Miranda Boulton (The Painter)xxxxxxxxKaddy Benyon (The Poet)

Miranda Boulton (The Painter)xxxxxxxxKaddy Benyon (The Poet)

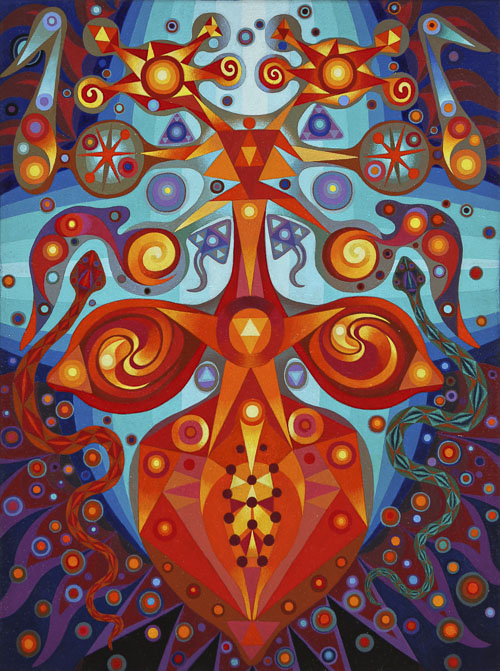

The studio is at the top of the narrow terraced house in what was once an attic. Clean, white lines, and a long slice of window that displays the city below, glittering in the sunshine that has followed a snow flurry. The space has that rich, expectant silence of all places where creativity occurs. It belongs to the painter, Miranda Boulton, and its walls are lined with canvasses that are part of her recent body of work, one of which, Day to Night, was selected for the 2016 Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. The paintings draw on the 17th century Dutch tradition of flower painting, but here the eerie calm of the black background surrounds a vortex of layered expressionistic images that have a mesmeric quality. Miranda tells me how the painting came about:

Day To Night 40 x 30 cm, oil on board (2015)

Day To Night 40 x 30 cm, oil on board (2015)

Miranda Boulton (MB): I was thinking about how I was painting and I was flicking through my phone late at night. I saw this image of flowers and the next day I tried to recreate it. I used to use photos to paint from, I needed something solid to reference. With this painting, I let go of all that and just worked from memory. It was like getting rid of my stabilizers. I let go and it all seemed to come together for me. It became more about the process of painting, of one stroke leading into another, then taking it off and going back and forth in layers of paint… pentimento… it was letting go, so one mark led to the next, it was a process of trying to get to something, of knowing and unknowing.

Pentimento, I discover, when I look it up later, comes from the Italian for repentence, and refers to traces in the work that show the artist has changed her mind in the course of composition. The traces may appear in the underdrawing, or in the painting over the drawing, or in subsequent over-painting. It seems appropriate that working from memory and its infinite layers should result in a palimpsestic painting of such complexity. And appropriate, too, that the unfathomable depths of the internet should provide its origin.

MB: A lot of the source material I use is from the internet. I quite like the distance. When you’re dealing with flower imagery it’s so personal and I find the internet neutralises that. The image becomes a free-floating thing that can mean anything. Then it’s about capturing that meaning.

Victoria Best (VB): I have this idea of the internet as a vast unconscious, just not your unconscious, but other peoples’. It’s like a huge daydream in which you cycle through other people’s discarded images.

MB: I think all the paintings are about ghosts, they are all haunted. For me it’s very much an acknowledgment of the past and the present merging… It’s an interesting thing about painting that you have this whole history behind you and you have to acknowledge that. You have to deny it and accept it; you have to hold it somewhere but it can’t be too much to the forefront. Because I studied art history I had too many images in my head and it took me a long time to desaturate myself. Now I know what my influences are, but I don’t spend a lot of time looking at books because it’s memories I’m interested in filtering. It’s these traces that are left on us that I want to explore and I can only do that when I’m in process. It’s a process of knowing and not knowing and letting go and it’s the actual paint, the texture and the materiality, that allows it out.

VB: It’s all about the flow.

MB: It becomes almost meditative when you know you’re functioning in the moment. You have to hold it all, be aware of it all, but you’ve got to put it over to one side when you’re doing it. I think there’s a process in doing a body of work. You start with an idea and there’s a point where you have to look back and quantify it, think it through. It’s like going below and above water. I understand it now although for a long time I didn’t.

VB: So how long did it take you to do this?

MB: This painting? Probably took me about six months. In different settings and times so there are different layers. Each of these paintings has been completely other paintings before, and worked through over time, and completely destroyed and then worked into again and again. There’s an archaeology.

VB: Do you have to work through sketches in order to get what you want?

MB: No, but I work things out when I’m doing these smaller ones. I work out a gesture, ideas, and then it comes to fruition on the larger ones. They have many more layers underneath the surface. Sometimes it works in one layer, but if you haven’t worked on the layers underneath it doesn’t have quite the same density to the surface.

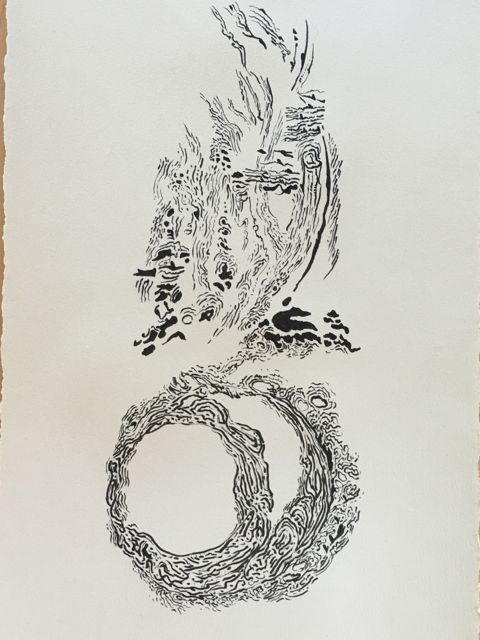

A World in Itself 50 x 40 cm, oil on board (2016)

A World in Itself 50 x 40 cm, oil on board (2016)

Nevertheless, I find myself deeply drawn to the smaller paintings with their bell jar effects. Having been in the presence of Miranda’s work for a while now, the theories of Rollo May on creativity are coming to my mind. In his book, The Courage to Create, May proposed that creativity is first and foremost an encounter, be it with ‘a landscape, an idea, an inner vision, an experiment’. We know in works of art when that encounter has significance for ‘genuine reality is characterized by an intensity of awareness, a heightened consciousness.’ Artists, for May, are people who have the courage to risk turning their intense, sensitive consciousness onto their world in order to have those startling encounters. If you have escapist art, you won’t get that experience of encounter. But with Miranda’s work, I’m conscious of being in the presence of something very real and visceral.

