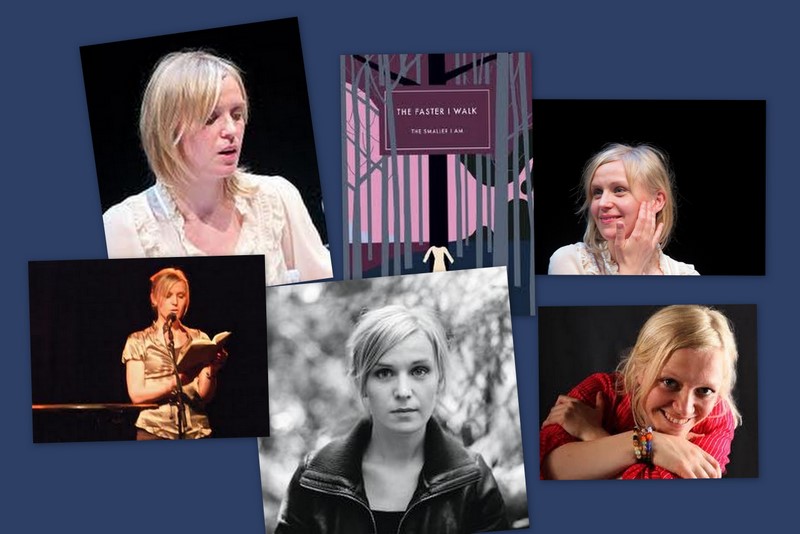

Kate Reuther

Kate Reuther

.

A MAN WALKS INTO A BAR. He orders a beer and tries to pay with a five-dollar bill.

“You can’t use that here,” the bartender says.

“Why not?” the man says.

“Because this is a singles bar.”

“Very funny,” the man says, reaching for the glass.

*

A man walks into a bar. He sits down next to a blonde with a Pomeranian dog on the next stool. The man waves at the bartender who keeps polishing the taps.

“Does your dog bite?” the man asks.

“Never,” the blonde answers.

The man reaches out to pet the dog and the dog bites him. Hard.

“I thought you said your dog doesn’t bite!” the man says, wrapping his hand in a dirty dishtowel.

“He doesn’t,” the blonde replies. “That isn’t my dog.”

The man kicks the counter so the pint glasses ring. “Can I get a fucking beer over here?”

*

A man walks into a bar with a slab of asphalt under his arm. He places the asphalt on the stool beside him and flexes his red, ragged hands.

“What’ll it be?” the bartender says.

“A beer please, and one for the road.”

The bartender’s eyes flick to the clock on the wall.

“What?” the man says. “You’re not open?”

“I thought you were back at work,” the bartender says.

“I’m on break,” the man says. “Jesus, you’re worse than my wife.”

“Just take it easy today,” the bartender says, plunking down two frosty bottles.

“Yes, dear,” the man says.

*

A man walks into a bar and orders twelve shots of tequila.

“Go home, man,” the bartender says. “Your wife’s been calling every fifteen minutes.”

“I said twelve shots!” the man repeats. “Line ‘em up!”

The bartender starts pouring and the man pounds them as fast as he can. He doesn’t even taste the tequila anymore, although his eyes begin to water.

“Maybe you should slow down,” the bartender says. Most days he would argue that a man’s life is his own to do with as he pleases, but in this case there is the crying wife. Pregnant too. “Let me call you a cab.”

The man sways and knocks back another shot. “You’d be drinking too if you had what I have.”

“What’s that?” the bartender asks. Suffering follows this man like a hungry dog.

The man slurps the twelfth, amber glass. “Fifty cents.”

*

A man walks into a bar carrying a duck.

“Get that pig out of here!” the bartender shouts.

“It’s not a pig, you idiot!” the man replies. He staggers a little, although he’s only had two or three. The problem is the duck, which is surprisingly heavy.

The bartender reaches for the baseball bat under the counter. “I was talking to the duck.”

“I think we better go,” the duck says.

“I’ve got money today,” the man says, fumbling for his wallet. He splays it open with his free left hand. “Twenty bucks.”

The bartender grabs the wallet from the man’s outstretched fingers, extracts the Jackson, and tosses it back empty. The duck catches it in his beak.

“I’m gonna be nice and say this covers the mess you made last night,” the bartender says.

