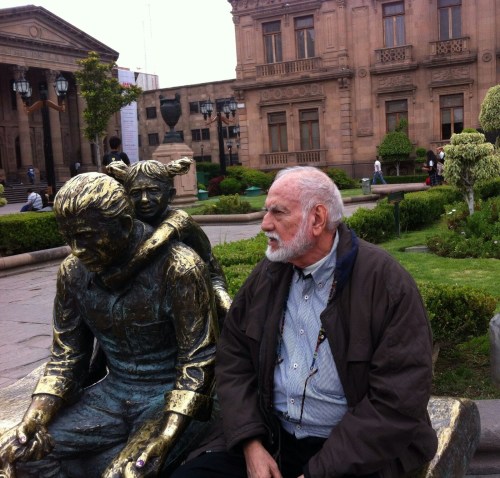

Cid Corman & Gregory Dunne

Cid Corman & Gregory Dunne

Cid Corman was born in Roxbury, Boston, in 1924. His seminal magazine Origin was one of the first to publish poets such as Charles Olson, Gary Snyder, Denise Levertov, and Robert Creeley. In addition to the magazine, Cid, a poet and translator, organized poetry events around Boston and started the country’s first poetry radio program, This Is Poetry at WMEX featuring readings by Creeley, Stephen Spender and Theodore Roethke amongst others. In 1958 he moved to Japan where he continued to edit Origin and in 1959 published Gary Snyder’s first collection Riprap. He began to translate Japanese poetry, in particular work by Basho and Kusano Shimpei. A prolific poet, he published over a hundred books and pamphlets. In 1990 he published the first two volumes of his selected poems Of. In all there are five volumes each containing 750 poems. Volumes 4 and 5 were just published in January of this year. Although described as a selected poems, Corman did not necessarily see it that way. He saw it as a single book that told his life in passing. Cid Corman died in Kyoto on March 12, 2004.

I am grateful to Greg Dunne, not just for the extract from his new book but for the wonderful opportunity he gave me back in 2000 to spend an afternoon visiting with Corman in his home in Kyoto. I had been travelling with my wife and young children in China for several months and stopped off in Japan on the way back to visit Greg. Over the years I had heard the story many times of how after moving to Kyoto Greg had stopped in at a coffee shop, CC`s, that sold western style ice-cream and cakes. The shop turned out to be Corman’s and Greg soon joined with a small group that met with him every two weeks for gatherings that lasted five hours or more. Cid read and talked poetry with them, discussed their work.

That afternoon, however, we talked to Corman about his work and his life. I got the feeling that he liked visitors so that he could relate the stories of his past to them, and through those stories reaffirm his true relevance to American poetry. This seemed to me to be borne of disappointment, sadness even – an awareness that his decision to live in Kyoto had left him largely forgotten in his home country. Nevertheless, it was evident that deep-down he knew that the poet’s life was exactly that – a life, a way of living. And he talked that day too of not even wanting his name on his poems at all, at refusing publicity when it occasionally came his way.

He excused himself at one point and left the room briefly returning with a copy of the first issue of Origin. He was proud of it, and rightly so. He spoke then of his writing routine. His morning began by writing letters, long letters to anyone who had taken the time to write to him. “If you write to me,” he told me, “I will write back.” After his letter writing he began work on his poems. He took me in to see his study. It was stacked high with manuscripts, heaps of paper across his desk and all around the room. “I write a book of poems a day,” he said. Most of these pages would probably never see the light of day. The act of writing to him, it appeared, was akin to the act of breathing – a breath in/a breath out, a word given/a word taken. This was not a rushed process; it was not a mountain of first drafts, of beginnings, but an ongoing expression of self.

Later we took a pleasant walk to the post-office to mail off his letters and then said our goodbyes. Despite his generous offer, I never did write to him. I regret it enormously of course but, in some ways these feelings of regret seem apt – a more fitting response to our short afternoon together.

—Gerard Beirne

.

What is theoretically innovative, and politically crucial, is the need to think beyond narratives of originary and initial subjectivities and to focus on those moments or processes that are produced in the articulation of cultural differences. These ‘inbetween’ spaces provide the terrain for elaborating strategies of selfhood – singular or communal – that initiate new signs of identity, and innovative sites of collaboration, and contestation, in the act of defining the idea of society itself. …….~ Homi Bhabha

A boundary is not that at which something stops but, as the Greeks recognized, the boundary is that from which something begins its presencing.…..~ Martin Heidegger

IN 1990, CID CORMAN PUBLISHED the first two volumes of this five-volume magnum opus book of poetry, of. The work was monumental in scope – each volume consisted of 750 pages of poetry. The book included many translations of poetry from around the world and from many different time periods that stretched from the earliest of times – Greek, Hebrew, and Chinese texts – up through contemporary poetry translations. In an unusual move, Corman left his translations un-sourced, that is, he did not attribute his translations to their original authors openly. Some fellow writers, notably Clayton Eshleman, found Cid’s practice suspect and wrote to Cid concerning it. Eshleman explained his dismay in the following way: “I was shocked to find Cid’s translations here, of Homer, Sophocles, Catullus, T’ao Ch’ien, Montale, Villon, Rimbaud, Basho, Malarlarme, Rilke, Ungaretti, Char, Celan, Artaud, and Scotellaro, treated as Corman poems. So I wrote to him questioning such appropriation” (Eshleman).

To do justice to the book, a book of this size and scope, and a book that is the culminating event in the life of a significant American poet, more attention is warranted in exploring the act of his incorporating un-sourced translations into the book – how it was accomplished – and what rationale there may have been for the move, assuming the act is not simply one of appropriation. To understand, appreciate, and comprehend more fully what Corman was up to then, one needs to begin with his poetics, with what informs them – his sense of poetry and its role and place in culture, society and life.

