Dede Crane writes the anatomy of an affair of the heart in her story “Tattoo,” which is, yes, the story of a tattoo and what that can lead to. Two sisters lounge on a Mexican beach; it’s their last day; the sisters practice their sibling rivalry; Corona beers mark the hours in the sun. A Mexican tattoo-artist, auspiciously named Jesus, plops down beside them and starts his spiel. The narrator has not been lucky with men; she rescues dogs instead; she is acutely aware of stereotypes and the tepid bourgeois agonies of the North American tourist class. Should she? Shouldn’t she? She wants to pay; Jesus considers it a gift. Something is happening. Eventually, there is dinner and more drinking and Jesus ends up carrying the drunken and unconscious sister to their room. And then he stays. What follows is not, as I have somewhat disingenuously called it, an affair — something else, more revealing and innocent, surprising and right.

dg

Late afternoon, we had ordered beer and tortilla chips. Two ahead of me already, my sister thanked the waiter for her third Corona and squeezed the slice of lime down its neck. Our last day in Mexico and she seemed determined to squeeze as much good time out of it as possible.

It was only my second.

I’d had enough of the sun, the salt and my know-it-all sister. I felt like going back to the room, packing for tomorrow, ordering dinner in and finishing reading Donoghue’s Room.

The last of the daytime hawkers were trudging down the beach with the same cheap goods you found in the market, half of them made in China. Yet another one, a backpack slung over one shoulder, was making his way over to us. I sipped my beer and looked right through him at the banana boat about to flip its thrilled passengers into the sea.

“Henna tattoo for your shoulder, ankle, breasta,” the hawker announced in slow but impressive English, all his T’s crossed. He stopped in front of us, blocking the sun for which I was grateful.

“No gracias,” my sister and I said together, a reflex now, like brushing away a fly.

I scooped guacamole onto a chip. Did he say breast?

“My tattoos are the besta, they last longest and do not wash off in the ocean.”

I ate my chip ignoring him. I’d instructed my sister not to respond to hawkers a second time. “It’s like training dogs,” I’d said, “you give the command once not six times or you’re training them to not respond until after six commands.”

“Today, ama feeling generous.” He spoke in such a grand yawning accent that I looked up. Taller than most Mexican men but with the same barrel chest, he had a goatee and bare hint of a moustache. The black curls that blew round a face that made me think of third grade and the boy I’d loved, Freddy Quintana.

“Two for the one price.” He held up his fingers like a peace sign and smiled.

Like Freddy, his cheeks bunched high at their corners when he smiled and his round-cornered teeth gave them the appearance of Chiclets. I used to imagine the sweet taste of Freddy’s teeth.

I was about to break my own rule and repeat ‘no, gracias,’ when my sister said, “Let’s see your tattoos then.” Seeing my expression, she said, “Jim thinks tattoos are sexy.” Jim was my brother-in-law, a mortgage broker and former college football player. “Come on. I’ll pay.”

The hawker dropped to his knees in the sand and swung off his pack. He looked up at my sister with sad gratitude like some sort of beggar.

No, he didn’t. His eyes ran the length of your legs.

My sister was an emergency room nurse. Forty-one, she lived in Denver with her husband and thirteen-year-old son. She’d paid off her mortgage, had a pension plan, an investment portfolio, and international condo shares which was the sole reason I was in a wet bathing suit watching a fleet of bucket-mouthed pelicans fly over the Pacific. Waves crashed on the beach before me while the narrow streets of old Puerto Vallarta, its white stucco buildings and clay tile roofs, raced up the hills behind me.

I lived in Nanaimo on Vancouver Island, in a rental house, and my life savings amounted to two thousand dollars. Never the stomach for a nine-to-five, I grew medical marijuana for cancer patients and painted houses, interiors. I rescued dogs and found homes for them. At any given time I had between three and eight mongrels warming my bed. A dog, I discovered, was more faithful than a husband.

