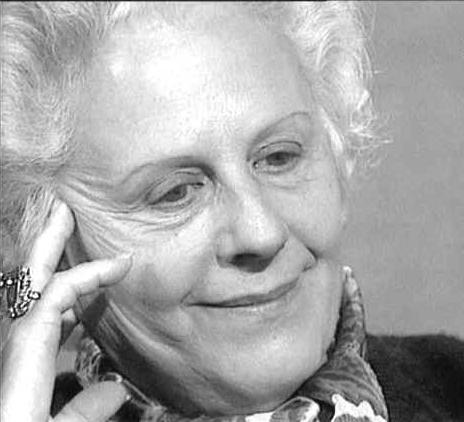

Richard Jackson, Betanja, Slovenia, June 2008. Photo by Douglas Glover

Richard Jackson, Betanja, Slovenia, June 2008. Photo by Douglas Glover

Richard Jackson is an old friend, an eminent colleague at Vermont College of Fine Arts where he teaches poetry and translation, and an indefatigable traveler and spirit guide (dg spent nearly 2 weeks in Slovenia with Rick, during the 2008 VCFA summer residency—see photo above—dg is still recovering). Richard Jackson is a prolific poet, a great humanitarian, a man of immense culture and erudition, and a gifted translator. He raises the bar. When you’re around Rick, you want to read more, see more art, learn more languages, and travel to distant fabled places.

dg

.

I

Why translate? Kenneth Rexroth, one of the most influential translators, writes in his essay, “The Poet as Translator,”– “The writer who can project himself into exultation of another learns more than the craft of words. He learns the stuff of poetry.” Translation is at the heart of poetry– a poet like Rilke writes in his “Ninth Elegy” that when the poet

returns from the mountain slopes into the valley,

he brings, not a handful of earth, unsayable to others, but instead

some word he has gained, some pure word, the yellow and blue

gentian. Perhaps we are here in order to say: house,

bridge, fountain, gate, pitcher, fruit-tree, window–

at most: column, tower….But to say them, you must understand,

oh to say them more intensely than the Things themselves

ever dreamed of existing.

Rilke’s notion that words only metaphorically stand for ideas, sensations and feelings suggests that they are themselves a form of translation. Of course, this could lead us quickly into a maze of problems and suggest that even a poem in our own language must be “translated.” What is at issue in translating poetry is the very nature of poetry, and the very nature of language. The main problems and debates that arise concerning the translation of poetic works occur when one realizes to what extent the essence of a poem lies, as Rilke and Rexroth suggest, beyond the words per se.

First, I want to point out that literary translation differs in many important respects from the kind of translation that is usual in a language class. Literary translation, for one, involves a good deal of interpretation about intent and effect. For another, it is often not so interested in a literal “transliteration” as much as finding a corollary mood, tone, voice, sound, response–any number of issues can be raised here. John Dryden, the great neoclassical poet, wrote in his “Preface to Pindaric Odes,” that translation should be “not so loose as paraphrase, nor so close as metaphrase.” A poet such as John Nims feels that the most important thing to translate is sound; for him, the pure music of the poem is most crucial. James Wright in translating Hesse’s poems aims to duplicate their emotional effect more than any technique such as sound per se. Robert Bly’s translations are extremely loose yet often capture the essence of Neruda’s and Rilke’s spirits.

“Poetry is what is lost in translation,” wrote Robert Frost, a notion we have probably all heard. “Poetry is what is gained in translation” wrote Joseph Brodsky, the Nobel prize winning Russian poet who also spoke several languages. Or as Octavio Paz, the Mexican Nobel prize winning poet says, “poetry is what gets transformed.” Ezra Pound, in “How To read,” describes three aspects of the language of poetry: melopoeia, its music; phanopoeia, the imagistic quality; and logopoeia, “the dance of the intellect among words.” It is this last aspect that Pound says is the essence of poetry, Rilke’s unsayable. What Brodsky, Pound and Paz were driving at was that there are intangible things, that the realm of the wordless and visionary, as Dante himself says in Paradiso XXXIII , is both untranslatable while also being the essence of poetry. Brodsky may be echoing Boccaccio’s notion in Genealogia Deorum Gentilium, X,7, where Boccaccio says that in listening to the Greek Iliad in Latin translation “some passages I came to understand very well by frequent interpretation.” And the renowned Swedish poet, Tomas Transtromer, writes that a poem is a manifestation of an invisible poem that is written beyond languages themselves. “Languages are many but poetry is one,” says the Russian poet Andrei Voznesensky.

Where does this leave us? Yang Wan-Li, a Chinese poet, once wrote about poetry and translation: “If you say it is a matter of words, I will say a good poet gets rid of words. If you say it is a matter of meaning, I will say a good poet gets rid of meaning. ‘But,’ you ask ‘without words and without meaning, where is the poetry?’ To this I reply: ‘get rid of words and get rid of meaning, and still there is poetry.’” It is that intangible that is left that is the object, I suggest, of good translation. That is why the contemporary poet and translator, Jane Hirshfield, says: “A literal word-for-word trot is not a translation. The attempt to recreate qualities of sound is not translation. The simple conveyance of meaning is not translation.” She is perhaps echoing the great Latin poet Horace who writes in his “Art of Poetry” (Ser. II,iii)that a good translation of Homer can exist only:

if you don’t try to render word by word like a

slavish translator, and if in your imitation you do not

leap into the narrow well, out of which either shame

or the laws of your task will keep you from stirring a step.

