Doris Lessing

Doris Lessing

“I think Miller was an early essay and Lessing a much later one, by which point I had grown quite practiced at entering imaginatively into an author’s life (and was probably overconfident about it!). I really loved writing these essays because every writer I chose, once you got down to it, was a hapless flake, making the most terrific mess of their life and yet stalwartly, patiently, relentlessly processing every error, every crisis and turning them all into incredible art. How could you not love these people and their priceless integrity? I felt like I had found my tribe. Didn’t matter in the least that they were pretty much all dead. There was just that precious quality – vital, creative attentiveness to everything wrong – that I cherished.”

1942 in the land that used to be Rhodesia. A 24-year-old mother spreads a picnic blanket out on a lawn beneath the delicate leaves of a cedrillatoona tree. On the blanket she sits her two children: John, a lively three-year-old and Jean, a sweet-tempered baby. They watch their mother with steady interest.

She explains that she is going to have to abandon them.

She wants them to know this is a carefully considered choice. She tells them ‘that they would understand later why I had left. I was going to change this ugly world, they would live in a beautiful, perfect world where there would be no race hatred, injustice, and so forth.’

Her comrades in the Rhodesian branch of the Communist party have been encouraging her for several months now to break away from her family. For the first time in her life, the young woman feels solidarity in her aims and her principles; the group has given her both strength and freedom to take this extraordinary step. But it is not really – or at least not wholly – politics that has provoked it.

‘Much more, and more important: I carried, like a defective gene, a kind of doom of fatality, which would trap [the children] as it had me, if I stayed. Leaving, I would break some ancient chain of repetition. One day they would thank me for it.’

The children, she believes, are the only ones who ‘really understood me’, unlike her husband, who is bewildered and shocked by her decision, and her mother, ever a stern critic and now in possession of a righteous rage. ‘Perhaps it is not possible to abandon one’s children without moral and mental contortions,’ the young mother would later write. ‘But I was not exactly abandoning mine to an early death. Our house was full of concerned and loving people, and the children would be admirably looked after – much better than by me.’ In her own mind, her act was one of desperate self-rescue. ‘I would not have survived. A nervous breakdown would have been the least of it… I would have become an alcoholic, I am pretty sure. I would have had to live at odds with myself, riven, hating what I was part of, for years.’

The young woman went on to become Doris Lessing, author of 27 novels, seventeen short story collections, numerous non-fiction works, and winner of the Nobel prize for literature. But when she left her children she had scarcely begun to write. She was Doris Wisdom, a bored and miserable housewife, irritated by her husband, ambivalent towards her babies, and terrified of repeating the strains and traumas of her parents’ marriage. All she had was her literary ambition and a hatred for the inequalities of the country she grew up in, which was almost as fierce as her love of the land.

From these disparate ingredients she would produce a first novel of raw, corruscating power, a novel that would take London by storm when she arrived with the manuscript in her suitcase, and inform a colonising power of the desperate abuses that took place on either side of the colour bar.

But before she left Rhodesia, she was going to make the same mistakes of marriage and motherhood all over again.

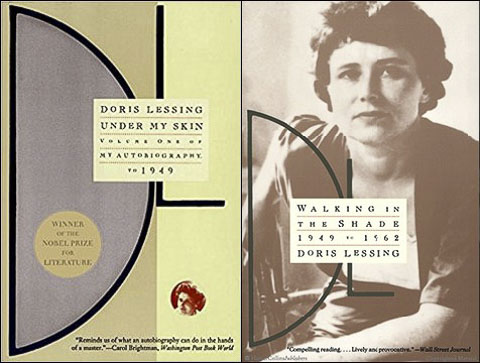

Doris Lessing with 2007 Nobel Prize in Literature

Doris Lessing with 2007 Nobel Prize in Literature

***

Doris Lessing was born in 1919 to the dispirited aftermath of the First World War. Her parents met in the Royal Free Hospital in East London. Doris’s mother was Sister Emily MacVeigh, the clever but unhappy daughter of a disciplinarian father. Doris’s father, Alfred Tayler, had lost a leg, his optimistic resilience and half his mind in the trenches. While Emily nursed him, the doctor she intended to marry went down with his ship. Neither could have the life they wanted, and so they determined to make do with the shared burden of their disappointments. Alfred married in order to make restitution to the woman who had saved his life and his sanity, whom he knew wanted children. Emily did indeed want children, but marriage meant she had to refuse the offer of a matronship at St George’s, a famous teaching hospital, which would have been a fine post for a woman in her era. She did not do so without inner turmoil. And then, depressed and shell-shocked still, Alfred Tayler was insulted to the core when handed the white feather of cowardice by a group of women in the street who could not see the wooden leg under his trousers. Unable to tolerate his feeling that his own country had betrayed him, he took a post in a bank in Persia.

Lessing’s parents, Alfred Tayler and Emily McVeigh

Lessing’s parents, Alfred Tayler and Emily McVeigh

Doris Lessing believed that her mother was as depressed as her father, conflicted over the choices she had made, the sudden emigration, and the weariness of having worked so hard in the war. As a couple they had been advised not to have children too soon, but Emily was already thirty-five and may not have wanted to wait. They joked that she fell pregnant on their wedding night. In Persia, after a difficult forceps birth, she was handed not the son they wanted, but a daughter for whom they didn’t even have a name. The doctor suggested Doris. ‘Do I believe this difficult birth scarred me?’ Lessing would later write in her memoirs. ‘I do know that to be born in the year 1919 when half of Europe was a graveyard, and people were dying in millions all over the world – that was important.’

