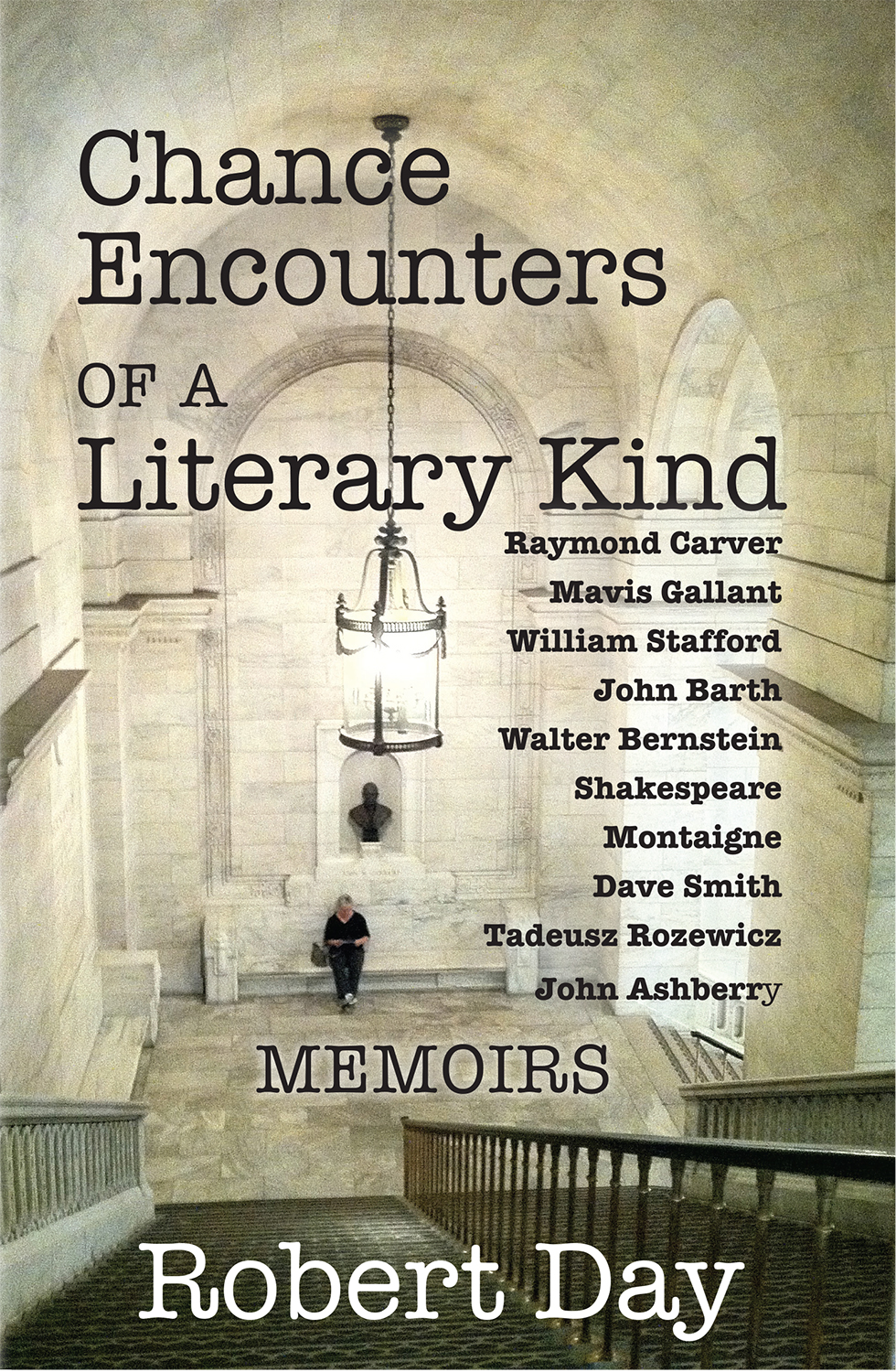

Numéro Cinq is always an adventure, a game of firsts. The first this, the first that. Now Robert Day‘s essay series Chance Encounters of a Literary Kind is being published (the end of the month) by Serving House Books and that is a first of a high order, the first ever book composed entirely of work that appeared in Numéro Cinq first (you can see I am obsessing on the word “first”). This is a proud moment for the whole community and an inspiration to the many who have contributed regularly and brilliantly to the magazine. I foresee more such NC-inspired books. (Actually, Robert Day’s novel, Let Us Imagine Lose Love, first serialized on NC, will be published in the fall as well, but I will do a separate announcement about that at the appropriate moment. The man is on a roll!)

