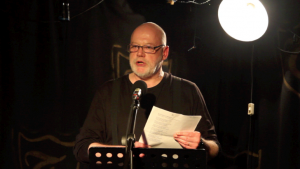

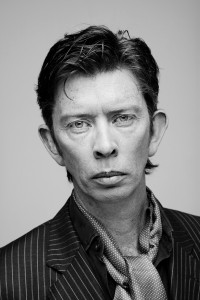

In the same year (1998) John Kelly took the journey from Belfast to Dublin to present the ground-breaking music show Eclectic Ballroom (listen here) on Radio Ireland, this other Irishman was making the journey from Dublin to a remote community in Northern Manitoba (Canada). A few years later when John joined RTÉ, Ireland’s national radio and television broadcaster, to present the award-winning and cult classic Mystery Train, I was still sequestered in my own little world listening to a small First Nations radio station broadcasting local Cree gospel music, Métis fiddle, community announcements, and bingo — so sadly our airwaves never crossed. Since then John has established himself as one of Ireland’s best known music and arts broadcasters currently hosting The Works, an arts series on RTÉ Television, and The John Kelly Ensemble on RTÉ lyric FM. But as if this wasn’t enough, he has also published a number of critically acclaimed novels. The extract below is from his forthcoming novel, From Out of the City (Dalkey Archive Press). The language is rich, exuberant. At times like “that terrifying colony ensconced in the ruins of Liberty Hall,” it dive-bombs, screeches, wheels, and plummets; other times it flourishes in a lush lyrical reverie. And funny, shrewdly funny. Joyce, Beckett, Donleavy….quietly wandering around in the background, amidst the ruins, smiling wistfully at the outrageous absurdity of it all.

— Gerard Beirne

Dublin, some years from now, and the President of the United States has just been assassinated during a state dinner in his honour. The official account has already taken hold but a hawk-eyed octogenarian named Monk, believing that there’s nothing that cannot be known, has a version of his own—a dark and twisted tale of both the watcher and the watched.

But this, says Monk, is no thriller or invented tale of suspense. It is, he insists, an honest and faithful record of breakage and distress at a time when dysfunction—personal, local, national, global and even cosmic—pervades all. A time when everything is already broken and when, in many ways, the shooting of a pill-popping President is neither here nor there. The only thing that matters, Monk tells us, is the truth. And this is why, stationed high in his attic room with a Stoli in a highball, he does what he does. “There’s divinity in it,” he says. “And a modicum of love.”

“The book begins with a prologue in which the narrator, Monk, tells us of the assassination of the American President while on a state visit to Ireland and gives his thoughts on same. Here, with Chapter One, Monk tells us about himself and his place and he begins to speak of his very particular activities and preoccupations.”

— John Kelly

The feast of St. Isidore of Seville and I awoke to the sound of rain. It panicked me briefly – that old spurt of fear that I’d been transported through the night to some foreign land where summer downpours are still imaginable. I thought perhaps that I was in Iceland or Nova Scotia but a quick scan across the yellowing sweep of my pillow was enough to assure me that my locus was as was – my own country, my own house, my own room, my own scratcher. Which was very good news. And what’s more, there had been no bad dreams, it seemed, from which to thrash awake. No twistings of the limbs, no tightenings in the chest, no pulses in the lumpy bald- ness of my head. An erection too no less. On this unexpectedly wet morning of my eighty-fourth birthday, lo and behold, a boner of pure marble. Happy Birthday to me, I whispered to myself. For I’m not a squishy marshmallow. We’ll roast you on a stick. Bum-tish!

Eight tumbling decades since I first landed at the South Dublin Lying-in Hospital, Holles Street named for Denzille Holles, Earl of Clare – a place now infested with cut-throats, brigands, smackheads and rats but still serving then, at the hour of my arrival, as The National Maternity. A very palace of human nature.

— What kind of a name is Monk? asks the midwife.

— Named for Thelonious, says my father, his eye on the clock.