“But what about now?” the man says. “Just one beer?”

“Get the fuck out of here, pig,” the bartender says, patting the bat against his palm.

“Did you see that?” the man shouts. The other bar patrons stare decisively at their coasters. “He robbed me. You’re all witnesses!”

“Let’s just go,” the duck says through a mouthful of leather.

*

A man walks into a bar and orders a beer. It’s early, quiet — the air still smells of fresh Lysol over old piss.

“Nice shirt,” a voice chirps to his right.

The man turns, ready to bark that it’s a uniform, that he has to wear it or the manager will dock his pay, and a man’s got to earn for his wife and future child, even if it requires stuffing his gut into a lime-green Cellular Circus polo, but then he realizes there’s no one else sitting at the bar. He’s alone with the dishwasher-hot glasses and the fresh bowl of peanuts.

The man takes a long swig from his beer. He holds the cool bottle against his forehead.

“Nice pants,” the voice says.

The man swivels around on his stool, making the metal shriek. He looks left and right, behind him, under the seat, in back of the bar, but the only other customer, a giraffe, is busy feeding quarters into the cigarette dispenser. The man reaches for his beer with a shaking hand.

“Nice shoes,” the voice says.

“Shit,” the man says, knocking over his beer. The puddle rushes towards the edge of the bar and dribbles onto the man’s shoes, which are, in fact, cheap, imitation-leather penny-loafers, minus the pennies. When he takes them off at night, his socks are sweat-wet and brown.

“Everything all right?” the bartender says, coming over with a dirty towel.

“There’s this voice,” the man whispers. “It keeps making comments about my appearance.”

“Oh, that’s the nuts,” the bartender says, gesturing towards the plastic dish. “They’re complimentary.”

“Shit, if I wanted to talk to nuts, I could do that at home,” the man says.

“We were just trying to be nice,” the nuts say.

“So you were lying?” the man says. “You don’t like my shirt?” He grabs a handful from the bowl. The salt stings the cuts on his palms.

“It’s a very bright green,” the nuts say.

The man raises his fist towards his open mouth.

“Please,” the nuts say. “Don’t.”

“Say something nice about my teeth,” the man says, crunching the nuts between his molars. “Tell me about my beautiful tongue.”

*

A man walks into a bar with an alligator under his arm. Or rather, he tucks the spiky tail under his arm and drags the heavy, gray body behind him.

“Do you. . . . do you serve lawyers here?” the man asks. He can’t catch his breath. He misses the asphalt and the duck which, compared to the alligator, were light, compact, and good conversationalists. Maybe he can devise a harness for transporting the alligator. Maybe he can borrow the stroller until the baby is born.

“I’m sorry, man, but you’ll have to leave,” the bartender says. “Jacket and tie required.”

“Jacket and tie?” the man says. “Since when?”

“Since always,” the bartender says, hooking a thumb at a party of tuxedoed chickens shooting pool. A red hen makes a tough bank shot and the chickens cluck appreciatively.

“I’ll be right back,” the man says, heading for the door.

The alligator hisses.

“Hey, you can’t leave that lyin’ there!” the bartender says, but the man is already crossing the road. He rips open the door of his station wagon and dives into the backseat, hideously festooned with Cellular Circus coupons, empty beer cans, penguins, moldy sandwiches, newts, tinfoil, and ragged pieces of string. Finally he finds the jumper cables, tangled around the ribcage of a lawyer’s skeleton.

The man walks back into the bar, the jumper cables looped around his neck. The alligator is lurking underneath the pool table amidst a spray of white feathers.

“Do you serve lawyers here?” the man asks the bartender again. One of the metal claws on the jumper cables is crusty with battery acid. The man wonders what would happen if he licked it.

“I’m good,” the alligator mumbles.

“Shut up,” the man says. “I wasn’t talking to you.” He was only supposed to stop for one drink, then he could still be home early, like he promised his wife. Right about now she’ll be setting out the placemats, whisking some sauce with orange peel or capers, sweating and humming and rushing around in their little shit-brown kitchen where none of the cabinets close all the way. He’ll be late, maybe just a little, but then he’ll trip over the welcome mat, and she’ll start crying. A Niagara Falls of tears and him in the barrel. The man will take her in his tired arms and tell her what she wants to hear: that he’s finally got the drinking out of his system, that he’s ready to come home early, to put together the crib, to throw his dirty clothes in the hamper, to help her choose a baby name. And his wife will sigh and mash her face into his lime-green chest, anointing his shoulder with her slippery snot. He can bear her weeping but not her forgiveness.

