Alameddine uses the structure of his novel—as Proust did—to recreate the impression of memory. The Angel of History, with its fragmented, alternating, multiple points of view and multiple plots is a structural triumph, not in spite of these qualities, but because of them. —Frank Richardson

The Angel of History

Rabih Alameddine

Atlantic Monthly Press, 2016

304 pages, $26.00

.

What if you were Satan’s chief delight? How chilling, how disturbing, how psychosis-inducing would it be to discover Satan—yes, the actual devil, Mephistopheles, the Morning Star, Lucifer—said that you rejuvenated his jaded heart? Who would want to know that? In The Angel of History, Rabih Alameddine’s newest novel, we learn the answer to this question, for Jacob, a Yemeni-born poet and survivor of the AIDS epidemic, is Satan’s delight, and the fallen angel makes it his mission to rescue Jacob from forgetting his past.

The Angel of History is Rabih Alameddine’s sixth book and fifth novel. Born in Amman, Jordan, he spent his youth in Kuwait and Lebanon. After moving to the United States, he first pursued an engineering career, but gave that up for painting, and then writing. In 1998 he published his first novel, the critically acclaimed Koolaids, a blistering indictment of war and a harrowing examination of the ravages of AIDS. His other novels include the experimental I, The Divine: A Novel in First Chapters (2001), The Hakawati (2008), which draws on the tradition of Arabian fables, and the bibliophile’s delight, the sublime An Unnecessary Woman (2014), which won the California Book Award Gold Medal for Fiction and was a finalist for the National Book Award.

Now fifty-six, Alameddine spends his time between San Francisco and Beirut. Once again exploring the subjects of AIDS and war in the Middle East, with The Angel of History, Alameddine gives us provocative storytelling at its finest, a fabulist tale that explores how we grieve and how we succeed and fail in confronting our most painful memories.

Jacob’s Elegy

Ya‘qub, the protagonist and narrator of two-thirds of The Angel of History, arrives one rainy night at a crisis psychiatric clinic in San Francisco determined to be admitted. The fifty-something Ya‘qub has used the Americanized ‘Jacob’ since moving to San Francisco in the 1980s as a young man. Jacob explains to the triage nurse that he has been suffering from hallucinations again and is depressed. His employer had suggested he seek counseling, but it wasn’t until Jacob saw a report of another U.S. drone-strike on a Yemeni village, this time his mother’s hometown, perhaps the one where he was born, that he finally broke down. He needs an emotional holiday, and his ideal version would be three days in the psychiatric unit of Saint Francis Hospital with a nice Haldol-Ativan cocktail served with a chaser of Lexapro—after all, drugs had helped before—something to quiet the voices, something to deaden the pain, something to turn out the light of memory.

The majority of the 300-page novel is arranged in three titled sections—“Satan’s Interviews,” “Jacob’s Journals,” and “At the Clinic”—each of which is divided into twelve chapters, many with titled subchapters. Alternating in sequence, the three major sections present three parallel plots from multiple points of view providing a nonlinear reconstruction of Jacob’s history.

A poet who earns a living as a word processor for a law firm, Jacob lives alone in his San Francisco apartment except for his large black cat, Behemoth, whom he named specifically after the infernal feline in Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita—another novel featuring a well-tailored Satan. Jacob suffers survivor’s guilt. All of his friends, including his beloved partner Doc, died from AIDS-related diseases twenty years ago during the height of the epidemic in the late 1980s. Overcome with anguish for his lost friends, Jacob hasn’t been able to write poetry for some time, but his old muse, his “angel of remembrance,” Satan, has returned.

The primary plot of the novel, set in the notional present and narrated by Jacob in the “At the Clinic” chapters, covers his breakdown the night he seeks admission to the hospital. Jacob’s narration is often in a stream of consciousness style, mimicking thought, as in this example where he explains the reappearance of Satan in his life:

It has been getting worse, Doc, I don’t seem to be able to cut him off, I am all wound with adders who with cloven tongues do hiss me into madness, it wasn’t always this bad, I went along for years doing rather well, didn’t hear his voice, but then one day he reappeared, and he’s been getting more demanding, more irksome, hissing, hissing, and I get headaches, I fear the return of the great migraine storms, I need a break, Doc, I need a break.

