman) – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, 48 x 38 inches, 2016

Tower of Babel (for Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman) – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, 48 x 38 inches, 2016

.

This is the Last Call issue because it is the final issue. Numéro Cinq will cease publishing new work when we complete the roll-out in August. The site will remain live forever (or whatever forever amounts to in Internet years). It will also be backed up and archived, so that as long as there is electricity there will be a Numéro Cinq somewhere, a monument to the collective efforts of all our editors, writers, artists, and readers.

I’m stopping the magazine because we are soaring, reputation rising, the quality of new work never better. We have a well-oiled infrastructure in place. The masthead is replete with intelligent, gifted, dedicated people. But, paradoxical as it might seem, this feels like the perfect moment to sign off, mount up, and ride into the sunset.

The magazine is named for an imaginary terrorist organization in one of my short stories. It was born under the flag of the outsider: rumbustious, experimental, anti-capitalist, and defiantly non-institutional. We did it the wrong way on purpose. No submissions, no submission fees, no financing, no donors, no board, no contests to raise money, no grant applications, no splashy design help, no tech experts, no institutional support, no ads. I was thinking of samizdat, underground mags run off on mimeograph machines. I was moreover impatient with what I perceived as a general need for prior approval. (Oh, I’m going to start this project, research that, publish this — as soon as I get a grant.) And I was also reacting to a perceived threat: the advent of electronic publishing, the decline of bookstores. Everything was going to hell in a hand basket. But at Numéro Cinq we opted to embrace the new and see what advantages could be earned. Forget fear, ignore cultural malaise, we thought. Just try a little something and see where it will go. Have fun, be earnest and uncool, exhibit naive bravado, panache.

We also intended above all to honour the writers. One of the chief problems with print magazines is that they disappear shortly after publication. If you’re lucky, you have five copies and can perhaps find one in the stacks at the college library. The analogous problem with online publications is that after the flash of publication, your work disappears into the anarchic bowels of unsearchable archives. I designed NC to avoid these pitfalls. Instead of dumping the entire issue at the beginning of the month, we opted to publish one or two pieces per day so that each author had a day in the sun at the top of the front page. Then I added the RECENT ISSUES section; every writer’s name would be linked on the front page of the magazine for three months. And then I solved the impenetrable archive dilemma by designing multiple transparent search pathways and a logical archive organization: genre contents pages (linked to buttons down the right column but also lined to dropdown menus in the nav bar), issue by issue links under BACK ISSUES (in the nav bar), also special feature pages (linked in the nav bar) and our author archive pages (for authors who have appeared regularly in the magazine). We also opted to pay special attention to translators; we have a translators’ content page (so every translated item is entered in its own genre contents page and again under the translator’s name on the translation page). This mean seem a bit arcane, but it’s important to give a sense of how much care we tried to take with that precious commodity, our writers. (I also ruthlessly deleted any cross-eyed, stupid, ad hominem, unsupported comments that showed up under posts.)

NC was always meant to be a community, not a distant institution and especially not a submission portal that no one ever read or engaged with. We published mostly be invitation. But if a person engaged intelligently with the community (in comments, on Facebook, on Twitter), that person was apt to get an invitation. Many of or writers started as readers. We also used the set essay series — What It’s Like Living Here, Childhood, My First Job — as entry points for developing writers or gifted amateurs. You may all remember the periodic call for submissions.

In brief, this is what we were, what we tried to be. But it is the fate of revolutions to form governments and transform into the thing they rebelled against. The direction of all is toward entropy and stasis. Now we hope we can avoid that fate by simply stepping aside, assigning ourselves to the evanescent.

That said, the August issue is a revelation. I discreetly put out the word and, Lo! — it was like the housecarls and shield lords (if you can imagine also many female shield lords) gathering to make a last stand for the old cause. Writers leaped at the chance to appear in the last issue. Some put off other deadlines to finish work for NC. Long promised work suddenly materialized. I was touched over and over at the words people wrote to me about what the magazine has meant, how important it has become. (Okay, I have difficulty with praise. People have written things in the past weeks such that I have been unable to reply. You know who you are.)

But the issue. That’s the important thing, what I must focus on. We have writers from around the world — Canada and the U.S. but also Britain, Argentina, Italy, Nigeria, Hungary, Romania, Mexico, Russia, and more. A packed issue. Here’s the rundown.

Wayne Koestenbaum (Credit: Ebru Yildiz)

Wayne Koestenbaum (Credit: Ebru Yildiz)

From Wayne Koestebaum, a writer I’ve know since the mid-1990s when he appeared on the radio show I hosted, we have two stunning “notebooks,” collections of aphorisms, brilliantly witty, mordant and touching (not all at once but delicately threaded).

