Structure is almost everything, says Peter Handke, in an epigraph to this wildly whimsical, often hilarious (“aversion” one character puns on “a virgin”), mid-life, existential love drama between a husband and a wife. Don Druick is a master of musicality. Watch the repetitions: words like scars, quagmire, diminished, love. Jack comically gathers scars as he keeps reasserting that he will not be diminished. The text shimmers. Moments of horror: Jack dropping his hands into a cooking pot full of boiling water. Moments of intense comedy: Audrey misplaces a medallion in a patient’s rectum (the patient is her neighbour, perhaps a lover; the patient gave her the medallion; the medallion bears the words “The fear of everything is love”). To communicate Jack calls his wife’s cell from bed; his wife answers; she is in bed with him. Regularly, the characters revert to speaking in the voices of animals, caws and moos; and just as regularly there are moments of trembling beauty, line after line, poignant and true.

AUDREY Did you say: kyomu?

HUMPHREY Nothingness. The Japanese have four hundred words for it.

AUDREY Really? That many?

HUMPHREY It seems necessary

dg

Will it alter my life altogether?

O tell me the truth about love.

– W H Auden

A human being is a genius while dreaming, fearless and brave….

– Akira Kurosawa

For a work of art, material is almost nothing, structure almost everything.

– Peter Handke

•

A play in eighteen scenes and two acts for six actors.

•

to Jane Phillips, whose own dreams fill a lifetime of shelves.

CHARACTERS

Jack, 60’s

Audrey, 50’s

Jack and Audrey are married; these actors do not double.

Four actors play the following ten characters:

ACTOR 01

Delores – Audrey’s personal assistant

Natalie – a next door neighbor; Humphrey’s wife

Curly – a bad bad dude

ACTOR 02

The Prince Mithroth – Audrey’s dearest friend

Horst – a frightening man

Old Bill – Jack and Sandy’s dead father

ACTOR 03

Humphrey – a next door neighbor; Natalie’s husband

Shlomo – a Hassidic jew

ACTOR 04

Sandy – Jack’s sister

Baby Jack – Shlomo’s precocious son

As well:

Offstage Characters

Pooky, Natalie’s dog

Talking Newspaper

Another Soldier

Chorus, as required

Note: NATALIE has a French accent; HUMPHREY has an English accent.

A visual development: JACK is progressively more scarred as the play proceeds (except: scene 18 where he is scar-free).

•

ACT ONE

SCENE SET 01 – A PROLOGUE

scene one

Jack, at home, paces the kitchen. The air is ripe with the heady odour of baking bread.

JACK I will not be diminished

JACK at his chopping block, the knife fast and furious. He cuts himself.

JACK Jesus, boys, that’ll be another scar. Drat.

The sink is chock-a-block full of simpering wet socks. JACK wrestles with the sodden mass, water spilling everywhere.

JACK Shit.

Suddenly, the lentils on the stove boil over.

JACK turns; the wet socks sloosh to the floor.

JACK Shit.

Smoke cascades from the oven.

JACK Amazing shit, a whole bloody package of it. Drat. It’ll never be as good again. What? Yes. A package of shite. That’s it, boys, that’s it exactly.

PAUSE, as JACK ponders.

JACK But what exactly? Man O man, I don’t understand myself….

JACK goes to the phone. Dials.

JACK (on phone) Delores? Let me talk to Herself.

BEAT.

JACK (on phone) My wife, Audrey….

BEAT.

JACK (on phone) Delores, it’s me, Jack. Jesus….

BEAT.

JACK (on phone) I’m not trying to be funny. Or arrogant. I’m not feeling funny. Or arrogant. Nothing’s funny anymore.

BEAT.

JACK (on phone) I don’t know. A glimmer of something but I don’t get it.

BEAT.

JACK (on phone) I don’t care if you don’t. Understand. Nevermind – too late, too late. There’s no more time, boy O boy, you can’t go backwards.

BEAT.

JACK (on phone) Because time does not move backwards. Everybody knows that. Hey, maybe it doesn’t even move forward. Have you ever considered that?

BEAT.

JACK Tell Herself I’m coming right down.

BEAT.

JACK (on phone) I don’t care.

JACK hangs up the phone.

JACK Drat, another scar.

JACK exits, slamming the door.

SFX: The sound of a car engine starting up. The screeching of tires.

A sudden vicious crash, horrendous.

SFX: Car crash, long and frightening. Shattering glass falling; a blizzard of tiny tinkles.

Silence.

END OF SCENE.

TO BLACK.

•

SCENE SET 02 – OLD BILL GONE

scene two

AUDREY’s medical office. Day.

The blinds are drawn; phone conversations are quietly everywhere.

Prominent: a large collection of colourful Eiffel Tower models.

SFX: The continuous sound of animals.

These two speeches together:

AUDREY (on phone) A leopard, a leopard seen? No…. No no, impossible. Not in my operating room. I mean it makes no sense….. Maybe from a zoo? Maybe a pet?…. Impossible…. Well, don’t go in there – especially if you hear loud growling.

DELORES (on phone) The book of crows? Book of crows? Book of crows? Book of crows?…. No…. No…. No no no. What can it mean? Radical surgery? It worries me. Is it about crows or just a really really good title?

AUDREY and DELORES laugh.

AUDREY (on phone) Anyway, I’m not a vet.

DELORES (on phone) Do you need an appointment?

JACK enters.

JACK Audrey. Audrey. I need to talk.

AUDREY sees JACK; she winks and waves – it’s very friendly.

DELORES I told you, Jack, Jack, on the phone I told you, Jack – she’s busy.

JACK You can be as jealous as you want, Delores – she’s still my wife.

Another phone rings.

DELORES (on phone) Just a mo – the other line.

JACK I was out underwear shopping – I made a call – you’ll never guess what happened. Never. Horrible…. horrible….

DELORES (to AUDREY) It’s for you.

AUDREY (to JACK) Just a minute, darling – I’ll be right with you.

JACK Promise?

AUDREY Promise promise.

DELORES scoffs.

JACK sneers at DELORES.

DELORES She’s working….

These two speeches together:

AUDREY (on phone) Ya…. Ya ya…. She’s pissed off? So? What? Hurt?…. Why? She’s weird. I was home – she could have called…. Hey, I’m not a mind reader, just a doctor…. I’m not even sure I know who she is…. I already did that. I searched a large pile of newspapers looking for someone who might actually have her number….

DELORES (on phone) No…. No…. really?…. Simply, I push the wrong button and the x-ray thing hassles itself apart. Whirring whirring all the time. Wow…. The patients get really nervous…. Ya but now I have no idea how to put it all back together again…. Well what do I care?…. No, really…. Really….

JACK Can I speak now?

DELORES She’s busy.

JACK Drat.

These two speeches together:

DELORES (on phone) Do you think so? Do you? I’m really happy here. Really really happy really really really happy….

AUDREY (on phone) I’m going to read it right now…. Right right now…. Promise promise. Promise promise promise….

AUDREY hangs up the phone.

AUDREY Delores….

DELORES (on phone) I’ve got to go.

DELORES hangs up the phone.

AUDREY (to DELORES) Listen to this.

JACK Am I invisible?

JACK is shushed.

JACK Jesus, what a quagmire.

AUDREY You too, Jack. Listen….

JACK So unkind.

AUDREY Please please please – it’ll be fun.

JACK Nobody cares about me.

AUDREY, making an impatient sound, opens a magazine.

AUDREY Jack…. Jack. Look at me. Stop it. Please wait. I’m working.

JACK Drat.

AUDREY (to DELORES) Here. Here it is. You read this. I’ll start. (reading) OK OK OK, you the patient, right here downstage.

DELORES (reading) Here?

AUDREY (reading) No, right on the lip.

DELORES (reading) Up your moo.

AUDREY (reading, shouting) Up your moo.

DELORES (reading) Moo up you.

AUDREY (reading) You too moo.

DELORES (reading) Too moo you.

AUDREY (reading) Fuck you moo moo.

DELORES (reading) You fuck moo moo.

AUDREY and DELORES laugh – especially AUDREY.

AUDREY It’s hysterical.

DELORES I just love it, I love it.

AUDREY I knew you would. The wise doctor in the world. Ta-taaaaa.

JACK (crow-like, loudly) Caw.

AUDREY (calf-like) Mmuuh.

JACK (crow-like) Kraa caw caw.

AUDREY (calf-like) Mmuuh mmuuh möö.

JACK (crow-like) Kraa caw caw caw kraa….

Suddenly the sun, large very large, large very large as it sets.

AUDREY & DELORES turn to admire it.

AUDREY & DELORES Beautiful.

JACK (quietly) My dad died. Poor old Bill. Poor old Bill is dead. Stroke. Such a quiet word, stroke. Another scar.

END OF SCENE.

•

scene three

Night. JACK and AUDREY in bed; asleep.

JACK is snoring, and somewhat reasonable and gentle it is. He wakes up with a start. In a panic, he opens the light. He flaps around the night table until he finds his cellphone; he dials a number.

The cell phone on AUDREY’s night table rings.

AUDREY (very sleepy, on phone) Hello

JACK (on phone) It’s me.

AUDREY (on phone) Jack? Where are you?

JACK (on phone) What a laugh, eh? I’m right here.

AUDREY turns to see him.

AUDREY What?

JACK (on phone) I woke up and there were a million little red flies swarming all over me and you too. Fucking Mithroth was there too.

AUDREY The Prince Mithroth?

JACK (on phone) My heart’s pounding – I wish you could touch it. I feel very lonely.

AUDREY puts down her phone, and reaches out to JACK.

AUDREY O, you poor thing.

JACK is restless.

JACK (on phone) I feel…. I don’t know…. edgy like….

AUDREY O relax relax relax.

JACK (on phone) Like a wild child.

AUDREY And get off the phone – it’s crazy. I’m right here.

JACK (on phone) O I have a good plan – it doesn’t cost anything.

JACK starts to fondle her.

AUDREY What are you doing?

JACK (on phone) I feel lightheaded and very…. very horny.

AUDREY O for god’s sake – stop it. Stop it.

AUDREY pushes him away.

JACK gets up; wanders about the room.

