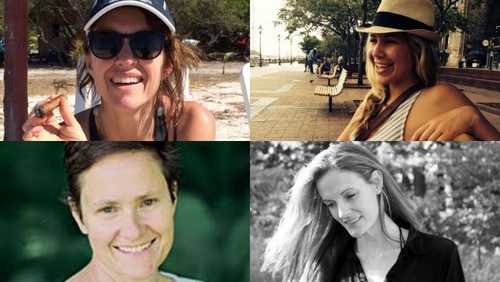

Anita Desai

Anita Desai

.

In his introduction to Moral Agents: Eight American Writers of the 20th century, Edward Mendelson mentions a singularity of the American novel, one that is reflective of its culture: the emphasis on the individual self’s determination and ability to overcome odds. This could mean destiny in certain instances or even convention. There is nothing that can hold the individual back – and the example Mendelson’s offers is that of Mark Twain’s novel, Huckleberry Finn. This theme, however, appears in some of Henry James’ novels: the early ones such as The American, Roderick Hudson and even in Portrait of a Lady, where Isabel Archer tries hard not to settle into the conventional role as society demands of her. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby is about a man who gives himself a new identity and tries hard to chalk out his own destiny.

‘American culture,’ writes Mendelson, ‘has always been troubled by the question of what it means to be an individual person.’ He goes on, ‘In the American novel, on the whole, the goal of the plot is the liberation of the hero… from other people’s values and demands, an escape from all relations of the kind in which individual persons find some accommodation with each other.’ Consider in this light also some works of Ernest Hemingway, where the hero tries hard to find love, but a bigger, larger motive – of fighting battles, of doing a heroic act – always calls him away.

Choice is what drives the individual and it is the individual’s agency that pushes her destiny and even fiction forward. This is unlike, Mendelson suggests, ‘the fictions of Europe where an individual’s life is shaped from outside by large interpersonal forces of culture, history, gender, ethnicity, class, archetype or myth’. In such fiction too, other pulls – of society for example, are far stronger, and the individual is subsumed to it. Interestingly, this difference between American and European cultures appears in Henry James’ works, such as The American, where the brash, assertive American’s ways are contrasted with the more circumspect, more socially conscious French aristocracy.

Such wider forces appear in Asian fiction as well, of which Asian writing in English is a subset. Characters are in thrall to other pressures – long existing, overarching and demanding, and also divinely/religiously sanctioned. In Asia, religion has from time immemorial, formed an integral part of the polity; the strictures of religion and its rules decide an individual’s life. Rulers or the government have the dharma (or ordained duty), then, to uphold what has been thus ‘divinely’ ordained. One’s birth then decided one’s destiny and this or the fates, defined her duties, the role she had to play in different life stages, and choice or agency could do little to circumvent or surpass this. The two famous Hindu ancient Indian epics, Ramayana and Mahabharata, are about individuals who are advised to do their duty; indeed, one’s dharma (way of living rightly) lies just in fulfilling one’s duties sanctioned by tradition and caste.

In ancient societies, where religions like Hinduism and Buddhism have long had a presence, it is received wisdom that individuals are born to certain roles, to certain stations and that it is their destiny or dharma to live according to that. A king serves his subjects, officials function as per the roles they occupy and as defined by caste. On a more unit level, a man has responsibility for his family, a woman serves her family, children are to respect their parents and to grow up within the family and serve it. The individual, in tradition and even in fiction, is defined by the family, whose very reason for existence, and function is decided by culture and religion. There is then little free will; things are pre-destined.

A look at the trajectory of literature in South Asia reveals that the popular works, that travelled primarily by word of mouth before being written down much later, such as the epics or tales from the Panchatantra (tales that sought to impart training to princes), involved individuals performing best as they could their given roles and duties. The novel, it has been suggested, is a western import. Some Indian first novels in the mid-19th century, such as the novels of Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay who wrote India’s first novel in English, and those written soon after in regional languages, reflect the country’s need to question colonial rule, the need to rebel against an unjust foreign power. The individual’s role, in a time of change as seen from the 19th century, appeared in greater measure as the novel emerged. But these still recognized the role of tradition, especially in the domestic realm.

.

The Novels of Anita Desai

The novels of Anita Desai (born 1937) look at present-day and persistent manifestations of the conflict as manifested with the individual arraigned against bigger forces and also the individual’s attempts to subvert destiny. Such subversion, especially in her early novels that feature women, never quite come easy.

In the few interviews she has given, Desai has offered glimpses of her own life: one that did not fall into conventional accepted patterns. It made her in many ways the outsider, and yet gave her an inside view on how the domestic world functioned in India, the relationships and subtle modes of exploitation that existed in traditional families, where the woman was expected to sacrifice her own interests for the greater good – and how bigger events have an impact on small lives.

Her father, Dhiren Mazumdar, a Bengali from Dhaka (then in undivided British India and now the capital of Bangladesh), travelled to Germany as a student of engineering; his father and brother were involved in the Indian freedom struggle against the British that raged then. In pre-war Berlin of the 1930s, Mazumdar met Antoinette Nime, whom he married—something quite different from the usual ‘arranged marriages’ of the time. Desai’s mother, who claimed to have mixed French and German ancestry, never returned to Germany. (Desai’s recollections of Germany, that appear in her Baumgartner’s Bombay (1989), are based largely on her mother’s reminiscences about a home she could never return to, once the Nazis rose to power.)

It was in Mussoorie, a hill town near the Himalayan foothills that Desai was born on June 24th, 1937, one of four siblings. The family later moved to Delhi; again a city where the extended family was absent and thus unable to interfere (an aspect that appears in several of Desai’s novels). Desai lived most of her early life in Old Delhi, the more ancient part of the city; its houses and streets appear in many of her works.

Desai spoke German at home and also knew Hindi, English—her literary language, and the one she read books in first—and then also Bengali and Urdu. She read English at Delhi University and married fairly young at 21, to a businessman with roots in Bombay, Ashvin Desai. Bringing up four children and moving first to Bombay and then Calcutta, Desai wrote her first novel when she was 27. Cry, the Peacock (1963) reveals the confusion and unnamed fears of a young married woman, living in assured privilege, but which precisely becomes the cause for her anguish.

In these early works, the resistance, to familial pressures, on the part of her protagonists is passive and sullen and leads to a helpless, hysterical despair – as indeed in Cry, The Peacock. The object of one’s resistance is somewhat mysterious – for individuals do not (know how to) question tradition or societal sanctions. Her protagonists in subsequent novels have been largely women, though two novels in particular, deal with men whose lives have been disrupted by historical forces. Desai describes the constraints and limitations such tradition imposes, especially on women’s lives. Women have to marry, and have to serve their families. Sons have to study hard to keep the family’s honor and secure a good job to improve the family economically.

