Savage Love is an accomplished, funny, and inventive book that readers should rejoice in…By any measure, Savage Love deserves to be recognized as one of the best Canadian books published this year. —Quill & Quire

Before meeting with Douglas Glover to discuss your creative work, it would save time and create a common set of assumptions and a vocabulary for ongoing discussion if you would read through some of his/my published work on writing and the Writing Resource and Craft Book sections on Numéro Cinq. While these readings are not a requirement, it makes sense (and is an act of courtesy) to familiarize yourself with what has already been said and written before asking the same old questions.

Read the rest at University of New Brunswick Writer-in-Residence Meeting Guides.

A glass of wine every day could be the secret to keeping a brighter mind in old age.

Moderate drinking was found to improve memory and learning skills in a long-term study of elderly people.

The research claims that the benefits only begin to emerge after middle age.

The first big (the Toronto Globe and Mail) review of Savage Love, and it’s beautiful, intelligent, well-written and perceptive (if I do say so myself). I could not have asked for a better reading. I am touched. The reviewer knows my work well enough to gauge the differences between my last book of stories and this one, the modulations of theme, and so on. He does a wonderful job of illustrating the emotive range of the texts. It’s rare to get this kind of adult attention, let me tell you.

dg

Douglas Glover is a distinguished member of the tribe of Nabokov. Glover is as gifted a writer as Canada has ever produced and the source of his strength is the ferocious quirkiness of his sentences.

Glover’s new story collection, Savage Love, is an astonishing book only partly because of the loopy and incessant inventiveness of his narratives. The 22 stories range daringly in space and time, taking us from a stomach-turning battle scene during the War of 1812 to a contemporary farm family whose sheer wackiness, condensed into 25 pages, puts to shame any eccentric clan one can think of, whether it be J.D. Salinger’s Glass family or Wes Anderson’s Tenenbaums.

These stories are rich in plot, full of love triangles, murders and descents into madness. The appalling events Glover describes might, in the hands of a lesser writer, seem like mere attention-grabbing sensationalism. Yet his stories leave a genuine emotional scar, because the words he uses are sharp enough to claw into us.

Read the rest at Douglas Glover comes out swinging, prose first – The Globe and Mail.

Packed house, fresh chairs had to be brought in, vivid paintings all around the walls, bad lighting for photos (sorry). The first question in the aftermath was whether DG used psychotropic drugs to write the stories in Savage Love. Answer: Absolutely. (Actually, DG is a total innocent, embarrassingly so; he might as well have been a monk.) (Actually, actually, you should believe nothing DG says about anything.) Post-reading, NC writers Mark Jarman, Sharon McCartney and Gerard Beirne and Sharon’s dog Jack (among many others, and, to be absolutely precise, Jack is not an NC writer yet) adjourned to Alden Nowlan’s former home, now a student pub just off campus, where DG partook of the Barking Squirrel to assuage his shattered nerves.

dg

I dunno. Sometimes I overshare.

Also, this terse description may be a bit confusing. John Metcalf was a bystander and observer. My argument was with someone else entirely — just in case you thought otherwise.

dg

Well, there was the time I got into a fistfight in the bar at the Frontenac Hotel in Kingston, Ontario, during a conference organized by John Metcalf, Leon Rooke and David Helwig. This was in the early 1990s. I still remember the look on John’s face as the bouncers pulled me away. The next time I was invited back to Kingston, the organizers had to pay the hotel a damage deposit before they could book me a room. Naturally, I expect nothing like this to happen in Vancouver as I have mellowed over the years.

via Douglas Glover | Vancouver Writers Fest.

I hate that there are more writers in this country than people who know grammar.

—Attila Bartis, Tranquility

I was listening to this in the car driving to Halifax this afternoon. Could not resist the impulse to share. From Denis Diderot’s Rameau’s Nephew.

I know what you’re going to say. DG should not be allowed near his computer late at night after messing with the Talisker.

dg

…Then, putting his right hand to his chest, he added, “I feel something there rising up–it says to me, ‘Rameau, you’ll do none of that.’ There must be a certain dignity attached to human nature which nothing can extinguish. The most trivial thing will awaken it–something trifling. There are other days when it would cost me nothing to be as vile as anyone could wish. On those days for a penny I’d kiss the ass of the little Hus girl.”

ME: But, my friend, she’s white, pretty, young, soft, chubby–it’s an act of humility that even a man more refined than you could sometimes stoop to.

HIM: Let’s understand each other–there’s literal ass kissing and metaphorical ass kissing. Ask fat Bergier who kisses the ass of Madame de La Mark both literally and figuratively–my God, with them the literal and figurative disgust me equally.

—Denis Diderot, Rameau’s Nephew

Jason Lucarelli, David Winters, and Greg Gerke discuss Gordon Lish, style & life, in a roundtable at The Literarian. Not to be missed, given NC’s commitment to Lish studies and Jason’s two essays here.

dg

When I think of the intersection of style and life, I think mostly of the typical Lish mode, the monologue form. In an interview between Rob Trucks and Gordon Lish, Lish defends his preference for the first-person point of view, saying: “Just to be able to point to a book that was rendered by reason of another kind of device wouldn’t be worth the price in not getting far enough in.” Lish often lectures about “going deep,” about how a writer can never go deep enough. In Tetman Callis’s “The Gordon Lish Notes,” Lish says, “If your work is to work, it must work the way your mind works—the way your mind really works, deep down inside your secret loathsome self.” These ideas, I think, at once dictate the content and the style of the writing produced by Lish and by others who learned from Lish. This daringness, this boldness is reflected in the way these writers often write and in what they are willing to offer up of themselves as they write. There’s often a balancing act—performed through the compositional act of consecution—concerning a secret that, as the poet Mary Ruefle says, “neither hides itself nor reveals itself.” This, I think, is the ethos you’re speaking of, David—the risk of redeeming one’s experience.

Read the rest at The Center for Fiction.

My inaugural reading as Writer-in-Residence at the University of New Brunswick is this Thursday at 8pm in the East Gallery at Memorial Hall. I’ll be reading from Savage Love. This time I get to stretch it out a bit. The readings last week were all pretty short, fifteen minutes or so. I’ve been reading “Light Trending to Dark” and nothing else. Might have time for the amputation scene from “Tristiana” or some such delight. Someone put in a request for “Little Things.”

A special note to my NC supporters: Please do not consume alcohol before or during the performance, also no fireworks, no flaming lighters (remember what happened last time), no throwing footballs, no water balloons, try not to clog the toilets on the chartered buses, someone keep an eye on Rich.

dg

This is the terse lowdown on Hamlet, an exotic pushback against the tea cozy market-driven view of literature and art that rules. It’s about a book no one wanted to publish (see below). But it also starts up a theme for NC, one I’ve been mulling over a while, about art from the margins of culture, sick art, art by the sick, frenzied, chaotic, formed by paranoia instead of form. My model for thought is Christa Wolf’s novel The Quest for Christa T., in which the Heroine suffers repetitive breakdowns and failures as she tries to fit into cultural expectation and common definitions of health and success. Eventually she dies, but dying, in the language of the text, she is vouchsafed a version of beatitude. Then there is Leonard Cohen’s novel Beautiful Losers, which, in its oxymoronic title, says it all. Read the whole Guardian piece and think about it; hell, maybe even buy the book (I know, live dangerously).

dg

In one of the several rejection letters we received when trying to publish The Hamlet Doctrine in the UK (we encountered no such problems in the US), one editor argued that the book was “essentially unpublishable” because it was “a condemnation of the literary culture of my country”. And in one sense, he’s right: our book is an implicit condemnation of a certain, mainstream, version of English culture.

The banal, biscuit-box Shakespeare needs to be broken up and his work made dangerous again. If the authorities really understood what was going on in Hamlet’s head, students might never be allowed to study the text. Hamlet’s world is a globe defined by the omnipresence of espionage, of which his self-surveillance is but a mirror. Hamlet is arguably the drama of a police state, rather like the Elizabethan police state of England in the late 16th century, or the multitude of surveillance cameras that track citizens as they cross London in the current, late-Elizabethan age. Hamlet’s agonised paranoia is but a foretaste of our own.

via It’s time to make Shakespeare dangerous | Books | The Guardian.