JACK (on phone) No no no. No no not now. I have a headache. My poor little head aches. What about me what about little lonely me? – I’m horny. So bloody horny. Nothing’s working anymore. Nevermind. What if I can’t write any more novels?

AUDREY sighs.

AUDREY You don’t write novels.

JACK (on phone) I can’t hear you – the connection’s bad.

AUDREY That’s cause I’m not on the bloody phone.

JACK (on phone) What did you say?

AUDREY (shouting) I said: you don’t write novels.

JACK (on phone) But I could if I wanted to. If I had any decent stories. Which I don’t. Drat. What a quagmire. What if I’ve just squandered – wasted – my talent? What if I’m just a fucking old fucking old fuck fuck fucking old sad old has been?

JACK has a penknife.

AUDREY Where did you get that?

JACK (on phone) It’s mine.

AUDREY It looks like mine.

JACK (on phone) It’s mine.

AUDREY What are you doing?

JACK (on phone) Keeping it warm. Useful little scar machine.

AUDREY O, for god’s sake, we don’t need any more scars.

AUDREY takes the penknife from JACK.

JACK Fuck that. I will not be diminished.

AUDREY Relax, for god’s sake. Relax. Please relax. Come back to bed.

JACK (on phone) Why? Are you offering any…. comfort.

AUDREY Yes, I am.

JACK (on phone) Sex would be nice. Ya, sex. Ya. Full throttled, passionate, wild and wet and horribly illegal.

AUDREY Well, I’m not offering that.

JACK (on phone) You’re so hard. Drat drat drat, I’m just a slave to my hormones and desires. And here I thought I was a Buddhist. Maybe I am a Buddhist? Anyway – and I’ve just figured this one out …. or not – something about a package. A package? You’re not listening you’re not listening to a single word I say.

AUDREY picks up her phone.

AUDREY (on phone) I’m here I’m here. I hear you. Yes yes yes, I hear you.

AUDREY gets out of bed.

AUDREY (on phone) Come back to bed.

JACK (on phone) I don’t know. I don’t know.

AUDREY There there, that’s enough telephoning for tonight.

AUDREY takes his cellphone. She tenderly takes him back to bed. She fixes the bed clothes and tucks him in.

AUDREY There there.

JACK I had a dream you had died. Horrible.

AUDREY I had a dream we had never met.

JACK & AUDREY Nightmares.

AUDREY laughs, warm and full.

They kiss. They kiss again.

JACK (crow-like) Caw…

AUDREY (calf-like) Mmuuh mmuuh….

JACK (crow-like) Caw caw….

AUDREY (calf-like) Möö mmuuh möö….

AUDREY laughs with pleasure and anticipation.

JACK & AUDREY Clang. Clang. Clang. Clang. Clang. Clang. Clang. Clang. Clang.

SFX: Moans and building sexual groans.

JACK & AUDREY CLANG CLANG CLANG.

Fireworks.

JACK & AUDREY (quietly) Went the trolley.

BEAT.

END OF SCENE

•

scene four

Temple Beth Shalom, a synagogue. A Friday evening in summer. Services are in progress – we hear Jewish liturgical chanting off.

JACK enters the foyer of the temple. There is a bazaar in progress. Its very active. People are dancing.

JACK looks around.

JACK People people everywhere – everywhere I look there’s new people – and I don’t know any of them.

A Hassidic Jew is sitting on a strange bench – stone and rough wood; decorated with colourful eiffel towers.

SHLOMO Are you looking for something you can’t find?

JACK I am.

SHLOMO The truth?

JACK Ha. Good. Possibly.

SHLOMO Thus you are a philosopher?

JACK But am I really actually looking?

SHLOMO Some do.

JACK Or just mumbling within myself?

SHLOMO That might be the same thing. Jewish? You’re jewish?

JACK Half.

SHLOMO Half jewish? How can this be?

JACK My father was jewish. He went here for services. Prayers.

JACK is a bit unsteady on his feet.

SHLOMO Sit sit – I made this bench myself.

JACK sits.

SHLOMO So, what do you think? Isn’t it beautiful?

JACK I love the Eiffel Towers.

SHLOMO Thank you. It was my son’s idea.

JACK You know, you remind me of my late father.

SHLOMO Is that a good thing?

JACK Eventually it was.

The BABY gurgles.

JACK Your baby?

SHLOMO My son.

SHLOMO beams.

BABY JACK I am the perfect reason to always to be happy.

JACK He talks.

SHLOMO Yes.

JACK But he’s a baby.

BABY JACK Thus, I have the perfect reason for superannuated contentment.

JACK And smart.

SHLOMO Thank you. We are a good team, he and I.

JACK (to BABY) Hello, you dear little thing.

BABY JACK Hello yourself, strange troubled sad man.

SHLOMO We call him: Jack.

JACK Well, isn’t that just something else – that’s my name too. (to BABY) We have the same name, little thing. I must tell my dear darling nephew about that. His name is Bob – he’s a baby too.

BABY JACK Is that relevant here? One must not be too cloying or pathetic with respect to one’s overly rated sentimentality.

JACK O?

SHLOMO No no no, child, don’t abuse the man.

BABY JACK To speak the truth to a penitent, dearest father – as our great talmudic teachers say – is not without the bounds of decorum. (to JACK) You seem out of sorts, if I may be so bold as to pronounce an opinion on your obvious demeanor.

JACK I do feel disoriented – the town seems somehow different. And nothing in my life seems to make sense.

BABY JACK I know what you feel.

SHLOMO But can you know this, my darling son? These same great talmudic teachers – who are our guides in all things – preclude the knowledge of another’s suffering.

BABY JACK But do they, my father? As is said: a person is only a person when and only when she or he is known to all. (to JACK) I do know what you feel, and not just in the indisputably mystical though culturally exhausted kabbalistic connotation.

BABY JACK shrugs.

BABY JACK Change is deep within us. Yet, there are troubles.

JACK There are more mountains than there used to be.

BABY JACK That is indeed terrible.

SHLOMO And challenging.

JACK And more snow on the mountains.

SHLOMO Mountains are the same as love.

BABY JACK Yes, they are, dear father. As is death.

JACK O?

BABY JACK I think, I believe, please please listen to me, that you will require…. a timeshare in these mountains. It will ease your anxiety and erase your sadness.

JACK What?

BABY JACK When I grow up and I am big and wonderful, I will want to work for the Northern Winter Real Estate Association. Perhaps even as their chairman of the board.

SHLOMO Now now, child, don’t overstate your ambition.

BABY JACK But I must, my dearest father – its my destiny. Under my leadership, our product line will be extensive: chalets, time-shares, winter getaways of all sorts….

JACK Ha. Well, I’m sorry – I know that’s not what I need.

BABY JACK Ah well, yes, no, no no, you are right. I have a flash, I’m getting a clear signal. Yes yes, that’s it that’s it – you’d be much better off as a chef.

JACK O? I was – how did you know that?

BABY JACK Once a chef, always a chef.

BABY JACK smiles.

SHLOMO And why – please tell us if its not too problematic for you – so why did you stop?

BABY JACK Too too much indescribable gluttony, I would imagine.

SHLOMO Now now, let the man speak.

JACK Crazy. You wouldn’t believe the yelling, noise, chaos. Just a kitchen, you say. But…. the endless crux of my life. I had a large and succulent tendrons de veau à la provençale in the oven and twenty tarts and farts in the dining room starving for it. Its time its time, yelled my souschef, its time. Alright, fuck you, alright. I shoved my hands into that seething cauldron of an oven – and forgot the mitts.

BABY JACK Your description is startling.

SHLOMO And vivid too.

BABY JACK I actually smell your searing burning flesh.

BABY JACK gags.

JACK I froze, just stood there, debating quite clearly in my mind while my hands burned. White pain intense and banal. What a quagmire. I just gave it all up after I left the hospital. Haven’t worked since. Drat drat drat drat.

BABY JACK Your hands are all scared.

JACK So many scars in a life.

BABY JACK So ugly.

SHLOMO Now now, child.

JACK I’m so confused. Can you help, help me?

SHLOMO But yes, of course. We will sing an opera.

JACK Opera?

SHLOMO We like to sing. We have found, over the centuries – we jews – that it is a good cure for sadness.

BABY JACK But, dearest and beloved father, we need a woman’s voice.

SHLOMO Yes, we do.

SHLOMO looks about.

JACK My dad – old Bill – used to sing a mean countertenor. But he’s dead.

SHLOMO Hmmmmm….

JACK And there’s Audrey – my wife – she used to sing quite well back when we were young.

AUDREY appears.

AUDREY I have no time for this, Jack. I have three surgeries scheduled. And anyway, you know I hate opera.

JACK I don’t think I did.

BABY JACK Frustration and incontinent busyness – surely that will be seen – in the centuries to come – as the principle reasons for the tragic demise of our civilization, so-called.

AUDREY laughs, robust and sexy.

AUDREY You’re a funny little thing. A pity I cannot abide babies.

BABY JACK Do it, dear beauteous hostile lady, sing our opera – how much time can it take?

AUDREY laughs.

BABY JACK The story will be about you.

AUDREY O?

BABY JACK And him.

AUDREY O?

SHLOMO Do it. It will make him feel alive.

AUDREY laughs.

AUDREY O well, for old Jack, the purported love of my life.

SHLOMO Attention, everyone. Attention.

BABY JACK Please listen to my dear and much beloved father.

SHLOMO Now, we do an opera by the wondrous Giacomo Antonio Domenico Puccini….

BABY JACK Amore Abbandonato. And what can ever be wrong with the twin and harmonious notions of love and destiny?

SHLOMO It is the day after Yom Kippur. Maria, the goat girl from the village meets Feivel, the chief rabbi of Riga….

BABY JACK Who is traveling to the great rabbinical court of Torino.

SHLOMO They fall in love….

BABY JACK She with him despite his many unsightly and disfiguring scars.

SHLOMO And he with her despite the fact that she is not jewish.

BABY JACK They spend an extremely meaningful- though chaste – night together under the dining room table.

SHLOMO Locked in each other’s arms

BABY JACK But chaste.

JACK I love this opera.