I wrote an introduction — entitled “Exit, Pursued by a Bear” — for the Serving House Books edition, an honour and a pleasure (he opines) that you all get to share right now.

§

Exit, pursued by a bear

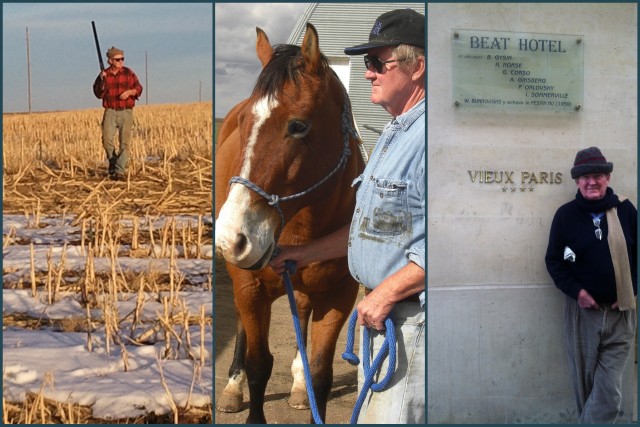

Robert Day and I met something like 35 years ago in a University of Iowa classroom. He was the teacher, I was a student. He strode into the room and proceeded to the blackboard where he wrote, in large capital letters, from one side of the room to the other: REMEMBER TO TELL THEM THE NOVEL IS A POEM. Outside of class we got to know each other a bit. He once said, pressing the elevator button instead of climbing one slight of stairs, that if God had meant us to use stairs he would not have invented elevators. I was on the cusp of a truly disastrous relationship just then. Day said to me, “Get out of there. For every day you spend with her now, it’ll take you another year to get out of it.” Ask me if I listened to him. One afternoon we spent kicking tires at a Jeep dealership. And one day he talked to me about the novel I was working on, a conference that must have lasted all of 20 minutes but somehow managed to open up the novel and show me its hot, beating heart, which hitherto had failed to reveal itself to me. That was a lesson I did listen to.

Now, many, many, many years later we have congregated again through the magical intervention of the Internet and the online magazine I materialized Numéro Cinq. We hadn’t been in touch in years; we still haven’t actually seen each other since 1981. But we continue to exert gravitational force upon each other’s lives in ways that are astonishing and delightful. The long and short of it is that I began to publish Robert Day. A short story first. Later the story became a novel. I published the entire novel. Then I published a memoir about his mother, a tender, sweet essay about her suspicion of the French, Day’s love of Montaigne, and the summer she died while he was traveling in France.

Then Day invented a new form, the Chance Encounters of a Literary Kind essays, brief, whimsical, sometimes touching, reminiscences about his brushes (often friendships) with literary greatness. The first one he wrote and tried out on me was about the poets John Ashbery and Tadeusz Rozewicz. He didn’t meet them; they met in his mind, and in a conversation with a friend over a kitchen table in Kansas. But the collision was sparkling in its reverent irreverence and the insights spawned in the erotics of juxtaposition. But it was also airy, gossamer-thin, a playful and informal thing, a little jeu d’esprit that took itself not very seriously, yet with flashes of seriousness and wit. Day asked me if I wanted more of these. He projected a series. He made a list. He wrote: “I’d like to keep the “Chance encounters” real–that is, what I stumble into or on to as I lead my literary life; there should be x of them the rest of the year because I poke around in these matters often these days, and, like any fiction writer, stories (and chance literary encounters) happen to me.