Desai, a writer who is part of the first generation of post-independent Indian writers (the 50s and 60s onward) in English, set her stories in this period as well, a time when the country made its first attempts to shake off its colonial past. Jawaharlal Nehru, the country’s first prime minister, talked of a modern nation that would find its place among the world’s bigger powers in a ‘non-aligned’ way – this in a time as the Cold War settled in between the world’s two superpowers, the US and the then Soviet Union.

Indian writers then who wrote in English had, it was understood by the Indian people, a different audience. They were seeking in some sense to explain India to the world, and also present the west’s encounter with tradition, something seen in Desai’s novels. Writing in English – and some writers who were first bilingual moved to English as a deliberate measure – is in contrast with writers in India’s regional languages, who wrote books on important themes such as Partition, of the condition of women, the position of castes considered ‘lower’ in the hierarchy for instance. But their exposure, via translation, has been a more recent occurrence.

It was around the late 1980s that she moved to the west, dividing her time between Delhi and the west. She was first a fellow at Girton College in the UK and then moved on as a faculty to Smith College, Mount Holyoke and then the MIT where she has been teaching since 1993. Her novels of this period, the middle phase of her career, have characters that try and question tradition, or resist convention and societal constraint, not in overtly rebellious ways, but by seeking an undefined spirituality as happens in Journey to Ithaca (1995), through contrarian behavior, that leads to self-destruction as in Fasting, Feasting (1999), and also in the three novellas that constitute The Artist of Disappearance (2012) where resistance appears in forms of ‘renunciation’ or abdication in the manner of the sadhus of old.

Her work, shows this constant questioning on her part, the attempt to understand, with empathy, how ordinary lives might resist, though, as in some of her other novels during this time, the forces now arraigned against them were wider in scope– such as the pulls of history in In Custody (1984) and Baumgartner’s Bombay (1988). Concomitant with her many movements, her stories too move, from India—where most of her novels till the late 1980s are set, to places like Europe, Mexico and the US.

.

Two Conflicting Roles

The figures of householder and ascetic, symbolizing the contrast between individuality and tradition, have been the staples of the ancient Hindu textual tradition. Its epics, mentioned earlier, and law texts such as the Dharmashastras, define duties and laws according to the caste one has been born in. The obligations placed on the individual at every life stage appear to suggest that life is always directed by tradition, responsibilities thrust by society and community.

An individual passes through four stages of life from being a student to setting up house, which is succeeded by retirement and then renunciation: when the individual leaves behind all worldly and household obligations and leaves for the forest. This departure is not just symbolic, for the casting off of ties implies that the character is not bound by her family and household any more. It then becomes a societal obligation to care for the person, for it is understood that they are seeking a higher spirituality, looking for an immersion into God, away from the cycle of birth and death.

The ascetic, then, is one who has renounced it all, someone who has shunned all ties and obligations, for only through such renunciation, as the ancient scriptures have it, can the individual attain salvation (moksha). The ascetic is seeking meaning in a higher spirituality, usually immaterial and unworldly – this isn’t easily defined and is hard to achieve, involving arduous penance, long periods of fasting and usually subjecting the body to all kinds of hardships, in the hope that some divinity would be appeased by such measures and confer blessings.

The householder, on the other hand, is immersed in family obligations and duties, and responsibilities. This contrast in Indian society has engaged sociologists and historians alike, such as the French sociologist, Louis Dumont who suggested, that an ascetic is one “beyond” the caste system; only they could, by professing to break the associations of caste, seek spirituality of a higher order. (It was, on the other hand, easier for those from a higher caste giving it all up; both Mahavira and Buddha, founders of Jainism and Buddhism respectively, were born in Kshatriya (warrior) families). A social historian of colonial India, William R Pinch, writes of the symbiotic relationship between peasants and monks in villages throughout Indian history; each one dependent on the other for well-being and survival. The peasants in their villages, have to provide succor and shelter, as per their dharma, to wandering monks; the latter’s presence graces the village and offers them benediction. He presents to them an idea of their own future.

As the American writer-painter Edwin Lord Weeks noted in the 1890s, the itinerant fakir was a ubiquitous part of Indian life like the crow and the vulture. For all his seriousness, Weeks wrote, the fakir could look grotesque and even an anachronism. Writing of how he came upon fakirs in cities and in villages, Weeks described how the fakir appeared incongruous in the midst of a country that was changing, with new ways of transportation and thought (in the late 19th century, railways covered most of India, except the very remote and there were more modern thoughts of government and rationality among its thinkers). Yet the fakir was left undisturbed where he was, and those who came upon him, even offered him their respects.

This contrast (and also conflict) between these two aspects of life – one in the throes of destiny and another, hoping to subvert or even question destiny – manifests itself in different ways all through Anita Desai’s work from the early 1960s (Cry, The Peacock) to her most recent (The Artist of Disappearance). While the conflict possesses the individual in Desai’s early novels, in sometimes irresolvable ways – either the protagonist is violent to herself, or rebels in little understood ways – in the novels that make up the later phase of her career, there is the quest for renunciation, a search for ‘meaning’ and spirituality, and then, as happens in Desai’s last, very recent work—a collection of three novellas—in 2012 (The Artist of Disappearance), a move towards self-effacement, a vanishing of the self. It appears as if Desai is seeking to provide her own answer or a resolution between these two different ways of living. As the novellas in The Artist of Disappearance show, there are possibilities of fulfillment, and this search can acquire unique meaning for the seeker. It may be hard to understand or to make oneself understood – but this need, very often for her protagonist, for her is immaterial or irrelevant.

Moreover, using quiet, stoic characters, Desai also seeks to reveal what is the inexplicable: the urge to follow one’s desires that drives life, even though these desires may seem mysterious and absurd to others. The nature of happiness and even contentment is indeed strange; her characters seem to suggest. But reaching this stage – that is, the realization that one can live simply without approval, without very many needs – can belie the need to explain oneself to others, in the manner of a true ascetic.

.

A Woman’s Inner Torment

Desai’s first novel, Cry, The Peacock, appeared in 1963 when she was 27. It is rather overwrought, as Desai herself said later, for it lingers greatly on Maya’s inner thoughts and her torment. A young woman finds it hard to overcome her destiny, largely as a dutiful daughter ready to do her father’s bidding. While she is clearly an unhappy wife (in this regard, she is not dutiful to her role), it is the prediction that made about her future, her later destiny, that comes to soon obsess her.

