All photos by Paul Lindholdt.

All photos by Paul Lindholdt.

His every stride equaled two of mine. His proper province was the clouds. Sage-green moss swayed from pine trees and seemed to wreath his head. Bark chips, fallen needles and twigs beneath our feet made a spongy duff.

As often as our schedules allowed, my father and I packed up gear and threw it in the pickup. We blasted across Snoqualmie Pass from our family acreage in Seattle to camp, fish and hike in the Taneum drainage, Colockum Pass, Crab Creek, Clover Springs. That same canopied pickup served us as our bed.

We needed relief from the population crush in Seattle. We found sanctuary in the arid basin and highlands of Eastern Washington. He and I shared a tacit rapture, an unspoken contract. We favored “the dry side” so far that we came to call those inland pine and fir forests home. My mother and sisters stayed behind.

The coastal interstate can become a kind of asphalt hell for those who love the Big Outdoors. Even out of earshot of the I-5 corridor – that great artery of the West – it brooded over my bent world when I was young, hatching drizzly days and nights. It was as if electromagnetic radiation had found a way to colonize my blood. Traffic racket as lymphoma. Particulates seen and heard and smelt.

Some people always need frontiers. We find them wherever we are able – on fresh continents, on high seas, in outer space. My ancestors hit the Pacific Ocean and I bounced back inland. My design: to reoccupy the intermountain West, reclaim sparsely populated places that others had abandoned for the coast.

My home lies by the Idaho border now. It is low-rainfall natural grassland, like the eastern two-thirds of Washington, mixed shrub-steppe and conifer. Some moisture, mostly snowmelt, distinguishes it from sheer desert. Shrubs struggle to grow on the Columbia Plateau. So do the many tree species in its higher reaches.

From my home, I bicycle an old railway, the Fish Lake Trail. Converted to a community path, it links the towns of Cheney and Spokane. Wild beings throng along it. Attention is a form of devotion, I believe, and so I often slow to ogle them close at hand. The magpies, hawks, eagles, deer; also the smaller sorts that can prove invisible, the praying mantises and walking sticks. On other days I blur by, I opt for speed, music churning in my earphones, leaving the wild beings be.

A freeing sport, this bicycling. It opens riders to aromas both pleasant and rank. Even at speed I can detect leaf mold, pungent forbs, alkali water, a carrion heap. The asphalt that I pedal is a petroleum product. So are the skinny snakes of my tires, my handgrips and cable casings. Such petrochemical reminders subdue any self-congratulation that might otherwise arise from my nonpolluting ride.

Occasionally I load up my bike on a city bus and tote it to the office. After work, I cleat into the pedals for the fifteen-mile ride home. Speeding stealthy as the breeze, I power past milkweed and massive ponderosa pines, past animals sunning or ambling on the path. Flocks of turkeys cause me to wonder which of us would suffer most if we smashed up. Bald eagles above Queen Lucas Lake eye me at eye level from low branches where they fish. Bull snakes, lizards and the occasional rattler soak up the heat radiated by the black asphalt.

In my neck of the woods, moose who stand at shoulders a full six feet high spook us. Several times a year we encounter bulls or cows on breathless trails or backroad scrapes. They tower blackly over our compact cars. They feed on our landscaping and linger in our yards. Approaching them can be hazardous.

Moose kill more people than the leading two or three predators do. They strike with forefeet like horses. We surrender our domestic spaces to them without being told. We lavish them with gratitude for the wildness they exemplify so close at hand. Complete attention extends my utmost devotion to them. One cow I’ve seen twice along my bike route wears a blond chest and a forehead blaze.

From a window in the Spokane home, I’ve watched a young bull nibble at the leaves of a river birch, a top-heavy sapling I planted just the year before. The animal threw its considerable weight into the tree, bent the sapling double and devoured the leaves. Farther and farther up the trunk it pushed and chewed. At last it straddled the whole bole and bent the sapling back to Earth, like Robert Frost’s swinger of birches did for sheer sport in his poem “Birches.”

