Anna Maria Johnson

Anna Maria Johnson

Virginia Woolf, in her diaries, once said that she didn’t know how anyone could read without a pencil in his hands; Anna Maria Johnson doesn’t just use a pencil, she uses lines, paint, a self-created concordance and icons to mark the patterns when she is reading. Johnson is an artist-writer-reader who has an uncanny instinct for making visual and synchronic what in a text seems abstract and sequential. After she is done with a paragraph, a page, a sequence of pages, you suddenly SEE the text come alive as a trembling matrix of vectors, internal references, and visual rhythms; reading, Anna Maria Johnson, renders text into a startling work of visual art. This is a wonderful ability and not just a parlor trick; reading for pattern is a key element in understanding authorial intention. Repetition is the heart of art. Too many readers skim a work once and never get to appreciate the tactile, erotic quality of great prose, the physical impulses of tension, insistence and resolution that form its inner structure. Anna Maria Johnson’s “reading” of Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek is a delightful and astonishing work of hybrid art in itself, but it’s also a terrific lesson in HOW TO READ.

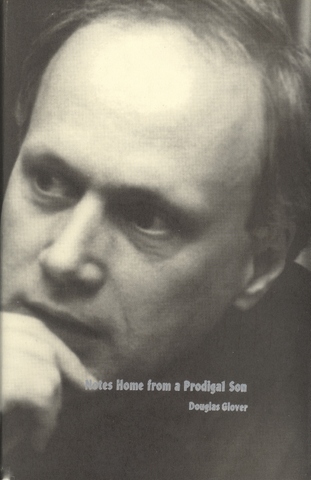

dg

/

Anna Maria Johnson’s altered epigraph page of Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

I. Introduction

EVERY STORY HAS its own circulatory system, with arteries and blood vessels networked and pumping life and nutrients from its heart to every other part. Each book is a watershed, a system of rivers, creeks and underground currents that flow unceasingly, pulled by some kind of unseen gravitational force. A book is a woven web, with silken strands connecting segment to segment.

It’s easy to wonder, while reading an admired author’s flowing narrative, just how she managed to do it. A prize-winning book seems to have been a miracle, a creative rush of genius that burst forth while the writer simply sat and transcribed the words onto the page. But generally, good writing comes down to slow craftsmanship and long periods revising. I find that syntactical patterns and repeated imagery play a dominant role in creating unity and structure, as seen in Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, a book that hangs together through such patterns.

But how, exactly? To find out, I re-read Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. I focused on sentence structure and image patterns, for it is syntax (specifically, repetition, parallel structures, and lyricism), in combination with image patterns (concrete images that recur throughout a given work), which gives unity and movement, or “flow,” to this book. According to Mary Stein, “a sophisticated use of syntax in prose can function well beyond lyric or ornamentation.” Syntax can be used as metaphor, she adds, in order to “motivate narrative movement and provide story structure.” [1] I would add that “syntax as metaphor” sometimes takes the form of image patterns.

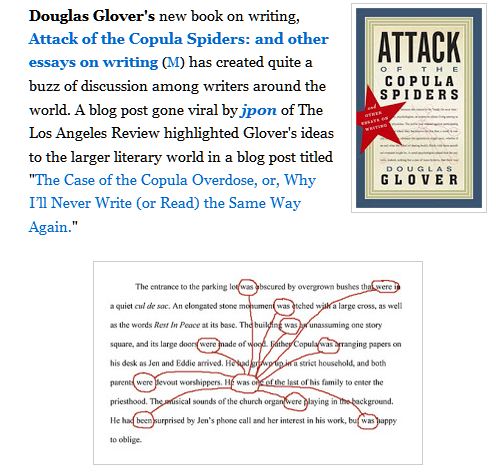

Douglas Glover, in his essay “How to Write a Short Story Structure: Notes on Structure and an Exercise,” published in Attack of the Copula Spiders, defines an image pattern as “a pattern of words and/or meanings created by the repetition of an image.” (33) Each repetition is not simply a duplication of the first, however, for the most interesting patterns require variation. Think of the famous bars from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony: if they were played fifteen times in succession without variation, how grating they would be! But Beethoven artfully incorporated variety into the score so that whenever it returns to the familiar phrase, the audience can appreciate it. Similarly, in visual art, the most successful images employ repetition with thoughtful variation to create unity. Even Andy Warhol’s famous silkscreened Campbell’s Soup Cans are slightly different from one another: each can bears a different label, “black bean,” “tomato rice,” “vegetable,” “green pea,” and so forth. The “cheese” soup even bears a visually different label, with a yellow banner spanning its front.

Glover’s essay names some specific options for varying a repeated image. First, in successive appearances, the author may add a piece of significant history—that is, repeat the image but include new information or detail that the reader wasn’t aware of in a previous iteration. Second, the author may use “association and/or juxtaposition,” pairing the image with another, previously unrelated, image so as to enlarge or alter its meaning. Third, the author may use what Glover calls “ramifying or ‘splintering’ and ‘tying-in,’” where one or more parts of the image are extracted and repeated, then put together again in a later iteration (33).

Image patterning gives a story “an echo chamber effect (or internal memory—important for giving the reader a sense that there is a coherent world of the book,” “rhythm,” and “a root or web effect that promotes organic unity (the threads connecting the pattern in the text are like the roots of a tree holding the soil together)” (33). While Glover is speaking of fiction, the principles of image patterning are equally applicable to non-fiction writing. Essayists and memoirists alike can select images from real life, interpreting such images to add new layers of meaning and symbolism with each recurrence.

I would add that syntactical patterns—even those that are not primarily visual—are capable of providing the above functions in a given work, just as image patterns do, when they are repeated with variations.

Dillard’s book nearly bursts to overflowing with both of these types of patterns. Repetition of syntactical and image patterns lends unity to a work, while variations on those patterns provide movement, or circulation. Still, the process through which image patterns and syntax “work” in the hearts and minds of readers, when they are working well, feels rather mysterious. One writer friend remarked to me that, despite years of studying literature and the writing craft, when she reads books by Marilyn Robinson, they still seemed “like magic.” Similarly, when I first read Annie Dillard’s remarkable Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, I was tempted to ascribe its flow, its circulatory system, to sorcery. But upon subsequent, closer, readings, I began to see patterns emerging, and an inherent, carefully ordered structure—evidence of craftsmanship, not dark arts. The first pattern jumped out to me, suddenly, much the same way that a stereogram image suddenly pops out, unmistakably visible, so that the viewer wonders, “How did I not see that before?” It was the repeated phrase, “the tree with the lights in it,” a specific pattern of text that recurs fourteen times throughout the book, and which, in section III, I will discuss in depth.

Shortly after that first pattern appeared to me, other images began to shimmer from the text: a mockingbird’s graceful free fall, a giant water bug that sucked a frog out of its skin, sharks in a feeding frenzy limned in light, the goldfish named Ellery Channing. [2] I ordered a sturdy hardcover copy of the book for the express purpose of tracking down every image pattern that I could find, cross-referencing them in the margins, coding them with watercolors, and indexing my finds in a chart like a concordance (Appendix A). I’ve included scanned images of some relevant pages so that you can follow this process. I should stress that it was only in the course of many successive readings that many of these patterns became apparent to me; mostly, that which you see sketched out in watercolor and marginalia would remain in the unconscious levels of a reader’s mind for the first reading. The purpose of these added visual elements was to make visible some of the subtle connections that a reader’s mind would perceive as a marvelous, almost supernatural, sense of flow.