Devastated when his friends died, Jacob spent time as an inpatient in the same hospital to which he is once again applying. He had thought he was stable, he had thought he had escaped the trauma of history: of losing his friends and his mother and the memories of his childhood. As he writes in his journal, always addressing Doc:

While my mind processed the chaos that passes for thought in the early morning, I had cracked five eggs by the time I realized I was about to make you an omelet as well. Decades may have passed and sometimes it feels like only yesterday that we had our breakfast together. . . . I’d had a life since you left . . . I did yoga . . . I went to art openings . . . I watched bad television shows . . . I was living, I thought I was content, I was told I was happy. I did a marvelous impression of a man not crushed by dread.

Moments such as these reveal Jacob’s deep grief and give the impression of a hollowed out life. Jacob’s tender admission evokes the tone of Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man, another novel that addresses living day-to-day with heartache for a lost partner.

“Jacob’s Journal” is part requiem, part confession, and it is also where we learn what Jacob remembers about his mother, a teenage Yemeni maid who became pregnant by the equally young son of her wealthy employers in Beirut. Kicked out, she becomes a homeless wanderer through squalid desert villages where she is forced into prostitution. Mother and child finally settle in a Cairo whorehouse for the most stable and in many ways happiest time of Jacob’s childhood. But these memories have been repressed, or lost, or ignored for too long. Jacob writes about his childhood:

You, Doc, wait, I need someone to hear this, listen to me. . . . I don’t know why I tell you all this about me, I need to, I guess, but with this need to tell comes the concomitant desire to forget everything . . .

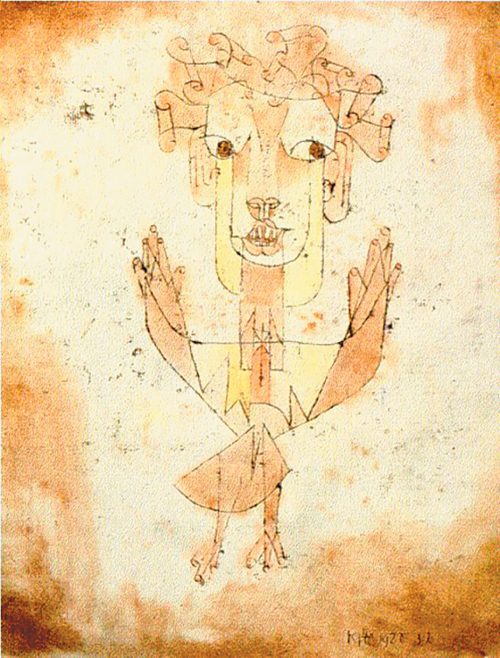

An assiduous Satan has been working against Jacob’s “desire to forget,” and Jacob’s journal and ensuing breakdown have been the result. In an allusion to Walter Benjamin’s commentary on Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, Jacob tells a bartender, “I am your angel of history”; namely, a being who sees the past as a single, unalterable catastrophe.

Paul Klee: Angelus Novus, 1920

Paul Klee: Angelus Novus, 1920

Angels and Ministers of Grace

The most significant subplot of The Angel of History unfolds in “Satan’s Interviews” and involves Satan’s attempt to rescue Jacob from forgetting his past. One of the most entertaining, often hilarious, and clever parts of the novel, “Satan’s Interviews” features third-person omniscient narration, usually limited to Satan’s locus of perception.

Being supernatural, Satan simultaneously coaxes Jacob to leave the clinic and hosts interviews with his son, Death, and a group of Catholic saints at Jacob’s apartment. The devil has a long tradition in literature, with some of the most memorable and most human versions found in Milton, Goethe, and Bulgakov. Alameddine’s Satan is eerily human with a voice as beguiling as one might expect from the personification of temptation. Jacob does a fine job describing Alameddine’s Satan (in a sly metafictional stroke) when he writes in his journal how Doc “endowed the devil with wickedness and perseverance, you made him fun, witty, intelligent, frisky, lively, ironic, and above all, petty, all too human, like us.” But for Jacob Satan is Iblis, Islam’s whispering jinn, a sulking, lonely creature with nothing better to do than torment him.