MB: There’s a lot of figuration. This one [Day to Night] there’s a lot of limbs and different parts of the body. To me the image in the middle is like a kind of truncated torso. Whereas these ones I was interested in being much more internal… internal organs, blood and guts. But made quite timeless in a way and contained.

VB: You have this very 19th century effect here with the bell jar. You have something very sterile and held without oxygen but in fact you can see inside it to the blood and the guts. That’s a terrific draw into the painting.

MB: It’s the old and the new, a collision. There’s a timeline when you read a painting. You have a moment when you take the whole thing in, and then you unpick it. Every book, every movie, is fed to you chronologically, but painting is very different. It happens in the moment and then unfolds over time.

VB: Because painting can’t explain anything. Most other artforms explain, but an image doesn’t.

MB: No, you have to bring your own meaning to it, you bring yourself to it and you respond to it in different ways. It can take a lot of time. Once you’ve seen that painting and you start to look into it, you will never see the same thing again. It’s amazing and one thing I absolutely love. It’s the temporal process of painting and I think that’s why building up these layers over time is very important to me, because you’ve got to unpick them over time.

Rollo May also talks about the artistic ‘waiting’, the necessity of holding still and calm in the face of the empty page, the blank canvas, for the next right step to take place. ‘It is necessary,’ he says, ‘that the artist have this sense of timing, that he or she respect these periods of receptivity as part of the mystery of creativity and creation.’ I ask Miranda if this is something she is ever conscious of: waiting for the images to settle and the time to come.

MB: I don’t think I’m aware of it but I’m aware of creating the conditions for it to happen. If you’re too aware you trip yourself up. You have to get in the studio and just do it. This week after the holidays I went back into the studio and I had one day when nothing worked. I was going in and out between the layers of paint looking for the imagery. Two days later I went back in the studio and had a great day. It takes a long time for it to come out of the painting and some days I’ve got a real fight on my hands. But when you get there, it’s so worth it.

VB: When we first discussed doing this interview, I was talking about art often being pre-empted by crisis. And your feeling was slightly different.

MB: I think for me, it’s never been about crisis. It’s a feeling of being very uncomfortable, vulnerable, and then I know I’m getting somewhere because it’s really, really hard.

VB: Rilke says the artist is a perpetual beginner in his or her circumstances.

MB: Yes, you’re going back to the beginning often and questioning. It’s a process of uncovering yourself. Because it really is all about you. Maybe there’s a point when you take a step forward that you know is really positive because its uncovering or exposing something else about yourself. I need that vulnerability to know I’m having a real encounter with the work.

I have been impressed all along by Miranda’s creative serenity. I’m beginning to realise that she has this startling grace because she is so at home in her processes, so welcoming to every stage of creativity, accepting even the hardships – perhaps especially the hardships – as necessary and relevant. I’m intrigued to know how she began painting.

MB: When I first started painting seriously, about 15 years ago, it was landscape based. My Granny passed away at 101. I had a very close relationship with her and when she died I went to the house and found this book of photos that my Grandpa had taken. I never met him; he was a painter and he died before I was born. The photos were taken in Norway in the 1930s and for two years I painted from them. I put other things in, figures and animals and really made them my own. I created this whole mythological world from them. I’ve always had this thing about combining figures within the work whether it’s landscape or still life, there’s just this humanistic side, something fleshy in there. I have tried to move away from it but it always comes back whatever I do. I’ve accepted that now.

Recline 40 x 30 cm, oil on board (2011)

Recline 40 x 30 cm, oil on board (2011)

VB: Did you know you would always do something artistic?

MB: Yes, I always wanted to be a painter. I suppose growing up with painting around me and Granny telling me about her days at the Royal College, it became this mystery, the mystery of the artist.

VB: So both your grandparents were painters?

MB: They both went to the Royal College and met there. Granny went into fashion design and he went into painting. So growing up with it around, it was always a possibility. It was open. It was allowed. And my Grandpa’s studio was still in the house and she didn’t clear it out. So I used to go in there and just stand and look at all the brushes and the paints and the canvasses and things. There was just this kind of romance in my head.

VB: How has motherhood been? Has motherhood got in the way?

MB: I think it’s helped. Beforehand, I used to spend hours thinking, what shall I paint, what shall I paint? And then suddenly, I had no time. I had two hours and I had to get on with it. It really freed me up, it stopped me judging myself. I used to go to a lot more exhibitions and read a lot more books, look at a lot more paintings and suddenly I had no time and it was actually the best thing. I was so image saturated and the possibilities… when you get to a canvas you have endless possibilities. I had to strip it bare; it was a kind of going inwards to go outwards. And also, because I was in the home, it kept me sane. So my son would go to sleep and I would put the baby monitor on him and go and paint.

VB: Did the landscapes move into the flowers? Did you have a stage in between?

MB: Yes there was a stage when I was playing different genres. I like working within a genre, a seam I’m really mining. So I did the landscapes and then I was working with lots of different imagery for a couple of years. I used to trip myself up. I’d get so far with a line of imagery and then think, that’s getting a bit problematic, I’ll try something else. But you never get into anything in depth if you don’t stick with it.

VB: You need that concentration and focus.

MB: If you look up here I’ve got rules of painting. I did those nearly two years ago when I said to myself: you’ve got to hone in. And I’ve stuck to it and it’s been the best thing.

VB: How much is art about permission?

MB: Yes, precisely. But you’ve got to understand your own methods of making it harder for yourself – or momentarily easier, but harder in the long run. I was making it easier by saying, I’ve got bored of this, I’ll do a figure, I’ll do a landscape, I’ll do all of it. But actually I was tripping myself up for the long term. In the short term it was keeping the flow going.

VB: Isn’t that the way? The running away is never…

MB: The facing up to it is what matters. You stick with it. I told myself: if you want to paint flowers, then you paint flowers. Do what you want.

VB: Why is that the hardest thing? To say: do what you need to do, what you want to do, what exactly speaks to you in the moment, free from other people’s demands and expectations. I don’t know why that’s so hard.

MB: We’re very self-critical. But I think the thing that’s probably changed over the last few years is painting from memory. Although the landscapes were about memories they weren’t my memories, they were my grandparents. It’s about traces left on our minds. It’s an interesting thing about the process. You think you’ve gone somewhere really different and then you realise…ah, I’m back in the same place. But maybe I have moved forward a little bit. For you, it’s really different, but probably no one else realises it.

