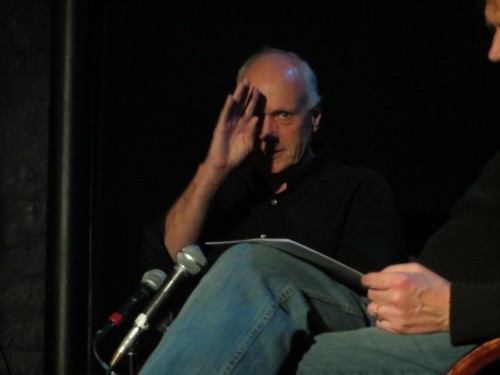

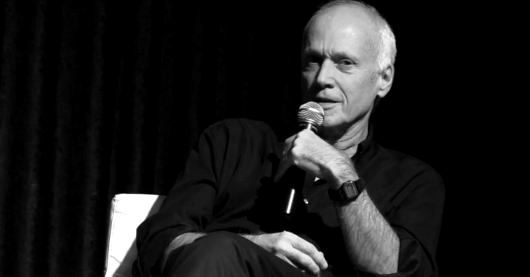

Here’s the Theatre Passe Muraille onstage interview with Douglas Glover, who wrote the book (Elle) on which the stage play (Elle) by Severn Thompson is based. Andy McKim, artistic director at TPM, is a really intelligent and genial interlocutor (there were three pages of lovely questions of which he only managed to ask a handful). The event was billed as “Eggrolls with Andy” and there were, in fact, eggrolls. This was on the evening of January 20, just before the main performance. The location is the little cabaret stage in the bar on the balcony above the stage at TPM. The pictures were taken by the poet Amber Homeniuk, who has appeared before on these pages. She managed to capture some of dg’s more expressive moments.

The sound file is below the images.

I almost missed this one from yesterday. Actually, a good review of Severn Thompson’s performance. Here’s a teaser. Click the link below for the rest.

Severn Thompson, who adapted the play from the original novel by Douglas Glover and plays the role of Elle, is absolutely captivating. In what is essentially a one-woman show, minus about ten minutes, Thompson holds the audience’s attention in a vice grip with her precision, depth and hilarity. Her script it beautifully poetic, and she is a master of its delivery. Through her words and conviction, she creates a landscape and characters that were as vivid and clear as if they had been on stage with her.

Read the rest at Mooney on theatre.

Another review. This one at Torontoist. Here’s a taste:

For a full-blooded heroine with courage, resourcefulness, and a healthy libido to match any debauched Victorian gentleman, look no further than Elle at Theatre Passe Muraille. Actress-playwright Severn Thompson’s rousing adaptation of Douglas Glover’s 2003 novel finds her embodying the legendary Marguerite de La Rocque de Roberval, the young French aristocrat who was marooned on the fabled Isle of Demons off the coast of Newfoundland in 1542 and lived to tell the tale.

Glover’s conception of Marguerite is of a “headstrong girl”—and a bawdy one, too. When we first meet her, she’s aboard her uncle’s ship, having vigorous sex with her seasick tennis-player boyfriend as a means of distracting herself from a horrendous toothache. It’s one helluva’ opening scene—hilarious, erotic, and disgusting all at the same time.

Read the rest at Torontoist.

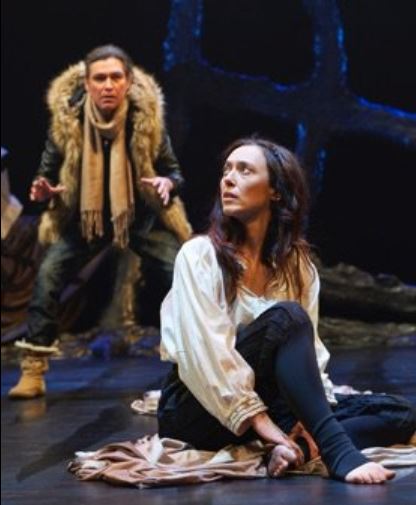

Severn Thompson as Elle, and the sheet (see below)

Severn Thompson as Elle, and the sheet (see below)

State the obvious. Elle, the novel, and Elle, the play, are distinct works of art. They are radically different forms; we have different expectations. The novel’s more than 200 pages of text suck down to perhaps 40-45 pages of script. This is necessary for the transformation into a play, a necessity and a problem for the playwright in terms of selection, but it’s not something the novelist mourns because, of course, the novel remains, fully in tact, over there on the book shelf.

In brute terms, a lot of the novel disappears. What disappears? The whole sequence of events that occurs after Elle’s return to France is gone. That means Rabelais is gone and the joke about Elle inventing the modern novel. Comes Winter, the native girl brought to France by Jacques Cartier, also disappears. Her tragic story is a dystopian inversion of Elle’s own adventure in Canada. Also gone is the frame device of the one-eyed child-stealing man and the novel’s contemporary tail with the Elle-like young woman on the beach at Sept-Iles with her older lover. These characters and devices are meant to extend the myth and the story of Elle into a larger, more mysterious cosmic rhythm beyond history. The novel is built around a complex set of themes loosely implied in words and oppositions like transformation, literary/orality, translation, New World/Land of the Dead, the invention of printing, colonization/love, and so on. Very little of this survives in the play except in stray phrases or references. Also missing from the play are the details of Roberval’s own failed colony upriver from Elle, pages and pages reduced to a few phrases and the mention of the colony’s failure. What survives in the play is a reduced set of events, a roughly similar sequence of action from Elle’s arrival in Canada to her rescue and departure for France and then, of course, Roberval’s murder in a Paris cemetery years later. The play focuses on Elle’s time in Canada and, in plot terms, becomes more of a female adventure story, Elle as Robinson Crusoe, than the novel is. Conversely, also in brute terms, a lot of the text of the play, the words, come straight from the novel. If you imagine a Venn diagram of the novel and the play, they would overlap at these points. After that, they diverge.

I say this not to diminish the play but to be clear about differences. You don’t want to make the mistake of expecting the play to replicate the novel precisely. I have listed some of the novel elements that didn’t make it into the play, but Severn Thompson’s Elle is an enactment, a presence, with a different structure and tool set, different intentions. It has actors, set, sound, lighting and a reactive audience, all in the same three-dimensional space. A novel is pure text; a play has a physicality that bleeds into the plastic arts so that on stage, moment by moment, you’re presented with tableaux or pictures that have a physical beauty. The presentation at Theatre Passe Muraille has an amazing set, starting with the what the director Christine Brubaker calls “the claw,” a metal and papier mache structure at the back of the stage that looks like the ribs of shipwreck or a dead animal or the back of a cave or the edge of a forest. It also feels like a hand, cradling the characters on the stage in front of it. This is the magic of theatre. The claw is an abstraction that changes with light, verbal context, character action, and, above all, the audience’s imagination.