The early years in Persia were, in fact, to be some of the happiest her parents would know. On arrival, it was as if they sloughed off old identities, her mother taking on her middle name ‘Maude’ and renaming her father ‘Michael’, which she felt sounded classier. Maude loved the rounds of colonial parties with the ‘right sort’ of people, her husband was content at the bank, and another baby arrived, the much hoped-for son. Doris Lessing’s earliest memories were of slouching against her father’s wooden leg in social gatherings, hearing herself relentlessly discussed by her mother: how difficult and naughty she was, how she made her mother’s life a misery. Her baby brother, by contrast, was perfect. To the cross, elderly nursemaid who ruled the children’s lives, Maude would say ‘Bébé is my child, madame. Doris is not my child. Doris is your child. But Bébé is mine.’ It was a psychologically unsophisticated age, in which childcare was dominated by the strictures of Truby King, who advocated strict discipline in the nursery. Lessing never forgot her mother’s gleefully recounted tales of how she had nearly starved her daughter on a rigid three-hour feeding regime that failed to take into account the thinness of Persian milk. Doris and her brother were potty trained from birth, held over the pot for hours each day. ‘You were clean by the time you were a month old!’ Lessing remembers her mother saying, though she did not believe it. Nor did she believe her mother’s romantic expressions of love as the basis of her mothering. ‘The trouble is, love is a word that has to be filled with an experience of love. What I remember is hard, bundling hands, impatient arms and her voice telling me over and over again that she had not wanted a girl’. Doris’s birth had been inauspicious, and now her upbringing was proving catastrophic. ‘The fact was, my early childhood made me one of the walking wounded for years,’ she wrote. ‘I think that some psychological pressures, and even well-meant ones, are as damaging as physical hurt.’

In 1924 their time in Persia ended, but after a few months in an England that felt as depressing as ever to the Taylers, Michael went to the Empire Exhibition and was seduced by the thought of farming in Southern Rhodesia. With ill-prepared impulsiveness they sailed to Cape Town (though they both had all their teeth removed on the unsound advice that there were no dentists in Rhodesia). Michael was laid low with seasickness and remained in the cabin for most of the journey, whilst Maude had a wonderful time consorting with the Captain, regardless of the rough weather. They enjoyed ‘hearty jollity’ together and Doris found to her discomfort that the Captain was a keen practical joker. He told her one day she must sit on a cushion ‘where he had placed an egg, swearing it wouldn’t break… My mother said I must be a good sport.’ Doris was wearing her party dress, which was spoiled, and the Captain roared with laughter. There was worse to come. ‘When we crossed the Line I was thrown in, though I could not swim, and was fished out by a sailor. This kind of thing went on, and I was permanently angry and had nightmares.’ Looking back, she did not believe her mother was a naturally cruel person; she was simply grasping at a good time with both hands, drunk on pleasure and anticipation, falling in with the ‘done thing’ on board. But for Doris, it was an early, wounding lesson in how those in control could so lightly and easily humiliate others, barely noticing what they did.

By the time they arrived at the Cape, Doris was starting to steal things and to lie. ‘There were storms of miserable hot rage, like being burned alive by hatred.’ She took a pair of scissors, thinking she might be able to stab her much-disliked nursemaid, Biddy, with them. Then a sudden and unexpected balm to her spirits: for five days and nights they travelled in an ox wagon, leaving behind the niceties of home – Liberty curtains, trunks of clothes, silver tableware, Persian carpets and a piano – to follow on later by train. For Doris, bumping along the rough track into a vast emptiness ‘there is only one memory, not of unhappiness and anger, but the beginnings of a different landscape.’ Her impressionable sensitivity was being given a new world to work on. The spiralling horns of a koodoo, the glistening green slither of a snake, anthills for shade, beetles and chameleons, thick red soil churned by the monsoon rains. It was a landscape to echo the intensities and vastness of her misunderstood emotions, a harsh landscape for sure, but one of overwhelming beauty.

Her parents had chosen a grand hilltop site for their home, but they could only afford to construct a traditional mud house with a thatched roof upon it. It contained both the piano and furniture fashioned out of petrol boxes, the Liberty curtains and bedspreads made of dyed flour sacks. There were no ‘nice’ people in the district, to Maude’s despair. She had had dresses made for entertaining, calling cards printed, bought gloves and hats that she would never wear. Instead of the glamorous life she imagined, she had a toilet that was a packing case with a hole in it over a twenty-foot drop. The farm was too big for a man with a wooden leg, but too small to make any profit. The heat was crippling. They all had malaria. Twice. Maude took to her bed for a year with a ‘bad heart’, enraging Doris with unwanted, burdensome pity for what she understood even then to be depression.