The novel is told from the point of view of Maya and while no dates are given, it is clearly set in the middle of the last century (the 1950s, when India had just become independent). The book begins with the death of Maya’s adored dog, a small Pomeranian. It is a death that appears sudden and unexpected and as the reader soon understands, it is the first death Maya has been witness to. It is this that drives her to hysterics. She sees the death as a premonition of other more unfortunate events: especially other deaths, even her own. Soon after, she sees apparitions and shapes that appear out of the darkness. She remembers then the astrologer’s prediction made about her future when she was still a child.

Maya remembers every detail of this encounter. A man, she remembers vividly, evidently an albino for he is unnaturally pale and who is vividly dressed in fine colored robes and his strange half-dark chamber who she had visited in the company of an ayah when very young. The recent death she has witnessed brings about a resurgence in her memory of this old prophecy: The astrologer had predicted a death for someone very close to her, or even her own. He did not specify a time or even if Maya would be the cause for such a death, but it leaves her horrified. She runs out of the astrologer’s chamber, throwing a tantrum. Later, her father, a progressive lawyer and a widower detached from his children, will dismiss the prediction and life will appear to go on as usual. Maya is married early, as per her father’s wishes, to Gautama, a lawyer colleague, while Arjuna, her beloved older brother, leaves home after quarreling with his father. It strikes the reader that the horror of the prophecy was heightened by Maya’s evident shock at the astrologer’s own appearance.

But losing her dog does unhinge her in several ways. Maya spends hours studying her reflection, preferring the comfort of her own room in contrast to the world outside. She refuses to even sit for long in the garden with her husband. She is unable to understand her own fearful restlessness – for she paces to and fro in her room – and feels only a quick dissatisfaction with all that she sees around her, even the occasions she goes outside. She sees her friends, and how they have ‘adjusted’ to their lives – someone as an unhappily married woman, another married to a perpetually sick man – and she feels a horror at such lives that have no ‘meaning’ left. Such thoughts on life’s meaninglessness and the recent death of an adored pet, bring back the prediction, as a long buried memory, starkly to life.

Maya then cannot seem to stop thinking of it. Bereft of other choices – for as a traditional woman, she is a rich, stay-at-home wife – she comes to be in thrall to this prophecy. Desai describes vividly Maya’s cloistered life, spent in a huge mansion, where she spends time lost in repetitive thoughts or looking at herself in the mirror. Old houses are a motif in Desai’s fiction, appearing as they do in many of her novels, symbolizing decadence and even a claustrophobia of the self. Maya’s repetitive actions, and Maya catches herself at this, make her appear more helpless. The novel spends too much time on Maya’s inner world and her obsession with the house’s silences, its intricate interiors that are also reminiscent of Charlotte Gilman Perkins, The Yellow Wallpaper.

Being a woman, Desai suggests through Maya’s spoilt, pampered, sheltered life, means one is unable to give up the constraints of tradition. It is reflected in the lives of the other women Maya sees around her. Maya does not quite understand how her friends “make do” with life as it comes to them. They are simply caught up in the flow of life; Maya too (despite her name, which in Sanskrit and most Indian languages, means ‘illusion’) finds herself sinking in life’s hard, undiminishing realities. Things, it seems, will be as they have been ordained. She remains dissatisfied with the people she meets, horrified when one of her more ambitious friends gets pregnant; she is stunned into silence by another friend who sacrifices her career in serving her sick husband, and still another, who suffers long at the hands of her husband and yet lies about her social status.

As the novel progresses, it is clear that the astrologer’s prophecy has taken over Maya’s life. She alternates between a withdrawal into herself or basking in false cheer. Always, she remains obsessed with thoughts of death, despite all her striving to find some meaning as to what life could be about. But life’s very mundaneness—especially in how her friends and acquaintances lead their lives —is what turns her off. The traditional family in provincial India in much of Desai’s fiction is oppressive, grasping and stifling, and no member is spared from her piercing description. Every member has a role to fulfill as ordained by destiny, and there is little they can do.

Maya’s husband, Gautama, older than her in years, tries to do his duty by her by being ever solicitous and attentive. He fails, despite or because of his efforts for Maya’s obsession with the death prophecy, makes her fearful of him and also afraid for him. The death she fears could be his, or that he could be the cause of her own death. And Maya, obsessed with death, still hopes to find meaning in life. Gautama (a name that is also the Buddha’s) talks of acceptance as embodied in the Bhagavad Gita. He refers to karma, the results of one’s actions from past lives, and how it reads to reincarnation till one is fortunate to attain ‘moksha’ or salvation. But such answers do not satisfy Maya; they suggest an acceptance of destiny, the very fatalism that drives her to despair.

The novel moves back into the past from the present: In Desai’s novels, ‘analepsis’ is an oft-used technique. There is then a frequent movement to the past – where much of the present is shaped – and then back again. In this novel, almost as a contrast, there is Maya’s brother Arjuna, who ran away from home to escape the rigid authoritarianism of their father. Arjuna, named after the warrior to whom Krishna addressed his message of doing one duty without attachment in the Bhagavad Gita, drops out of Maya’s life for a bit. But in a letter to Maya written several years later, that Maya receives not long after the death of her pet, Arjuna reveals his whereabouts. It appears he now lives in the US, eking out a living in a canning plant. A life lived solely for pleasure, Arjuna writes (almost as if in answer to Maya’s questions to herself), has no meaning. One has to find one’s role in life, and despite subverting tradition, one must be of use to one’s fellow beings. This leaves Maya more confused for she does not know how to question things, unlike her more rebellious brother, though there is a desperation in her trying, in her ability to understand herself and to make herself understood.

The contrasts between the two siblings, one tied to obligations, unable even to break free of an astrologer’s prediction and the other, always questioning, stepping outside boundaries set by his father – appear in how Maya remembers a childhood scene of kite flying. Arjuna’s kite soars high like a hawk while hers resembles a mere ordinary bird, flies almost as if tied to the ground. But for Arjuna too – in a theme not really explored fully by Desai in this novel – there is a constraint for Arjuna realizes he cannot be entirely “free”; he cannot get away from his roots (tradition). As he writes to Maya, in words and thoughts that would appear antiquated to most people today, even the Afro-Americans he works with have to return to Africa, to find their roots.

.

Feminism, Quiet Rebellion and Inanimate Presences

As women have been central to several of her novels, Desai has also been called a feminist writer, a term not really associated with Indian writers in English during this time of the 1960s and 1970s. Feminism—or even protest at traditions in place that historically subjected women—was a concern that emerged among such writers (Indian writers in English) arguably around the 1980s, though criticism of patriarchy and accepted tradition was already established in regional writing – in Urdu, Punjabi, Bengali, Marathi and in the Dravidian languages as well. English was, at the time, considered the language of the elite, more an urban language. In the immediate post-independence years (1940s and 1950s) India’s literacy rates were low (barely 20 percent of the population could read and write; the number now at nearly 80 per cent is much higher). No doubt Desai found herself isolated in some ways. For a long time, she was bracketed by critics and scholars of Indian writing in English into a writerly triumvirate with authors who had partial roots in India such as Ruth Prawer Jhabvala and Meira Chand.