I have my favorite moments. Day and Raymond Carver quoting Jack London back and forth to each other. Day’s sweet evocation of the life-philosophy of poet William Stafford, who once advised his young daughter, “Talk to strangers.” This is in an essay that goes on to ponder our current Age of Fear, the prevalence of surveillance, and our willingness to submit to precautions that cheat us of human relations.

I also adore Day’s piece on screenwriter Walter Bernstein, especially Day’s expert interventions in an early script for the movie The Electric Horseman. Day being from Kansas, Bernstein considered him the expert on cowboys and horses. “Somehow Walter had learned the word hackamore (probably from an East Coast riding friend) and so I had to take the hackamore off all horses and put bridles and bits back in their mouths.” And, of course, the “Exit, pursued by a bear” stage direction from The Winter’s Tale that pops up unbidden and like fireworks in Day’s essay on Sarah Palin and going to see a production of Coriolanus.

The buzzword these days for someone who wanders about poking idly into things (and being brilliant and witty about them) is flâneur. But when I read Day’s essays I think, not of Walter Benjamin, but of the waggish early 18th century essays of Joseph Addison and Richard Steele and the journals they published, The Tatler and The Spectator, whose purpose it was “to enliven morality with wit; and to temper wit with morality.” Day’s essays are intelligent, literate conversation at its best—all too rare these days—written with aplomb in the author’s trademark amiable and self-ironic style.

—Douglas Glover

Pinckney Benedict via

Pinckney Benedict via

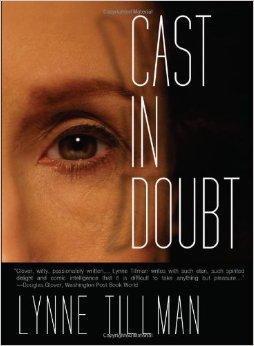

Lynne Tillman by David Shankbone.

Lynne Tillman by David Shankbone.

Yves Klein via Wikipedia

Yves Klein via Wikipedia Sam Shelstad and dg at the Open Space Gallery, Victoria. Photos by Miles Giesbrecht.

Sam Shelstad and dg at the Open Space Gallery, Victoria. Photos by Miles Giesbrecht.

Back Cover

Back Cover

At the end of the Victoria trip, dg spent an afternoon with the Coast Salish master carver Charles W. Elliott in his studio at the Tsarlip First Nation Reserve on the Saanich Peninsula north of the city. Above is a thunderbird atop of a Charles Elliott totem pole in front of the ȽÁU, WELṈEW̱ Tribal High School just down the road from the studio.

At the end of the Victoria trip, dg spent an afternoon with the Coast Salish master carver Charles W. Elliott in his studio at the Tsarlip First Nation Reserve on the Saanich Peninsula north of the city. Above is a thunderbird atop of a Charles Elliott totem pole in front of the ȽÁU, WELṈEW̱ Tribal High School just down the road from the studio. Charles W. Elliott holding a print he designed as a symbol for the

Charles W. Elliott holding a print he designed as a symbol for the

Here’s the school front. Note the repetition of the structure: thunderbird on top of the pole, thunderbird on the from wall of the building, and the structure of the building as a whole is a thunderbird with wings. What you can’t see from the angle is that before the front door is an entryway in the shape of a bird again. To get into the school, students pass beneath the thunderbird’s wings. Also not the bracket shapes along the roof line. And then think what a lively public art form this is.

Here’s the school front. Note the repetition of the structure: thunderbird on top of the pole, thunderbird on the from wall of the building, and the structure of the building as a whole is a thunderbird with wings. What you can’t see from the angle is that before the front door is an entryway in the shape of a bird again. To get into the school, students pass beneath the thunderbird’s wings. Also not the bracket shapes along the roof line. And then think what a lively public art form this is.

This is Elliott’s studio with a huge ocean-going dugout canoe made of old growth cedar, a work in progress. On the left is the base of a new totem pole.

This is Elliott’s studio with a huge ocean-going dugout canoe made of old growth cedar, a work in progress. On the left is the base of a new totem pole. Studio again. Note the Che Guevara image, one of several, in the studio, also mentioned by Elliott. You can’t forget that the natives are a colonized and dispossessed people who wake up every morning and look around and see commuters racing up the highway to a city that covers the land that was once theirs spiritually and economically, land they never gave away in any sense proper to their own culture and way of thinking. Put yourself in their shoes. As Elliott said, it’s as if there is a constant cloud or blanket of colonization over the natives. How they could they forget and be pleased?