As autumn arrives in the Northern Hemisphere, another astonishing, mind-expanding, psychotropic issue wraps up at Numéro Cinq. And we have contributions from Italy, Russia, Sweden, San Francisco, France, and Canada, to name a few. Nothing ordinary, everything fresh and original, a whirlwind of art.

This month features Stephen Sparks and his mesmerizing take on the What It’s Like Living Here series of essays. Sparks’ journey through San Francisco is not to be missed! Then from California to Russia — Russell Working returns to our pages with a memoir about a young American in Vladivostok in 1997; he finds true love and the ghost of Mandelstam. Working reads (and translates) many of the great Russian writers while spending five years living abroad. In a related piece, Russian photographer Valentin Trukhanenko provides lovely photographs of Vladivostok.

Patrick Keane’s powerful essay examines the sources of Emerson’s optimism in the face of tragedy. Numéro Cinq‘s capo di tutti capi, Douglas Glover, reprints his stellar essay on writing, “The Novel as a Poem.” I can say from personal experience this remains one of the most influential and important essays on writing I’ve ever read. Glover’s essay opens with an homage to his great teacher, Robert Day, and it’s with great pleasure that Numéro Cinq publishes the first installment of Day’s new novel, Let Us Imagine Lost Love. Day will publish the novel in serial form, spread out over seven installments in the coming months.

Lawrence Sutin’s follows his earlier novel excerpt in NC with a lovely, thoughtful essay on the music of Vladimír Godár. China Marks returns this month an enchanting series of stitched-thread drawings with embroidered text. Marty Gervais makes his Numéro Cinq debut with three wonderful poems. And Steven Axelrod reviews The Mehlis Report by Rabee Jaber.

Robert Vivian’s haunting, twirling ‘dervish essay’ reimagines language as a form of mesmerizing motion. Diane Lefer reports on teaching writing to paroled prisoners in California. Natalia Sarkissian takes the reader along on a disturbing trip in the Italian Alps.

Reviews this month from Eric Foley (Seiobo There Below by László Krasznahorkai) and A. Anupama (Pinwheel by Marni Ludwig). A photographic series from Abdallah Ben Salem d’Aix plays with color and shadow. R. W. Gray’s movie feature this month is Darryl Wein’s short film “Unlocked.”

Finally, we have poems from Swedish poet Boel Schenlær (translated by Alan Crozier) and David Celone’s translation of Václav Havel’s previously unpublished poem, “The Little Owl Who Brayed.” Celone also provides an essay on translating the poem into English.

A stunning array of work, and another example of the breadth and quality of what’s happening each month at Numéro Cinq. Spread the word!

—Richard Farrell

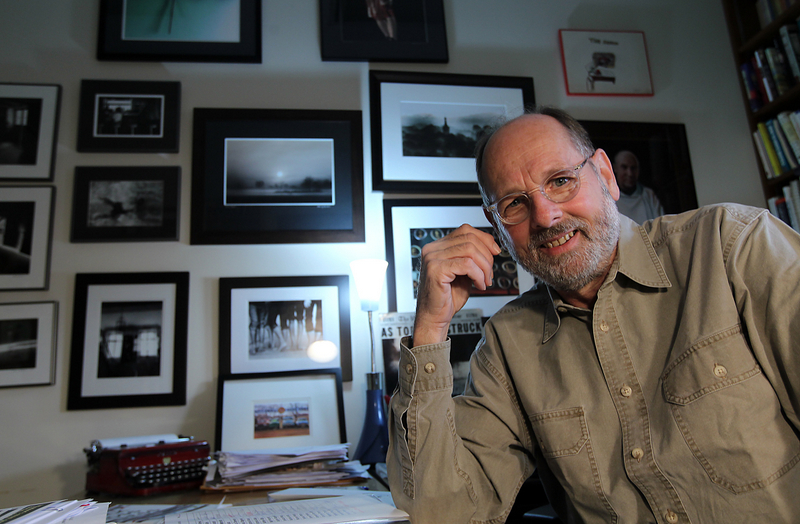

DG was interviewed for Shannon Webb-Campbell’s piece on the UNB writing program in the weekend Telegraph-Journal Salon.

The University of New Brunswick’s current writer-in-residence Douglas Glover, who studied at the Writers’ Workshop with Jarman, now lives in Vermont and edits and publishes the online magazine Numero Cinq, dubbed Fredericton as one of the centres of the writing world.

Glover is the winner of 2006 Writers’ Trust of Canada’s Timothy Findley Award, as well as a Governor General Literary Award winner, and finalist for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. His latest book Savage Love was just released with Goose Lane. The Fredericton publisher has published, or republished, almost all of his work.

Given that the university has the longest continuous writers-in-residence program in Canada, this is Glover’s second stint. The last time he was writer-in-residence was 1988.

Over the years, he has spent a lot of time in New Brunswick, having taught philosophy in the early ’70s at the university’s Saint John campus, and worked as a reporter at the Evening Times-Globe and Telegraph-Journal. He also befriended Alden Nowlan.

While Glover is in town he is available to graduate students and the community to talk about writing and publication; this time, the students get to witness him in the midst of promoting his new book.

“Fredericton is a surprisingly central place in my writing life,” says Glover. “It’s a heady and vivid town for writers.”

Moonlight illuminates the dancers

and the whitewashed concrete birdbath by the standpipe

and coiled green garden hose and the liquid amber gum tree

and the tree nursery under the chicken-wire frame

that keeps out rabbits and deer.

— from “Dancers at the Dawn” in Savage Love

Here is a picture of the birdbath that appears in Savage Love. You can’t see the standpipe, and the tree nursery is gone, but the liquid amber gum is behind the birdbath. I’ve probably said this before: the farm is in southern Ontario, about 20 miles north of Lake Erie just outside a little town called Waterford.

Hives are brought onto the farm during the growing season.

Hives are brought onto the farm during the growing season.

Field tomatoes, note the wastage, a fact of modern agriculture — many of these are perfectly good tomatoes that can’t be sold in the current market.

Field tomatoes, note the wastage, a fact of modern agriculture — many of these are perfectly good tomatoes that can’t be sold in the current market.

—dg

DG @ Bryan Prince Bookseller in Hamilton

DG @ Bryan Prince Bookseller in Hamilton

Stayed at the farm Wednesday: NC poet Butane Anvil (aka Amber Homeniuk) drove us to Hamilton for the Bryan Prince Bookseller event. Scotch at the Snooty Fox first, then reading.

DG at Words Worth Books in Waterloo

DG at Words Worth Books in Waterloo

The excellent publicity person at Goose Lane Editions, Colleen Kitts (bless her heart) sent DG a bottle of Scotch for the Words Worth event in Waterloo. Somehow the Scotch briefly resided in a bin of childrens’ books but was subsequently rescued and put to proper use. David Worsley, co-owner of the bookstore, gave the best bookstore introduction DG has ever heard and then proceeded to ask acute and intelligent questions in the aftermath. Jonah was there with friends and housemates. Also NC playwright Dwight Storring and Kim Jernigan, former editor of The New Quarterly, and Pamela Mulloy, the current editor. Prior to the reading, DG partook of Barking Squirrel beer at the Works next door. After, there was more Barking Squirrel. A good time was had by all.

DG, Catherine Bush, & co-owner David Worsley @ Words Worth

DG, Catherine Bush, & co-owner David Worsley @ Words Worth

Photos of the Toronto launch Tuesday evening at This Is Not A Reading Series in the Gladstone Hotel, hosted by Marc Glassman. Melissa Fisher (photos and essays on NC) took the first two photos with her camera, former NC Contributor Cheryl Cowdy took the last two. Packed house, SRO. DG did an impromptu aphorism contest and gave away a free copy of Savage Love. Catherine Bush showed her book trailer and conducted an Accusation Chorale. In the last two photos: Mark Medley, Book Page Editor at the National Post, Catherine Bush and the inimitable DG, being, well, er, inimitable. After: pleasant painfulness in the wrist from signing books.

There were lots of NC people including Contributing Editor Ann Ireland, Contributor Eric Foley, Michael Bryson, Stephen Henighan, Karen Mulhallen, Melissa Fisher and Cheryl Cowdy (have I forgotten anyone?).

dg

(Reuters) – An argument over the theories of 18th century philosopher Immanuel Kant ended in a man being shot in a grocery store in southern Russia.

RIA news agency quoted police in the city of Rostov-on-Don as saying a fight broke out between two men as they argued over Kant, the German author of “Critique of Pure Reason”, without giving details of their debate.