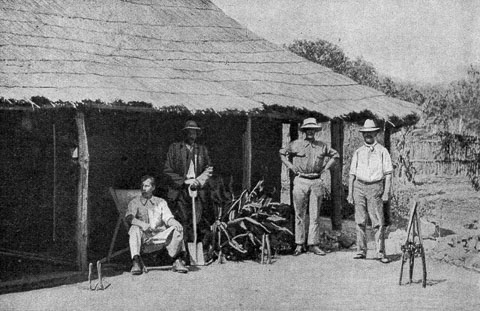

Settler farm in Southern Rhodesia, early 1920s, via Wikimedia Commons

Settler farm in Southern Rhodesia, early 1920s, via Wikimedia Commons

Maude’s illness brought Mrs Mitchell and her son into their lives, supposed to act as ‘help’. Doris experienced them as another chip of nightmare, the woman a heavy drinker and her son a bully. Writing about them in her memoir, she realised they came from the extreme end of white poverty, from a life she could not have imagined as a child, and which the immigrant farmers around them never wanted to acknowledge as a depth to which whites could sink. Mrs Mitchell and her son roundly abused the black workers, and decried Michael Tayler’s attempts to treat them well. It was, Lessing remembered, the first encounter she had with the ugly white clichés. ‘They only understand the stick. They are nothing but savages. They are just down from the trees. You have to keep them in their place.’ The Mitchells left after a few months and Doris and her brother took to joining their father down on the land. Eventually Maude rose from her bed, having decided it was the weight of her hair that was giving her headaches. She cut it all off, reducing her children to tears as they rolled in shanks of it on the bed, then she bundled it up, threw it in the rubbish pit and set to work.

Lessing with her mother and brother

Lessing with her mother and brother

***

Doris was eight years old when she was first sent away to the Roman Catholic Convent. The main subject was fear. The dormitories held grisly images of the tortured Saint Sebastian, the broken, crucified Jesus, whose swollen heart disgorged gouts of blood. At bedtime, one of the nuns would stand in the doorway and tell them: ‘God knows what you are thinking. God knows the evil in your hearts. You are wicked children, disobedient to God and to the good sisters who look after you for the glory of God. If you die tonight you will go to hell and there you will burn in the flames of hell’. They were allowed a bath once a week and were supposed to wear boards around their necks that prevented them from seeing their own bodies. In her memoirs, Lessing calls the atmosphere ‘unwholesome’, a notable understatement. Her parents’ attitude towards her was disquieting and she had a dawning sense that all was not right for the blacks on the farm. But this must have been her most clear and immediate experience of abuse by authority. She had never known power except self-indulgent or corrupt.

When a bad kidney ailment brought Doris into the sickroom and the care of one of the few kindly nuns, she found a power of her own in illness. It was a button she could push that made her mother jump, and she pushed it repeatedly. Lice and ringworm would sign her release papers from the nuns. At the next boarding school, measles gave six weeks of blessed quarantine and then a bad eye infection – violent to look at but not serious – set her free. She insisted she could no longer see properly, and made her mother take her home.

And so, at fourteen, Doris finished her meagre education and gave her full attention to the covert cold war with her mother. ‘I was in nervous flight from her ever since I can remember anything and from the age of fourteen I set myself obdurately against her in a kind of inner emigration from everything she represented,’ she wrote in her memoirs. When she returned to the farm, it was to a new level of her mother’s intrusive care. Her father had diabetes by now and had entered a long, slow decline that cemented his general air of helplessness. Maude nursed him with obsessive attention, and extended her compulsive care to her daughter, fretting over what she ate, and worrying about her going alone in the bush. It was not love that provoked this behaviour, Doris believed, but a struggle over control. For the biggest argument between them was over clothes: her mother wanted her to wear smart, frilly dresses, entirely inappropriate for her age and surroundings. ‘I knew what it was my mother wanted when she nagged and accused me, continually holding out these well-brought-up little girls’ clothes at me. “Well try it on at least!” They were sizes too small for me.’ When Doris sewed herself her first bra, her mother noticed, called for her father, and then whipped her dress up over her head so he should see it. ‘“Lord, I thought it was something serious,”’ her father grumbled, edging away.

Doris Lessing, age 14

Doris Lessing, age 14

Both Doris and her father hated the way she treated the black servants, always talking to them in a ‘scolding, insistent, nagging voice full of dislike’. ‘“But they’re just hopeless, hopeless,”’ she would wail when confronted. The ‘Native Question’ had become a topic of hot debate between Doris and her parents. ‘I had no ammunition in the way of facts and figures, nothing but a vague but strong feeling that there was something terribly wrong with the System.’ She read letters in the Rhodesia Herald, arguing that the black workers were inefficient because they were housed and fed so badly, and Doris felt ashamed at how little they were paid on her own farm. But such opinions felt vague against the pervasive conviction that blacks were simply lazy and stupid. Her father was kinder in his views but he was as ineffectual against her mother’s virulent opinions as he was in everything else. Small wonder that Doris was determined to escape, physically, mentally and emotionally.

Doris had already created a false self, a kind of persona she could hide behind in an attempt to keep her mother out of the private parts of her mind. She had early realised that ‘it was [my mother’s] misfortune to have an over-sensitive, always observant and judging, battling, impressionable, hungry-for-love child. With not one, but several, skins too few.’ After a bout of family enthusiasm for A.A. Milne when she was a child, Doris began to live up to her nickname of ‘Tigger’. Tigger Tayler was a daughter in her mother’s image, capable and resilient with brutal good humour, a good sport with a thick skin. At 18, she heard there were jobs to be had at the telephone exchange in Salisbury and moved there, mastering the easy work by day and joining in with the party crowd at night. Tigger Tayler was all about love and excitement, proud of her strong, beautiful young body. She smoked, she drank, she danced – and was a good dancer. It was 1938 and she knew, as everyone did around her, that war was coming. Tigger dreamt of becoming an ambulance driver, a spy, a parachutist, whilst throwing back the cocktails and losing herself to the rhythms of the music. The adventure she actually chose would be the most mundane on offer.