VB: So maybe it was with the flower paintings when you felt you’d actually found your…

MB: Yes, I understood because it was the second massive body of work I’d done, and I understood what the first one was about through the second one on a much deeper level. You have to have a fascination with something. Then to understand that fascination you have to do it for long enough so that you can go back to the beginning many times.

VB: You have to have a whole revolution.

MB: You have to lose your way massively and then find it again.

VB: The art of going wrong.You have to go wrong first before you can go right.

MB: And this is what I’m talking about with the vulnerability. You have to sit with that absolute discomfort.

We have stumbled into the territory of my favourite theory about creativity – that it is as Kathryn Schulz says in her book Being Wrong, ‘an invitation to enjoy ourselves in the land of wrongness.’ She argues that art comes about because ‘we cannot grasp things directly as they are.’ In consequence, there exists an exploitable gap between the real and our perceptions, a gap embroidered and embellished by the powers of imagination. The artist who permits free rein to imagination effects entry into a parallel world ‘where error is not about fear and shame, but about disruption, reinvention and pleasure.’ This extends to the consumers of art as well, for we look at art in order to lose ourselves, so that we might find ourselves in new ways. I think of Miranda’s pentimento, the layers and layers of overpainting that create these deep, pleasurable palimpsests in which we cannot distinguish which lines, which forms are the ‘right’ ones to read. And I think of her embrace of vulnerability and discomfort, knowing that these are the states that open into creativity, not block it. It seems strange to think about wrongness in relation to Miranda and her art, when she is so clear in her vision, so steady in her process, and so calm about the necessity of creative disquiet. But it’s the eerie uncertainty of her paintings and their ghostly resonance in which the past and the present collide that remain in my memory long after seeing them.

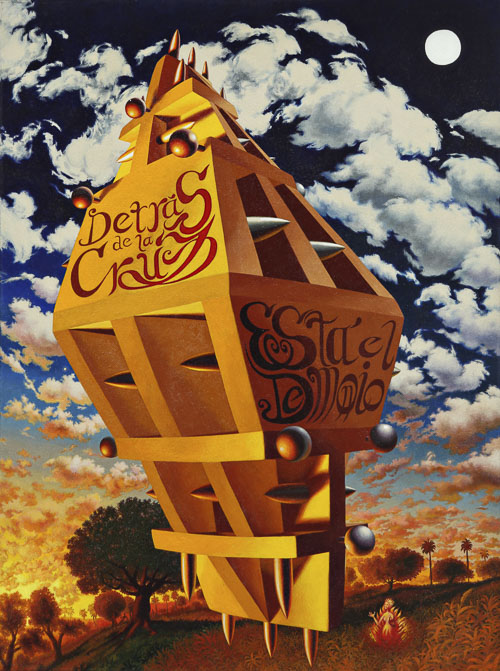

Mary 60 x 65 cm, oil on board (2017)

Mary 60 x 65 cm, oil on board (2017)

MB: I’ve just done these two paintings this week. I don’t think this one’s finished, though this one definitely is. It’s possibly a little bit more easily read than a lot of my paintings but I’m so happy with it. It’s just hit something for me.

VB: I love the cameo. It’s something my eye is drawn to the whole time. I’m looking at the centre always in reference to the frame.

MB: For me it’s like a mirror. You’re reflecting yourself within the imagery.

VB: It’s interesting what you were saying about having to work in a place of knowing and not knowing, of certainty and doubt, the past and the present. There’s a really interesting play here between wildness and control.

MB: Yes, there’s a sort of romantic quality to it. There’s a deliberate wornness, an acknowledging of age. Which is reflected in the background and also in the imagery.

VB: I love the texture of the pink. It feels like it’s reaching out to me.

***

The room is small but high-ceilinged and orderly, comforting and snug. There’s one wall of bookshelves filled with thin volumes of poetry and notebooks that have the properly thumbed and used appearance of books constantly considered and reread. Above the small, neat, desk there is the most beautiful storyboard I have ever seen. I can’t read the lines printed on the white cards that fill the margins, or make out very clearly the cluster of images pinned in the centre, but it feels as if something very rich and complex is going on in this thought cloud. The room belongs to the poet, Kaddy Benyon, whose first collection, Milk Fever (2012) garnered awards. She is working on her second, Call Her Alaska, inspired by Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale, ‘The Snow Queen’, and has finished a third, The Glass Harvest. She is also currently writing a novel. Kaddy’s early career was as a television scriptwriter, but then her work took an abrupt turn.

Kaddy Benyon (KB): I think it was when my son was a baby that we moved to Cambridge and I did the MA at Anglia Ruskin in Creative Writing. I thought: I am only going to write teen novels because I’ve written Hollyoaks and I know exactly what I’m doing, thank you very much. And I came out of the machine two years later a poet. I wasn’t expecting that; I didn’t really know how that happened.

VB: Did you get an assignment to write poetry that started you off?

KB: In my final year there was going to be a scriptwriting module and I said to my tutor, with respect I’ve done this as a job and I think it’s a bit of a waste of time. Can I do an independent study? And they said, yes, we have this brilliant poet [Michael Bayley] who tutors people. Would you be interested in poetry? I was really playing hard to get and said, well I love reading it but I don’t think I’m a poet. And my tutor said, just go for a week with him, see what you think. It’s seven years this week that I met him and we’ve still got this lovely collaborative relationship. The first poem I ever wrote for him, we met up for the tutorial afterwards and he was very serious. He looked at me and I thought, fuck, it must have been awful. And he said, this is seriously good, send this out. It got taken by London Magazine, the first thing I ever wrote and it’s in my book [Milk Fever] as well, the one called ‘Ice Fishing’. He really loved it and he just encouraged me. He reads every poem that I produce, even now.

VB: It’s funny isn’t it… do women have muses? Is he a muse?

KB: I wouldn’t say he is. He’s sort of like my safety net. If a poem hasn’t been Michaeled I feel it’s no good. It needs to go through him and get the thumbs up or the thumbs down. Sometimes he’ll say, this isn’t quite there, just leave it for a few months, come at it from this angle, or this drafting technique. Everyone needs someone who’s above them on the ladder and who says, come up here, it’s great. I don’t really know any other writers who haven’t got that first reader, who you can stand in front of, kind of naked, and say: I’ve produced this, I don’t know what it is. Could you look at it? Do you still love me? I’m nervous, Michael’s nearly retired now and he wants to do less and less. So I feel like I need to have my eye out. I need to have a writing mummy or daddy, because it can’t always be him, even though it’s been brilliant and I hope it continues as long as it can. It’s frightening. I suppose to acknowledge the need for that is halfway to getting it.