Fredericton Airport, Monday morning

Fredericton Airport, Monday morning

Detroit from the Windsor side of the Detroit River

Detroit from the Windsor side of the Detroit River

Dan Wells, Publisher at Biblioasis

Dan Wells, Publisher at Biblioasis

DG started his Savage Love book-launch reading tour (along with his co-launch touring partner Catherine Bush) at the Biblioasis Bookstore in Walkerville, the historic Windsor, Ontario, distillery district, still thriving, the air full of the yeasty smell of rye whisky in the making (delightful miasma). The bookstore is at the corner of Gladstone and Wyandotte, the Biblioasis publishing house offices in the basement, the Lorelei Bistro next door (dinner was Lake Erie perch caught off Wheatley — for the sake of tradition, I always order Lake Erie perch when near the lake). Two blocks down Gladstone you come to the riverside park and a vision of America’s largest and most famous bankrupt city. You will recall that Biblioasis published my last book, Attack of the Copula Spiders. I hadn’t seen inimitable Dan Wells, the publisher, since our launch at the AWP Conference in Chicago the year before.

Marty Gervais, whose poems we published in the current issue, was there. Also André Narbonne, whom I included in one of the Best Canadian Stories collections I edited. And Karl Jirgens who edits Rampike Magazine. Also my mother’s neighbours from years ago, the Greenslades, whom she still phones now and then for advice about chickens.

The talk at dinner was about how Detroit is contemplating selling off the trove of paintings at the Institute of Arts to cover its debts. In the past, the only reason I went to Detroit was to look at the art, driving through blocks and blocks of devastated urbanscape to get there. There is a huge Diego Rivera mural. We were wondering how they were going to move that sucker.

Great, responsive crowd at the reading including the guy in the front row at my feet who got so into the RHYTHM of what I was reading that he clearly started to laugh about a second BEFORE the punch lines.

dg

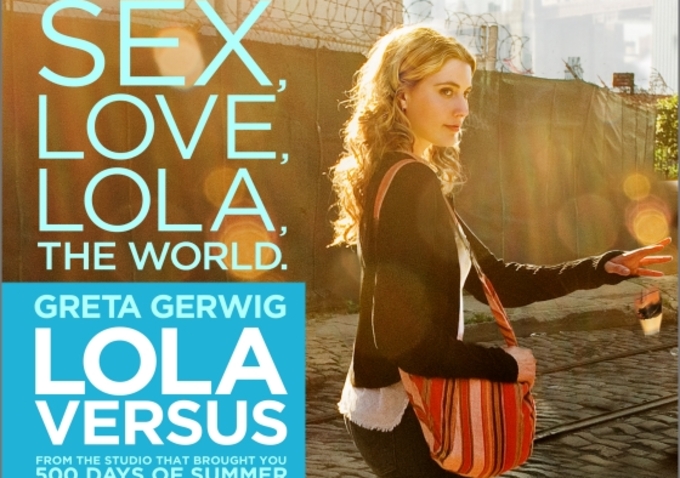

Daryl Wein’s short film “Unlocked” is itself an experience of trauma as it follows a teenage girl who is already negotiating a difficult tension between the bored surface of her teen life, listening to music and sitting around, and the inexpressible experience she is having with a mother who has cancer. Though her friend tries to reach her, even tries to go to the hospital with her, Wein’s protagonist is having none of it. She wants the surface and the depth to keep a discrete distance. She appears to long for normalcy more than anything — louder music and dancing to avoid the incoming messages on her phone — and is willing to separate from reality to keep at least the appearance of that.

The man with the clipboard she meets on the street who suggests she give to charity is a gate keeper who offers her a chance, for better or worse, to bring surface and depth together. Truly, we can’t be certain he is not charitable, but the van and the brusqueness, the rather scripted tone to his own story about a mother with cancer all point to her being duped for his peculiar pleasure.

She is drawn along and through the violence by the possibility of doing something, doing her part, helping children or others in need or even the hope that she might herself make sense of the senselessness of her mother’s cancer. We are forced to sit idly by with dread and a sense that she is searching for something other than sacrifice, something more like mercy.

It’s the final scene which sticks with me, as she walks down the street transformed. She weeps, bare to the world. Not that this excuses the actions of the man in the van, but this outer transformation seems to at last signify, at last create meaning for her around the pain and suffering she has been experiencing but denying.

It is a transformation that recalls for me the transformation at the end of Nadine Labaki’s gorgeous film Caramel where one of the minor characters who has been struggling with a very different type of repression throughout also gets a radical shearing and walks down the street also not recognizing herself. I considered posting that clip, but out of context that would be its own violence. See the film and you’ll see.

Though I am new to Wein’s work, there’s a certain impulsiveness to his characters that compels me: they are creatures of action and tragic victims to their own heroic gestures.

Lola, the protagonist in his film Lola Versus, overwhelmed by a party scene with two of her ex-boyfriends and her best friend who is dating one of them, has an emotional explosion and storms out, but leaves behind anything generic when she grabs a large block of cheese off the food table on her way, holding it in the air as a triumph. Cheese as an exit strategy. These are the kinds of characters that invite emulation and leave me wanting for a good party with a generous cheese plate.

— R. W. Gray

1. I live in a virtual world outside my real country and in a place where I get my mail addressed to another place entirely. For lack of a literary community, I invented one: the online magazine Numéro Cinq. It started out as a student blog for a class I taught, then it became a literary blog, then it became a magazine. It keeps shedding its skin. It’s a community. I have re-found old friends, formed new friendships, become a patron for new writers, resuscitated the forgotten, changed people’s lives for the better and made myself a very busy person.

Read the rest via Five Things Literary: The Virtual Literary World, with Douglas Glover | Open Book: Ontario.

This is the beginning of things, the Ur-essay, the thought-lode out of which most everything else I have written about literature has evolved. It was written in the late 1980s and so, to an ever so slight extent, is a period piece. It forms the centre piece of my book of essays and memoir Notes Home from a Prodigal Son (Oberon Press, 1999). The ideas here expressed evolved out of my philosophical background, long reading, and the lessons I learned during my time at the Iowa Writers Workshop. I mention specifically the novelist Robert Day (who now contributes mightily to NC), but I would be remiss if I didn’t also recall the influence of the late Claude Richard, who was a visiting professor from the University of Montpellier at the time.

I reprint the essay here because the book and the essay were both published long ago; such is the nature of readership that older things fall out of the line of vision. But in fact this essay (and Notes Home from a Prodigal Son), along with The Enamoured Knight and Attack of the Copula Spiders and my long essay “Mappa Mundi: The Structure of Western Thought” form a consistent, coherent and elaborated system of thought about writing, criticism and philosophy.

dg

—

…there is an other [irony] besides the irony of the learned man; there is the poem, in the sense that it is rhythm, death and future.

— Julia Kristeva

1

The best writing teacher I ever had was a Kansas cowboy named Robert Day who showed up at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop as a last minute, one-semester replacement for a sick colleague in January, 1981. The first day of classes he strode into the room wearing Fry boots, jeans and a checked shirt. Without saying a word, he picked up a piece of chalk and wrote across the full length of the blackboard in huge looping letters: REMEMBER TO TELL THEM THE NOVEL IS A POEM.

At the time, Day had only published one novel, a book called The Last Cattle Drive. He was a tenured English professor at Washington College in Maryland. He was a past president of the Associated Writing Programs. As a young man, he had worked at G. P. Putnam’s in New York and could recall for us the excitement over the publication of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. Summers he went back to western Kansas where friends ran a borderline ranch. He kept a horse there, a horse which at various times had eaten loaves of bread through the kitchen window, or Day’s hat. All summer long he would hand out with his friends, their cattle and his horse.

That semester we read Queneau, Musil, Rulfo, Achebe, Nabokov, Tutuola, Abe and Marquez. Day did not tell us what he meant — REMEMBER TO TELL THEM THE NOVEL IS A POEM. Maybe he forgot. Half-way through the semester he read the second draft of my novel Precious, three hundred typed pages of plot, dialogue and scene that stubbornly refused to come alive. I still have the notes I made during our conference, fifty-four words. It took less than fifteen minutes. But like a skilled surgeon he had opened the novel up for me and shown me its heart still beating, its bones, nerves and veins.