Using my concordance of recurring images (for example, planet/earth, sail, giant water bug that sucked a frog, goldfish, tree with the lights in it, snakeskin, et cetera), I next found a photograph to represent each one, and obtained permission from the photographers to use them for my purposes. In some cases, as with the goldfish and sea-anchor, I drew my own and scanned it. I reproduced numerous copies of each photograph or drawing onto sticker paper so that I could place a relevant hand-made sticker as a tag onto each page where a given image appears. Some pages, as in the example above, have multiple stickers, showing that these are pages where Dillard has tied several different images together. On page 128, Dillard links in one sentence several key images: the planet, the giant water bug that sucked a frog, Tinker Creek, the flight of three hundred redwing blackbirds, the goldfish bowl, and the snakeskin. In pencil I’ve drawn connections between repeated phrases, such as solar system, and related phrases such as giant water bug on page 128 and giant water bug’s predations on page 129, or goldfish bowl, the fringe of a goldfish’s fin, and fish’s fin on 129. In margins, I’ve noted the page numbers for other instances when these same visual images or textual patterns occur, such as the Kabbalistic tradition which turns up on pages 30, 198, 261, and the phrase spotted and speckled, which alludes elsewhere in the text to the biblical Jacob’s “speckled and spotted” flock (pages 145 and 239). The word speckled occurs on pages 145, 179, 239, 242, 266, and 271 and, when its various contexts are considered together, serves to link the notion of Jacob’s speckled and spotted flock to the natural world’s intricate details as well as its imperfections. (For a complete list of all the references to these and other repeated images, see Appendix A.)

With the aid of these and other visual annotations, Dillard’s patterns became more apparent—not only the interplay of recurring images, but also some of the syntactical patterns that characterize her idiosyncratic style: parallelism, repetition of key words and phrases, frequent use of colons and question marks, and lyricism through poetic devices. Most delightfully, there is playfulness—Dillard accents her deadpan humor with the use of homophones and other types of word play: puns, allusions to nursery rhymes and jokes (“Like the bear who went over the mountain, I went out to see what I could see,” on page 11), as well as the re-appropriation of popular expressions and aphorisms (“If you can’t see the forest for the trees, then look at the trees; when you’ve looked at enough trees, you’ve seen a forest, you’ve got it,” page 129).

II. Syntactical Patterns

Virginia Tufte opens her book Artful Sentences: Syntax as Style with an epigraph by Anthony Burgess—“And the words slide into the slots ordained by syntax, and glitter as with atmospheric dust with those impurities which we call meaning,”—and adds the following commentary, “Anthony Burgess is right: it is the words that shine and sparkle and glitter, sometimes radiant with an author’s inspired choice. But it is syntax that gives words the power to relate to each other in a sequence, to create rhythms and emphasis, to carry meaning—of whatever kind—as well as glow individually in just the right place.” Syntax is what gives sentences that remarkable sense of flowing movement, allowing meaning to glitter. Carefully constructed syntax at the sentence and paragraph level creates larger movement that helps to propel lyrical writing, in the way that the motion of water flowing down small mountain streams create a river’s strong current out toward sea. In Dillard’s writing, we read not so much because we want to know what is happening (which is, in truth, little more than Dillard sitting watching animals, thinking about religious mystical traditions, and pondering physics and evolution), but rather because of the way in which Dillard expresses her thoughts and feelings: the power of words as they relate in sequence, the rhythms and emphases that syntax creates, and the multiple, shimmering meanings that those words and images carry. In short, syntax and imagery advance the narrative, providing both unity, through repetition and parallelisms, and movement, through variations and rhythm.

Syntactical tactics: parallel structures, repetition, lyricism

Dillard grounds many of her metaphors in parallel sentence structures. For instance, on the first page, after describing an old tomcat who used to wake her by treading with bloody paws on her bare skin, making her look as though she’d been “painted with roses,” she poses the question, “What blood was this, and what roses?”

A compound sentence: the first half inquiring about blood, the second about roses. She follows this short interrogative sentence by another, more involved sentence, which twice pairs “roses” and “blood,” suggesting a variety of possible metaphors (some negative, some positive) for each: “It could have been the rose of union, the blood of murder, or the rose of beauty bare and the blood of some unspeakable sacrifice or birth” (Dillard 1). She continues: “The signs on my body could have been an emblem or a stain, the keys to the kingdom or the mark of Cain”(2). The paired clauses accentuate the multiple possibilities for paired meanings, for opposing meanings. What’s more, the paired clauses carry the same meter and also rhyme with one another (“stain” / “Cain”), attracting the reader’s special attention to this sentence. These parallel constructions set up the reader for what is ahead: room for opposing interpretations of what we find in the natural world.[3] These musings on “union” and “murder,” “beauty,” and “sacrifice or birth” will be followed up with stories of union, murder, beauty, sacrifice, and birth, featuring creatures such as female praying mantises, which eat their mates while they mate, and ichneumon wasps, which are lucky if they lay their eggs before the young begin to hatch and eat their mothers from inside. Dillard’s richly paired, carefully crafted sentences have the power to hold within themselves, on a micro-scale, the same extremities of beauty and horror found in the book as a whole, creating a fractal pattern. Just as these sentences weigh beauty against the violence and suffering inherent to the natural world, so do the paragraphs and chapters that hold them. This is an appropriate structure for a book about nature, as nature tends to be structured in fractals: the veins of leaves, networks of waterways, branches of trees, circulatory systems of human beings. Another example of Dillard’s parallel sentence structures occurs in the passage that introduces Tinker Creek and Tinker Mountain.

The creeks—Tinker and Cavern’s—are an active mystery, fresh every minute. Theirs is the mystery of the continuous creation, and all that providence implies: the uncertainty of vision, the horror of the fixed, the dissolution of the present, the intricacy of beauty, the pressure of fecundity, the elusiveness of the free, and the flawed nature of perfection. The mountains—Tinker and Brushy, McAfee’s Knob and Dead Man—are a passive mystery, the oldest of all. Theirs is the one simple mystery of creation from nothing, of matter itself, anything at all, the given. (2-3, emphases mine to show parallelism)

By presenting these metaphors—the creeks and what they represent, and the mountains with what they represent—as paired sentences running parallel to one another, Dillard heightens the contrast between the metaphors. The first two sentences lay out the creeks, their specific names, and what they represent metaphorically: “active mystery,” “all that providence implies.” The second pair of sentences lays out the mountains, their names, and the metaphor that Dillard intends for the mountains to represent: “passive mystery,” “one simple mystery of creation.” She arranges the paragraph with a set of two paired sentences, each with corresponding clauses and even the dashed parenthetical phrases placed in parallel (Article, noun, em dash, paired specific names, em dash, being verb, article, adjective, noun, etc.). I’ve coded the creek-related sentences in blue and the mountains in purple. It’s as if she’s placed signposts reading, “Creek metaphor this way! Mountain metaphor that way!” The reader pauses, reflects, notices the subtle distinctions between the parallel structures, the creeks versus the mountains—ah, one is active mystery, the other passive—in keeping with human perception that rivers visibly move, while mountains appear immutable. The former represents “all,” the latter, “one.” Soon Dillard ends the paragraph with two short sentences that confirm the contrast between the metaphors: “The creeks are the world with all its stimulus and beauty; I live there. But the mountains are home” (Dillard Pilgrim 3). These final sentences, too, are parallel, although they are punctuated differently, and have different lengths, forcing the reader to slow the pace of reading in order to think about the differences between “living there” and “home.”[4] [5]

Repetition, like parallelism, can be a powerful syntactical tool. As Virginia Tufte writes, “Repetition and variation constitute that dual essence of prose rhythm, as they do of form in music or in painting. Many types of parallel arrangement, of balance and calculated imbalance in phrase and clause, of repetition and ellipses, pairings, catalogings, contrasts and other groupings, assembled together into distinct prose textures, can contribute to the unique rhythm of almost any kind of prose” (Tufte 234). Repetition captures attention, piques curiosity, builds emphasis, and when interlaid between disparate parts, repetition serves as a connector.