VB: So let me get this straight. After Milk Fever, you did the ‘Snow Queen’ poems [Call Her Alaska] and then you moved onto this new body of work?

KB: The Snow Queen isn’t finished. That was why I was in residency at the Scott Polar Museum [in Cambridge] and that was Arts Council funded. It did produce the exhibition, ‘The Snow Queen Retold’, and there are something like 200 poems in draft. About 30 are done.

Robbergirls

You came and I was longing for you.

You cooled a heart that burned with desire.

…………………………………………………….—Sappho

The Robber Maiden

You were the prettiest little trinket

these sooted eyes had ever seen,

& yet I robbed you

of your defences: laid you

out on a bed of straw, slipped

you dripping from your hood, your furs,

those rabbitskin boots.

You wept when I licked the icedust

glister from your breasts; kissed

your twenty-three ribs; spread

heat & delight between your thighs.

We wintered on whispers &

firelight & my hundred smoky

turtledoves peeping from the rafters

seemed like poets, rolling love

on their tongues instead of ashes.

Gerda

Slipping from her mother’s whiskered

skins, she haunts my tangled forest

dreams, a bandit in snicking

thickets. She creeps under cover

of leafmould, fingerblades grazing

my lips, strips me of my mantle, my kirtle,

those rabbitskin boots.

Pinned between her jack-knifed limbs,

a scent of flame & fury rises from her

skin; her flapping rabble of filthy

mocking birds laughing from the rafters.

Snowmelt: whetted backbone to

aching backbone, I steal from her

choking stranglehold, drag her kicking

heart from its unlocked, bare chest,

spit on the embers of her desire & flee.

VB: How many poems are you looking to have?

KB: Probably 50 to 60 so I’m way over. I’ve got the luxury of choosing. But I had a bit of a blip. It was in 2014 in the spring, just a bit of a mental blip and needed to take time out. I couldn’t write anything for three to six months but I was still at the Museum, and it was quite difficult because I was almost pretending everything was fine. But I wasn’t producing, although I was doing all of the research. I was loosely following the journey that Gerda makes in the fairy tale but sometimes I put quite a feminist slant on it, sometimes quite a Sapphic slant with her and the Robber Girl. I did my research trip to Finland and it was almost like I was taking in so much information and possibilities that I couldn’t hone it down. All of my notebooks are just full. About a year ago I went through them and typed up everything I could, so it is a more manageable beast now.

VB: What was the first thing that drew you towards ‘The Snow Queen’?

KB: When I was seven, my dad went to Denmark on a business trip and he bought me a version of the book back. I just fell in love with the pictures, the one of the Robber Girl in particular. Because they terrified me but they excited me at the same time. So there was quite a wicked pleasure to it.

VB: There is something about the Snow Queen. What is it about her?

KB: I assume, with my Jungian head on, that she is an archetype in all of us, scares all of us, and we think she’s going to kiss us and we’ll freeze. I don’t know.

VB: I think she’s somewhere between being scary and comforting. She’s the cold mother. There’s the possibility of the maternal and of patronage… but there’s also something vicious as well. This is what interests me about poetry. I can get my head around a novel of the ‘Snow Queen’ or an analysis of it. But poetry — it seems to me a strange way of saying that what you want to say isn’t easily said.

KB: I feel a real chiming with the fairy tale and I think I’m all the characters in it as well, like in a dream. I can be icy and distant when I’m into my work, and I could attach my sledge to an idea and go racing off without thinking.

VB: So you were working on Call Her Alaska, and then the poems on the islands came along?

KB: Yes, I had this breakdown I mentioned in 2014 and I was feeling so ill and I said to my husband, let’s just go somewhere we’ve never been before, let’s go to an island in the middle of the sea. My poetry tutor used to mention this place that was a bit like Avalon; I didn’t know whether it was fact or fiction, and it was Lindisfarne. I said, let’s go to Lindisfarne and all four of us just fell in love with it and we’ve been back every year since. I think about 30 of the poems came just in that week. Then I got a residency this time last year to Eigg, and we went to Skye in the summer. So the collection is about those three different islands, and I don’t know why they came to get me, but they did. That manuscript is being Michaeled at the moment. And I’m just scared of that as well. I’m scared of everything I write.

Cloudberries

……..(after Edwin Morgan)

There were never cloudberries

like the ones we found

that tender afternoon

in peaty ruins

Lindisfarne Castle

a late autumn sunlight

wind moving in the dunes

heather staining the mainland

your pale hands emerging

from fingerless gloves

to uncover a little plant

preserved in salty darkness

you untucked its leaves

revealing three amber jewels

the first bruised to a juice

the second placed delicately

on your tongue your blue eyes

on mine my open mouth

watering to take the final honey

cluster between my lips

leaning side by side

our wellies kicked off

you urged me to abandon

my island living

walk the causeway beside you

my tight fist nestled in your palm

let me be beautiful

in that remembered light

precious as the rose gold lodes

coursing deep within

your highland hills

let me reach for you and follow

let the tide rinse away our tracks

VB: The anxiety of creation is so prevalent. I remember reading that creativity is a form of trespassing on the divine – Prometheus being one of the first examples, stealing the secret of making fire, and the Gods punished him for that.

KB: The liver business. That feels right, intuitively. This novel I’m writing… it’s fast. I feel like I’m channelling it, or I’m being whispered it, so it’s not really mine. It’s almost like the gods are giving me this gift and then I will claim it as my own by saying: by Kaddy Benyon. But it doesn’t really feel like that.

I tell Kaddy about one of my favourite theories of creativity by the psychotherapist, Christopher Bollas in his book Cracking Up. Bollas pointed to the constant free flow of ideas, images and thoughts that race through the mind mostly unobserved as the basic element of our fundamental creativity. Like rush hour traffic, these mental elements congregate around experiences that have a particularly intense emotional resonance, though often they may be simple things, scarcely worth the charge they give us on first appearances. Bollas talks about ‘psychic bangs, which create small but complex universes of thought.’ But I wonder whether the sensitive, dynamic, creative mind both uses this free flow and falls foul of it. I think that stress plus a freewheeling mind often results in catastrophising. Creative folk may well produce beautiful and innovative result from free association. But it’s hard to prevent our thoughts from delivering us into dark mental alleyways where we’ll likely get beaten up.