The step image, by the way, is a pun of the use of “poetic feet,” a way to measure rhythm. Horace’s and Wan-Li’s notions have been echoed through the ages. In our own day Octavio Paz says: “After all, poetry is not merely the text. The text produces the poem: a sense of sensations and meanings….With different means, but playing a similar role, you can produce similar results. I say similar, but not identical: translation is an art of analogy, the art of finding correspondences. An art of shadows and echoes….of producing, with a different text, a poem similar to the original.” This leads us to an essential irony: Stephen Mitchell, the well known translator of Rilke, says that “with great poetry, the freest translation is sometimes the most faithful.” And the great English poet, translator and critic, Samuel Johnson, who was one of the most conservative critics of the neoclassical period, wrote: “We try its effect as an English poem; that is the way to judge the merit of translation.”

.

II

Let’s look at a small portion of Dante’s text, the opening stanza of the Inferno, as a way to see look at the problems involved in such judgements . The four versions I’ll briefly look at are John Ciardi’s standard translation which strives to duplicate the colloquial effect of the language as well as some rhyme, Mark Musa’s relatively accurate literal version which uses a three line unrhymed stanza which renders an accurate sense of the poem’s meaning and scope, even the play of its metaphors, yet does not provide any of the poem’s tonal qualities, Robert Pinsky’s terza rima version strives to capture more of the varied aspects of Dante’s language, and Michael Palma’s new colloquial terza rima version that adds a great deal of interpretive material. One could say, as with Ovid, that in all these translations one is not reading Dante but only a translator, but of course that is also true for an Italian of today who must not only cope with archaic words and word forms, but also the different force and even connotative meaning of images and metaphors. We can gain a basic insight into these versions by looking at the opening stanza:

First here is the Italian and a literal transcription:

The road, first of all, is both literal, and as we soon learn, spiritual, the Biblical, “straight and narrow” road to salvation. Note that the loss is in the passive voice—Dante the pilgrim narrator is incapable of admitting at this point in the poem what Dante the poet knows: he is ethically confused and about to lose his soul. Ritrovai has special problems: to be lost and found is a basis of the Christian faith Dante is writing out of, yet the primary meaning of the word in the reflexive (mi ritrovai) is to meet another, also to come to consciousness, —which explains why some translators will use “came to myself” (though some use the reductive “awake”) emphasizing the spiritual split inside the narrator. Similarly, “straight” and “right” might be spiritual equivalents, but they suggest two different moods, the second being more directly a matter of ethics. Similarly dark and shadowy pose two distinct choices, both with Biblical connotations, shadowy suggesting more of the Hebrew Bible. Note also that Dante uses two words for the road—perhaps suggesting the road mortal people usually take as opposed to the correct path of righteousness.

While Ciardi’s version retains much of the colloquial energy of the original, he makes the narrator admit his fault (“I went astray”), which goes against the dramatic unfolding of the poem, for Dante’s narrator does not understand his own guilt and is in fact filled with pride and the inability to perceive sin accurately. Ciardi gives us:

Midway in our life’s journey, I went astray

From the straight road and woke to find myself

Alone in a dark wood. How shall I say….

Much of the drama of the poem rests in his struggle to separate his emotional sympathy for sin from his rational knowledge of evil. This sort of split is not something common to Ciardi’s own poems, either, which are straightforward and confessional– as is his translation. In many ways we are reading Ciardi using Dante as a way to describe his own self. To really understand what Ciardi is doing and the relation between his poem and Dante’s, one should read some of Ciardi’s poems along with his translation: what we find is the same forceful, direct, driving voice that the translation offers. Understanding this, we can extrapolate in order to imagine Dante’s quieter and more lyrical voice behind Ciardi’s. We can under stand, for example, that “Went astray” seems to lower the stakes while it lowers the linguistic level in a way that works better in Ciardi’s own poems than in this translation. We begin, in other words, to understand Ciardi’s approach as a sort of “common man” approach to the poem.

Mark Musa’s version suggests that Dante’s drift was part of a sleep, for now he awakens, a very literal and reductive interpretation of mi ritrovai not as a coming to consciousness, but a mere waking up– Musa’s pilgrim also states that the wandering was his own fault, as Ciardi’s does. By using “path” he also emphasizes the physical dramatic setting of the woods:

Midway along the journey of our life

I woke to find myself in some dark woods,

for I had wandered off from the straight path.

Musa’s use of “some” suggests a kind of casualness, at least as much as Ciardi’s, though he probably means it to heighten the narrator’s sense of being lost. This casualness– perhaps a product of our age’s fascination with freer verse forms and the looser Wordsworthian and Frostian blank verse– dominates Musa’s account, which is hardly a poetic step above the plain prose account of Mark Singleton. Musa doesn’t really provide a range of rhetoric, a range that is essential to Dante’s poem, and which a translator like Pinsky strives for. If we use Musa’s account, then I think we have to look at the influences that have led him to his form– to much of the poetic strategies of mainstream contemporary American poetry (he’s not a poet himself). Still, understanding that allows us to start to be able to perhaps take a step back towards understanding the difference in poetics between our world and Dante’s world, and gauge at l4ast the force of his metaphors which Musa remains absolutely loyal to.

