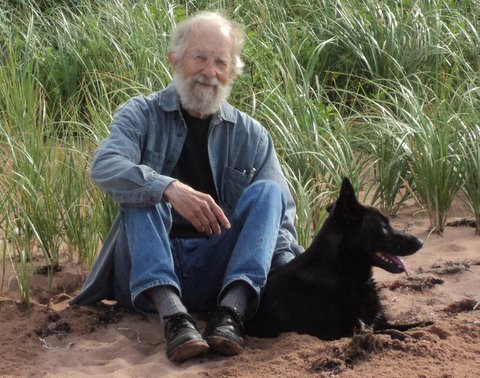

John Malcolm Brinnin 1916-1998

John Malcolm Brinnin 1916-1998

Brinnin published five books of poetry between 1942 and 1956 but his work was not embraced by a large audience. It’s true that Brinnin’s meanings are not easily grasped on first reading. Norman Rosten, who published the Communist review The New Masses, complimented Brinnin by calling him a “poet’s poet” (that kiss of death in terms of popularity) but explained his decision not to publish Brinnin’s work in the magazine by saying, “You, being a fastidious worker of images and rhythms, are not too easy to grasp. A compliment, really. But the revolution must go on – even with lousy poetry.”

—Julie Larios

Imagine this scene in Florida’s Key West: the sun beats down on a white sand beach, a hot breeze blows the palm fronds, and six middle-aged men sit around a table playing anagrams. They rearrange the letters of words to make new words; they argue about the rules; they yell a lot. If it sounds to you like these men should be Morty Seinfeld and Frank Costanza and their friends, I agree. But the group consists of composer Leonard Bernstein, journalist John Hersey, and poets John Ciardi, Richard Wilbur, James Merrill and John Malcolm Brinnin.

A Favorite Pastime Among the Literati of Key West

A Favorite Pastime Among the Literati of Key West

Three or four times a week, depending on how many of them were in town, these men played anagrams and poker together in Key West. Ciardi was the most aggressive of the group and, according to his biographer, expected to win every game. Bernstein, according to the same account, insisted on his own rules. They were all successful and well-known artists – all, that is, but John Malcolm Brinnin, who was described by the literary critic Phyllis Rose this way: “Even some of us who saw a good deal of John Malcolm Brinnin in his later years forgot he was a poet….John was known to us, his friends, for the high drama of his eye glasses, massive horn affairs that were as much a product of his wit and conscious choice as his courtesy, his conversation, his skill at anagrams. A lot of poetic spirit went into his self-presentation.”

Of the several poets presented in the Undersung series here at Numero Cinq, there is not another one among them who could be said to have had his or her poetic reputation subsumed by self-presentation, and I think Rose chose the words of her reminiscence carefully. In it, she implies both affection for Brinnin and criticism of him – she enjoys his elegance and his contribution to the party atmosphere (“He dressed so well one always looked forward to his getup as part of the fun of a party….”) but chastises him for his “conscious choice” of style over substance. To subordinate your talent to self-presentation (though some people might call self-presentation an art in itself) is a puzzle. What Rose seems to be saying is that Brinnin was – like a good formal poem – elegantly composed, but also – like a bad poem – overfabricated.

Well, we don’t have to judge poets by their self-regard, nor by how well they dress. We can choose to judge them by the poems they wrote, and Brinnin’s work more than measures up. It’s true that the poems in his first book (The Garden is Political, 1942) were called “mannered” by one critic who was, most likely, eager for the diction of poetry in the 1940’s to to be looser and more modern. It’s true, also, that Brinnin’s work does not sound loose; his language is denser, more opaque than the broken lines of prose that became more and more popular as the 20th-century progressed. Not many authors survive the curse of being called old-fashioned. But whatever the reason for the mannerisms some critics accused him of, Brinnin’s poetry pleases me in the same way Shakespearean monologues and sonnets please me: they’re the product of someone with large things to say, someone using his or her intelligence to put pressure on the English language to be simultaneously truthful and beautiful.