— Felonious?

— θ, says my father, Thelonious with a θ.

— Oh right, says the midwife (a culchie). Little Thelonious.

— Yes, says my father, as in Thelonious Sphere.

— You have me there again, says the midwife (Roscommon).

— Thelonious fucking Monk, says my mother with a sigh. A fucking trumpet player.

— Piano, says my father, buttoning up his coat. And celeste on Pannonica.

— I see, says the midwife, not seeing at all (Boyle).

— At one stage, says my mother, this prick was pushing for Stockhausen.

— Stock what? says the midwife (somewhere out beyond Boyle).

— And Suk, says my mother. That was another one.

— It’s pronounced Sook, says my father, and I never once suggested Suk.

— Stockhausen, says my mother. For fucksake. Stockhausen or Suk.

And so this is the pair — Bleach and Ammonia — who gave me life and this grand ruin of a house in which to enjoy it. 26 Hibernia Road, Dún Laoghaire. Three-storey, over-basement, Victorian residence c.1850, features including original replaces, quality cornice-work, centre roses, paneled doors and five generous bedrooms of proportions considered gracious. From the street, it resembles every other house in this section save for its evident security apparatus — a multitude of surveillance cameras perched like blackened gargoyles on the walls. All of it necessary alas as we live in changed times and while Hibernia Road, leading to Britannia Avenue, now Casement Avenue and named for Sir Roger, was once an address considered salubrious (c.1850), it’s now no more than a desolate trench of dereliction and crime. Burned-out, sea-blown, not altogether inhabited and shoved well back from the main strip, Hibernia Road is, these days, neither visited nor traveled. Not by citizens. Not by Guards. Not even by the gentlemen and ladies of the military. Ours or theirs.

In fact the whole town of Dún Laoghaire, named for a 5th-century king of Tara, is now largely defunct and undesirable. Like a mouthful of rotten teeth it grins ever more grotesquely into the swill of Dublin Bay — Cuan Bháile Átha Cliath — polluted beyond all salvage by plutonium, uranium and flesh and where sits, in apparent permanence, a Brobdingnagian aircraft carrier, named not for Kevin Barry, just a lad of eighteen summers, or Maggie Barry who sang “The Flower of Sweet Strabane”, or James J. Barry of Barry’s Original Blend Corkonian Tea, but for Commodore John Barry, the Father of the American Navy, born in Wexford in 1745. The thing has been sitting there for so long now that people don’t even see it any more. And if they do they pass no further remarks. And in any case, don’t all the nice girls love a sailor?

Dún fucking Laoghaire. Where I have lived all my life. Dún Laoghaire, Dún Laoire, Dunleary (briefly Kingstown) where the monks of St. Mary’s caught their shoals of herring. In the 17th century it was a landing place for big-shots and men-of-war and in 1751 a shark was hauled ashore. In 1783 an African diver disappeared under the waves in a diving bell, and in 1817 the first stone of the East Pier was laid and all those virgin tonnes of granite were dug out of Dalkey Hill and dumped. Otherwise there’s not much to commend the place at all. Not now anyway. Dún Laoghaire. 9.65 km ESE of the metropolitan hub — the very spot where the Millennium Spire used to be and, before that again, an effigy in Portland Stone of Lord Horatio Nelson, Viscount and Baron Nelson of the Nile and of Burnham Thorpe etc., etc. e Pillar blown to smithereens of granite and black limestone in 1966. Granite from Kilbride. Pedestal, column and capital. His nibs on the summit, myopic, head lathered in the guano of herring gulls. Vice Admiral of the White and my two uncles that did it. Maguire and Patterson. And Clery’s Clock stopped dead at 1:31. Faoileán scadán. The colony. The colonized. Nelson’s blasted colon : the colonoscopy for fucksake. And I’m sleepy now. Might roll over yet and perhaps some dreams will come. And snooze. And slumber. And I might as well. Only young once. Snuggle and snooze.