On the beach that day: for the first time in years I had shaved my legs, knowing my sister would have felt embarrassed on my behalf. I’d also allowed her to buy me a pedicure and my toenails were a shiny Bruised Plum. I hadn’t used nail polish since junior high and every time I looked down, my feet startled me, as if they were someone else’s.

The hawker handed us a black binder of sample tattoos and of photos of smiling teenage tourists wearing his product. My sister paid his two-for-one asking price which seemed no cheaper than two tattoos, then picked a lotus flower for the small of her back. He introduced himself as “Hayzeus” was what I remembered, but my sister remembered him saying the English “Jesus.”

She lay down in the sand while he straddled her legs.

He did not straddle me. He sat beside me.

His back arced over her, his bare thigh muscles taut as he pressed a rectangle of paper along her bikini line to transfer the image. Apparently he wasn’t an artist but a professional tracer. He took up his ink bottle and squeezed out not the brownish-orange color of henna but a black viscous line that looked like crude oil. What sort of cheap and unregulated substitute did they use down here? I imagined blood poisoning, raised welts, skin cancer.

When he was done, he told her not to wear her cover up nor sit in her chair until the ink had completely dried. He stood and kneaded his right thigh.

“How’s it look?” she asked me.

It was precisely like the lotus picture in the book and not at all smudgy. “Nice,” I said. “It’s very black ink, just so you know.” I waited to see if this might concern the nurse.

“I’m going to get a prawn skewer,” she said, eyeing the vendor down the beach. “Want one?”

I shook my head, not trusting shellfish that had been out in the sun all afternoon, and Jesus said, “Thank you, yes.”

We looked at him and a smile raised the flags of his cheeks. My sister laughed and walked away twisting happy feet in the sand, her newly painted black flower swiveling side to side.

I’d looked through the book filled with dragons, skulls, hearts, geckos, swastika-like armband and anklet designs and didn’t see anything I cared for. I didn’t have someone at home who thought tattoos were sexy and didn’t want to further tax Jesus’s thighs.

“I choose for you?” he said and his face turned serious. Then, as if searching for something, his eyes, yes, did run down my legs. Shaving had raised and reddened the pores and my pale legs resembled the skin of a plucked chicken.

“Sure.” I was not at all sure. What was in that ink? I should have asked for an ingredient list. He took the book from my hand and tossed it on the sand.

“Please stay in seat” – he looked around for another chair – “I want to work on your feet.”

“My feet. Okay.” It was still winter back home, so the swastikas would be safely covered when I returned. I watched him pull over a chair, knowing that chair cost the price of a drink. The head waiter, also watching, promptly came over and said something in Spanish, the sounds curling up and over each other. It was a language, I thought, born beside the ocean.

“Cervaca por favor,” answered Jesus and pointed to my bottle of Corona.

The waiter gave me a strained look as if he wanted to tell me something but didn’t have the English. A warning? Did he know this Jesus fellow? Was Jesus just a name he used on female tourists?

“Me, too, gracias,” I said and waved my bottle in the air.

I was embarrassed by the whole tourist invasion thing. Jesus could speak near perfect English and I couldn’t say more than ola, gracias, quanto questa and el bano.

Jesus took a paintbrush from his pack and squeezed out a pool of ink onto a plastic lid palette then sat directly across from me. His short sleeved shirt was missing its first two buttons and revealed the same hairless brown chest of the male dancers we watched the night before on the malacon. A professional group from Mexico City, twenty couples performed traditional folk dances. The men were mesmerizing with their bull fighters’ posture, their macho, muscular movements, feet beating down the floorboards as they led the women with such forceful yanks and throws, and at such speeds, the women wouldn’t have had a second to resist much less think. It was breathtaking.

Jesus inched his chair forward until our knees almost touched. He was my age.

He was thirty-three, tops.

Without asking he lifted my leg and planted my foot on his thigh which caused me to slip down further in my slouchy chair. “I painta top of foot.”

I smiled warily and sipped my beer, tried not to think of my bathing suit, old and too small. I had shaved my legs but that was as far as I’d go.

