In the mid-nineties, I returned to Ireland from Washington State having completed my MFA in Creative Writing at Eastern Washington University. I was young, heady on a mix of Russell Banks, Ray Carver, Tobias Wolff, Richard Ford et al. Ford, it seemed had taken it up a notch. His characters less inclined towards defeat (than many of the other so called “minimalist” writers) and more inclined to take some control upon their lives, to seek some form of transcendence or at the very least self-knowledge. But the landscapes were harsh, crude, rugged, the lives equally so- in any case, I was a visitor and intoxicated with the abundance of, for me, unexplored literary territory. I returned to Ireland with an expectation of disappointment – back home to a familiar landscape, a familiar literature.

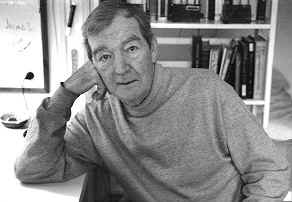

Into this entered John MacKenna’s collection of stories, A Year of Our Lives, published shortly after I returned – at first glance, as far removed from Ford and my intoxication as I could imagine and yet… strangely similar – minimalist yes, the landscapes harsh, the narrative confessional but revelatory –It provided me with a way back in, a fresh vantage point. A few years later I was off on my journeys again, but the beauty and lyricism of MacKenna’s writing has remained with me since….soberly beckons me home.

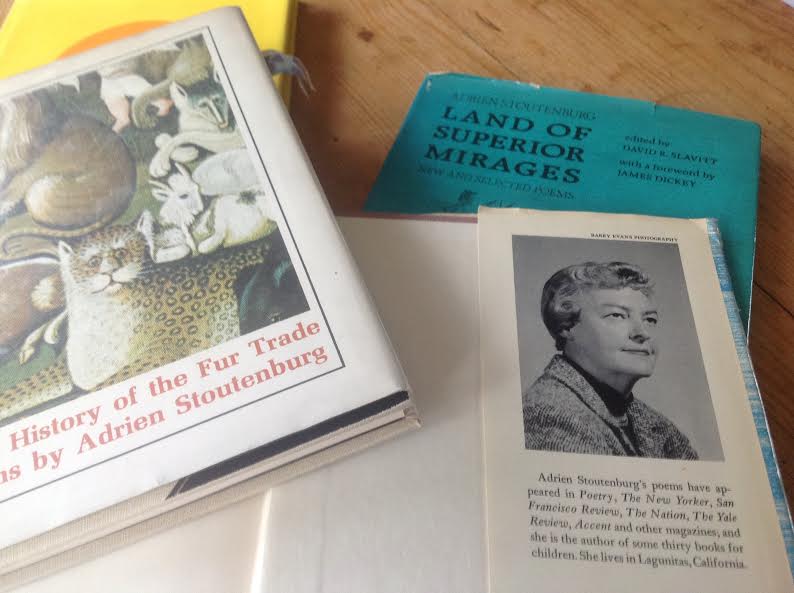

“The Angel Said” is from a new collection, Once We Sang Like Other Men – “a book of thirteen stories based on twelve men who followed a socio-political leader to his execution and now, twenty-five years later – are scattered across the globe.” His novel Joseph (coming from New Island Press in September) is a contemporary telling of Joseph the carpenter’s story and the collection is a contemporary retelling of the stories of the twelve apostles – Peter telling the first and last stories, thus the thirteen.

— Gerard Beirne

§

I sit at the small table and eat my breakfast, wondering, as I wonder every morning, where my brother is. I ask myself the questions I ask first thing each morning and last thing each night. Is Peter alive? Will we ever find each other again? Does he wish to meet or has too much icy water flowed under the bridges of experience? Then I wonder if he’s well and if he’s enjoying his life greatly or to some extent or at all. Is he happy or at least content? And then I stop this gradation of life, this slotting of emotions into pockets.

I wish him only happiness.

I don’t wonder if he thinks of me. That thought has no part in this daily process. That’s for a time I rarely dare to dream about, a time when we might meet and sit and drink coffee and talk or not talk, a time when we might recapture in silence the warm energy and the familiarity of our comradeship.

And then I finish my breakfast and watch the passing shapes of the figures in the street – quavers and semi-quavers with minims in tow; figures of darkness and, occasionally, figures blessed by the light of the falling snow.