Studio again. Note the Che Guevara image, one of several, in the studio, also mentioned by Elliott. You can’t forget that the natives are a colonized and dispossessed people who wake up every morning and look around and see commuters racing up the highway to a city that covers the land that was once theirs spiritually and economically, land they never gave away in any sense proper to their own culture and way of thinking. Put yourself in their shoes. As Elliott said, it’s as if there is a constant cloud or blanket of colonization over the natives. How they could they forget and be pleased?  Little things all over the studio. Here’s a spinning fish lure in the shape of an octopus, the legs scalloped with those bracket patterns. Everything comes to life in this art world, inanimate objects, utilitarian objects.

Little things all over the studio. Here’s a spinning fish lure in the shape of an octopus, the legs scalloped with those bracket patterns. Everything comes to life in this art world, inanimate objects, utilitarian objects. So here’s a bronze spindle whorl (traditionally they were made of wood) made by Elliott’s 19-year-old son, Chas Elliott, who is learning the art from his father and brought this over to show us. If I remember correctly this is a seal (but I heard so much I might be misremembering). Mouth in the spindle opening. Flippers or paws to the side. Flippers accented with eye and bracket and lanceolate shapes.

So here’s a bronze spindle whorl (traditionally they were made of wood) made by Elliott’s 19-year-old son, Chas Elliott, who is learning the art from his father and brought this over to show us. If I remember correctly this is a seal (but I heard so much I might be misremembering). Mouth in the spindle opening. Flippers or paws to the side. Flippers accented with eye and bracket and lanceolate shapes.  DG with a “talking stick” (you would hand this to someone who would then hold the floor whole others listened). By now you should be able to distinguish some of the motifs and design elements.

DG with a “talking stick” (you would hand this to someone who would then hold the floor whole others listened). By now you should be able to distinguish some of the motifs and design elements. Outside the studio looking at a totem pole in for repair after about 20 years in the field. Totem poles don’t last forever, obviously. This one needs to be shaved down to fresh wood and repainted. And there is some rot at the top that needs digging out and a plug put in. A sad thing is that native carvers like Elliott can only work with old growth timber. For some reason, the old growth trees grew slower, their tree rings are much closer together, and the wood is harder and more durable. Newer trees seem to grow faster (perhaps because they get more light), the rings are farther apart and the wood between is “punky.” There is hardly any old growth timber left. I won’t go on. This is just a taste of the visit with Elliott, an immense privilege, not to mention fascinating; I could go on and on.

Outside the studio looking at a totem pole in for repair after about 20 years in the field. Totem poles don’t last forever, obviously. This one needs to be shaved down to fresh wood and repainted. And there is some rot at the top that needs digging out and a plug put in. A sad thing is that native carvers like Elliott can only work with old growth timber. For some reason, the old growth trees grew slower, their tree rings are much closer together, and the wood is harder and more durable. Newer trees seem to grow faster (perhaps because they get more light), the rings are farther apart and the wood between is “punky.” There is hardly any old growth timber left. I won’t go on. This is just a taste of the visit with Elliott, an immense privilege, not to mention fascinating; I could go on and on. Surprisingly, there are great swathes of clear cut forest all along the coastal road in the west. Sometimes the lumber companies leave a thin screen of trees along the road and sometimes not. Depressing to see. Most of the logs go straight to China these days.

Surprisingly, there are great swathes of clear cut forest all along the coastal road in the west. Sometimes the lumber companies leave a thin screen of trees along the road and sometimes not. Depressing to see. Most of the logs go straight to China these days. Sombrio Beach (photo by MF). Behind us, makeshift tents and campsites occupied by surfers trying to dry out in the dense mist.

Sombrio Beach (photo by MF). Behind us, makeshift tents and campsites occupied by surfers trying to dry out in the dense mist. The Juan de Fuca Trail near Sombrio Beach.