Besides the claw, there’s the sheet. Oh, wonder of abstraction and efficiency. Severn and Christine needed a bear onstage and a woman changing into a bear and a way to imply that the actors are entering the world of dream. If this were a movie, there would be an actual bear. The sheet is a miraculous rectangle of cloth of indeterminate but changing colour that seems stretchy and drops into gorgeous folds. It’s a sail, Richard falling into the ocean, a robe, a tent, a flag, a hut, a fire, a bear, a sign of dream, and the face of transformation when Elle changes into a bear. There are some stunning moments with this sheet, which is sometimes on the stage floor, sometimes woven into the arms of the claw, sometimes suspended on hooks over the stage, and so on. When the white bear falls upon Elle and dies, it’s the sheet. It’s eerie how quickly the audience gets the implication, a lovely bit of theatre and timing. When the bear woman cures Elle and she drifts into a dream state, Severn the actress has her arms inside the sheet which, pulled from behind by Jonathan Fisher, the second actor on stage, creates a stunning abstract idea of a woman with golden wings. And, of course, when Elle changes into a bear, she’s draped in the sheet, again pulled from behind, so that the human face is suggested but is also bearish. She changes into a bear just by having the sheet pulled against her face and body.

There is deliberate anachronism in the play just as there is in the novel but enacted quite differently. Itslk is an Inuit hunter in Elle, the novel. He presents the intersection of European colonization and the myth/culture of native Canada. In the play, his role is expanded. Jonathan Fisher has a desk and sound board and a microphone and a guitar set up off to one side of the stage. Through the play he makes music, sings a native song, does a throat singing loop, plays the guitar, etc. He’s a contemporary native artist/musician watching the play and participating in the play and, at the appropriate moment, he comes to the centre of the stage and plays the part of Itslk. Again, theatre is physical. In the same moment, Elle is onstage speaking her lines (having sex with Richard, pleading with her uncle, crooning over her dying baby) AND the contemporary native is present just a few feet to the side with an electric guitar and a soundboard. The effect in a theatre is difficult to parse precisely because, in the audience, you are aware of the juxtaposition but at any given moment the imagination is engaged with Elle or the line. The lighting focuses you. It’s a mechanism of audience manipulation that seems marvelous to me. And, of course, there are multiple message loops: Jonathan Fisher is an actor but also an Anishinaabe musician. Also in real life he is a member of the bear clan. And he delivers one of the lines that does depart significantly from the thematics of the novel. This occurs when he is reciting the story of his mythic quest/hunt for the white bear, a quest that Elle disrupts by her presence (one of the crucial metaphors of the novel is the moment when Elle’s European story collides with Itslk’s mythic quest and destroys it). In the novel Itslk is aware, sadly and tragically, that the disruption of his story means the ultimate disruption of his culture, a moment that cannot be redeemed. In the play, Severn Thompson gives Jonathan’s Itslk a more hopeful line about the bear returning, the myth world coming back (in other words), which is a nod to the contemporary resurgence of native of culture. The novel wants the reader to dwell in sadness; the play wants to leave some hope. That aside, there is clear a moment of delight when Itslk appears. You can feel the audience shift. It’s a daring and brilliant invention, this Jonathan Fisher/Itslk character. And he gets to deliver some very funny lines, bring back the dead dog, bring back the tennis ball, and deliver the thematic legend. (It’s fascinating watching audience, BTW. When Elle throws the ball off the ship and Leon, the dog, apparently dies, the audience turns against her, faces go suddenly glum. But when we hear the dog bark off stage, glimmerings of recognition appear. And there is a wondrous delight when Itslk produces the lost tennis ball — for me, this is a bit like watching the readers reading my novel.)

Lighting, sound. You deeply enjoy the effects. The framing of the tableaux on stage and with lighting creates a monumental feeling, creates focus, creates shadow and transformation. Some images are spectacular. For example, the moment when Elle/Severn falls through the ice. Suddenly she’s illuminated by a bright filtered light from above, a column of light, that imitates the flickering, shadowy feel of being under water while the actress mimes a person drifting down. There is more of this than I can describe here. And in all these moments you see the differences in the kinds of works of art. Novel. Play. (And film, if you think about it — the play is so much a series of abstractions demanding audience interaction whereas in a movie there would be much more of the real, a real ship, a real island, a real bear. A film more often than not will try to leave less to the imagination than a play or a novel.)

A play has actors, not to be left out. Severn Thompson loved the novel Elle and saw a place for herself in it, and she is a spectacular actress. On stage every fibre of muscle is engaged in action. Her body is an instrument. She is amazing to watch. We are so used to movie and TV acting, which is mostly minimalist acting from the eyebrows to the chin (actually, on TV acting is mostly a minimal movement of the lips in speaking). The intensity of a stage play is astonishing. I saw three performances and the best audience was the third night which had an ASL component and a large number of deaf people in the audience. ASL is, of course, an enactment of language. Deaf people communicate with actions and they are acutely tuned into the physicality, the presence of the speaker. You could almost feel their attentiveness to Severn’s every move. In stature, she is a diminutive woman; on stage she is monumental and heroic (also very comic, sometimes pathetic, always passionate, exploding with energy). The lighting keeps trapping the gestures, like a series of still photographs, and they are gorgeously expressive. She’s also just a wonderful mime. With a gesture and a hanging of the head, she inhabits bearishness. She knows how a body looks drifting in the ocean. She has so much to work with in the play from lust (gorgeously funny sex scene early on, also a scene in the novel), rapture, resignation, pathos, rage, animal transformation, flirtation, and love to childbirth and the death of the child. It’s a huge part for an actress, a dream role, I would think. And Severn runs with it. Extravagantly and joyfully. I wrote the book, and I was still misting up when Emmanuel dies in her arms. Even the third time I saw it.

What else? Too much to think of. A note on structure. The novel has some little thematic pre-texts, then the frame with the one-eyed man, then the sex scene on shipboard. What the play does instead is quite fascinating. It actually opens with what you might call an overture, a montage of moments (tableaux accompanied by gong-like sound effects and flashes of light) that in fact presage the action of the whole play in gesture alone. The bear is the there, the death of the general, the death of the baby. Just a gorgeous piece of structure. Then the frame: Elle in Paris, by the cemetery, catching sight of the general, Roberval, her uncle in the gloomy street and starting to tell her story. Then the story begins, on shipboard, sex with Richard. Fleetingly, Elle steps back into the storytelling moment, once or twice, just enough to establish the frame and story together, and then we are off. We return to the frame scene at the very end of the play (these transitions beautifully indicated by a repetition of gesture, key language, also a slight costume change and a jug of wine) and thence to the final confrontation with Roberval. Throughout there are beautiful recursions, language, shape and gesture. The “headstrong girl” phrase from the novel. The shape and presence of bearishness (even Jonathan Fisher, with his fur vest, sometimes hulks like a bear). The cradling of the baby Emmanuel (at one point, again, Fisher is back behind the claw, apparently cradling a baby in his arms). It’s also interesting the way the play is text heavy through the scenes up to and including the arrival of Itslk. When he leaves and after the birth and death of the baby, the play leans more and more heavily on image. Itslk’s presence effectively introduces the native element and begins to educate Elle in the epic traditions of the new world (she is already steeped in her own epic traditions). The death of the baby and the advent of the bear woman (and her symbolic rebirth in the ocean) bring Elle into the world of dream and dream and image subsequently drive the remainder of the play, which, here, takes on a quality reminiscent of German Expressionist theatre. These are structural effects, small and large, that you notice upon revisiting the play, and you begin to appreciate the amazing physical inventiveness of theatre.