‘A young woman sensitised by music, and every molecule simpering in abased response to the drums of war, a young woman in love with her own body – she did not have a chance of escaping her fate, which was the same as all young women at that time,’ Lessing would write in determined self-absolution in her memoir. Tigger Tayler with her gung-ho attitude and smouldering sexuality had found a way to coincide with the lost, lonely, hungry-for-love child she was trying to cover up, although she would describe her reckless rush into marriage as happening under the effects of ‘the same numbness, a kind of chloroform, that overtakes someone being eaten by a lion.’

And so it was that, at 19, she returned to the farm with a fiancé in tow to introduce to her parents. He was Frank Wisdom, a civil servant – a respectable profession for which her parents were grateful, though they assumed Doris was pregnant. In fact she was, but didn’t know it at the time. They had a ‘graceless wedding,’ which in retrospect she claimed to have hated: ‘It was “Tigger” who was getting married.’ And then there were two children born in quick succession: a demanding and hyperactive boy, John, and a sweet, affectionate girl, Jean. For a few years, she played at the conventional role of housewife and did so with competence and much inner anguish. ‘There is no boredom like that of an intelligent young woman who spends all day with a very young child,’ she wrote. She was perpetually exhausted, partly from the demands of the children, partly from the pretence of being Tigger, partly from suppressed rage at her mother who now visited regularly and criticized her decisions, often calling her selfish and irresponsible in a way that must have utterly infuriated her, given her own memories of childhood.

Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia, 1930 via Wikimedia Commons

Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia, 1930 via Wikimedia Commons

Frank did not understand why Doris took to bed, weeping with fury, once she had gone. But then Frank and Doris had quickly grown apart. The war was on, but Frank had been turned down for active duty on medical grounds. He nursed his resentment and shame over too many drinks at the club. He agreed that Doris would write when she had the time and energy, but he grew angry when the poetry she produced was fiercely critical of apartheid, afraid it might undermine him in his job. She would become increasingly involved with subversive organisations, and he would become a cliché of conventionality.

Not long after Jean was born, Doris made the decision to take a month off and travel to Cape Town with John. Her health had been suffering; she was tired all the time and had fainting fits. ‘I was miserable and confused, being torn apart by these two babes,’ she wrote. The demanding task of caring for two small children was complicated by an unformed, unarticulated sense of profound self-betrayal. A neighbour, who, according to Lessing, had longed for a daughter all her life, was lined up to take baby Jean. ‘I did not feel guilty about this then, and do not feel guilty now,’ she wrote. ‘Small babies need to be dandled, cuddled, held, comforted and it does not have to be the mother.’ This was to be a formative month, in which she met, at the boarding house where she was staying, a woman from a Christian organisation promoting good race relations by way of the sort of straight talking that hypnotised Doris. ‘“How can one describe a country where 100,000 white people use 1 million blacks as servants and cheap labour, refuse them education and training, all the time in the name of Christianity?”’ she asked, and Doris found it a ‘revelation’.

She returned home rested, revolutionized and newly inspired to write. Frank agreed help was needed and it was a sign of the times that a mother leaving her child for a month never raised an eyebrow, whereas hiring a black nanny and inviting her to live in the house was cause for scandal. Doris’s mother even ambushed Frank in his office to express her outrage. The nanny had to go, and Doris’s political and personal claustrophobia worsened.

It was at this time that she joined the Communist group that would have such an influence; Communist, socialist, progressive, these were very blurred lines at the time for her, but she knew for sure that her attitude marked her out pejoratively. ‘All over Southern Rhodesia were scattered people whose attitude toward race would be commonplace in a couple of decades, but now they were misfits, eccentrics, traitors, kaffir-lovers.’ The persona of Tigger Tayler – briefly Tigger Wisdom – was finally breaking down, under sustained assault by subversive political ideas and her suppressed rage and resentment. She was destroying her energy with domesticity, when she could be doing something of vital good to the world. Her situation was chaotic, messy, emotionally distraught. Frank hated her politics but didn’t want her to leave. Doris felt she hated him – because she was treating him so badly. She was desperate to be free. The holiday she had taken now turned out to be a rehearsal for something altogether more audacious, and her new political friends encouraged her. Those years behind the false self had left her feeling she was a stranger to herself and she could not bear it. Nor could she tolerate the ‘terrible provincialism and narrowness of the life.’ She knew that if she left she would be doing something ‘unforgiveable’.

She left anyway.

***

Doris Wisdom abandoned one family in 1942. In 1943 she married again, this time a man whom she didn’t much like even when she married him. Gottfried Lessing was a committed Communist, a hard-working lawyer, a German intellectual and, in Doris’s eyes, a cold, humourless soul. But they had met through the Rhodesian Communist group and he was at least a match for her politically. ‘It was my revolutionary duty to marry him,’ Doris wrote. Gottfried felt it would increase his chances of obtaining British nationality, for both he and Doris now longed to escape South Africa for England, and he believed that marriage would protect him from the threat of the internment camp, where his political interests could still land him. But what was really going on? Why would Doris, even out of a misplaced sense of duty, rush back into marriage with such impetuous self-abandon? She would claim it was because the marriage was a sham, just a matter of convenience, but it seemed as if she needed the impetuosity and the thoughtlessness to whitewash a deeper, more shameful need.

She was struggling hard to find out who she was. After leaving her husband and children she fell ill for a long time because, she believed, ‘I was full of division.’ The Communist group that she had placed so much faith in was not providing her with the certainties she hoped it would, for it had swiftly ‘dwindle[d] into debate and speculation. We were too diverse, there was too much potential for schism.’ Doris’s family were ever more horrified by her political engagements and her messy personal life. And her sex life with Gottfried was a disaster. But one positive change had been effected: she had finally started to write with commitment – the first draft of a serious novel about the deep inequalities that wracked her country and had spoiled her early life. Division might have been destroying her, but it would be translated with power and beauty into her writing.