AUDREY I don’t care for the story.

JACK But its marvelous.

AUDREY Is it?

JACK And somehow familiar. It seems…. perfect.

AUDREY No.

JACK I’m sorry you don’t like it. The opera makes me feel hopeful – I don’t know why.

AUDREY shrugs.

SHLOMO Come come, we start. This is the chorus at the beginning.

CHORUS (singing)

Now the crow may be singing

Singing singing singing

Singing

Singing singing

Instead of the calf

Calf calf calf calf

BEAT.

CHORUS (singing) Instead of the calf.

JACK (singing) Instead of the calf.

JACK stops singing.

BABY JACK But the chorus isn’t finished.

JACK I’m getting a bad feeling. I can’t go on.

SHLOMO But you must.

JACK I was wrong to be so hopeful. The crow and the calf, that’s what I really have. Brutality and conflict. Its the package I’m left with. Drat. Almost nothing – but I guess that’s better then absolutely nothing.

END OF SCENE.

•

scene five

Outdoors. JACK’s building a fire.

SFX The sounds of a Georgian Bay summer night. Loons.

JACK looks up.

JACK Who’s that? (calling) Hello. Hello. I can see you. You’d better come out – I have a gun. (to himself) What a quirky quagmire. O god, is it Mithroth? Drat. Fuck. Fucking Mithroth.

MITHROTH emerges from the shadows.

JACK What the fuck are you doing here?

MITHROTH Don’t let’s quarrel, Jack.

JACK Not a week goes by when I’m not forced to remember you exist. Drat, scars everywhere I look.

MITHROTH O Jack – you’re always mumbling.

JACK – impatient gesture.

MITHROTH Well, then…. Jack, I wonder if you could enhance my thinking on you and Audrey? Is there a problem here?

JACK Fucking Mithroth – what the fuck do you care?

MITHROTH Very funny, Jack. Always witty is our Jack. Ha ha.

JACK Fortunately – there’s an easy answer….

MITHROTH And that would be?

JACK None of your business.

MITHROTH Ah. Yes, of course. Still, I continue. You and Audrey seem – so it always appeared to me and I have known you both a long long time….

JACK Too long.

MITHROTH What was that, Jack? Yes…. but…. you and Audrey seem more than ever burdened by the breath of experience.

JACK Yes. Good. Not bad. Exactly right.

MITHROTH There is a flavour – a hint – of melancholy. The past as an unbearable burden….

JACK Scars.

MITHROTH Dear O dear. As from the wing no scar the sky retains. So what happens?

JACK She denies it. She denies it but she lies.

MITHROTH puts his hand to his ear.

MITHROTH What was that?

JACK Jesus… what a quagmire.

JACK and MITHROTH are on a street.

JACK My bike is gone. Drat. I’ve had that bike since I was a kid.

MITHROTH throws garbage on the street.

JACK Stop that.

MITHROTH It’s my right. My right and privilege.

JACK It’s always about you, Mithroth….

MITHROTH It’s always me, Jack. Nevermind…. look at this….

MITHROTH points to a boat on a trailer.

MITHROTH Give us a hand. This bloody quixotic thing keeps slipping off. I’ve been at it for a week.

JACK Well the…. hmmmmm?…. we could…. hmmmmmm…. we’ll just wrap this rope around here.

JACK and MITHROTH tie and fuss.

JACK Nice little outboard.

MITHROTH Listen to it sing….

SFX: The outboard engine springs to life.

The boat starts to move.

MITHROTH O look – there’s Audrey. Grab her, will you?

AUDREY I can’t reach.

JACK Lean…. foreword…. more…. more….

AUDREY is hoisted onboard.

AUDREY Have I gained that much weight?

MITHROTH You look trim and lovely.

AUDREY Thanks, dearest.

As if an old habit, AUDREY nuzzles MITHROTH.

AUDREY O look at Jack – Jack loves boats.

JACK Those summers, ya, on Schroon Lake, had a lovely little boat. Five horsepower.

AUDREY (to JACK) You can be so sweet. Look, I’ve got some time – we could be in Paris. We always had a good time in Paris.

JACK Seems a long way.

AUDREY Jack, come on. Jack Jack Jack Jack.

MITHROTH The Bistro Papillon….

AUDREY Or Chez François – I used to go there all the time when I was at the Sorbonne.

MITHROTH Those were salad days. Lovely days.

JACK I love François. He taught me how to cook, you know.

AUDREY I think we all knew that.

They laugh.

JACK O look who’s there. It’s Sandy. (calling) Sandy…. Sandy….

The boat stops.

SANDY Jack. And also Audrey. This is a quality moment.

AUDREY Hello, Sandy. This is The Prince Mithroth.

SANDY O?

MITHROTH Hello.

SANDY Audrey, and prince person, this is Bob.

MITHROTH & AUDREY Bob?

SANDY My baby. Bob the beloved baby Bob. Bob Bob Bobber Bobby Bob Bob Boo. He’s just so new, the dear little thing.

AUDREY We’re going to Paris.

SANDY O they all do at your age. And for the same reasons….

JACK is nuzzling BOB.

JACK O, he’s so sweet. My nephew. My darling little nephew. He looks just like you.

SANDY Really? I though he looked just like Terry.

JACK Actually he looks like Dad.

SANDY I know. I miss Dad.

JACK Me too.

AUDREY is reading a newspaper.

AUDREY Your baby thing is in the newspaper.

SANDY O let me see.

NEWSPAPER (loudly) Desperation! Poverty! Blood! Greed! Death!

AUDREY You know you’re in deep trouble when the newspaper you’re reading starts talking to you.

AUDREY and MITHROTH laugh.

JACK Audrey…. Audrey, come nuzzle Bob, Audrey.

END OF SCENE

•

scene six

Summer evening. A lovely light. Birds chirping. JACK and AUDREY are sitting on their porch.

AUDREY Hot.

JACK Very hot.

AUDREY Much hot.

JACK Hot hot hot.

AUDREY What?

JACK What?

AUDREY What’s that?

JACK What’s what?

AUDREY That.

JACK Where?

AUDREY There.

SFX: Aircraft engines.

AUDREY It’s a plane. A very low plane.

JACK Right, I see it. Much too low. Wait a minute wait a minute – that’s a, that’s a Lancaster bomber. What year is this? They haven’t flown those since that war.

AUDREY They’re circling around, coming back….

JACK O my god….

AUDREY O my god….

JACK O my god….

AUDREY O my god….

SFX: A big crash.

OFF: POOKY starts barking.

AUDREY Who’s got a dog? I hate dogs.

SANDY (off) What’s the emergency number?

AUDREY O my god…. It cartwheeled, O my god….

JACK (calling off) What?

SANDY (off) The emergency number.

JACK (calling off) Nine one one.

SANDY enters, clutching BOB and joins them on the porch.

SANDY Are you sure?

AUDREY It cartwheeled. O my god….

SFX: Sirens in the distance.

JACK Somebody called it already.

SANDY Do you think they’re hurt?

SFX: another explosion

AUDREY O my god.

JACK protects BOB. BOB cries.

JACK O wait. Wait. Wait, there’s somebody.

AUDREY Jack, don’t….

SANDY We should call Terry.

JACK Wait here with Audrey. I’ve got to help….

JACK rushes off.

AUDREY & SANDY (calling off) Be careful, Jack.

AUDREY Bad, very bad.

SANDY Do you think they’re dead?

AUDREY Very very bad.

JACK enters with HUMPHREY and BILL. HUMPHREY wears a bombardier jacket; he has a beard, but only on one side of his face. BILL, very old and frail, is quite natty in a corduroy suit.

JACK They’re alive. There’ll be scars, there’ll be scars for sure.

HUMPHREY What happened?

JACK I’d better see if there’s anyone else.

AUDREY Jack….

JACK exits.

SANDY You crashed on our street.

HUMPHREY I crashed? Who are you?

SANDY I’m Sandy, Jack’s sister.

AUDREY And cartwheeled.

HUMPHREY I cartwheeled? What a mess. I’m so sorry.

SANDY Just as long as you’re OK. And him….

SANDY gestures to the silent BILL.

HUMPHREY Who?

SANDY Him. He looks familiar somehow.

HUMPHREY Never saw the chap before.

SANDY (to BILL) Are you alright?

BILL is silent.

SANDY (to AUDREY) He looks a lot like Jack, do you think?

AUDREY What?

SANDY The same charming bits.

AUDREY Would you, mmmm?, would you – what? – would you like a drink?

HUMPHREY That would be tasty right now. I’d better not – no no, I’d better not – they’ll think I’d been drinking. And I would have been, you see? The manifold pressure just went. Just like that….

HUMPHREY snaps his fingers.

HUMPHREY And what does it mean? What can it all mean? Does it mean anything? Other than death, certain death raining down upon you. I could’ve crashed right on your house, right on you, right down on you. Right straight down right here on you. And you know, I’m not sure I would’ve cared. I’m not sure I would’ve cared at all.

BILL falters.

SANDY (to BILL) Here you’d better sit down. Why does he seem so familiar?

HUMPHREY I’m so happy to be alive.

AUDREY I’m glad. O my…. I’m still so shocked. Are you alight? I’m a doctor.

AUDREY fans herself with her hand.

HUMPHREY You’re so beautiful. You know, I can see your dialogue written right there – right in your eyes.

AUDREY O, everybody can do that.

HUMPHREY I knew you were going to say that.

AUDREY You sure know how to sweet talk a gal.

HUMPHREY There, there, I knew you were going to say that too.

AUDREY What a party. Yikes, I need a drink.

HUMPHREY And I knew that too….

AUDREY exits. BILL starts to follow her.

AUDREY (to BILL) You stay here.

SANDY I’ll take him. He seems just like Jack. Here…. sit sit….

BILL Gazu gazu wabaza. Gazu. Za zu zee. Wugada. Wugada. Toto was wugada. Yabugu dugubu dugada. Gaga zee zu zee za zu.

SANDY What?

JACK enters.

JACK There’s nobody else.

JACK sees BILL.

JACK Wait. O wait wait wait. O my god, Sandy – its Bill, its Bill. Sandy, its Dad.