Dillard often repeats a significant phrase or sentence, sometimes with small variations. For example, she ends chapter 4 with, “catch it if you can,” then repeats the phrase as the opening to chapter 5.

Chapter 5, primarily a meditation about time being a continuous loop, focuses on a knotted snakeskin that Dillard found in the woods, but is also a reflection on seeking divine power or spirit, which Dillard compares to the mythical hoop snake that rolls along with its tail in its mouth: “the spirit seems to roll along like the mythical hoop snake with its tail in its mouth.” For good measure, she also throws in an allusion to the biblical Ezekiel’s account of seeing the wheels: “‘As for the wheels, it was cried unto them in my hearing, O wheel.’” Dillard concludes with a long sentence that personifies the spirit, “This is the hoop of flame that shoots the rapids in the creek or spins across the dizzy meadows; this is the arsonist in the sunny woods: catch it if you can” (76). She seems to be conflating time with spirit, so that catch it if you can might refer to both. Right across the page spread, chapter 6 opens with the short sentence, “Catch it if you can” (77). The repetition of catch it if you can gives continuity between the two chapters, while at the same time, because it is such an active, daring, quick sentence in its second appearance, propels the narrative forward. A few pages into the new chapter, catch it if you can is repeated to begin another section—but now in this case the sentence is loaded with a somewhat different meaning, as here Dillard discusses not time as a continuous loop, nor spirit, but what it means to dwell fully in the present moment; awareness, rather than time or spirit, is the thing to be caught. “Catch it if you can. The present is an invisible electron; its lightning path traced faintly on a blackened screen is fleet, and feeling, and gone” (79).

Thus far, there have been three replications of catch it if you can, and three associated meanings. Next, over a hundred pages later, in quite another context, Dillard repeats the text pattern, changing one word: it for them, so as to create a variation on the motif.

But now she is speaking of fishing; the pronoun them refers to fish. “You can lure them, net them, troll for them, club them, clutch them, chase them up an inlet, stun them with plant juice, catch them in a wooden wheel that runs all night—and you still might starve. They are there, they certainly are there, free, food, and wholly fleeting. You can see them if you want to; catch them if you can” (186). Notice that she has slyly inserted a reference to “a wooden wheel that runs all night,” which suggests the shape of that continuous loop of time, the hoop snake spirit, and Ezekiel’s wheel from the previous context.[6] But in this context, the pattern carries a new meaning: fish, which here also connote Christ, as Dillard explains that the fish was an early symbol for Christ. (The origin of the fish as Christian symbol might have come because of Jesus’ practice of calling fishermen to follow him, teaching them to “fish for men.”) Dillard has loaded the pattern: “The more I glimpse the fish in Tinker Creek, the more satisfying the coincidence becomes, the richer the symbol, not only for Christ but for the spirit as well” (186). So now, catch them if you can refers to fish, which in turn refers to Christ and spirit. It’s a serious sort of pun.

What a nice trick this is, for by this Dillard has not only added new layers of meaning, but also returned to an earlier one, that of spirit. The symbolism has come full circle—like a continuous loop or hoop or wheel. Fitting!

Later, Dillard again varies the pattern when she writes overtly of stalking the spirit: “You have to stalk the spirit, too . . . and hope to catch him by the tail” (205). About thirty pages pass before yet another variation, “Nature seems to catch you by the tail” (236). Such repetitions, “catch it if you can,” and variations, “catch [him/you] by the tail,” function like a musical theme and variation, providing both unity and variety as the book moves forward. The paragraph that begins with “Nature seems to catch you by the tail” concludes with a list of the tailless animals that got away, adding further rhythmic variation to this text pattern.

One additional thought to note: perhaps the phrase “catch . . . by the tail” alludes to the children’s rhyme “catch a tiger by the tail.” The earlier version of the pattern catch it if you can seems to allude to children’s games (“catch” with a ball), or possible the fairy tale story of the gingerbread man who cries “catch me if you can.”

Another example of phrase repetition is it is chomp or fast. This phrase appears twice in a row on page 237, with only a section break in between its two occurrences:

Before the whole phrase, “it is chomp or fast,” appears at all, however, it is foreshadowed, as the word chomp shows up three times scattered throughout page 227: 1) “I looked beyond the snake to the ragged chomp in the hillside where years before men had quarried stone,” 2) “Is this what it’s like, I thought then, and think now: a little blood here, a chomp there, and still we live, trampling the grass?” and 3) “the world is more chomped than I’d dreamed.”

A few pages later, chomp appears again, this time as a single-word sentence, in reference to parasitism: “the dank baptismal lagoon into which we are dipped by blind chance many times over against our wishes, until one way or another we die. Chomp” (234).

One more brief example: The sentence, “What we know, at least for starters, is: here we—so incontrovertibly—are” (127-8) leads into a brief meditation on the brevity of life, and the importance of working, during the brief time we are alive, at making sense of what we see, in order to discover “where we so incontrovertibly are” (128). By adding a mere w and omitting the em-dashes, Dillard varies the phrase as she almost repeats it, so that it might stick in the reader’s mind for later. Later comes more than one hundred twenty pages further, in the chapter about parasites, when she re-states, “Here we so incontrovertibly are” (240), again without the em-dashes. Such recurrences provide connections between separate passages of the book, stitching them together, providing a syntactical clue that the content of these sections relate closely to one another.

Occasionally Dillard interjects sentences that are so lyrical (in terms of meter, assonance, and rhyme) that they are more like what readers typically expect from poetry than prose. In fact it is tempting to believe that some of these lines, which appear on separate pages at great distance from one another, might once have been couplets that were divided up, like twins separated at birth. For example, the lines, “I was ether, the leaf in the zephyr; I was fleshflake, feather, bone” (32), and “I am the skin of water the wind plays over; I am petal, feather, stone” (201).

Most notably, these sentences rhyme (“bone” / “stone”). More subtly, these two sentences share a parallel structure, “I was . . . ; I was . . .”, “I am . . . ; I am . . .” and have a similar meter when read aloud. In both statements, the narrator has broken out of an objective stance to identify herself with inanimate objects in elaborate but earthy metaphors. Thus, although these lines are found 162 pages apart from one another, an astute (you might say, obsessive) reader may recall the first upon reading the second. In my case, I initially thought that the line on page 201 was a direct repetition of a sentence I’d read earlier (my mind remembered the rhythm); it sounded strangely familiar, so I flipped back through the early pages until I found its correlative. Even readers who do not consciously observe these relationships—probably most first or second-time readers—will sense that the book flows, that there is an ineffable something that unifies the book’s early pages with its later ones.

Word Repetition

Narrowing the scope from the sentence level to that of words, it’s possible to find a good deal of repetition of particular words, which are freighted with additional meanings and associations each time they appear.