When I go to a play, I desire a total experience: intelligent interaction with characters/actors on the stage, magical and surprising effects, emotional engagement, language. I got what I wanted when I saw Severn Thompson at Theatre Passe Muraille. I wrote the book, I knew the lines, but I was still surprised and entranced. It was delightful still on the second and third viewing; I saw more, of course, and appreciated the artistry more (and was able to peek at the audience). If you can, go more than once. It’s revelatory. First reviews of the play kept mentioning that awful movie The Revenant (which, in my head, I keep referring to as The Ruminant). That is a completely wrong-headed response based on the most superficial resemblances (wilderness, survival, bear, revenge). Elle (both play and novel) is about first contact, the tremendous collision of European and native cultures, it is about an act that is continuous and ongoing, a conversation between our cultures. Because she is a woman (and a reader), Elle is the most apt and available of the Europeans for transformation. She and Itslk are paired cultural receptors; they know what is going on, the vast, tragic pageant. The Ruminant is a movie with its dumbed-down realism and a pop-Nietzschean thematic that’s very appealing to commercial audiences. It’s not the same thing at all.

—dg

Saw the play for the last time last night then closed the Epicure with Jonathan Fisher, the excellent Anishinaabe actor who plays Itslk, with audience members coming up to the table and chatting to us. A most pleasant way to pass the time.

Here’s another review, somewhat more thoughtful and appreciative of Severn as an actress.

dg

The virtue of Glover’s novel and of Thompson’s adaptation is its satire. When Elle is rescued she notes that Portuguese and Basque fishermen have been coming to Canada long before the French “discovered” it and claimed it for their own. That Elle survives longer in the wilderness than the French government-supported colony is itself a critique of colonists’ inability to adapt and learn from their surroundings. In its anti-male satire, Elle may call herself “frivolous” but her tennis-playing lover is hopelessly impractical and is the first to die. In ints religious satire, Elle, once a fervent Catholic, begins praying to both her god and the natives’ and finally to none.

The role that Elle provides is a juicy one for Thompson and ideally suited to her strengths. Her wry delivery makes the satire all the more trenchant. Her ability to convey a character’s strength beneath her own view of herself as vulnerable is perfect for Elle’s situation. Thompson has always been an insightful interpreter of words, but here she has a chance to display her equally superlative skills at mime and physical theatre. The Elle she creates changes before us from a self-centred society-oriented aristocrat to simply a lone human being with the one simple wish to survive.

Jonathan Fisher, who primarily adds live guitar music to Lyon Smith’s highly effective soundscape, is a taciturn, self-contained Itslk, welcome as an unromanticized First Nations character. His presence in what it otherwise a one-woman show is important for embodying the show’s critique against the European colonization of the New World as if it were not already inhabited. Physically, the playing area already is inhabited before Elle becomes aware of it.

Designer Jennifer Goodman has reconfigured Theatre Passe Muraille’s Mainspace into a narrow thrust stage bringing Thompson very close to the audience, the peninsular stage helping to depict both the isolation of the ship and later the isolation of the island. Goodman’s set is a giant bony structure that looks very much like the skeleton of left hand or left paw threatening those on stage. Yet, depending on the lighting, it can also look like the inside of the cave where Elle seeks refuge or the ribs of the hut Itslk helps to build. Brubaker makes very imaginative use of a large piece of cloth that can be a sail, a tent or, most remarkably, the skin of the bear into which Elle transforms herself.

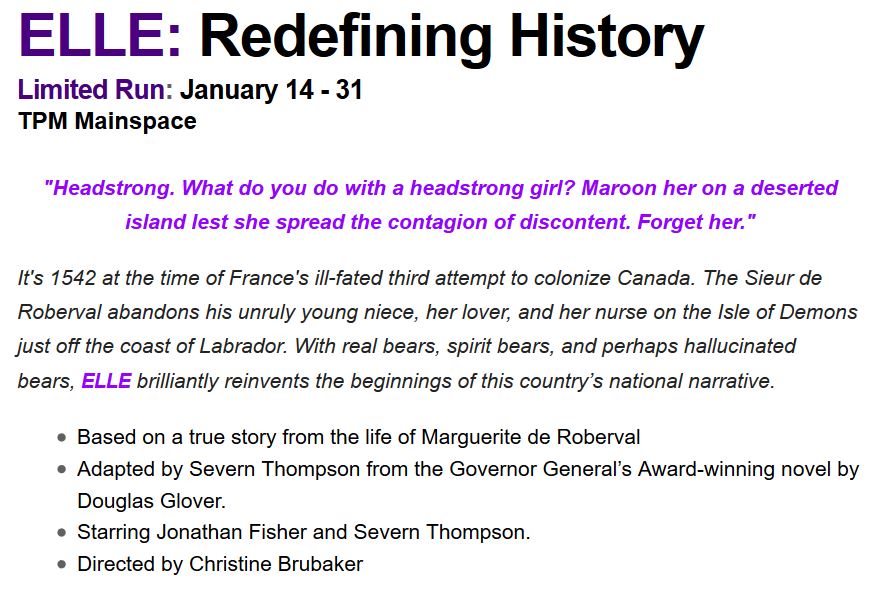

When Severn Thompson read the novel Elle four years ago she had no idea that this story would capture her imagination for years to come. The Governor General’s Award-winning novel written by Douglas Glover is based on the true story of Marguerite de Roberval. Marguerite, along with her lover and nurse, were marooned by her uncle the Sieur de Roberval on the Isle of Demons in the Gulf of the St. Lawrence. Thompson spent the last three years adapting and workshopping Elle before bringing it to Theatre Passe Muraille. “It struck me as so refreshing to find a female voice from a time I had heard very little about, in the very early days of the explorers in the mid 1500’s,” says Thompson. “I felt very close to her [the character]. The story crossed 500 years very easily for me. It brought the past to the present.”

Another review that’s positive despite not being able to keep The Revenant out of the lead. Jesus wept. 🙂

d

The biggest story in the film world right now includes hypothermia, parenthood, bear attacks and Leonardo DiCaprio’s potential first Oscar win in Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu’s The Revenant. Who knew its companion piece would be revealed at Toronto’s Theatre Passe Muraille, and that Hollywood’s favourite movie would share so many similarities with a story foundational to the creation of Canada.

In Elle, which had its world premiere this week at Passe Muraille directed by Christine Brubaker, writer and actor Severn Thompson adapts Douglas Glover’s 2003 novel of the same name into a mostly solo performance that weaves feminism, survival instincts, colonialism and magic realism together.

Here’s another review by a man who seems to think everything would be better as a movie and reviews the play as if it were a text and not a series of scenes and tableau-like images that, as the play wears on, remind you more of German Expressionist theatre than what he inappropriately calls “magic realism.” He makes no mention of the theatricality of the play. His descriptive vocabulary is minimal. “Tense” — what does that mean? And he obviously hasn’t read the novel. This is typical of a certain withered Toronto provincialism that equates the Academy Awards with the acme of our culture and thinks that by mentioning them you mark yourself as hip and in the know. 🙂

What can you expect from a newspaper that so badly read the mood of the country as to endorse Stephen Harper’s Conservative Party in the last election? And we all know how that went down.

dg

A white person left for dead in the North American wilderness in the days of conquest and colonization. A highly symbolic encounter with a bear – and local indigenous peoples. An epic journey of survival across a frozen landscape seeking revenge.

No, it’s not The Revenant, the Alejandro Iñárritu film leading this year’s Oscar nominations. It’s Elle, Douglas Glover’s 2003 Governor-General’s Award-winning novel – now transformed into an occasionally tense, but frequently funny play by the actress Severn Thompson.