Once my morning meal is over, I go and wash in the small bathroom that is never bright and never warm. Snow piles halfway up the thick little windowpane in winter and pigeons squat there, blocking and unblocking the light with their comings and goings all year round. In winter I stop shaving; it’s easier that way. My beard sprouts in all directions and for those few months I can imagine that I might have been born here, might be one of these people and not an interloper from somewhere beyond the Black Sea.

In the small room that houses my bed and my instruments and music, I perform my little ritual of tidying, as I do every morning, carefully straightening the sheets, punching my pillows into shape. I take my violin from its case, randomly choose a piece of sheet music – probably the only random thing I will do in any day – and place it on the music stand. I pause and then play the chosen piece through twice, before carefully replacing my violin in its case and putting the sheet music back in its ordered spot.

Beyond the window, in the cemetery, young boys are throwing snowballs, dodging behind the headstones, squatting in the shelter of small crosses before launching their next attack on each other. Their voices come faintly across the ledgered lines of memorials, some as dour as those they commemorate; some sporting bowed ribbons for the season of the living; a few splashed with the petals of winter flowers. Two young girls in very short skirts and skimpy tops stand at the gate of the cemetery watching until the boys, in a show of bluster, turn their icy fire on them and drive them laughing through the gates of death and back onto the living street.

I leave the room, closing the door behind me, and complete the other odds and ends that need doing – making sandwiches, washing my cup and plate before putting on a coat, scarf and hat and leaving my apartment for the short walk to the church where I work as choirmaster.

I am a creature of habit. Perhaps I was always so, though I like to think there were weeks and even months when I was otherwise, the weeks and months when Peter was about.

There is a young boy sitting on the narrow stairs of his parents’ house. It is late in the night; more than late, it is the early hours of the morning. The boy sits in the most uncomfortable position possible, his back arched and aching, his hands clasped tightly about his knees, his fingers welded painfully together. He does not move. His pyjamas are thin and the night is cold, but he wants to suffer. He hopes that he can barter with God, swap his discomfort for his parents’ happiness. If he sits here for another sixteen minutes and forty seconds, if he counts to a thousand – slowly – then the arguing will end, peace will flutter through the winter window like the angel of the Lord and happiness will, at last, be tangible. Despite his youth, he understands the meaning of the word tangible.

What he doesn’t understand, though he has an intimation of it, is why he is being used as a shield in a marriage that seems incapable of generating anything but anger and discontent. Even he, a boy of ten, can see how much better life would be for everyone if the owners of the voices from the kitchen were to move elsewhere, one to one end of the village, one to the other. But, instead, the war goes on, and his welfare is invoked as a justification by both parents.

If it wasn’t for….

Well I’m not going to walk out and leave ….

An intermediary without power, the phrase pops like an organ stop as I’m locking the door at the foot of the stairs.

That is what I was. An ineffective go-between, my role defined by those who needed to justify themselves.

“Without power or respect,” I add out loud.

A passing figure looks up, frowns an even deeper frown and then returns his eyes to the frozen snow that pleats the footpath. I turn my key a third time and the lock creaks into place. I try the door: locked, tight.

I look up, as I do every morning at the massive edifice that is my workplace. It sits like a great bird, its profile moving slowly across the summer days, its darkness a permanence on the winter skyline. Nothing in this part of the city can exist without this reference pile impinging on its being. No one who lives in this quarter can get into or out of bed without its real or imagined shadow gouging a deep, slow path across their dreams and imaginings.

The young boy, who sat on the winter stairs, stands at the edge of the sea. The late summer sun is bending and creasing the horizon in shades of red and orange and ochre. The setting sunlight is still warm on his face and he knows that it will hardly be gone from one sky before it pushes like a cerise mushroom into the other sky, sidling above the morning mountains.

As yet, the rising dread as the time for his brother’s return to sea approaches has not become the uppermost thought in the young boy’s head. He is happy in the knowledge that the dark shape in the crimson water is his brother’s punt, moving between the lobster pots, and that before the sun has gone down Peter will be stepping from that small boat into the water and he will rush to help. They will paddle through the shallows, each with a hand on the light gunwale, lifting the boat clear of the sea, leaving a track on the pale sand as they drag it above the tidemark.

“Good man,” his brother will say. “Only for you.”