……………..what is the

Harlequin Romance equivalent of

“friends, Romans, countrymen”?

_________

……………..obtuse

is an ob word like obscene or

oblate or obsequy—

_________

…………………………to stretch

one’s loins across the public domain—

_________

…………………………why

do shrinks even when off-duty

refuse warmth and ebullience?

or do I specialize

in non-ebullient shrinks?

—Wayne Koestenbaum from “#20 [thick book on mother-shelf pinnacled me o’er Tums]”

Chika Onyenezi

Chika Onyenezi

From Nigeria, by the young writer Chika Onyenezi, we have a new story in a mode that combines the contemporary with the folkloric.

A man chopped off a young boy’s head. He lured him to the back of his hotel and butchered him. When they found the head, it had tears in the eyes. That shit was all over the television, the saddest thing I had ever seen. They said he wanted to sell the organs to hospitals in Saudi Arabia. He rotted away in prison. He awaited trial until death took him. I swear everyone wanted to see him hang. The man lived ten blocks away from us before the event. A brave citizen alerted the people when the severed head was discovered at the back of his hotel. Everyone woke up and decided that enough was enough. An angry mob burned his house. For two weeks, smoke still escaped from charred remains. For two weeks, it smelled like a burning foam at his house. Whenever I walked past it, I felt sad. A month later, a bee hive formed. Three months later, a mad man moved into the house. A year later, the children of the murderer came back to claim their father’s property. Madness ruled these streets. Charred insanity rained here. I swear, the street ran itself for a long time. No government authority was effective here. Well, not just the street, the country ran itself, too.

—Chika Onyenezi from “There Are Places God Wouldn’t Go.”

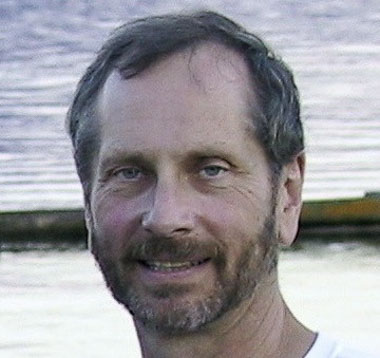

Fernando Sdrigotti

Fernando Sdrigotti

Fernando, one of our indefatigable senior editors, long ago promised me a going-home essay. I never thought I’d get a text as astonishing as this. Fernando flies home to Argentina, and intercut with his own narrative is the fictional narrative of a second homecoming, the two trajectories magically coinciding at the close. This memoir has everything: the myth of return, gritty disenchantment, deft self-analysis and revelation, plus the outreach into fiction, resonance and mystery.

Missing Buenos Aires is a daily routine. Some days the longing arrives after a sound — memories are triggered, homesickness kicks in. Other times it happens after a smell, any smell, heavenly or foul. Most times the longing comes after the wanton recollection of this or that corner, any part of Buenos Aires that in my mind looks like Buenos Aires should look. Some days the feeling is overwhelming and I can spend hours wallowing in self pity. Most times the situation is manageable. I am writing this, listening to Astor Piazzolla, because today is one of those days where I can’t handle homesickness very well. And the music helps with the fantasy, it feeds it.

—Fernando Sdrigotti from “Notes Towards a Return.”

Rikki Ducornet

Rikki Ducornet

Rikki Ducornet — she’s been a comrade and inspiration the past few months. Rikki is one of those too busy to have a piece in the last issue, too burdened with other deadlines. When she told me, I was a tad disappointed. Five days later she sent me a poem, brand new, written for the magazine, a poem with obvious topical resonance framed against the metaphysical, profound with meta-commentary, and yet eruptive, alive.

-One has a tendency to ascribe intention to the Abyss,

……………….even a logical scheme,

although it has been demonstrated, time and time again,

……………….that any given hypothesis, even

“verified” is contingent on provisory facts. As the nursery rhyme asks:

In the mouth of of despot, what is more fickle than facts?

.

Thus is Philosophy forever seated on the horns of chronic uncertainty.

……………….Science, Her Right Hand,

insists that the First Quality of the Abyss is surprise.

—Rikki Ducornet from “Bees Are The Overseers.”

Lance Olsen

Lance Olsen

From Lance Olsen, we have a wonderful section of his novel-in-progress My Red Heaven. In this bit, Walter Benjamin appears seated under a linden tree composing his thoughts toward what will become his epic, unfinished Arcades Project. Readers will want to compare this section with an excerpt we ran earlier from the same novel. The two texts are radically different, and this gives you a sense of the collage structure of the novel as whole. It seems vast and beautiful, gathering the political and philosophical threads of a tortured modernity in early 20th century Europe.