Translation came early to Corman and through the activity – within it – he found himself drawn into a larger community of poetry that would sustain his interest and attention throughout his life. For Corman both the writing of poetry and the translating of poetry developed at about the same time when he was in high school. Here he began translating Greek and Latin poetry. Later, during the war years (World War II), when he stayed home from the war due to his youth and illness, he went deeper into translation. In conversation, some years ago (1994), at his home in Kyoto, he told me about his start in poetry and how intertwined it was with his activities in translation:

…The first quatrain I wrote one Sunday two weeks after Pearl Harbor was… (shakes his head in disapproval)… almost like a translation from ancient Greek, because I had been translating the Agamemnon of Aeschylus at the time. I had studied Greek in high school, and I was very interested still in Greek literature and read quite a bit at University, mostly on my own, this was not for any course. is was just for my own satisfaction. I had read no translation of Aeschylus that struck me as being accurate or true to the thing…. when I started out… I wanted to know about meter. I wanted to understand how poetry was structured, why they used rhyme, the way poetry moved. (Corman, APR 25)

The translation of poetry affects his poetry. Even as a young man, he was able to see the effect that translation was having on his poetry. The force, or influence, is so strong that he seems to recognize a need to disassociate the two: he is unsatisfied with his own poem because it reads too much like the work he has been translating: “. . . almost like a translation from ancient Greek, because I had been translating the Agamemnon of Aeschylus at the time.” The translating of poetry is shaping this poet – the translation work is exerting an influence that Corman recognizes and understands as becoming a part of him. Though he seems to understand the influence can be negative at times, he does not disavow the overall positive influence that the practice is having in teaching him how to become a better poet. In our conversation that day, he went on to make the following points:

By the time I was a sophomore, I was studying Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Mallarmé. And those poets struck me very strongly. They were new to me, and they were different than American poetry. But, I figured by translating I had a way of getting closer to what they were doing, and by doing that, I could learn.

So… it was the beginning for me. So I translated almost all of Les Fleurs du Mal for myself. They weren’t meant for publication. To learn. So it was for me, my education. (Corman, APR 25)

One sees from these comments that Corman understands his beginnings as a poet to be closely associated with his beginnings as a translator. We see also his passionate interest in non-English poetries, and his interest in translating as a means of education, of educating himself as a poet. In looking at the poetry of others, at other poetries, and translating that poetry into his own language, Corman put himself in conversation with other poets, and more importantly found himself within a conversation of sorts that involved poetry – a community of poets that carried him beyond the borders of language, state, and time. In this community, poetry itself became a unifying force –– a center that actually did hold, at least for Cid Corman.

We see further evidence of Corman viewing himself as working within a tradition and within a community when he collects his prose writings and publishes them as one book in two separate volumes. The first volume, Word for Word: Essays on the Arts of Language (Black Sparrow Press, 1978), contains essays related directly to his own poetry and poetic theory. The second volume, At Their Word/Essays on the Arts of Language (Black Sparrow, 1978), concerns itself with translation, and with the work of other writers: “At Their Word.” The two volumes make for a whole; with each volume informing what is said in the companion volume. Corman knows how essential translation has been in helping him to shape and refine his own understanding of poetry and how, in turn, his poetics have informed his translations of other’s poems.

And as it turns out, the first two essays in the second volume take up the topic of translation. Here, in the first essay, Corman offers five translations and commentary upon those translations: “translator’s notes.” The poems he offers are from Rilke, Baudelaire, and Montale. In his prefatory comments at the start of the essay, he offers the following explanation:

The versions here offered (my emphasis) are representative of different approaches possible. In all cases, however, the poems are pieces that have been savored and put into English originally for no other purpose than to prolong the translator’s own pleasure and perhaps to discover some possibility in them for his own tongue. Only where the results seem felicitous poems too (my emphasis) have offerings (my emphasis) been made to a larger audience. (Corman, ATW 10)

Corman’s use of the term “offer,” underscores his sense of giving – or gifting – the translations to the reader with humility – he makes no claim that the translations are definitive. They are offered – the reader can take them, or leave them: “The versions here offered . . .” They are being offered because the original poems were poems that he appreciated so deeply that he was moved to translate them, poems he “savored and put into English to prolong his own pleasure.” His versions of the poems, and only those versions that have become poems in English, and thus deemed worthy of being shared, become “offerings” to a wider audience. Corman’s explanation, particularly his use of the word “offerings,” implies both his giving something of himself to the reader – his work as a translator – and also – and more to the point here – his gratitude for the gift of the original poems. In this gesture and use of the word “offerings,” he implies his awareness of being part of a community that has involved many others over time.

He shows this attitude of gratitude towards the original poets and those who have translated the poem when he speaks of titling one of his translations, in this case the Baudelaire’s poem, “La servante au grand coeur dont vous étiez jalousie.” Unlike other translators who have tried to approach the untitled poem by translating the poem’s first line as the title and coming up with titles such as “The Servant” or the “The Kind-Hearted Servant of Whom You Were Jealous,” Corman titles his translation simply “after Baudelaire.” In his “translator’s notes,” he explains that “’After’ . . . is quite honest, for countless versions over many years achieved this result – which is finally a sort of homage to feeling shared.” The word “homage” as in the case of the word “offering” suggests an awareness on Corman’s part of being involved in a community – a world poetry – and a world that can be shared across time, space, and culture. Here is Corman’s version of Baudelaire’s “La servante au grand coeur dont vous étiez jalousie:”

after Baudelaire

The bighearted nurse

you envied, buried

sod, merits flowers.

The living thankless

rest between warm sheets

while the poor dead feel

all alone, no one

to bring them fresh trash.

If, at the good fire,

I saw her sitting,

some December night

found her in my room

crushed from the long bed

gazing at this child,

what cold worlds tell her

tears filling those eyes?

(Corman ATW 10)

Corman felt a need to translate, as well as a need to share his translations of poetry with others: To make “offerings” to a larger audience. We see further evidence of this in the story of his coming to translate the poetry of Paul Celan and to publish that poetry in his magazine Origin.