He taught me four basic devices. The first was what he called the language overlay. My first person narrator was a newspaperman, he had printer’s ink in his blood. Day said I ought to go through the novel, splicing in words and images, a discourse, in other words, that reflected my hero’s passion for the newspaper world. So, for example, Precious now begins: “Jerry Menenga’s bar hid like an overlooked misprint amid a block of jutting bank towers…” Or, in moments of excitement, the narrator will spout a series of headlines in lieu of thoughts.

Second, Day taught me about sub-plots. The main plot of a novel, he said, is like a pioneer wagon train moving across the prairie. The sub-plot is like the Indians coming in out of the hills to attack from time to time. The pattern of the sub-plot must reflect or parallel the pattern of the main plot, Day said, just as the gene inside a cell contains the pattern for the whole body.

Third, he showed me how to use background and revery. My protagonist must have been somewhere before the novel began, he must have a story to tell that will give texture and depth to his thoughts and, by extension, to the narrative. In Day’s words, he wanted me to “give the novel a memory.” Once again, the background must reflect or parallel or bear the seeds of the main action. A revery that does not bear a relation, in pattern, to the main plot is wasted. It diffuses the reader’s attention. It makes the book foggy and boring.

What this means in practice is that far from being “loose and baggy monsters,” to use Henry James’s phrase, in which the author has room to digress, expand or linger, a good novel is a tight, formal production with very few wasted words.

Finally, Day told me how James used the confidante device to modulate the weight of a given speech. In Precious, I had two secondary characters who were both close to the hero. What if I created a pattern of giving and withholding information? What if I made one of the secondary characters the hero’s confidante, the person to whom he told his secrets? He could then maintain an ironic distance from the other, giving opportunities for lightness and humor. The reader would sit up and pay attention when the confidante was on the scene.

Day then lied and told me I could splice all these changes into the novel in three weeks. Actually, it took me five months, and I rewrote the thing from beginning to end. I remember those months as being the best time of my life; the woman I lived with then says otherwise. She says she never remembers me being more miserable. What that means, really, was that the work was hard but also amazingly exhilarating.

What I had learned was far more than a collection of four devices. I had learned a secret about writing stories, novels and poems. Also painting pictures and composing symphonies. I had learned that a novel is not a string of seventy-five thousand words, all different, all pressing the plot forward. If you think about it, the stories of most novels can be told in a page or two of summary. Then imagine me trying to stretch that summary over another two hundred and ninety-eight pages.

Or, to use an image I had carried in my head through two earlier failed novels, think of a novel as a bridge thrown across a bottomless gorge with nothing to support it from one end to the other. In my mind I had to get a running start and write fast for fear of not making it across. I wrote my first novel in six weeks in a state of terror. As a bridge it was a shambles.

What I had learned was that besides story, plot and characters, the novel needs patterns. That in fact the story, plot and characters don’t begin to come alive until they are submitted to a pattern. I had made a common mistake. Before Robert Day, I had assumed that a novel’s “aliveness” depended upon its verisimilitude, i.e. how closely it resembled what we call real life, whereas in fact it depends upon patterns. I think this is what Day meant when he wrote REMEMBER TO TELL THEM THE NOVEL IS A POEM. He meant for us to notice that, like a poem, the novel should be seen as an arrangement of materials of which one, but only one, is the story. This patterning is the poetic quality of prose.

2

In a poem it is much easier to see the patterns. We’ve all had to map out sequences of stressed and unstressed syllables, the ABBAs of rhyme, the internal rhymes of alliteration, the surprising anti-patterns of sprung rhythm and free verse. We’ve all dissected extended conceits, noted the effects of diction and imagery. These are the things we focus on in a poem. Narrative, story and verisimilitude are secondary to the poetry of poetry, by which I mean the effect of patterns.

With novels and stories, the reverse is true. We tend to read a novel first for plot and character and the narrative’s relation to reality, what post-Saussurean critics call its “aboutness,” and only secondarily, if at all, for pattern. This is a little like Ludwig Wittgenstein’s duck-rabbit argument. You know how you can draw a little circular figure with an elongation here and a dot there. If you squint your eyes one way, you can see it’s a rabbit with long ears. But if you squint another way, it becomes a duck with a protruding beak. With poems and novels, you can read for pattern or you can read for aboutness, depending on how you squint your eyes.

It happens to be the case, though, that we rarely read novels for patterns. One reason for this is that the novel’s very aboutness gets in the way. It is the easiest and most natural thing in the world to read a novel for plot and character. In fact, in most cases you have to read for plot and character in order to situate yourself, as an observer, in the world of the novel. The shift of focus, the new squint, if you will, from plot to pattern only happens on rereading. A good reader, as Nabokov wrote in his essay “How to Read, How to Write,” is a rereader.

When we read a book for the first time the very process of laboriously moving our eyes from left to right, line after line, page after page, this complicated physical work upon the book, the very process of learning in terms of space and time what the book is about, this stands between us and the artistic appreciation. When we look at a painting we do not have to move our eyes in a special way even if, as in a book, the picture contains elements of depth and development. The element of time does not really enter in a first contact with a painting. In reading a book, we must have time to acquaint ourselves with it. We have no physical organ (as we have one in regard to the eye in a painting) that takes in the whole picture and then can enjoy the details. But at a second, or third, or fourth reading we do, in a sense, behave toward the book as we do toward a painting.

When Nabokov makes a distinction between “what the book is about” and our “artistic appreciation” of the book, he is separating our reading of the subject, story and characters — the book’s aboutness — from our appreciation of the book’s so-called artistic qualities, the details we would notice if we looked at a novel the way we look at a painting.

Nabokov assumes that we all look at paintings for more than the resemblance they bear to old dead people in funny clothes, for more than romantic seascapes and sunsets. He assumes that we see, for example, Whistler’s mother as something other than an elderly lady in a plain black dress and that we know, perhaps, that the painting of Whistler’s mother was originally titled “Arrangement in Grey and Black” and that when Whistler talked about painting he would say, as he did in a letter to his friend Fantin-Latour:

…it seems to me that color ought to be, as it were, embroidered on the canvas, that is to say, the same color ought to appear in the picture continually here and there, in the same way that a thread appears in an embroidery, and so should all the others, more or less according to their importance; in this way the whole will form a harmony.

Whistler is talking about patterns, patterns of color that exist over and above and through the subject of the picture, its aboutness. And when Nabokov talks about “artistic appreciation,” he is talking about appreciating the patterns of the novel in the same way, the repetition of certain verbal events or structures in a novel like the colors in a painting. This is precisely the way we appreciate poetry, where it is, as I have said, much easier to see that sounds and words are like oil paints or, for that matter, like notes in a piece of music.

3

Other ages and times have provided writers with pattern books, with instructions on rhetoric and composition. They put names to commonly used devices: paronomesia, periphrasis, prosopopoeia. Even in the 1920s at the University of Toronto’s Victoria College, my aunt was taught to write, to compose sentences, by translating back and forth from Latin to English. But no one teaches composition any more except in remedial programs to students who patently can’t write at all.

Instead we teach creative writing with the emphasis on “creative” (which, I guess, implies that there is “uncreative” writing as well, though I have never seen it). At Iowa, outside of Robert Day, teachers tended to urge us to “write what you know.” If we managed to do that, they said, whatever we wrote would come out all right. Ernest Hemingway, that most brazen of liars, once wrote, “All you have to do is write one true sentence…,” sending generations of his competitors chasing vainly after a will o’ the wisp reality. Why people choose to believe what he says about writing and not what he says about his manliness is a curious instance of intellectual willfulness and self-deception.

In university English departments, on the other hand, students are taught criticism — Arnoldian, Freudian, New, Structuralist and Post-Structuralist, etc. Archetypes, symbols, influences, foreshadowing, metaphor and theme. Academic critics tend to see a novel as full-blown, not something built; as something found, not constructed. Academics are romantics — they see, or prefer to think they see, romantic intention in a novel as opposed to the bricks and mortar. I tried to tell a friend of mine, a person partway through a PhD. in English, what I meant by a pattern in a novel. She said, “Well, we call that recurring imagery.” A singularly bloodless phrase. But fair enough. Yes, that is sort of what I mean.