Satan is a fully realized character, complete with his own conflicts and a clear desire: he wants Jacob back. During Jacob’s first hospitalization he was drugged to near catatonia, and after leaving the hospital he spent many years on antidepressants and a variety of pharmaceuticals, both legal and otherwise. Satan doesn’t want his favorite whipping boy tumbling down that rabbit hole again.

In the first of “Satan’s Interviews” Death—whimsical, mocking, irreverent—asks his father why he is intervening in Jacob’s life now; Satan replies: “Because he has been sleepwalking through life since his friends died, because he has been so lonely without me, because his poems were getting more and more boring, his dreams more banal, and worst of all, he began to write stories.” However, it could be worse, Satan concludes, horror of horrors, Jacob “could write a novel.” Satan’s motivation, ostensibly for the benefit of Jacob’s art, is, not surprisingly, purely selfish: Jacob “rejuvenates my jaded heart” Satan confesses to Saint Blaise. Furthermore, Satan tells Jacob that it was him, not the saints, who saved Jacob from AIDS:

funny you should credit the silly saints with healing you, and not me, Death came for you and I intervened . . . I sat him down, told him your soul was mine, a long time ago I claimed you, you child of pestilence, you squashable worm . . .

And this is part of Satan’s interest in Jacob, namely Jacob’s squashability—most clearly reflected in his sexual history. Jacob’s experience with sex begins violently when a customer of the Cairo whorehouse demands that the ten-year-old paint henna on his penis. In his Lebanese boarding school Jacob is beaten and repeatedly humiliated by bullies. As an adult in San Francisco, jealous of Doc picking up another man, Jacob visits an S&M club where he is whipped—and it will not be his last indulgence in masochism.

Death asks Satan if he is going to interview “the others”—meaning the saints that Jacob prayed to as a child and as an adult until AIDS took everyone from him. In a Catholic tradition dating to the Black Plague, there are a group of fourteen saints—known as the Fourteen Holy Helpers—who are prayed to for specific maladies. Satan doesn’t interview all fourteen, but he does call upon them, remarkably, for assistance. It seems that Satan has done his job all too well in helping Jacob remember and now he needs help in keeping Jacob sane and off memory-impairing medication. Death, whose job is to offer the cup of forgetting, the waters of Lethe, expects Jacob will choose him, and so the dance between remembrance and oblivion begins.

In his depiction of the saints, Alameddine shows us compassionate but weary caregivers, for eternity is long and people exasperating. The interviews also offer humorous, welcomed breaks from Jacob’s somber memories. For example, Satan is unnerved by Saint Denis holding his decapitated head in his lap and insists he return it atop his neck, and Saint Margaret mocks Satan by holding a balloon of a baby dragon, for according to legend, Satan, in the form of a dragon, swallowed her but then choked on her cross. It is Saint Margaret who asks Satan to bring Jacob back to poetry: “A poet is tormented by the horrors of this world, as well as its beauty, but he can be refreshed, reborn even; he can take to the sky once more.” Saint Catherine sympathizes with Jacob’s past choices, she feels he only “did what he had to do during the time of sunder, he girded himself against the dirge,” but in the present she agrees with Satan’s assessment: “We must wake him and hazard the consequence. We must offer the apple.”

Tilman Riemenschneider workshop, The Fourteen Holy Helpers, c. 1520

Tilman Riemenschneider workshop, The Fourteen Holy Helpers, c. 1520

War All the Time

In addition to the three major divisions of the novel, there are three sections labeled “Jacob’s Stories,” each containing a single short story independent of (but harmonizing with) the novel’s plot. The elegiac tone of Jacob’s journal changes to bitter resentment when he thinks of the humiliating final stages of his friends’ suffering, and his anger, inflamed by the interminable carnage he witnesses in the land of his birth, is vented in his stories.

Alameddine displays a formidable gift for satire in “Drone” and “A Cage in the Penthouse.” The latter, reminiscent of George Saunders’s equally acerbic “The Semplica-Girl Diaries,” features a wealthy couple who keep a caged Arab as a pet in their Manhattan penthouse. In “Drone” we see U.S. drone strikes through the point of view of a sentient, self-righteous attack drone named Ezekiel.