Suppose, he considers, his weak heart twinging, I am falling in love with disjunction. Medieval alleys full of flowers. Suppose I am falling in love with learning to interrupt my —

—Lance Olsen channeling Walter Benjamin, from his novel-in-progress My Red Heaven.

Victoria Best

Victoria Best

Victoria Best said she didn’t have anything but then added that she had been working on a book of biographical essays about writers in crisis (the crisis forged into art). Would I like to see one of those just in case? Sure. She sent me three. I published her essay on Henry Miller in the July issue and saved the one on Doris Lessing for the final issue. It’s a masterpiece. No need to beat about the bush. It’s breathtaking in its concision, its masterful weaving of life event and shrewd psychological analysis and truly perceptive literary reading. Beautiful through and through. (Victoria makes you wonder why anyone would write a 600-page biography.)

Doris Lessing had taken all the ugly, entrapped, rageful relationships she had experienced – her mother and her father, her mother and herself, old Mrs Mitchell and her son, herself and Frank Wisdom, every relationship she had ever witnessed between a white man and his black slave and had distilled the awful essence from them. What she wrote in The Grass Is Singing was that any relationship based on domination and submission was doomed to disaster for all parties concerned; the dominant had to rule so absolutely, the submissives had to be so crushed, that no full humanity was available to either of them. Instead they were locked in airtight roles, waging a futile war to maintain a status quo that damaged and reduced them both. On one side would be fear and contempt, on the other resentment and bitter self-righteousness. Compassion and sympathy – love itself – had no room to breathe, no space to nurture joy and pleasure.

—Victoria Best from “Mother Tongue.”

Doris Lessing

Doris Lessing

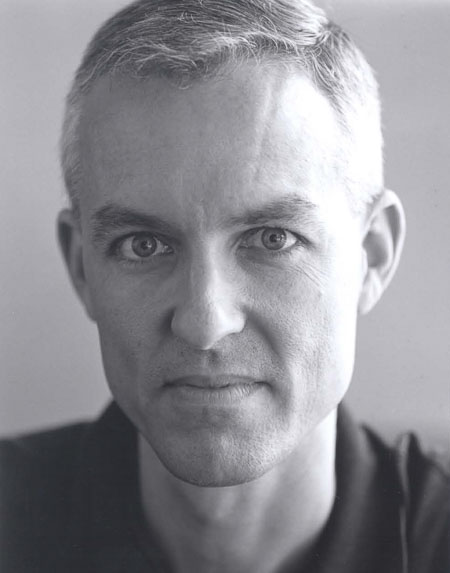

Curtis White

Curtis White

Curtis White heard the call and sent me an excerpt from a work-in-progress written “after Rabelais.” It’s a delicious hoot. You can feel the Rabelaisian rhythms in the sentences. The text revels in excess. And the whole thing sizzles with the ironic tension between the flat American idiom and the ebullient Renaissance syntax. I wrote Curtis back, quoting one of my favourite list sentences from Rabelais, which he immediately recognized as one he used to teach his students.

Having decimated the main courses, she retreated to the soups and polished off one pot each of borscht, split pea, and, soup du jour, potato/leek. (“André! Scratch the soups!”) At this point she observed that her napkin was soiled and asked for another. Pitiless, she ate the herbed caviar roulade, the crepes with caviar filling, potatoes with caviar, caviar éclairs, oysters and caviar, and—a coup de main, de resistance, de theatre, d’etat, de grace, and de foudre—a cobbler with knuckle truffles (the low, obsequious sort common to the Aberdeens), creamed clotters, and crushed sweet-rind. (If you’re looking for the recipe, it’s in Mark Bittman’s Cobblers and Gobblers: Cooking with Cottage Clusters and Custard Clotters.)

—Curtis White after Rabelais from “Dining at the Stockyard Trough.”

S. D. Chrostowska

S. D. Chrostowska

S. D. Chrostowska sent us a mysterious, glittering alternate universe story on the conflict between orality and literacy. The domination of oral cultures by literate cultures is one of my own hobby horses (we’ve both read out McLuhan), so I loved this story. Maybe you’ll want to call it a fable or a parable. But it imagines what would happen if orality were banned entirely.

Of course, much nuance was lost in the process, but it was not mourned for long; the baby, orality, was thrown out with the bathwater of facial expressiveness. Gradually and naturally, even private communication was being conducted exclusively in writing. Writers seen in the act of writing adhered strictly to the no-expression rule, which diverted attention from their face to the text committed on the transparent scroll interposed between interlocutors. Emotional concepts and terms, after a period of proliferation (when they were desperately needed to substitute for previously unconstrained nonverbal expressions), all but vanished as the suppression of expressiveness became normalized. The gestures, habits and practices that underpinned and imbued words like “love” with meaning were gradually lost.

—S. D. Chrostowska from “The Writing on the Wall.”