The penultimate paragraph of chapter 1 sets up three images that will run throughout the book, lending unity and movement as the repetitions pile up. Describing the “lightning marks,” or deep grooves that “certain Indians used to carve” into their arrows, Dillard writes:

Certain Indians used to carve long grooves along the wooden shafts of their arrows. They called the grooves “lightning marks,” because they resembled the curved fissure lightning slices down the trunks of trees. The function of the lightning marks is this: if the arrow fails to kill the game, blood from a deep wound will channel along the lightning mark, streak down the arrow shaft, and spatter to the ground, laying a trail dripped on broadleaves, on stones, that the barefoot and trembling archer can follow into whatever deep or rare wilderness it leads. I am the arrow shaft, carved along my length by unexpected lights and gashes from the very sky, and this book is the straying trail of blood.(12)

Thus, Dillard writes in metaphor a manifesto of the purpose of this book. This book is the “straying trail of blood,” and the narrator is the arrow carved by “unexpected lights and gashes.” Throughout the text, it is possible to visually see a “trail of blood,” as the word blood appears every few pages throughout the text (see blood in Appendix A). When I circled the word blood each time it appeared throughout the book, painting each one red, the repeated word blood trailing from page to page resembled the sort of track that a wounded animal might make in its attempted escape.

Similarly, every image pattern, every syntactical pattern, becomes another pathway for the reader to track the quarry, “the game,” as Dillard calls it above (page 12), or “the spirit,” as she calls it on page 76 in connection with the catch it if you can pattern.

Arrows create another such pattern. Soon after this initial reference to arrows at the end of chapter 1, the next chapter begins with a story of the child Annie Dillard, at age six or seven, amusing herself by hiding pennies and drawing chalk arrows on sidewalks pointing the way to the hidden coins. Like the arrow that inflicts the wound on the hunted game animal, these arrows also begin a trail to guide a lucky passerby to hidden treasure. “After I learned to write I labeled the arrows: SURPRISE AHEAD or MONEY THIS WAY. I was greatly excited, during all this arrow-drawing, at the thought of the first lucky passer-by who would receive in this way, regardless of merit, a free gift from the universe” (14). Dillard, now an adult, a writer, is still at the same game, since each image pattern laid into the narrative functions like a series of arrows, carefully drawn to point the reader toward hidden treasure. Whether we think of them as a trail of blood or as a succession of direction markers pointing toward copper pieces, Dillard’s image patterns give the reader a visible track to follow. The reader, finding another repeated image, recognizes it as familiar and therefore unifying, while the variations on each image invite movement, propelling the reader forward to consider: this time, the arrow is a chalked direction on sidewalk, while the last arrow was an Indian’s hunting weapon. The reader’s curiosity is piqued: What sort of arrow will I find next? What will it point me toward? What will I find at the end of the trail? (see “Arrow/arrowhead” in Appendix A to follow the trail) In reading Dillard, the journey itself is as much of a payoff as any conclusions to which she might lead us. The process of reading is much like hiking through woods: we follow the blazes marked on trees, enjoying the hike not simply for the view we get at the end, but also for what we see along the way.

The passage from page 12 pictured above yields yet another pattern to follow: light. “Lightning” and “unexpected lights and gashes” are both clues to this trail. I painted yellow all occurrences of the words light, sun, gold, and solar, so that throughout my version, splotches of yellow illuminate another way.

So far, the patterns have been composed of words-as-nouns, but verbs can trace patterns too. For example, the verb to cast occurs throughout the text in several different usages, and often appears in conjunction with other image patterns such as Eskimos, the people of Israel, entomologists, and others. Because the word cast appears in conjunction with several different significant patterns, it links these disparate images, unifying several different threads in the text. The word cast appears first on page 43, as the narrator considers spending a winter evening “casting for arctic char,” which, for her, means staying home and reading about Eskimos and their lives. Next, casting appears several times on a two-page spread, associated with Pliny’s account of the invention of sculpture and other contexts:

A Sicyonian potter came to Corinth. There his daughter fell in love with a young man . . . When he sat with her at home, she used to trace the outline of his shadow that a candle’s light cast on the wall . . .

Muslims, whose religion bans representational art as idolatrous, don’t observe the rule strictly; but they do forbid sculpture, because it casts a shadow. So shadows define the real. If I no longer see shadows and “dark marks,” as do the newly sighted, then I see them as making some sort of sense of the light. The give the light distance; they put it in its place. They inform my eyes of my location here, here O Israel, here in the world’s flawed sculpture, here in the flickering shade of the nothingness between me and the light.

Now that the shadow has dissolved the heavens’ blue dome, I can see Andromeda again; I stand pressed to the window, rapt and shrunk in the galaxy’s chill glare. ‘Nostalgia of the Infinite,’ di Chirico: cast shadows stream across the sunlit courtyard, gouging canyons. There is a sense in which shadows are actually cast, hurled with a power, cast as Ishmael was cast, out, with a flinging force.

Note, in these three paragraphs, the piling of associations with the word cast (I’ve circled cast in black ink): “. . . the outline of his shadow that a candle’s light cast on the wall,” “they do forbid sculpture, because it casts a shadow,” “cast shadows stream across the sunlit courtyard,” “there is a sense in which shadows are actually cast, hurled with a power, cast as Ishmael was cast, out, with a flinging force.”

Not only does Dillard use the word cast in several different senses, but she also describes the action of casting, as in sculpture,without specifically naming it as such, when she retells Pliny’s story of a Sicyonian potter in Corinth who physically cast an image of his daughter’s lover using clay and plaster: “she used to trace the outline of his shadow that a candle’s light cast on the wall” (62). Within two paragraphs, cast is used in a variety of different contexts to refer to shadows cast (by candlelight or sun, in reality and in paintings) but also to refer to a person being sent away, “cast out,” as Ishmael was cast out from his father Abraham’s home. Before mentioning Ishmael, Dillard sets us up for it: “Muslims, whose religion bans representational art as idolatrous, don’t observe the rule strictly; but they do forbid sculpture, because it casts a shadow” (Dillard 62). Shortly afterward she inserts a reference to a famous painting, “‘Nostalgia of the Infinite,’ di Chirico: cast shadows stream across the sunlit courtyard, gouging canyons.” Then it comes, the sentence that joins the notion of cast shadows with the other meaning of cast: “There is a sense in which shadows are actually cast, hurled with a power, cast as Ishmael was cast, out, with a flinging force” (63).

At first, the reference to the biblical Ishmael seems unrelated to the rest of the passage, until the reader remembers that Ishmael (who was cast out) is the ancestor of Muslims, about whom Dillard was just speaking. What’s more, there’s also a reference to the nation of Israel in that paragraph: “They inform my eyes of my location here, here, O Israel, here in the world’s flawed sculpture, here in the flickering shade . . .” (62). This reference to Israel is interesting because it is word play in itself, a homophonic allusion to scripture, the Shema, “Hear, O Israel,” from the book of Leviticus, whose text orthodox Jews post in the shadowy doorways of their homes, and also an allusion to the biblical nation of Israel. Ever since Ishmael was cast out, his descendants and those of his step-brother Isaac (today’s Muslims and Jews) have had a good bit of fraternal conflict, and Dillard seems to connect this conflict to the shadowy side of nature, as she next knits in references to disturbing events in the natural world: mating mantises, the giant water bug that sips frogs from their skins, the mantis that preys on a wasp even while the wasp preys on a bee, prompting even the devoted, insect-studying naturalist J. Henri Fabre to write in 1916, “Let us hasten to cast a veil over these horrors” (64). With that last quotation, Dillard has drawn yet another link to the verb cast, and to be certain the reader hasn’t missed the connection, she continues, “The remarkable thing about the world of insects, however, is precisely that there is no veil cast over these horrors” (64).

The phrase “cast a veil” ties this pattern of cast to yet another pattern that has been running through the text, that of nature being like a veiled dancer, “a dancer who for my eyes only flings away her seven veils. For nature does reveal as well as conceal: now-you-don’t-see-it, now-you-do” (Dillard 16). Later, on page 202, the image of veils being removed (not cast, but “removed” and “whisked”) recurs, and is connected to gaining knowledge of the physical world and its workings: “We remove the veils one by one, painstakingly, adding knowledge to knowledge and whisking away veil after veil, until at last we reveal the nub of things, the sparkling equation from whom all blessings flow” (202).