Then, as if in sabotage of this step in the right direction, around Christmas 1945 Doris fell pregnant again. She and Gottfried had to be married for a while, so they might as well ‘fit in’ a child, they told their friends, ‘we’ve got nothing better to do.’ Her parents were horrified. ‘My father said: “Why leave two babies and then have another?” My mother was fiercely, miserably accusing.’ Lessing’s own explanation was casual and bizarre. ‘I believe it was Mother Nature making up for the millions of the dead… Besides, I wanted another baby. I yearned for one.’ Doris was at the mercy of her own poorly understood compulsions, and more so than ever as she tried to find her authentic self. But maybe her instincts, or the experience of thinking and writing seriously about the inequalities of power, were covertly working on her side, for when baby Peter was born, something seemed to click into place. Now having a baby was ‘easy going and pleasant.’ ‘I was in love with this baby,’ she wrote in her memoir, in a way that seems a thoughtless judgement on her abandoned children. One thing seemed to make a huge difference: she had discovered Dr Spock and the idea of feeding on demand. Her mother’s insistence on the timed feeds of Truby King had felt wrong and punitive to her when nursing her first two babies. Now she fed this one on demand, to her mother’s outrage, to her own exquisite relief. Now feeding was a dialogue with her child, not an act of oppression.

Finally at the end of 1948 the official papers arrived, permitting Doris and Gottfried to leave South Africa for England and the decision was made that Doris would sail to London ahead with Peter. In her suitcase she carried the manuscript of the novel that she had worked on in fragmented and frustrated fashion, between the demands of her baby, her mother, and her wide circle of political acquaintances. She hoped it would make her name.

What she did not know, in her elated escape to London, was that she was heading for a decade of single motherhood. Of all her situations, this one might seem on paper the worst of them all, scraping a living by writing whilst bringing up a son alone. But later she would claim this child had saved her. Although she finally sent Peter to boarding school aged twelve, those interim years saw her stuck to her writing from sheer necessity. She could not go out and party and find new lovers and make more disastrous marriages. She was obliged to commit to work, despite fatigue and loneliness. It is not certain whether Peter had the kind of mother that textbooks idealise, but it was these years of hard apprenticeship that transformed Doris Lessing from a natural talent to a phenomenally successful writer.

***

When she arrived in London, Doris Lessing sold the manuscript of her first novel quickly and easily to the publishing house Michael Joseph. The Grass Is Singing was the novel that had been written as she searched long and hard for her sense of a true self, that came out of the mire of hatred and resentment at the injustices she had suffered as a powerless child, and which she saw mirrored in the cruel country around her, where native ‘children’ were oppressed by a harsh and loveless white authority. In that shared suffering she had found her story—though the great audacity of her novel was to speak of racial prejudice in the voice of the white oppressor, to make the ugliness and the injustice of the colour bar stand out starkly.

Cover and author photo from first British edition of The Grass is Singing, via dorislessing.org

Cover and author photo from first British edition of The Grass is Singing, via dorislessing.org

She had been warned over and over as a child against the dangers of black men and one true story had stuck in her mind: in Lomagundi, a white woman had been brutally murdered by her black servant. That memory provided the opening of her story: a (fictional) notice in a newspaper of the death of Mary Turner, a white farmer’s wife at the hand of her manservant, Moses. The opening chapter takes place in the shocked aftermath of the discovery of Mary’s slaughtered body by Tony Marsden, a recent arrival at the farm who is learning the ropes of colonial stewardship. Tony is dumbfounded by the attitude of the other men on the scene: the police sergeant and Charlie Slatter, the nearest neighbour and a farmer of the rich, efficient and brutal kind. The two men have more contempt for the victim than for the killer, for after all, a black man will always kill if suitably provoked. Tony wants to tell them the truth of the situation as he sees it: that Moses and Mary Turner had a strangely close and complicit relationship. But he comes to realise ‘in the silences between the words’ that he must never give voice to his testimony, because it opens up possibilities that cannot be held in the colonial mind. He understands his own social survival is at stake: ‘He would have to adapt himself, and if he did not conform, would be rejected: the issue was clear to him, he had heard the phrase “getting used to our ideas” too often to have any illusions on the point.’ And so it is understood that Mary nagged her servant and he killed her for it. The rest of the novel returns to the beginning of Mary’s story to reveal the unspeakable, complex truth.

Mary is an indigenous white whose parents belonged to the lowest echelons, her father a harmless, useless drunk and her mother a bitter woman who treats her husband with ‘cold indifference’ when alone and ‘scornful ridicule’ in the presence of her friends. Mary is pulled into her mother’s orbit as her unwilling confidante and escapes home at 16, as Doris did, to an office job in town. Here she lives mindlessly and contentedly in a sort of arrested development, feeling only relief when her parents die, until one day in her 30s when she overhears the unkind gossip of her friends at a party. They poke fun at her girlish clothes and make snide remarks about her unmarried status, and she is distraught: ‘Mary’s idea of herself was destroyed and she was not fitted to recreate herself…She felt as she had never done before; she was hollow inside, empty, and into this emptiness would sweep from nowhere a vast panic’. It is enough to propel her into the arms of the first available man. He happens to be Dick Turner, a cautious, uneasy man who dislikes the town and only feels comfortable on his beloved veld. For years he has been farming in a small, unprofitable way, loving his land and managing nothing more than meagre self-sufficiency. It has recently occurred to him that a woman about the place might be nice; someone to comfort and support him, and to boost his wavering morale.