ZsuZsa Takács

ZsuZsa Takács

From Hungary, we have poems by ZsuZsa Takács translated by Erika Mihálycsa. Takács is the doyenne of Hungarian poetry. We’ve had her in NC before, a short story published last October. And Erika has contributed translations as well as her own essays and fiction. She has been a stalwart for the cause.

Where does bargaining begin, the withdrawal

of consent, the defensive fidgeting, the living

for the last moment, the hour stolen

for banqueting, or making love? I might

lapse there as well – our emperor left the decision to us,

but Socrates forbids cowardly action.

ZsuZsa Takács from “Yearning for an ancient cup” translated by Erika Mihálycsa.

Erika Mihálycsa

Erika Mihálycsa

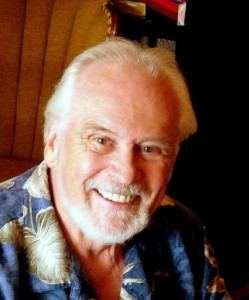

Paul Lindholdt

Paul Lindholdt

Paul Lindholdt submitted a What It’s Like Living Here essay. It was elegant and beautiful. We had a conversation. I said it’s beautiful I’ll publish it but it’s not a WILLH essay because it doesn’t follow the form exactly. He wrote back and said he’d rewrite it. I said don’t you dare rewrite it. He said he wanted it to be a WILLH essay. I said well okay I’ll call it whatever you want as long as I get to publish it. This is where we left things. He’s a tremendous writer.

Col. George Wright hanged members of the Yakama and Spokane tribes. He slaughtered hundreds of their horses to weaken their ability to survive and fight. As a sort of reward his name memorializes a fort, a cemetery and an arterial drive. In turn the most well-known of his victims, Qualchan, lent his name (however ironically) to a real-estate development, a golf course and a footrace.

Onomastics, the study of proper names, has stirred my imagination since I settled here. The name Spokane looks as if it needs to be enunciated like cane at the end. But it has been given a midrange vowel, and so it sounds like can. The creek where Qualchan was hanged appears on state maps as Latah (Salish for fish), but it appears as Hangman on the national records. Federal cartographers seem unwilling to let the state forget its treacherous bit of regional history.

—Paul Lindholdt from his essay “Shrub Steppe, Pothole, Ponderosa Pine.”

Ralph Angel

Ralph Angel

I’ve published Ralph Angel’s poems and his essays before. I thought I’d died and gone to heaven when I read the line: “For the artist, wasting time, which the French perfected, is called discipline.” Need I say more.

For the artist, giving up thinking is called discipline. Giving up hope, giving up certainty, comparison and judgment is called discipline.

For the artist, wasting time, which the French perfected, is called discipline.

“Those who depend upon the intellect are the many,” wrote the minimalist painter, Agnes Martin. “Those who depend upon perception alone are the few.”

—Ralph Angel from “Influence, a Day in the Life.”

Kinga Fabó

Kinga Fabó

Hungary again! Kinga Fabó has already published poems in the magazine, and she’s been a wise and enthusiastic supporter of the magazine for a long time on Facebook and Twitter. Her work is experimental, wildly exciting, slyly ironic, and suffused with a dark eros. For the last issue, she sent me a short story translated by Paul Olchváry.

A fine orgy flooded through her. Perhaps her overblown need for a personality, her oversize ability to attune, was linked to her singular sensitivity to sounds. Effortlessly she assumed the—rhythm of the—other. Only when turning directly its way. She is in sound and she is so as long as she is—as long as she might be. Yet another orgy flooded through her. She would have broken through her own sounds, but a complete commotion?! May nothing happen! “VIRGINITY IS LUXURY, MY VIRGINITY LOOSE HELP ME,” T-shirts once proclaimed. This (grammatically unsound) call to action, which back then was found also on pins, now came to mind. An aftershock of the beat generation. And yet this—still—isn’t why she vibrated.

—Kinga Fabó from “Two Sound Fetishists” translated by Paul Olchváry.

Paul Olchváry

Paul Olchváry

Maria Rivera

Maria Rivera

This is our last Numero Cinco, our Mexican series. Dylan Brennan, our Mexican connections, has curated a powerful activist poem by Maria Rivera called “Los Muertos” and translated for us by Richard Gwyn.

Here come those who were lost in Tamaupilas,

in-laws, neighbours,

the woman they gang raped before killing her,

the man who tried to stop it and received a bullet,

the woman they also raped, who escaped and told the story

comes walking down Broadway,

consoled by the wail of the ambulances,

the hospital doors,

light shining on the waters of the Hudson.

—Maria Rivera, from her poem “Los Muertos” translated by Richard Gwyn.