The Juan de Fuca Trail near Sombrio Beach. DG at the University of Victoria First Peoples House as a guest of

DG at the University of Victoria First Peoples House as a guest of

Harbor seal off the marina wharf in Mill Bay. They were playing all along the coast, some far out and diving with dramatic tail slaps. At Mill Bay we heard the tail slaps, saw loons and a kingfisher and then a bald eagle zoomed close overhead, all in about five minutes. DG stopped mentioning the seals to the locals because it marked him as a greenhorn.

Harbor seal off the marina wharf in Mill Bay. They were playing all along the coast, some far out and diving with dramatic tail slaps. At Mill Bay we heard the tail slaps, saw loons and a kingfisher and then a bald eagle zoomed close overhead, all in about five minutes. DG stopped mentioning the seals to the locals because it marked him as a greenhorn. Cow Bay, a touristified, single-street, old village on the coast, organic foods, organic baked goods, and one store that sold liquor and tools.

Cow Bay, a touristified, single-street, old village on the coast, organic foods, organic baked goods, and one store that sold liquor and tools. This is the so-called butter church on Comiaken Hill in the Cowichan Reserve, Cowichan Bay in the background to the right. Abandoned, it was the first church in the area, an ancient-looking chapel, on a hill that feels lonely, mysterious and sacred, empty grass field to the left where people were once buried, though most of the markers are down, one lone oak tree, low mountains all around except in the direction of the bay. Also a place of ill-memory because of treaties signed nearby in the 1850s. The church was built in 1870 with the help of natives who were paid with money earned from the sale of butter. Apparently.

This is the so-called butter church on Comiaken Hill in the Cowichan Reserve, Cowichan Bay in the background to the right. Abandoned, it was the first church in the area, an ancient-looking chapel, on a hill that feels lonely, mysterious and sacred, empty grass field to the left where people were once buried, though most of the markers are down, one lone oak tree, low mountains all around except in the direction of the bay. Also a place of ill-memory because of treaties signed nearby in the 1850s. The church was built in 1870 with the help of natives who were paid with money earned from the sale of butter. Apparently.

St. Anne’s Church, just down the road from the butter church. Back in Victoria we had run into an ancient beekeeper who said his great- or great-great-grandfather was Chief George Tzouhalem of the Cowichan band. An Irishman who fought with Pickett at Gettysburg apparently came up the coast and married the chief’s 15-year-old daughter — this was the beekeeper’s line. He said to drive up to this place because old chief Tzouhalem is buried here and his grand-daughter bought a pink granite plinth and had it raised over the grave. We walked all through this sombre place and finally, yes, did discover the plinth, raised by the grand-daughter Ettie George, just as the beekeeper had said. He had known Ettie and had stories.

St. Anne’s Church, just down the road from the butter church. Back in Victoria we had run into an ancient beekeeper who said his great- or great-great-grandfather was Chief George Tzouhalem of the Cowichan band. An Irishman who fought with Pickett at Gettysburg apparently came up the coast and married the chief’s 15-year-old daughter — this was the beekeeper’s line. He said to drive up to this place because old chief Tzouhalem is buried here and his grand-daughter bought a pink granite plinth and had it raised over the grave. We walked all through this sombre place and finally, yes, did discover the plinth, raised by the grand-daughter Ettie George, just as the beekeeper had said. He had known Ettie and had stories.

Christianity is dissipating perhaps. The crosses all over the graveyard were mostly temporary markers. Occasionally, there was something more indicative of a different way of being. Later, I got to talk to a man who makes the grave markers, a social role passed down through his family, and he said the crosses are just places to put names now, not signs of belief. Alarming number of fresh graves in every native graveyard, signs of hard lives, poverty and the depression that goes with being a dispossessed and colonized people.

Christianity is dissipating perhaps. The crosses all over the graveyard were mostly temporary markers. Occasionally, there was something more indicative of a different way of being. Later, I got to talk to a man who makes the grave markers, a social role passed down through his family, and he said the crosses are just places to put names now, not signs of belief. Alarming number of fresh graves in every native graveyard, signs of hard lives, poverty and the depression that goes with being a dispossessed and colonized people.