After leaving the University of Michigan, and after a few years back in Boston where he hosted a weekly poetry radio program, Corman was awarded a Fulbright and traveled to France to study at the Sorbonne. In Paris, Cid wrote poetry and immersed himself in translation. During this time, in 1955, he met the poet Paul Celan, virtually unknown in North America at the time, and began translating his work into English. Some years later, when Corman wanted to publish his Celan translations in his magazine Origin, he contacted Celan to ask permission. Celan refused to give permission and threatened litigation against Corman if he pursued publication. After some consideration, Corman went ahead and published the poems in Origin and, as promised, Celan wrote an angry letter to Corman threatening “persecution” – an ironic typographical error, as Corman would later remark to me, considering Celan’s persecution by the Nazi’s during the Second World War. Celan had meant to write “prosecution,” of course.

In 1994, when I asked Corman how he first meet Paul Celan, he told me the following story:

My friend. I was living with her at the time: 1955, in Paris. Edith Aron (German, but reared mostly in Argentina, of Jewish descent too) who had helped Paul Celan get a job with UNESCO introduced me personally to him one day. He seemed very dour to me and they did most of the talking. Both near my age – early 30s. And she gave me his first two books and suggested we translate from them together. We did. And I did the first English versions ever and a few were published in Toronto by Ray Souster at once. I didn’t like those first two volumes as much as what followed. And I bought each of his books as they occurred thereafter and translated each – with someone native to German assisting. I met him just as he was really coming into his own. And I have translated all his work – much of it still unpublished.

I asked Corman what specifically attracted him to Celan’s work, and he answered in the following way:

His depth of language use – not as technics (cf. Zukofsky) but as the only way to get language to tell what life humanly is – touched me. I couldn’t /wouldn’t be as obscure and “difficult” as he allowed himself/his language to be, but I could feel the truth of what he was doing, or trying to do. And that moved me. To want to share that work – despite his challenging me. (Corman, APR 26)

Corman speaks in terms of feeling “moved” to translate the work, feeling compelled to share the work of Celan with others. He decided to publish the translations despite Celan’s “challenging” him. His rationale being, in so many words, that he felt compelled to share it – that he could feel “the truth” of what (Celan) was doing: “His depth of language use . . . as the only way to get language to tell what life humanly is – touched me.”

One might find fault with Corman’s rationale as stated here. Is his desire to share the work reason enough to publish his translations without Celan’s permission? But in questioning Corman rationale, one would also do well to consider Corman’s passion and sincerity to share the work. Every- thing about Corman’s life in poetry suggests that his reply to Celan was sincere. Of course, I do not mean to assert that passion and sincerity, in and of themselves, make Corman’s actions right or absolve him of honoring the wishes of Celan. What I do want to point out is that Corman was deeply motivated to act in the way that he did act, and that his action speaks to his understanding of poetry in the world, and per- haps also to questions of ownership of it.

Corman felt Celan’s work should be shared – that it needed to be shared. This desire to share poetry has remained consistent throughout Corman’s life: his poetry radio program in Boston was a way for him to share poetry with a wider community. It was a way of creating a community around poetry, for poetry. His founding of the magazine Origin was another way in which he worked to share poetry with a larger community: he wanted to get poetry into the world, particularly the kind of poetry that mainstream poetry magazines were not taking seriously, at least not taking seriously enough to publish.

Written correspondence was a further way in which Corman shared poetry with others. Correspondence, i.e. letter writing, was a central part of his life as a poet. In conversation once, he referred to it as his “life-line.” When I asked him if there was anything that stood out in the letters that he received – anything remarkable? He told me, “Everything. Every letter is my news. Is poetry” (Corman APR 26). At the time, I didn’t think he meant that the letters were themselves really poetry – but over the years I have come to doubt that first understanding – maybe he did mean it, literally. After all a letter, like poetry, involves the experience of one person sharing news, to use Pound’s word for poetry – news that stays news – with another. Letters and poetry are correspondences, if you will, that share an experiential quality about them: the words of the writer being shared with the reader in an intimate way. So for Corman, this idea, of letters being “poetry,” is not as far fetched as it might at first sound. Perhaps his feeling on this accounts for his publishing letters right alongside poetry in his magazine Origin. In the first series of Origin (1951-1957) Volume XIV/Autumn, for example, he published the following section of letter by the Canadian poet Irving Layton:

Letter to Cid Corman

Lac Desert, County Lab

Quebec

August 5, 1954

Dear Cid,…

In all these poems I’ve tried to express the idea “in the image,” for although as a rule I leave theorizing about poetry to others, there are one or two work-a-day rules I try to govern myself by when writing verse. For me, rhythm and imagery usually tell the story; I’m not much interested in any poet’s ideas unless he can make them dance for me, that is embody them in a rhythmic pattern of visual images, which is only another way of saying the same thing in different words. If I want sociology, economics, uplift, or metaphysics; or that generalized state of despairing benevolence concerning the prospects of the human race which seems to characterize much of present-day poetic effort, I know my way around a library as well as the next man. Catalogues are no mystery to me. I regard the writing of verse as a serious craft, the most serious there is, demanding from a man everything he’s got. Moreover, it’s a craft in which good intentions count for nil. It’s how much a man has absorbed into his being that counts, how he opens up continuously to experience, and then with talent and luck communicates to others (my emphasis) without fuss or fanfare or affectation, but sincerely, honestly, simply …

Yours, Irving

This letter appeared in Origin alongside Layton’s poems. It was not set off as a prefatory statement of any kind but appeared on the page as if a poem, in the flow of the poems presented there, with several poems preceding it and several poems following it.

Poetry is a craft, according to Layton, that demands much of the poet: “demanding from a man everything he’s got.” It is also a craft that demands the poet open up “continuously to experience,” a craft that calls upon the poet to communicate to others “without fuss or fanfare or affectation, but sincerely, honestly, simply . . .” These ideas are all in sympathy with Corman’s own poetics, as editor and as poet. Certainly, an open- ness to experience, and a direct form of communication/address are characteristic of Corman’s poetry. Here, Layton’s letter may be seen to be a poem in Corman’s eyes in so far as it achieves a rhythmic liveliness in its prose while communicating in a direct, unaffected and sincere way. A piece of writing that opens up to experience and communicates with others. In publishing the letter, we see Corman, the publisher, opening up to the experience of the letter and sharing that experience with others. In placing poes and letters in the magazine in such away, Corman seems to ask, “Why can’t a letter such as this be read as a poem?” Corman opens himself to the possibility of the letter being read in such a way – opens himself to that experience. In publishing the letter, Corman participates then in a reciprocal gesture of gift giving, and communicating with others – he shares Layton’s letter with a wider audience.