H. L. Hix

H. L. Hix

Our poetry co-editor Susan Aisenberg has brought back H. L. Hix for our last issue. Long time readers will remember he appeared here once before (look at the poetry contents page). Read these: fitting for the end of things.

Or that the something now coming undone,

much bigger than we are, includes all our

trivial undonenesses in its one

vast undoing, entails that we ourselves are

undone already, no matter what we do,

and undone ultimately, through and through?

—H. L. Hix from “That something has to come undone.”

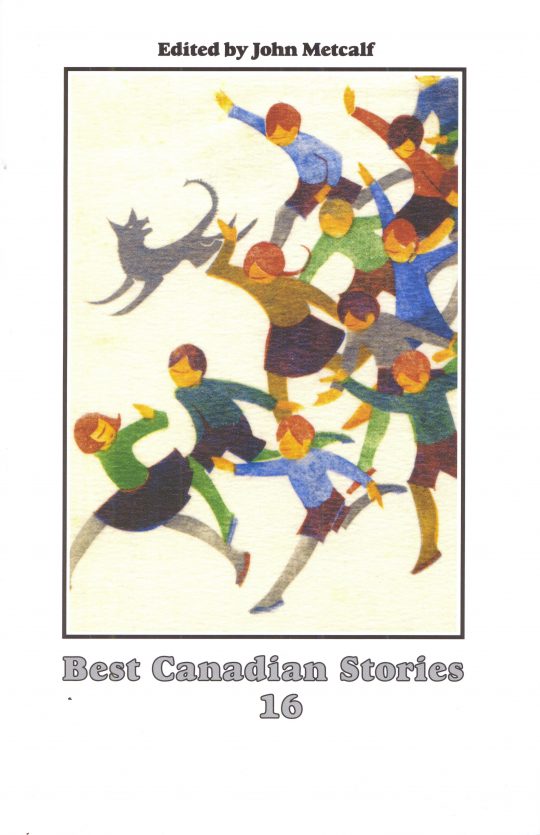

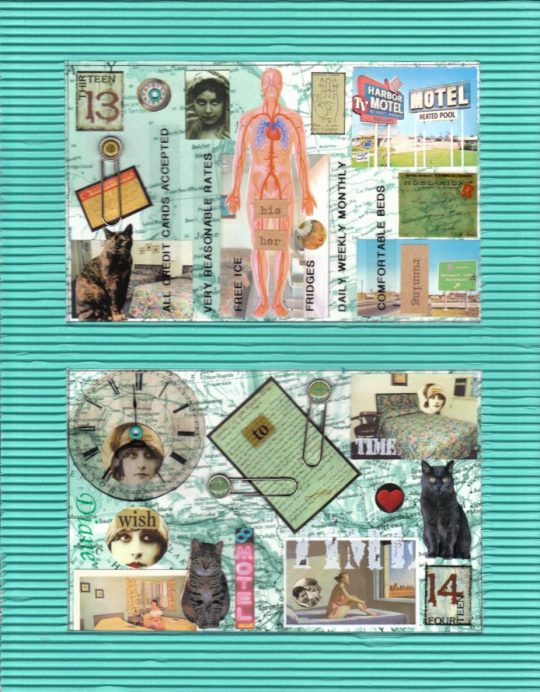

Jowita Bydlowska

Jowita Bydlowska

Jowita Bydlowska just had a story we published selected for the 2017 Best Canadian Stories. I thought we could double that triumph by publishing another story, and she accommodated me. Not only that but she sent along a selection of her gloriously disturbing, alienated photographs as well. I met Jowita years ago when we were both touring for a book. I believed in her and her work from the moment she told me the story of coming to Canada as a young adolescent from Poland, lonely and marginal, and how she assuaged her loneliness by hiding out in the Woodstock, Ontario, public library for days on end painstakingly teaching herself to read English. That’s where she made herself as a writer.

“Why not? She’s beautiful,” my husband says.

She is. I would kiss the redheaded bartender. I’d probably do it for five bucks or for free but I like lying to my husband, pretending to be hesitant about it.

I think he lies to me all the time. I have no proof but if you lie you think everybody else is.

—Jowita Bydlowska from her story “Almost dies all the time.”

Stephanie Bolster

Stephanie Bolster

Ah, the divine Canadian poet Stephanie Bolster who has a talent for opening a chasm in syntax and driving the reader’s car right into it. Brought to us by our poetry co-editor Susan Gillis.

To select different options, click here.

Timed out waiting for a response.

Ten minutes ticking.

If you do not book now, the future into which you would have flown

will be irrevocably erased. No more husband and kiddies

at the park, the little one dangling in the baby swing,

wailing, as big brother tackles the slide for the first time.

Instead you will wait in an airport lounge for a stranger.