KB: That really makes sense to me because my analysis has underpinned everything that I’ve written that I’m proud of. The analysis has taught me to use my mind in a free associating way that I use with all my poems. It’s almost like a mind map.

VB: It’s about processing, isn’t it? Because things get processed very small in the creative mind.

KB: That’s true about noticing, I think, letting your mind be open to noticing how things are connecting up that you might not be conscious of yet. That’s what the analysis has done for me.

VB: You went into analysis after the breakdown?

KB: No, I was already in analysis. It was 2008, so it’s been nine years this January and my first creative writing teacher at university, Edmund Cusick, had died quite suddenly and quite young and I had just had my son. We’d moved house as well. I was overwhelmed and I needed someone to talk to. I didn’t actually know what analysis was at that time, but I knew that my teacher who died, who was a poet as well, was very into Jung. So I looked it up on the strength of his stuff. He was the first person, when I was 18, to tell me I could write. He was the first one to give me permission. I was at university and he used to say, right, I want you all to keep a dream diary and write poems in response to your dreams. So that’s completely how I work now.

VB: So dreaming is an important part of what you do?

KB: I’ve had poems that have arrived from dreams, fully formed. Not often; a couple in Milk Fever, like the one about Louise Bourgeois just came. I do keep a dream diary, because I think dream material is free from all the stuff you’re trying to force or impose upon it to make it mean something. And it means something in its own way anyway, it just might not make much sense. I quite like things that don’t make sense. They have an intuitive sense but not a logical one and I like that.

I’d been reading Carl Phillips’s wonderful meditation on poetic creativity, The Art of Daring, shortly before seeing Kaddy, and his insight on poetic meaning, that any ‘successful poem – one that is true to human experience – will resist closure. To be resonant is to resist absolute closure’ occurs to me now, thinking about the experience of dreaming. Closure, or what stands in its place in the poetic universe, often comes in the form of form, in the typographical shape of the poem on the page. Phillips suggests ‘Form, shape – these may be our only way, finally, of making sense of the world around us. And the body may be the one form, finally, from which we begin, each time, our knowing.’ I’m intrigued by the neat, firm formality of Kaddy’s poems, and one, ‘Causeway’, is a particular favourite of mine.

Causeway

No workmen or bulldozers, just two plucky women ceaselesslyX trying to reach one another despite winter storms, rising tides, savage winds untamed from Scandinavia. Daily they strive – not so much to hold back the tide – but to work with it, around it, in deference to its unstable surge to spoil, spill and gush across their toil; to ransack any progress and demolish vague relations to the mainland. Natural drainage is compromised by drifts of sea-born debris: silt, salt, wrack and shattered shells, all plotting to induce some fresh destruction. And I know, god how I know, how it begins to feel like a punishment, a kind of ritual destruction, this endless, joyless, repeating and repeating and repeating only to witness the sea’s deleting.

KB: It’s about the analytical work and the way my emotional tides come along and destroy it every now and then. And we start again. I’m trying to do new things with form and every experiment I don’t know if it works or not. In Call Her Alaska there are a lot of two-sided or two-faced poems that are almost wings with a column of nothing in the middle. One is about Gerda on one side and the Robber Girl on the other and they’re seeing that they shared a bed in a very different way. It was quite complicated to do and sometimes I just want to rip them up and throw them out the window. But when they come good it’s worth it.

VB: I always think of you as so finished in what you do. Whatever I’ve read of yours has been so polished, so beautiful. I think of you as someone who produces these carefully faceted gems.

KB: I’m aware that I’m doing that as part of my process. My eye can’t tolerate a messy poem. But I think it’s too much of a constraint on myself to express myself neatly and symmetrically at all times. Because life is messy and humans are messy.

VB: But maybe there’s something in that form that holds back, that holds you back in a sense.

KB: I think I needed that with Milk Fever for sure. I needed a container to be absolutely watertight because I wasn’t sure what I was dealing with and it was rising up from somewhere I’d never tapped. And I was constantly flooded with the material that was coming. It was almost like I had to impose the form on it. But now I’m more comfortable with my process and I feel I can’t be writing poems that could have been in Milk Fever now. I have to have moved on and be taking risks even though its terrifying.

VB: Thinking about containers and Milk Fever… I was just thinking about your mother and the fact that the hug is the basic form of containment. It’s that: I’ve got you moment. You’re within the circle of my arms.

KB: Yes, and it’s probably also the strongest recurring theme in my analysis. I’ve said to my analyst nearly every day for nine years, can I have a cuddle? And she’ll say no, you can’t have a literal cuddle, but I’ll cuddle you by holding you in my mind. But I do feel the analysis has opened up the creativity. I was aware since I was six I wanted to be signing books in Heffers. That’s all I wanted, ever. But I didn’t know how to do it, or how much of my self I had to draw up and present to the universe to see if the universe would like it or not.

VB: One of the things I’m most interested in is this idea that art comes from the place of being wrong. And that can be from the fact that reality is always distorted by our perceptions. I’m thinking of what Carl Phillips says, that poems tend to transform rather than translate.

KB: What comes to mind when you say that is: when I was writing a poem called ‘Strange Fruit’ it came from my most shameful feelings when I was a teenager, ugly and repulsive, and I felt like I had to say it, but I had to put it into beauty. Is that what you mean? That I made something ugly beautiful?

Strange Fruit

Sometimes I have an urge to slip

my hands inside the soiled, wilting

necks of your gardening gloves;

to let my fingers fill each dusty

burrow, then close my eyes and feel

a blush of nurture upon my skin.

Sometimes I am so afraid my hurt

will hack at your figs, strawberries,

or full-bellied beans, I dig my fists

in my pockets and nip myself. Sometimes

I imagine the man who belongs to

the hat hanging on the bright-angled

nail in your shed. I think about you

toiling and sweating with him;

coaxing growth from warm earth;

pushing life into furrows. I am curious

about what cultivates and blooms

there in your enclosed, raised bed –

yet I want no tithe of it for myself.

Sometimes I just want to show

you the places I’m mottled, rotten

and bruised; I want you to lean close

enough to hold the strange fruit

of me and tell me I may yet thrive.

VB: Yes, but without translating it into something obvious or too straightforwardly explanatory. You didn’t need to have an explanation. What you needed to do was transform that sense into something meaningful.