Jhabvala, a German married to an Indian – in a similarity with Anita Desai’s own parentage – was a writer of several short stories and novels such as the Booker winning Heat and Dust, where tradition clearly exerts hold over people’s lives, even when they flout convention in other ways. In a short story, ‘The Judge’s Wife,’ for instance, the family comes to know of their father’s (the judge) second wife only as he is dying, and she turns out to be a meek, quiet and unassuming woman. In Heat and Dust, a British woman comes to India in the footsteps of her step grandmother who had lived during the Raj days.

Jhabvala uses the technique of analepsis – something seen in Desai’s writings too. Heat and Dust is a slow revelation of how the step-grandmother Olivia, chafing under the restrictions of a conservative British society in India, once had a secret affair with the Nawab of a princely state. It led to her taking up a reclusive life, spending the rest of her life in India with her son, born of the Nawab.

Meira Chand, a Singapore based writer of Indo-Swiss parentage, wrote her first novels set in Japan where she lived then. In these works, the woman’s status is always subservient to the demands of her husband and his family. But all three novelists—Desai, Jhabvala and Chand—, with a certain ‘outsider’ status, especially in how they approach their writing, have characters that deal with this matter with a quiet rebellion, evinced in different ways. Chand’s women heroines are usually ‘outsiders’, married into a traditional family and hence they appear more silently questioning. Desai’s characters, in their conflict with tradition and self-assertion, find themselves similarly isolated. They could be loners or eccentrics – largely ignored and forgotten. Desai evokes with empathy their inner lives as they struggle, most often with incomprehension with this conflict.

.

Pressures of Family and History

In Desai’s subsequent novels, following Cry, The Peacock, Desai’s characters, major or minor, strive in various ways, most often not succeeding, to seek release from binding ties and tradition. In Clear Light of Day (1980), Bim, the unmarried older sister of Tara and Raja, protector and preserver of the family’s old house, finds herself resentful of what has been thrust on her. Bim (or Bimala) has, to all apparent purposes, sacrificed her life to look first after her brother Raja, then their autistic younger brother, Baba and their aunt, Mira-masi, who after a lifetime spent looking after them has sunk, in her old age, into a drunken stupor and mad ramblings. The doctor who once had a romantic interest in her surmises that it is Bim’s family whose needs she considers more important and deserving of her sacrifice, but to this Bim has a strange, inexplicable reaction. She laughs, Desai writes. “He had not understood.”

But Bim’s attachment to her family – what remains of it after Mira Masi’s death and even after Raja leaves them – is not really explained. But from Desai’s long and detailed descriptions of their old house, in Delhi located by the river Jamuna, it is the house with its memories, its tradition and especially its past, that has a hold on Bim. As it falls apart, and Bim greys too, it is as if they are synonymous with each other. The house with its garden, and the river slowly silting up is Bim’s domain, though she knows that she too is ephemeral.

The house too appears as a character: Its looming creepers, huge, vacant rooms, columns with their flaky and constantly dropping stone pieces, the abandoned pond where the family cow had once drowned in, and its old forgotten sounds as Baba, the younger brother plays the old records over and over again in his room. Yet, it is the contrast in how the house appears to Bim and Tara, her younger sister, especially in their memories, that shapes the people they have become. Bim becomes attached to the house and its many pulls. She is unable to abandon it, just as she couldn’t their old aunt, Mira-masi, who is becomes helplessly dependent on Bim as senility catches up. All Tara appeared to want, on the other hand, with her early marriage to a diplomat with a promising career, was to leave the house as soon as she could.

In contrast to Tara, Bim remains bitter towards their brother, Raja. While the responsibility of maintaining the house is hers, she resents being officially a tenant – of her brother, Raja, who left to marry into the family of their erstwhile landlord, Hyder Ali. The latter, like all Muslims who had chosen to live on in India (instead of leaving for the new country of Pakistan created with Independence in 1947) felt himself threatened as riots broke out in the run-up independence. He moved south to Hyderabad, a state in India (renamed Andhra Pradesh later) where Muslims found security in numbers.

Raja’s marriage into this family – and Hyder Ali was a mentor of sorts who encouraged Raja’s love of Urdu poetry – and his subsequent abandonment of his old family for he left for Hyderabad leads Bim to cut off ties with him. This doesn’t happen in dramatic fashion, but in the long years of separation, Bim has not written to him even once. The younger sister, Tara, on the other hand, devoted to the family she has married into, wants her natal family – no matter how “dysfunctional” it is (her husband Bakul’s term) – to remain knitted together.

Desai’s novel, in the pattern of analepsis, found in her other works, moves back and forth in time. From the present, where we are confronted with Bim’s animosity towards Raja, we move into the children’s childhood, and understand the special bond Bim had shared with him in the past. This bond is broken when as they grow into maturity, for each of the siblings is pulled by demands of the householder. Bim to the people dependent on her and the house; Raja to the family he now has in Hyderabad, and Tara, who married early to escape the family she knew, is devoted – in a submissive way – to her diplomat husband and their two daughters.

The family, as Desai shows in this novel, exercises a strong hold on the individual, demanding in turn a great cost of individuality. But the two characters in contrast who seem aloof and remote from family obligations, lead shrunken lives. There is Mira-masi, who comes to look after the children when their mother is unwell. But she, widowed early, has been abandoned as well. As a widow, her role in life is to move within the extended family, hoping to be of service to them, in return for a roof and shelter over her head. With no family of her own, she has to serve a family, to survive. There are some figures like Mira-masi, a widow or an unmarried aunt who appear in more than just one Desai novel. An aunt Mira, with a similar religious bent and piety, appears in Desai’s later novel, Fasting, Feasting. It is, as if, with similar names, these women dependent on their families for shelter and help share much the same fate.

In this novel, Baba, the youngest sibling, was born retarded, and is thus rendered forever dependent on his family. It is Bim who ultimately takes care of him. Yet his strange detachment, the way he remains lost in his own world, the constant smile playing about his face, is something that arouses in Bim envy and pity in equal measure. Even random acts of cruelty and negligence that Bim is capable of – such as sending him to office when the traffic on the streets scares him, forcing Tara to pull him back – pass Baba by. He does not appear to understand, and it is the speaker, Bim, who feels the guilt instead. Yet rendered innocent, and guileless in every way, he is helpless too without his family’s support.