Later, the verb cast appears several times more in a wide variety of contexts: Jesus urging his disciples to “cast the net on the right side of the ship” (186), Dillard walking in the woods where “tulips had cast their leaves on my path, flat and bright as doubloons” (245), and a leaf being “cast upon the air” (253). Finally, cast becomes adjectival for “a cast-iron bell” (261), and the “cast-iron mountains” which “ring” (271). Notice how the word ring, in combination with the descriptor “cast-iron,” further helps the mountain image to resonate with that of the bell. These further appearances of cast lend continuity.

How did Dillard come up with all this? And are the rest of us mortals capable of doing the same? After all, a Harvard neurologist once described Dillard as “almost unbelievably intelligent.” Perhaps it is best—that is, most efficacious and most heartening—for aspiring writers to assume that it was through multiple revisions that Dillard discovered—and chose, developed, added to, and enhanced—such patterns. As Lucy Corin, in her essay “Material,” advises writers, “The story, I like to say and remember, is always smarter than you—there will be patterns of theme, image, and idea that much savvier and more complex than you could have come up with on your own. Find them with your marking pens as they emerge in your drafts” (Corin 87). Corin advises writers to then make the most of such patterns, expanding and accentuating them, and controlling their effect. Annie Dillard, in The Writing Life, seems not to disagree: “You write it all, discovering it at the end of the line of words. The line of words is a fiber optic, flexible as wire; it illumines the path just before its fragile tip. You probe with it, delicate as a worm” (7). By “it,” Dillard means the thing you suddenly realize is the new point of what you are writing. Because of this statement and others she makes in The Writing Life, I believe that Dillard means it is in the process of writing, of re-reading one’s work, and revising, re-writing, that the author delicately discovers such patterns and discerns whether to keep them, when to expand them. We writers must probe our own texts to find the intelligence that is there.

For novice writers, this is good news: patterns don’t typically appear all at once in their final form, but they do sometimes suggest themselves. It is the good work of writers to become aware of such emerging patterns, work them with intention and deliberation, and carefully craft the overall work. Perhaps it would be prudent for us all to read our own work with watercolors in hand in order to better discover what is there!

Lyricism/Poeticism

Lyricism is Dillard’s not-so-secret weapon when it comes to syntax in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. Her persistent application of poetic devices such as similes and extended metaphors, alliteration, assonance and consonance, even rhymes and homophones, create a strong, consistent, musical voice that both unifies the tone of the work and helps it to move with a strong rhythm, as in this memorable passage, which I quoted in part earlier: “I filled up like a new wineskin. I breathed an air like light; I saw a light like water. I was the lip of a fountain the creek filled forever; I was ether, the leaf in the zephyr; I was flesh-flake, feather, bone” (Dillard 32).

Two frequent poetic devices in Dillard’s work are metaphor and simile. A good example of Dillard’s use of extended metaphor and related similes occurs when she finds herself in a meadow filled with grasshoppers. In the first three pages of chapter 12, while Dillard describes the grasshoppers, nearly every simile and metaphor she uses relates to war, an apt metaphor as she describes these apparently armored insects invading the meadow. Even the chapter title, “Nightwatch,” suggests a soldier on duty keeping watch at night.

War-related similes include: “barrage of grasshoppers,” “such legions,” “blast of bodies like shrapnel exploded,” “ordinary grasshoppers gone berserk,” “ranks,” “coat of mail.” Also “mustered this army,” “detonated the grass,” “sprang in salvos,” and “ricocheted” (207-9). By restricting metaphors to such a genre, Dillard not only maintains a specific, dangerous tone as she describes the process by which ordinary grasshoppers adapt into locusts, but also creates writing that coheres, syntax that advances forward.

Extended metaphors lend lyricism and also unify. Another example of extended metaphor is the recurring image of a magician in a circus tent show (ah, you remember the magician pattern, yes?), as well as splinters from, or variations on, this image. The metaphor begins in the first chapter, just after Dillard has described a spectacular sunset. Then she waxes metaphoric, comparing the optical wonders of nature to a carnival act performed by a fast-acting magician:

Some of the images within the extended metaphor above show up again and again throughout the book, “splinters” from an image pattern. Examples of splinters from this passage that recur elsewhere are the magician, tent, show, rabbits, scarves, and the words bland and blank (these last two, though not specific to magic shows in general, Dillard more than once associates with the magician image). Such words, in future instances, are joined to the idea of sky/heaven as a dome or tent over the earth (see “magician” in Appendix A). Dillard refers to several of these images again later: “Some days when a mist covers the mountains, when the muskrats won’t show and the microscope’s mirror shatters, I want to climb up the blank blue dome as a man would storm the inside of a circus tent, wildly, dangling, and with a steel knife claw a rent in the top, peep, and, if I must, fall” (31).

The word show, applied to impressive sunsets and cloudscapes, also refers to stalking muskrats, as in the above quotation from page 31, and again, “If I move again, the show is over” (195), and once in regard to a town’s attempt to exterminate starlings—“the whole show had cost citizens two dollars per dead starling” (37). It is interesting to note that an image that first appears in connection with rich beauty—an astonishing sunset so impressive that it is like a carnival magician’s act—is later applied to horrors: an attempted mass extermination of invasive starlings, and later, to a gruesome Eskimo myth. In the myth, an ugly old woman who, jealous for her handsome son-in-law, kills her own daughter and removes the face to lay as a mask over her own in order to trick the son-in-law into loving her. After recounting the story of the old woman and the skin mask, Dillard applies the tale metaphorically to the natural world, wondering whether the beauty she has sometimes witnessed in creation is really just a clever disguise for nature’s ugliness and cruelty: “Could it be that if I climbed the dome of heaven and scrabbled and clutched at the beautiful cloth till I loaded my fists with a wrinkle to pull, that the mask would rip away to reveal a toothless old ugly, eyes glazed with delight?” (266) Note the similarity between this sentence and the previous one, from page 33, about climbing the dome of the magician’s tent; using syntax and word choice, she’s drawn a striking parallel between these two passages.

Through repeating the metaphor of a magician’s show in different contexts, Dillard complicates and enriches its meaning. In so doing, she manipulates the magician image so that it functions similarly to the images of tomcat, blood, and roses on the first page, raising questions about beauty and horror, sacrifice, birth, and death. Nothing is ever boiled down to a simple, single representation; every image is multi-faceted, open to further exploration and interpretation.

Alliteration, assonance, consonance

A potential danger in Dillard’s penchant for piling together so many disparate images—cats, magicians, Kabbalistic mystics, physicists, giant water bugs, shadows, artists, clouds, and biblical figures, just to name a few—is that some of them might not seem to fit. Dillard averts danger by connecting all the dots, drawing a web of relationships between image sets. But she also takes a syntactical approach, which includes using similar sounds in a given passage so that the music of the language itself provides cohesion within sections. Returning again the cast passage, an aforementioned pattern composed of quite a variety of parts, a reader, intoning it aloud, can hear how similar sounds help the differing parts to cohere.