But why does it recur? And who made it recur? And is that all there is to it? Does the phrase “recurring imagery” help a writer? Academic critics generally see recurring images as evidence of a point the author is trying to make, part of the aboutness of the work. Deconstructionists, on the other hand, look for recurring images that the author may not have intended so as to “deconstruct” the aboutness of the work. In either case, they are wedded to thematics, to aboutness, to truth. Write what you know, throw in a little recurring imagery, and it’ll come out right. That’s what the creative writing schools and the English departments teach us.

In general it’s not terribly bad advice. Many writers get by with no other. Every writer borrows to a greater or lesser extent from the real world the images which he or she deploys in his or her novel. Every writer who has read significantly has an instinctive feel for rhythm, pacing and the repetition of images. But to go through life believing “Write what you know and throw in recurring imagery” is like going through life believing in God and free enterprise — it leads to a conservative and narrow view of life and art.

4

Pattern is an ambiguous word and I want to keep it that way. Writing a novel, Faulkner once said, is like a one-armed man nailing together a chicken coop in a hurricane. It helps to be open-minded and undogmatic about the rules of the operation.

Experience itself rests on our ability to recognize patterns — Forms Plato called them — in the sensory flux. A pattern that does not repeat itself is not a pattern, it is chaos, or it is something like God, or it is nothing. And the ability to recognize patterns is tied up with out ability to remember. Pattern, repetition and memory are the foundations of consciousness.

The same happens in a novel. On a very rudimentary level the author depends on pattern, repetition and memory to give the reader confidence in the world of the book, what we call verisimilitude, the quality of seeming to be real. In Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Anna appears on almost every page. Anna is a pattern, a group of words and characteristics that repeat. If Tolstoy had changed Anna’s name, age, hair color and social background every chapter or so, we would throw the book down in disgust.

Pattern can mean a model or design upon which something else is constructed. Or it can mean the systematic repetition of certain design elements as in the pattern in wallpaper.

Pattern can, for example, refer to something large such as a plot. All romances are based on, say, the model boy meets girl, boys loses girl, boy gets girl. We also say there are no new plots under the sun. And we refer to coming-of-age novels, which have plots based on myths and rites of passage, or adventure novels, which are based on the quest model. What we call genre is a sort of pattern.

But pattern can also refer to something minute, a device such as, say, the list or the epic simile or even the structure of a sentence. Here is Nabokov talking about Flaubert’s Madame Bovary:

Gogol called his Dead Souls a prose poem; Flaubert’s novel is also a poem but one that is composed better, with a closer, finer texture. In order to plunge at once into the matter, I want to draw attention first of all to Flaubert’s use of the word and preceded by a semicolon. This semicolon-and comes after an enumeration of actions or states or objects; then the semicolon creates a pause and the and proceeds to round up the paragraph, to introduce a culminating image, or a vivid detail, descriptive, poetic, melancholy, or amusing. This is a peculiar feature of Flaubert’s style.

Now, though the actual number of usable patterns may, for practical purposes, be infinite, we always choose to use a finite number in any given piece of writing. This finite number of further reduced by the fact that many of the patterns are repeated throughout any given work. The more patterns a writer knows, however, the better his or her chances of being published, being read, or of writing a masterpiece that will endure. The way a person learns patterns is by reading; literature is an encyclopedia of patterns and devices.

Though it is possible to invent a pattern that no one has ever used before, originality in a writer generally amounts to an ability to vary the pattern in fresh ways. One might, for example, decide to use Flaubert’s semicolon-and sentence pattern in a contemporary rites-of-passage novel set in Montreal’s Jamaican emigre community. The pattern would be Flaubert’s, but the variation, the unique application, would be the author’s own.

Repetition, as I have said, is also a pattern. But it is a pattern of a different order, perhaps the pattern of patterns. To me, it is the heart of the mystery of art, of novel-writing. Without it, the novel becomes a strung-out plot summary.

I have tried to think out why repetition is appealing, why it is aesthetically pleasing as a pure thing. I think there are two reasons, or sorts of reasons. The first is essentially conservative — repetition is allied to memory, to coherence and verisimilitude.

The second is biological or procreative or sexual. Repetition creates rhythm which on a biological level is pleasurable in itself, the beating of our hearts, the combers rolling up on a beach, the motion of love. This is the sort of thing Lyotard is talking about when he writes about “intensities” or patterns of intensities in his book Économie Libidinal, or what the Spaniard Madariaga meant when he talked about the “waves of energy” in Tirso de Molina’s El Burlador de Seville.

In Anna Karenina there are two sub-plots: Levin’s marriage and Anna’s brother’s marriage. The novel actually begins with a sub-plot scene — Anna’s brother banished to sleep in his study for having an affair with a maid. These subplots are not simply tacked on. They repeat the marriage theme of the main plot, Anna’s marriage. Anna’s brother’s marriage is, like her own, a marriage on the rocks because of infidelity. Levin’s marriage is, by contrast, dutiful and steadfast.

Tolstoy created three identical patterns which twine and leapfrog and reverberate through the novel. Of course, the details, the contents, are different (this is one sort of variation); and, in the case of Levin’s plot, the structure, the pattern, is inverted, a positive to the negative of the other two plots (repetitions of abstract structures such as plots or relationships can vary in three ways — congruence, contrast or inversion, and the tree in the seed).

References to plot and subplot form a kind of rhythm in the novel. This rhythmic repetition of structures has something to do with what we call pace. As each plot comes round again for scrutiny by author and reader, it is like a new wave of energy, a drum beat. Anna’s story is the melody; Levin’s is a kind of booming base note thudding in counterpoint to Anna’s; Anna’s brother’s rhythm is lighter, more frenzied and comic. Or they are like Whistler’s colors, threading through a painting, darker, lighter, heavier, fainter.

There is another sort of repetition in Anna Karenina, one more mysterious yet. Just after Anna meets Vronsky, there is a train accident. A station guard, either drunk or muffled up too much against the cold weather, fails to hear the train approaching and is crushed to death. This station guard returns in Anna’s thoughts over and over again. He begins to inhabit her nightmares. He even migrates into Vronsky’s nightmares — transformed now into a dreadful-looking little man with a bedraggled beard, bending over a sack, groping in it for something and talking in French about having to beat, to pound into a shape a piece of iron. At the end of the novel, Anna sees him again just as she throws herself beneath the wheels of the train: “A peasant muttering something was working at the iron above her.”

Obviously train imagery is repeated as well, at the beginning and the end. Why? Coincidence? Or is Tolstoy telling us something about the 19th century Russian transportation system? Of course not. Is it foreshadowing? Well, sort of. But foreshadowing is a word I don’t trust. Does this mean Tolstoy is telling us ahead of time that Anna is going to die in a train accident? I think not. I think there is some other motive at work, that the repetition of trains and bedraggled peasants, this bookending of image and incident, the beginning and the end, has a pleasing quality all its own, symmetry, if you will, a rightness, that is felt and appreciated, not “known.” Overture and coda, rather than prediction. A symmetry that would be lost, say, if Anna drowned herself or beat herself to death with a hatchet.

As a pattern, this terrifying little peasant just seems to pop up. He is just there — and there and there and there. He “means” nothing, except insofar as he is associated by juxtaposition with a larger pattern of trains, death, dreams and Vronsky. Somehow he manages to accrue all the potential horror of that pattern. He reminds us, not of the end to which Anna journeys, but of the beginning; so that when she dies, her end is freighted with a kind of fatedness that makes it all the more horrible and pathetic. The peasant is a tiny thread in the tapestry of the novel, a hint of color in the painting, a grace note in the symphony. Nothing more. Yet without him, how much shallower a book Anna Karenina might be.

It is worth noting that certain kinds of patterning, e.g. the repetition of character traits, enhance verisimilitude, while others, e.g. Anna’s peasant, work against it. We might distinguish between these by calling the one sort patterns of verisimilitude and the other patterns of technique. Every novel uses both, so every novel is a little balancing act between the two, or a war. John Hawkes, the experimental novelist, for example, says that “plot, character, setting and theme” (which are generally what I mean by patterns of verisimilitude) are the real enemies of the novel. “And structure,” he adds, “–verbal and psychological coherence — is still my largest concern as a writer. Related or corresponding event, recurring image and recurring action, these constitute the essential substance or meaningful density of writing.”

But, oddly, though patterns of technique and patterns of verisimilitude tend to destroy one another, like matter and antimatter, both are necessary to the work. Depending on how heavily the author plays up one or the other, his or her novel will be more or less “realistic” or more or less “experimental.”