But of course this rain was wrong and I raised my head to check once more that this really was my room. And surely it must be. The goose-down duvet, grey and unstained, the clock and the Glock, the empty glass still fragrant with dusty Hennessy, the ancient maps of Paris and the Dingle Peninsula, the curling snaps of smiling people long dead, and the sideboard with the stolen bust of Berkeley fitted with old wraparound shades, now a bookend for the little concertina of Sci-Fi paperbacks all read so eagerly when I was a boy so happily in love with the future. Berkeley, Bishop of Cloyne, nicked sixty years ago from the Long Room of Trinity College and taken out the front gate in a wheelbarrow. So yes, I assured myself once more, with an element of certainty now, that this was, surely to goodness, my room. My own leaba in number 26 and I had not, unless I was grievously mistaken, been kidnapped or otherwise rendered in my sleep. And it was my birthday too. And in Dún Laoghaire, as if to mark the occasion, there appeared to be actual precipitation.

These thoughts, such as they were, uncontrolled, semi-conscious and leapfrogging each other, were suddenly interrupted by a most extravagant yawn. My jaws shifted and cracked and a pain shot through my skull like a little private bullet of my own. And then there followed the long slow-motion masticatory shimmy in order to correct the jawbones again and with that second crack there came a certain peace, not so much a click this time as a clock, and I could relax again, still alive, glubbing now on my pillow like an old lippy cod. Gadus morhua. Extinct source of vitamins A, D, E and several essential fatty acids. And what a treat that would be on my birthday. Cod and Chips from Burdock’s of Werburgh Street, named for the church of St. Werburgh, named for Werburgh of Chester, a Benedictine abbess, prophetess and seer of the secrets of hearts. And Burdock’s had haddock and ray and lemon sole and scampi and goujons — until that final scare, that is, and everyone stopped eating fish. Even the cormorants in Dún Laoghaire stopped eating fish and they all died away with the seals. The Germans call it Seezunge. And the Spaniards too. I do miss a bit of tongue, says Missus McClung. Lenguado. All things lingual and gustatory. Larus argentatus. And that terrifying colony ensconced in the ruins of Liberty Hall, dive-bombing all who might chance it on foot across the Tara Street Bridge. Screeching. Wheeling. Plummeting. And the best of it all is that it’s more than likely that I know every last one of them — both chancer and gull — by name, reputation and record. Because nothing gets past a man as invisible as me. Oh where oh where is that gallant man? Eighty-four today.

But now on this unexpectedly wet morning in my gargoyled house on Hibernia Road, my sub-duvet reverie at an end, I finally manoeuvred myself to the edge of the bed, gripped my thighs and pressed down hard, the pressure of it translating to push and the body yielding to forces and physics and, whatever the kinetics, whatever the systems and sequences of internal pulleys and cranks called upon so early in the day, my creaking self slowly loomed and my cool morning arse presented itself to the blue grain of the room. I’m up, says I. Another day another dolor — and I announced in the darkest voice of MacLiammóir, Comedia nita est. Then chuckling like a changeling in my white t-shirt and abby boxers I lurched to the window, parted the curtains and peered into the light. Time to think straight now. Time to assess. Time to focus. To get, says you, to the point.

But again I stress that this is not about Richard King or his assassination. Nor is it about how, when they asked me where I was when it happened, the incident in question, that I was able to tell them that I was at home, at number 26, seated on my sofa, a Stoli in a highball, watching the rolling coverage just like everybody else. Or about the fact (and this is something I, of course, neglected to tell them) that I could barely breathe that night as I waited, waited, waited for that newsflash to come, for confirmation from the Castle that the bullet had flown and that ambition’s debt had finally been paid. No. Not at all. This is not about any of that. And it never once was. It’s more about me and where I live and what I do. And it’s also about those people in my care and who will enter soon. But for now this is just me, on my birthday, eighty-fourth, out of bed and at my bedroom window in my boxers and my vest.