“You’d have got it clear on your own.”

“But together we’re better.”

The phrase will stick in his mind. The phrase will become his mantra and will keep him afloat in the days after Peter has gone back to his naval training.

“I like when you’re here,” the young boy says, uncertainly.

His brother turns the punt over and it lies like a turtle on the sand.

“I know. It’s tough for you. Being here with them when they’re like this. But it probably seems a lot worse for you. I don’t think they even notice that they’re arguing. It’s a way of life for them. They’d miss it if they couldn’t bicker.”

His brother smiles but the young boy feels a frozen rock lodged in his stomach.

“Hey, I’m not gone yet,” Peter laughs. “Let’s do something tomorrow. Let’s take the sailboat out and have a picnic and when we get back we’ll go to the cinema. A day away, just the two of us, all day. We’ll get up early, be gone before they’re even awake. Ok?”

The young boy smiles a big smile and his brother puts his arm around him and they do the elephant walk all the way up the beach.

I make my way, as I do each morning, through the cemetery, wandering between the stones, walking every path. I have my own reason for taking this circuitous route. It’s not to familiarise myself with the faces and names and dates on the monuments; nor is it the strange attraction of the military section of the burial ground – though I always stop there and consider the remarkable cholera of loss with which the twentieth century infected this country: the Great War; the Revolution; the Second World War, an infection that recurred with devastating consequences.

But it’s not this remembered wretchedness that is the object of my morning walk. My stopping is simply a way to justify the other stop I make on a daily basis, putting it in the safe keeping of the routine. If I linger among the war dead, then why should I not stop, too, at the grave of Nikolai Kalinnikov? If one is habit, why should the other not be just the same?

Sometimes my caution angers me. Why should a choirmaster not stop to remember his choirboy? Why should one human being require an excuse to linger at the grave of another? What is it that I fear?

Nikolai Kalinnikov will have been resting here for two years in one month’s time. His anniversary is bearing down upon us and we will remember him in word and music when the day comes round and I, perhaps, will remember him more than most. His burning eyes and sweet laughter, his energy and constant sense of fun, that occasional and guarded smile that was the antithesis of laughter. A smile that was as infrequent as it was promising.

Other than in the course of my duties, I doubt I spoke personally to Nikolai more than a dozen times in the almost three years we spent together as teacher and pupil. But when I did, I saw a different person, not the wild young thing who was always rushing; not the urchin who laughed at every joke; not the boy who was forever involved in pranks, and not the chorister whose voice was deeply beautiful. I saw a child becoming a young man; eyes that were intense and a smile that asked and promised everything.

I loved Nikolai Kalinnikov. Not with some seedy, leering intent. Not with thoughts of touching or being touched by him. Not with the intention of his sleeping in my bed, but with a love that made me happy and sought only for his happiness. I never laid a finger on his skin, never kissed his face, never considered such possibilities and yet something in that enigmatic smile made me believe that he might some day kiss my mouth, touch my skin, that he might suggest we lie together in a distant future – not here but, perhaps, on the warmer shores of my own country.

And then, one bitter morning two winters ago, he leapt, as he always did, from the open door of the city tram as it slowed on the corner beside the church. Not for Nikolai the one-minute walk from the next stop. Life was too full to waste time in walking backwards from a point that had no necessary place in that day’s itinerary.

So he leapt, as he always leapt, running to keep pace with the tram before making the safety of the footpath. I had seen him do it many times but I wasn’t there that morning to watch his legs go from under him and his knees buckle as the tram unexpectedly picked up speed. He slipped – not for the first time – and skidded on the packed ice beside the tram tracks, but on this occasion, rather than tumbling harmlessly, to the amusement of his fellows, he slid across the ice, body spinning until the force of his skull against the pavement kerb brought his fall and his life to an end.

I saw his body that afternoon. Two of us teachers were dispatched to formally identify his remains, to spare his parents the trauma. Ironically, we travelled on the very tram from which he had slipped. Someone had placed a small bouquet of winter evergreens on the rear platform from which he had so impulsively and carelessly leapt.

In the hospital we were led to the dismal morgue where Nikolai lay beneath an icy sheet. His handsome young face had barely been scratched by the packed ice, but it had been grazed by death, and I wondered whether that kind of death is any less demeaning than if his features had been ripped and burned by the sharpness of the ice. His vigorous body looked out of place in that charnel house and I thought of another emaciated body, that of a young man who had survived at another time and in a different place, and I was perplexed.