You will live on a floodplain and the worst will happen.

A fault will open and your car will plunge.

Earth will fill your mouth.

—Stephanie Bolster from “Midlife.”

Warren Motte

Warren Motte

Warren Motte, through our interactions over the magazine, has become a friend. We exchange news about our sons, our dogs. I solicit work from him, he solicits work from me. We have developed an amiable camaraderie (as I have with many of the writers and editors involved). Warren is also one of the few contributors who truly gets what an NC author photo should look like. I always say, Send me a photo of yourself, preferably relaxed and informal, with a dog or a child. Hardly anyone take me seriously. Only the chosen few who truly understand. Warren is among them.

Odysseus, Panurge, Eugénie Grandet, Gregor Samsa, Humbert Humbert, Oskar Matzerath, all of them from Ahab to Zeno, mere constructs! And their worlds pure figments: no more flying carpets, no more hansom cabs, no more magic lamps, no more tartar steppes! Such a perspective does not bear contemplation for long. Its very bleakness urges us toward another position, I think. One that we can occupy at our leisure, and wherein we are no longer obliged to choose between subject and object, self and other, inside and out.

—Warren Motte from “Division and Multiplication.”

Grant Maierhofer

Grant Maierhofer

Grant Maierhofer just arrived at the magazine last month. We published a Germán Sierra interview with him and a short story. He represents the cutting edge of experimental art that is sometimes called Post-Anthropocene, art that literally comes after the world era of human domination, art characterized by a systematic denial of the sentimentalized anthropocentric view of history and culture. Human have destroyed nature. We are in the countdown (Make America Great Again notwithstanding). I had to get him into the last issue if only because I have a tremendous sympathy for his aesthetic.

Walking for me changed when architecture changed, cities or long rural stretches suddenly took on meaning, became signs of something, warped. In Jarett Kobek’s novel of the 9/11 attacks, ATTA, his iteration of Mohammed, Atta, wanders cities hearing voices in their materials. I hadn’t known this prior to reading but Atta was a student of architecture, had written a dissertation in fact regarding the imperialist dominion of metropolitan architecture over the Middle East. The heft of these sentiments is largely unimportant to my purposes here, but I often wonder about the post-9/11 psyche and its relationship to architecture. Like the possibility of burned, sacked, destroyed works of art—either by the hands of their creators or fascists or mere accident—I wonder if anticipation of destruction alters our sense of the landscape in ways it simply couldn’t prior to the explosive power of our present.

—Grant Maierhofer from “Peripatet.”

Boris Dralyuk

Boris Dralyuk

Boris Dralyuk’s translations of poems by the Russian Alexander Tinyakov come to us via the good offices of Mary Considine Beck to whom we are eternally grateful. And grateful also for these blackly cynical and exuberantly negative poems. Read the teaser quote below. And smile.

Lovely new coffins are headed my way,

full of the finest young men.

Pleasure to see them, simply a joy –

pretty as birches in spring!

—Boris Dralyuk translation, “Joie de Vivre” by Alexander Tinyakov.

A. Anupama

A. Anupama

A. Anupama comes back one last time with a new selection of classic Tamil poetry, beautiful and mystical in their fusing of the erotic and the divine — read them carefully; they are a combination of sly, sometimes comic love poetry and the self meeting the godhead. Go back through the contents pages and read A. Anupama’s own poems, her earlier translations, and her essays on translation. We have a lovely extended archive of her work.

Talaivi says—

We live in the same city, but he avoids my street.

When he does come down my street, he doesn’t step in to visit,

and as though he’s strolling past some strangers’ cremation grounds,

he takes an eyeful and keeps walking,

as though he’s not the one who has driven me out of my shyness

and my mind. Such love, like an arrow shot from a bowstring,

soars for only a moment and falls someplace irretrievable, far away.

Pālai Pādiya Perunkadunkō

Kuruntokai, verse 231

—A. Anupama translation, “Poem from avenues lined with ornamental trees”

Patrick J. Keane

Patrick J. Keane

It took Pat Keane roughly three hours to get me a new essay when I wrote to him. This time an extended treatment of Mark Twain and T. S. Eliot. Erudite, eloquent, lapel-grabbing, astonishing in his ability to access quotations, Pat Keane is like a glacial eccentric, out there on his own, provenance unknown, no other like him. His contributions to the magazine, from early on, have been an anchor to my editorial heart. As long as Pat Keane trusted his work to me, I knew we were doing a good thing.