For my money, the best current versions are those by Robert Pinsky and Michael Palma. Pinsky’s tries to be formal where Dante is formal, more rough and colloquial where Dante is Colloquial, imitates formal elements in the rhetoric such as anaphora and parallelisms, and generally keeps the tone. He also suggests something of the pace of the original, ironically by condensing it somewhat. Here is Pinsky’s opening:

Midway on our life’s journey, I found myself

In dark woods, the right road lost. To tell

About those woods is hard—so tangled and rough…

Pinsky leaves the responsibility for the way being lost ambiguous which I think is a good interpretation of Dante’s sense of things at this point. Pinsky places the reference to the tangled wood, which occurs in Dante a few lines later, at this point, allowing, as dante intended, the tangle refer to the pilgrim’s words nand ideas as well as the physical path. If we continue through his version we find Pinsky echoing the harsh onomatopoeic effects Dante uses to describe the lawyers in later in the poem, and imitating the song-like anaphora Francesca uses to seduce the Pilgrim in her “imbedded” lyric within canto V. Pinsky raises and lowers the linguistic register just as Dante does and the reader leaves the poem with a pretty fair sense of what the poem is trying to do.

Michael Palma’s version, which seems to lean on Pinsky’s, uses slant rhymes as well as full rhymes, and also the interlockings of terza rima in an interesting new version, though one must be also aware of interpretive additions or juxtapositionings which place in a half notch below Pinsky’s version:

Midway through the journey of our life, I found

Myself in a dark wood, for I had strayed

From the straight pathway to the tangled ground.

Of course, some of what he adds is to fill out the rhymes, but in doing so he inadvertently emphasizes the physical journey over the spiritual with “tangled ground” by including it in this first sentence rather than a tad later where it actually occurs. And he also allows the narrator to be more conscious of what his own culpability is than Dante’s narrator, as Ciardi and Musa do– all three of them perhaps falling prey to the sort a sort of guilt complex that seems to have entered much contemporary poetry and consciousness. Palma’s very colloquial version also seems to sometimes create a suburban inferno; his use of “pathway” here suggests a kind of jogging path, an effect one also sees in Longfellow’s 19th century version.

One could say that in all these translations one is not reading Dante but only a translator, but of course that is also true for an Italian of today who must not only cope with archaic words and word forms, but also the different force and even connotative meaning of images and metaphors. One answer is simply to not read any version because it is not the author per se, but that would lead to a pretty narrow view of our literary heritage. (What would happen if the same principle were applied to the UN where speeches are given and translated but cannot translate nuances of meaning, tone, voice, rhythm, etc.?)

.

III

In recent years translators have taken to collaborative efforts, often translating language they do not know or know very little. Such collaborations, usually between a good linguist or native speaker and a good poet have resulted in some stunning translations. Usually the poet is provided with a literal translation, then works with the translator over phrases and words with colloquial, historical or metaphoric resonance, and then the poet comes up with a poem that is a version, imitation (fairly close) or adaptation (loose). This, too, is an old practice: Johnson, for instance, describes it in his description of Pope’s work on The Iliad. When Pope or any translator poet felt himself “deficient” in understanding, he would make “minute inquiries into the force of words.” Chapman, for example, besides Pope, clearly worked this way. The aim of these efforts is to provide, as Johnson, sought, the best poem in English. The result of translation in the context I have been discussing is, as Johnson notes, a way to enrich both languages just as Pope’s translation of Homer “tuned the English tongue.” Pond puts it this way: “it is in the light born of this double current that we look upon the face of the mystery unveiled.” Pound says that his translations of Cavalcanti are not line by line by rather “embody in the whole of my English some trace of that power which implies the man.” Clearly the notion of translation here is far different than what the average person thinks.

The French poet, Paul Valery, in his The Art of Poetry, writes that in translating Virgil he wanted to change parts for he felt a merging with the author: translating was creating, he felt. In a similar way, in our own time, Pulitzer Prize winning poet and translator Charles Simic writes: “translation is an actor’s medium. If I cannot make myself believe I am writing the poem I’m translating, no degree of aesthetic admiration for the work will help me.” Judith Hemschemeyer, who translated perhaps the greatest poet of the century, Anna Akhmatova, describes a slow process of first getting a basic sense and then working to duplicate various effects depending upon what she felt the main strength of a particular poem to be. And well known American poet Galway Kinnell describes, in his preface to Villon’s poems, how “one can be impeccably accurate verbally and yet miss the point or blur the tone quite badly….I wanted to be ‘literal’ in another sense. I wanted to be more faithful…to the complexities of the poetry, both to its shades of meaning and its tone. At the same time I wanted the English to flow very naturally. Therefore I avoided transferring ‘meanings’ from one language directly into another.” Kinnell goes on to say he attempts to “internalize” the French: I would not merely be changing language into language but also expressing what would have become to some extent my own experiences and understandings.” If that seems strange, remember that whenever we read a poem in our own language we bring our own experiences, contexts, and notions to the text, and they interact to form a unique experience called the poem. One could argue– and many critics and linguists today do so– that we translate even as we read within our own language. reading Kinnell’s poems and Kinnell’s translations involves similar activity, and not unlike what we would do when reading Villon in the original. So what is Villon’s poem? As read by a French scholar? a French poet? a good reader of French? a bad reader? Do the poems exists in some absolute Platonic place where all the meanings and effects are intact? Do they exist in individual reader’s responses? Somewhere in between? These are precisely the issues a translator and a reader of translations must face. “It is because it is impossible that translation is so interesting,” wrote William Matthews who has translated Ovid, Horace and Martial.