KB: That makes sense. And I think I didn’t really realise the weight of that in my work. Not just in my poetry, but in the novel as well. It’s almost like the kernel of it is my biggest shame. Or rather, the thing I was made to be most ashamed of, but I actually found it beautiful.

VB: I like that.

KB: I was reading one of the Notting Hill Editions books of essays, the one called Humiliation. The author was saying something about shame and vomiting and diarrhoea when all your most smelly, shameful, awful innards just come out violently, and that’s like the creative process for me. That’s how it feels. And I do feel mostly ashamed of my productions until I can polish them and make them beautiful. My first drafts are like the worst nappy in the world, just a shit explosion.

VB: Shame is a cul-de-sac of emotions. Guilt is about reparation, but shame you’re stuck with. I’m ashamed of myself, I can’t exist, I can’t live, I can’t be. You have to do something with that. The psychiatrist, James Gilligan, made a study of the most violent prisoners in jail and found that they had all suffered terrible shame in early life.

KB: It’s a real head-hanging one, isn’t it? Shame and rage are next door neighbours.

VB: And rage turned inwards is anxiety. So there’s a whole circle of stuff going on… it’s the circle of artistic life, isn’t it?

KB: Why do we do it?

VB: Because ultimately it’s reparative. Somewhere along the line.

I, too, have that Notting Hill Editions essay by Wayne Koestenbaum entitled ‘Humiliation.’ Later, rereading it again, I find an anecdote that strikes a chord, as it were. One of his fellow students at an unnamed summer music school tells him about the way that a popular teacher whose speciality was ‘relaxation’, ruined her own performing career by sitting down at the piano for her onstage debut before an applauding audience only to be sick over the keyboard. Koestenbaum has this reflection to make on the story: ‘Vomit on the keyboard – that image symbolises, for me, the always possible danger of the body speaking up for its own rights, against the stringent demands of the mind’s wish to construct a plausible, attractive, laudable self for other people to consume.’ Thinking about Kaddy’s poetry and the anxieties that surround her creative process I feel a strong belief that it’s one of art’s most important tasks to stand up for not just the rights of the body, but the reality of the body, the reality of our messy, upsetting, often overwhelming existence. It’s the job of art to talk about all the truths no one wants to hear, in ways in which they might finally manage to hear them and be assuaged. In that way Kaddy, like other artists, can experience the all-important acceptance of what feels like the worst of the self, though it’s only our shared humanity. But what I also hear in everything Kaddy says is her intense, passionate love of her creative process. In the very act of polishing that turd, Kaddy’s love trumps her fear and that is a powerful act. I ask her if she feels valid as a writer.

KB: When Milk Fever first came out, it was like, oh I’ve produced something and people like it and this is strange and nice. That was 2012 and I do feel very under pressure to produce either another collection or do something different so I can sustain that viability. I don’t feel like it’s just a given forever. I find myself longing to be in the position, either as a poet or a novelist, where I have a publisher and any idea I have will be considered, and hopefully published. They have faith in me, I have faith in me… but I just don’t feel I’m there yet.

VB: It sounds like a good family thing. You want that parental authority in place.

KB: I’m never not working. It’s constantly what I’m doing and worrying away at. I love it. But when you can’t prove it… People often ask me in the playground, ‘When is your next book coming out?’ and it’s the worst question ever. Because the answer is not only when I’m ready, but if I ever get another publisher. I think it was quite affecting that Salt stopped publishing single author collections of poetry about the year after mine came out. So I went from the euphoria of yes, I’ve arrived! To oh shit, I’ve got to start again. So now with The Glass Harvest, it’s kind of done. I imagine if I sent it off to a few places they’d at least read it because I’ve been published before. But there’s no guarantee and I just can’t face the no. It took me two years to write that and it just meant so much to me as it was all that I went through. So I’m not sending it anywhere. Because that might just stop me writing altogether and I’m in the middle of this novel.

VB: The process is horrible and can be toxic at times, and not at all good for people who are writers. It’s ironic that you couldn’t have made it worse for people who are writers.

KB: And it’s frightening, weirdly, conversely, just to know that an agent is waiting to have a look [at the novel]. Even though most of the other writers on Hollyoaks had agents, I’d got the job on my own and I didn’t need an agent to look for anything else. And now it’s that horrible thought: would anyone be interested? Would anyone take me on? Would they earn any money from me? Oh God, too much pressure. You know when you don’t know whether you’re being bold or stupid? That’s where I am with it.

VB: My money’s on bold.

***

This is what happens when you work with creative people. Miranda and Kaddy – who happen to live minutes apart – became interested in each other’s work over the course of these interviews. Now Kaddy has one of Miranda’s paintings on her wall, and Miranda has some of Kaddy’s poems. They both intend to create something in response to the work of the other. In six months’ time, we’re all going to meet up again to see what they have produced and to discuss the creative processes they went through. Intense, irresistible curiosity, the lure of the new idea or the intriguing object, was something we never spoke about in our interviews – it just went ahead and happened instead.

.

Born in Cambridge, Miranda Boulton has a BA (hons) in Art History from Sheffield Hallam University and finished three years on the Turps Banana Correspondence Course in 2015. She has exhibited widely across the UK and was selected for the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition (2016), The Salon Art Prize (2011) and The Artworks Open (2010 and 2011). Her exhibitions include: a two-person exhibition ‘Off Line On Line’ at Studio 1.1, London (2015), and the solo exhibitions ‘Lost in The Middle’, New Hall Art Collection, Cambridge (2012) and ‘Outside In’, Madame Lillies Gallery, London (2011). She has work in private collections in France, USA, Ireland and many locations within the UK. Miranda is currently co-curating a group exhibition ‘Storyboard’ at Lubomirov Angus Hughes in London, which opens on the 14th April. www.mirandaboulton.co.uk

Kaddy Benyon’s first collection, Milk Fever, won the Crashaw Prize and was published by Salt in 2012. She has also written poems in response to Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘The Snow Queen’ for a collaborative exhibition with a costume designer during a residency at the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge. Last year Kaddy travelled to the remote Scottish island of Eigg for a residency with The Bothy Project. Whilst there she wrote poems toward her second collection, The Glass Harvest. Kaddy is a Granta New Poet and has been highly commended in the Forward Prizes.

.

Victoria Best taught at St John’s College, Cambridge for 13 years. Her books include: Critical Subjectivities; Identity and Narrative in the work of Colette and Marguerite Duras (2000), An Introduction to Twentieth Century French Literature (2002) and, with Martin Crowley, The New Pornographies; Explicit Sex in Recent French Fiction and Film (2007). A freelance writer since 2012, she has published essays in Cerise Press and Open Letters Monthly and is currently writing a book on crisis and creativity. She is also co-editor of the quarterly review magazine Shiny New Books. http://shinynewbooks.co.uk

.