This recalcitrance of history is often lost in our tendency—not unlike the American love-affair with the film Casablanca—to lavish affection on a book which for many, especially in the wake of Ernest Hemingway’s encomium in the mid-1930s, is the “great American novel.” Placing Huckleberry Finn in the context of longstanding American cultural debates, historicist critic Jonathan Arac registered the virtues of the novel while also pronouncing it mean-spirited. Writing in 1997, he warned against that overloading of the book with cultural value that had led to feel-good white liberal complacency regarding race. And what he called the “hypercanonization” and “idolatry” of Huckleberry Finn was a flaw-forgiving development contributed to, Arac claimed, by Eliot’s Introduction to the novel.

Four years later, Ann Ryan examined Arac’s view that the now iconic Huckleberry Finn has an undeserved reputation as a novel that somehow resolved the issue of racism. In Ryan’s concise synopsis of Arac’s argument, critics since the 1940s, “self-consciously engaged” in an interpretive process, “equated Huck with tolerance and love, Twain with Huck, and America with Twain.” Reacting to the “self-serving criticism” of the “white literary establishment,” Arac represents Huckleberry Finn, not as healing or resolving, but “as a novel with a mean spirit and Twain as an author with a hard heart.” Countering Arac, Ryan argues that “it is precisely this raw quality, in both the book and its author,” that makes Huckleberry Finn a valuable asset in contemporary discussions of race, in general and in the classroom. She argues persuasively that, while Twain “evades political entanglements,” he “intentionally represents this evasion”; and that while the novel clearly “operates on racist assumptions and privileges,” it “unflinchingly illustrates how both are expressed and defended.”

—Patrick J. Keane from his essay “Of Beginnings and Endings: Huck Finn and Tom Eliot.”

Josh Dorman

Josh Dorman

Artist Josh Dorman’s “Tower of Babel” is a gift as cover art for the issue. An updated biblical icon combining a painterly quotation from Breughel the Elder with a Bosch-like menagerie of creatures. I dunno — it does remind me of the magazine in a way. Read the interview and look at other work by Dorman.

I work in a subconscious state. A narrative may assert itself, but more often, multiple narratives and connections emerge. You guessed right when you asked about images that beg to be grouped together. It’s almost as if they’re whispering when the pages turn. It may come from my formalist training or it may be much deeper rooted, but I feel the need to connect forms from different areas of existence. A birdcage and a rib cage. A radiolarian and a diagram of a galaxy. Flower petals and fish scales. Tree branches, nerves, and an aerial map of a river. It’s obviously about shifting scale wildly from inch to inch within the painting. I think the reason I’m a visual artist is because it sounds absurdly simplistic to say in words that all things are connected.

—Josh Dorman

Darran Anderson

Darran Anderson

Fernando Sdrigotti, editor-at-large, snagged this wonderful excerpt from Darran Anderson’s Imaginary Cities. Anderson has long been on my hot list of prospects to invite, so it’s fitting he’s here at the end. Visionary.

The future will be old. It may be bright and shiny, terrible and wonderful but, if we are to be certain of anything, it will be old. It will be built from the reconstructed wreckage of the past and the present and the just-about possible. ‘The future is already here’ according to William Gibson, ‘it’s just not very evenly distributed.’ You sit amongst fragments of it now.

—Darran Anderson from Imaginary Cities.

Montague Kobbé

Montague Kobbé

Montague Kobbé uses To Kill a Mocking Bird as a prospecting tool to help unravel the contemporary mysteries of race, terror, diaspora and transculturalism.

Three days after the fortuitous capture of Salah Abdeslam, Europe’s most wanted man for four months, the BBC published a profile of his lawyer, Sven Mary. The title of the piece was deliberately incendiary and utterly telling of the sentiment prevalent in Paris, in London, in Brussels, in Europe: “Sven Mary: The Scumbag’s Lawyer.”

Despite his notoriety in Belgium as a high-profile defense attorney, I had never before seen a photograph of Sven Mary – indeed, I hadn’t even heard the name until I clicked on the aforementioned piece. Hence, it’s fair to say that I had never really had much of a chance of building a balanced image of the lawyer in question, my judgment necessarily skewed by the tone of the very first notice I had of the existence of this man. This circumstance immediately made me think of Atticus Finch, the hero in Harper Lee’s cult novel To Kill a Mockingbird.

—Montague Kobbé, from his essay “Of Discrimination, Transculturalism and the Case for Integration.”

Michael Carson

Michael Carson

Michael Carson has been on the masthead a short time but he’s already contributed lovely reviews and a powerful essay on story plot. Now, at last, we get to see his fiction. Wild, apocalyptic, dystopian, and alive. Note also his cheeky theft of the double amputation from my story “Tristiana.” Mike confessed when he sent me the story. We have had a good chuckle over this. He’s a young writer I believe in.