Corman’s active life as a correspondent is legendary, and the books of correspondence that have been published over the years indicate this – no doubt more books will follow. The many letters between Corman and Charles Olson, for example, were edited and published in 1987 and in 1991 (Charles Olson & Cid Corman, Complete Correspondence 1950 –1964 Volume 1 and Volume II. Ed. George Evans, National Poetry Foundation, University of Maine Press); Olson’s letters to Corman were published earlier in 1970 (Charles Olson, Letters for Origin, Cape Goliard [London] and Grossman [New York] Ed. Albert Glover); a collection of Lorine Niedecker’s letters to Corman was published in 1986 (Between Your House and Mine: The Letters of Lorine Niedecker to Cid Corman, 1960 – 1970, Ed. Lisa Pater Faranda, Duke University Press); a more recent volume of Corman Letters was published in 2000 (Where to Begin, Selected Letters between Cid Corman and Mike Doyle, Ed. Keegan Doyle. Ekstasis Editions).

The contemporary American poet and translator, Andrew Schelling provides a telling and instructive story of his coming into correspondence with Corman through the aegis of Clayton Eshleman, who had known Corman in Kyoto years earlier and knew first-hand of his approachability, and his willingness to help younger poets. As Schelling recalls in a tribute that he wrote after Corman’s passing in 2004, he was a “fledgling poet . . . just beginning to publish . . . in the early to mid eighties” when he first corresponded with Cid Corman. Clayton Eshleman told him he had “to get in touch with Cid Corman.” Eshleman’s suggestion was a piece of “true counsel,” and not simply “a piece of advice.” Schelling listened to Eshelman and contacted Corman and they began corresponding. In short order, Schelling and Corman became correspondents. Corman replied “to every letter instantly,” Schelling says, expressing wonder at Corman’s generosity and attentiveness: “his aerograms usually leaving the day my own had arrived. Always an aerogram, always every patch of space on it filled with typewritten words—almost always a small poem or two or three typed onto the outside.” (Schelling)

As a poet living far from the American scene, one might expect Corman to have less to offer Schelling than an elder poet based in the U.S. and familiar with contemporary American poetics. Schelling however did not find this to be the case. While it was true, Schelling concedes, that Corman was not always up to date on the latest developments on the American scene, and that poetry news reached him “in curiously winnowed ways,” Schelling felt that Corman had something special to offer. According to Schelling, Corman’s “expatriate status gave him an in-touch status hard to qualify but completely visible to all who knew him. He was more a citizen of the world than are most American poets. His correspondence permitted him equal access to friends in Japan, Australia, Germany, Canada, and Mexico.” Corman was in his own curious way at the center of things – his correspondence had him in touch with poets around the world. For a young poet like Schelling, a poet interested in translation, Corman’s international contacts and his active engagement with translation had much to offer Schelling.

Corman wrote tens of thousands of letters to contacts around the world during his lifetime. His correspondents included friends, family members, and poets, as well as politicians, philosophers, artists, and religious figures. His correspondence with others was something that he wanted to share, that is, he wanted not only to connect with others through correspondence, but he wanted to connect others to others through correspondence. If he thought that one of his correspondents would benefit from getting to know another of his correspondents, he would try to put them in touch with one another. Through his correspondence then, Corman tried to introduce different writers to each another. When I first began corresponding with Corman on a regular basis, he frequently went out of his way to send me contact information about writers he thought I should connect with.

When one looks at the sum of Corman’s life then, one feels convinced that Corman felt poetry was, in large measure, about sharing and community. He felt that one of the most fundamental qualities of poetry was found in its ability to bring two individual lives together – to create a community of two: a conversation between the reader and the poet. This sentiment is found throughout his oeuvre. Here are four poems that demonstrate some of this:

Poetry becomes

that conversation we could

not otherwise have.

(Corman, ND 86)

Assistant

As long as you are here –

Would you turn the page?

(Corman, APR 23)

The Call

Life is poetry

and poetry is life — O

awaken — people!

(Corman, APR 21)

There’s only

one poem:

this is it.

(Corman, ND 121)

In elegant and conversational language, Corman asserts the primacy of poetry in human relations in these poems: “Poetry becomes / that conversation we would / not other- wise have.” Poetry is unique and solitary in what it offers – nothing else is quite like it.

In the second poem we see a humorous and yet quite serious invitation for the reader to participate actively in the reading of the book. It is as though Corman himself were reaching out through the poem to make contact with the reader and participate in the reading of the book: “Would you mind turning the page?” The poet shows up and speaks directly to the reader – let’s the reader know that he, the poet, has thought of him. The poet has envisioned the reader one day finding himself on the page and reading. This is the community that Corman values – the interaction of one person conversing with another through the medium of poetry. Corman moves through time and space in doing this, he is aware of the poem’s ability to transcend time and space and remain relevant – to still speak. Here he quietly alludes to times’ passing and to the ephemeral nature of life: “As long as you are here.” This conversational line, a line we commonly hear, is brought to bear its full measure of import within the poem: the weight of intonation and stress falls precisely on the word “are:” “As long as you are (my emphasis) here.” If Corman were not the poet that he is, he might have written “you’re” instead of “you are.” Corman wants the reader to sound “are:” “As long as you are . . .” In other words, as long as you are here, and alive, will you turn the page?

This subtle gesture points to one of the enduring qualities and strengths of poetry: the poem speaks to the reader even when the poet is gone. It speaks to the movement of time, the movement within a lifetime, to the human condition of being here now and knowing we will not always be. The poet after all, is not really with the reader on the page in the present moment of reading. He has passed on. The reader in reading the poem understands this, feels it through the poem.

The final two poems cited above get at similar notions as the first two poems. “The Call,” again announces the primacy of poetry, equating it with life itself: “Life is poetry/and poetry is life – O.” And the final poem makes the playful and, at first glance, seemingly audacious statement, that “There’s only/one poem:/this is it.”