Often on summer evenings, when the young boy’s older brother was away fishing on one or other of the half-dozen trawlers based in the small harbour close to their home, he would walk down to the dock wall and stare at the distant horizon, willing the trawler bow to slice through the evening mist. And sometimes a trawler would appear and the young boy would patrol the low wall, wishing the hull to be red or blue or yellow, depending on which boat his brother had shipped on.

And once, once only, when the boy was at the harbour, the hull was red, as he had hoped, and his brother brought him on board and allowed him to assist with the unloading.

“You have a good helper there, Peter,” one of the trawler men had said.

“None better,” his brother had replied, tousling his hair and smiling at him, and the young boy had felt a pedestal rise beneath his feet and wished he could travel for ever in the light of his brother’s shadow.

But more often the young boy is sitting at the kitchen table in the silence. From outside come the sounds of summer children at play and then the silence is broken by his father’s booming rant about something or other that is of no importance and the young boy sits and listens but he does not hear. He is watching the notes that climb slowly and slide quietly, up and down the stairway of the treble clef. And as his father’s voice becomes intolerably loud, the young boy recites the words that cast a spell, silencing his father’s spitting tongue – tonic solfa; stave; staff; ledger; space; brace; rest; interval; quaver; semiquaver; demisemiquaver; hemidemisemiquaver.

These are beautiful words that have no place in his father’s vocabulary.

And he hears his mother say: “I’m not sitting here if you two can’t be civil to each other” and he’s tempted to smile because he hasn’t spoken a word but he doesn’t smile because that would bring his father’s palm crashing against the side of his face and leave his eardrum ringing, his hearing muffled. Instead, he satisfies himself with the knowledge that there is no one who can disturb the words inside his head because no one can hear their soft hum and their sharp jingle or see the way they wind about each other, one touching the next and that, in turn, caressing the next. Tonic solfa – he loves the warm encouragement of the word tonic, the way it says wellness. It touches him like his mother’s hand touches his forehead when he has a winter fever, with sureness and compassion, telling him everything will be all right. The word is there for him, as she would be. Then there’s the sharper sound of the word solfa. When he sees the word, he sees an axe head and then a very short handle and the axe head is of a gleaming, steely silver. It rests in the comfortable arc of his father’s skull. Around the silver head there’s a pool of quiet blood, fresh but not flowing. His father is sitting calmly in an armchair, the axe lodged in his cranium. He is watching television and the young boy knows his father will never shout again, never raise his hand in anger. The axe has dulled his viciousness and made him content to sit and watch whatever tripe the set beams at him. And everything is peaceful in the house. Tonic solfa, he thinks but he doesn’t forget himself; he doesn’t smile or invite the violence of the real world into the serenity of his imagination.

But sometimes he sits on the cold stairway, wishing his father would strike him, wishing his scalded skin, his shaken jawbone, the burning in his ear, the pain in his head could replace the words and tears pouring up through the dark floor of the sad, brutal world. Believing that one act of acceptance on his part, one rain of blows might wash away the stale stink of anger and frustration that hangs about the house like the smell of rotting fish. He would willingly sacrifice his eardrum or his jawbone or the straightness of his nose or the sight in his eye for an end to this cacophony. And, in the dark of night, the magic words become nothing more than a collection of letters, ineffective and useless. Space; brace; rest; interval; quaver. Mere words.

There is a photograph of Nikolai Kalinnikov in the corridor behind the church altar. It hangs in a space shaded by two pillars, so that his beautiful, smiling face peers from the shadows and seems just beyond reach.

One afternoon, some jostling boys dislodged it from its hook and shattered the glass in the plain timber frame. I volunteered to have the glass repaired and, at the same time, had the photograph copied. I put the copy carefully in the sheet music of Tchaikovski’s Happy is the man in my bedroom.

Occasionally, when by chance I pull that piece of music from the shelf and play it through, I spend a moment or two looking closely at the face of the boy I loved. Love.

Otherwise, I try not to catch his eye in the gloomy church corridor. I prefer to imagine his voice among the voices of the young men hurrying to choir-practice. And, as they crowd into the rehearsal room, I keep my eyes firmly on my roll-book, postponing the moment when I must look up and destroy the illusion that he is still among them.