The lyricism that comes from alliteration, assonance, and consonance helps hold the cast paragraphs together. For example, re-read aloud Dillard’s description of a painting by the artist di Chirico: “cast shadows stream across the sunlit courtyard, gouging canyons” (63). The many hard cees that begin words (alliteration), combined with the soft esses (consonance) in “cast,” “shadows,” “stream,” “across”, “sunlit, “canyons,” as well as the many short “a” sounds (assonance), elevate the description of the di Chirico painting to art in itself, a line of poetry. These devices combine for a rich, musical sound that flows audibly in the same way that the several images of cast and casting flow visually. Those hard cees, soft esses, and short a sounds recur throughout the paragraphs so that the sentences musically flow. This is just one example of how poetic devices create lyricism; the book is rife with these techniques.

Homophones

Sometimes Dillard seems to have such serious fun with the sounds of words. Returning again to the cast passage, remember the homophone of “here, O Israel,” which sounds like the beginning of the traditional Jewish prayer, the Shema Yisrael: “hear, O Israel.” This homophone is appropriate in context, for Dillard is discussing how cast shadows create a sense of place and presence—a sense of being “here”—while at the same time, she alludes to the story of Isaac and Ishmael from the Torah and Old Testament. These are serious, mysterious topics, yet a reader can hardly refrain from smiling to see the play on hear/here.

Another homophone appears in the context of an important central image pattern, that of Dillard’s first time seeing “the tree with the lights in it,” an experience so vital that she eventually builds a book around it (and I’ve built the next section of this essay around it).

Then one day I was walking along Tinker Creek thinking of nothing at all and I saw the tree with the lights in it. I saw the backyard cedar where the mourning doves roost charged and transfigured, each cell buzzing with flame. I stood on the grass with the lights in it, grass that was wholly fire, utterly focused and utterly dreamed. It was less like seeing than like being for the first time seen, knocked breathless by a powerful glance. (33)

But its import is no hindrance to a little serious word play: Dillard writes “wholly fire” (33), suggesting “holy fire.” This homophonic association is in keeping with other religious phrases that appear on the same page describing this event which is, for Dillard, akin to a religious experience: “pearl of great price,” “literature of illumination,” “litanies,” “ailinon, alleluia.” For Dillard, seeing this light-shot cedar is as profound a moment as seeing a vision, and she describes it in language that suggests biblical figures who experienced divine fire: she even uses the term transfigured to heighten the religious metaphor, for in the biblical gospel account, Moses (who witnessing a flaming bush that did not burn up) and Elijah (prophet who called down divine fire) were both present with Jesus on the Mount of Transfiguration.

This re-appropriation of holy language is wholly Dillard, who ably commands a wide array of syntactical tactics: repetition, parallelism, alliteration, assonance, consonance, and homophones.

Image Pattern: ‘The Tree with the Lights in it’

Dillard’s account of witnessing a particular tree lit up by the evening sun becomes emblematic of her role as a pilgrim at Tinker Creek: she learns to see transcendence in nature. Dillard refers to the “tree with the lights in it” many times throughout, honing its essence but also yielding greater ambiguity (nature is awe-inspiring in sometimes horrific ways), until it becomes one of the central images standing in for Dillard’s conclusion, if there is such a thing, of her philosophical meditation on nature and what it means: “The universe was not made in jest but in solemn incomprehensible earnest. By a power that is unfathomably secret, and holy, and fleet. There is nothing to be done about it, but ignore it, or see” (Dillard 270). Over successive repetitions, she develops this image in such a way that it relates to the Heraclitus epigraph that Dillard chose for her book, “It ever was, and is, and shall be, ever-living Fire, in measures being kindled and in measures going out.”

Introducing . . . “the tree with the lights in it.”

Dillard borrows the phrase “the tree with the lights in it” from another source, a “wonderful book by Marius von Senden, called Space and Sight,” which chronicles the experiences of newly sighted people—those who’d had cataract operations to cure lifelong blindness. Dillard quotes Van Senden describing one such little girl: “‘She is greatly astonished, and can scarcely be persuaded to answer, stands speechless in front of the tree, which she only names taking hold of it, and then as ‘the tree with the lights in it’” (Dillard 28). The former blind girl doesn’t understand dimensionality, so sees the negative space around the tree’s branches as lights. Dillard wonders what it would be like to forget dimensionality, to see as if for the first time, and makes a great effort to try to imagine it, wandering peach orchards all summer searching for “the tree with the lights in it” until:

Then one day I was walking along Tinker Creek thinking of nothing at all and I saw the tree with the lights in it. I saw the backyard cedar where the mourning doves roost charged and transfigured, each cell buzzing with flame. I stood on the grass with the lights in it, grass that was wholly on fire, utterly focused and utterly dreamed. It was less like seeing than like being for the first time seen, knocked breathless by a powerful glance. The flood of fire abated, but I’m still spending the power. Gradually the lights went out in the cedar, the colors died, the cells unflamed and disappeared. I was still ringing. I had been my whole life a bell, and never knew it until at that moment I was lifted and struck. I have since only very rarely seen the tree with the lights in it. The vision comes and goes, mostly goes, but I live for it, for the moment when the mountains open and a new light roars in spate through the crack, and the mountains slam. (Dillard 33-34, emphases mine)

The passage contains Dillard’s next two repetitions of the phrase “the tree with the lights in it,” a pattern of text that we read in this exact wording a total of fourteen times before the book’s end (see Appendix C). Within the above quotation, there’s Dillard’s first appropriation of the original image pattern, and also the first “splintering” of the image that Glover spoke of (“the grass with the lights in it”), which I have italicized. Next there’s the reversal of the image (“the lights went out in the cedar”), with words fashioned carefully to create a new rhythm (variation).

The passage contains Dillard’s next two repetitions of the phrase “the tree with the lights in it,” a pattern of text that we read in this exact wording a total of fourteen times before the book’s end (see Appendix C). Within the above quotation, there’s Dillard’s first appropriation of the original image pattern, and also the first “splintering” of the image that Glover spoke of (“the grass with the lights in it”), which I have italicized. Next there’s the reversal of the image (“the lights went out in the cedar”), with words fashioned carefully to create a new rhythm (variation).

The tree / with the lights / in it

The lights / went out / in the ce-dar

Before the first paragraph ends, Dillard repeats the initial image pattern, “the tree with the lights in it,” to burn its significance (that though it is fleeting, it reappears from time to time) into the reader’s unconscious mind, a proper set-up for the phrase’s next occurrence forty-eight pages later.

The Real and Present Cedar

The next occurrence of the image pattern “the tree with the lights in it” does two things: 1) it first reminds the reader of the cedar and its initial meaning: to see something as if for the first time, as if it were a divine vision, then 2) adds another meaning—this time, to be fully aware of the present moment while living it—by interweaving with a new image pattern, “patting the puppy.” Dillard sets this up by describing in sensory detail her experience of stopping at a roadside gas station where she finds a beagle puppy. She imbues the experience and image of “patting the puppy” with a particular meaning: that of being in the present moment, of being in the particular, or opening a door into the present. Then she remembers the previous experience of seeing “the tree with the lights in it,” and connects it to the present moment of interacting with the puppy. The result of Dillard’s interweaving the two image patterns is that the meaning of the new image (the importance of being fully present in a particular moment) is now added to the previous image of the cedar. Dillard doesn’t expect the reader to leap to this conclusion, but painstakingly connects the dots, essaying:

I had thought, because I had seen the tree with the lights in it, that the great door, by definition, opens on eternity. Now that I have ‘patted the puppy’—now that I have experienced the present purely through my senses—I discover that, although the door to the tree with the lights in it was opened from eternity, as it were, and shone on that tree eternal lights, it nevertheless opened on the real and present cedar. It opened on time: Where else? (80)

Later, lest the reader muddle the two associated image patterns, Dillard neatly clarifies the distinctions between them: “Seeing the tree with the lights in it was an experience vastly different in quality as well as in import from patting the puppy. On that cedar tree shone, however briefly, the steady, inward flames of eternity; across the mountain by the gas station raced the familiar flames of the falling sun” (Dillard 80).