Of course, in a real sense, Corman means exactly what he says, and that is, that the impulse behind the writing of a poem, the engine of the poem, the origin of any poem, of all poems, is the same at its source – it is the impulse to speak, it is the “O” of breath and being – the reaching out of one to another through language – the poet and reader together – the song that brings one to another. It is at base a connectivity, and communication, a form of communion, or community: ”the conversation/we could not otherwise have.” Seen in this light, we understand the claim that the poem makes: there is one poem and it resides in our very breathing and breath. It is life.

This poem, this last one, is an especially helpful poem to consider in relation to Corman’s book of and his questionable act of incorporating un-sourced translations into the book alongside his own poems. I say this because in this poem, we see a clear statement which may be seen as supporting what Corman has done in the book; that is to say, he makes his poems and his translations one book, one unified book, one poem: “There is /only one poem:/ this is it.”

***

Of is, at first glance, a strange title for a book. How many books can one think of that contain a preposition for a title? Strange as it is, it is a title that is precise and telling, and one meant to draw attention. When one opens the book, one finds a preface that immediately addresses the rationale behind the titling of the book:

for those who find themselves here

and sounding the words care to be

this is a book of a life as exacting as any

other, not in chronological order, but

through as for all time: a small proportion of

what has occurred to me and to which the work

unseen is complementary

the title reflects a precisely physical metaphysics:

the meta the indissoluble unfathomable fact: the

genitive case: to which we are all beholden and

within which we remain hopelessly particular

and to the extent that a poetry can, these poems

articulate it – which humbly (meaning – aware

of there being no choice) reveals transparently,

whatever else may be felt, I trust (trust implying

you), wonder, gratitude, pain, and love.

(Corman, of Vol. I, 2)

The Preface begins by immediately engaging the reader: “for those who find themselves here/and sounding the words care to be.” The reader is said to be “sounding” the words, suggesting that the reader is actively involved in both sounding the depth of the words – the depth of their various and associative meanings – as well as physically making the sound of the words in their mouths – “sounding” them. The words themselves are said to be things that “care to be,” underscoring Corman’s emphasis on our appreciating “words” as having an existence beyond the individual’s control – emphasizing, reminding the reader that words exist independent of the individual speaker – that they are thus shared within a larger community. If words did not possess this characteristic capacity, of what use would they be? To the extent that words are shared, they carry meaning and significance for us, and they bring us together, allow us to communicate with each other. Readers can “find themselves here” (my emphasis) precisely because the words on the page belong to the reader as much as they belong to the writer.

As Corman says, “The title reflects a precisely physical metaphysics,” that is, it attempts to underscore the existent relationship between the individual and the world beyond the individual to which the individual is both separate from and a part of: “the genitive case: to which we are all beholden and/within which we remain hopelessly particular.” Language is thus the bridge, or the “connectivity,” as the post-colonial scholar Inderpal Grewal refers to it (Grewal 236).

Corman continues to elaborate upon this theme on the following page of the book with another epigraph. Here he translates the Greek of Philo of Alexandria (20 B. C. E. ~ 50 C. E.). It is salient to note that Philo himself was writing a literary work in Greek that was based on the older Hebraic writings of the Bible (Genesis), namely the Old Testament. Thus Philo too, like Corman, was involved in translation – the crossing of linguistic borders. Corman translates the epigraph as follows:

The soul of the most perfect is fed by the word as a whole; we may well be content should we be fed even by a portion of it.

PHILO: Allegorical Interpretations of Genesis. III, Ixi, 176.(Corman, of, Vol. I. 1)

In this epigraph, Corman once more alludes to there being a whole to which we belong: “the word as a whole.” With my layman’s knowledge of ancient texts, I cautiously interpret Philo in the following way: I take the “most perfect” as referring to God. Following upon this, I understand God is fed “by the word as a whole.” I read “the word as a whole” to refer to the whole of humanity, and that humanity’s offering God prayers, songs, poetry – praise feeds God. If the word as a whole is what God – “the soul of the most perfect” – is nourished by then we lesser ones might be sustain by, and should be “content” with, even a portion of it, the word: our own individual languages. The divine world and the human world are bound by, and through, the word. For Corman then, poetry is nothing less than manna – an essential thing – meant to be shared. Further, it is the diversity of languages that Corman is signaling as being of importance. It is not one particular language but the word as a whole – all poetries contributing to the whole that feeds the most perfect.

With this title, preface, and epigraph, Corman makes the case, rhetorically, for including un-sourced translations from many different languages and time periods into the book. His gesture is to say that we are OF this material – that the poetry of the world belongs to all of us. Moreover, he means to suggest that we are shaped by our inheritance of these languages, poetries, and cultures. We are of them – born into a scene and situation that we did not ourselves wholly create. He honors the inheritance.

In 2000, Corman responded to the charge of appropriation – whether or not his use of un-sourced translations in of was a form of appropriation. Did he deliberately leave the names of the original authors of his translations off the page? In his characteristically frank way, he acknowledged that he had done so while emphasizing that he did so with a purpose:

Yes, of course. Take Eshleman, who I know very – have known very well: very angry at me for doing that, not to give the credits. But anyone who’s really interested could easily recognize… Most of them are very famous pieces; the others, often the title gives it away, where the source is. Anyone who’s really interested could easily find out. But the point is precisely I don’t want the names introduced. My dream, even when I first began, the first year I wrote poetry, was to be anonymous; and if you look at my books that I myself designed without fail, my name is not on the title page. This is unique: there’s nobody else that ever has done this and I do it deliberately. My name is put as a signature at the end, but actually, I would rather have my name not in the book at all…

(Corman, ICPR 1)

“But the point is precisely I don’t want the names introduced.” Corman doesn’t want the names introduced because he wants the work, of, to be that whole that he alludes to in the epigraphs. His own poems will be part of the book, but they will find themselves within a community of poetry – his poems will be at home within a greater whole.