SANDY Dad?

JACK Dad. Bill…. its me, Jack. And Sandy.

BILL Towns I’ve never heard of but feel as if I do. Or have.

SANDY I thought he seemed familiar. But didn’t he, you know, die?

BILL (singing) I dream of Jeannie with the light brown hair.

SANDY Hi, Dad. This is Bob. Your grandson.

AUDREY enters with a tray.

AUDREY Who wants drinks?

SFX: Loud car crash.

JACK turns, terrified, towards the sound.

END OF SCENE.

TO BLACK.

•

SCENE SET 03 – LOVE LEAVING

scene seven

Early evening. JACK is puttering in his kitchen.

We hear barking offstage.

AUDREY (off) Shut that bloody hound up.

JACK (calling off) We don’t have a bloody hound.

AUDREY (off) Then what the fuck is that?

JACK She’s in a foul quagmire.

JACK pokes about looking for the dog.

JACK (calling off) Its definitely inside.

AUDREY (off) Kill it.

JACK shakes his head. He opens the door to the basement and goes down.

BEAT.

Knocking at the kitchen door.

BEAT.

More knocking. JACK enters from the basement and answers the door. Its the new neighbors – HUMPHREY and NATALIE.

HUMPHREY Hello. Hello. We’re the new neighbors.

JACK Neighbors?

HUMPHREY Right over there.

JACK peers – it’s the house next door.

JACK O yes, right ya, there. The old Crowe place. Hi, I’m Jack.

HUMPHREY I’m Humphrey and this is my wife, Natalie.

JACK Natalie Natalie…. and Humphrey – please come in.

NATALIE We’re not disturbing you?

JACK No. No no no no. I was just thinking about making a supper.

NATALIE Then we are disturbing you.

JACK No no. Mostly all prepped – a little fun cassoulet.

JACK smiles.

Dog barks off.

NATALIE That’s Pooky.

JACK You know that hound?

HUMPHREY It’s our dog. I thought I recognized his happy bark. (calling off) Bark. Bark bark.

POOKY (off) Bark bark.

HUMPHREY (calling off) Bark.

NATALIE (calling) Pooky. Pooky Pooky Pooky….

HUMPHREY (calling off) Bark.

BEAT.

JACK Come, we’ll go look see.

JACK and HUMPHREY exit to the basement.

NATALIE looks about the kitchen.

AUDREY (off) Did you kill the bloody thing?

BEAT.

AUDREY (off) Jack?

NATALIE (calling off) He’ll, he’ll be back in just a minute.

We hear JACK and HUMPHREY fussing in the basement.

HUMPHREY (off) Pooky…. Pooky Pooky….

AUDREY (off) What the hell’s going on?

NATALIE (calling off) I don’t know.

JACK and HUMPHREY enter from the basement.

JACK There’s a tunnel.

NATALIE What?

HUMPHREY Yes, from our place to theirs.

AUDREY enters from upstairs.

AUDREY What the bloody hell is going on?

JACK It’s the bloody new neighbors dropped by for a look see. And guess what?

AUDREY What?

JACK Their dog’s found a tunnel between our houses.

AUDREY A tunnel? A tunnel?

JACK In the furnace room. The hound popped right through it.

NATALIE Clever little Pooky. Such a hero. Is he downstairs? Let’s bring him up.

JACK He’s run back.

HUMPHREY He must been looking for rats.

AUDREY Rats.

AUDREY shudders.

NATALIE Pooky loves rats.

HUMPHREY Rat meat is a delicacy in China, you know.

JACK I heard that. I wonder if if there’s a recipe?

JACK goes to his cookbook library.

AUDREY Jack, I will not live in a house with rats.

JACK Well, Pooky will kill them, dear little beast, and then we can eat them. Hey look at this. (reading) rat with chestnut and duck – this is good. Black pepper rat shoulders hot pot.

JACK looks up, beaming.

JACK This is a whole new thing. (reading) And the ultimate signature tour de force: mushu steamed rat.

AUDREY Fuck the world of culinary delights. I need a drink.

JACK O I think we can manage something for you, darling….

JACK opens a large wooden cabinet – its filled with bottles.

AUDREY All grappa, all the time.

JACK Each a special sweet and succulent kiss – bocchino francoli marolo brunello candolini….

AUDREY It’s Jack’s hobby.

JACK Hard to know what to choose….

AUDREY Serve the drinks for god’s sake, Jack

AUDREY scoffs.

JACK examines a glass; he scowls.

JACK This glass has a scar.

JACK bangs about in the kitchen.

HUMPHREY So, ah…. what is it you do?

AUDREY What the fuck do you care?

HUMPHREY O?….

NATALIE and HUMPHREY whisper and play with their noses.

AUDREY What are you doing?

HUMPHREY Nose calisthenics – we always do them when we feel stressed.

NATALIE You push the tip up and down, back and forth.

AUDREY O god.

NATALIE It’s quite refreshing – let me show you.

NATALIE reaches towards AUDREY’s nose.

AUDREY Don’t touch my nose.

A painful silence.

NATALIE Perhaps it is time we go.

AUDREY Well, if you must.

AUDREY looks into HUMPHREY’s eyes.

AUDREY Wait a minute. I know you.

HUMPHREY You do?

AUDREY Wait a minute wait a minute I know you, I do I do. You’re the pilot. (calling to JACK) He’s the pilot.

JACK Which pilot?

AUDREY The one who crashed on the street.

HUMPHREY Point in fact, I rather liked the neighborhood.

AUDREY laughs delightedly.

HUMPHREY (to JACK) How’s your father?

JACK He’s still dead.

HUMPHREY We all live by such selected fictions.

AUDREY What?

HUMPHREY Shall I explain? I feel I’d like to.

AUDREY And I’d like you to.

SANDY enters.

AUDREY O my god, not now.

JACK Hey, sissy.

SANDY Just popping by.

JACK Is Terry here?

SANDY He’s working on the car. Bob’s helping him.

JACK That’s sweet. Come meet our new neighbors. Humphrey and…. ah…. and…. ah….

NATALIE Natalie.

JACK Natalie. My sister, Sandy. (to SANDY) He’s the pilot.

SANDY is sniffing.

SANDY What’s that? Smoke. I smell smoke.

They all sniff.

HUMPHREY It’s true – smoke.

SANDY looks out the window.

SANDY The house next door is on fire.

HUMPHREY What?

They all rush to the windows.

SANDY Whose house is it? O goodness…. a raging inferno.

HUMPHREY It’s our house.

SANDY What?

HUMPHREY Just moved in, point of fact.

NATALIE Our house is burning.

HUMPHREY and NATALIE exit in a panic.

SANDY Bob? I‘d better go find Terry and Bob.

SANDY exits in a rush.

SFX: Noise, shouting, melee, sirens. The roof collapses.

The room is illuminated as the flames grow larger, flare. Sparks.

AUDREY is overcome.

AUDREY O my god.

JACK puts his arms around her. AUDREY sobs.

JACK So fast.

Disheveled, covered in soot, HUMPHREY and NATALIE return.

NATALIE Horrible horrible…. we’ve lost everything.

HUMPHREY Everything.

JACK Might be a good time for grappa. Ya….

END OF SCENE

•

scene eight

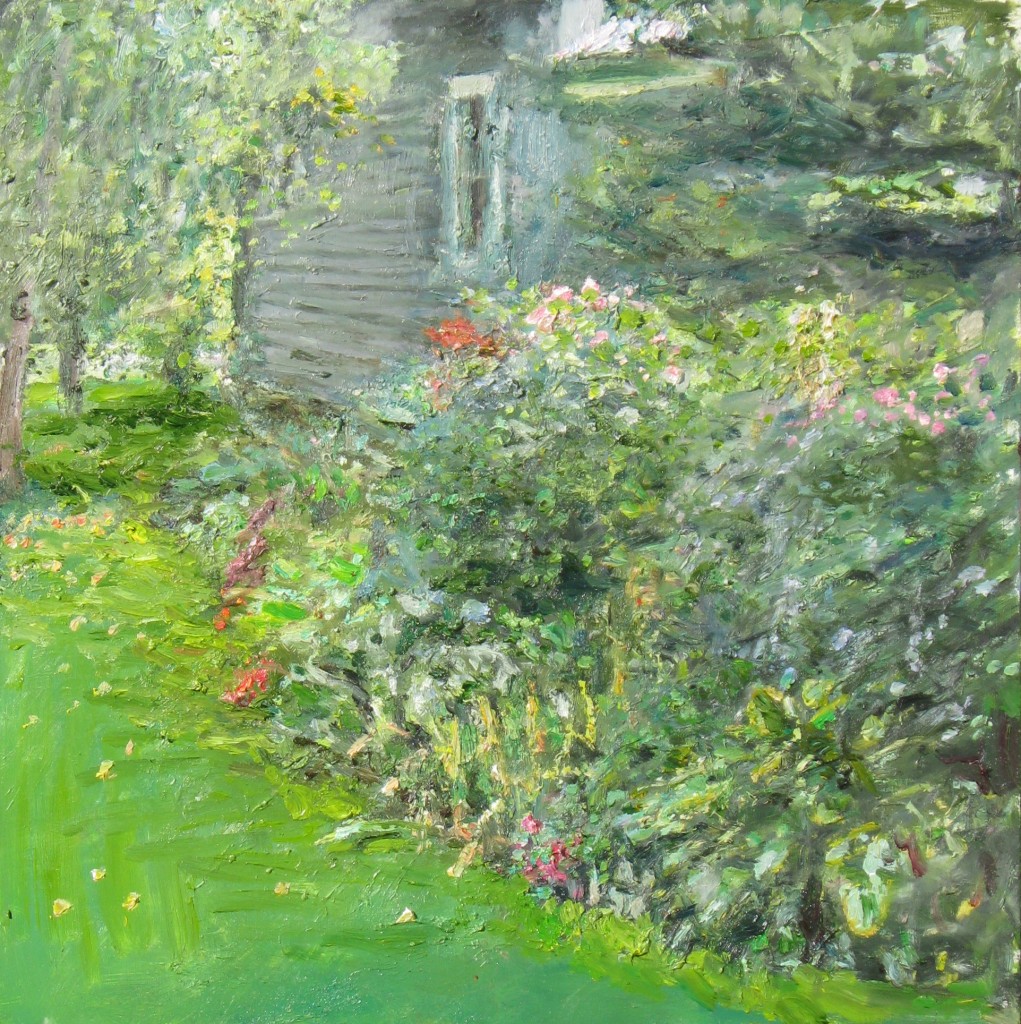

HUMPHREY and AUDREY walk in an art museum. Bright and white. Large canvases of sublime and simple gestures.