In a letter about the nature of poetry to his brother, Gherardo, Petrarch wrote of the Biblical poetry that they “never have been, or could be, easily translated into any other language without sacrificing rhythm and meter or meaning. So, as a choice had to be made, it has been the sense that has been more important. And yet some trappings of metrical law still survive, and the individual pieces are what we still name verses, for that is what they really are.” Still, unsatisfied finally with that, Petrarch wrote his own sequence of Salmi Penitenziali in a single year in imitation of the Biblical psalms, but using phrases and ideas from the originals. In the “Preface” to his “Familiar Letters” Petrarch wrote that “The first care of the poet is to attend to the person who is the reader; this is the best way to know what to write and how to write it for a specific audience.” In a sense he prefigures Johnson’s concern, cited above, that the purpose of poetry is to be read.

How, then, to restore poetry’s original sense of freshness, of movement, and yet take into account a modern audience is always the issue. Translators like David Slavitt, with Ovid and Virgil, and William Matthews, with Martial and Horace, have magnificently transplanted these poets to our own times so that they seem to come alive, filled with their own concerns, but as they would speak in our own age, as Johnson had wanted. Matthews, for instance, adds current references, Slavitt’s Virgilian Eclogues are as much interpretations as translations. In other words, they have considered the contemporary reader, as Petrarch urged, along with the meaning and rhythms. This is precisely the example of Horace and of Pope. As Johnson wrote of Pope’s Homer: “To a thousand cavils one answer is sufficient: the purpose of an author is to be read, and the criticism which would destroy the power of pleasing must be blown aside.”

Literary translation comes close, as Pope suggests in a letter about his Imitations of Horace, to the notion of imitation. One anonymous wrote that Pope’s versions were “bound hand and foot and yet dancing as if free.” Earlier, Ben Jonson had defined imitation in his Timber as merely a poem loosely based on another poem. Dryden in his “Preface” to his translation of Ovid, then defined three kinds of relationship a poet could have to a prior text. “Metaphrase” for Dryden was a slavish, “word by word” account. “Paraphrase” was a “translation with latitude” that kept the original meaning but often with “amplification.” “Imitation,” on the other hand, meant, for Dryden, a process where the “translator (if now he has not lost that name) assumes the liberty, not only to vary words and sense, but to forsake them both as he sees occasion; and taking only some general hints from the original, to run division on the groundwork, as he pleases.” This is precisely the sort of thing Robert Lowell does in his Imitations from various poets, and what Pound does in his “Homage to Sextus Propertius,’ a sequence of loosely translated lines rearranged into a sequence of totally new poems. And it is related to what Stephen berg does in gathering images, tones and lines from Anna Akhmatova in his With Akhmatova at the Gate . Dana Gioia has written an essay describing how Donald Justice makes use of various lines, poems and forms of previous poets in over a fourth of his own poems.

We’ve become so used, in our own time and place, to valuing the new and the different above all else, that we have lost sight, in our own art of poetry with its rich tradition, of, as Roethke says in the title of a revealing essay, “How to Write Like Someone Else.” Indeed, poets through the ages have learned to write by imitation, from Catullus adaptations of Callimachus, Horace’s borrowings from Lucilius, Petrarch’s use of Dante and Cino di Pistoia, Wyatt and Surrey’s use of Petrarch, and so on. Pope in fact said he turned to imitation to tighten his own verse and to find a voice to say things he was not ready to speak in his own voice. Petrarch, an early champion of learning from the past, writes in a letter to his friend Boccaccio: “An imitator must see to it that what he writes is similar, but not the very same; and the similarity, moreover, should not be like that of a painting or statue to the person represented, but rather like that of a son to a father, where there is often great difference in the features and members, yet after all there is a shadowy something– akin to what the painters call one’s air–hovering about the face, and especially the eyes, out of which there grows a likeness…. [W]e writers, too, must see to it that along with the similarity there is a large measure of dissimilarity; and furthermore such likeness as there is must be elusive, something that it is impossible to seize except by a sort of still-hunt, a quality to be felt rather than defined…. It may all be summed up by saying with Seneca, and with Flaccus [Horace] before him, that we must write just as the bees make honey, not keeping the flowers but turning them into a sweetness of our own, blending many different flavors into one, which shall be unlike them all, and better.” Imitation, in other words, is creation: just taking a glance at what Samuel Johnson does to Juvenal in his “Vanity of Human Wishes” or what Frost does with Virgil’s Georgics in his North of Boston the Greek Anthology in A Witness Tree ought to show us how one can learn from the past and still be original. Curiously, Frost gave a January 1916 lecture called “The discipline of the Classics and the Writing of English” which extolled imitation. One can see how James Wright’s middle poems were influenced by his reading of Lorca, Jiminez, Neruda and various imagistic poems from China and Japan. In fact, a glance at W.S. Merwin’s poems in The Lice (1967) and the translations he was doing at that time show an incredible similarity of the type Petrarch describes. Of course, sometimes imitation is very close to the original: in fact, one translation of Merwin’s , “The Creation of the Moon” derived from a South American Indian tale is almost rendered step by step in in The Lice but with a different ostensible subject.

Even more loosely, we can see a number of influences: Kunitz, Horace and Robinson on James Wright; Greek and Roman epigrams on Linda Gregg and Jack Gilbert; Vallejo, Rimbaud and the beats on Tomaz Salamun. Longinus, the Roman critic wrote: “Emulation will bring those great characters before our eyes, and like guiding stars they will lead our thoughts to the ideal standard of perfection.” Perhaps one of the greatest examples is the way Petrarch borrows the idea of creating an evolving self in a sequence of poems from Horace’s Odes and his sense of how to address the reader from Cicero’s letters. Ultimately the point here is that poets learn to advance their craft by reading other poets from other ages and other cultures, adapting impulses, lines, forms and ideas to their own times. Not to read, not to “emulate,” is to isolate one’s art, to leave it static.