.

Josh Dorman in his NYC studio

Josh Dorman in his NYC studio Camel Cliffs – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, 12 x 14 inches, 2009

Camel Cliffs – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, 12 x 14 inches, 2009 Knight Errant – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel,

Knight Errant – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, Tower of Babel (for Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman) – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, 48 x 38 inches, 2016

Tower of Babel (for Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman) – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, 48 x 38 inches, 2016 Night Apparitions – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel,

Night Apparitions – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, Welcome to the Machine II – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, with resin, 12 x 12 inches, 2017

Welcome to the Machine II – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, with resin, 12 x 12 inches, 2017 Wheels – graphite with antique collage elements, 10 x 20 inches, 2017

Wheels – graphite with antique collage elements, 10 x 20 inches, 2017 Thelma, Memory Bridge portrait – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, 34 x 42 inches, 2006

Thelma, Memory Bridge portrait – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, 34 x 42 inches, 2006

April – ink on synthetic paper, 44×60 inches, 2008

April – ink on synthetic paper, 44×60 inches, 2008 M4 – acrylic on PVC, 48×48 inches, 2013

M4 – acrylic on PVC, 48×48 inches, 2013 M5 – acrylic on PVC, 48×48 inches, 2013

M5 – acrylic on PVC, 48×48 inches, 2013 M6 – acrylic on PVC, 48×48 inches, 2013

M6 – acrylic on PVC, 48×48 inches, 2013 May – ink on synthetic paper, 44×60 inches, 2008

May – ink on synthetic paper, 44×60 inches, 2008 October – ink on synthetic paper, 44×60 inches, 2008

October – ink on synthetic paper, 44×60 inches, 2008

John Hampshire, photo by Elana Gehan

John Hampshire, photo by Elana Gehan Self-portrait, acrylic on panel, 11″ x 14″, 2013

Self-portrait, acrylic on panel, 11″ x 14″, 2013 Gina, acrylic on panel, 11″ x 14″, 2014

Gina, acrylic on panel, 11″ x 14″, 2014 Lauren, acrylic on panel, 11″ x 14″, 2015

Lauren, acrylic on panel, 11″ x 14″, 2015 Inherent Strings attached, acrylic, string on panel, 11″ x 14″, 2015

Inherent Strings attached, acrylic, string on panel, 11″ x 14″, 2015 Labyrinth 308, ink on door, 32″ x 80″, 2014

Labyrinth 308, ink on door, 32″ x 80″, 2014 Labyrinth 338, ink on door, 24″ x 80″, 2015

Labyrinth 338, ink on door, 24″ x 80″, 2015 Labyrinth 311, ink on door, 32″ x 80″, 2015

Labyrinth 311, ink on door, 32″ x 80″, 2015 Zombie – watercolor on paper, 24″ x 18″, 2015

Zombie – watercolor on paper, 24″ x 18″, 2015 Dowser – watercolor on paper, 24″ x 18″, 2015

Dowser – watercolor on paper, 24″ x 18″, 2015 For Fortuny – watercolor on paper, 24″ x 18″, 2015

For Fortuny – watercolor on paper, 24″ x 18″, 2015 La De Da – watercolor on paper, 50″x 40″, 2016

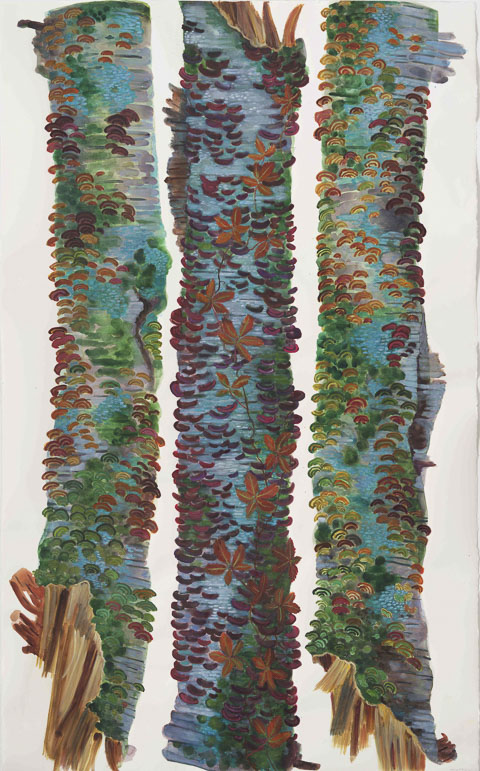

La De Da – watercolor on paper, 50″x 40″, 2016 White Birch – watercolor on paper, 24″ x 18″, 2015

White Birch – watercolor on paper, 24″ x 18″, 2015 Menage A Trois – watercolor on paper, 7′ x 4′, 2016

Menage A Trois – watercolor on paper, 7′ x 4′, 2016 Showtime – watercolor on paper, 7′ x 3 1/2′, 2017

Showtime – watercolor on paper, 7′ x 3 1/2′, 2017 Showtime II – watercolor on paper, 5′ x 3 1/2′ , 2017

Showtime II – watercolor on paper, 5′ x 3 1/2′ , 2017

Miranda Boulton (The Painter)

Miranda Boulton (The Painter)

Evelyne Porret and Michel Pastore

Evelyne Porret and Michel Pastore Rikki Ducornet

Rikki Ducornet Aperture 14, 16″ x 16″

Aperture 14, 16″ x 16″

Aperture 12, 16″ x 16″

Aperture 12, 16″ x 16″ Partners 1, 17″ x 23″

Partners 1, 17″ x 23″ Partners 2, 17″ x 23″

Partners 2, 17″ x 23″ Partners 3, 17″ x 23″

Partners 3, 17″ x 23″ Partners 4, 17″ x 23″

Partners 4, 17″ x 23″ Triptych, overall 16″ x 40″ framed (individual images 10″ x 10″)

Triptych, overall 16″ x 40″ framed (individual images 10″ x 10″) Slide 1, 16″ x 16″

Slide 1, 16″ x 16″ Slide 2, 16″ x 16″

Slide 2, 16″ x 16″ Slide 3, 16″ x 16″

Slide 3, 16″ x 16″ Slide 4, 16″ x 16″

Slide 4, 16″ x 16″

Image 1. Canada (2014)