“Gentlemen,” I say quietly and they fall silent and some of them smile and some are clearly concentrating and some simply wait in that great silence that precedes the music we shall sing together.

Once, when the young boy was a young man and was travelling in his brother’s company, and in the company of other young men, they were crossing a choppy sea in a small sailboat and the waves were high and the night was dark and no one seemed sure if the boat would float or sink. Peter came and sat by him and put his arm around him and whispered: “Do you remember the night we went out in the punt to check the lines and we pretended there was a storm and we rocked the life out of the old flat-bottom?”

“Yes,” the young man says.

“Well tonight is just like that. All these other guys are terrified. You and me are the only ones who know it’s all a joke. We know we’re not going to sink, but let’s not tell them,” and then Peter delivered a conspiratorial pat to encourage him to mask his terror.

“What’s going on?” John, one of the other young men, asks. Even in the darkness his face is a moon of fear.

“Nothing going on, just talking,” the young man says.

“Are we sinking? Is this thing in trouble?”

“No trouble. Peter has it all under control.”

“You’re not just saying that.”

“We’ve been out in worse, him and me, and survived. We’ll be alright.”

“I don’t understand you sea-people,” John says, his voice a little calmer. “I’ll bet you can’t even swim. I’ve heard that about sea-people – they don’t learn to swim; it only prolongs the agony of drowning.”

“I can swim,” the young man says. “I think I swam before I walked. Stop worrying. Peter will get us safely across.”

“I hope you’re right.”

And the young man smiles in the darkness because he has been infected with his brother’s optimism and belief; they have shared something private and personal. Even in the midst of all these other people, the threshing of the waves and the slap and scream of the straining boat-timbers no longer frighten him and he turns his face into the rain and laughs quietly.

Occasionally, when I’m relaxing after choir practice, sitting over a steaming mug of tea, and I hear one of the choir-boys in the corridor singing a pop song he has heard on the radio, I think of the Captain and his love of music.

I was the first one in our town to fall under his spell but it wasn’t his music that cast it, though it was his singing that first caught my attention. I heard him perform at a reading in the back room of a coffee shop. His singing was harmless, in tune but lacking any power or subtlety – bland is the word that best describes it. At the time, he’d sing only his own songs and they, too, were bland, without identifiable tunes and lyrically nothing better than rhyming propaganda. But when he spoke, between the songs, and when he told stories, it was an entirely different experience. The words and images drew you in, taking you to the place about which he spoke. For me, it was like being back at the silent table in my boyhood kitchen. The words he used echoed the words and images I had used to keep my father’s anger at bay. They were different but their effect was the same. They had the power to render the present obsolete and make what he was saying the only reality that mattered.

It was the stories and the characters that peopled them that made his words electric. When he talked of someone he had met in a village square and what that person had said or done, I was there. The sun was toasting my back and the hot sand was caught between my sandaled toes. I was sitting on the low wall of a well. The cup he handed me was filled with clear, cold water and, as I drank from it, I felt a freshness and a cleanliness that made it different from the bottled water of the city bars and cafés.

And it had to do with more than taste or smell. It was filled with the possibilities that suddenly fell into my lap, the thought that everything need not always be the same; the notion that the generals, whose nailed boots dug into our shoulders, would not always be in charge; the belief that freedom was not a delusion. Belief was the key – I had believed in Peter when I was a boy, known that his presence would protect me from violence, silence and noise. And now there was someone else in whom I could believe, a man who was telling me that things could change and would change. His faith was infectious, his words beyond denial.

On Friday nights, after the folk-club had closed, we’d go back, ten or fifteen of us, to the Captain’s house and play music and swap songs. And sometimes, when the Captain sang, I’d strum his guitar and play the harmonica. Once or twice I put tunes to his words and we’d struggle over the compromises of song writing until the sun came up, reminding us that we had work to do.

I was a music student then and the Captain was not yet the man he would soon become. The charisma was there and the stories were there but he hadn’t quite found his direction.

Peter was living in a village just over an hour from the city. He had married and had children, built a boat shed, got into building and repairing boats. He still fished but only to feed his family and to supplement his income from the boat-building. I took him to see and hear the Captain a couple of times and I knew, very quickly, that he was as impressed as I was – more so, even.