.

IV

My personal history of ideas by poet-translators on their art is a far ranging one that extends from the Romans like Catullus who saw it as a “combat” with the original, to poets like Petrarch and Samuel Johnson who judged a version by its effect in the so called “target language,” to Robert Lowell’s and Alexander Pope’s loose “imitations.” I know that some of these practices would startle if not horrify most of my language teachers. Yet even a respected academic like Wilhelm Humbolt, in his introduction to his translation of Aeschylus’s Agamemnon, says: “the more a translation strives toward fidelity, the more it ultimately deviates from the original, for in attempting to imitate refined nuances and avoid simple generalities it can, in fact, only provide new and different nuances.” This is perhaps why a poet like Jane Hirshfield, also a translator from Japanese, writes: “Translation’s very existence challenges our understanding of what a literary text is.” I think what has intrigued me about the various possibilities of various kinds of translation is precisely that challenge; it offers a way to understand my native language better, to pay more conscious attention to kinds of detail that I approach on a more subconscious level in writing my own poems, and to appreciate some relationships between my own poems and those of poets in another language with whom I have found a kindred spirit.

For my own part, I have done three separate and very different translation projects that I would like to describe for what light they might cast on the the poet as translator. I felt that each poet’s poems demanded a different approach. Perhaps what links these three very different projects is Milan Kundera’s notion, in Testaments Betrayed, of the importance of the original author’s “personal style.” In many ways he extends Humbolt’s theory when her says that “every author of some value transgresses against ‘good style,’ and in that transgression lies [his] originality. The translator’s primary effort should be to understand that transgression.” For me this has meant reading everything, from letters to journals to work in other genres, to the author’s own translations of other writers’ works, and to the author’s own contemporaries, in an attempt to get to the source of his style, the structure of his mind. The results have been variously: a fairly traditional approach, a radical transformation of the original, and a collaborative project.

First, the traditional approach. Several years ago I stumbled across a book of last poems by Cesare Pavese in a bookstore in Firenze, poems not then availabe in English, and very different from the William Arrowsmith versions I knew. This book, his last poems before he committed suicide, contains a number of poems in narrow lines where the metamorphic aspect of his earlier work is much intensified. A number of these poems of “Disamore,” “Disaffection” or “Lost Love,” as it might literally or figuratively be translated, identify the land of northwest Italy, especially from Torino to Genoa with a woman, and that land as variable, enticing, dangerous, beautiful, forbidding and distant.

Most translators translate one section of these last poems, originally published in a pamphlet, as “Death Will Come and It Will have Your Eyes.” I translate the title as “Death Will Come and She Will have Your Eyes.” This small difference suggests a huge difference in what Pavese is trying to do. The whole section, in fact, deals with a woman or women who potentially betray him—leading up to his suicide reportedly after his rejection by an American actress. The personification, using “she” rather than “it” is warranted first by the way he personifies other things such as the land, which he sees as feminine, in earlier sections from this book. (While “morte” is technically feminine in Italian, this of course does not carry over into English, though one wonders if Pavese, so careful with images, might have felt this more than we do.) For example, in one poem in this book he writes: “You are the land and death.” In another he says the woman is a “clump of soil.” In another section he is even more direct in linking womanhood to death, something he does in his journals where he says that one kills himself for the love of a woman, “any” woman because of the way the self is humiliated by all women. Obviously, Pavese’s attitude towards women throughout his poems could have benefited from serious counseling.

In any case, my version reads:

Death will come and she will have your eyes.–

this death that accompanies us

from morning to evening, sleepless,

deaf, like an old remorse,

or an absurd vice. Your eyes

will be one empty word,

a hushed cry, a silence.

Things you see each morning

when you alone gather yourself

into a mirror. O dear hope

when will we ever know that

you are life and you are the empty day.

For every death looks the same.

Death will come and she will have your eyes.

It will be like giving up a vice,

like seeing in a mirror

the face of death come to the surface,

like listening to closed lips.

We will descend to the abyss silently.

Personifying death this way also makes the image of seeing death, the woman, in the mirror, more powerfully, for in many ways the idea of a deadly woman took over and controlled his own identity. So the Pavese project has been one where the basically accurate translation tends to emphasize Pavese’s peculiar humanizing of his landscapes more than other translations.

I should also add that these later poems have an entirely different rhythm than his earlier ones: there are quicker turns and the emphasis is more on words and their placement in the line than on phrases and sentences as in the earlier poems. I feel, because of the rhythm of thinking in the original, that, as much as possible, the original word order should be kept. In translations of earlier poems, on the other hand, I have placed more emphasis on the phrase and image order, for it is in those poems that Pavese practices his theory of the “image narrative.” So for example, my last line in “Death Will Come” reads “we will descend into the abyss silently” rather than the more normal American English order, “we will descend silently into the abyss.” The word, silently (“muti”), comes as a kind of afterthought in the syntax, and yet its place at the end of the line also emphasizes the relationship between silence and death.

The effect on my own poems, if I can judge that, has been first of all an increase in the use of personification, and related to that, a more functional use of landscape. I think I have also noticed a greater attention to different effects of lineation. And as far as understanding Pavese goes, I have gained a more sympathetic understanding of the pathology of his torment.