What follows is the slow, painful and inexorable failure of their marriage. Mary is left to fend for herself in a tin-roofed shack, prostrated by the heat and half-dead from boredom. Dick, meanwhile, fritters their money away on overly optimistic schemes – pigs, turkeys, rabbits, all of which fail gently. Dick longs for love but is too isolated in himself, too caught up in his own foolish schemes and ventures to give Mary what she needs to be happy. Mary can’t assert herself against his implacable small-mindedness, her energy ebbing away as she realises she is stuck in a situation designed to drive her crazy. It is all too like her hated childhood, and their relationship starts to mirror that of her parents. For Mary is capable and intelligent; if she believed there were any happiness to be had she would work hard for it. Instead her feelings for Dick drift towards fury and contempt, which she then has to work hard to subdue because it is unbearable to admit they are wrong for each other and lack the ability to change.

Mary’s emotions are vented on the succession of black servants in her household without her even fully realising it. She is enraged by their neutral submissiveness, which she reads as shifty dishonesty, finding in the lack of relation between them an uncomfortable analogy to her marriage with Dick. The servant is ‘only a black body ready to do her bidding’ which angers her even more. When Dick falls ill with malaria she is obliged to oversee the men on the farm and the experience turns her into a vicious bully – her fear and insecurity, her frustration and claustrophobia channelled into an acceptable outlet. When one man insists on fetching himself a drink she brings her whip down on his face rather than bear his disobedience, and several months later she is horrified when Dick brings the same man to the house as their new servant.

Mary and Moses now begin a psychological dance to the death around each other. The scar of the wound she inflicted reminds Mary inexorably of her mistreatment of Moses, a crime she cannot admit to herself for then she would have to unpick a whole series of feelings that lead to even more unbearable truths. And so her anger and her violence turn inwards instead and she becomes terrified of him. Moses is aware of this and his blank, neutral servitude becomes tinged with other emotions – curiosity, contempt, his own unresolved anger. As their situation intensifies Mary’s ‘feeling was one of a strong and irrational fear, a deep uneasiness and even – though this she did not know, would have died rather than acknowledge – of some dark attraction.’ Mary gives up the fight in her own mind and the narrative shifts to a different perspective. Now we catch glimpses of her allowing Moses to help her into bed for her rest, and buttoning her dress when she gets up again. Whatever their relationship, it is untenable. Unable to tolerate the situation any longer, Mary sends Moses away, knowing he will return to kill her.

Doris Lessing had taken all the ugly, entrapped, rageful relationships she had experienced – her mother and her father, her mother and herself, old Mrs Mitchell and her son, herself and Frank Wisdom, every relationship she had ever witnessed between a white man and his black slave and had distilled the awful essence from them. What she wrote in The Grass Is Singing was that any relationship based on domination and submission was doomed to disaster for all parties concerned; the dominant had to rule so absolutely, the submissives had to be so crushed, that no full humanity was available to either of them. Instead they were locked in airtight roles, waging a futile war to maintain a status quo that damaged and reduced them both. On one side would be fear and contempt, on the other resentment and bitter self-righteousness. Compassion and sympathy – love itself – had no room to breathe, no space to nurture joy and pleasure. The complex reality of the individual was lost, and in the absence of that true self, perversity set in. She had witnessed it and she had lived it, over and again. She had come to understand that thwarted people lived stubbornly in self-division, pleading with others for the things they didn’t want, setting their faces obdurately against the things they did. Her unholy triangle of Mary and Dick Turner and their houseboy, Moses, provided a graphic, psychologically brilliant diagram for how the catastrophe took place.

Doris Lessing would go on to write more detailed autobiographical novels about her upbringing and early marriages in Africa, but this was the one she wrote as she waited impatiently to leave behind everything that was hopelessly wrong about her life. It was the one she wrote as she struggled to put her false self behind her and find a way of being that corresponded more accurately to her genuine desires. For the rest of her life she could be shockingly lacking in self-awareness when it suited her; it was a strategy that she never abandoned for its usefulness was too great. But when she wrote this first novel she was trying most sincerely to be as truthful as she knew how. She had done ‘unforgivable’ things in order to win herself that freedom. And in the shift from one family to another, in that new relationship she forged with her third child, she did seem to break free from the tyranny of motherhood that had haunted her for so long. Right back at its origins, the imbalance of power began at the mother’s breast, and the consequences could be seen in the colonised nations. She believed she could mother differently to her own mother, and in doing so she would break a vital chain – the figurative chain that kept all slaves in their place.

x

x

x

Notes on Sources

All the biographical material in this essay is drawn from Lessing’s two magnificent volumes of autobiography, Under My Skin (1994) and Walking in the Shade (1997). The story I have picked out here represents a tiny fraction of the wealth of incident and insight that the books contain, for they are, as one might expect from her, wonderfully wide-ranging, brutally honest and suggestively rich. I warmly recommend them.