The other force, besides destiny and tradition, that exercises an influence in Clear Light of Day, is the historical one. Much of the novel, especially its decisive, critical parts are set in the 1940s: A time of change when much of India is in ferment. In 1947, with independence, Partition of the subcontinent into India and Pakistan, is announced. From the terrace of their house, the three children see firsthand the riots and houses set afire. Hearing of the attacks on Muslims who have still remained in Delhi, Raja fears for their neighbor, Hyder Ali, who speaks Urdu, a language that with the emergence of Hindi in the early 20th century, has come to be associated with Islam.[1]

It is this attachment to the Hyder Ali family that Bim resents. When he leaves to join them, it is almost as if the house they have lived in has been ‘Partitioned’ by Raja’s desertion, as Bim sees it.

In a clear contrast to Cry, The Peacock, which dwells on Maya’s inner life, Desai in her later works, as in Clear Light of Day, is more measured and also oblique. In Clear Light of Day, with its many more cast of characters, there is the same detailing but less dwelling on the inner life and characters are less introspective. Desai shapes them instead, by drawing attention to their quirks, mannerisms, and oddities. Little of their inner lives is revealed for Desai doesn’t get into their mind, but is made evident in how the character is perceived or by her actions. Tara for instance, sees how erratic Bim is in her movements – her frayed dress, her way of talking to herself. Bim says little about her brother Baba, but her devotion to him is clear, as is her cruelty. She sends him to an office – the insurance company in which the family has a stake – and then threatens him with the offer of sending him to Hyderabad to their brother, but later, seeing Baba as usual, unreactive and sleeping peacefully all curled up, she lays down by him, longing to be comforted and to forget – though she has never had the words to say this. Bakul, the snobbish husband, is fastidious in his dressing, and Mira Masi’s descent into madness is detailed by Desai in how she secretly indulges in drinking.

.

Historical Forces

The novel, Baumgartner’s Bombay (1989) also has as its backdrop significant historical events: the rise of the Nazis in Germany and their persecution of Jews like Hugo Baumgartner’s family in Berlin in the 1930s and also the Partition riots that accompanied India’s independence in 1947. Separated by a decade, Hugo Baumgartner witnesses both tragedies firsthand. In some of her novels (such as In Custody), the significant events of her time are told through the lives of ordinary people. As with Bim in Clear Light of Day, in this novel too, there are people, sidelined and forgotten by history, who lead lonely lives but they have seen it all.

Baumgartner’s Bombay begins in Bombay of the 1970s where Hugo Baumgartner, an elderly German Jewish man has tried for the last two decades to make a new life for himself. This life is one of loneliness and increasingly, about nostalgia as well, as Hugo realizing that the past can never return, begins thinking of his own with some wistfulness. This will, as the novel ends, lead him to making some tragic mistakes. Hugo’s own past has been painful. As a child in Germany, Hugo had seen the sad and humiliating descent of his family into poverty. He remembers, in the beginning, a happy childhood, pampered by his mother, and then taken by his father every Sunday on secret outings, as they watched the races and he was allowed a sip of beer from his father’s glass. Looking back, even the imagined ghosts that peopled his father’s furniture store offer hours of dark amusement to Hugo. But this happiness is all too soon threatened and proves evanescent, as the Nazis gain prominence. Hugo well remembers Kristallnacht, the night the Jewish establishments were attacked in Berlin and elsewhere in Germany; the hours he spent cowering in fear inside his quilt.

This vanishing of childhood happiness is vividly described in a few pages: his father’s disappearance one day and equally sudden return as someone who, to Hugo appeared totally transformed, followed by his father’s suicide only a few weeks later, the takeover of the furniture store by his father’s old German partner, and Hugo’s own departure to Bombay – deemed a safe place soon after. His mother, though, refuses to leave. For all the dangers, she cannot bring herself to leave their house, though she is forced to occupy one of the smaller rooms now. This hold that houses have on its occupants evokes Bim and her loyalty to her childhood home in the earlier novel.

Baumgartner then is a man forsaken by the world in every way, who knows happiness can be precarious precisely because it is fleeting and who does not trust identity any more. In different places, in different ways, being who he is has confused him in every way. For instance, his Jewishness had made him a hated and reviled figure during his Berlin childhood; in Venice, as he waited for the steamship to Bombay, his darker skin tone had marked him out as someone different, Asian, and in Bombay, where, he reached as the Second World War raged, he was sent to an internment camp for being from the enemy side: a German in British ruled India.

When the story resumes, after this look back at Hugo’s journey to India, he has in every way renounced his past. His is a life of careful and yet shabby routine, his untidy house is run as efficiently as he can manage. His mornings begin with his running down to a Parsi restaurant to fetch the leftovers for his cats; a habit which has given Baumgartner the nickname, ‘Madman of the Cats.’ For all his hermetic ways, his efforts to live a nondescript way, Hugo retains identity in the wrong ways: a man picked on for his color in Germany (where his darkness gave him away as Jewish), while in India, he is clearly the foreigner, the ‘firangi’- and his foreignness is of multiple dimensions.

But the past – his memories of Germany – remain, especially with his friendship with a dissolute German woman, Lotte, who lives by herself. Once a dancer at a popular Bombay nightclub, Lotte has been abandoned by her patron, a Marwari businessman from Calcutta, and lives on in the flat left to her. It is with her that Hugo enjoys the occasional drink and even flirts, though Lotte sees him as a friend and nothing more. His compassion, his experience of the suffering he has witnessed, make him feel for the victims of India’s Partition riots as well. But Baumgartner is always alone in his compassion. He is indulged in, as Lotte and the Parsi café-owner do, when they engage in small idle conversation with him, but little understood. He is indeed just dismissed as who he is, an elderly German man who sought solace in the company of his cats.

But his past catches up with Hugo when he encounters a German drifter, Kurt, who lies almost comatose in an evidently drug-induced state, in the Parsi’s café. Though the latter in his agitated state, is convinced Kurt is nothing but a ‘hippie’ who lives a dissolute life, Kurt also strikes a chord in Hugo. He offers him shelter and takes him home. In reaching out to Kurt, who he sees only as a fellow German, someone from the country he left behind forever, Baumgartner reveals that he has never really renounced the past. His friendship and offering help to the drifter are what will cost Baumgartner very dearly.

.

Undefined Search

Anita Desai moved to the United States in the mid-1980s. Her novels made the shift too, though her concerns – on issues of divided selves and the conflict between tradition and renunciation or abandonment – stayed the same. Journey to Ithaca written in 1995 takes its title from the well-known poem by Cavafy, that was titled ‘Ithaka.’