A CHORUS sings softly in the background.

HUMPHREY I’ve fallen in love with you.

AUDREY laughs – a ripe Anna Magnani laugh.

HUMPHREY O? I didn’t want to….

AUDREY Thanks for that.

HUMPHREY Yes, but there it is. I love you, Audrey.

AUDREY Maudlin.

HUMPHREY I hope not.

AUDREY Ummmmmmm….

They stand in front of a large canvas. (JACK is the canvas.)

HUMPHREY This one means: kyomu.

AUDREY Did you say: kyomu?

HUMPHREY Nothingness. The Japanese have four hundred words for it.

AUDREY Really? That many?

HUMPHREY It seems necessary

AUDREY Well, we have ten thousand words for: dysfunctional human endeavor including body parts so I guess I understand.

HUMPHREY Give me an example.

AUDREY O? Almost anything. Oufffff. Ah…. good intentions, loyalty, betrayal, killed with a kissing knife, love….

HUMPHREY That’s very complex. You are very complex.

AUDREY I find it comforting.

HUMPHREY You’re smashing. That means: attractive.

They move to another canvas.

AUDREY This one has a faded quality…. more attractive than the last, anyway….

HUMPHREY Yes, I suppose.

AUDREY (imitating HUMPHREY) Yes, I suppose. (normal) You always seem reticent to commit yourself.

HUMPHREY Do I? I said I loved you.

AUDREY Do you say it to Natalie?

HUMPHREY Do you say it to Jack?

AUDREY Shush.

HUMPHREY Now you seem reticent.

AUDREY So? And?

HUMPHREY Yes yes yes. That’s it. Right. Exactly. You are so attractive. More than that. Beautiful. Its why I love you.

AUDREY You don’t love me. You don’t know me.

HUMPHREY I want to. Would you like to sit? You seem to be limping.

They sit.

HUMPHREY What’s, what’s this bandage?

AUDREY This old thing? I cut myself.

HUMPHREY How?

AUDREY Stupid.

HUMPHREY Me?

AUDREY No, me.

AUDREY takes out her penknife.

AUDREY With this.

HUMPHREY Whittling again, were you? O, there’s a scar. Is it serious?

AUDREY O, for god’s sake, I am a doctor. I should be working now – I cancelled a surgery for this, you know.

HUMPHREY gets down on his knees; he kisses the bandage.

AUDREY Stop that.

HUMPHREY I want to make it better.

AUDREY Thank you. Now, get up.

HUMPHREY Tell me something….

AUDREY Well, I love you too.

HUMPHREY makes a face.

AUDREY What?

HUMPHREY “I love you too” is passive. “I love you” is active.

AUDREY So?

HUMPHREY More attractive.

AUDREY I…. I don’t want to be attractive.

HUMPHREY Alive and in the moment? A strong core? Compassionate above all? It seems good.

AUDREY Hmmmmm? What I want to be – alright I’ll tell you: fragile as paper, bold as the north wind. The Queen of all the demons.

HUMPHREY Well, I think you’ve succeeded admirably. And then some.

AUDREY Can I tell you what I really want? – intimacy and…. vulnerability. Can you offer me that?

HUMPHREY What about Jack?

AUDREY I never found Jack attractive. No intimacy with Jack, no vulnerability.

HUMPHREY But love?

AUDREY Of a sort. Some sort. I don’t know. I don’t want to be with Jack. He brings out the worst in me.

HUMPHREY Why did you marry?

AUDREY Stupid.

HUMPHREY Me?

AUDREY This time – yes. At the start, who knows anything?

HUMPHREY I loved Natalie from the start.

AUDREY You keep bringing her up. Don’t. And don’t underestimate Jack, just because he seems like nothing.

HUMPHREY He does, doesn’t he. Very kyomu.

AUDREY Ha. Jack was a great chef. His restaurant was always packed. Always. Three stars, all of that. He gave it up.

HUMPHREY Why?

AUDREY A long story. An old story. Our story, more interesting to me now. Nevermind Jack. What’s the one single thing you would change in your life if you could?

HUMPHREY I’d have you as my wife.

AUDREY That’s sweet. Me, I wish I could have more – a bigger dollop – of the kindness gene.

JACK, the painting, sighs.

HUMPHREY The kindness gene?….

HUMPHREY laughs.

AUDREY Well, I don’t have it.

HUMPHREY Are you kind to your patients?

AUDREY Am I kind to them? I take care of their problems as best I can. Some of them survive. Is that kindness? I don’t think so.

HUMPHREY Do you mean “nice”?

AUDREY snorts.

AUDREY Do you think I’m nice?

AUDREY throws apples at HUMPHREY. She laughs – full throated and sexy.

HUMPHREY Hey, stop that.

AUDREY See?

HUMPHREY Jesus, what a bloody thing.

AUDREY laughs and poses.

HUMPHREY You are impressive.

HUMPHREY gives AUDREY a brass chain with a medallion attached.

AUDREY What’s this?

AUDREY reads the medallion.

AUDREY (reading) The fear of everything is love.

HUMPHREY Put it on.

AUDREY I don’t think so.

HUMPHREY Please.

AUDREY No.

JACK, the canvas, falls off the wall.

END OF SCENE

•

scene nine

Evening. JACK and AUDREY in Chez Zuzu, a restaurant. They’ve finished dining, and wend their way to the coatcheck.

JACK Goulash? What’s suddenly so wrong with goulash? Chez Zuzu makes the best goulash in the accessible world. Fluffy, it is.

AUDREY What?

JACK Jesus, boys, I wish my goulash was that fluffy.

AUDREY O stop it.

AUDREY burps; JACK chuckles.

At the cloakroom. DELORES is helping SHLOMO on with his coat.

SHLOMO Thank you, thank you very much. You are very kind. Very kind.

SHLOMO smiles at JACK as he exits.

SHLOMO Good yom tov, good yom tov….

JACK I know him. I’m sure I know him. God, I can’t remember where. Or when. I feel so disoriented. I’m leaving my coat.

AUDREY What?

JACK I’m leaving my coat.

AUDREY snorts.

AUDREY I’m taking mine.

AUDREY hands the ticket to DELORES (She doesn’t notice DELORES).

JACK It’s not that cold out.

AUDREY It’s bloody winter.

JACK I don’t want to be dragging it around all night.

DELORES So what are you saying, Jack – you don’t want your coat?

AUDREY Delores?

DELORES Audrey?

AUDREY What are you doing here?

DELORES Making ends meet. So…. Jack, you want your coat?

JACK No, I’m leaving it for the evening.

DELORES That’s real dumb.

JACK Shut up.

DELORES You shut up.

JACK Or what? You’ll take me down?

DELORES I don’t want any trouble, Jack.

AUDREY So what are you saying?: I don’t pay you enough?

DELORES No one is ever paid enough.

AUDREY I could pay you more.

DELORES But would you?

JACK Hey, handle that coat carefully – do you hear me? – its cashmere.

DELORES sighs.

DELORES I don’t want any trouble, Jack – my hands are tied. If the coat stays, you pay.

JACK More money?

DELORES It’s all about money, Jack.

JACK God, that’s depressing.

DELORES It’s the way it works.

AUDREY You are crazy.

DELORES (to AUDREY) Who?

JACK Alright alright alright.

DELORES A hundred and twenty-seven dollars.

JACK A hundred and twenty-seven? Jesus, I could buy another coat for that.

DELORES The price would be optimistic, if you wished (imitating JACK) genuine cashmere.

AUDREY laughs.

JACK Please don’t laugh.

AUDREY Don’t tell me what to do.

JACK (to DELORES) What time do you close?

SANDY enters.

SANDY Jack.

JACK Hey, sissy. Did you have the goulash? Good, eh?

SANDY I’m a vegetarian now.

AUDREY laughs.

JACK (to AUDREY) Please don’t laugh.

SANDY Have you seen Terry?

AUDREY Not in a rat’s age.

SANDY Is that a no?

JACK Ha.

SANDY Anyway, I think he’s in the can puking his guts out. Hey I had a nice chat with Dad today.

JACK Dad?

SANDY He sounded great. Well, you know Dad.

AUDREY But he’s dead.

SANDY shrugs.

JACK Where’s Bob?

SANDY He’s on the table.

JACK peers.

SANDY See you….

SANDY exits.

AUDREY Your sister gets on my nerves.

AUDREY rolls her eyes.

JACK Do not roll your eyes at me. I will not be diminished. Look at that, look at that.

AUDREY What?

JACK She’s dragging my coat on the floor. (calling) Stop that. Delores, stop that.

DELORES Don’t do anything, Jack…. please don’t do anything.

AUDREY Jack, take your bloody fucking coat and let’s go.

JACK I don’t want to take my coat.

AUDREY You’re driving me crazy.

DELORES Is it my turn yet?

JACK laughs.

AUDREY (to DELORES) Its embarrassing to me that you’re here. I only do what I can. We have fun.

DELORES snorts.

AUDREY We do. We laugh

DELORES You laugh – I laugh with you

JACK Is nobody listening to me? Drat.

DELORES (to AUDREY) You used to give more.

JACK (crow-like) Caw kraa caw. Caw. Caw.

AUDREY (calf-like) Mmuuh möö. Möö.

JACK (crow-like) Caw. Caw.

AUDREY (calf-like) Möö. Mmuuh.

JACK (crow-like) Kraa.

These two speeches together:

AUDREY (calf-like) Möö. Möö. Möö. Möö. Mmuuuuuuuuuuuh.

JACK (crow-like) Caw. Caw. Caw. Caw. Caw. Caw. Kraaaaaaaaaaaaaaa.

BEAT.