Getting the balances right in any given work is part of the art of art and its mystery and is a skill that cannot be taught. It leads to the feeling, a feeling I have had twice, once with each of my novels, of submission, of loss of freedom, of loss of expressiveness. Because there is a point in the process of writing a novel at which you must submit to the strictures of pattern that you have chosen. All of a sudden, there are things you can no longer fit into this novel, things you must cut, and other things that you must put in. And, of course, with something as complicated as a novel, you never get it right. And you end up wanting to slash your wrists.

As Paul Valéry once said, “A work of art is never completed, only abandoned.”

5

I have already noted that some patterns in novels, those patterns which tend to create verisimilitude, are like the patterns of experience in the world. This is as much as to say that a conventionally realistic novel reflects a certain metaphysics or philosophy of being and knowing. Modern novels of a less conventional sort also reflect a metaphysics, but it is a new metaphysics, a radically new way of talking about the locale of existence.

Vladimir Nabokov, whom I have quoted extensively and who has influenced a whole generation of North American writers (in Canada, at least two Governor-General’s Award winners, Robert Kroetsch’s The Studhorse Man and Hubert Aquin’s Trou de Memoire, owe huge debts to the structural and verbal pyrotechnics of Nabokov’s novel Pale Fire), was an intellectual heir of the Russian Formalists. Formalism was an aesthetic and critical movement that thrived in St. Petersburg and other eastern European cities early in the twentieth century. The Formalists pegged a whole philosophy of language and literature on the split between meaning and signifiers, between aboutness and pattern.

What they did was put a theory to the things painters like Whistler and, soon after, the French Impressionists, and Surrealist poets like Breton, Eluard and Ponge — all the way back to Mallarme (Nabokov sneaks Mallarme quotations into his novels) — had been doing ten, twenty, thirty or more years before. They simply recognized that aboutness and pattern were two aspects of the things we call art and language, and that you could, in fact, have pattern without aboutness.

Since it seem impossible to have aboutness without pattern, a corollary of this is that aboutness is somehow secondary, a poor cousin, on the aesthetic scale of things, to pattern. Nabokov again:

There are…two varieties of imagination in the reader’s case… First, there is the comparatively lowly kind which turns for support to the simple emotions and is of a definitely personal nature… A situation in a book is intensely felt because it reminds us of something that happened to us or to someone we know or knew. Or, again, a reader treasures a book mainly because it evokes a country, a landscape, a mode of living which he nostalgically recalls as part of his own past. Or, and this is the worst thing a reader can do, he identifies himself with a character in the book. This lowly variety is not the kind of imagination I would like readers to use.

This is what the post-Sausurrean critics, recently so popular in Europe and on American university campuses, are saying. Aboutness is old-fashioned, authoritarian, and patriarchal. Signs — read, pattern, poetry — are playful, subversive, and female. How a thinker can jump from a purely logical incongruence — the fact that, apparently, you can have pattern without aboutness but not vice versa — to these strings of value-loaded predicates is marvelous indeed and evidence that the instinct for narrative and romance has not died behind the ivy-covered walls of academe.

Another corollary of splitting the categories of pattern and aboutness is that there is a sense in which pattern itself creates meaning. Or to put it another way, the novel is about its own form. Or every book is about another book, or books. And every work of art is a message on a string of messages which begins nowhere and ends nowhere, to no one and from no one, and about nothing except the field of pseudo-meaning created by previous and future messages. It is all a game of mirrors and echoes. A little dance of images, words, and patterns. The of the Hindus, or all is vanity, all is dust, sure enough.

Keats wrote, “A man’s life is an allegory.” Nothing else. Or conversely, Korzybski says, “The map (read, the allegory, the pattern, the words) is not the territory.” Which is to say, as Jacques Lacan does, that all utterances are symptomatic and that the real is impossible.

6

Form (or pattern) and aboutness (or content, or reality) are the binary opposites of thought. The stance of the modern, whether he or she is a novelist, critic, theologian, or psychologist, is that ontology begins and ends with the former, that so-called reality is a highly suspicious article.

We are pressed back to a position of washed-out Cartesianism: I think, therefore, I think; or more precisely, I think, therefore something is thinking. Structuralists like Levi-Strauss say things like, “There is a simultaneous production of myths themselves, by the mind that generates them, and, by the myths, of an image of the world which is already inherent in the structure of the mind.” Linguistic philosophers like Wittgenstein say, “The world is my world: that is shown by the fact that the limits of language stand for the limits of my world…I am my world.” Except that this “I am” is not the body but language itself.

Reality, meaning, aboutness, the good, God and the self are pushed away into the realms of the unconscious, the unknowable, the unspeakable, and the unfathomable. In a very logical sense, they no longer concern us here as we race toward the end of the twentieth century. To say you are writing “realistic novel” is to commit as much of an intellectual solecism as, say, the Reverend Jimmy Swaggart does when he says God spoke with him before breakfast. The words “realistic novel” can only be spoken by a person who is speaking in the discourse of an earlier age or in parody.

Think of yourself in a room with bare plaster walls and no windows or doors. You have an infinite supply of variegated wallpapers. You paper the room with something in blue with a skylark pattern, then you do it over with angels, then an abstract, decorative pattern.

The first thing you notice is that you can’t see the wall anymore. This is the first effect of language, according to the philosophers and critics. As soon as you begin to use language, describe the world, you can no longer see it. You can only see your description. In fact, since we can’t even begin to describe something without language, then the existence of the wall itself becomes moot.

The second thing you notice is that each layer of wallpaper covers the previous layers. They’re lost, though you know they’re under there. In a sense the old wallpaper, the past, becomes part of the reality you are describing with each new layer of wallpaper. And sometimes you wake up in the morning and wish you still had the skylarks. You might even try to scrape some of the new wallpaper off. But that only makes a mess.

All you have is the design of each successive layer of wallpaper, and, just possibly, the shape of the room, its broad outlines, its cubic form. Life and art are a little like this. We only see the current wallpaper, remember bits and pieces of the old in the form of myths and memories of memories and fragments of discourse which no longer “mean” what they once meant. And, if we’re lucky, we intuit, or think we intuit, some vague outline of the something which may or may not be the room or the womb of reality.

To be a writer is to write with this knowledge, that the wallpaper is wallpaper and not the room, walls and plaster. It is to have that quality which Keats said went to form a man of achievement “especially in literature and which Shakespeare possessed so enormously,” what he called Negative Capability — “that is when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

Negative Capability is the artist’s ability to suspend belief in any particular conceptual system (or wallpaper) or to see the conceptual system as pattern, as opposed to reality, as material in itself to be juggled and juxtaposed. Or, to put this another way, aboutness is illusory. What we see as aboutness the artist sees as just another pattern or part of a pattern. Or again, everything is pattern, infinitely plastic and malleable. A person who believes in a particular conceptual system believes that everything can be explained by reference to that conceptual system. Whereas the artist sees the pattern and feels the mystery that looms beyond the pattern.

The truth of the matter, everything that seems supremely important in life, begins when the talking, writing, painting, sculpting, filming and singing of discourse stop. All talk or art that says it’s telling you the truth about life is second rate. Of course, you can write something second rate that’s very popular, even quite good, for all these categories are relative. But great art is pattern over mystery, it is juggling words over whirlpools of silence.

7

In the extended sense, this view of language, life and art can seem exceedingly austere, if not forbidding and bleak. “The ultimate goal of the human sciences is not constitute, but to dissolve man,” says Levi-Strauss. (Just as Nabokov says that one of the functions of a novel is to prove that the novel in general does not exist.) Few of us can help feeling a nostalgia for the old ways, or what we think are the old ways, of talking. For ancient beliefs. For certainty and immortality. For familiar stories with plots and characters and recognizable locales. For adventure, romance and magic.

A lot of fictional, intellectual and political hay has been made out of this nostalgia, a nostalgia expressed, say, in the phrase “breakdown of values.” When an old way of talking disappears, many people are forced to apply narrative in order to explain it to themselves. They often feel they have a stake in the old way. They invent metaphors and analogies — machine breakdowns, erosion, war, disease — to make themselves feel easier. And to sell books.