Read the rest at The Globe and Mail.

Here’s a review excerpt.

In his program note, Andy McKim, Artistic Director of Theatre Passe Muraille, references author Douglas Glover (who wrote the book on which the play is based): “It was remarkable that she (Elle) survived by herself when the large expedition brought to colonize Canada by (her uncle) and Jacques Cartier couldn’t succeed. (Perhaps) her motives were somehow purer, that she was closer in her attitudes to what we might call the forces of life, and this allowed her also to be more open to native culture.” Or it could just simply be that Marguerite de Roberval (Elle) was one resourceful woman who knew how to suck it up, use what was available to her and embrace and respect her surroundings and survive.

Severn Thompson has adapted Douglas Glover’s book so that it lives on the stage. The language is eloquent and poetic. At one point Elle refers to “endless misty vistas.” I certainly don’t mind spending time in a theatre if I can listen to poetic lines like that, delivered with as much passion and life as Severn Thompson imbues in Elle.

Read the rest @The Slotkin Letter

So, okay, first night. Spectacular, magical. Standing ovation, curtain calls. A transformation of my novel for sure. But Severn Thompson was born to play Elle, the headstrong girl. Funny, passionate, poignant. A bravura performance, a woman holding us mesmerized for 90 minutes. Stunning visual effects, but theatre, cheap computer generated effects. The moment when she falls through the ice, amazing lighting effects, a column of light flickering as if water. Transforming into a bear using a lengthy sheet of gold material pulled against her body, her raised hands clawing against it (just amazing what theatre people can do with a sheet). Terribly poignant opening up of the play with the entrance of Jonathan Fisher as Itslk. Scene after scene, image after image. The scene where the baby Emmanuel dies. OMG. I don’t think many authors get a chance to see someone make another work of art of their own creation. And fewer still can be so pleased and moved and feel that such homage has been paid. I am going to bed now. Tomorrow I will resume my habitual sardonic mask. But tonight I was moved. Go see the play if you can.

d

Theatre Passe Muraille Artistic Director Andy McKim is going to do an onstage interview with dg at 6:45 Wednesday night just prior to the play performance at 7:30. This is a regular TPM feature called Eggrolls with Andy. It takes place on the cabaret stage on the balcony (near the bar). We’ll be talking about the novel, my female narrator, colonization, and various issues of indigeneity raised in the book.

Official premiere tomorrow night, January 19.

That’s at Theatre Passe Muraille, 16 Ryerson Ave, Toronto.

Box Office: 416 504 7529.

Rob Reid’s an old friend of some newspaper cronies of mine from days gone by. He’s been following and reviewing my work for ages. This piece has the added virtue of presenting some background material on the actress Severn Thompson who adapted my novel for the stage and is playing Elle.

d

I became a Douglas Glover fan in 1983 after reading Precious while working at the Brantford Expositor. Brantford is not far from where the writer was born in Simcoe, Ont. — I worked at the Simcoe Reformer before The Expositor. He was raised on a tobacco farm outside of nearby Waterford. Since then I have eagerly anticipated each new novel or, later, work of non-fiction. He has become my favourite postmodern, metafictional novelist — to think, our very own homegrown Italo Calvino.

Read the rest at Rob Reid’s Between the Lines: Elle Hitting the Boards.

Again, I am grateful to the director Christine Brubaker for posting these photos on Twitter. Wonderful to see the play in these stills.

#ElleTO

dg

.

Severn emailed me last night after dress rehearsal to say it went really well. Each iteration of the play builds on the rest. Last night was the first time with an audience, small, yes. A dress rehearsal.

Also yesterday Now ran a small piece on Severn and the play. The writer made a nice nod to my joke about Elle’s boyfriend being a tennis pro (in 1542).

Severn is quoted as saying:

“The book brought to life an early chapter of Canadian history. From the start I saw it as a staged piece, since the character expresses herself in a contemporary way that I could relate to,” Thompson says. “She might not be much more than a sidebar in history, but in this story she’s constantly saying, ‘Look at me, be aware that I exist.’

Yes, that was the point. Severn has consistently been one of my best readers.

Read the rest of the interview @Now.

#ElleTO

dg

.

Here’s a video just posted by Theatre Passe Muraille. Artistic Director Andy McKim discusses Severn Thompson’s stage adaptation of my novel Elle.

#ElleTO

dg

.

Another update on Severn Thompson’s play based on my novel Elle.

Christine Brubaker, the director, just posted this shot of the set on Twitter. The magic of theatre.

#ElleTO.

dg

Here’s an image the director Christine Brubaker posted on her Twitter feed earlier this afternoon. Just amazing to see my words made into a physical thing. And so beautiful.

Previews start Thursday, January 14. The official premiere is January 19, but, as I said, earlier that’s sold out.

I’ll be doing an onstage interview before the January 20th performance.

This is at Theatre Passe Muraille in Toronto.

dg

Severn Thompson’s adaptation of my novel Elle goes up at Toronto’s Theatre Passe Muraille this week, preview performances start Thursday. The official world premiere is January 19, already sold out. I’ll be there. And then I will participate in an onstage interview the second night, January 20.

Severn is a wonderful, magical actress. Two years ago she did a trial performance from the opening of the novel in a bare room above a bar in Toronto. Jonah and I were there. It was entrancing. Jonah kept punching me in the shoulder, whispering, “You wrote that!” Severn was doing a monologue in period costume, no other decor but for a straight backed chair, which she was having sex with (some of you will remember that opening scene).

I’ve been watching the script develop. After getting over the initial shock of seeing my 180 pages shrunk to about 45 pages, I’ve been fascinated, enthralled. The novel to stage adaptation process is not easy AT ALL. But Severn has found her own rhythm and line and the last draft gave me a thrill. Something really happening there. And with her charm and skill as an actress, not to mention the stage effects they have been working on, this should be an extravagant delight.

Watch the Theatre Passe Muraille Facebook page here. Twitter hashtag #ElleTO.

dg

Two Croatian guys who play the cello, Luka Šulić and Stjepan Hauser.

In August Ann Case and Angus Deaton published an amazing paper called “Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century” that has been roiling the waters of American journalism and politics ever since. The surprise discovery is that, while death rates in developed nations around the world are still dropping, in the US among white, non-hispanic (as they say) people between 45 and 54 the death rate is rising. Much of this rise is attributable to self-inflicted harm such as substance abuse and suicide. It’s also the case that white people with less money and education are the ones dying off. Well-off, well-educated white people are still fine.

Debates about what this means have been all over the map. But I just read this piece by Josh Marshall at Talking Points Memo, which is very smart, reasonable, and suggestive.

Basically, Marshall writes, the die off indicates a radical loss of hope and future due to the fast-shifting demographics and power structure in the United States. The American population is changing; old race and class structures are beginning to crumble (not a moment too soon). The people with the least capacity for living with change are the ones at the bottom of the heretofore privileged class.

This thought structure, it seems to me, has been preserved through to the 21st century in one form or other. But the contradictions of reality are finally beginning to impinge. The rage of the Tea Party and the Trumpite GOP points straight at the symbols of threatened privilege from political correctness to Planned Parenthood to voter registration to American Muslims to the Confederate flag.