The alligator belches.

The bartender looks the man up and down – his waxy shoes, his bandaged hands, his dirty polo, his neck hung low by dirty cables. Rumor has it that Cellular Circus finally fired him after he came back from “lunch break” and tried to lick a lesbian Eskimo.

“You can have one drink,” the bartender declares, setting a glass under the tap, “but don’t start anything.”

“Why would you say that?” the man asks. “I’m one of your best customers.”

The phone behind the bar rings.

“I’m not here,” the man says. “You haven’t seen me.”

*

A man walks into a bar carrying a goldfish, a parrot, a baby kangaroo, and a fifteen-inch pianist. The bar is loud and crowded, with a rabbi, a priest, and a nun reenacting the highlights from their softball victory, a party of polar bears blowing their bonuses on top-shelf single malt, and Shakespeare’s here tonight, punching hair-metal songs into the jukebox.

The man shouts, “Can I get a…” but then his feet slip out from under him and he smacks down on his tailbone in an unseen puddle of vomit. The goldfish, the parrot, the baby kangaroo, and the fifteen-inch pianist go flying.

“Can somebody give me a hand?” the man says, struggling to his knees, but no one moves. The man is bad luck, they agree, the type who will eventually insult a tribe of hungry cannibals, or leap from a plane wearing a book-bag instead of a parachute, and even if he survives there is the matter of the weeping wife, who still loves him despite the lies and debt and the moldering-liver smell.

“A beer,” the man says, finally heaving himself onto an empty stool. His soggy pants squelch against the cracked leather. “Keep ‘em coming.”

The bartender, a pony, coughs and pours.

“Busy tonight?” the man asks, squeezing his trembling hands together as in prayer.

The pony nods his extensive face but does not reply, only stares at the floor with wet eyes. The man knows he ought to inquire as to the pony’s sadness, but he really isn’t interested, besieged as he is by his own problems, and what’s more, there is a fresh beer sitting before him. The man drinks.

“Water,” the goldfish gasps from underneath a stool.

Each sip of beer is a reprieve, the jaggedness made smooth, the broken made whole again. The man wants to be a better man, and three sips into his beer he can see the possibility of change: first thing in the morning, a new résumé, then a new job. He’ll clean out his car, buy salad greens and yogurt, replace the Brita filter, fix the kitchen cabinet doors. He’ll even change the way he talks to his wife. It’s important, when the baby comes, that their voices be soft, tender, with rounded corners.

There is a knock at the door.

The bar patrons look up from their drinks, confused, because the door isn’t locked, is it?

“Honey?” calls a voice from outside. “Are you in there?”

The man hunches his shoulders and ducks his head, a humiliated gargoyle.

“Sweetheart?” she says again. “Baby, it’s me.”

The man grinds his teeth on the edge of his glass. Why is his wife here? He’s not even late yet, not very. And now the rabbi, the priest, and the nun have put down their mitts and are staring at him with those sanctimonious eyes. It’s only a beer. A man should be allowed to have one beer, to relax a little with his friends. His wife is so absolutist about everything. A more reasonable solution would be to cut back, to limit his drinking to one or two a night, except for special occasions. She can’t really expect him to stop entirely, can she? With all that he’s carrying?

Knock-knock.

His wife moves away from the bar door and begins pacing in front of the frosted window, shadow arms cradling a shadow basketball-belly. “Have a little faith in me,” the man always says, and she does, she still does. She has faith that her husband is going to come striding out of that bar any minute now. “Just settling my tab,” he’ll say. “These roses are for you.”

The pony coughs.

“You sick?” the parrot asks, extracting a cigarette from an abandoned pack.

The pony shakes his head. “No, I’m just….”

Hinge-squeals cut through the bartender’s answer as the door swings open. The man closes his eyes. He feels the blood rising in his neck, like hot rain in a clogged gutter. If only he could stab himself with a fork, cut off his head with a guillotine, anything rather than face this humiliation.