He hooked his entire arm under my calf to steady my leg and wiped down my foot with a rag drenched in what I trusted was rubbing alcohol judging by its coolness. On the beach in Puerto Vallarta, I imagined telling my friends back home, Jesus washed my feet.

Skipping the paper transfer, he began directly with his ink bottle.

“You’re improvising?” I pictured a cartoon-eyed gecko, a smiley faced sun.

“I like to painta,” he said.

The waiter arrived with our beers. As he set them on the table, Jesus did not look up. I pointed at myself and scribbled on my hand. “Our tab, please.”

When the waiter left, Jesus gave me a shy glance. “Thank you.”

“Thank my sister. I don’t have any money.”

“Then we are not alike. Because none of my sisters have money.”

I laughed and though he was concentrating on my foot, I sensed a smile.

Down the beach waving her half eaten skewer – and was that another beer in her hand? – my sister was bopping up and down alongside a small Mariachi band and its harried sounds of forced cheer.

Staring at the top of Jesus’s head, I wondered if I should make conversation – did you grow up here? Where did you learn your English? What sort of work do you do on the off season? I could tell him I legally grew marijuana for profit, see what he thought of that, considering his country’s drug wars. I said nothing, took off my hat instead – it was past sunburn time – leaned back and let Jesus have his way with my foot. Keeping my eyes closed, I tried to guess what he was drawing… something that started between my first and second toe and fanned out towards my ankle… a lop-sided heart? The waves inhaled and exhaled the distant music, the exclamations of children and broken conversations in Spanish. Jesus blew his cool breath around my toes. Being touched felt ridiculously good and I relaxed in a way I hadn’t since meeting up with my sister in the Phoenix airport.

After an unknowable amount of time, Jesus carefully placed my foot on a towel and then raised my other leg. Would two feet, I wondered, still count as one tattoo? Was it his pride making up for the free beer? He said nothing and I pretended to sleep.

You were sound asleep and snoring.

I was snoring?

I must have drifted off because I woke to my sister’s lightly distrusting voice, “You’re still at it?” before it dropped into genuine surprise, even admiration. “Oh wow. Now that is amazing.” The click of her phone camera and I reluctantly opened my eyes as she apologized to Jesus about the prawn skewer. “I was really going to get you one but he ran out.” She was slurring a little.

I was not slurring.

“Let me buy you a beer to make up for it,” she said and signaled the waiter.

“You already did,” I told her and tried to sit up to look at my foot but Jesus said, “No, don’t move.”

“Well, let’s have another. I’d like one.”

“Not for me,” I said, but she ordered three anyway and talked at Jesus’ bent head as he painted up the inside of my ankle. “My sister lives next to a reserve,” she told him, “Native land, and once a month drives over there and picks up half dozen undernourished dogs and puppies.”

“I know many of the families,” I said so it didn’t sound like kidnapping.

“And they’re happy to let her take them. They can’t feed them, don’t keep track of them and let them roam in packs and breed like… dogs.”

I had told my sister these things with an exaggerated exasperation, knowing it would rouse her sympathies.

“Yet, yet” – her finger shot up – “when she offers to have her vet friend come spay and neuter the dogs, for free I might add, they refuse the offer.” She shakes her head. “It would drive me crazy. Why bring all these unwanted dogs into –”

“But they are wanted,” said Jesus. He blew on my ankle and a shiver sailed up my spine. “If those people not let the dogs do what dogs do, then your sister will not be able to rescue them.”

My sister laughed as if he was being funny but Jesus didn’t smile. And in that instant I saw the reserve situation differently, saw it from above the fray of human interference and labels of right or wrong, as simple cause and effect. The notion that I was some kind of savior to these dogs rang not so much false but unnecessary.

Part paisley, part labyrinthine, part Japanese art, yet not any of those, fanned out from between my first and second toe to cover the tops of my feet, the left design curling asymmetrically up the inside of my ankle like a rogue wave. My first thought was that nothing in my wardrobe would do my painted sandals justice. My second was how much worse my blood poisoning was going to be compared to my sister’s.

“Painted on shoes” – my sister spread her hands as if surprised no one had thought of it before.