Now what’s really interesting to me is the fact that when the left thunders against white privilege it paints all whites as privileged. And they are. But the generalization misses the nuance: a majority of underclass whites have NO PRIVILEGE ASIDE FROM RACE. The black slaves called them poor white trash[3] and looked down upon them (which only enraged them more). Structural racism has been the ONLY PRIVILEGE these people have enjoyed. And now it’s being taken away from them. Now they must face the fact that they have nothing of their own to fall back on. No resources, no education, no special rights, no reserved place in society, no identity.

Let me say this again. The trouble with accusations of white privilege (and what makes lots of underclass whites angry) is that a large number of white people are not privileged at all, can’t get jobs, have no influence or pull, except that they are white and can FEEL better than people of colour. This is not a real position of privilege; it’s more of a phenomenological sense of superiority. It’s ugly, a fantasy, and self-deceiving, but it makes them feel better about themselves. More or less consciously, this is a perceived superiority, an identity, they don’t want to give up. And it’s all they have.

To fill out the nuance I need to add that white privilege is a fact. Nothing I’ve said explains that away at all. But there are several more or less distinct classes of white people and privilege. There are certainly some well-educated, cosmopolitan white people who are comfortable with change and a multi-racial society. And then there is an oligarchic class of white privilege that really does want to maintain power, influence, and status. This is the equivalent of the planter class in the South prior to the Civil War, a class that used paranoia and racial separation to manipulate and control both black and white underclasses. Then, as now, the white underclass, the violent, impoverished good old boys were/are the truly dangerous crowd. And they are mad. They will not go down quietly.

But wouldn’t it be nice if they got mad at the people who are actually responsible for their manipulation and subjugation (hint: not black people, not Hispanics, not natives, not Muslims, not Jews, not women…). Instead of letting voices of oligarchic privilege orchestrate their anger (as the planter class did in the Old South; think: how did they get all those poor, non-slave-holding, good old boys to fight in the Army of Virginia?), imagine them turning their anger on the appropriate parties and voting them away.

This is not say that poor, ill-educated white people are just plain awful. But history, poverty, and class have dropped an evil cage over their heads that is increasingly difficult to escape. They have fewer avenues for individual betterment and fewer avenues for political expression, at least avenues in the old sense. Change is increasingly not an avenue they embrace; they rant against it and cheer on the demagogues. Under stress, hopeless, their mudsill of identity crumbling, they opt increasingly, on the one hand, for the well worn paths of hatred and resentment, and on the other hand, for the dubious escape of substance abuse and even suicide.

[A somewhat analogous drama has been working itself out in Canada, where the Conservative government, now defeated, ran on neo-liberal, tea partyish, divisive policies, playing up Muslim threats and crime issues (all code for protecting what the then prime minister called “old stock Canadians” which is code, yes, for white Anglo people). When Justin Trudeau was elected, he quickly put together a cabinet that is 50% women and included a man in a wheel chair, Sikhs, native Canadians, and French-Canadians. When asked about the diverse profile of his cabinet, he had two reactions. 1) He wanted the cabinet to look like Canada as whole. 2) It’s 2015. This is a man comfortable with change.]

Read Josh Marshall’s text “You Can’t Understand American Politics Without Reading This Study” here @Talking Points Memo.

A day later Marshall added new charts and figures based on a critique of the original study. The new graphs don’t change the thrust of his essay, but they add fascinating specificity to the original stats. For example, it turns out white women have a death rate rising faster than white men.

dg

- “What Cash develops throughout his book is what he identifies as the enormously hedonistic quality of the Southern people. He sees them as self-satisfied, complacent. They will not be diverted from their smugness, their unwillingness to look critically at what they are, with the result that throughout their history anyone who has attempted to point out to them the extent to which they are being used and manipulated for the benefit of those in power has been unable to get anywhere. Conversely, those who have flattered their self-esteem and confirmed them in their prejudices have been able to manipulate them to vote and act contrary to their own economic and political interests.” W.J. Cash After Fifty Years By Louis D. Rubin in http://www.vqronline.org/essay/wj-cash-after-fifty-years↵

- There, at the core of Southern capitalism, Johnson detailed how the masters performed a kind of ritual, conjuring their own whiteness and masculinity as they jockeyed for status at the slave pens. In turn, because so much of the master’s sense of his own self rested on the situation at the auction block, slaves had an opportunity to manipulate their buyers and sellers, and thereby their own fate. While the masters built their identities by performing for one another, the slaves preserved their lives by performing for their buyers—all morbid “advertisements for myself” in the charnel house of Southern consumerism.” Gabriel Winant in “Slave Capitalism” in N+1 Issue 17: The Evil Issue Fall 2013↵

- “The term white trash first came into common use in the 1830s as a pejorative used by house slaves against poor whites. In 1833 Fanny Kemble, an English actress visiting Georgia, noted in her journal: “The slaves themselves entertain the very highest contempt for white servants, whom they designate as ‘poor white trash'” ” This is from a fascinating discussion of the origins of the phrase at http://english.stackexchange.com/questions/41778/what-is-the-early-recorded-use-of-white-trash-and-has-its-meaning-changed-over↵

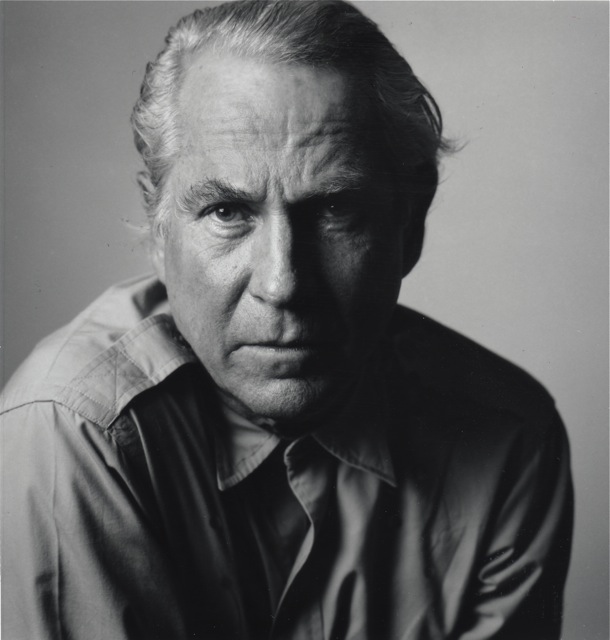

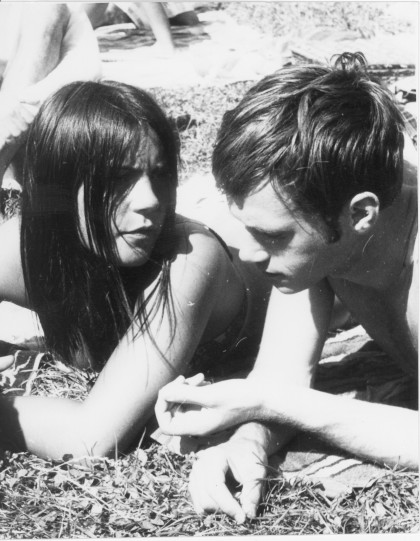

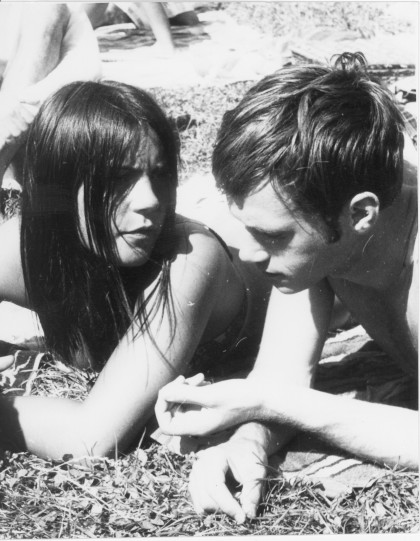

This photo of DG (as Existential hero) and the mysterious SE at the pool in Freiburg im Breisgau dates from about the time he first read Camus, 1968, and is included with the essay for context.