Image 1. Canada (2014) Image 2. State Route (2014)

Image 2. State Route (2014) Image 3. Wave (2015)

Image 3. Wave (2015) Image 4. Michigan (2016)

Image 4. Michigan (2016) Image 5. Neighbors (2016)

Image 5. Neighbors (2016) Image 6. Parking Lot (2016)

Image 6. Parking Lot (2016) Image 7. Window (2015)

Image 7. Window (2015) Image 8. Corner Lot (2016)

Image 8. Corner Lot (2016) Image 9. Development (2015)

Image 9. Development (2015) Image 10. Thoroughfare (2015)

Image 10. Thoroughfare (2015) Image 11. Canal (2016)

Image 11. Canal (2016) Image 12. Strip Mall (2014)

Image 12. Strip Mall (2014) Image 13. Resort (2015)

Image 13. Resort (2015) Image 14. Mountainside (2015)

Image 14. Mountainside (2015) Image 15. Beach Day (2016)

Image 15. Beach Day (2016) Image 16. Light Cubes (2016)

Image 16. Light Cubes (2016) Movement Is The Antechamber Of Hallucination 32” x 40” 28.3.2016

Movement Is The Antechamber Of Hallucination 32” x 40” 28.3.2016 And still the navigators 38’ x 38” 27.6.2016

And still the navigators 38’ x 38” 27.6.2016

Five Ravens

Five Ravens

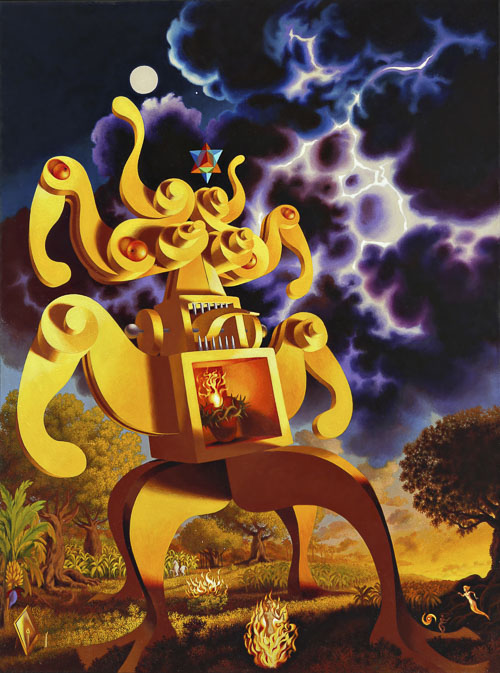

Brave New Whorl

Brave New Whorl Nautilus

Nautilus Spectre

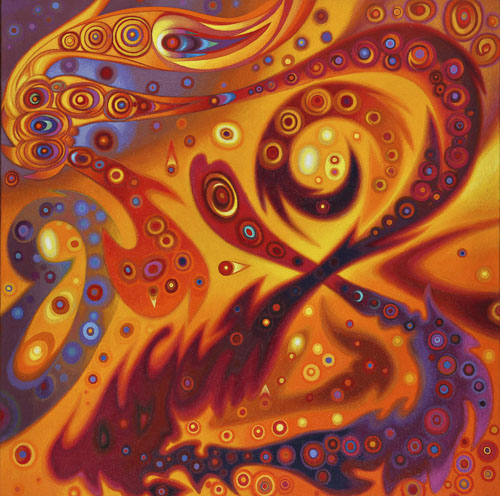

Spectre Tipping Point

Tipping Point Transcendence

Transcendence Butterfly

Butterfly

Dilasa is ten years old. She was born in a Nepali refugee camp and came to the United States when she was five. Her parents are Bhutanese refugees.

Dilasa is ten years old. She was born in a Nepali refugee camp and came to the United States when she was five. Her parents are Bhutanese refugees. Lynne M. Browne at two.

Lynne M. Browne at two. Guman is Bhutanese-Nepali

Guman is Bhutanese-Nepali Members of the Utica Don Dancers go to many cultural events in the area and perform the traditional Karen New Year dance. KuSay (pictured) is Karen, from Burma.

Members of the Utica Don Dancers go to many cultural events in the area and perform the traditional Karen New Year dance. KuSay (pictured) is Karen, from Burma. More from the traditional Karen New Year dance.

More from the traditional Karen New Year dance.

Born in the U.S., Shayal is Bhutanese-Nepali.

Born in the U.S., Shayal is Bhutanese-Nepali. Monisha came to the United States in 2014 from a refugee camp in Jhapa, Nepal. Her family occupied one of the lower social groups in the Hindu caste system, but converting to Christianity and coming to the U.S. freed her family from the discrimination of their former position. Monisha is a high school student and loves traditional Nepali and contemporary Hindi-style dance. This photograph was taken only a few days after her arrival.

Monisha came to the United States in 2014 from a refugee camp in Jhapa, Nepal. Her family occupied one of the lower social groups in the Hindu caste system, but converting to Christianity and coming to the U.S. freed her family from the discrimination of their former position. Monisha is a high school student and loves traditional Nepali and contemporary Hindi-style dance. This photograph was taken only a few days after her arrival. Layla is a teenager from Somali-Bantu who has a quick wit and wants to be a model some day; she commands a room when she is present.

Layla is a teenager from Somali-Bantu who has a quick wit and wants to be a model some day; she commands a room when she is present. Amina (L) and Zeinabu (R) are Somali-Bantu refugees who were resettled to Utica from one of the largest and most dangerous refugee camps in the world, Daadab in Kenya. They have been in the U.S. for approximately 14 years and are now high school students and fans of Korean drama and K-pop, Korean popular music.

Amina (L) and Zeinabu (R) are Somali-Bantu refugees who were resettled to Utica from one of the largest and most dangerous refugee camps in the world, Daadab in Kenya. They have been in the U.S. for approximately 14 years and are now high school students and fans of Korean drama and K-pop, Korean popular music. This portrait was taken while three generations of women were enjoying cultural performances and visiting exhibits at the Utica Zoo.

This portrait was taken while three generations of women were enjoying cultural performances and visiting exhibits at the Utica Zoo.

Bill Hayward

Bill Hayward Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan Fragment A (from the film Asphalt, Muscle & Bone)

Fragment A (from the film Asphalt, Muscle & Bone) Broken Odalisque

Broken Odalisque Al Pacile (from The Human Bible)

Al Pacile (from The Human Bible) Dragon Smoke Behind Tree

Dragon Smoke Behind Tree