While I think it is understandable how the charge of appropriation could be leveled at Corman – for he does incorporate translations of others’ poems into his book – I believe under close analysis the assertion of appropriation does not stand up. “Appropriation” doesn’t adequately come to terms with the nuanced complexity of Corman’s gesture, and it is in the nuance and carefully balanced aesthetic manner in which the translations are brought into relationship with Corman’s own poetry that matters. The manner in which the translations are incorporated allows for them to be felt as translations, known as such, while not overtly crediting them as translations nor naming the authors.

Corman asserts in the interview that anyone really interested in finding out the source of a poem can easily do so because the poems are well known, or they are tagged in a way that allows them to be identified: “But anyone who’s really interested could easily recognize . . . Most of them are very famous pieces; the others, often the title gives it away, where the source is.” In other words, Corman maintains that the translated poems remain in some fashion distinct and particular, in some way known and sourced.

This is in keeping with what he announces in the Preface and through his use of epigraphs. In some measure, “a precisely physical metaphysics” is enacted in the book: the translated poems remain particular within a constellation of other poems, including Corman’s own. The ability of Corman to translate poems and incorporate them so that they become both distinct and a part of the whole is one of the signal achievements of the text. And in so much as readers experience the poems as translations within the book, that is, poems different from Corman’s own poems, a multitude of voices are allowed to enter the book and circulate through and between Corman’s own poems.

For Corman to insert the names of the original authors on every page where a translation appeared would be to break (brake) the resonant play of the poems echoing off each other. It would be, in short, contrary to the aesthetic intentions suggested in the titling of the book. This is to say that the listing of sources would break the text into discrete parts and detract from the whole that Corman is trying to create.

When readers encounter translations in the text, the readers should understand that the poetry is other than Cor- man’s own. When Corman’s friend and fellow poet, Clayton Eshleman read the book, he had precisely this experience – he recognized certain poems as translations despite their lack of citation. The first poem, for example, is entitled Shingyo; as such, it immediately signals a foreign language – in this case Japanese. The poem is actually a translation of an ancient prayer, a sutra that comes from India. Just as Philo’s use of the Genesis story demonstrates his awareness of precedent, Corman too chooses a work that demonstrates his awareness of precedent, and the way in which languages and ideas cross borders and are shared among and within communities. The sutra, which is well known in Asia and in- creasing in the West, was written in Sanskrit at around 350 C. E. Later, Buddhist monks brought the sutra to China where it was translated into Chinese. Then the Japanese brought the sutra to Japan, and translated it into Japanese. Here, the sutra, known in English as “The Heart Sutra” is a work that has passed over and through many national borders, languages, and cultures to be shared anew through further translations. Interesting to note, and apropos to what Corman has said about his own wish for anonymity in poetry, the poem he begins the book with – his magnum opus – is an anonymous work, a poem that has been chanted by many different people of various cultural backgrounds for ages.

Beginning the book with this poem amplifies the theme struck by the epigraphs and the Preface, that is to say, the poem moves us to confront the paradox that we find ourselves in – we are particular and yet each exists within a community – in relationship with others – our shared language tells us as much: no one person invented the language, and no one owns it. It is shared. Shingyo speaks to a condition of enlightenment, which would have us acknowledge being both a part and a whole, a poem that celebrates non-duality:

SHINGYO

Seeing reflecting sense nonsense

Friend – here is emptiness here is form

Unborn undying – untainted

unpure – no more no less – therefore

Friend – nothing to know or not to

to come to this – the suffering

reaching where it is and is not

Come – body – and go – body – no

body – gone to the other – gone.

(Corman, of, Vol. 1. 5)

The poem speaks to a sensibility that is unified, a non- dualistic sensibility – one that recognizes both the part (“body”) and the whole (“gone to the other”). It reaches through both – goes beyond opposites – to locate a site of commonality in a singular word of compassion “Friend.”

It is not only by titling the poems carefully then, as in the case of “Shingyo,” and by including well-known translations that Corman indicates which poems are translations: Corman also employs other techniques that quietly signal translation. The entire first section of the second volume of the book, for example, is indexed in the back under the title “Offered,” echoing the title of the book, of. Indexing the poems in this way, suggests that the majority of the poems in the section are translations, as they indeed are.

And it is not only by his unobtrusively marking the poems as translations that Corman succeeds in building the polyphonic quality of the text; He also succeeds through skillful translation. Corman is careful to honor the text, to honor the rhetoricity of the original. This is to say that his translations are distinguished by what the post colonial scholar Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak refers to as “fraying,” a manner of translating that eschews the long searched-for equivalency between the original and the target language in favor of acknowledging qualities of the original that may be better left un-translated, giving the text a frayed or roughened feel. As Spivak puts it, “The task of the translator is to facilitate love between the original and its shadow, a love that permits fraying, holds the agency of the translator and the demands of her imagined or actual audience at bay.”

Corman’s translations leave the text open and rough with possibility. When balanced between the translator’s agency and the reader’s expectation, Corman honors the rhetoricity of the text. In 1964, long before the term of fraying came into use in translation studies, Corman spoke about his willingness to retain Japanese words in his translations. For example, in the Preface to his translation of Basho’s Oku-No-Hosomichi, (Back Roads to Far Towns, Munjinsha 1964) he and his fellow translator decided to retain original Japanese words in the translation. Corman expressed their decision this way:

If the translators have often not accepted Western approximations for particular Japanese and/or Chinese terms, it is not to create undue difficulties for readers, but rather to admit an exactitude otherwise impossible. As a result, notes may be needed in greater profusion than before. (Basho, BRFT 10)

Corman is not going to smooth the text out so that it reads comfortably in English if that means compromising too much of the complexity of the original. The original words, rich in associative meanings, may offer a complexity that the English words cannot adequately represent, that is, the English equivalent is not accurate enough. This decision on the part of translators (Corman and Kamaike Susumu), make it is necessary for them to use original Japanese words in the translation. In translating Basho’s Oku-no-Hosomichi, Corman and Kamaike retain original Japanese words in both the prose and the poetry. Here is some of their translation work – the poetry following the prose:

Afterwards off to the Sesshoseki on horse sent by

the kandai. Man leading it by halter asked for a

tanzaku. Beautiful he wanted one:

across the meadow

horse take your lead now from the

hototogisu

(Basho BRFT 25)

In this brief passage, Corman and Kamaike retain four Japanese words. Their notes in the back of the book relate the following:

kandai: Castle overseer

Sesshoseki: Still exists, though fenced about. The legends associated with it are told in Noh of the same name.

tanzaku: Narrow strip of fine paper to write poetry on; a poem

hototogisu: Japanese cuckoo, whose name is its song.