My essay on Camus is now up online in its entirety at the CNQ: Canadian Notes & Queries.

Here’s what I wrote when the print edition came out a few weeks ago.

Last year, Kim Jernigan, the estimable, indefatigable, generous, and wise former editor of The New Quarterly, emailed me to say she was putting together a special edition of the journal CNQ: Canadian Notes & Queries, and would I write an essay for it. The focus, the demand, was for an essay about rereading: pick a book I had read long ago and recently reread, and write an essay about the difference between the readings (and, perhaps, the difference between me then and me now). I leaped to the task, having just taken another look at Camus’s L’Étranger after years of remembering it a certain way, fixed in my mind since my first reading as a freshman at university. I discovered a new and truly remarkable book. I also discovered that, yes, I am only beginning to learn to read.

CNQ is a print magazine with a website attached. Issue number 93 is just out. Here are the opening paragraphs of my essay.

§

I was eighteen when I read L’Étranger for the first time. I read it in French in a freshman class at York University in Toronto, probably read it in English simultaneously. I think I even wrote an essay about it in French, and that essay might still exist somewhere in a box. Or possibly I dream this, trying to impress myself. I still do remember lines of poems I memorized that year: Mignonne, allons voir si la rose / Qui ce matin avoit desclose / Sa robe de pourpre au Soleil.…

I remember the instructor, a pale, heavy-lidded young man who rarely rose from the chair behind his desk, droning on with his face in a book. He wore a shiny grey suit and a white shirt open at the neck, which I took to be Continental attire. His eyes were invariably puffy and irritated – the word dissipated comes to mind now. I often sat next to a girl named Karen Yolton who was also sleepy, wore black nail polish but nervously tore her cuticles, and whispered scandalous tales of her escapades in a city that was new and alien to me.

I was a little lost and amorphously rebellious and wanted desperately to be an outlaw. I got an F on my first English paper. And perhaps this bled into my reading of Camus, especially Meursault’s carefree sensuality with his lover Marie and his inarticulate defiance of conventional normative language. I remember my teenage outrage at being told to feel what I didn’t feel. That was the thing you noticed in the novel as a young person — the appeal to false authority, the sense of people asking things of you that you didn’t feel and you didn’t feel like giving. Hell, I wanted to sleep with girls and defy authority; Meursault and I were one in my heart, aside from, you know, the small matter of shooting the Arab to death on the beach.

Somehow I always slid over the actual murder any time I summarized the novel to myself, seeing Meursault as a victim of social and linguistic tyranny not a confessed killer. Camus himself famously, and perhaps mischievously, confused his readers by saying, “In our society any man who does not weep at his mother’s funeral runs the risk of being sentenced to death.” This is neither an accurate description of the French criminal justice system nor the novel itself. Meursault shoots the Arab once, then pauses before pumping another four bullets into his body. Meursault’s interrogation before the examining magistrate turns on this fact, for which he has no explanation. But it shreds any chance of his pleading self-defense.

I was eighteen, as I say, and enamoured with the outlaw girl I met in French class, with her ragged cuticles, cigarette rasp, and freckles, and I had no clear idea what Existentialism was except insofar as I had seen a picture of Camus, looking dour and swarthy with a cigarette in his mouth, and somehow had decided this was the very image of the Existentialist hero, a phrase I now realize is an oxymoron, and I would imagine Karen, Camus/Meursault, and myself becoming really good friends, comrades against the (adult) world.

I adopted Existentialism as an attitude rather than an idea. Though deep down I quickly divined the speciousness of its crucial ethical argument, the basic and unworkable paradox of having to create value by making decisions without recourse to values. In time, I came to realize that Existentialism hadn’t amounted to much, had quickly been abandoned even by Sartre who invented it (he became a Communist, then a Maoist). It was only a moment in a long argument in the West between the language of the gods and the language of a world without a supernatural life support apparatus, a world without gods, a world of mere existence. This argument culminated first with Descartes’ Radical Doubt and later, in the early 20th century, in Edmund Husserl’s Cartesian Meditations, after which philosophy veered sharply away from metaphysics into various branch lines: phenomenology, language philosophy, critical theory, structuralism, etc. Existentialism, an extreme 20th century application of systematic doubt, is a version of positivism with a concomitant impoverishment in the ethical and emotional sphere; the human aspect of language wilts.

But at first reading, the critical attitude, the defiant rejection of traditional values, melded seamlessly with my hormones and the biases of the hour: late 1960s counter-culture, Vietnam war protests, the Free Speech Movement, and nationalist revivals in both English Canada and in Quebec. Like many people, I read L’Étranger through the zeitgeist. I had lost my sense of humour, and in my yearning for simple positions, it never occurred to me that a novel might be beautiful, funny, tragic, and mysterious all at once.

Read the whole essay at Douglas Glover: Making Friends with a Stranger: Albert Camus’s L’Étranger @ CNQ: Canadian Notes & Querie.

.

.

Some more pictures from the NC bunker. The light is grand, and, of course, uncapturable. The top couple of images are looking west at sunset. I’m not trying to show you what it really looks like. The effects are meant to exaggerate the light and dark, the patterns thereof. The middle two images are attempts to get the light streaming into the woods from behind. And now that the leaves are mostly gone I can see things I couldn’t before. Camel’s Hump looms in the distance, dark and ominous. The very bottom image is a snow squall coming over the Worcester Mountains in the west, a sign of the future.

Naturally, it’s terrifying and time-consuming to live in such a dramatic environment and I get no work done. What work? Lucy asks.

dg

Last year, Kim Jernigan, the estimable, indefatigable, generous, and wise former editor of The New Quarterly, emailed me to say she was putting together a special edition of the journal CNQ: Canadian Notes & Queries, and would I write an essay for it. The focus, the demand, was for an essay about rereading: pick a book I had read long ago and recently reread, and write an essay about the difference between the readings (and, perhaps, the difference between me then and me now). I leaped to the task, having just taken another look at Camus’s L’Étranger after years of remembering it a certain way, fixed in my mind since my first reading as a freshman at university. I discovered a new and truly remarkable book. I also discovered that, yes, I am only beginning to learn to read.

CNQ is a print magazine. Issue number 93 is just out, but you’ll have to order a copy to read it. But here are the opening paragraphs.

This photo of DG (as Existential hero) and the mysterious SE at the pool in Freiburg im Breisgau dates from about the time he first read Camus, 1968, and is included with the essay for context.