But first they have to kill us. It is beautiful from the top of a mountain—the killing. The city glows like it never done from inside. Dark shadows, could be talls, could be dwarves, explode like moths flaring up in candles the size of Jesus. Drones dart in and out of the fire, putting it out with more explosions. Camino Real and a few other hotels crumble. Highway 10 breaks in half. Billy Boy says many cities have done the same. No use getting upset. Billy Boy had some friends of his, Indian tribes come down from Ruidoso, take me up to Franklin Mountain to be safer. He says what’s going to go down no place for a pretty dwarf like me. I say it’s my fault. He says it ain’t no one’s fault. Bound to happen eventually. I say I can fight just like the rest of them. He smiles and says Darling, you a lover, not a fighter. I said he the same. That’s why we in love. But he says, no. He don’t believe in love. We just bugs in the end.

—Michael Carson from “El Paso Free Zone”

Paul Pines

Paul Pines

Paul Pines has contributed visionary and speculative essays and poetry to the magazine, but this time he pens a good old-fashioned memoir that draws on his time running a jazz club in Brooklyn. I adore this essay for its evocation of a place and a time and the music.

My fascination was ignited again during hormonal teenage summers cruising the beach that ran along the southern hem of Brooklyn from the elevated BMT subway stop on Brighton Beach Avenue, all the way to Sea Gate. My crew roamed between the parachute-jump, rising like an Egyptian obelisk from Luna Park, to the fourteen story Half-Moon Hotel. Both loomed like thresholds at the edge of the known world. The haunting quality of the place was especially palpable in the shadow of the Half-Moon Hotel, where Abe Reles, as FBI informant guarded by six detectives, jumped or was pushed out the window on the sixth floor. Reles had already brought down numerous members of Murder Incorporated. His defenestration occurred in 1941, the day before he was scheduled to testify against Albert Anastasia. The hotel’s name echoed that of Henry Hudson’s ship, which had anchored briefly off nearby Gravesend Bay, hoping to find a short cut to Asia. Folded into the sight and smell of warm oiled bodies on the beach and under the boardwalk, past and future pressed hard against the flesh of the present.

—Paul Pines from his memoir “Invisible Ink.”

Bruce Stone

Bruce Stone

From Bruce Stone, an excerpt from a work-in-progress, a trenchant, densely-written fiction. Think: dog boy and sperm trafficker, and a vast, spreading darkness.

If there had been a time before the dogs, the kid couldn’t recall it because, far as he was concerned, ma had always been breeding. He’s still not sure whether dad’s untimely exit was cause or consequence of ma’s decision to surround herself with seedstock Dobermans, but he’s seen the nativity photos of the dogs dipping their muzzles like jailbreak felons into the laundry basket, where the kid lay cushioned on beach towels, that placid dazed expression of a baby contemplating umpteen canine teeth and whiskers stiff as brush bristles. Also inexplicable is how the kid survived infancy when the possibilities for carnage were so numerous and imminent, but here he is, lo these dozen years later, still consuming resources and riding upon the Earth’s surface under the lucky Dog star of his birth.

—Bruce Stone, from his work-in-progress “Tokens.”

Ronna Bloom

Ronna Bloom

From Ronna Bloom in Toronto: tender, intimate poems often set in hospitals, thus bodies, separation, and tenuous hope.

In the Giovanni and Paolo hospital

the old wing opens out like fields and windows

in a Van Gogh painting, light penetrating halls

and making space in silence. No one’s there at all,

but—salve, salve, salve, salve.

When I return to my more brutal realms

the word comes with me. I don’t declare it.

How light in my suitcase it is, how old-fashioned

and almost ethereal, but in some lights

real, and close enough—to salvage.

—Ronna Bloom from “Salve.”

Igiaba Scego

Igiaba Scego

Igiaba Scego is Italian of Somali parentage. We’re privileged to be able to publish this excerpt from the translation of her superb novel Adua.

“Ah, we’ve got a rebel here,” the guard said. “If times were different,” he added, “we would have shown you, you piece of shit. In Regina Coeli we don’t like rebels. You’re ticks, useless lice of humanity. In Regina Coeli it’s easy to die of hunger or thirst, learn that. It’s easy to bring down that cocky crest you’ve got. In Regina Coeli it’s a short path to the graveyard. But you’re a damned lucky louse. They told me not to let you die. So I’ll bring you your water. But mind you, I might not be able to kill you, but put you through hell, that I can do.”

—Igiaba Scego from her novel Adua, translated from Italian by Jamie Richards.

Jamie Richards

Jamie Richards

And as usual there is more still in production. Actually, some not even seen yet but promised. It’s the last issue after all. So come to the bar, place your last orders, enjoy the last hours of conversation and laughter and delight. And say goodbye.

Editor-in-chief, last seen…

Editor-in-chief, last seen…

.

.

Severn Thompson as Elle

Severn Thompson as Elle