After the moose finished eating, every leaf was gone. It must have been a rush when the tree sprung back up between its legs. The next year the leaves all sprouted again like revelation, and that river birch grew too sturdy to subdue.

A coyote hunting along the Cheney end of the bike path got a big surprise. Close upon it I pedaled and whistled a shrill alarm between lips and teeth. I was only aiming to keep it alert and alive. It leapt a stream and bolted up the twelve-foot berm. Railway laborers built the berm when they excavated rock to level a path for the railway a century ago. Their heaps of basalt cobbles tower now.

The leavings of the railway laborers remind me they were more than flesh-and-blood machines. A century after Italian immigrants swung sledgehammers and picks to flatten the grade, their rock ovens remain. I stumbled on the ruins of one oven while stalking redhead ducks beside some pothole ponds. Yes, I am a geek who is forever seeking new species to add to his ornithological life list.

Waterfowl forgotten, I focused down on the crumbled dome beneath my feet. Crafted by hand, plastered over by gray lichens, the mud mortar that held the stones in place long washed away, it took a fallen igloo shape. It began at last for me to resemble a human face. A jumble reminding me how people’s mouths cave in and wither with old age. How gums shrink and we grow “long of tooth.”

Using stones of local basalt, the laborers made shift to bake dense loaves of bread. Think wood-fired pizza today. A slate slab toted from site to site served as oven floor. Wood first burnt inside the oven would superheat the entire dome. Then bakers raked out the spent coals and swept clean the slate, sprinkled meal on it, inserted the dough and sealed the door. To bake those loaves from start to finish (I have it on excellent authority) would have taken a mere quarter-hour.

The barely visible aperture of the oven door in my fancy became the tooth-shaken laborer’s mumbling mouth. The structure put me in mind also of a kiva: a subterranean chamber some Indians in the southwest built, its style thought to replicate the emergence of kachinas or ancestors from former environs or lives. For the émigré laborers who made transcontinental rail beds, Europe might have resembled a stained and tainted netherworld, America the promised land.

History lies closer to the surface in this arid landscape than it does on the coastal third of the state. Soils are shallower, scrubbed bare by Ice Age floods. The potholes where I stalk ducks formed when Pleistocene-era vortexes or eddies plucked and scoured bedrock. Those vortexes are called kolks. Bodies rarely may be buried very deep due to all the stone. In the business of Indian-white relations, place names remain as blunt reminders of our ancestors’ legacy of conquest.

Col. George Wright hanged members of the Yakama and Spokane tribes. He slaughtered hundreds of their horses to weaken their ability to survive and fight. As a sort of reward his name memorializes a fort, a cemetery and an arterial drive. In turn the most well-known of his victims, Qualchan, lent his name (however ironically) to a real-estate development, a golf course and a footrace.

Onomastics, the study of proper names, has stirred my imagination since I settled here. The name Spokane looks as if it needs to be enunciated like cane at the end. But it has been given a midrange vowel, and so it sounds like can. The creek where Qualchan was hanged appears on state maps as Latah (Salish for fish), but it appears as Hangman on the national records. Federal cartographers seem unwilling to let the state forget its treacherous bit of regional history.

A tool I found along the Columbia River lay on the surface as well. With my spouse and friends, I was paddling a kayak on the river’s Hanford Reach. We pulled out on an island near the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. Plutonium there helped manufacture the Fat Man bomb the U.S. dropped on Nagasaki in 1945. Since we took that paddle trip, “the site,” as locals call it, has been opened to the public and named the Manhattan Project National Historical Park. Among other topics, it commemorates “The Dawn of the Atomic Age” and “the creation of the atomic bomb, which helped end World War II.” Visitors take busses to the site.

Before we launched our kayaks, I read online: “Radioactive ants, flies and gnats have been found at the Hanford nuclear complex, bringing to mind those Cold-War-era ‘B’ horror movies in which giant mutant insects are the awful price paid for mankind’s entry into the Atomic Age.” If paddling past a nuclear reactor on fast water seems counterintuitive today, we did not think about it at the time.