§

I was eighteen when I read L’Étranger for the first time. I read it in French in a freshman class at York University in Toronto, probably read it in English simultaneously. I think I even wrote an essay about it in French, and that essay might still exist somewhere in a box. Or possibly I dream this, trying to impress myself. I still do remember lines of poems I memorized that year: Mignonne, allons voir si la rose / Qui ce matin avoit desclose / Sa robe de pourpre au Soleil.…

I remember the instructor, a pale, heavy-lidded young man who rarely rose from the chair behind his desk, droning on with his face in a book. He wore a shiny grey suit and a white shirt open at the neck, which I took to be Continental attire. His eyes were invariably puffy and irritated – the word dissipated comes to mind now. I often sat next to a girl named Karen Yolton who was also sleepy, wore black nail polish but nervously tore her cuticles, and whispered scandalous tales of her escapades in a city that was new and alien to me.

I was a little lost and amorphously rebellious and wanted desperately to be an outlaw. I got an F on my first English paper. And perhaps this bled into my reading of Camus, especially Meursault’s carefree sensuality with his lover Marie and his inarticulate defiance of conventional normative language. I remember my teenage outrage at being told to feel what I didn’t feel. That was the thing you noticed in the novel as a young person — the appeal to false authority, the sense of people asking things of you that you didn’t feel and you didn’t feel like giving. Hell, I wanted to sleep with girls and defy authority; Meursault and I were one in my heart, aside from, you know, the small matter of shooting the Arab to death on the beach.

Somehow I always slid over the actual murder any time I summarized the novel to myself, seeing Meursault as a victim of social and linguistic tyranny not a confessed killer. Camus himself famously, and perhaps mischievously, confused his readers by saying, “In our society any man who does not weep at his mother’s funeral runs the risk of being sentenced to death.” This is neither an accurate description of the French criminal justice system nor the novel itself. Meursault shoots the Arab once, then pauses before pumping another four bullets into his body. Meursault’s interrogation before the examining magistrate turns on this fact, for which he has no explanation. But it shreds any chance of his pleading self-defense.

I was eighteen, as I say, and enamoured with the outlaw girl I met in French class, with her ragged cuticles, cigarette rasp, and freckles, and I had no clear idea what Existentialism was except insofar as I had seen a picture of Camus, looking dour and swarthy with a cigarette in his mouth, and somehow had decided this was the very image of the Existentialist hero, a phrase I now realize is an oxymoron, and I would imagine Karen, Camus/Meursault, and myself becoming really good friends, comrades against the (adult) world.

I adopted Existentialism as an attitude rather than an idea. Though deep down I quickly divined the speciousness of its crucial ethical argument, the basic and unworkable paradox of having to create value by making decisions without recourse to values. In time, I came to realize that Existentialism hadn’t amounted to much, had quickly been abandoned even by Sartre who invented it (he became a Communist, then a Maoist). It was only a moment in a long argument in the West between the language of the gods and the language of a world without a supernatural life support apparatus, a world without gods, a world of mere existence. This argument culminated first with Descartes’ Radical Doubt and later, in the early 20th century, in Edmund Husserl’s Cartesian Meditations, after which philosophy veered sharply away from metaphysics into various branch lines: phenomenology, language philosophy, critical theory, structuralism, etc. Existentialism, an extreme 20th century application of systematic doubt, is a version of positivism with a concomitant impoverishment in the ethical and emotional sphere; the human aspect of language wilts.

But at first reading, the critical attitude, the defiant rejection of traditional values, melded seamlessly with my hormones and the biases of the hour: late 1960s counter-culture, Vietnam war protests, the Free Speech Movement, and nationalist revivals in both English Canada and in Quebec. Like many people, I read L’Étranger through the zeitgeist. I had lost my sense of humour, and in my yearning for simple positions, it never occurred to me that a novel might be beautiful, funny, tragic, and mysterious all at once.

.

Read the entire essay at CNQ 93, which has just been published but not yet linked at the web site.

The issue also includes work from Numéro Cinq contributors Caroline Adderson, Susan Olding, and Jeff Bursey, as well as Chris Arthur, Marc Bell, Kathy Friedman, Jason Guriel, the legendary bookseller David Mason, Peter Sanger, Robin Sarah (who just won a Governor-General’s Award), Carrie Snyder, JC Sutcliffe, Jess Taylor, and Anne Marie Todkill.