(Basho BRFT 122)

In using original words the translators intend “to admit an exactitude otherwise impossible.” They bring the Japanese flavor of the original in – they “admit” it – because English does not have similar words that are reliably precise. By retaining the Japanese words the translators allow the shadow of the original to be felt and appreciated. By “shadow” I mean to suggest that Corman and Kamaike’s translation emphasizes that while it is not the original it does retain some of the original’s defining qualities. Hototogisu, for example, is the Japanese cuckoo, but more to the point – and the point Corman and Kamaike want the reader to experience – is the fact that the name of the bird IS the bird’s song. When the reader reads “hototogisu” the reader hears what the Japanese themselves believe the bird sounds like when it calls. And it just so happens that this has a further meaning (or possibility of meaning) – the sound of the song is imaginatively thought to be the sound of a Buddhist sutra. Thus, the bird is thought to be, figuratively speaking, chanting a sutra. The bird and its call are steeped in the folklore of Japan, and its literary history and culture. The reader gets the onomatopoetic sound that the Japanese themselves feel best represents the sound of the bird. The reader is thus connected in this way with Japan: its animals, culture, language, and people.

Corman frays many of his translated texts in of in similar ways. When he translates Catullus, for example, he uses the Latin title of the poem and translates the poem in the following way:

IUCUNDUM, MEA VITA

Happy, my life, to me you propose love

This ours between us perpetual be.

Great gods, see that she really can promise

And she say so honestly and from heart,

So that it be ours all life to continue

Eternal this trust of blest affection.

I will tell you the secret.

(Corman, of, Vol. II, 30)

Encountering a poem such as this would lead any observant reader to conclude that she is indeed reading a translation. Why else would the poem be titled in Latin? If this doesn’t wake the reader to the fact of the poem being a translation, the reader could Google the title and find the poem ascribed to Catullus. In other worlds, the poem calls out to be understood – read – as a translation. The fraying one finds in the translation makes this even more abundantly clear. This translation is not rendered in Corman’s contemporary American English, but in a distinctively textured, tonal, and syntactical manner quite foreign to it, resulting in a poem that sounds ancient. Some of the ancient sounding qualities of the translation come from Corman’s mining the possibilities of the original Latin poem. Corman draws our attention to the word “ours:” “Happy, my life, to me you propose love/this ours between us perpetual be.” Here, “ours” functions as a noun and retains its Latin sense of something not only as something shared between people but something alive and living, and “ours” that is, “perpetually to be, a love that comes “honestly” and “from heart.” The word “ours” is struck again in the penultimate line with stress and weight – “So that it be ours all life to continue.”

Beyond the polyphonic and the symphonic qualities that the book achieves by bringing in such a rich variety of voices from various cultures, languages, and time periods, Corman’s book, of, reminds us that we come from this stuff – from this poetry – and that our languages and poetries have played a role in shaping the world we live in – the way in which we see and understand ourselves and the world.

Homi K. Bhabha, the literary scholar and cultural theorist, in commenting upon the contemporary Mexican American musical artist Guillermo Gomex-Pena, who travels between Mexico and American to sing songs on both sides of the border, both old and new songs – a man who sings to different audiences – Spanish-speaking audiences and English-speaking audiences, may provide us with the clearest lens yet by which to discern and appreciate what Corman achieves in his own crossing of boundaries – the boundaries of time, space, languages, cultures, and poetries – not to mention his crossing back and forth between his own poems and his translations.

According to Bhabha, Gomez-Pena’s actions of performing songs in both languages on both sides of the Mexican and U.S. border – songs that are traditional as well as new – creates a generative “inbetween space” that allows for the artist to elaborate “strategies of selfhood – singular or communal – that initiate new signs of identity . . .” This “inbetween space,” he asserts, is a site of “collaboration, and contestation.” (Bhabha LC 336) Corman’s work too creates such an inbetween space. It also creates a site of collaboration and contestation in so far as we see him collaborating with other poets through the act of translation, taking their poems and translating them into English. We can see the contestation in terms of his own voice, his poems, asserting themselves through the surrounding poems, many voices vying, if you will, to be heard.

In fact, Bhabha prefaces the above comments by saying that what is “theoretically innovative and politically crucial is the need to think beyond narratives of “originary and initial subjectivities and to focus on those moments or processes that are produced in the articulation of cultural differences.” It is precisely this activity that opens up what he terms “the inbetween space which leads to new signs of identity . . . in the act of defining society itself:”

What is theoretically innovative, and politically crucial, is the need to think beyond narratives of originary and initial subjectivities and to focus on those moments or processes that are produced in the articulation of cultural differences. These ‘inbetween’ spaces provide the terrain for elaborating strategies of sellfood – singular or communal – that initiate new signs of identity, and innovative sites of collaboration, and contestation, in the act of defining the idea of society itself.” (Bhabha, LC 337)

Corman’s inclusion of poems from many languages – translations – poems both old and new – creates an “inbetween space” that is at once familiar and de-familiarizing – Corman’s own poems written in vernacular contemporary American English sound familiar to the American ear, whereas the translations, such as a poem like “Shingyo,” sound much less familiar because they are sourced in different languages, time periods, or cultures and because Corman’s renderings in English of those translations tend to be deliberately marked or frayed, creating a degree of dissonance between his own poetry and the translated poetry. In this way, Corman creates a gap, a space, and in-between, that allows, admits, a larger world of poetry to enter. He gets beyond, as Bhabha would have us do, “originaries and initial subjectivities” and allows the reader to experience a larger world of poetry by allowing her “to focus on moments or processes that are produced in the articulation of cultural differences.” It is through this performance, this act, that Corman succeeds in initiating “new signs of identity,”which would lead to “the act of defining the idea of society itself ” (337).