After a couple of months, I began to recognise that the Captain’s forte was as an entertainer and the nature of the music he enjoyed was different from the music I love. Music was a means for the Captain; it is an end for me.

I was still intrigued by his stories but I could see an emerging pattern. The characters were becoming less important, the message more so. The group of friends who had gathered around him began to solidify, Peter at the helm. I stayed within the group, more out of habit than out of the commitment that Peter and Jude and some of the others possessed. Perhaps I stayed because Peter was such an integral part of the whole thing and leaving would have seemed, to me at least, like a betrayal.

Mostly, now, when I think of those days, it is as an adjunct to memories of my brother and to the recurring question of whether or not I will ever see him again. He had been my saviour and, as I grew up and moved out of the fear of my father’s pathetic need for control, as I began my musical studies, in the holidays when I went to stay with Peter and his wife and their children and watched him at work in his boat shed, I recognised how much I owed him. And the only thing I could do to repay him was to sit on the porch of his house and play the sad songs he loved on the harmonica.

Now, all these years later, I regularly wake sweating, the source of my certainty gone. I get out of my bed, strip it of its soaked sheets and throw them in the laundry basket before stretching clean, dry sheets in their place. Then I step into the shower and wash away the perspiration of fear and loss. This doing keeps my mind occupied but the warm water in the small, freezing bathroom cannot wash away the sadness that envelops me. And afterwards there come the anger and the other questions.

Who keeps their word?

Even my brother disappeared after the Captain’s death. Yes, I went before him but I kept in touch, by letter and by telephone, whereas he seemed simply to disappear from the face of the earth,

Who considers another more than they consider themselves?

If my love for Nikolai were unadulterated, would I still be here, alive and healthy and working, as his skin and flesh and eyes and hair turn to whatever it is they become before turning into dust.

In the face of failure, our lives are a lie and the lie becomes a road to nowhere. There is a moment when summer turns to autumn and a moment when autumn turns to winter, but we can never identify that moment. All we can do is recognise it after at has happened.

Once, when we were camping in the desert, I heard someone singing a song around the campfire and one of the lines lodged in my head: It’s just that I thought a lover had to be some kind of liar too. It’s one of the few maxims that has remained in my memory from that time.

“Gentlemen,” I say and the choristers fall silent, “before you go home, I want you write down some words.”

The students fumble in their bags, producing pens, pencils, notebooks, tattered sheets of paper.

“We’re ready, sir,” one of them says. “Well, all of us except Popov.”

“I’m ready, sir,” Popov says earnestly.

“Write this, please: ‘The angel said: Don’t be afraid, Mary, for you have found favour with God.’”

Bent heads, pens and pencils moving and then a hesitation as they wait for more.

“Is that it, sir?”

“That’s it.”

“And what are we to do with it?”

“You could think about it.”

“Not a lot to think about, sir,” Popov says. “In fact I’ve thought about it.”

The others laugh.

“And the conclusion you’ve come to?”

“It’s from the Bible,” he says.

There’s further laughter and cries of: “Brilliant.” “Popov the genius.”

“Wow, did you work that out yourself, Valentin?”

The uproar seems to frighten Popov. He is afraid that I’ll blame him for the din.

“I’m not being funny, sir. It’s just that I’m not sure what we’re supposed to get from it. That’s all.”

He looks about him, willing the other boys to be silent.

“You’ve probably got all you’ll get from it – ever,” someone sniggers.

He blushes.

“It’s all right,” I say quietly and I wait for the clamour to die down. “It is, Valentin, as you say, from the Bible, from Luke’s gospel, to be precise: the annunciation.”

“I knew that, sir,” Popov says, too quickly.

“Yeah, you did! We believe you,” the voice comes clearly, sarcastically from the back of the room.

I wait, again, for silence and, finally, it falls.

“All I want is that you think about those words and I want you to listen to this.”

Reaching behind me, I press Play on the CD player and the music begins, Mussorgski’s The Angel Said.

The students listen, enthralled, their faces beaming, already mouthing the unfamiliar tune, listening for the words, wanting to sing. And then the music ends.

“Tomorrow we’ll begin work on that piece. In the meantime, think about those words.”