—Victoria Best

x

x

Victoria Best taught at St John’s College, Cambridge for 13 years. Her books include: Critical Subjectivities; Identity and Narrative in the work of Colette and Marguerite Duras (2000), An Introduction to Twentieth Century French Literature (2002) and, with Martin Crowley, The New Pornographies; Explicit Sex in Recent French Fiction and Film (2007). A freelance writer since 2012, she has published essays in Cerise Press and Open Letters Monthly and is currently writing a book on crisis and creativity. She is also co-editor of the quarterly review magazine Shiny New Books. http://shinynewbooks.co.uk

x

x

Luna Park by Marc Shanker

Luna Park by Marc Shanker Tin Palace entrance by Ray Ross

Tin Palace entrance by Ray Ross Apollo pouring a libation to a blackbird

Apollo pouring a libation to a blackbird Cornelia Street 1922 by John Sloan

Cornelia Street 1922 by John Sloan Angel: New Orleans by Paul Pines

Angel: New Orleans by Paul Pines Outside the Tin Palace, 1976 (courtesy Patricia Spears Jones) clockwise: Stanley Crouch, Alice Norris, David Murray, Carlos Figueroa, Patricia Spears Jones, Phillip Wilson, Victor Rosa and Charles “Bobo” Shaw

Outside the Tin Palace, 1976 (courtesy Patricia Spears Jones) clockwise: Stanley Crouch, Alice Norris, David Murray, Carlos Figueroa, Patricia Spears Jones, Phillip Wilson, Victor Rosa and Charles “Bobo” Shaw Paul Blackburn by R.B. Kitaj