We had come to experience that last free-flowing stretch of the Columbia River. By the grace of its fast-moving water, Chinook salmon still spawn there. Almost every other portion of the river has been dammed. We stopped to pee on the sandy island formed by sediment before the dams went in. Atop the sand, as if crying aloud be found, a stone tool from the First People lay in plain sight.

In my cultural naïveté, I pocketed the tool. Carried it to my office and put it on a shelf, little knowing that the legal protocol for such artifacts is to let them lie, leave them behind, make the Big Outdoors a big museum. Made of basalt, a fine-grained igneous rock, it was used for knapping, my archeologist-colleague Stan Gough said. To knap is to shape stone by striking at it with another stone to fabricate tools. Stan identified this one as a flensing or skinning implement.

The beauty of that tool resides in its simplicity. In the heft of its antiquity. And for the way it manages to prod the imagination. Its value lies in its lack of utilitarian value. We assign undue value to the useful artifacts – smartphones and microwaves, automobiles and beauty aids – that surround us. The man or woman who knapped the skinning tool focused his or her attention with a keen devotion. A devotion that would have been more Earth-centered than most other forms of reverence flourishing today. Less other-worldly and more this-worldly.

All this useless beauty lies far beneath the surface of the landscape for my kind. Inside our jaded gaze, natural splendor seems to drain away like topsoil in an Ice Age flood. While museums draw millions of observers, and paintings fetch hundreds of millions in investments, the arid landscapes of the American West reside in silence, begging for federal money to rectify decades of neglect. Maybe such landscapes as mine are acquired tastes. Maybe only certain sensibilities find their images mirrored in the stark and Spartan lands of my adoptive home.

My father never was a collector of artifacts, a Wild West reenactor, or a practitioner of creative anachronisms. He was a modern man from Seattle who needed to get away. The last time he visited me, we motored out to open range, that quaint space where grated cattle guards keep stock from roaming. An Angus trotting beside the road tickled him. He joked it was “out for a morning jog.” The cow really looked the part. Tail raised, hoofs clopping, dust puffs settling behind.

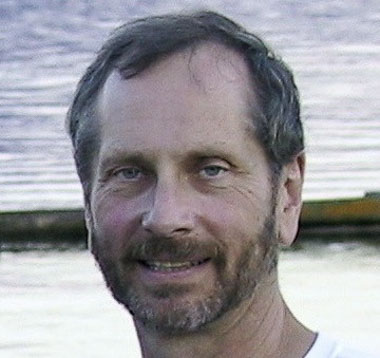

—Paul Lindholt

Paul Lindholdt is a writer and professor of English at Eastern Washington University. He has won awards from the Academy of American Poets, the Society of Professional Journalists, and the Washington Center for the Book. His publications include: John Josselyn, Colonial Traveler: A Critical Edition of Two Voyages to New-England (Univ. Press of New England, 1988); Cascadia Wild: Protecting an International Ecosystem; History and Folklore of the Cowichan Indians; Holding Common Ground: The Individual and Public Lands in the American West; The Canoe and the Saddle: A Critical Edition; and In Earshot of Water: Notes from the Columbia Plateau (University of Iowa, 2011), which won the 2012 Washington State Book Award in Memoir/Biography.

Wellington Street, downtown Chilliwack

Wellington Street, downtown Chilliwack

Cultus Lake, seen from Ryder Lake

Cultus Lake, seen from Ryder Lake

Bromeliads with Red Blossoms

Bromeliads with Red Blossoms Hospital Heart Monitor

Hospital Heart Monitor Green Anole

Green Anole Sunlight on Wall with Euphorbia

Sunlight on Wall with Euphorbia Agave Stalk and Telephone Pole

Agave Stalk and Telephone Pole Why I Live in the Sky

Why I Live in the Sky Bougainvillia

Bougainvillia Gator in Pond

Gator in Pond Hawk

Hawk Raccoon in Humane Trap

Raccoon in Humane Trap Magnolia Blossom

Magnolia Blossom

Mary Donovan

Mary Donovan