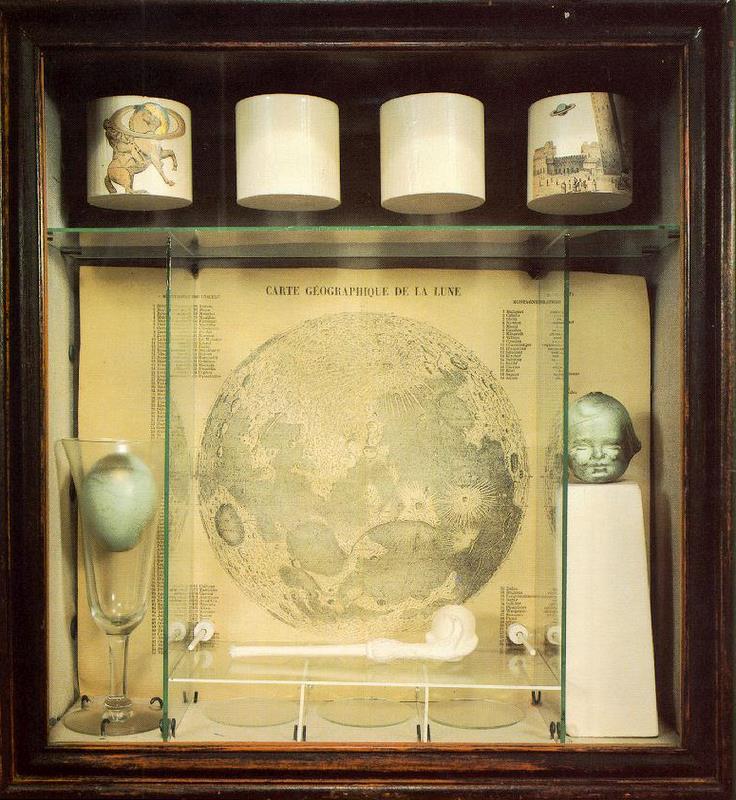

La Creazione degli Animali

Here that old humpback Tintoretto tells

Of six day’s labor out of Genesis:

Swift from the bowstring of two little trees

Come swans, astonished basilisks and whales,

Amazed flamingos, moles and dragonflies,

to make their lifelong helpless marriages.

Time is a place at last; dumb wonder wells

From the cracked ribs of heaven’s gate and hell’s.

The patriarch in that vicinity

Of bottle seas and eggshell esplanades

Mutters his thunder like a cloud. And yet,

much smaller issues line the palm of God’s

charged hand: a dog laps water, a rabbit sits

grazing at the footprint of divinity.

From the largest moments of that poem (Heaven, Hell, Time, divinity) to the smallest (a dog lapping water, a rabbit at the feet of God) Brinnin offers up the “dumb wonder” a person feels in the face of such an ambiguous world, and in the presence of work produced by a master artist. The poem follows some of the rules of a sonnet – fourteen lines, with a slight turn or refocus after the eighth line. But Brinnin is no stranger to adapting the rules to his own purpose – the rhymes assert themselves clearly but without establishing a conventional pattern (ABCA/DEAA/FGHG/HF.) The couplet which usually closes a conventional Elizabethan sonnet is buried mid-poem (“Time is a place at last; dumb wonder wells / From the cracked ribs of heaven’s gate and hell’s.”) The full rhyme of “vicinity” and “divinity” still chimes loudly despite being separated by four other rhymed lines – not an easy task.

Tintoretto – la creazione degli animali

Tintoretto – la creazione degli animali

Brinnin published five books of poetry between 1942 and 1956 but his work was not embraced by a large audience. It’s true that Brinnin’s meanings are not easily grasped on first reading. Norman Rosten, who published the Communist review The New Masses, complimented Brinnin by calling him a “poet’s poet” (that kiss of death in terms of popularity) but explained his decision not to publish Brinnin’s work in the magazine by saying, “You, being a fastidious worker of images and rhythms, are not too easy to grasp. A compliment, really. But the revolution must go on – even with lousy poetry.” Rosten rightly said that “the question of ‘popular’ understanding is very important to a revolutionary magazine.”

So Brinnin was not a poet of the people; his poems are layered and dense and must be worked out slowly. I suspect hearing them aloud would untangle them more quickly than reading them on the page. In fact, when I read Brinnin, I often imagine someone reading his poems to me – someone like Ian McKellen or John Gielgud. Again, his work has a Shakespearean elegance. Being read aloud, the complications of syntax might settle down, while the musicality of them would shine. Brinnin’s sentences are long, which ups the level of difficulty; the verbs sometimes hide within the verbiage, so their narrative thrust – that is, their “sense” — is not immediately discernible. Brinnin’s words will never make their way onto a revolutionary’s placard, and clarity is not their goal. Take this example:

A River

A winkless river of the cloistered sort

Falls in its dark habit massively

Through fields where single cattle troll their bells

With long show of indifference, and through

The fetes champetres of trees so grimly bent

They might be gallows-girls betrayed by time

That held them once as gently as Watteau.