JACK I can’t do this anymore.

AUDREY What?

JACK Möö möö caw caw möööööö caaaaaaaw. That.

AUDREY You’re crazy.

JACK Be that as it may.

HORST comes over.

HORST Is there a problem here?

JACK You’re fucking right there is. Nobody’s listening to me: I resent being diminished. That coupled with a general pervasive debilitating sense of disorientation. I’d say that was a problem – wouldn’t you?

HORST I’m generally not interested – generally – in your problems.

DELORES laughs.

JACK Who are you? Wait. Wait. I know you. See? This is exactly what I’m saying.

AUDREY You’re raving.

JACK Again? What a quagmire.

DELORES I know these people, boss – they’re trouble. Scary trouble.

JACK All scarred up and nowhere to go.

DELORES whispers in HORST’s ear.

HORST O? (to AUDREY & JACK) I presume you’ve come to dine….

AUDREY We’ve already eaten. It was very fluffy.

AUDREY laughs.

JACK It was.

HORST Good. So now you wish to retrieve your coat?

JACK No, I wish to leave it here.

HORST O I see, a joke. Very funny.

HORST does something very very frightening.

JACK Jesus, stop that. You’re scaring me.

HORST Yes, exactly.

DELORES laughs.

JACK I want merely to continue leaving my coat here – and later – at some other moment – to retrieve it.

AUDREY Take the bloody coat. Let’s just go.

JACK (to HORST) You render me speechless – as you’ll all agree: a rare occurrence. Would that generally register as a concern with you?

HORST Perhaps. Perhaps not.

JACK And your sudden and imminent death?

HORST Perhaps. Perhaps not.

AUDREY Jack! You’re mad.

JACK O, I’m sorry, was I speaking out loud?

HORST Delores, give this gentleman his coat and the freedom of the street.

JACK (to AUDREY) Do you love me now?

END OF SCENE.

•

scene ten

AUDREY’s office. AUDREY is examining HUMPHREY. He is wearing a split hospital gown.

Bending over the examination table, AUDREY is looking up HUMPHREY’s rectum with a flashlight. She is wearing the medallion he gave her in the previous scene.

Meanwhile, outside the frame, a watching JACK….

AUDREY Bend a little lower please. Lower….

HUMPHREY Is this good. Ow.

AUDREY’S robust laugh.

AUDREY Just relax. Lower please…. O?

HUMPHREY Is it bad?

AUDREY Very complex.

HUMPHREY Is that bad?

As AUDREY pokes and prods, the medallion catches in his rectum.

AUDREY Oops.

HUMPHREY Ow.

AUDREY Watch a minute….

HUMPHREY Ow ow ow….

AUDREY Don’t move – the bloody medallion’s gotten stuck….

HUMPHREY I gave you that medallion.

AUDREY Well, I’m taking it back….

She pulls the medallion out.

CHORUS SFX (Pop).

AUDREY There.

The watching JACK suddenly exits only to immediately reappear. A ruckus, as JACK breaks in, with DELORES on his back.

JACK Stop hitting me.

DELORES You can’t come in here.

JACK You’re always blocking the door.

DELORES That’s my job, honey.

JACK Don’t you dare “honey” me.

AUDREY Jack?

HUMPHREY tries to hide his semi-nakedness.

JACK I have to talk to you.

DELORES I could take you down. I could take you down right now.

JACK I really really doubt it.

AUDREY Jack….

JACK We have to talk.

AUDREY At home? Later?

JACK Ha ha. That’s cute. You’re never home. Never. And I know you’re having an affair – a dreary word and a dreary world, the two – with him.

HUMPHREY What?

JACK (to HUMPHREY) Don’t dare deny it, you sleazy shitey scumbag. All protests are futile.

DELORES That’s crazy talk.

JACK Sad sad sad. I’m having a bad year and even singing doesn’t work anymore. And meanwhile you’re doing what with this – tacky tacky tacky – this….

JACK sneers.

JACK This…. person.

HUMPHREY I am a person.

JACK Shit up your ass. Ha. (to AUDREY) Admit it. Admit it admit it admit it.

AUDREY and HUMPHREY, a long look. Is it true?

JACK (to DELORES) What are you looking at?

DELORES Shut up.

JACK You shut up.

DELORES You shut up.

JACK Ha.

DELORES I’m taking you down. Right now.

JACK and DELORES fight.

SFX: More crashes and bangs.

DELORES renders JACK immobile.

JACK (to DELORES) Brute.

JACK picks himself up.

JACK Jesus, my head hurts. Please, please O don’t concern yourself – I’m alright, Jack. Whatever happened to kindness?

MITHROTH enters.

AUDREY & DELORES & HUMPHREY The Prince Mithroth.

JACK Drat. Fucking Mithroth.

MITHROTH O, Jack…. I am only myself.

A vulnerable AUDREY goes to MITHROTH.

AUDREY Daddy, I’m having such a hard time

MITHROTH There, there, I’m here now.

JACK (to MITHROTH) Why is it you’re everywhere I look?….

JACK pirouettes.

JACK He’s always here? Its Paris all over again. Its never stopped, never stopped. You two living together….

MITHROTH In Paris, Jack? Do you mean in Paris? Merely friends sharing a kitchen.

JACK And a bedroom.

MITHROTH Two bedrooms.

JACK Scars.

MITHROTH I am a Prince, Jack – and a virgin as well. If that’s any consolation….

JACK Aversion?

JACK’s pun is ignored by all.

JACK Nevermind this. You want to know something? It turns out I had had a dream. So what Audrey just said to me was just exactly what I had dreamt. Amazing? It goes on. Finally, naturally, we’re in a fussy mood, she and I and self-inflict damage on ourselves.

DELORES Audrey is fabulous. Fabulous.

AUDREY smiles winningly at DELORES.

DELORES Jack is nothing. Washed up has-been. Not just my opinion – her’s too.

JACK (to AUDREY) Is that true?

AUDREY nods.

JACK Blood. Misery. Pain. Degradation. Humiliation. Misery – O I said that already.

MITHROTH I am so so sorry it has all come to this impasse. A pity. It was better at the beginning. I need more delectable and delicious detail.

JACK No.

MITHROTH Please, Jack, please please please. Please please please please….

JACK (to AUDREY) This has to be told. (to MITHROTH) Audrey slashes her ankle. I stick my blade into my arm – lucky me, I hit an artery. The paramedic is forthcoming and less than sympathetic. You stupid stupid people, she said. I had to agree. Scar poxed.

DELORES This is all wrong. He’s telling the story wrong.

JACK You weren’t there.

DELORES If I had been, I’d have taken you down.

JACK But you weren’t there, were you? And you didn’t, did you? You know what? It’ll never be as good again. I remember you when you were less…. unkind. We used to be friends, you and I. (to MITHROTH) Anyway, enough detail?

MITHROTH Not bad. You know, Jack, I’ve come to think despite all your ravings – this has to be said – I suspect you know nothing of truth.

JACK Ya? When I look into your eyes I can see what you’re going to say next.

MITHROTH What?

JACK I can see your dialogue written right there. (as MITHROTH) You mean – what do you mean?

MITHROTH You mean – what do you mean?

AUDREY I am having an affair with Humphrey.

JACK Aha.

AUDREY I love him.

HUMPHREY You do?

AUDREY Madly.

HUMPHREY I’m so so…. moved. You dear sweet person.

AUDREY You dear sweet person.

HUMPHREY O, I say.

JACK What confused consternated crap. What is it?

AUDREY Humphrey is sensitive.

JACK I’m sensitive.

AUDREY He’s considerate.

JACK I’m considerate.

AUDREY He’s caring.

JACK I’m caring.

AUDREY He’s passionate.

JACK This is stupid. Don’t, for god sake, don’t. Don’t do this. Why? Tell me that at least. Stay. I’ll cook only Italian all the time. Just Italian. Classic mezzogiorno. No more experiments.

AUDREY I hate your cooking.

MITHROTH Never explain, Audrey.

JACK is beside himself.

JACK I’ll get lawyers. You’ll wish you’d never been born.

AUDREY I already do.

JACK sighs.

AUDREY We wanted too much of each other

JACK But that’s what love is. That’s exactly what love is. Its a whole package…. That’s it, a whole package. A whole bloody package. What a quagmire.

JACK silently leaves.

END OF SCENE.

•

scene eleven

AUDREY’s office. A discrete collection of model Eiffel Towers. AUDREY stands, contemplating a large medical drawing, a cutaway of a rectum.

JACK enters.

AUDREY Jack.

JACK Audrey.

AUDREY How surprising to see you.

JACK Why not?

AUDREY Why not indeed.

JACK looks at the medical drawing.

JACK Interesting….

AUDREY A trifling post-conceptual rendering.

JACK But large.

AUDREY Yes. So goes the scale, so goes the mind.

JACK looks out the window.

JACK I feel so disoriented – I’ve lost my way – the town seems different somehow.

AUDREY Demonstrate, please.

JACK More mountains. And more scars on said mountains. Drat. And why is this? I am distressed, again anxious. A veritable quagmire.

AUDREY Poor dear thing.

JACK picks up an Eiffel model.

JACK This one?

AUDREY Yes?

JACK I believe it was the first.

AUDREY Was it?

JACK Yes. Bought on the Boulevard Saint-Jacques.

AUDREY The day François promoted you to souschef.

JACK Yes. We had such a lovely time.

AUDREY In Paris?

JACK Yes.

AUDREY Yes. My work at the Sorbonne. Life was powerful then.

JACK Yes. Now sad.

AUDREY Why?

JACK I will not be diminished by anything less that the truth. I wish to be loved.

AUDREY You dear mad thing.

JACK I will hardly accept such rendering of my fragile social persona.

AUDREY is wearing the HUMPHREY medallion; JACK notices it.

JACK What is that, pray tell?

AUDREY What, dearest?

JACK That medallion – I do not recall it.

AUDREY This? It’s nothing.

JACK O?

JACK sighs.

JACK I know you don’t love me anymore – what am I to do?

SFX: Loud car crash.

JACK turns, terrified, towards the sound.

Suddenly, AUDREY is in great pain. She clutches her midriff.