“I be back,” said Jesus, his eyes brightening. Leaving his bag and book, he jogged off down the beach, the muscles of his calves being worked by the soft sand.

My sister snorted, a little puff of air. “What’s he doing?”

Though we wanted to head back to our condo to shower and change for dinner, we couldn’t leave Jesus’s pack.

You thought there might be a bomb in it.

I was kidding.

Fifteen minutes later, we startled when he came up behind us.

Jesus, I said, not his name but His name, and I wondered how often his head was turned by swearing tourists. From his sagging shirt pocket he drew out a silver anklet. Little filigree bells hung from the chain and as he lengthened it between his hands, it swung back and forth and the bells made a dull tinkling.

“Lovely,” I said.

“My friend, he makes them.”

“Quanto questa?” I asked because nothing in this country was free. Cheap yes, free no.

He drew a quick breath and gave me a hurt sideways look.

“Sorry” – I felt terrible – “but I assumed you had to –”

“Dinner.” A mischievous smile.

“We’d love to take you to dinner,” my sister said then looked right at me. “Being local, he must know the best places.”

I didn’t know what to say.

“That I do, yes. What time shall I meet you?”

My sister suggested in an hour’s time and he gave us directions to the restaurant of his choosing.

“Why did you invite him for dinner?” I asked once out of earshot. “I was planning on staying in. Packing and finishing my –”

“Come on. It’s our last night. I want to go dancing.”

“I don’t dance.”

“I know. That’s what Jesus is for.”

True, I didn’t dance except around the privacy of my living room with a couple paws in my hands. It was a great way to stop a dog barking. “Aren’t you worried he’s just using us?”

She waved me off. “Relax. Maybe we’re using him?”

My only real sandals wrapped up to the ankle Roman style or had a thick strap across the top of my foot. Both threatened to ruin my tattoos.

“Go barefoot,” said my sister. “You won’t be able to tell.”

“Barefoot, suggests the nurse. On these streets.”

“Not going to wear your anklet?”

“It’s something a thirteen-year-old would wear,” I said, guessing that’s what she was thinking.

“Looks like a dog collar for a Chihuahua.”

I had been going to put it on, thinking Jesus intended it to compliment his tattoo. But the adolescent in me still cared what my sister thought.

On the way to the restaurant, I purchased a pair of black flip flops which blended in, sort of, with my foot art. Jesus was waiting for us on the street outside a dingy looking building whose stucco was cracked and stained. His hair was wet or greasy, I couldn’t tell which, and he wore what looked like a brand new white shirt which lay open at the neck and had the sleeves rolled up. A gigolo’s shirt. His backpack from this afternoon hung from one shoulder and for a minute I wondered if maybe he was homeless.

“You’re not still working?” My sister pointed at his pack as he shrugged good-naturedly.

“I never know.”

We followed Jesus up a single flight of stairs to a dim lit room with a tiled floor, rusty punched tin walls and no more than eight or ten tables. The restaurant was full, not of tourists but Mexicans talking noisily over flickering votive strewn randomly over the table. As the head waiter showed us to our seats, he and Jesus laughed and joked in Spanish. I listened hard, hoping to understand but it was as though I was hearing them from underwater and if I could only reach the surface I’d comprehend the words. As we were shown to our table in the far corner, I could have sworn we were walking ever so slightly uphill. The head waiter gallantly pulled out my sister’s chair for her and Jesus pulled out mine.

Jesus must have told him who was paying.

I don’t think so.

The wooden chair with their thick woven backs were uncomfortably upright and each mango yellow tile on the table’s top was cracked or chipped. There were darkened spots on the red cloth napkins. Grease stains? From a dramatic height, the waiter filled our water glasses before I ordered a bottle of Evian. I’d had my bout of Montezuma’s revenge and that was more than enough.

“It is naïve spelled backwards,” said Jesus.

“What?”

“Evian.” He recommended the margaritas.

“Our margaritas?” echoed the waiter and kissed the fingertips of one hand and my sister ordered a pitcher.