Electric in its falling, passing fair

Through towns touched up with gilt and whitewash, it

Chooses oddments of discard, songs and feathers

And the stuff of life that must keep secrets

Everlastingly: the red and ratlike curios

Of passion, knives and silks and embryos

All sailing somewhere for a little while.

The midnight drunkard pausing on the bridge

Is dumbstruck with a story in his eye

Shuttling like his memories, and must

Outface five tottering steeples to admit

That what he sees pass under him is not

Mere moonlit oil and pods of floating seed,

But altogether an astonishing swan.

The river, I mean, for all is riverine,

Goes slowly inward, as one would say of time,

So it goes, and thus proceed to gather in

The dishes of a picnic, or the bones

Of someone lost contesting with the nations,

Glad in the wisdom of his pity to serve

Though the river’s knowledge, whelming, overwhelms.

This isn’t subject/predicate/object territory; a sadistic high school English teacher could make her students suffer by requiring students to diagram the sentences of it. Each seven-line stanza is a single sentence, nouns often sit quite a way from the verbs they depend on, and lush dependent clauses make readers push to figure out exactly where the sentence goes. The effect of this poem is similar to a cubist painting; like Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase,” we see the movement before we quite understand the figure; we grasp the gestalt before we deconstruct the individual lines. From “fetes champetres” on, we know we’re in for some work. Questions pile up: In what way was the artist Watteau gentle? What does it mean to say that a river goes “slowly inward”? What does the river represent – to me, to other readers – and what did it represent to Brinnin himself? Who exactly, or inexactly, is “lost contesting with the nations”?

Answering or not answering these questions is a matter of personal preference; I’m comfortable being “riverine” and flowing past some of the difficulty, then following up later with a little research. Without much trouble I find images of Watteau’s paintings and realize that many of his people face away from us, just as “the stuff of life that must keep secrets.” I can ponder that for awhile, and isn’t pondering part of the pleasure of poetry? I read the best of Brinnin’s poems again and again, and I understand them better each time; I find new beauties each time. I’ve read the following poem several times and still have questions; to my mind, that’s a plus.

Rowing in Lincoln Park

You are, in 1925, my father;

Straw-hatted, prim, I am your only son;

Through zebra-light fanwise on the lagoon

Our rented boat slides on the lucent clam.

And we are wistful, having come to this

First tableau of ourselves: your eyes that look

Astonished on my nine bravado years,

My conscious heart that hears the oarlocks click

And swells with facts particular to you –

How France is pink, how noon is shadowless,

How bad unruly angels tumbled from

That ivory eminence, and how they burned.

And you are vaguely undermined and plan

Surprise of pennies, some directed gesture,

Being proud and inarticulate, your mind

Dramatic and unpoised, surprised with love.

In silences hermetical as this

The lean ancestral hand returns, the voice

Of unfulfillment with its bladelike touch

Warning our scattered breath to be resolved.

And sons and fathers in their mutual eyes,

Exchange (a moment huge and volatile)

the glance of paralytics, or the news

Of master-builders on the trespassed earth.

Now I am twenty-two and you are dead,

And late in Lincoln Park the rowers cross

Unfavored in their odysseys, the lake

Not dazzling nor wide, but dark and commonplace.

Brinnin was perhaps best known to his generation as “the man who brought Dylan Thomas to America.” As head of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association Poetry Center (now known as the 92nd St. Y) from 1949 to 1956, Brinnin founded a series of poetry readings that included some of the best known poets in America and Britain. He acted as Thomas’s “agent” in America, scheduling readings and arranging for places Thomas could stay. During the Welsh poet’s last cross-country tour in America, Thomas fell ill; despite efforts to fulfill his public obligations, he ended up being taken to a hospital in New York City where he died a few days later; Brinnin’s strange lack of response to the emergency (he didn’t come down to New York from nearby Connecticut until several days later, after the poet had died) stirred up quite a bit of controversy, especially when Thomas’s doctors assigned the cause of death to pneumonia and Brinnin claimed it was alcohol poisoning. The postmortem showed no signs of alcohol being involved in Thomas’s condition, and doctors insisted it had not been an alcoholic coma that Thomas was in but a severe bronchial condition; nevertheless, Brinnin’s assertions played into the myth of the Poet as Self-Destructive Madman, a myth quite popular at the time (and, possibly, still popular now.)