Notebooks and pens are put away, satchels are thrown over shoulders and the students begin to shuffle out.

Popov stands at my desk.

“Sir.”

“Yes, Valentin?”

“I wasn’t being smart with you, sir, about the sentence you gave us to write.”

“I know that,” I smile. “It’s not a problem.”

“Good,” he says but he doesn’t leave.

“Is there something else, Valentin?”

“Yes, sir, but I don’t know if it’s something I should say to you. It’s difficult, but I need to talk to someone about it.”

I look into his face, the stern face of a nineteen-year-old who is still at sea in the world.

“Would you like to come for a cup of coffee?” I ask. “We could walk to the Chay restaurant. If you like, but only if it suits you to talk today.”

“It suits me, sir, if you have the time.”

Popov packs his bag and I gather my bits and pieces and we walk together to the tearoom on the corner of the street, music huffing from the shadow of a doorway.

“One thing,” I say, as we sit down. “In here, you are Valentin and I’m Andrew. ‘Sir’ stays outside with the accordion player.”

Valentin winces and swallows.

“I’ll try.”

I order two coffees and sour cherry vareniki.

“So, are you enjoying the music?” I ask.

He nods.

“Actually, let me withdraw that question. Let’s leave ‘sir’ and ‘music school’ outside the door and enjoy our food without giving academia a thought.”

Valentin smiles and I’m reminded, for a moment, of the shadowed smile of the man I once knew, the young man dismounting from horseback, elated but cautious about sharing his elation.

The waitress arrives and the coffee and cakes are served.

“Eat up,” I laugh. “These are most definitely not going back to the kitchen!”

Valentin and I eat and drink and make small talk about the goings on in the city.

“It is ok for me to say something to you that may surprise you?” he asks.

“Of course.”

“And…”

He sputters, a crumb of cake catching in his throat, so I pick up his sentence. “And you can be assured of my discretion. What we speak of here remains here and if we speak of it again, then that will be all right, too. This conversation will have no bearing on anything that happens in the choir.”

He nods and breathes deeply, staring at his cup, uncertain, uneasy.

“We’ll have more coffee,” I say, signalling the waitress.

While we wait, I listen to the music coming from the street. The wheezing of the accordion reminds me of my own harmonica playing from twenty years before.

“I played the harmonica,” I say quietly.

Popov looks up.

“Did you, sir? I can’t imagine that.”

“Ah, we all have skeletons in the cupboard. My brother liked me to play it while he worked in the evenings.”

“You have a brother, sir?”

“Yes,” I say with more certainty than I feel. “Just the one.”

“Does he teach music, sir?”

I let the formality go, knowing how hard it is to break a habit.

“No, he builds boats.”

“That’s different. From teaching music I mean. Chalk and cheese.”

“Yes.”

The waitress arrives with the fresh coffees.

“It’s about Nikolai Kalinnikov,” Popov says quickly, once she has left.

“Really?”

“Yes, sir.”

“His death was such a waste of talent…of life,” I say. “He was a bright young man.”

“And great fun.” Valentin’s eyes are suddenly bright and more alive than I’ve seen them before. “I was in love with him.”

I say nothing, not because I’m surprised or hurt but because I’m thinking of Nikolai, remembering his smile and his hair tossing as he hurried along the corridor or crossed the street.

“I’ve shocked you, sir.”

“Good heavens no, not at all. It’s just that I was thinking of his hair, how beautiful it looked, even in death. It was still bright and full of life. I identified him at the morgue and I remember how vibrant his hair seemed. His skin was blue and lifeless, but his hair still looked as though it was waiting for him to get up and run so that it could lift in the breeze. I know that sounds strange but it’s true.”

Popov shakes his head and there is a film of tears about to shatter in his eyes.

“I’m sorry,” I say. “I’m talking too much. I came here to listen.”

“No, sir, it’s wonderful to talk about Nikolai. Some of the other fellows talk about him now and then, but almost as though they’re afraid, as though his death might be contagious. Some just want to forget the accident ever happened but that means forgetting him, denying his existence.”

“You two were close. I hadn’t known.”

“Not in choir. We were careful not to be too close in choir – people talk and snigger. We didn’t want that.”

“I understand.”

“Every day I pass his photograph in the corridor and every day I think about him, sir, and I don’t just miss him as a friend. I loved him. I loved the way he kissed me. I loved touching him. Does this make any sense, sir?”