The margaritas turned out to be the perfect blend of sweet and tart and strong. I only hoped the alcohol killed any bugs thriving in the ice. The best guacamole I’d ever tasted was mixed with a pestle at our table in a rough black bowl of volcanic stone – “a molcajete,” Jesus told us – and topped with a deliciously salty cheese, “cojita from Cojita.” The homemade tortillas melted in one’s mouth, the beef for a change was tender, even the refried beans somehow tasted fresh. We exclaimed over the food and Jesus looked genuinely pleased. It was not until half way through the meal did I realize that the room not only had no overhead lights but no roof, and that the dim lighting was moonlight.

“What happens to this place in the rainy season?” I asked.

“It gets very wet,” said Jesus.

My sister laughed too loud.

He pointed back toward the entrance. “The floor, she is tipped a little. And the far wall does not quite reach the floor, you see.”

I pictured rain drumming on the tiled tables and floor, water gushing over the eaves to the street.

“It’s called the washing season,” he added and my sister rolled her eyes.

“Is it true?” I asked.

“Everything is true,” he said. “What else could it be?”

“False,” barked my sister and poured herself another margarita.

After dinner, we went to a crowded disco two stories high, where they played an eccentric mix of the Beegies, Santana and Lady Gaga. I kept watch over our table and a bland and watery pitcher of margaritas safe and while my sister danced with Jesus. During the slow ones, her face rubbed against his white shirt like a rooting infant and I wondered how my brother-in-law would feel about it. And if I was the one with the high stress job and investments portfolios, I’d also need to dance in public, get drunk and rub my head on a stranger’s chest. Jesus’ cheeks bunched every time my sister called something into his curls yet I thought he looked a little bored.

On our walk back to the condo, the alcohol catching up to me, I was drunk enough to believe that the night air off the ocean was the source of the surrealist sculptures that graced the malecon. When you lived in a place where you couldn’t tell where your own skin ended and the air began, ordinary perceptions, I decided, didn’t stand a chance.

I pointed out my favorite sculpture to Jesus; a free standing ladder to the sky, thirty feet tall, with two caped girls made of the same burnt-gold metal, climbing it, one nearly at the top. Their hooded heads were shaped like fat triangular pillows, their capes hanging down their back in severe pleats. A larger version of the girls, the caped, pillow-headed mother, stood down on the ground, her open O of a mouth and extended arms imploring them to come down.

“That is Bustamante,” said Jesus. “It is named In Search of Reason.”

“The mother seems to be saying, don’t go up there,” I ventured, “as if she knows their childhoods are about to be lost.”

“The sculpture,” he said, “makes reason look very dangerous.”

“Ladders are meant to be climbed,” my sister said, steering unsteadily toward a nearby bench. “I can’t walk anymore,” she muttered and laid down on it.

I sat down on it.

“Not far now. I’ll carry you.” He hooked his left arm inside the other strap of his backpack and hiked the bag onto his back. Then he hoisted my sister, too drunk to resist, into his arms.

I felt I should have protested but I could neither carry her nor leave her there so what would have been the point? Besides, like a dog who instinctively trusts certain strangers, I realized I instinctively trusted this one.

“I know a short cut,” he told me and soon I was following him down a narrow alley.

Despite the hour, men, women sat around open doorways, some smoking, others cooking on hibachis, playing guitar or cards, nursing babies or beers. A small pointy eared dog, something larger mixed with Chihuahua weaved around our feet, nose to ground, tail wagging as it hunted. Jesus greeted people and people greeted him back.

“Ola Hayzeus. Como esta?”

I was glad to hear the name was really his. No one in that alley seemed the least bit troubled or impressed by the sight of him carrying a drunk, middle-aged white woman. Was it a regular occurrence? A young Mexican woman pointed at my feet and clucked, then said something to Jesus in a teasing tone.

“What did she say?” I asked when we’d passed.

“That you must have inspired me.”

“Amused you,” I said.

“Amuse, yes,” he said though he may have meant a muse for all I knew.

#

Arriving at the condo, he laid my unconscious sister carefully on the couch.