Paul Blackburn by R.B. Kitaj

Nephin mountain

Nephin mountain  Amanda Bell and daughter near the summit of Mount Nephin

Amanda Bell and daughter near the summit of Mount Nephin Author 1971 or 1972

Author 1971 or 1972  The author at Pontoon, 1972

The author at Pontoon, 1972 Author’s grandfather and brother collecting turf

Author’s grandfather and brother collecting turf The author and her brother

The author and her brother Mayo Road

Mayo Road

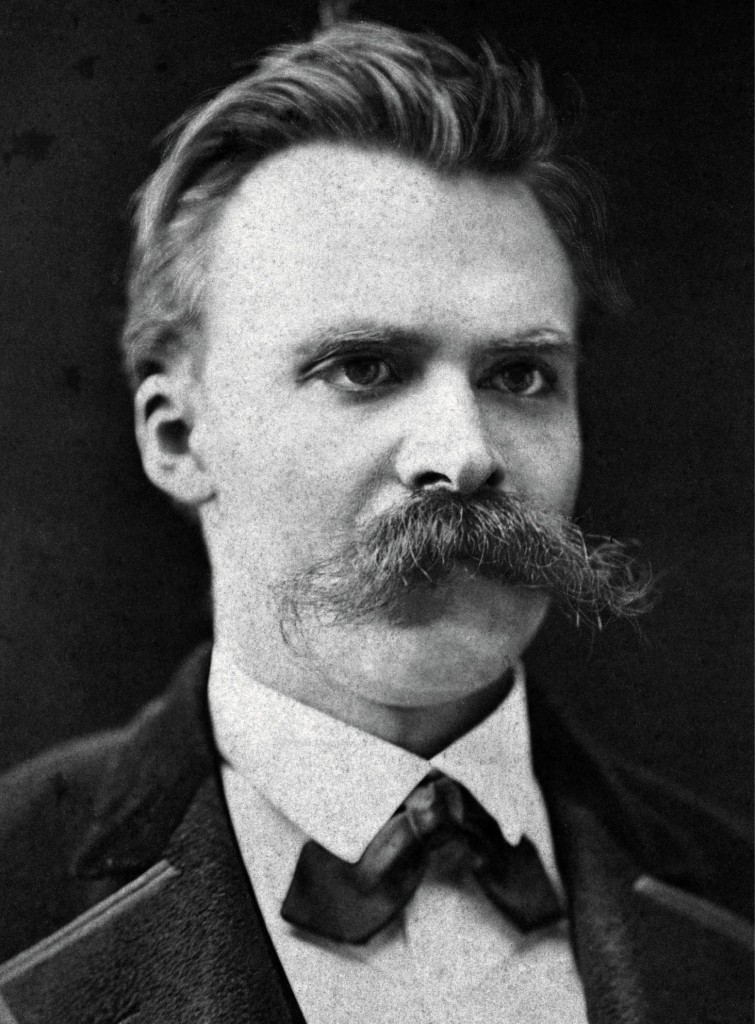

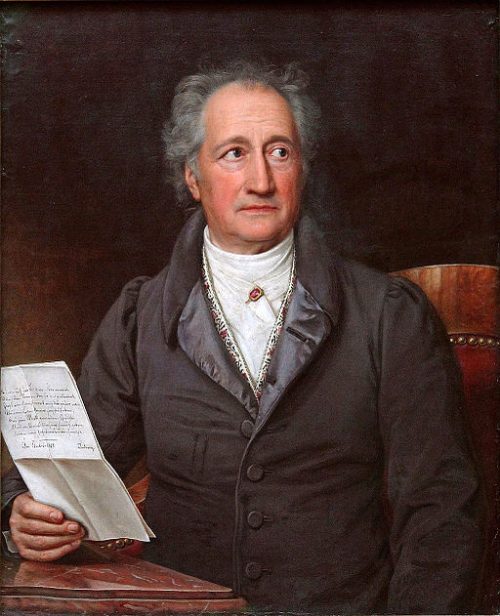

Nietzsche ca. 1875

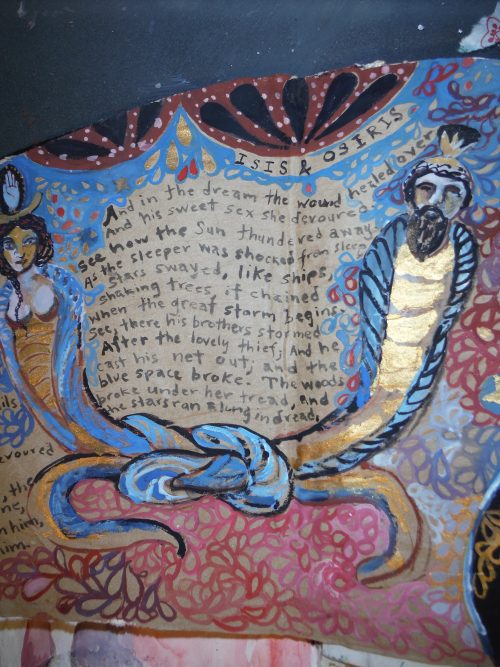

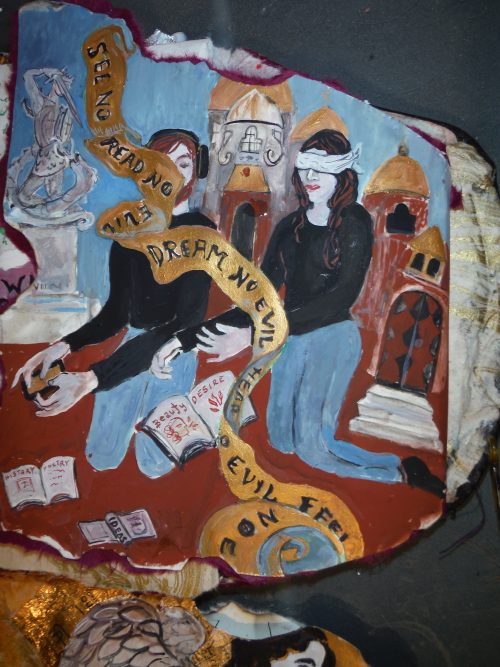

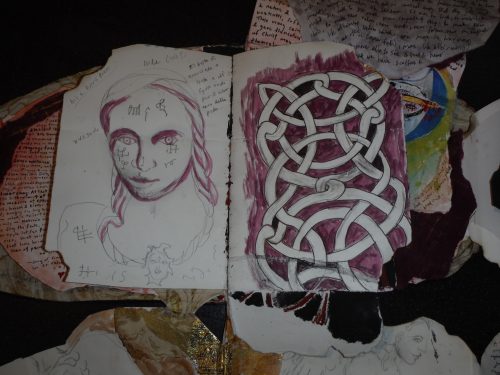

Nietzsche ca. 1875 Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill

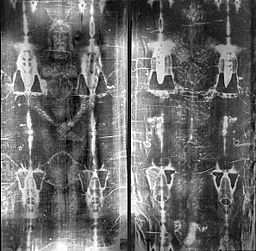

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill Full length negatives of the Shroud of Turin

Full length negatives of the Shroud of Turin

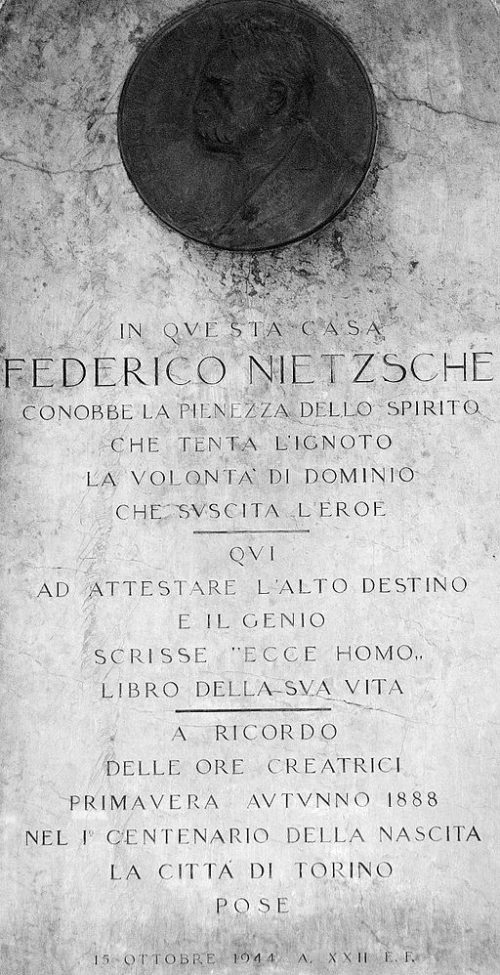

Nietzsche dedicatory plague in Turin

Nietzsche dedicatory plague in Turin

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill.

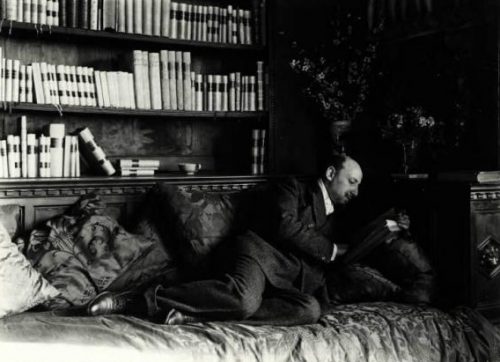

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill. Gabriele D’Annunzio Reading by Mario Nunes Vais (1856-1932)

Gabriele D’Annunzio Reading by Mario Nunes Vais (1856-1932) Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill.

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill.

Richard Farrell

Richard Farrell