The second project is not really translation at all, but rather “Poems based on Petrarch,” where I have taken an entirely other approach, using the originals as take off points for what might be likened to jazz riffs. I have in mind the way Coltrane uses a few bars of “Bye Bye Blackbird” in his Swedish date and then takes off into the stratosphere for 13 minutes until we are so far afield all we sometimes hear are a few of the original notes in various patterns. In a way I am following Petrarch’s own advice when he writes in a letter to his friend Boccaccio: “An imitator must see to it that what he writes is similar, but not the very same; and the similarity, moreover, should not be like that of a painting or statue to the person represented, but rather like that of a son to a father, where there is often great difference in the features and members, yet after all there is a shadowy something– akin to what the painters call one’s air–hovering about the face, and especially the eyes, out of which there grows a likeness…. [W]e writers, too, must see to it that along with the similarity there is a large measure of dissimilarity; and furthermore such likeness as there is must be elusive, something that it is impossible to seize except by a sort of still-hunt, a quality to be felt rather than defined…. It may all be summed up by saying with Seneca, and with Flaccus [Horace] before him, that we must write just as the bees make honey, not keeping the flowers but turning them into a sweetness of our own, blending many different flavors into one, which shall be unlike them all, and better.”

I suppose another model for me was the way Ben Jonson had defined imitation in his Timber as merely a poem loosely based on another poem. Besides, for me there was a problem of the quality of the English version, for even by the time of Shakespeare’s mocking of Petrarch in “My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun” many of Petrarch’s fresh images and comparisons had already become clichés. This was a problem I experienced with my first versions of Petrarch which were standard conservative translations. These early versions led me to realize that I wanted a sense of what I felt Petrarch might sound like if he wrote today in America. In this context I think of what Pound does in his “Homage to Sextus Propertius,’ a sequence of loosely translated lines rearranged into a sequence of totally new poems and what Jo Shapcott does in Tender Taxes, based on Rilke’s French poems, which, as she says, “re-imagines Rilke’s brief and fugitive lyrics as English poems.”

Here, for example, is Petrarch’s #234. ‘O cameretta che già fosti un porto’, literally translated:

O little room that sometimes served as a port

In these fierce daily storms of mine,

You are the fount, now of my nightly tears,

Which, because of the shame I feel, I hide by day.

O little bed, that used to be a comfort and a rest

In many trials, from what doleful urns

Love bathes you with those hands of ivory,

So cruel to me alone, so unjustly!

I flee not only from seclusion and my rest,

But flee myself and my thoughts even more,

Which used to raise me in flight as I followed.

And now for asylum, I seek out the crowd,

My hated foe — who would believe that?

I am so afraid of finding myself alone.

(my translation)

My riff, “The Exile,” tries to extend the mood of the poem, keeps some allegiance to the setting, but radically changes the images, making them more surreal. I suppose I had in mind what Dryden called “imitation” and what Pound logopoeia, “the dance of the intellect among words. It is admittedly a far cry from the original, in fact I would really consider it more of an original poem that, in Eliot’s phrase, “steals” from the original. Here, then, is my “riff”-

Grief frames the doorway to that room I used to call my port

against whatever storms came careening down my street,

that room with its memories now crumpled on a table, a fleet

of hopes wrecked by words that regret what they alone distort.

Thorns fill the bed. A taunting night shakes its keys to closets

of desire I can no longer open. Who sleeps there, indiscreet

rival, while I flee his shadows that loiter like a disease

which waits for a soul to pummel, a love to perfectly thwart?

The doorknob of the night is always turning, but it is myself I flee–

my dreams, my rhymes, that lifted me towards a heaven

I thought was the love these words might finally create.

Maybe now I’ll hide in those city crowds I’ve come to hate

since I can no longer face myself, no longer be alone.

Longing rings the doorbell, but the house is empty.

My first idea was how to make this remarkable poet and influence fresh again, more contemporary. So there’s the doorbell is a contemporizing effect, and the doorknob, and the colloquial American English in general. But in all of them I have kept the original rhyme scheme, or one of the schemes, using a lot of slant rhymes. I also loosened the line from his pretty strict classical 11 syllable Italian line, but within those constraints I was often thinking through Petrarch’s mind as I understood it, especially after reading all the 365 poems in his conflicted book about Laura, his Ciceronian and Familiar letters, his other poems and prose and several biographies and critical works.

The poems vary considerably in what they owe to the original, because my ultimate aim was what I could apply to my own work. As I worked with more of his poems I saw much in his life and times similar to my own, and so I began to absorb that personality. Oddly, then a great number of these poems are in effect more autobiographical than my other poems from about 1993 on. This project effected a greater sense of the possibilities for contradictions and arguments within the evolving movement of my own poems, a move also towards more concise poems than I had been writing, a greater sense of the odd and sudden twists and turns metaphors can take, and the way a controlling metaphor can move in and out of a poem’s surface. I’ve done about seventy poems, mostly sonnets, with a few canzoni, and am probably done with it for now.

My third translation project is a collaborative effort with two other American poets, Susan Thomas and Deborah Brown, with occasional help from a few of our friends. In our versions of Giovanni Pascoli, a turn of the last century poet who spent his last years in rural Barga, in northwest Tuscany, we have used John Hollander’s notion of finding an analogue in English poetry to use as a kind of base. (As with the Pavese and Petrarch, I have visited Pascoli’s home and favorite haunts to gain a further feel for the landscape that is so important to him.) Pascoli, by the way, was a terrific influence on Pavese. Just as Nabokov found an analogue for his translation of Pushkin in Andrew Marvell, as part of our procedure, we found an analogue in a combination of Hardy and Frost, that is, a voice that is at once rustic and cosmopolitan, melodious and rough, minute in its natural observations and ready to imply larger analogies. We have not kept strictly to Pascoli’s format, never the rhymes which his rustic syntax allows him to sound more natural in Italian, though we have tried to duplicate the inner form, the appearance on the page and many of the sound effects.