And so what did I see? One of my foxes, soaked and muddy, was dragging a blue hula hoop across what used to be a flowerbed and I immediately pictured what I must have missed — the moonlit fox gyrating like a pole dancer and counting out the revolutions. The thought of it made me giggle and I decided that perhaps this really was a very good day in Dún Laoghaire. There hadn’t been rain in months and now here it was at last. Real dancing rain just like the glorious downpours of my childhood and I could smell within it some strange hint of the perpetual. Pandiculation followed. A temporary deafness. Then elbow pain and recovery. I placed my pistol in the drawer, closed it tight and then, and only then, I began to pad the bare boards to the bathroom. I take no chances now, ever since the time I found myself half asleep at the sink, putting toothpaste on the barrel, about to scrub my thirty-two teeth with a loaded weapon. I’m far from doddery but even so.

The electric is erratic these days, water even more so, and so I showered for the thirty-second legal max. en I dried myself off, dressed quickly in a clean white t-shirt, shorts and sloggy bottoms and descended to make myself a camomile tea with honey substitute. Lots of men my age couldn’t manage these stairs at all but I’m as supple as I ever was, my joints constantly swimming in fake fish oil. Thanks to the good folks in Nippon my bones are fortified by every available mineral, vitamin, and dietary silicon smoothie, and once I’m up and about I have neither ache nor pain. Not physical pain at any rate. Jesus, Mary and Joseph where would we be without the synthetics? And without the Japanese? Dab hands the Japs and we’d be lost entirely without them. But fuck it I do miss the bees. I wish the Japanese would sort the bees. And the bee’s knees. For honey, substitute is no substitute. The signs were there for years and nobody lifted a fucking finger. It wouldn’t have happened in Japan. Only it did. World without bees. Amen.

From the kitchen window I watched the fox, still tossing the hoop, and although I always hate to spook such a scene, the instant I punched in the code, Vulpes vulpes shot off like a brushstroke and the hula hoop rolled, keeled and settled on the burning grass like a portal. Sorry Foxy Loxy, I muttered as I put on my trainers and stepped out into the air, raising my face briefly to the skies for the wet of the rain, the actual rain, and I walked briskly, swerving around my dripping barricade of dumped antiques, down to the tumbledown shed which, these days, leans drunkenly against the sycamore. I took my tea with me. The rain was warm and syrupy and it plashed with pleasure in the steaming mug.

There was a wood pigeon balled up in a beech (I have the eyes of a raptor) and a blue-tit was hanging on the giant echium — the self-seeding, tit-feeding echium growing about a foot a day like some slow-motion purple rework. There were wrens up until about fifteen years ago. Troglodytes troglodytes. And blackbirds too. And I used to see them run low across the lawn like infantry out of their trenches and I loved to listen to them sing, watching them snuggled in the holly bush, thinking themselves well defended in the jags.

These new alien finches can be unexpected company at times, but it’s not the same. And the shrikes I can do without. Butcher birds. Cruel impalers. Cracticus something and there’s always one on the shed, eyeing me up, a shrew in its bill, or some supersized beetle which arrived in a suitcase from West Africa.

The shed (the dacha I call it) is warped and narrow and it houses century old, half-empty buckets of paint, an original mountain bike, an axe, bits of obsolete surveillance equipment and sheetweb spiders the size of kittens. I love it in there. Most especially in the rain. As a child, the sound of rain always soothed me and I used to hunker in this very same shed, watching the showers lash the cordylines in scenes which seemed tropical. For a moment, I felt like I was the same child again, sheltered in my hidey hole, enjoying the thrilling little shivers which enveloped me — Bleach and Ammonia back in the house arguing about the nap of the lawn or the pressure in the tap. Heavenly, I told myself, perfectly at peace and in the shed, and then with an almost overwhelming sense of liberation, I lowered the front of my sloggy bottoms and pissed with panache from the dacha porch. Breathing deeply like some ancient God I targeted the agapanthus with my jet.