Next Dillard adds variety to the pattern with more “splintering,” putting the image of “the tree with the lights in it” into the reader’s mind indirectly. How does she do this? At first, she simply recounts a story of an old king, Xerxes, who once experienced an encounter with a tree so powerful that he halted his troops for days while he contemplated the tree and got a goldsmith to work its image onto a medal. After the story, Dillard drops textual clues. “We all ought to have a goldsmith following us around. But it goes without saying, doesn’t it, Xerxes, that no gold medal worn around your neck will bring back the glad hour, keep those lights kindled so long as you live, forever present?. . . I saw a cedar. Xerxes saw a sycamore.” (Dillard 88, italics mine) Dillard ties the splintered image to the original pattern with careful word choices—“lights” and “I saw a cedar.” Oh yes, the reader remembers, she’s talking about that tree, the cedar, the tree with the lights in it. This time another layer of meaning is wrapped around the image: we make talismans to try to remember the visions we’ve seen in the past. Xerxes with his medal, Pascal with his piece of paper scrawled with his recollection of a mystical experience that he called his nuit de fuit, “night of fire” (which Dillard abbreviates to simply one word “FEU” on page 88), Dillard with her book Pilgrim at Tinker Creek—these are the attempts people make to hold on to fleeting visions and wonders, to remember them by.

Each repetition of the image layers additional meanings and associations, building in scope, while at the same time intensifying the concrete, visual image. I won’t attempt to spell out each meaning here; I’ll save some of that fun for you, dear reader, lest this essay run far too long. All told, six of the book’s fifteen chapters contain the direct phrase “the tree with the lights in it” (see Appendix B), while every chapter contains suggestions of the image pattern—trees and lights. This textual repetition allows the image to serve as a shorthand reminder of each previous occurrence of the image, its prior context, and the previous meanings it has held, so that all the meanings are stitched together throughout the narrative, giving coherence and unity without losing focus.

What Galls the Cedar

Late in the book, Dillard throws in a twist that seems, at first, to question the legitimacy of the image pattern’s previous meanings. “The tree with the lights in it” has meant the beauty of revelation, profound experience, acute awareness of presence in the moment, transfiguration, energy, vision— but now, as she explores the topic of parasitism, something ugly is revealed: cedar trees usually have galls. “And it suddenly occurs to me to wonder: were the twigs of the cedar I saw really bloated with galls? They probably were; they almost surely were. I have seen those ‘cedar apples’ swell from that cedar’s green before and since: reddish-gray, rank, malignant” (242).

This new observation plainly galls Dillard (please pardon the pun, as the author herself surely would), who, in the ensuing long paragraph, dives into a wrestling match with the meaning of evil, as seen in the image of galls on her cedar tree. Viewed in the context of a chapter that examines the horrors of parasitism, disease, and death inherent to creation (ten percent of living things survive only by parasitizing the rest of living things), the galls are terribly significant, not something that can be easily overlooked— unless, apparently, one is caught up in a transcendent vision as she was the first time. Eventually, though, Dillard reconciles the multiple, contrasting meanings represented in her cedar tree:

And I can I think call the vision of the cedar and the knowledge of these wormy quarryings twin fiords cutting into the granite cliffs of mystery, and say that the new is always present simultaneously with the old, however hidden. The tree with the lights in it does not go out; that lights still shines on an old world, now feebly, now bright. (242)

The speaker acknowledges that there are galls. Can the patterned metaphor survive them? Yes. The tree with the lights in it is imperfect, flawed, sick with the ugly protuberances of parasites, yet once, on a particular day, at a particular time, a particular light shone through it, illuminating with such power and beauty that a passing pilgrim was moved to build a book—and a vision of life—around it [7]. The image of “the tree with the lights in it” by now communicates visually what Dillard also articulates another way: “I am wandering awed about on a splintered wreck I’ve come to care for, whose gnawed trees breathe a delicate air, whose bloodied and scarred creatures are my dearest companions, and whose beauty beats and shines not in its imperfections but overwhelmingly in spite of them” (242). This statement, with its reference to a “splintered wreck” joins the “tree with the lights in it” to yet another pattern, that of sailing ships and anchors (anchor itself is holds at least two meanings, as sea anchor but also anchor-hold, the place where an anchorite dwells, as Dillard references on page 2). But the sentence is complex for other reasons, as it ties together several philosophical threads that Dillard has been grappling with, forging an uneasy truce between the notion of the world being a good place, worthy of being embraces and the fact that horrible things occur over the face of the earth daily.

Complex and nuanced though this image pattern has become, it would be much too facile to end even here, Dillard seems to think. Without directly mentioning “the tree with the lights in it,” she inscribes yet another series of allusions, or splinterings. For instance, she refers to a biblical sacrificial practice involving a heifer and—what else?—a cedar tree. “The old Hebrew ordinance for the waters of separation, the priest must find a red heifer unblemished,” burn her, and “into the stinking flame the priest casts the wood of a cedar tree for longevity, hyssop for purgation, and a scarlet thread for a vein of living blood” (267). The phrase cedar tree resonates subtly in the reader’s brain with the previous images of cedar to lend yet another meaning, that of a holy and disturbing sacrifice, to the already rich pattern.

Next Dillard presents what initially seems to be a brand-new image, a maple key (what I’d call a maple seed, or helicopter), but through subtle word choices, provides links between it and the old, familiar tree with the lights in it. When the maple key falls, she eloquently ponders:

The bell under my ribs rang a true note, a flourish as of blended horns, clarion, sweet, and making a long dim sense I will try at length to explain. Flung is too harsh a word for the rush of the world. Blown is more like it, but blown by a generous, unending breath. That breath never ceases to kindle, exuberant, abandoned; frayed splinters spatter in every direction and burgeon into flame. And now when I sway to a fitful wind, alone and listing, I will think, maple key. When I see a photograph of earth from space, the planet so startlingly painterly and hung, I will think, maple key. When I shake your hand or meet your eyes I will think, two maple keys . . .(268)

It’s as if, hidden inside the text, the speaker is whispering, “Reader, what does this remind you of?” A bell— ah, yes, the speaker has spoken before of a bell. Upon her first encounter with the tree with the lights in it, she thought, “I had been my whole life a bell . . .” (33). Meanwhile the words “frayed splinters spatter” suggest the line from page 242, “splintered wreck whose beauty beats and shines . . .” And again, Dillard has often linked the word flame with the tree with the lights in it, as in that first encounter, which used the words flame, fire, and unflamed (this last is phrased such that, although it means the opposite of flame, it yet underscores the image pattern) (33).

Finally, stunningly, in-case-there-remains-any-doubt-about-the-connections-here, let’s-put-it-on-the-very-last-page-so-we-see-for-sure-how-important-it-is, Dillard ties the latest maple-key splinter—via the proxies of the ringing bell and the flame from the long passage quoted above—back to the image pattern: “The tree with the lights in it buzzes into flame and the cast-rock mountains ring” (271). The image pattern is now complete, each stitch knitted securely into the fabric made of all the others. Again, careful phrasing choices, such as “buzzes into flame” on page 271, resonate with earlier wording, “each cell buzzing with flame” on page 3.

Conclusion

Jad Abumrad and Richard Krulwich, in a May 2010 RadioLab podcast called “Vanishing Words,” articulate why readers do the type of deeply analytical work I have done: we all want to get closer to the author that penned those words. From the medieval monks, who spent entire lifetimes making concordances of the Bible, to modern-day literature professors like Ian Lancashire of the University of Toronto, who uses computers to analyze Agatha Christie’s (and other) texts, readers have sought to penetrate the minds of the authors they love. We read to connect.