The new identity that Corman wants us to embrace says that WE are OF this stuff, this material, this poetry. It is an identity that includes others – other languages, other poetries, other stories, and it accepts them graciously and identifies with them as human stories, familial stories. The new identity implies that the poetry of the world is gifted – offered – in the way that language itself is gifted to each of us, that is, handed down to us by our mothers and fathers, freely given. Corman’s move is deliberate and provocative – an insurgent act – and we should understand it as such and appreciate it as such. Rather than apologize or become defensive in responding to Eshleman’s question regarding appropriation, he becomes more assertive: “. . . the point is precisely I don’t want the names introduced. My dream, even when I first began, the first year I wrote poetry, was to be anonymous” (Corman, ICPR).

In placing translation directly beside his own poems, Corman forces us to ask questions about poetry and poetry’s role and place in the world at a time when cultures and languages are crossing borders more rapidly than ever before. He asks us if we are ready to hear what a world of poetry has to tell each of us about the nature of our existence on the planet. Do we understand the generous loving gesture that the poem itself is offering each of us? Can we approach not only poetry but each other with a larger sense of gratitude, or, as he would say in another poem, can we listen to the poem and each other?

Listen.

What is it – you ask?

I keep telling you:

Listen.

(Corman, ND 64)

Corman wants us to understand that poetry is as important now as it’s ever been in helping us through the night in helping us understand who we are, and what we are – even if poetry is nothing but cry in the night, even if it’s simply one person reaching out to another. Corman is not concerned with copyright issues, or questions of appropriation. It is as though he deliberately pushes these concerns aside in order to get at something more elemental and vital, and that is to remind us that poetry bring us together into a conversation – that language itself comes before ownership, that it is held in trust and commonly constructed. What ever it is that compels a person to write a poem, or for a person to read a poem, gestures toward shared community.

Corman’s magnum opus, of, by combining both translations from other poetries and placing them beside his own poems in a single book allows us to think beyond boundaries into new spaces that allow for a world of poetry to open up, a large world we find ourselves a part of. In doing this, the book reminds us that poetry, to be worthy of the name, to remain vital in our lives, must remain within the community as something offered and shared.

Family

We know it is love

Because we are – as

The stars are – because

Dante and Shakespeare

And Homer were and

So many others

Who never leave us

Alone – light shining

Under the closed door.

(Corman, of Vol. II 378)

—Gregory Dunne

§

Works Cited

Bhabha, Homi K. “Locations of Culture.” The Transnational Studies Reader: Interdisciplinary Intersections and Innovations. Ed. Peggy Levitt. New York: Routledge, 2007. 233-237. (Print)

Corman, Cid. At Their Word: Essays on the Arts of Language. Vol. 2. Santa Barbara, California. Black Sparrow. 1978. (Print)

Corman, Cid. Back Roads to Far Towns. Buffalo, New York: White Pine Press. 2004. (Print)

Corman, Cid. “Cid Corman in Conversation.” Interview with Philip Rowland. Flash Point Magazine, 16 Sept. 2000. (Web) 06 May 2013. <http://www.flashpoint mag.com/corman1.htm>.

Corman, Cid. Interview. “An Interview with Gregory Dunne. “American Poetry Review. (July/August 2000): 25. (Print) Corman, Cid, Mike Doyle, and Kegan Doyle. Where to Begin: Selected Letters of Cid Corman and Mike Doyle, 1967-1970. Victoria, B.C.: Ekstasis Editions, 2000. (Print) Corman, Cid. Nothing Doing. New York: New Directions,

- (Print) Corman, Cid. of. Vol. 1 and 2. Venice, California: Lapis. 1990.

(Print) Corman, Cid. The Gist of Origin, 1951-1971: An Anthology.

New York: Grossman, 1975. (Print) Dunne, Gregory. “Getting the Secret Out of Cid Corman.” Poetry East: 44 (Spring 1997): 9 – 23. (Print) Eshleman, Clayton. “Cid,” Cipher Journal. 12 June 2004. <http://www.cipherjournal.com/html/eshleman_cid_ii.

html> (Web) Grewal, Inderpal. Transnational America. Durham and London: Duke. 2005. (Print)

Heidegger. Martin. Poetry, Language, Thought. Trans. Albert Hofstadter. Harper Colophon Books, New York:1971.

(Print) Niedecker, Lorine, Cid Corman, and Lisa Pater Faranda. “Between Your House and Mine”: The Letters of Lorine Niedecker to Cid Corman, 1960 to 1970. Durham [N.C.: Duke UP, 1986. (Print)

Olson, Charles, Cid Corman, and George Evans. Charles Olson & Cid Corman: Complete Correspondence 1950- 1964. Orono, Me.: National Poetry Foundation, Univer- sity of Maine, 1987. (Print)

Schelling, Andrew. “Schelling CC Death Notes.” Web log post. Schelling CC Death Notes. Cipherjournal, 28 Mar. 2004. (Web) 03 May 2013.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “The Politics of Translation.” Destabilizing Theory. Eds. Michele Barrett and Anne Phillips. London: Polity Press, 1982. (Print)

.

Gregory Dunne is the author of two collections of poetry: Home Test (Adastra Press, 2009) and Fistful of Lotus (a handmade book by Canadian printmaker Elizabeth Forrest, 2000). He has contributed to Strangest of Theaters: Poets Writing Across Borders (McSweeneys and the Poetry Foundation, 2013). His poetry and prose have appeared in numerous magazines, including the American Poetry Review, Manoa, Poetry East, and Kyoto Journal. He lives in Japan and teaches in the Faculty of Comparative Culture at Miyazaki International College. Quiet Accomplishment: Remembering Cid Corman was published by Ekstasis Press in 2014.

.

.

Detail from Champlain map, Nova Scotia, Bay of Fundy, etc.

Detail from Champlain map, Nova Scotia, Bay of Fundy, etc. Detail from Champlain map

Detail from Champlain map Detail from Champlain map

Detail from Champlain map Champlain map detail

Champlain map detail

Translator David Need

Translator David Need