Our procedure, after deciding we wanted an accurate translation that also conveyed the mood and tone– was for one of us– this varied poem to poem — to provide a version to work on. Then the other two would offer comments, suggestions, sometimes radical rephrasing. This was mostly done by email. A number of problems surfaced immediately. For one, Pascoli writes in a particular dialect from the mountains of northwest Tuscany above Lucca. A number of words had to be deciphered contextually through the meanings of the poem in question, its companions and through the online version of the poems that also contained a useful concordance. Stylistically, Pascoli often drops part of a sentence, uses pronouns in an ambiguous way to extend meanings, and puns in sometimes very subtle ways (both verbally and visually). As with Pavese, I felt the word order with its rhythm and lineation was crucial. Some of his references are to specific places near Barga, and to particular folk events and sayings. He also has a habit of linking clauses together by semicolons to suggest a kind of linking of the particulars of a scene in a kind of image narrative that may have later influenced Pavese’s theory of the “image story.” His poems range from dialectic sequences of brief lyrics about rustic life to odes and other longer poems, and then later in his career to political poems and poems based on classical and mythic themes, on artists and other famous figures.

One example of the problems of translation here stems from his extensive knowledge of astronomy and mythology. For example, one of his most interesting sequences is “The Last Voyage,” a narrative of Odysseus wanderings after the Odyssey to plant an oar where Poseidon is not known, certainly a sequence influenced by Tennyson’s “Ulysses.” Susan rendered the opening poem’s lines 3-5 as:

Because of an error made on land,

He was exhausted and foot weary,

Supporting an oar on his strong shoulder.

Now the word for shoulder is “omero” which, capitalized, is also “Homer.” The poem itself is a carrying forward of Homer: should we try to account for this pun? Would the phrase “Homeric shoulder” work? The adjective for shoulder is “grande” which can mean here “big” or “strong.” Someone even suggested “epic shoulder” which we rejected. Also, the “error made on land” is that he is lost — (the root of “error” in English and the Italian original here is to wander– as in Spenser and Milton, for example). Lines one and two had referred to Ulysses as the great navigator– on sea. So, for now, our committee of three has settled on the following, also changing the word order to reflect the original:

Because he had lost his way

He was exhausted and foot-weary,

Carrying, on his strong Homeric shoulder, an oar.

Even the title of the poem, “La Pala,” or “blade,” though, poses problems. “Pala del remo” is the blade of an oar, but the oar here is mistaken for a harvest flail, and in the second poem “L’Ala” (literally, “wing” or even “oar blade”) the oar is perceived as a wing. So should we render the two titles as “The Oar as Flail” and “The Oar as Wing”? We are still wrestling with the possibilities.

With references to constellations and stars we have consistently described them as the animals and figures they were seen as in ancient times because Pascoli seems to be using them this way. For example, Deb’s literal rendering of one section of a later poem in the sequence would yield:

It is time to plow the field, not the sea,

from which you can see not even

a handful of the seven stars.

It is sixty days till the sun returns,

Until Ursa Major, the stars that guide you,

will return. By then the breeze is sweet,

the sea is calm, the shining Bootes will be visible.

The seven stars are possibly the Pleides according to an Italian editor’s notes, but most likely the big dipper, Ursa Major, the great bear because Bootes, after all, is the hunter who follows after her. Indeed, the handful of stars is what is probably referred to as the tail of the bear — or the handle of the dipper. Actually, Pascoli uses the word “Carro” (capitalized) for Ursa major which is its astronomical meaning, but its more common meaning is cart, and so the tail of the bear is also the cart’s handle and the dipper’s handle. The association with the cart is important because it relates to the plowing image. There is a kind of furiously quick web of associations here that is probably impossible to translate. Here’s our version:

It is time to plow the field, and not the sea,

From which you can not even begin to see

A handful the seven stars in the Great Bear.

It is sixty days till the sun will return,

Until the Bear, your guiding constellation,

Will return. By then the breeze is sweet, the sea

Calm, the brilliant hunter will be visible….

There is an interesting play between what can and can’t be seen, between finding one’s way and being lost. And this version tries to maintain some of the traditional 11 syllable line length that Pascoli deploys. We have kept “handful” to suggest both the plowed earth and the handle of the cart. Finally, turning the constellations into the figures they represent gives, we hope, a greater sense of visual drama.

Working on this collaborative effort has been immensely rewarding for it has the advantage of having different minds, while adhering to the same general poetics, offer and discuss various alternatives. The result has been a deeper understanding of the process of translation, and of the inner workings of Pascoli’s poetic mind, and also possibilities for using myths in our own poems. And we have been able to see how Pascoli’s descriptive poetry is later adapted and transformed into a more metamorphic vision by Pavese: in other words, we have been able to see a kind of translation between poets of the same language which has in turn influenced how we read our own influences.