Even more controversy was caused by Brinnin’s publication of the book Dylan Thomas in America, in which he continued to propagate his assertions about the poet’s death and to paint the poet – not completely undeservedly – as a boozer and a womanizer, out of control, in a self-destructive spiral, and functioning without a strong sense of duty to his professional, collegial or marital relationships. Thomas’s family considered Brinnin persona non grata for failing to attend to the poet’s needs while in America and for spreading gossip about him. One reviewer of the biography had this to say about it: “A fascinating read, even if you are not interested in DT. On the surface, a story of wretched excess and inevitable self-destruction, but even in this entirely one-sided account one senses an anxious, self- serving agenda. It was keenly interesting to later read the accounts of Thomas’ family, who regard Brinnin as an exploitative hanger-on who added character assassination to his almost criminal failure to help the dying poet.” Critics have considered the possibility that Brinnin’s indifference and inattention at that crucial time was due to Brinnin being in love with, but rejected by, Thomas. The fact that Brinnin kissed Thomas full on the lips in public on the occasion of one of Thomas’s departures from America might have contributed to that theory.

In spite of the controversy (or perhaps because of it), Dylan Thomas in America sold well, better than Brinnin’s poetry collections had. Brinnin resigned his position at the Poetry Center but continued to spend time with and write about other celebrities in the literary world, many of whom he had met there. He published books about Gertrude Stein, William Carlos Williams, T.S. Eliot, and Truman Capote (a lifelong friend who, according to Brinnin, abandoned his talent and took on “the role of mascot to cafe society.”) Maybe Brinnin submerging himself in the world of other poets meant withdrawing from that world as a poet himself. As he once told an interviewer, ”I think I’m as well known as I deserve to be.”

In any case, he wrote less poetry after the controversy, publishing only one more collection twenty years later, and he focused on cultivating friendships, editing anthologies, and writing biographical pieces and accounts of travel on ocean liners (a passion of his – he crossed the Atlantic Ocean over sixty times.) In some way, his role in Key West was that of the leader of a private literary salon, making sure he was a star in that firmament. His book Sextet is full of gossipy anecdotes about celebrities, including some his own friends or the friends of friends. T.S. Eliot, according to Eliot’s roommate, John Howard, was no slouch when it came to self-regard. Hayward told Brinnin “On the day Time magazine came out with his face on the cover, [Eliot] walked for hours looking for wherever he might find it, shamelessly taking peeks at himself.” Christopher Lehman, who reviewed Sextet for the New York Times, said, “…there’s something about these six easy pieces that makes a reader faintly uneasy in the author’s company – something that makes one feel slightly compromised by having to meet these people under Mr. Brinnin’s auspices.” And Brinnin could be vicious. In a review of one of William Meredith’s books of poetry, Brinnin kills three giants with one stone: “In poetic terms, Meredith takes us into a region recently charted by the knuckleboned asperities of Robert Lowell and by the vaudeville turns of conscience played out in the ‘Dream Songs’ of John Berryman.”

I’ve met enough poets and sat through enough lunches with them to know that their personalities are not always in sync with their poetry — affable and upbeat people can write pessimistic and mean-spirited poems; conversely, whiny and egotistical people can write poems that lift our spirits and fill us with wonder. For me, Brinnin the Gossip comes across at times witty, at other times narcissistic; Brinnin’s poetry, on the other hand, is humble and full of wonder. Without wonder (and its co-conspirator, curiosity) poetry cannot exist, and I agree with Brinnin’s own take on the subject: “Unfortunately, a sense of wonder cannot be instilled, installed, or otherwise attained. Rather it is something like a musical sense — if not quite a matter of absolute pitch, a disposition, something in the genes as exempt from judgment as the incidence of brown eyes or blue.”

The Giant Turtle Grants an Interview

How old are you, Old Silence?

…..I tell time that it is.

And are you full of wonder?

…..Ephemeral verities.

What most do you long for?

…..No end to my retreat.

Have you affections, loves?

…..I savor what I eat.

Do shellbacks talk to shells?

…..Sea is a single word.

Have you some end in mind?

…..No end, and no reward.

Does enterprise command you?

…..I manage a good freight.

Has any counsel touched you?

…..Lie low. Keep quiet. Wait.

Your days – have they a pattern?

…..In the degree of night.

Has solitude a heart?

…..If a circle has a center.

Do creatures covet yours?

…..They knock, but seldom enter.

Have you not once perceived

…..The whole wide world is yours.

I have. Excuse me. I

…..Stay utterly indoors.