For me, engaging one text hands-on, with watercolor paints, a sharp pencil, and tiny sticky-backed photographs, was fruitful for recognizing and visualizing textual patterns that would otherwise have remained mostly in my subconscious. But more than that, I felt like I had found a small portal into a favorite author’s mind. Through my study, I became deeply attached to and personally invested in the patterns that Dillard crafts. As a result, my own writing mind is being transformed. On a practical level, this means that I’m more aware of the way I myself use syntax and image patterns, so my latest writing is starting to benefit from the observational and pattern-finding skills I’ve acquired. But on an emotional level, I’ve simply fallen in love with the text. (My husband is a wee bit jealous.)

Not every writer will want to spend a few months taking pens, paints, and pictures to a single text. The physical process is incredibly time-consuming and requires some degree of craftsmanship. Recently, thanks to new advances in technology, a plethora of digital tools exist for readers/writers/scholars to use when actively reading. DevonThink, XLibris, and PapierCraft are a few of the software programs I’ve come across which, to varying degrees, allow readers to interact electronically. A new program, LiquidText, currently under development, will allow readers, via iPad, to view multiple pages at once, add annotations, pull selected paragraphs into a sidebar to organize, group and color-code them, and search for words or phrases. Recent neurological research suggests that the parts of the human brain triggered by iPad and iPhone use are the same as the centers stimulated by empathy, by falling in love. So perhaps it is not completely far-fetched to imagine that these new media will also provide a further means by which readers, scholars, and writers may fall in love with the texts they study, as they explore, like a cartographer, unfamiliar territory in order to know and to map geological features, the edges of landforms, the flow of rivers and streams.

View or download Appendix A, “Selected Image Patterns,” here.

View or download Appendix B, “The Tree with the Lights in It,” here.

Acknowledgments

I owe a debt to several teachers of the writing craft for their insightful instructions on how to read text(s). Lucy Corin’s excellent essay “Material” encourages sketching out the “material” of a given piece of writing, thinking of paragraphs and sentences as objects that can be represented as drawn blocks or lines, in order to detect underlying patterns and structure. Douglas Glover’s personal copy of Thomas Bernhard’s novel The Loser has margins and gutters—nearly all its white space—tightly cluttered with notes in his small, fine handwriting.[8] Glover’s essay “How to Write a Short Story Structure: Notes on Structure and an Exercise” taught me first, what an image pattern is, and second, the importance of attending to them in literature. Virginia Tufte’s instructive Artful Sentences: Syntax as Style lays out for the aspiring writer the elements of syntax in sentences, as well as how it sets the style, tone, and voice of a literary work. Mary Stein’s lecture gave me a framework for thinking about syntax-driven, rather than plot-driven, narrative. Trinie Dalton, in a lecture at Vermont College, described stories as having “circulatory systems,” or some means by which the story moves, or flows. David Jauss, in his essay, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Flow,” credits successful flow to syntax, the way in which sentences are put together.

For the altered book portion of this thesis, I’m grateful to photographers Steven David Johnson and Dave Huth for permission to reprint their images onto sticker paper for my pattern-finding purposes. Dave Huth owns the rights to the photographic images of the giant water bug, dragonfly nymph, frog, and Polyphemus moth; the image of Earth Oceana is used here for non-commercial purposes through a creative commons license by alegri/4freephotos.com; the image of the tree with the lights in it originated with a cedar tree photographed by Ian Robertson, thanks to a creative commons license, and was digitally altered by Steven David Johnson; all other photographs belong to Steven David Johnson and are used with permission. Hand-drawn illustrations are my own.

I wish to also thank artist and poet Jen Bervin for her exquisite textile art that explores the margins of Emily Dickinson’s poetry manuscripts; her work and her conversations with me helped push my thinking about margins and what might happen in them.

For their encouragement and helpful feedback throughout the conception and fulfillment of this project, I thank my advisors at Vermont College of Fine Arts, Richard McCann and Patrick Madden.

Most of all, my greatest thanks to Annie Dillard for writing a book so rich and intricate that I easily spent over six months thinking deeply about it without being bored once. Studying this book was an experience akin to seeing “the tree with the lights in it,” and I’m still spending the power.

— Anna Maria Johnson

Works Cited

Abumrad, Jad and Robert Krulwich. “Vanishing Words.” Radiolab: WNYC. 5 May 2010. Web.

Corin, Lucy. “Material.” The Writer’s Notebook: Craft Essays from Tin House. Portland: Tin House Books, 2009.

Dalton, Trinie. “Good Liar/ Bad Liar: Myth, Symbol, and Choosing the Right Details.” MFA in Writing Summer Residency. Vermont College of Fine Arts. Montpelier, Vermont. 2 July 2010. Lecture.

____________. “Circulatory Systems in Fiction.” MFA in Writing Winter Residency. Vermont College of Fine Arts. Montpelier, Vermont. Jan. 2011. Lecture.

Dillard. An American Childhood. New York: Harper & Row, Inc., 1987.

____________. Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. New York: Harper’s Magazine Press, 1974.

____________. The Writing Life. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 1989.

____________. “Annie Dillard Official Website.” Annie Dillard, 2010. Website. Accessed 7/21/2011.

Glover, Douglas. Attack of the Copula Spiders. Emeryville: Biblioasis, 2012.

Jauss, David. “What We Talk About When We Talk About Flow.” Alone With All That Could Happen. Cincinnati, Ohio: Writer’s Digest Books, 2008.

Stein, Mary. “Mucking Up the Landscape: Poetic Tendencies in Prose.” Número Cinq. Volume II, No. 40. Oct. 5, 2011.

Tashman, Craig. “Active Reading and its Discontents: The Situations, Problems and Ideas of Readers.” CHI 2011. May 7–12, 2011. Vancouver, BC, Canada. Web.

Tufte, Virginia. Artful Sentences: Syntax as Style. Cheshire, Connecticut: Graphics Press LLC, 2006.

———————————-

Anna Maria Johnson’s writing brings together her diverse interests in the visual arts, science and nature, family systems, and spirituality. She studied fiction and creative non-fiction at Vermont College of Fine Art (MFA July 2012). Her short stories and essays have been published in Ruminate Magazine, Blue Ridge Country, Numéro Cinq, DreamSeeker Magazine, Flycatcher Journal, Newfound, and The Mennonite, as well as in the anthology, Tongue-screws and Testimonies. Anna Maria writes, gardens, and makes art along the Shenandoah River’s north fork, where she has lived for seven years with photographer Steven David Johnson and their two daughters. She and Steven are currently collaborating on photo-essays about southern Oregon’s ecology. View their project at www.cascade-siskiyou.org

See also:

James Agee’s Unconventional Use of Colons by Anna Maria Johnson

Whirlpool (All Tremors Cease): Underwater Video Meditation by Steven David Johnsonby Anna Maria Johnson

What it’s like living here in Cootes Store, Virginia by Anna Maria Johnson and Steven David Johnson

The Quirky Bird Art of Paula Swisher by Anna Maria Johnson

Riffing on Whirlpoolsby Anna Maria Johnson & Steven David Johnson

“Meditation on Mary, for Advent,” a sermon by Anna Maria Johnson

The Way To A Man’s Heart is Through His Stomach, or Kitchen Ostinato, a rondeau by Anna Maria Johnson

Off The Page: Novel-in-a-Box by Anna Maria Johnson

——–