The American Pulitzer Prize winning poet, Charles Simic, writes that “Lyricism, in its true sense, is the awe before the untranslatable.” I suppose it is that sort of lyricism that these three projects aim for. Obviously, too, I have been using American rather than British English, a difference radically brought home to me this past September at Vilenica where I worked on a couple of poems by a Slovene poet with a British poet translator, Stephen Watts, the Slovene translator, Ana Jelnikar, and the poet herself. Several times Stephen and myself had very different phrasing. Each of our choices, I believe, was appropriate to our audiences back home. I was reminded of the American teacher who had his class translate a sentence, “The evening passed,” from an English novel, and one student rendered it as “It got late.” And it has– so I’ll end here.

—Richard Jackson

Some Useful Sources

Arrowsmith, William and Roger Shattuck, eds., The Craft and Context of Translation: A Critical Symposium. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1961.

Baker , Mona, ed., Encyclopedia of Translation Studies. London: Routledge, 1998.

Barnstone ,Willis, The Poetics of Translation. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

Belitt, Ben. Adam’s Dream: A Preface to Translation. Grove, 1978. Interviews, essays, introductions on a variety of problems and poets.

Brower, Reuben, Mirror on Mirror: Translation, Imitation, Parody. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974

_____, ed., On Translation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1959. This landmark anthology includes Bayard Quincy Morgan’s critical bibliography of works on translation (from 46 BC. to 1958)—an essential historical survey of the topic.

Gass, William. Reading Rilke: Reflections on the Problems of Translation. Knopf, 1999. A well thought out, book length account of what it means to translate an author, his life, his work, his being.

Gentzler, Edward, Contemporary Translation Theories. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Graham, Joseph F., ed., Difference in Translation. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985.

Grahs, Lillebill and Gustav Korlen, eds., Theory and Practice of Translation. New York: Lang, 1978.

Hawkins, Peter and Jacoff, Rachel. The Poet’s Dante: Twentieth Century Responses. Farrar, Strauss, 1999. Essays by numerous essential poets such as Pound, Yeats, Eliot, Montale, Lowell, Auden, Merwin, Pinsky, Doty, Hirsch and many others.

Hirschfield, Jane. Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry. Harper Collins, 1998. This terrific book has a great essay on translation.

Kelly , Louis G.. The True Interpreter: A History of Translation Theory and Practice in the West. Oxford: Blackwell, 1979

Raffel, Burton, The Art of Translating Prose, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994.

_________, The Art of Translating Poetry, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1988.

_________, The Forked Tongue: A Study of the Translation Process. Hawthorne, NY: Mouton de Gruyter, 1971.

Schulte, Rainer and Biguenet, John. Theories of Translation: An Anthology of Essays from Dryden to Derrida. University of Chicago Press, 1992. Includes major works by Goethe, Rossetti, Benjamin, Pound, Nabokov, Paz and others; the best single source of theory.

Schulte, Rainer and Biguenet, John. The Craft of Translation. University of Chicago Press, 1989. Excellent practical essays, many being introductions, on translating writers such as Celan, Eich, Japanese Poetry, medieval works, and some theory.

Steiner, George, After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation. London: Oxford University Press, revised edition 1993 (original edition 1975).

Warren, Rosanna, ed., The Art of Translation: Voices from the Field. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1989.

Weissbort, Daniel, ed., Translating Poetry: The Double Labyrinth. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1989

Wechsler, Robert. Performing Without a Stage: The Art of Literary Translation. Catbird Press, 1998. General introduction to major issues.

/

Other Sources

Some examples of Adaptation include: Jo Shapcott, Tender Taxes (Faber and Faber, 2001); Stephen Berg, Oblivion (Illinois, 1995) and With Akhmatova at the Black Gates (Illinois, 1981); Robert Lowell, Imitations (Farrar, Strauss, 1961).

Two excellent examples of various versions of two major poets, from translation to imitation are:

- Dante’s Inferno: Translations by 20 Contemporary Poets, ed. Dan Halpern, Ecco Press, 1993. Widely different approaches by Heaney, Strand, Kinnell, Graham, Plumly, Mitchell, Williams, Wright, Clampitt, Forche, Merwin, Digges, Hass, etc.

- After Ovid: New Metamorphoses, ed, Michael Hofmann and James Lasdun, Faber and faber, 1994. Everything from strict translation to tangential relationship is represented in versions of Ovid’s Metamorphoses by Hughes, Graham, Fulton, Pinsky, Boland, Carson, Muldoon, Simic and others.

The Nov/Dec 2002 Poets and Writers magazine has a complete section on translation.

See also the comprehensive web site sponsored by P.E.N. International.

There is a terrific Manual For Translators with bibliography and resources at http://www.pen.org/translation/handbook1999.html#_Toc452369688

/

/

Barthes, in his famous essay “

Barthes, in his famous essay “

What had happened? The room seemed really tiny and the smell much less mildewy than before. There were hooks on the wall to hang a broom and mop on. In one corner, two buckets. Along another wall, a shelf with sacks, boxes, pots, a vacuum cleaner, and, propped against that, the ironing board. How small all those things seemed now—he’d hardly been able to take them in at a glance before. He moved his head. He tried twisting to the right, but his gigantic body weighed too much and he couldn’t. He tried a second time, and a third. In the end he was so exhausted that he was forced to rest.

What had happened? The room seemed really tiny and the smell much less mildewy than before. There were hooks on the wall to hang a broom and mop on. In one corner, two buckets. Along another wall, a shelf with sacks, boxes, pots, a vacuum cleaner, and, propped against that, the ironing board. How small all those things seemed now—he’d hardly been able to take them in at a glance before. He moved his head. He tried twisting to the right, but his gigantic body weighed too much and he couldn’t. He tried a second time, and a third. In the end he was so exhausted that he was forced to rest.