Constantine Cavafy (CP Cavafy, 1863-1933), widely hailed as “the most distinguished Greek poet of the 20th century). Of Greek origin, Cavafy was born in Alexandria, Egypt where his parents had moved in the mid-19th century. In his youth, he lived between Liverpool, England, and Constantinople (now Istanbul), in Turkey, before returning to Alexandria, where he worked as a civil servant and where he died of cancer in 1833. His poems, haunting, direct and flat in tone, are also “highly personal” for Cavafy kept his homosexuality a secret and was tormented by it. They also encompass a range of themes and subjects- history, myth, and literature. The theme of Desai’s novel takes on the message that Cavafy conveys in describing the Greek hero Odysseus’ return to Ithaca after the long war with Troy: it is the journey that matters, for it transforms one far more than reaching the actual destination does.

As Cavafy writes in Ithaka:[2]

Keep Ithaka always in your mind.

Arriving there is what you are destined for.

But do not hurry the journey at all.

Better if it lasts for years,

so you are old by the time you reach the island,

wealthy with all you have gained on the way,

not expecting Ithaka to make you rich.

The urge to leave family bonds, the past behind and to become a seeker and ascetic, is what drives Matteo, and in a different way, his wife Sophie in Desai’s Journey to Ithaca. The story begins from Italy of the 1920s and moves to Europe between the wars to 1970 when the hippies or the flower children are drawn to India. Journey to Ithaca is a story about seeking, the need to find spiritual realization, the need to go on a pilgrimage. This is an all-consuming urge, driving the seeker toward a spiritual union with a greater spirit or truth. But Desai also points out that renunciation, though it may appear in contrast to all sorts of binds and ties, is in turn a total devotion to an ideal, and hence forms a kind of bondage.

Matteo is drawn to the spirituality of the East, when as a young boy, frail in health and subject to frequent bullying in school, is tutored at home. It is his tutor who introduces him to Herman Hesse’s Journey to the East, a book that comes to entrance Matteo totally. It is about a group of travelers, some real historical characters and others mythical, who travel to the East in search of Truth. On the way, however, as they pass the night near a particularly treacherous gorge in Europe, they are abandoned by their attendant, Leo. It throws the journey into confusion but as is revealed later, by the narrator, the journey, Leo’s abandonment of them, was a test in itself, of their own deep faith in the journey.

Matteo’s early confusion is never directly revealed in the novel except in how he behaves – his hatred of boarding school, the usual games boys his age play, his misery in working in his uncle’s silk factory in Milan, and then his decision to leave his family. The latter isn’t stated but is apparent from the broad sweeps the novel makes across time. Matteo leaves soon after his marriage to Sophie, a German, whose father moved in the same financial circles as did Matteo’s father. Evidently Matteo expected Sophie to fall in with his plans and they leave together for India. Sophie, devoted to Matteo, is also the beginning, first dazzled by the flower children, and their freedom. However, the bitter truth about them soon dawns on Sophie as Desai dispassionately describes their cunning ways, and ways of sponging off each other. Sophie also sees through the many godmen Matteo visits, and their assistants, who it seems, will eagerly leech off any gullible white foreigner looking for the ultimate spiritual experience. As Matteo tries out one spiritual experiment after another – going on long, arduous pilgrimages, meditating and giving himself up to a chosen godman’s prescriptions for living – Sophie for her part, longs to be home. Yet she cannot bring herself to abandon Matteo, even as she is left increasingly puzzled and then angry by this elusive search.

When they are part of a long pilgrimage procession, Sophie encounters a fellow pilgrim, a mother with her ailing, barely surviving, child. The mother’s need to seek spiritual, rather than the medical help, her child so urgently requires puzzles Sophie. She also doesn’t understand Matteo when he finally appears to find some solace with a mysterious “god woman” (a spiritual figure), with a carefully concealed past (as Sophie soon realizes), and who lives in a hill town. The god woman is called ‘Mother’, a name she evidently assumed and she is addressed this way by all her acolytes and disciples who see her as a parental figure of some authority. All of them live in the ashram and among themselves, share the responsibility of running it, though it is Mother who calls the shots.

It is Matteo’s utter devotion to her, something different from occasions in the past that Sophie has been witness to, which alarms her. She is suspicious of Mother and also sneering of Matteo’s apparent high regard of her. This prompts her to go on a search to lay bare the true identity of the ‘Mother’, leaving her two young children in the care of her parents in Germany. The Mother appears a spiritual ‘godmother’, but Sophie is convinced that she is a charlatan who has bedazzled Matteo. Her search to dig into the Mother’s past, which takes on almost the contours of a detective novel, instead reveals to Sophie some truths, if not the kind of truth – the Mother’s true nature – she has been seeking.

The Mother’s past has been a carefully kept secret, but Sophie retraces her steps painstakingly and carefully, first to Alexandria in Egypt where the Mother, as a young girl called Laila had spent her youth. Later, Sophie follows Laila’s footsteps to Paris, where the latter’s restlessness, her impatience at her aunt’s snobbishness finally leads her to the ‘guru’, a dance teacher visiting with his troupe from India. The Master’s depiction of Krishna, the Hindu god, enthralls her: in this dance form that combines passion with mysticism, Laila feels she has finally found her reason for living. Soon she leaves to be part of his troupe. But barely a few months later in Venice, she is disillusioned, as she sees that the master too is driven by practical things. He bargains with his patrons over the littlest of things, is demanding of favors and privileges, and is not averse to making the other female dancers jealous simply to get his own way.

Laila, however, is determined to go to India. If not with the Master, she is certain of finding some spiritual meaning there. Her yearning, one that is undefined and yet that takes over her every sense, has made her physically sick – a sickness in some senses that afflicts Matteo too. On a visit to the north of India, she finds some solace in a guru – though Desai says nothing about him, or even describes him. It is almost as if, in Desai’s vision, the individual’s quest for salvation, and even its seeming culmination, remain inexplicable and also mysterious. It is in this ashram of which Mother is now in charge that Matteo too finds her and comes to live. Sophie thus in a way comes to understand Matteo’s need to look for a truth, however elusive. It is something akin to what Sophie had also understood about Laila. In Paris, as a young student, Laila realizes that what draws her is some kind of passion – one not just of celebration but also the passion of renunciation.

.

Old Concerns and New Themes

The conflict in Desai’s novels between the ascetic and householder returns in Fasting, Feasting (1999), with the figure of the householder embodied in Uma who is resentful of her sheltered life and yearns for a different existence. In this novel, set in a traditional family living in Delhi (in a house and time that evokes Desai’s Clear Light of Day) there is rebellion of a kind. Uma, for years spent serving her parents’ needs, longs to give it up, and when thwarted, and unable to express herself, shows some sullen resistance.