JACK What’s this? What’s this?

AUDREY Pain.

JACK Digestion?

AUDREY Not. A possibility has been suggested by The Prince Mithroth…. I wish you liked The Prince Mithroth.

JACK His diagnosis, please.

AUDREY Inflamed gall bladder.

JACK Where is this gall bladder? Demonstrate please.

AUDREY Attached to the liver.

JACK How dark and confusing.

AUDREY There. There…. its passed.

JACK Good. Still….

AUDREY What?

JACK Dust, nothing but dust.

AUDREY How nice – you remember Mr Eliot. I must, I must go. A surgery to perform.

AUDREY exits.

JACK weeps.

JACK Bitter tears

SANDY appears, carrying a swaddled BOB.

SANDY You did good, Jack. You stood up to her.

JACK I will not be diminished, Sandy.

SANDY I know. Here, hold Bob.

JACK nuzzles Bob.

JACK I love this.

SANDY It’s Terry’s favourite thing too.

JACK You think I did good?

SANDY nods.

JACK Then why do I feel so bad? Poor me, poor me, ever the jealous brooder. A sink full of wet socks. What to do but wring them out and hang them to dry? Spilling the lentils. The sound of it. O fuck, I say. Well, wouldn’t you?

SANDY Jack. Dear Jack. Jack Jack Jack – I know I would.

JACK smiles.

JACK Would you?

SANDY Of course.

JACK, a sigh, a moan.

JACK I’m fading fast, sissy. Dear Jack says you, poor Jack says I, but, hey, a life definitely on the wane. O man. O man. I go to her office, I confront her, I express my pain. All the time I’ve wasted. Always Audrey. (as AUDREY) After all these years, Jack, you poor slob, what can be left between us? (as HIMSELF) Always Audrey. Only Audrey.

JACK, a small sob. BOB joins in. SANDY tries to take BOB – JACK gently but firmly holds onto the child.

JACK (to BOB) You dear little thing.

JACK looks at BOB; hugs him.

JACK (to SANDY) And I am, yes I am a poor slob – and that’s what’s left and that’s the very point. It’ll never be as good again, Sandy. Never. A package of shite. That’s it, that’s it exactly…. a package of shite.

BEAT.

JACK Drat.

END OF ACT

TO BLACK

•

ACT TWO

SCENE SET 04 – DARKNESS AND BLACKNESS

scene twelve

A prison camp. JACK, AUDREY and HUMPHREY in the yard. Is it raining? Or just a mean and bitter drizzle?

HORST, the commandant, and CURLY, a soldier, enter.

CURLY Attention, attention prisoners. Line up for inspection. Now now now – you can do better than that mealy slugged-faced fucking moronic shit for brains beasts of the rectum fucking shites.

JACK groans.

AUDREY Shush.

HORST (to HUMPHREY) You.

HUMPHREY Yes, Doctor.

HORST (to HUMPHREY) Your personal hygiene is disgusting.

HUMPHREY Yes, Doctor.

HORST No food for this man for two days.

CURLY Sir.

HORST (to JACK) You. I don’t like the glint in your eyes.

JACK Ha.

CURLY What?

HORST Beat this man.

AUDREY No, Doctor, don’t.

HORST What?

JACK What she means is – ah….

HORST What?

JACK I know what – there’s been a small error.

HORST An error?

AUDREY We shouldn’t actually be here.

CURLY laughs.

HORST (to CURLY) Shut up.

CURLY Sir.

HORST indicates AUDREY’s medallion.

HORST What is that?

HORST tears the medallion from her neck.

AUDREY Ow….

HORST (reading) The fear of everything is love.

HORST scoffs.

HORST I don’t think so. Pathetic.

HORST slaps AUDREY.

HORST No, less than pathetic – pathetic would be an achievement for you.

HORST spits in AUDREY’s face.

HORST Where did you get this?

AUDREY He gave it to me.

HORST indicates JACK.

HORST This one?

AUDREY indicates HUMPHREY.

AUDREY No…. him.

HORST No food – three days.

CURLY Sir.

AUDREY We are not the people you think we are.

HORST No? Aha….

AUDREY We’re Audrey and Jack.

JACK Harmless.

AUDREY Perfectly harmless.

JACK A smidge complicated.

AUDREY But who isn’t.

HUMPHREY That’s so very interesting. I was thinking that very same thing earlier today. Your hospitality, Doctor, allows me much and plenty time to think. I’ve discovered my life isn’t always what I thought it was. Can you believe it?

HORST Beat this man.

CURLY beats HUMPHREY.

JACK I hate this.

AUDREY Shush.

JACK And there’s always new people – everywhere I look I see new people – and I don’t know them and I don’t want to know them. Does that make me a bad person?

AUDREY If only we could get a message to The Prince Mithroth.

JACK I can’t bear this anymore. I feel so disoriented. I can’t wait, I don’t want to wait, I’d rather die. Drat. This, this is a quagmire.

The sun is large as it suddenly sets. Very large. Very stunning.

HORST and CURLY turn to admire the setting sun; they are captivated by the sight.

HORST Beautiful, simply beautiful.

CURLY So so beautiful.

JACK Here’s our chance to escape.

HUMPHREY Take me with you.

BABY JACK appears.

BABY JACK And me. Please take me – please – if you would be so gracious and forever kind.

JACK It’s Baby Jack.

BABY JACK How are you, my dear benevolent generous sir.

JACK (to HUMPHREY) Scoop up the kid and let’s boot it.

HUMPHREY scoops up little BABY JACK; they run fast and far. Eventually they are on a city street.

AUDREY Which way should we go?

JACK I don’t know. I don’t know this place. I feel so disoriented.

HUMPHREY I’m going to wait at that bus stop.

BABY JACK A most excellent plan; I agree completely.

AUDREY Bus stop?

HUMPHREY The two of us, we’ll just blend right in. What could be more natural than a man and a baby?

AUDREY A bad idea.

JACK Very bad.

BABY JACK We simply don’t concur – surely a most reasonable product of discourse? – and that is that. A pity but regrets, ah yes, regrets, I’ve had some few. Still, one must go on….

HUMPHREY The bus stop is a perfectly sensible idea.

AUDREY Jack, do something.

JACK shrugs.

Suddenly a truck screeching to a halt. SFX: truck breaks, noisy.

JACK and AUDREY hide behind a potted plant.

CURLY and HORST jump out. HUMPHREY panics, drops BABY JACK, and runs.

CURLY Hey, stop. Stop.

HORST Nevermind – kill him.

SFX: Machine gun fire.

CURLY shoots the fleeing HUMPHREY who falls horribly dead.

AUDREY & JACK O my god.

BABY JACK And me? What of me? What of poor dear little innocent me? Am I to die in the street as if a impoverished persecuted plague ridden god-forsaken rodent?

HORST (to CURLY) This one, this one I want to keep.

AUDREY & JACK O my god.

JACK and AUDREY turn and run.

JACK Which way?

AUDREY What about those woods?

JACK Where?

AUDREY There.

JACK O you are clever.

AUDREY Act natural.

JACK O ya, like I’m feeling really natural.

AUDREY Let’s not run.

JACK But I want to run.

AUDREY Put your arm around me.

JACK I’ve forgotten how.

AUDREY Shush….

JACK and AUDREY reach the woods and hide.

JACK O my god – look.

HORST is lurking about at the fringes of the woods.

JACK This was a stupid place to hide.

AUDREY O ya, right – and we had a whole lot of choice.

JACK Paris would’ve been a better choice.

AUDREY smiles.

AUDREY Shush….

HORST is just in front of JACK and AUDREY – he doesn’t see them.

JACK jumps out and tackles HORST. They struggle.

HORST You…. will regret…. this….

JACK Audrey…. Audrey…. kick him in the balls.

AUDREY Jack, what a horrible thought.

JACK O I’m sorry, was I speaking out loud?

AUDREY laughs as she attacks HORST. HORST falls back, gasping in pain. JACK kills him with a large rock.

JACK Wow….

JACK falls over.

AUDREY Jack, what’s wrong?

JACK He cut me. Here….

JACK points to his thigh.

JACK Is it bad?

AUDREY Pretty bad.

JACK Drat, disorientation suddenly seems a nothing problem compared to this.

AUDREY Rest.

JACK You are kind to me

AUDREY No I’m not. Now be quiet.

JACK Tell me a story.

AUDREY Do you remember when we met?

JACK No. Yes. No.

JACK winces in pain.

AUDREY At that party. After finals. You came up to me and said: you’re the only one here I don’t know.

JACK I did, didn’t I?

AUDREY And then we spent the night under the dining room table.

JACK Ya.

AUDREY So many years ago.

JACK A lifetime ago.

AUDREY I’ve never loved anyone else.

AUDREY & JACK (singing softly) Clang, clang, clang went the trolley

Ding, ding, ding went the bell

Zing, zing, zing went my heartstrings

From the moment I saw you I fell….

CURLY enters.

CURLY (calling off) Where’s the Commandant?

ANOTHER SOLDIER (off) I saw him go into the woods.

CURLY (calling) Hello…. Hello…. (calling off) Cover me….

CURLY enters the woods.

CURLY Hey, I see them….

JACK covers his face as explosions firestorms shrapnel as well as general impaling and uncontrollable spasms engulf the stage.

END OF SCENE.

•

scene thirteen

JACK’s kitchen. Early morning – the sun is just about coming up.

JACK enters, carrying a goldfish bowl.

The lights go out.

JACK Drat – what happened to the lights?

JACK, flashlight in hand, looks about the kitchen.

The kitchen is filled with various and many goldfish bowls; some of the fish are quite large though this may be a distortion due to the extreme curvature of the glass.

JACK (shouting) We have to protect the fish from the cat. If we had a cat….

Suddenly JACK rushes to gently pick up a fish.

JACK How did this get here?

A tear from JACK. Is it still alive?

AUDREY enters, dressed in a power suit.

AUDREY What happens?

JACK I don’t know.

JACK puts the fish in the water – it floats on the top.

AUDREY Dead?

JACK I don’t think so. O wait – its mouth is moving.

AUDREY Ha.

JACK looks at AUDREY – a pained look.