I was not unconscious.

I arranged her arms and legs and though the air conditioning was off, covered her with a sheet and blanket. As I stood there watching her settle into sleep, Jesus, now standing by the French doors to the balcony, asked if he could paint me.

“We’re leaving tomorrow,” I said, flattered.

At dinner we’d learned that Jesus drove cab in the off season and painted watercolors, his real passion – “of the old buildings and churches” – which he sometimes sold at a gallery in one of the big hotels. So I’d thought he meant paint me on paper. But that wasn’t what he meant.

Then he proceeded to undress you.

He did not.

I went to the bedroom and undressed. For an awkward second I considered putting on my bathing suit then thought of how silly dogs look in doggy raincoats and sweaters. My nakedness felt utterly ordinary as I walked back to the living room. He was outside on the narrow wrought iron balcony, adjusting the placement of a lamp he’d moved outside. As I passed my sister on the couch making sure she was sleeping, I imagined her bolting upright to rip the figurative needle from the record. She didn’t move and when I looked up, Jesus was looking at me with an eagerness akin to hunger. Whether artistic hunger or sexual hunger I didn’t know though both, in that moment, seemed aspects of the same urge, the same need. I continued towards the deck and Jesus stepped back as one steps back to appreciate a painting before he gestured where he wanted me to stand.

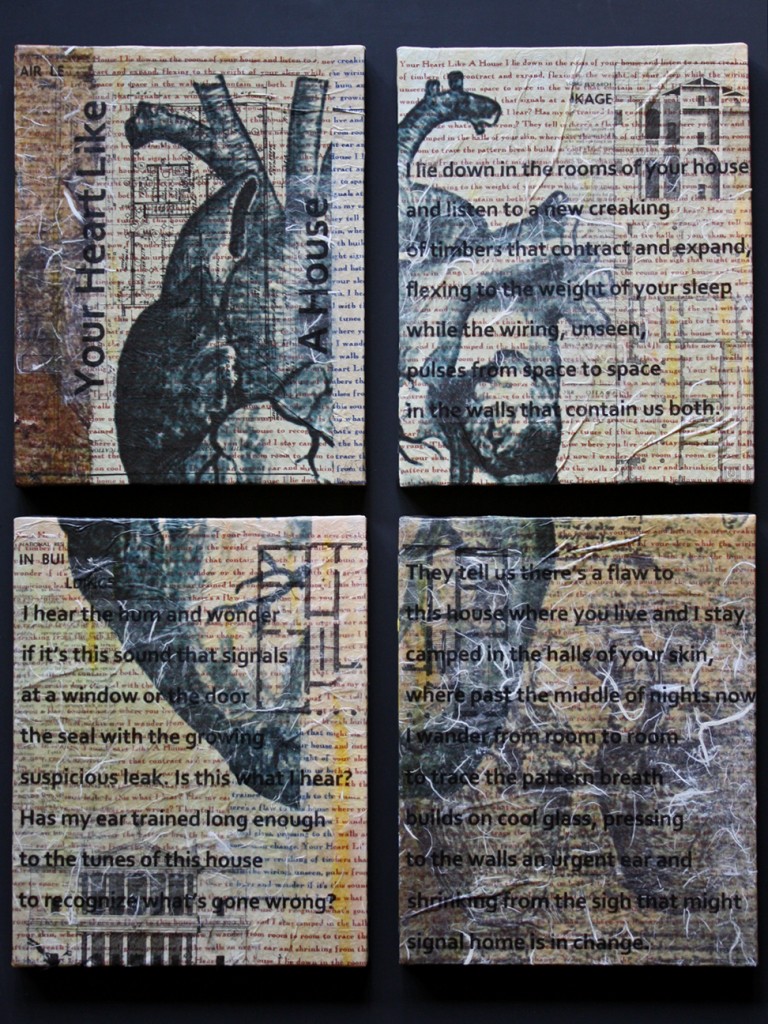

Hidden from neighbors across the way by a jungle of parota trees, the balcony overlooked the bay below and vast sky above, the single blackness lit by a three-quarter moon that much larger than the one back home, its reflection spilling a wavy path along the water.