Uma has been a failure in school. Forced to drop out after being unable to clear her final examination for a class, she becomes almost a young second mother to her youngest sibling, the brother and only son of the family, Arun. Sometime later, Uma’s parents arrange a dowry for her but her marriage ends in shame, as the family, it appears, has been cheated. The groom, it soon turns out, is already married but had availed himself of the dowry offered by Uma’s family to improve his own business. Desai sees this as a pattern and it recurs in the novel: the groom’s family, all too aware of the desperation among some families to see daughters married off quickly as per tradition, milks them for all the dowry they can demand.

Uma also disappoints her family in her inability to make a good marriage. Desai depicts how marriage can transform a woman’s life and how it is an entrapment of a kind: Uma’s sister Aruna, becomes a flighty, superficial creature, concerned with family matters that to Uma appear shallow. There is also the tragedy that befell their brilliant cousin Anamika, who had once secured a scholarship to Oxford but who, only some years into her marriage, is killed by her in-laws, for not pleasing them in various ways. Anamika’s death, from burns is passed off as suicide, but as had always been acknowledged by her family, the dowry Anamika had brought with her on marriage had never been enough. There had always been constant demands, which Anamika’s parents found hard to meet and her in-laws became harder to please than ever.

With her failed marriage and other failures, Uma’s life becomes one of constant service to her family, its needs and that of the old rambling house they live in. But she is drawn to her prodigal cousin, Ramu, whom the family disapproves of, for all his degenerate ways. She is also attached to her wandering aunt, Mira-masi, who lives the pilgrim’s life, moving from one temple town to another, or between ashrams, looking for salvation. Her long arduous penance, her frequent periods of going on fast, all in search for an elusive salvation – the only goal permitted to an abandoned young widow left to the mercy of relatives – is what gives this part of the novel its name: Fasting.

There are also the nuns in Uma’s school, who find happiness in service. Uma has ways of rebelling quietly, of showing resentment subtly: sometimes she has fits, she goes out for dinner with her cousin Ramu—someone her parents disapprove of—and returns late on such occasions. In a last show of defiance, she calls up on the sly, the nuns in her school who have offered her a job (running a ward in a missionary run hospital), for her parents do not approve of women seeking a career for themselves. Though this is a later work, written in 1999, Desai is clearly evincing more modern concerns relating to India – as women seek more education and want a career for themselves. However, in traditional societies, as with Uma’s family, conservative thought patterns and modes of life remain hard to break. Her parents are adamant about Uma not pursuing her own career. Uma, resentful and sullen, is unable to break free.

Almost in contrast to Uma, the section on Feasting dwells on her brother, Arun, the family’s only son, on whom their hopes rest. Though nothing has ever been denied him, Arun is glad in many ways to be away in the United States, as he finds hard to bear the constant attention and oppressive demands made on him as the only son in the family. His every waking hour had been carefully monitored by his father, who sent him to the best schools, employed tutors, and looked to his every need. It was a parental love tinged with ambition: Arun’s later success, it was believed, would bring prestige and honor to the family. Their status within the community would rise.

In the US, where he is at university, and away from family ties, Arun shies away from emotional attachment of any kind. In fact, despite his isolation, he is relieved to be free from family pressures and expectations. As Arun looks for accommodation during the summer, he rejects any that will demand any kind of human contact for him. But then finally, when an accommodation is picked for him, thanks to people known to his sister Uma, he finds himself immersed in the daily conflicts of an American family.

Oppression of another kind appears in how his landlady, Mrs. Patton’s daughter, Melanie, rejects in her teenage rebellion, all the food her mother—in the hope that such food, home-cooked will be nutritious and sustaining—has cooked for her. This is Mrs. Patton’s way of making Arun feel welcome for the food, in accordance with Arun’s traditional habits, is vegetarian. Melanie, however, chooses to gorge herself on junk food, throwing it all up later. She is evidently a secret bulimic and her parents, realizing the reasons for Melanie’s strange rebellion later, send her for rehab. Arun is amazed at the sheer wastage of food: not just on Melanie’s part but the amount his host buys at the mall, much of which goes unused and rots.

This latter section on Feasting reflects Anita Desai’s own observations about life in the US: the loneliness and demands of college life, the communication gap (of a kind different than in India where tradition and conservatism breeds silence between generations) within families, and the over-consumption; the earlier section that dwells on Uma and her life in Delhi, appears an extension of her earlier concerns in Clear Light of Day. However, in this novel Uma’s anger is more evident. The widowed aunt, Mira-masi, is clearly not dependent on any family but is on her own, visiting temples and places of pilgrimage and even ashrams, where Uma accompanies her on one occasion. Desai builds up Mira-masi almost as a humorous figure; through her, Desai exposes some essential societal flaws. Her pilgrimage isn’t really a search, but one that is thrust on Mira-masi, because she is a widow and has nowhere else to go, nothing else to do. A wandering ascetic life, with all its accompanying austerities is thus thrust on unfortunate women like Mira-masi.

.

Self-Effacement

This search for what makes the complete or ‘true’ renouncer is most apparent in Desai’s most recent published work, a collection of novellas, The Artist of Disappearance (2012). In the three long stories that make up this collection, there is an inner passion and search for ‘self-realization’ but this is subdued. Self-effacement appears in entirely different ways. The passion is deeply internal, spent on pursuits that appear ‘strange’, yet these characters in her novellas appear happy.

The aristocrat in ‘The Museum of Final Journeys’ collects a variety of things from all over the world, to be housed in some rooms of his mansion, of which he is the sole occupant. Once he even procures an elephant who lives in its own shed outside. It appears just a useless hobby, for the collection is ersatz, random and has no order to it. Moreover, he has no heir to pass all this on. It will all go to the state, and the administrator, who is the narrator, is nonplussed at the sight that befalls him. While the latter wonders as to what to make of it all, and how to acquire and disperse in some order, this collection (including the elephant), he also understands in some vague, inchoate way, the aristocrat collector’s reasons: He did it simply to make himself happy. The act of collecting is all that evidently mattered to the aristocrat.

‘Translator Translated’ is about a lonely teacher, Prema, who at the behest of an old college friend, tries her hand at translating. Prema decides to introduce an unknown writer in Odia (one of India’s fourteen recognized languages), Suvarna Devi, by translating her works into English. This will, Prema believes, bring Suvarna Devi, the fame she so rightly deserves. Prema gets passionately involved in her work and in the author too. The translator begins taking a possessive interest in the author’s life, almost as if she is responsible for giving her a new one, and a new identity too. When one of Suvarna Devi’s later works comes to Prema, the latter finds it full of errors and insipid in some ways. It is then that she begins, inadvertently at first and then very deliberately, changing the meaning of the original text, even a word here and there, and then she gets bolder. Later, one of the author’s relatives accuses her of rendering the work wrongly. But the author herself remains a nondescript, shy person who is content to let things be. Prema’s attempts at making a new life for herself, fashioning herself in a new light, come to nothing, as all she does is try to live through another.