Through Jacob’s thoughts and his stories, Alameddine reminds us how easily wars are forgotten. Indeed, one of the epigraphs is from Milan Kundera (a writer who has had much to say about war and memory): “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” War tears through the countries of the Middle East daily, and for Alameddine—who grew up in Lebanon and spends much of his time there—this subject runs through his fiction like a scar.

Finding Time Again

The Angel of History shares more than a few characteristics with that paragon of memory novels, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, and Jacob’s past is what Satan and the saints are there to help him find and keep. Alameddine’s talent for nonlinear narrative—evident in Koolaids where the Lebanese civil war is starkly juxtaposed with the AIDS epidemic—shines brightest in The Angel of History with its exquisitely interlaced chronology, multiple plots, and points of view.

“Jacob’s Journals” presents a conventional memoir: Jacob thinking about his past. “At the Clinic” is more complex; here Jacob is thinking about his present, past, and future, but the narration feels like an extension of his journal, as if the events of his night at the clinic are added to his journal in the future. Satan’s interviews take place concurrently with Jacob’s night at the clinic but tell the story of Jacob’s mother and his childhood through the saints’ recollections. Satan’s imperative to the Fourteen Holy Helpers is clear: “What I hear he remembers . . . Remind him of himself.” Each interviewee recalls different parts of Jacob’s history which Satan then channels to Jacob. The ingenious conceit of the interview chapters is that, given the supernatural nature of the interlocutors, time is irrelevant and all the interviews can be simultaneous in an eternal moment. Furthermore, in these chapters Alameddine uses third-person, taking advantage of a wider range of point of view. These shifting times and points of view reveal Jacob’s memories in manner much like the actual process of remembering, a process during which we often take two steps back for every step forward.

Alameddine leaves little doubt about his admiration for Proust’s fiction in An Unnecessary Woman. Here as well, Proust informs Alameddine’s novel, from the simple homage—naming Jacob’s roommate Odette—to more direct references. For example, Jacob has moments of involuntary memory, such as in a grocery store where “the mephitic aroma of disinfectant assaulted my senses, and you jumped the levee of my memory. Proust had his mnemonic madeleine, but bleach was all ours, Doc, all ours.” Note, Alameddine doesn’t miss an opportunity to layer his images, here alluding to Mephistopheles. But to emphasize such references, as fun as they are, would be to neglect the genuine beauty of how Alameddine uses the structure of his novel—as Proust did—to recreate the impression of memory. The Angel of History, with its fragmented, alternating, multiple points of view and multiple plots is a structural triumph, not in spite of these qualities, but because of them.

§

In An Unnecessary Woman, Aaliya pleads with writers to “Have pity on readers who reach the end of a real-life conflict in confusion and don’t experience a false sense of temporary enlightenment.” Rabih Alameddine is not a fan of epiphanic endings, and you won’t find one here. The Angel of History asks questions and raising issues for which there are no simple answers. Is ignorance bliss? Can we deny our past? Should we try? The Angel of History tasks us with the necessity of facing our memories, even the most painful ones, for to neglect them is to surrender to Death, to drink from the river Lethe, to become complacent drones (pun intended). Alameddine’s book is a statement on memory, on surviving loss, on war and disease and how we cope with them, and finally on art; and that poetry, or any art, cannot exist in a memoryless (and thus painless) vacuum.

On his walk home from the clinic through the nighttime streets of San Francisco, Jacob stops to write impromptu poems and statements on storefronts he remembers from happier times; on a No Parking sign he writes:

You all dead

I still walk

Therefore I am

I know it is so

For I long

I long for solace

How does one find such

Among so many ashes?

Jacob’s question cannot be resolved in a single moment of enlightenment, and like him, we too must confront our losses, for there is no solution to grief other than learning how to live with a shadow of hell.

—Frank Richarson

N5

Frank Richardson lives in Houston and received his MFA in Fiction from Vermont College of Fine Arts. His poetry has appeared in Black Heart Magazine, The Montucky Review, and Do Not Look At The Sun.

.

.

Five Ravens

Five Ravens

Brave New Whorl

Brave New Whorl Nautilus

Nautilus Spectre

Spectre Tipping Point

Tipping Point Transcendence

Transcendence Butterfly

Butterfly