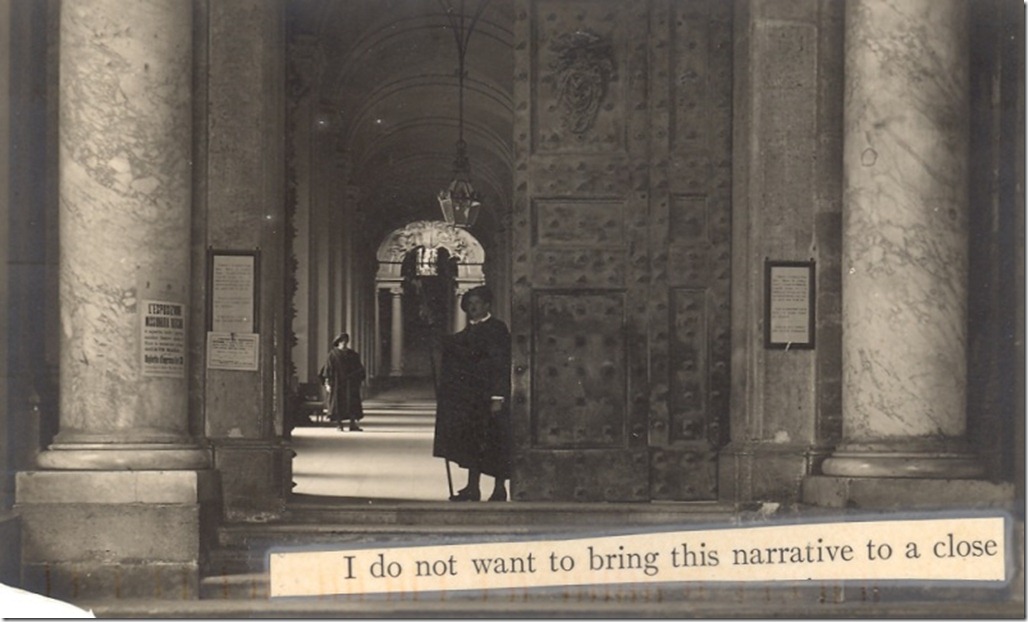

Choosing to put Brinnin’s work in front of the readers of Numéro Cinq, I found myself wondering whether we need to admire an artist — the man himself or the woman herself — whose work we admire. The question was raised pointedly in the movie Amadeus — Mozart as a man is a giggling fool but as a composer is a genius, while Salieri the man is serious and committed to his art while the art he produces is mediocre. Some days I find myself thinking that if a poet is a son of a bitch, a bigot, a boozer, a racist, a loud-mouthed fool, a shameless self-promoter and/or a misogynist in real life, I’d rather not read his work, thank you. Other days, I couldn’t care less who the poet is — I just want to see if the necessary element of wonder is present in the poems; if it is, I can relish them and ignore everything else. My conclusion right now is this: John Malcolm Brinnin may, like Capote, have wasted his talent and become another mascot to café society, but he was wrong about himself — he is not as well-known as he deserves to be. I might not choose to play anagrams or poker under a beach umbrella in Florida with someone like him — by many accounts backbiting, gossipy, and self-aggrandizing . But that has nothing to do with how much I enjoy and admire his poems.

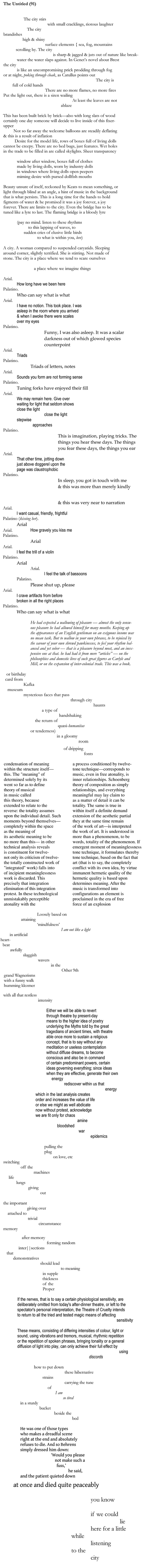

“A Day at the Beach, 1984” – Key West Writers

“A Day at the Beach, 1984” – Key West Writers

From top left: James Merrill, Evan Rhodes, Edward Hower, Alison Lurie, Shel Silverstein, Bill Manville, Joseph Lash, Arnold Sundgaard, John Williams, Richard Wilbur, Jim Boatwright. From bottom left: Susan Nadler, Thomas McGuane, William Wright, John Ciardi, David Kaufelt, Philip Caputo, Philip Burton, John Malcolm Brinnin. Photo by Don Kincaid.

— Julie Larios

Julie Larios is the recipient of an Academy of American Poets Prize and a Pushcart Prize; her work has been published in journals such as The Threepenny Review, Ploughshares, The Atlantic, Ecotone and Field, and has been chosen twice for The Best American Poetry series.

.

.