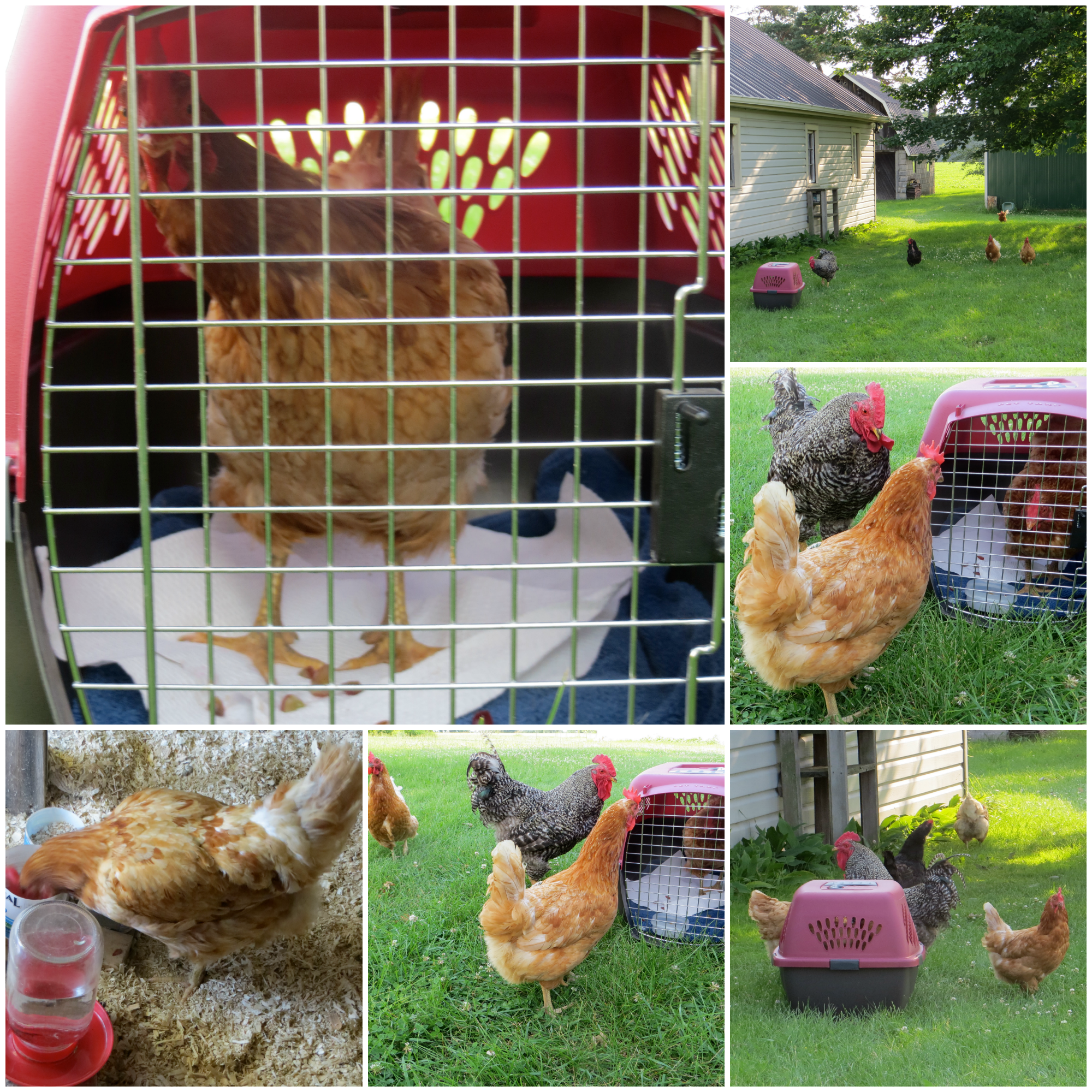

There is a tide and time in the lives of chickens, as there is in the lives of men and women. Many of you have watched the rise and fall of the hen population on the farm with amusement and sympathy. But things have gone south. In late spring, a Cooper’s Hawk took the third to last hen. Then the second to last fell sick and died (they were all getting old for chickens). And finally Jean broke her hip a few weeks ago (um, she’s 94), putting an end to plans for repopulation. Chickens are social animals and aren’t happy on their own. While Jean was AWOL in the hospital, I got in touch with Amber Homeniuk, poet (see her poems in the current issue) and Jean’s favourite chicken expert, who offered to rescue ours.

Here we have images and video of the last moments. Amber came prepared with a chicken carrier, also sliced grapes and chicken feed. And you can tell from the video what a gentle and reassuring animal wrangler she is.

Below the video is a collection of images Amber put together of the first moments at the other end of the exchange.

More about chickens than you ever wanted to know, right? But I’ll miss them. Surprising, sociable creatures. Nice to have around the place.

dg

Due to ongoing death threats, drive-by shootings, kidnappings, lawsuits, federal investigations, vehicle repossessions, and debt collections, the usual fare of literary magazine publication, Numéro Cinq has relocated its headquarters to a hardened bunker somewhere in Vermont. For your edification, a selection of the usual boring Vermont vistas taken from the backdoor, looking west toward Camel’s Hump, the Worcester Mountains, and Mount Mansfield. Also some woodsy shots with dogs. Neighbours report a “small” 300-lb black bear living across the road. DG needs a new camera for this.

The best part is that nobody can find him.

dg

Tim Groenland has written a compendious and measured account of Gordon Lish’s editing practice (fascinating images of pages edited — Nabokov, for example) and influence, minus the Raymond Carver hysteria. The essay builds on some of the work we’ve published at NC, including Jason Lucarelli’s ground-breaking texts “The Consecution of Gordon Lish: An Essay on Form and Influence” and “Using Everything: Pattern Making in Gertrude Stein’s ‘Melanctha,’ Robert Walser’s ‘Nothing at All,’ and Sam Lipsyte’s ‘The Wrong Arm’” plus my own audio interview “Causing Damage — Captain Fiction Redivivus: DG Interview With Gordon Lish.” All are quoted in Groenland’s piece, putting NC at the front of the wave of new interest in Lishian studies.

dg

Here’s a teaser from the Groenland essay:

These studies make it clear that Lish was, in certain ways, “the minimalist in the machine” in Carver’s work (Churchwell n.p.) and it is clear that he applied similar techniques to the work of other young writers of the period: Lish was instrumental in the early careers of Barry Hannah and Mary Robison, for example, making him an essential figure in the development of what was variously known as “minimalism”, “Dirty Realism”, and “the new realism” (or, to use Mark McGurl’s recent formulation, “lower-middle-class modernism”) in the early 1980s (32). Michael Hemmingson has shown that Lish edited Barry Hannah’s fiction extensively throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s: he reports, for example, that the manuscript drafts for Hannah’s novel Ray (1980) are “a confusing, sloppy mess” and that Lish’s editing work here involved carefully rearranging sections into narrative coherence, much as Max Perkins did for Thomas Wolfe’s major novels (Hemmingson 490–491; Berg 119–130, 223–228). Lish performed line editing on photocopies of Hannah’s stories taken from the journals in which they had been printed, just as he did with Carver’s work: in several cases, the journal in question was Esquire, meaning that the editor often saw Hannah’s work through several iterations and could refine his vision of the stories in different stages. Hannah’s attitude to these changes was markedly different from Carver’s, and in a 2004 interview with the Paris Review he was unambiguous in his praise:

Gordon Lish was a genius editor. A deep friend and mentor. He taught me how to write short stories. He would cross out everything so there’d be like three lines left, and he would be right . . . This is your good stuff. This is the right rhythm. So I learned to write better short stories under him. (Hannah, “Art of Fiction 184”)

Read the entire essay @ Irish Journal of American Studies.

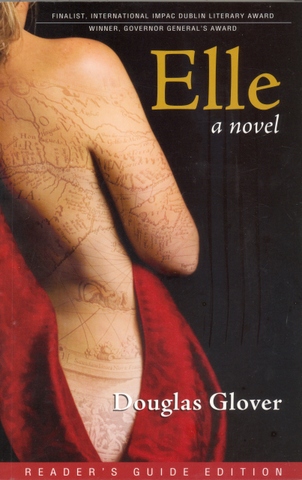

I checked the Theatre Passe Muraille website this morning and found the 2015-2016 season announcement. And at the top of the announcement page there is this lovely poster announcing Severn Thompson’s adaptation of my novel Elle, which, as you all know, won the Governor-General’s Award and was a finalist for the Dublin IMPAC Award.

This isn’t a surprise, of course. I saw a tiny workshop preview of an opening to the play at a festival in Toronto in August, 2013, and Severn Thompson has been in touch all along. But it is lovely to see the announcement up and the dates set.

Book the date!

dg

Here’s another dyspeptic comedy, a cracked romance (there is a dark, dark love angle), from the hand of Douglas Glover, just published in the July-August issue of The Brooklyn Rail. What to expect? Well, the protagonist’s name is Drebel, a combination of dreadful and rebel. Click on the link below the teaser or the cover image above to read the entire piece.

Drebel started when he was fourteen organizing a grocery shopping service for the elderly in his neighborhood. He charged a flat rate per bag, accepted gratuities, and handled the cash exchange between the grocery store and the old people. Once he gained a customer’s trust, he would skim a percentage off the change, especially when the old man or woman couldn’t see that well. He would smile winningly while counting out the money; the old folks loved having a young person to socialize with. Seeing themselves reflected in his eyes, they thought they were smart, plucky oldtimers. Later, he was able to arrange a small quid pro quo from the supermarket manager’s petty cash to steer his customers away from competitors. He never bought bulk or generic. When an elderly party insisted on cheaper brands, Drebel would shrug and say the store was out. He watched for customers whose memory was failing and preyed on them, lifting a hundred dollar bill from the open purse or pocketing an expensive watch from the sideboard. Once he swiped a handful of silver cutlery from a drawer, sweeping it into his courier bag and clanking out the door. But he had trouble fencing the forks and spoons, and he was really only interested in the cash. He couldn’t help becoming fond of the old woman who said she would put him in her will, though he knew she wouldn’t. He didn’t take any offer of warmth or affection personally. He knew the old people were wrapped tight in their narrow lives, narrower and narrower as they grew older. They could be just as devious and mean as the next person. Drebel noticed how the codgers took a perverse pride in trying to shortchange him, arguing over the receipts, shaving the tip. “Here’s another quarter, son. Oh, drat. I thought I had another quarter. Next time?” He didn’t care. All he wanted was his cut, the skim.

Read the rest at The Brooklyn Rail.