AUDREY Good. Well, I’m off.

AUDREY exits.

JACK (quietly) Will you be home for dinner?

SFX: A slashing whirling noise off.

AUDREY laughs, off.

JACK What?

AUDREY (off) You’re going to want to deal with this.

In a flap and a flurry, JACK exits to the garden. One of the salient features: layers of giant hedges. HORST and CURLY are cutting and slashing the hedges.

JACK Excuse me.

BEAT.

JACK (shouting) Excuse me.

BEAT.

JACK (shouting) Hey….

CURLY and HORST stop.

JACK What the fuck?

HORST Please refrain from foul language, sir.

JACK I’ll say exactly what I fucking well want to.

HORST I would advise you not.

HORST advances on JACK.

JACK This is my property. I advise you to shove your tongue up you rectum.

CURLY What did he say?

HORST I won’t repeat it.

CURLY Hey, was that the wife? What a peach.

JACK is aghast; he is about to speak when SANDY enters (pulling BOB behind her in a little red wagon).

SANDY What are they doing, Jack?

JACK Just a minute – wait – I don’t know.

HORST These types of hedges, they’ll be trouble latter on.

CURLY Lovely specimens….

HORST But frankly planted too close.

CURLY Much too close together.

HORST Later this will be a problem.

CURLY A big problem.

HORST You’ll thank us for this.

CURLY They always do.

HORST You’ll thank us.

CURLY And you’ll pay us.

SANDY What should we do?

JACK shakes his head.

SANDY A hedge as old as the hills. Ugly, now. Pity….

CURLY It needed to be done.

SANDY We should do something. Should we call Audrey?

JACK No god no.

HORST and CURLY laugh and laugh.

SANDY We should do something.

JACK Stop stop stop stop what you’re doing.

CURLY Or what?

JACK pulls out his penknife.

JACK Or this.

HORST and CURLY laugh, the tears steaming down their faces.

SANDY Wait a minute. Terry has something better.

SANDY exits, with BOB.

HORST Is that the knife she stabbed you with?

JACK Who?

HORST and CURLY laugh.

CURLY That Audrey person.

JACK No.

HORST Its not what we heard.

JACK I stabbed myself. Jesus….

CURLY While we’re talking we’re still on the clock.

HORST Paid by the hour.

JACK Not by me.

HORST Every second of your life that passes is gone – lost – forever.

CURLY The bill keeps getting bigger and bigger.

HORST An understanding will be required.

JACK Go. Go away. I don’t like you.

CURLY Boo hoo.

HORST Someone named The Prince Mithroth asked us to do this.

CURLY Or maybe it was the wife, eh?

JACK groans.

HORST You know this said The Prince Mithroth, do you, sir?

CURLY He told us to do this job.

HORST Then he run away.

CURLY He run far away.

HORST He run away into the night.

CURLY The deepest darkest night.

HORST Run run run run run away.

JACK I’m…. I’m I’m….

HORST sneers.

SANDY enters with a massive automatic weapon. A bazooka?

CURLY and HORST laugh.

SANDY I’ll take care of this, Jack. Stand back….

HORST More trouble, eh, Curly.

CURLY Always trouble, Horst.

HORST It follows us wherever we go.

SANDY cocks the weapon.

JACK O for god’s sake, Sandy, be careful.

HORST Yes, be careful, little woman.

SANDY Get out. Now.

SFX: SANDY fires off a burst.

CURLY The woman’s crazy.

HORST But I like her style.

CURLY We’re not finished.

HORST Not even close.

CURLY First, we’re going to do the work here.

HORST Then we’re going to do this little woman’s house.

CURLY Take it right down to the ground?

HORST That’s it – take it right down to the ground.

CURLY I’d like that. I’d really like that. I’d really really really really really like that.

HORST And then let’s crush that little baby Bob while we’re at it.

CURLY Ya, Let’s get rid of that Bob.

CURLY & HORST Oink oink oink.

CURLY and HORST laugh.

SANDY Take that…. and that….

SANDY shoots CURLY and HORST. SFX: Many gunshots. CURLY and HORST scream and fall dead. A messy affair.

SANDY You did good, Jack. You stood up to them.

JACK I don’t know.

SANDY You’re a brave man, Jack.

JACK I suppose….

SANDY I love you for it.

Police sirens in the distance.

SANDY Ugly, now. Poor hedge.

The lights come on.

JACK O, the power’s back.

The lights go out.

JACK Drat. What happened to the lights?

SFX: Loud car crash.

JACK turns, terrified, towards the sound.

END OF SCENE.

TO BLACK.

•

SCENE SET 05 – THE DEATH OF AUDREY

scene fourteen

JACK (off) Forget it, just forget it, Sandy.

Daytime. JACK’s large sunny kitchen. A large collection of colourful Eiffel Tower models squirreled here and there.

Bowls of goldfish – there are many such now in the kitchen.

JACK enters with a goldfish bowl. He puts down the bowl, opens a window and yells outside.

JACK (calling off) OK, I’m listening.

SANDY (off) Terry took the message.

JACK (calling off) What did she want? Her freedom?

SANDY (off) The message was: no message.

BOB cries.

SANDY (off) There there, you dear little piggy poo.

JACK & SANDY Oink oink.

JACK (calling off) Is she coming back, you dear old thing?

SANDY (off) O I’m sure I don’t know, you dear old thing. That’s too complicated for me. (singing) I will not languish.

JACK joins her.

JACK & SANDY (singing) I will not laaaaaaang-guish.

BOB joins in.

JACK (calling off) Just a minute, just a minute…. when did Terry take the message?

SANDY (off) Was there a message?….

JACK (calling off) Just a minute….

JACK exits outside.

BEAT.

AUDREY enters with a few suitcases and a large package.

BEAT.

JACK enters with goldfish.

JACK Ah. You. Well. Well well – this is a surprise.

AUDREY Look what I brought you.

JACK For me?

JACK opens the package – it’s a very large skillet.

JACK O? And will it fit on the cooktop?

AUDREY I wonder….

JACK gets into the skillet. He washes the salad greens. AUDREY laughs her big laugh.

AUDREY What are you doing?

JACK I’m making a salad for dinys.

AUDREY Like that?

JACK I always make my salads like this.

JACK sighs.

JACK When I do anything. Mostly nothing I do nothing.

AUDREY O what are you talking about?

JACK And where have you been? You used to live here. Its all running down. To nothing much. Drat. What if its all like…. like a bloody uncooked haggis. I will not be diminished. (doing a Scottish voice) You lie to me, you lie to me all the time.

AUDREY O my god, you sound just like my father.

JACK (Scottish voice) You’ve been gone for months. Or is it days? I might have wanted to go with you.

AUDREY There’s my freedom to consider.

JACK Freedom…. freedom. There’s a punchline to that…. I forget it. Drat. O I remember – you used to be honest. I loved you for it. Now the crow may be singing instead of the calf.

AUDREY O shut up. If you’re looking for a reason, honey, this is it.

JACK Don’t call me “honey” if you don’t mean it.

AUDREY snorts.

JACK You used to….

AUDREY What now?

JACK Mean it. I felt that anyway.

AUDREY You used to be someone who wasn’t knock kneed crazy.

JACK O stop it. Look – my opinion….

AUDREY scoffs.

JACK Wait wait, I’m having an idea….

JACK picks up an Eiffel Tower.

JACK My opinion: Paris was a package.

AUDREY What?

JACK We were all together, of a thing, you and I and the rue Rivoli. And the metro and Chez François and everything. Every breath was a laugh.

AUDREY I don’t remember it like that.

JACK At least a chuckle? Work with me. Even fucking Mithroth had it right. Salad days. Lovely days. Paris was a package – that’s why we loved it. Its all about Paris. And the package, the whole package. That’s it – the whole package, you got to take the whole package. That’s it that’s it. There’s no substitution. The whole package. No. No no. No no no no. Don’t say anything – hear me out. I’ll lose my thread. Its like at a country auction. You bid a box, you bid on a box – its a lot. You bid on a lot – three bucks – and you take the whole box – lock stock and box. That’s it, mama. You have to take the whole package.

AUDREY I hated Paris.

JACK How could you? Paris was kindness.

AUDREY wavers, uncertain on her feet.

AUDREY What do you mean? Kindness? What do you mean?

JACK Kindness? Its the opposite of – what? – fear. What, what are you afraid of? It all started in Paris. Don’t you remember?

AUDREY I was never in Paris.

JACK The scar capital of France?….

AUDREY laughs. Suddenly, she collapses, blood dripping from the corner of her mouth.

JACK What? What?

JACK takes AUDREY in his arms.

AUDREY mumbles.

AUDREY Kindness….

JACK What?

AUDREY All those times I said I loved you…. all those times…. was I lying?

BEAT.

AUDREY You should’ve be kinder.

JACK Me? You, you’ve never been kind enough. No no, I can’t do this anymore.

AUDREY Dear O dear, its too late.

JACK It’s never too late.

AUDREY I think I meant it.

JACK About love?

AUDREY Or did I?

AUDREY dies.

SFX: Car crash, far in the distance.

JACK is in shock; he feeds the fish.

END OF SCENE

TO BLACK

•

SCENE SET 06 – LIVING ALONE

scene fifteen

JACK is standing in the foyer of a large art museum. We see a sign: THE LIFE OF AUDREY.

HUMPHREY and NATALIE enter. JACK rubs his hands gleefully.

JACK Humphrey and Natalie, thanks so much for coming by. I wanted you to be the first to see the exhibition.

NATALIE It’s not open yet?

JACK Not yet. Soon, though, and a jovial time it’ll be – I’m already having a good time.

HUMPHREY Well then I’m honoured. We both are….

JACK I thought it was important you see it. Give me your opinion….

NATALIE I’m sure we’ll love it – just as we loved Audrey.

JACK Thank you. (to HUMPHREY) You’ve been here before, haven’t you?

HUMPHREY Here? Yes, of course. An important art museum, this.

JACK Yes, I thought you’d say that. Come….

They enter the first room. Large photographs of a young AUDREY.

NATALIE O, she’s so young.

HUMPHREY Is it all arranged chronologically?

JACK It might be.