You can see where nostalgia led Levi-Strauss in his wonderful autobiographical novel Tristes Tropiques. The annihilation of the self, of meaning and aboutness, by structural anthropology drove him into a quest for theological support, which he may or may not have found wandering amongst the Buddhist temples of the Far East. Or think of Sartre turning from the barrenness of existentialism to the warm, sloppy infantilism of Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book. Or of Michel Foucault leaving his university office every afternoon to pursue a gruesome and self-destructive quest through the bath houses of New York until his death from AIDS.

One can look at people like Sartre, Foucault and Levi-Strauss as contemporary monks whose intellectual vigor and honesty led them to the conclusion that God, man and reality cannot be reached through words. (On December 6, 1273, at the age of fifty, Thomas Aquinas suffered something like a nervous breakdown and never wrote again.) That, by analogy, telling a story is a logically impossible project. That our only recourse (save for silence) is to take a step willy-nilly into narrative, or faith — Keat’s Negative Capability is something like Kierkegaard’s Leap of Faith. It can’t be done — all the critics and philosophers tell us — but some of us will jump in anyway and start the story “Once upon a time…”

In this regard, the American Catholic novelist Walker Percy once wrote:

…a novelist these days has to be an ex-suicide. A good novel — and, I imagine, a good poem — is possible only after one has given up and let go. Then, once one realizes that all is lost, the jig is up, that after all nothing is dumber than a grown man sitting down and making up a story to entertain somebody or working in a “tradition” or “school” to maintain his reputation as a practitioner of the nouveau roman or whatever — once one sees that this is a dumb way to live, there are two possibilities: either commit suicide or not commit suicide. If one opts for the former, that is that; it is a letzte Losung and there is nothing more to write or say about it. But if one opts of the latter, one is in a sense dispensed and living on borrowed time. One is not dead! One is alive! One is free! I won’t say that one is like God on the first day, with the chaos before him and a free hand. Rather one feels, What the hell, here I am washed up, it is true, but also cast up, cast up on the beach, alive and in one piece. I can move my toe up and then down and do anything else I choose. The possibilities open to one are infinite. So why not do something Shakespeare and Dostoevsky and Faulkner didn’t do, for after all they are nothing more than dead writers, members of this and that tradition, much admired busts on the shelf. A dead writer may be famous but he is also dead as a duck, finished. And I, cast up here on this beach? I am a survivor! Alive! A free man! They’re finished. Possibilities are closed. As for God? That’s his affair. True, he made the beach, which, now that I look at it, is not all that great. As for me, I might try a little something here in the wet sand, a word, a form…”

—Douglas Glover

Vice: Are plots, or things that stand in as plots in your texts, completely incidental products of language, or is there an underlying scaffolding at any point?

Life is plotproof, muddled, desultory, irreducible to chains of cause and effect. It’s sweaty and rampantly sad. It’s a motion of moments. There’s no line of any kind other than the one that runs from birth to thwarting to death. As a reader, I drop out of a novel or even a short story as soon as I sense that the writer has a scheme and is overarranging things. I’ve had it with the masterminded. That’s just my own prejudice, obviously, but I’m the same way about humor: I don’t want to wait through a setup for the punch line: I want one one-liner after another: I want the upshot, I want everything to feel final from the first, I want the conclusion. I don’t need to know what it took to get there; I only need to know that there’s nowhere else to go. In my fiction, life sweeps over people as they sum themselves up on the fly. There’s no backstory for them to take shelter in. They can’t luxuriate in ancestry and hand-me-down handicaps. They’ve never once felt as if their bodies were earmarked for life. It’s all they can do to just view each other’s ruins and blurt out their apercus in nothing flat. There’s nothing more to it than the fact that in every moment everything’s over all over again. It’s not as if there were something to be had from life. And there isn’t one thing to lead to another, because there’s only ever just one thing—maybe it’s a man rubbing a woman’s feet every night, often for hours on end, the woman keeping her socks on while he rubs, thick socks, happily and athletically striped and reaching almost to the knee, and the man not minding having something to do with his hands, which otherwise would only be falling asleep, because he’s over in Japan teaching business writing to homesick Americans, even though he doesn’t know the first thing about business writing, and the woman is just another American, of appealingly clouded mind and projective hair, nothing else going on between the two of them except for the foot-rubbing, though she is growing on him, but only as if she is literally appending herself to him, and what she’s screaming about at the top of her lungs is either only the fact that she’s in a faraway place but doesn’t feel far away or the fact that just because she means something doesn’t mean anything other than that with any luck she will one day probably get away with calling the man a friend.

—Jason DeYoung

Going off the grid has always been an American aspiration. From the Quakers who fled English persecution, to David Koresh, who vainly hoped to build his own world in Waco, Texas, to that earlier generation of Texans who with the help of the US Army tore themselves away from the feeble Mexican grid, bringing half of Mexico with them, our people have set their faces hard away from the order and authority of others. What could express this ideal more faithfully than the pulps? James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales retail the now quaintly preposterous exploits of a self-sufficient woodsman who, with his loyal Chingachgook, adventures deep into near-virgin forest, where he does unto noble and fiendish redskins as they deserve, and then, after mostly triumphing in this American endeavor, heads for the delectably unknown West, so as to die in sight of the Pacific. Zane Grey’s Riders of the Purple Sage brings its hero and heroine into a beautiful valley whose entrance they seal off forever to save themselves from the murderous lechery of Mormon elders. How convenient; how easy! Once we have escaped the grid, won’t it be dreamlike? “Deerslayer determined to leave all to the drift, until he believed himself beyond the reach of bullets.”

Americans love to believe in happy endings; they will settle for happy interludes. One indication that Gulliver’s Travels was not written by an American is that the fairy-tale lands discovered by its narrator are parodies of, and commentaries on, his own society. How un-American! Irony only weighs us down. This fact imparts to our best nature a kind of nobly hopeful ambition; it likewise enables the “ugly American” side of us to be arrogant and cruel in its self-righteous claims. Emerson did remark, in tune with Gulliver, that “travelling is a fool’s paradise,” but he still believed that “the bountiful continent,” much of which then (1844) remained very much off the American grid, “is ours, state on state, and territory on territory, to the waves of the Pacific sea.” The ours is significant. When Americans go off the grid, they often like to take possession. Hence Emerson’s invitation. Instead of haggling with the eldest son for a share of some shabby old farm shadowed by finitude’s despotism, Americans could survey and plat their own grids, break their own soil, reinvent themselves, and get rich. One stellar reason to get off the original grid is that we ourselves don’t control it, which must be why we’re poor. In new lands, how could new lives not come to be?

Read the rest here. Via Bookforum

—Jason DeYoung

Marty Gervais is a poet, prose writer, photographer, historian, journalist and publisher from Windsor, Ontario. His family is ancient, descended as it is from early French settlers along the Detroit River (in the days when the French owned a vast North American empire stretching from Louisiana to New Brunswick and far to the west — the thirteen American colonies were hemmed in along the Atlantic seaboard). Marty is special to me because he published my first book at his publishing house Black Moss Press. He’s a gifted reader of his own work, also an amiable and hilarious raconteur; I got the full effect during the little reading tour Marty, Sydney Lea, John B. Lee and I did last spring along the Lake Erie north shore (many readers will recall the Extravaganza by the Lake). When you read the first poem “Cathedrals,” remember that Windsor sits across the river from Detroit. When you read the second, remember that Marty was raised Catholic by the nuns and speaks easily if whimsically of angels and such. And when you “The Wedding Dress,” beautiful and aching with human sweetness, remember that he is a family man with a large heart.

dg

—

Cathedrals

They were cathedrals

—these sprawling factories

with frosted glass metal-framed windows

that tilted open to a landscape

of wartime houses and brick schools

—the men, like monks, moved

in slow motion, and my father

in a white shirt and crooked bowtie

paced among them

worried over meeting the numbers

Today, these places lie mute —

edifices of crumbling brick

cracked and broken windows

and the rubble-strewn earth

taking back the 20th century

with trees bursting up

through the busted concrete

Months before my father died

we cruised the empty streets

and picked our way among the ruins

of the old Studebaker and Ford plants

the Motor Lamp on Seminole,

boarded up dry goods stores

and barber shops and fish & chip joints

We stood in the middle of the sunlight floor

of the place where he made headlamps —

an acre of concrete once complicated

by conveyor belts and sturdy steel columns

and he told me of those mornings

walking to work from Albert Road

chomping on an apple

a metal lunch pail tucked under his arm

a skinny boy of 16 having landed her

from the mining towns in the north

a job on the line, a job he’d never quit

till his heart gave out, and now

there are mornings when I pause

before a single building

and peer through a toothwall wall

of broken glass imagining life

on that concrete floor

He told me once how he’d trade

Everything to return to that time

that sweet independence

of youth and a job

and a cheque on Fridays

Guardian Angel

He’s lazy and never around

when I need him

I drive down

to the coffee shop

in the early morning

and find him reading the paper

or talking to the locals

I want to tell him

he’s not taking this seriously

— he’s supposed to watch over me

He shrugs and says the rules

have changed

I can reach him on Facebook

Besides he carries a cell phone

I want to ask how he got this job

Why me? Why him?