“It does,” I say, thinking again of the young man on horseback but thinking, too, of Nikolai.

“He liked you, sir. Not that we don’t all like you, but he talked a lot about you.”

“I’m glad to hear that.”

I can feel my own eyes filling, so I drink deeply, the bitter coffee cauterising my senses.

“How do I go on, sir? Does it get any better or does the pain ever get any duller or do I give up?”

“I haven’t seen my brother in almost twenty-five years,” I say. “I have no idea if he’s alive or dead, but I can’t give up. I need to go on believing that I’ll see him again.”

“I thought it would be easier, sir, by now. I thought things would have become more bearable but they just seem to be getting worse.”

“I don’t believe, if you truly love someone, that their loss ever becomes bearable. You learn to accommodate the pain; I think that’s as much as you should expect.”

And then we are silent and each of us in turn sips his coffee, an excuse for avoiding speech, and the music outside stops and, a few moments later, I see the accordion player pass the window of the coffee shop.

“I’m sorry for taking so much of your time, sir. I needed to tell someone. I don’t know what else to say but I’d like if we could talk again, if you didn’t mind, sir.”

“Nothing at all to be sorry about, Valentin. Of course we’ll talk again. I’d like that. Nikolai was a fortunate young man and so are you – you had each other and you will always have each other.”

“Thank you,” he says. “Thank you.”

Outside, darkness has descended. We walk to the street corner without speaking and stand at the spot where Nikolai died.

“Will you pray for me, sir?” Popov whispers.

“I think they shovel my prayers into the bottom of a bucket with the ash from hell,” I say.

He laughs.

The tram rail hums at our feet. We walk together to the tram stop.

“Thank you for the coffee and cakes,” Popov says.

“You’re most welcome.”

A tram judders into sight and eventually squeals to a halt beside us.

“This is mine,” he says.

“Safe travelling. And we’ll talk again about Nikolai, about anything. Nothing will ever change what was between you. That’s a wonderful thing. Love is never truly lost,” I say.

He smiles gently and I can understand what Nikolai saw in him. And then he’s gone and I turn and trudge slowly back towards my flat, avoiding the cemetery, taking the longer way through the evening streets, remembering the sound of harmonica music and something that was a long time ago. And I think of Valentin and Nikolai and I know that soon it will be time for me to think about going home to the warmth of the summer sand.

— John MacKenna

———————-

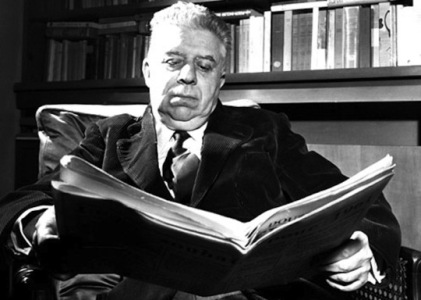

John MacKenna is the author of fifteen books – novels, short story collections, memoir and poetry. He is a winner of the Irish Times, Hennessy and Cecil Day Lewis awards. His novel Clare, based on the life of the English poet John Clare, will be republished by New Island Books in their Classic Irish Novels series in spring 2014. His new novel, Joseph, will be published in autumn 2014, also by New Island.

—

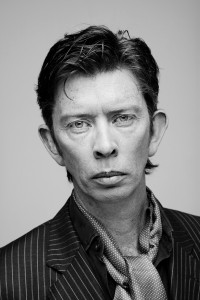

Gerard Beirne is an Irish author who moved to Canada in 1999. He is a past recipient of The Sunday Tribune/Hennessy New Irish Writer of the Year award. He was appointed Writer-in-Residence at the University of New Brunswick 2008-2009 and continues to live in Fredericton where he is a Fiction Editor with The Fiddlehead. He has published three novels, including The Eskimo in the Net (Marion Boyars Publishers, London, 2003) which was shortlisted for the Kerry Group Irish Fiction Award 2004 for the best book of Irish fiction and was selected as Book of the Year 2004 by The Daily Express (England). His poetry collections include Digging My Own Grave (Dedalus Press) which was runner-up in The Patrick Kavanagh Award. His personal website is here.

Dave Smith via The Poetry Foundation

Dave Smith via The Poetry Foundation