He took my arm and turned it over. “If the moon were flesh,” he said more to himself than to me.

The single point of his brush was achingly soft where it defined my skin, traveling from elbow to shoulder and down to my breast only to turn and go back again.

He stole the cash from my purse.

No. You bought dinner with cash and left a ridiculously big tip.

We didn’t speak but it was a conversation nonetheless, an exchange of charged molecules, vibrations and wonder. Angled into the light, I arched my back for him, extended an arabesque across his knee, draped my hands shameless behind my head. His depth of concentration stilled my thoughts and made me feel cherished for the simple fact of possessing a body. Only later did I wonder if it was a case of an artist unable to afford his paint and canvases.

He probably drugged our drinks.

The horizon was a pale line of fire by the time his painting reached my inner ankle where it hooked under the wavelike curve of this afternoon’s tattoo. As if all evening he’d been patiently waiting to finish what he’d started. As I turned in a circle, arms in the air, his design spiraled up one side of my body and down the other. He asked me to put on the anklet, then had me keep my face averted as he took several pictures with his phone. Said he planned to transfer me to the canvas some day, that he’d send me a photo of the painting.

“Maybe I’ll buy I,” I said.

“With your sister’s money,” he said and we laughed.

His art and I one and the same, when we kissed he was careful as to where he placed his hands.

He was a con artist.

He was an artist.

Afterwards, energized and unable to sleep, I felt a curious presence in the air as if we were being watched but my sister remained sound asleep on the couch. If there had been eyes in the trees, well, it was too late now.

Jesus left well before the harp sounds of my sister’s ring tone sent her rolling with a groan off the couch. By then I had covered the evidence with long pants and sleeves, a turned up collar, was all packed for the flight home.

I woke to stamping and the tinkle of bells. Saw you dancing on the balcony, hands twisting in the air.

You must have been dreaming.

No, you must have.

—Dede Crane

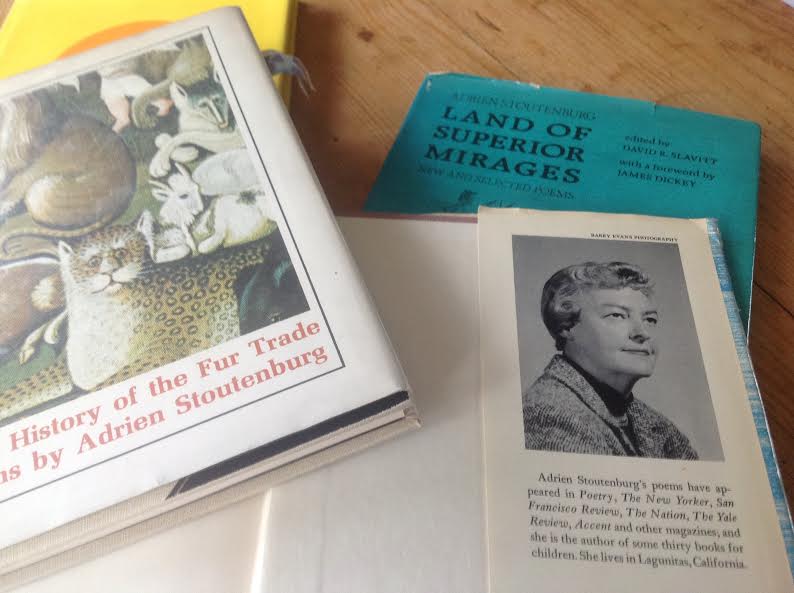

Dede Crane is the author of five books of fiction and co-editor along with Lisa Moore of Great Expectations, a collection of essays on birth. Her work has been shortlisted for the CBC literary prize, a Western Magazine award, the Victoria Butler Book Prize, the Bolen Book Prize and a CLA prize among others. Her most recent book, a novel in stories, is Every Happy Family. She lives in Victoria, B.C. with her husband, writer Bill Gaston, and their children.