Luck of the draw, he shrugs

our birthdays the same

we both have bad eyes

a hearing problem

and can’t eat spicy foods

But where was he in October 1950

the afternoon on Wyandotte

when I was four

and I ran between

two parked cars?

He was there, he says

coming out of the pool hall

to save me

to cup my bleeding head

on the warm pavement

to glare at the driver

who stood in the open door

of his Ford worried sick

that I might die

He was there, he said

otherwise I might not

be having this conversation

and he was there again

when I lay curled up

and unconscious

in the hospital room one winter

swearing at the hospital staff

after bowel surgery

and he touched my lips

with his index and middle fingers

and quieted me

Besides, he’s always there

and there’s no point

having this conversation

— he’s so far ahead

and knows so much more:

a hundred different languages

names of every star

in the universe, the physics

of flying, and the winner

of the Stanley Cup

every year till the

end of time

The Wedding Dress

The first time I saw it

I was six

and sunlight spilled

through the bedroom window

I lifted this limp white satiny dress

from a flattened cardboard box

in the cedar chest

I raised it high above my head

— the fitted narrow waist

with a row of fabric covered buttons

and the invisible side buttons

along the left side seam

I could hear Arthur Godfrey on the radio

in the other room

the kettle’s whistle

I could hear the man next door

working on the roof of his house

I held the dress high above me

fingers marveling at its smoothness

lost in its whiteness

and the full length skirt

cascading gracefully

in alternating tiers of sheer chiffon

when suddenly my mother’s voice

at the doorway told me

it was a summer day like this

It was at the farm in Stoney Point

when she first put on the dress

and how she had gone upstairs

in the room shaded by the front yard maple

and how she remembered

gleaming cars zigzagged in the yard

and her fingers fidgeting

as she slipped on this dress

how the day was hot and cloudless

and how her father complained

there hadn’t been enough rain

and she told me she had waited

forever resting on the edge of the bed

for her mother to come and approve

and how she sat there

staring out the window

shoes resting beneath her

like two sleeping birds

on the hardwood floor

then she heard her mother’s

voice at the edge of the room

the softness of the words

enveloping her in that moment

and she knew it was time

to take the car to the church

its steeple towering above the flatness

of the farm fields

and she wondered then

if it was all a mistake

—Marty Gervais

———————

Marty Gervais is an award winning journalist, poet, playwright, historian photographer and editor. In 1998, he won the prestigious Toronto’s Harbourfront Festival Prize for his contributions to Canadian letters and to emerging writers. In 1996, he was awarded the Milton Acorn People’s Poetry Award for his book, Tearing Into A Summer Day. That book also was awarded the City of Windsor Mayor’s Award for literature. In 2003, Gervais was given City of Windsor Mayor’s Award for literature for To Be Now: Selected Poems. His most successful work, The Rumrunners, a book about the Prohibition period was a Canadian bestseller in 1980 and was re-released in an expanded format in 2010 and was on the top ten Globe and Mail bestseller list for non-fiction titles. Another book, Ghost Road and Other Forgotten Tales of Windsor was released in 2012. An earlier collection, Seeds In the Wilderness, of his journalism appeared with Quarry Press in Kingston. It includes interviews Gervais conducted with such notable religious leaders as Mother Theresa, Bishop Desmond Tutu, Hans Kung and Terry Waite. With this latter book, Gervais photographed many of these world leaders.

Václav Havel via The New Yorker

Václav Havel via The New Yorker

Václav Havel was a hero to my generation, a poet, playwright, and political dissident who stood resolutely against Soviet domination during the final decades of the Iron Curtain, who spent years in prison, and who eventually helped engineer his country’s so-called Velvet Revolution in 1989. I have read Havel and about Havel all my life, it seems, and now it is a special honour to be able to publish in Numéro Cinq a hitherto untranslated Havel poem, “The Little Owl Who Brayed.” This is an amazing coup made possible through the efforts of the poet and translator David Celone who not only translated the poem and wrote an astute essay for us but also contacted Havel’s widow and obtained the necessary permissions for publication of both the translation and the original Czech version of the poem.

dg

.

The Little Owl Who Brayed

Wisdom’s little owl brayed:

“How beautiful is rot’s decay.”

A pine grove bleated low:

“Come on, easy does it now.”

A serpent hissed: “I love graveyard’s bliss.”

A flower extolled:

“Where ambitions pit your soul?”

Pines gushed: “Wise up.”

Flower hissed: “Let it stink.”

“You should never, it’s true,”

calls motherland insistent,

“in twilight’s advancing gloom

be the least resistant.”

Pines shot: “Reason rots.”

Flower shrieked: “Beauty reeks.”

Serpent hooted: “The graveyard

is paradise, so tranquil and muted.”

You should never, I cry,

in our nation’s interest

beneath twilight’s grimace

ever have to resist.

Dig in. Resist. Persist…

— Václav Havel 1977 (translated by D. Celone, with Liba Hladik and Paul Wilson)

/

ZAHÝKAL SÝC

Zahýkal sýc: „Krásné je hnít.”

Zašuměl bor,

že: „To chce klid.”

Zasyčel had: „Hřbitov mám rád.”

Zaskvěl se květ:

„Kam se chceš drát?”

Zahýkal bor: „Rozumný být.”

Zasyčel květ:

„Nechat to čpít.”

„A tak by se neměl věru,”

volá vlast,

postupujícímu šeru

odpor klást.”

Zasyčel bor: „Rozumně hnít.”

Zaskučel květ:

„Krásné je čpít.”

Zahýkal had: „Hřbitov je ráj

a je tam klid.”

A tak by se neměl věru

v zájmu vlasti

postupujícímu šeru

odpor klásti.

Odpor klásti…

— Václav Havel, 1977

§

Václav Havel’s many incarnations led him from poet to playwright, to essayist and dissident, to become the final president of then-communist Czechoslovakia in 1989 before being elected as the first president of the newly formed democratic Czech Republic in 1993. He was jailed for his writing in samizdat (government suppressed and censored) underground publications and for signing Charter 77, a public indictment of the government’s human and civil rights abuses, the dissemination of which was considered a political crime. Notions of peaceful resistance proffered by Charter 77 evolved into what became known as the Velvet Revolution, ultimately toppling the communist regime in Czechoslovakia. During Havel’s nearly four-year incarceration, he continued to write letters and to dream of new scripts for plays. His letters from jail to his wife were subsequently published as Letters to Olga, a fascinating introspective journey of personal snippets, joys and woes during his prison term. Little is known of Havel’s poetry outside of the Czech language and archives of the Havel Library in Prague. His fame revolved around his plays that used absurdist humor to expose the plight of a country and its people oppressed by communist rule. Havel’s political career brought him into the public light, winning him many international accolades and honors for his work as an outspoken proponent of human rights including the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Gandhi Peace Prize, the Philadelphia Liberty Medal, and the Order of Canada. This poet turned playwright turned politician deserves much of our attention as writers and humanists. Yet, his poetry remains a mystery.

The 1970s in Czechoslovakia was an era and place where totalitarian rule under the then communist regime took great tolls on the Czech people. The state normalization politics of quietism backed by strong-armed police efforts and state-led propaganda campaigns attempted to convince the Czech people that silence and tranquility were the traits needed to live in peace and harmony with one another while submitting to the political will of communist rule. The alternative, of course, was jail. Imprisonment for speaking out against the state, including censorship and arrest of writers and artists, exile, loss of work, and loss of educational opportunities for the children of political dissidents became the norm. As a result, the heavy iron hand of the communist regime laid waste to artistic creativity and voice, breeding considerable unrest and dissidence.