The bar is silent except for someone’s slow jingling steps.

The man opens his eyes. It is not his wife; it is a cowboy. The cowboy is so muscular, he cannot rest his arms at his sides; they perch like mug handles above the painful shine of his belt buckle.

“Howdy,” the cowboy says. But suddenly he is falling, his boots skidding left then right then up, like a newborn colt, and finally the seat of his hard-creased blue jeans lands in the vomit puddle.

“I just did that,” the man says, smiling for once. His misery may not love company, but it does enjoy her rare moments of attention.

The cowboy stands. He picks his hat off the floor. He removes a piece of partially digested carrot from the brim and places the hat back on his head. Then he grabs the man by his polo collar and tosses him against the side of the pool table.

“No, wait,” the man says, “you got the wrong idea…”

The cowboy does not wait. He cocks his alligator boot and releases it into the man’s stomach. The cowboy kicks him carefully, methodically, stepping back between blows to gauge the distance and effect. The man feels the rotten apple that is his body crumble and break. It does not hurt. Not yet. What bothers him is the bar patrons’ unwillingness to help. Where are the friends who say, “Break it up, break it up,” who wedge between the fighters like spatulas?

Knock-knock.

Kick. Kick.

“Have mercy,” the man croaks. “I’ve got a family.”

The cowboy spits, grabs the man by the ankles, and begins swinging his body in a circle like a hammer. This room has spun for the man many times before, but never so quickly. It is beautiful, almost, the kaleidoscope of gold taps, turquoise feathers, white fur, black habit, waxed wood, window shadows, and glass. The man’s loafers slip off. The air cools his wet socks.

The cowboy lets go and the man arcs through space, an Olympic record surely, if not for the light bulb above the pool table, which his head shatters, and then the less permeable jukebox. On impact, it whines, shudders, and begins playing Cinderella’s “Don’t Know What You Got (‘Till It’s Gone).”

“Honey?” his wife says from outside the door.

The man is bloody, shattered, and thirsty. He cries. He is a man who walks into bars. A nothing. A drunk.

“Hey,” the pony says, “why the long face?”

The bar patrons begin to laugh. The fifteen-inch pianist gasps and wheezes and clutches his gut. The cowboy stamps his foot so hard his spurs ring. Shakespeare pees in his pants a little. The goldfish, dead, does not laugh. But the rest of them, once they’ve started, cannot quit their rhythmic, vocalized, expiratory and involuntary actions.

“Stop it,” the man says.

They don’t stop. They laugh harder.

Twenty-five chuckling Polacks march in from the back room, all carrying a single stepladder. They approach the broken light bulb.

“Darling, come home,” his wife pleads and pounds.

The baby kangaroo snarfs his beer.

“It’s not funny!” the man cries. “It’s not funny at all.”

—Kate Reuther

.

Kate Reuther‘s fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in The Madison Review, Brain Child, Salamander, and The Ledge. She is a graduate of Yale and the Vermont College MFA in Fiction program. A life-long New Yorker, she lives in Washington Heights with her husband and two boys.

Laura Catherine Brown’s first novel, Quickening, was published by Random House Inc. in 2000. Her shorter pieces have appeared in two anthologies, Before: The Big Book on Parenting, from Overlook Press and The Bigger the Better the Tighter the Sweater with Seal Press. In addition to being a writer of fiction, Laura taught creative writing as an adjunct professor at Manhattanville College for over two years. She has been earning a living as a graphic designer since 1990 when she received her B.F.A. at the School of Visual Arts. She is also a dedicated yoga instructor and practitioner, having studied a variety of styles and traditions of Hatha Yoga for over twenty years.

Laura Catherine Brown’s first novel, Quickening, was published by Random House Inc. in 2000. Her shorter pieces have appeared in two anthologies, Before: The Big Book on Parenting, from Overlook Press and The Bigger the Better the Tighter the Sweater with Seal Press. In addition to being a writer of fiction, Laura taught creative writing as an adjunct professor at Manhattanville College for over two years. She has been earning a living as a graphic designer since 1990 when she received her B.F.A. at the School of Visual Arts. She is also a dedicated yoga instructor and practitioner, having studied a variety of styles and traditions of Hatha Yoga for over twenty years.