‘The Artist of Disappearance’, the title story, is a man who lives an isolated life and thrives in it. Born unloved and largely uncared for, Ravi has become a recluse. His life becomes to all intents and purposes, pathetically circumscribed though he does not think so. He lives in part of a house that has long burned down and his needs are looked after by a cow herd family that lives near. Ravi instead is happy spending hours looking at the minutiae of life unfolding around him: a snail uncurling itself, a spider at work and once in Bombay, he experienced bliss staring down at the shallow depths of the sea and seeing the tiny life beneath. With the death of his mother’s old nurse, Ravi removes himself from every contact with society. He comes to nurse a secret glade, located amidst certain boulders in the hill town he now lives in, making it beautiful by planting trees, and arranging nature in careful patterned ways. This remains undiscovered and unknown till a television crew member stumbles on it. She convinces her team to film the glade and even interview its creator. But as the search for him grows, Ravi chooses to evade them.

Dressed in the clothes given him by the cow herd family, he appears just a nondescript idle local, whiling the afternoon away. However, when the crew examines its reel footage of the glade, it appears to them perfectly ordinary, even whimsical; the footage is discarded. What Desai seeks to say is that an act of creation could exist simply to make its creator happy. Creation can bring about fulfillment, even to those merely observing, as does the film crew member. By extension, Desai is perhaps suggesting the self-effacing nature of the true creator.

.

Threads that Tie Desai’s Work

Inner Conflict – something that is inevitable in every individual life – can only be assuaged by an inner peace, Desai seems to suggest in her work. For instance, all the three characters in her last work have chosen to shun the limelight, from the need to constantly engage with the outside world and have thus found peace of a kind – though this is never clearly defined. But it does take artistry, as denoted by the last story, to efface oneself totally.

The conflict is, moreover, focused on her character’s inner life. In her novels, she also visually describes this conflict as one symbolized by crowded chaotic outer worlds that is totally opposed to solitude, an individual’s desire for peace. Old houses, packed with bric-a-brac appear in Clear Light of Day, Baumgartner’s Bombay and Fasting, Feasting, symbolizing the past and memories, evoking the weight of tradition, responsibility and pressures. In Journey to Ithaca, Matteo longs to escape the imposing mansion of his rich parents. In contrast, the ashram rooms he lives in, are shabby and without any amenities, yet he is not bothered. The crowded mansion room, with its vast collection of objects that make no coherent sense, is best expressed in the first story of her last novella, The Artist of Disappearance.

Her way of offering a resolution is the suggestion that this search for inner contentment, must be all self-driven. Even renunciation as embodied in the figure of the ascetic is of little use, rather Desai, whether in her short stories or in her novels, renders the figure of the ascetic or godman (god woman) in humorous ways or even as someone suspicious. In one of her stories in the collection Diamond Dust (2000), a philosopher friend comes visiting Sarla just when she is preparing to leave for the hills. And their lives are thrown upside down as they have to arrange parties and meetings on his behalf. Laila, or the Mother, is scheming, the ashram is a cloistered space, and Matteo is hapless. Laila is someone who can never win Sophie’s trust while she has Matteo’s dogged devotion. Ashrams, that appear places of solitude and peace, assume a sinister character, with their rigid discipline. Uma in Fasting, Feasting is taken by her aunt to one has the first of her fainting spells there. Journey to Ithaca describes the different kinds of ashrams in which Matteo and Sophie find themselves. Their shabbiness, suspicion, for all the communal atmosphere, make the ashram a place of immense danger.

In The Artist of Disappearance, the ‘search’ for fulfillment or peace has been given up though it is not that Desai has been actively looking for such a resolution The three characters in the narratives do not travel anywhere, and even their motivations are not explained. It is a mysterious and all fulfilling kind of self-effacement, when even the self – or ego – does not strive to belong and is not bothered to ask questions or even answer them.

Human nature, Desai then suggests in her works, is born to conflict, for an individual is subjected to pulls and pressures of every kind. Her focus in her early novels was on traditional families, with women, unable to question the force of tradition and long accepted rules of living. Those who ‘renounced’ were those who had been “given up” by the family – the widowed or unmarried aunt – and never the other way around, as in the true tradition of holy sages and ascetics. It is through her characters, like Matteo, in Journey to Ithaca, that Desai tries to explore in turn the contrary pull of renunciation (as opposed to living the householder’s life). She suggests that renunciation too is a bond of a kind.

Is self-effacement, finding happiness – or rather fulfillment, which is how Desai sees it – in undefined ways, the key to resolving such conflict? Prema’s search for fulfillment by finding a new identity in another, leaves her unfulfilled; while Ravi’s creation appears too fragile and evanescent. But for Suvarna Devi, the author Prema translated, simply the act of writing was enough, just as making a small secret garden have Ravi some secret pleasure. The Artist of Disappearance leaves us with more questions and rightly so, for a writer’s work is to ask the necessary questions. Human existence, it appears by a reading of some of Desai’s works, is a search for answers to this conflict and the search remains an enduring one.

—Anu Kumar

.

Bibliography

Desai Anita. Cry, the Peacock, Orient Paperbacks, 1967

__________. Clear Light of Day, Penguin Random House, New Delhi, 1980

__________. Baumgartner’s Bombay, Penguin Random House, 1989

__________. Journey to Ithaca, Penguin Random House, 1995

__________. Fasting Feasting, Penguin Random House, 1999

__________. The Artist of Disappearance, Penguin Random House, 2012

Dumont, Louis. Homo Heirarchichus: The Caste System and Its Implications. University of Chicago Press. 1979.

Keeley, Edmund and Philip Sherrad (translated). C.P. Cavafy, Collected Poems. Edited by George Savidis. Revised Edition. Princeton University Press, 1992; http://www.cavafy.com/poems/content.asp?cat=1&id=74

Jhabvala, Ruth Prawer. Heat and Dust. Counterpoint. 1999

Mendelsohn, Edward. ‘Introduction.’ In Moral Agents: Eight Twentieth Century American Writers. New York Review of Books. 2015.

Pinch, William R. Peasant and Monks in British India. University of California Press. 1996.

.

Anu Kumar is in the MFA Program of Writing at VCFA (2014-16). She resides in Baltimore, Maryland, and has lived in India and Singapore before.

.

The glass images between the poems are examples of work by the poet Michael Ray. More can be seen here and here.

The glass images between the poems are examples of work by the poet Michael Ray. More can be seen here and here.

Anita Desai

Anita Desai