On my first day as sole owner and occupier of number 26 Hibernia Road, flush with freedom and possession, the very first thing I did was relieve myself in this very garden. As the Gods made Orion. The second thing I did, and just as symbolic, was remove most of the contents and dump them outside. Bedsteads, mattresses, tables, chairs, sideboards, china cabinets, Ottomans, bedside lockers, standard lamps, carpets, rugs, mats, holy statues, vases and assorted prints by late 20th-century racketeers. These I piled on the flower- beds before going back inside to lie on cushions on the floor and crank up the thumping Hi-Fi. Compact discs in those days. My preference then was for bands like New Order, Pere Ubu, Suicide, and The Fall. My father’s study, with its CDs of Bartók, Stravinsky and Stockhausen, I locked up and left alone. He was a vulpine man, my father. Vulpecular. But he liked his music, eschewing the wigs for the moderns and enjoying it in his own way. I liked it well enough too, but I was never in the mood for it. Not in those days anyway.

By four in the morning, I had begun to realize my actual discomfort and I returned to the barricade to strip it of essentials – one sofa, one rug, one kitchen table and one chair. These I reinstated in the house while everything else was left bewildered to the elements, where it lies to this day, piled up and creaking, providing shelter and security for generations of scraggy Dún Laoghaire foxes, all of them, including the one with the hula hoop, born and bred within its labyrinthine heap. Otherwise the place hasn’t been touched at all and number 26 has somehow distilled with natural precision to the point of being quite perfect for my purposes.

On two floors, front and back, the rooms full of boxes (cereal and shoe) stuffed with photographs, files, scribbles, cuttings and notes, now packed almost to the ceiling, decades of profiling stacked in dense little cities of leaning piles of paper and card. Priceless material all of it, of course, and a fire hazard beyond all imagining, but if it goes up, it goes up. It’s no use without me anyway. Without meaning. Like a web without a spider.

At the very top of the house, with a dormer window facing the street, is the actual HQ. On one side of the room, under the plunging slope of the ceiling, is a bank of monitors, permanently on, which links me to the city and beyond. The rest of the space is commanded by a high-back swivel chair of distressed black leather and a fold-out single bed covered in notebooks, orange peel, pencils and sharpenings — the never forgotten stench of desk — all laid out on a carpet so grey and so stained with decades of spilled coffee as to resemble, with some accuracy, a map of the surface of the moon. And this is where I do what I do. And I do it without cease. It takes sustained and careful husbandry but I’m able for it still. There’s divinity in it. And a modicum of love.

— John Kelly

John Kelly has published several works of fiction including, Grace Notes & Bad Thoughts and The Little Hammer. His short stories have appeared in various publications and a radio play called The Pipes (listen here) was broadcast in 2013. He lives in Dublin, Ireland, where he works in music and arts broadcasting.

Gerard Beirne is an Irish author who moved to Canada in 1998. He is a past recipient of The Sunday Tribune/Hennessy New Irish Writer of the Year award. He was appointed Writer-in-Residence at the University of New Brunswick 2008-2009 and continues to live in Fredericton where he is a Fiction Editor with The Fiddlehead. He has published three novels, including The Eskimo in the Net (Marion Boyars Publishers, London, 2003) which was shortlisted for the Kerry Group Irish Fiction Award 2004 for the best book of Irish fiction and was selected as Book of the Year 2004 by The Daily Express (England). His most recent novel is Charlie Tallulah (Oberon Press). His poetry collections include Digging My Own Grave (Dedalus Press) which was runner-up in The Patrick Kavanagh Award. His personal website is here.

Nephin mountain

Nephin mountain  Amanda Bell and daughter near the summit of Mount Nephin

Amanda Bell and daughter near the summit of Mount Nephin Author 1971 or 1972

Author 1971 or 1972  The author at Pontoon, 1972

The author at Pontoon, 1972 Author’s grandfather and brother collecting turf

Author’s grandfather and brother collecting turf The author and her brother

The author and her brother Mayo Road

Mayo Road